Snakefly

| Snakefly Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| FemaleDichrostigma flavipes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Clade: | Neuropterida |

| Order: | Raphidioptera Handlirsch,1908 |

| Suborders | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Snakefliesare a group ofpredatoryinsectscomprising theorderRaphidiopterawith two extant families:RaphidiidaeandInocelliidae,consisting of roughly 260species.In the past, the group had a much wider distribution than it does now; snakeflies are found intemperate regionsworldwide but are absent from thetropicsand theSouthern Hemisphere.Recognisable representatives of the group first appeared during the EarlyJurassic.They are arelictgroup, having reached their apex of diversity during theCretaceousbefore undergoing substantial decline.

An adult snakefly resembles a lacewing in appearance but has a notably elongatedthoraxwhich, together with the mobile head, gives the group their common name. The body is long and slender and the two pairs of long, membranous wings are prominently veined. Females have a large and sturdyovipositorwhich is used to deposit eggs in some concealed location. They areholometabolousinsects with a four-stagelife cycleconsisting of eggs,larvae,pupaeand adults. In most species, the larvae develop under the bark of trees. They may take several years before they undergometamorphosis,requiring a period of chilling before pupation takes place. Both adults and larvae are predators of soft-bodiedarthropods.

Description[edit]

Adult snakeflies are easily distinguished from similar insects by having an elongatedprothoraxbut not the modifiedforelegsof themantis-flies.Most species are between 15 and 30 mm (0.6 and 1.2 in) in length. The head is long and flattened, and heavilysclerotised;it may be broad or taper at the back, but is very mobile. The mouthparts are strong and relatively unspecialised, being modified for biting. The largecompound eyesare at the sides of the head. Members of the familyInocelliidaehave nosimple eyes;members of theRaphidiidaedo have such eyes, but are mostly differentiated by elimination, lacking the traits found in inocelliids. The prothorax is notably elongated and mobile, giving the group its common name of snakefly. The three pairs of legs are similar in size and appearance. The two pair of dragonfly-like wings are similar in size, with a primitive venation pattern, a thickened leading edge, and a coloured wingspot, thepterostigma.Inocelliids lack a cross vein in the pterostigma that is present in raphidiids. The females in both families typically have a longovipositor,which they use to deposit their eggs into crevices or under bark.[1][2][3][4]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Snakeflies are usually found in temperateconiferous forest.They are distributed widely around the globe, the majority of species occurring in Europe and Asia, but also being found in certain regions of Africa, western North America and Central America. In Africa, they are only found in the mountains north of theSahara Desert.In North America, they are found west of theRocky Mountains,and range from southwest Canada all the way to the Mexican-Guatemalan Border, which is the furthest south they have been found in the western hemisphere. In the eastern hemisphere, they can be found from Spain to Japan. Many species are found throughout Europe and Asia with the southern edge of their range in northern Thailand and northern India.[5]Snakeflies have arelictdistribution, having had a more widespread range and being more diverse in the past; there are more species in Central Asia than anywhere else.[3]In the southern parts of their range, they are largely restricted to higher altitudes, up to around 3,000 m (10,000 ft).[4]Even though this insect order is widely distributed, the range of individual species is often very limited and some species are confined to a single mountain range.[6]

Life cycle[edit]

Snakeflies areholometabolousinsects, having a four-stage life cycle with eggs, larvae, pupae and adults. Before mating, the adults engage in an elaborate courtship ritual, including a grooming behaviour involving legs and antennae. In raphidiids, mating takes place in a "dragging position", while in inocelliids, the male adopts a tandem position under the female; copulation may last for up to three hours in some inoceliid species. The eggs are oviposited into suitable locations and hatch in from a few days to about three weeks.[4]

The larvae have large heads with projectingmandibles.The head and the first segment of the thorax are sclerotised, but the rest of the body is soft and fleshy. They have three pairs of true legs, but noprolegs.However, they do possess an adhesive organ on the abdomen, which they can use to fasten themselves to vertical surfaces.[1]

There is no set number ofinstarsthe larvae will go through, some species can have as many as ten or eleven. The larval stage usually lasts for two to three years, but in some species can extend for six years.[5]The final larval instar, the prepupal stage, creates a cell in which the insectpupates.The pupa is able to bite when disturbed, and shortly before the adult emerges, it gains the ability to walk and often leaves its cell for another location.[7]All snakeflies require a period of cool temperatures (probably around 0 °C (32 °F)) to induce pupation.[5]The length of the pupation stage is variable. Most species pupate in the spring or early summer, and take a few days to three weeks beforeecdysis.If the larvae begin pupation in the late summer or early fall, they can take up to ten months before the adults emerge.[5]Insects reared at constant temperatures in a laboratory may become "prothetelous", developing the compound eyes and wingpads of pupae, but living for years without completingmetamorphosis.[4]

Ecology[edit]

Adult snakeflies are territorial and carnivorous organisms. They are diurnal and are importantpredatorsofaphidsandmites.Pollen has also been found in the guts of these organisms and it is unclear whether they require pollen for part of their lifecycle or if it is a favoured food source.[5][4]The larvae of many raphidiids live immediately below the bark of trees, although others live around the tree bole, in crevices in rocks, amongleaf litterand indetritus.Here they feed on the eggs and larvae of other arthropods such as mites,springtails,spiders,barklice,sternorrhynchidsandauchenorrhynchids.[3]The actual diets of the larvae vary according to their habitats, but both larvae and adults are efficient predators.[4]

Predators of snakeflies include birds; in Europe, these are woodland species such as thetreecreeper,great spotted woodpecker,wood warbler,nuthatch,anddunnock,as well asgeneralistinsect-eating species such as thecollared flycatcher.[8]Typically 5-15% of snakefly larvae are parasitized, mainly byparasitoid wasps,but rates as high as 50% have been observed in some species.[5]

Evolution[edit]

During theMesozoicera (252 to 66 mya), there was a large and diverse fauna of Raphidioptera as exemplified by the abundant fossils that have been found in all parts of the world. This came to an abrupt end at the end of theCretaceousperiod, likely as a result of theCretaceous–Paleogene extinction event(66 mya) when an enormousasteroidis thought to have hit the Earth. This seems to have extinguished all but the most cold-tolerant species of snakefly, resulting in the extinction of the majority of families, including all the tropical and sub-tropical species. The two families of present-day Raphidioptera are thus relict populations of this previously widespread group.[4]They have been consideredliving fossils,because modern-day species closely resemble species from the earlyJurassicperiod (140 mya).[6]There are about 260extantspecies.[5]

Fossil history[edit]

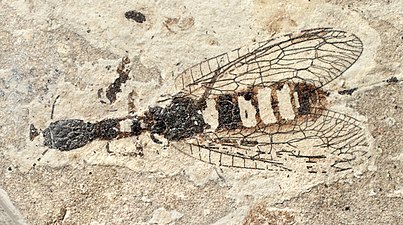

Severalextinctfamilies are known only fromfossilsdating from theLower Jurassicto theMiocene,[9]the great majority of them belonging to thesuborderRaphidiomorpha.[9]ThetransitionalMiddle JurassicJuroraphidiidaeform a clade with the Raphidiomorpha.[10]

Phylogeny[edit]

Molecular analysis usingmitochondrialRNA and the mitogenome has clarified the group's phylogeny within theNeuropterida,as shown in thecladogram.[11][12]

| Neuropterida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name Raphidioptera is formed from Greek ῥαφίς (raphis), meaning needle, and πτερόν (pteron), meaning wing.[13]

TheMegaloptera,Neuroptera(in the modern sense) and Raphidioptera are very closely related, forming the groupNeuropterida.[14]This is either placed atsuperorderrank, with theHolometabola– of which they are part – becoming an unrankedcladeabove it, or the Holometabola are maintained as a superorder, with an unranked Neuropterida being a part of them. Within the holometabolans, the closest living relatives of Neuropterida are thebeetles.[15]

Two suborders of Raphidioptera and their families are grouped below according toEngel(2002) with updates according to Bechly and Wolf-Schwenninger (2011) and Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuenteet al.(2012). For lists of genera, see the articles on the individual families.[9][16][17] Raphidioptera

- †Prisca Enigma tomorphaEngel,2002

- ?GenusChrysoraphidiaLiuet al.,2013-Yixian Formation,China Early Cretaceous (Aptian) (some authors have suggested closer affinities to Neuroptera[18])

- Family †Prisca Enigma tidaeEngel, 2002- (Early Jurassic-Early Cretaceous)

- Genus †HondelagiaBode,1953-Green Series,Germany, Early Jurassic (Toarcian)

- Genus †Prisca EnigmaWhalley,1985-Charmouth Mudstone Formation,United Kingdom, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)

- Genus †SukacheviaKhramov, 2020-Karabastau Formation,Kazakhstan, Late Jurassic

- Genus †CretohondelagiaKhramov, 2020- Khasturty locality, Russia, Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Family †JuroraphidiidaeLiu, Ren, & Yang, 2014

- Genus †JuroraphidiaLiu, Ren, & Yang, 2014-Jiulongshan Formation,China, Middle Jurassic

- RaphidiomorphaEngel, 2002

- Family †MetaraphidiidaeBechly & Wolf-Schwenninger, 2011- (Early Jurassic)

- Genus †MetaraphidiaWhalley, 1985- Charmouth Mudstone Formation, United Kingdom, Early Jurassic (Sinemurian)Posidonia Shale,Early Jurassic (Toarcian)

- Family †BaissopteridaeMartynova,1961- (Cretaceous-Eocene)

- Genus †AllobaissopteraLu, Zhang, Wang, Engel, & Liu, 2020-Burmese amber,Mid Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian)

- Genus †AscalaphariaNovokshonov, 1990- Kzyl-Zhar, Kazakhstan, Late Cretaceous (Turonian)

- Genus †AustroraphidiaWillmann, 1994-Crato Formation,Brazil, Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Genus †BaissopteraMartynova, 1961- Crato Formation, Brazil, Yixian Formation, China,Zaza Formation,Russia Early Cretaceous (Aptian),Spanish amber,Early Cretaceous (Albian) Burmese amber

- Genus †BurmobiassopteraLu, Zhang, Wang, Engel, & Liu, 2020- Burmese amber, Mid Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian)

- Genus †CretoraphidiaPonomarenko, 1993- Zaza Formation, Russia Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Genus †CretoraphidiopsisEngel, 2002-Dzun-Bain Formation,Mongolia, Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Genus †DictyoraphidiaHandlirsch, 1910-Florissant Formation,Colorado, United States, Eocene (Priabonian)

- Genus †ElectrobaissopteraLu, Zhang, Wang, Engel, & Liu, 2020- Burmese amber, Mid Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian)

- Genus †LugalaWillmann, 1994- Dzun-Bain Formation, Mongolia, Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Genus †MicrobaissopteraLyuet al.,2017- Yixian Formation, China, Early Cretaceous (Aptian)

- Genus †RhynchobaissopteraLu, Zhang, Wang, Engel, & Liu, 2020- Burmese amber, Mid Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian)

- Genus †StenobaissopteraLu, Zhang, Wang, Engel, & Liu, 2020- Burmese amber, Mid Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian)

- Family †MesoraphidiidaeMartynov, 1925(Paraphyletic[19][20]) (30+ genera) - (Middle Jurassic-Late Cretaceous)

- NeoraphidiopteraEngel, 2007- (Paleogene-Recent)

- FamilyInocelliidaeNavás

- Subfamily †ElectrinocelliinaeEngel, 1995

- SubfamilyInocelliinaeNavás

- FamilyRaphidiidaeLatreille,1810

- FamilyInocelliidaeNavás

- Family †MetaraphidiidaeBechly & Wolf-Schwenninger, 2011- (Early Jurassic)

- Incertae sedis

- Genus †ArariperaphidiaMartins-Neto&Vulcano,1989- (Lower Cretaceous; Brazil)

Possible biological pest control agents[edit]

Snakeflies have been considered a viable option forbiological controlofagriculturalpests. The main advantage is that they have few predators, and both adults and larvae are predacious. A disadvantage is that snakeflies have a long larval period, so their numbers increase only slowly, and it could take a long time to rid crops of pests; another issue is that they prey on a limited range of pest species.[6]An unidentified North American species was introduced into Australia and New Zealand in the early twentieth century for this purpose, but failed to become established.[4]

References[edit]

- ^abHoell, H. V.; Doyen, J. T.; Purcell, A. H. (1998).Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity(2nd ed.).Oxford University Press.pp. 445–446.ISBN0-19-510033-6.

- ^Gillot, C. (1995)."Raphiodioptera".Entomology(2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 293–295.ISBN978-0-306-44967-3.

- ^abcGrimaldi, David;Engel, Michael S.(2005).Evolution of the Insects.Cambridge University Press.pp. 336–339.ISBN978-0-521-82149-0.

- ^abcdefghResh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (2009).Encyclopedia of Insects.Academic Press.pp. 864–865.ISBN978-0-08-092090-0.

- ^abcdefgAspöck, Horst (2002)."The Biology of Raphidioptera: A Review of Present Knowledge"(PDF).Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.48(Supplement 2): 35–50.

- ^abcHarring, E.; Aspöck, Horst (2002). "Molecular phylogeny of the Raphidiidae".Systematic Entomology.36:16–30.doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2010.00542.x.S2CID84998818.

- ^Kovarik, P. et al. (1991) Development and behavior of a snakefly,Raphidia bicolorAlbada (Neuroptera: Raphidiidae)

- ^Szentkiralyi, F.; Kristin, A. (2002). "Lacewings and Snakeflies as Prey for Bird Nestlings in Slovakian Forest Habitats".Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.48.

- ^abcEngel, M. S. (2002)."The Smallest Snakefly (Raphidioptera: Mesoraphidiidae): A New Species in Cretaceous Amber from Myanmar, with a Catalog of Fossil Snakeflies"(PDF).American Museum Novitates(3363): 1–22.doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)363<0001:TSSRMA>2.0.CO;2.hdl:2246/2852.S2CID83616111.

- ^abLiu, Xingyue; Ren, Dong; Yang, Ding (2014)."New transitional fossil snakeflies from China illuminate the early evolution of Raphidioptera".BMC Evolutionary Biology.14(1): 84.doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-84.ISSN1471-2148.PMC4021051.PMID24742030.

- ^Yue, Bi-Song; Song, Nan; Lin, Aili; Zhao, Xincheng (2018)."Insight into higher-level phylogeny of Neuropterida: Evidence from secondary structures of mitochondrial rRNA genes and mitogenomic data".PLOS ONE.13(1): e0191826.Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1391826S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191826.ISSN1932-6203.PMC5790268.PMID29381758.

- ^Yan, Y.; Wang Y; Liu, X.; Winterton, S. L.; Yang, D. (2014)."The First Mitochondrial Genomes of Antlion (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) and Split-footed Lacewing (Neuroptera: Nymphidae), with Phylogenetic Implications of Myrmeleontiformia".International Journal of Biological Sciences.10(8): 895–908.doi:10.7150/ijbs.9454.PMC4147223.PMID25170303.

- ^Agassiz, Louis;Corti, Elio."Nomenclator zoologicus".Summa Gallicana.Retrieved13 September2019.

- ^Oswald, John D.; Machado, Renato J. P. (2018). "21: Biodiversity of the Neuropterida (Insecta: Neuroptera, Megaloptera, and Raphidioptera)". In Foottit Robert G.; Adler, Peter H. (eds.).Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, II.John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp. 627–672.doi:10.1002/9781118945582.ch21.ISBN9781118945582.

- ^Beutel, Rolf G.; Pohl, Hans (2006)."Endopterygote systematics – where do we stand and what is the goal (Hexapoda, Arthropoda)?".Systematic Entomology.31(2): 202–219.doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2006.00341.x.S2CID83714402.

- ^Pérez-de la Fuente, R.; Peñalver, E.; Delclòs, X.; Engel, M.S. (2012)."Snakefly diversity in Early Cretaceous amber from Spain (Neuropterida, Raphidioptera)".ZooKeys(204): 1–40.doi:10.3897/zookeys.204.2740.PMC3391719.PMID22787417.

- ^Bechly, G.; Wolf-Schwenninger, K. (2011)."A new fossil genus and species of snakefly (Raphidioptera: Mesoraphidiidae) from Lower Cretaceous Lebanese amber, with a discussion of snakefly phylogeny and fossil history"(PDF).Insect Systematics and Evolution.42(2): 221–236.doi:10.1163/187631211X568164.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 March 2014.

- ^Khramov, Alexander V. (3 October 2021)."The youngest record of Prisca Enigma tidae (Insecta: Neuropterida) from the Mesozoic of Kazakhstan and Russia".Historical Biology.33(10): 2432–2437.doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1800683.ISSN0891-2963.S2CID225501089.

- ^Perkovsky, Evgeny E.; Makarkin, Vladimir N. (2019). "A new species ofSuccinoraphidiaAspöck & Aspöck, 2004 (Raphidioptera: Raphidiidae) from the late Eocene Rovno amber, with venation characteristics of the genus ".Zootaxa.4576(3): 570–580.doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4576.3.9.PMID31715754.S2CID132831006.

- ^Makarkin, Vladimir N.; Archibald, S. Bruce; Jepson, James E. (2019). "The oldest Inocelliidae (Raphidioptera) from the Eocene of western North America".The Canadian Entomologist.151(4): 521–530.doi:10.4039/tce.2019.26.S2CID196660529.

Further reading[edit]

- Aspöck, H. (2002)The biology of Raphidioptera: A review of present knowledge.Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae48(Supplement 2): 35–50.

- Carpenter, F. M. (1936) Revision of the Nearctic Raphidiodea (Recent and Fossil).Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences71(2): 89–157.

- Grimaldi, David;Engel, Michael S.(2005)Evolution of the Insects.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-82149-5

- Maddison, David R. (1995)Tree of Life Web Project–Raphidioptera. Snakeflies.

External links[edit]

- Oswald, John D. (2023).Neuropterida Species of the World. Lacewing Digital Library, Research Publication No. 1.(an online catalog that includes data on the Raphidioptera species of the world)

- Oswald, John D. (2023).Bibliography of the Neuropterida. Lacewing Digital Library, Research Publication No. 2.(an online bibliography that includes data on the global scientific literature of the order Raphidioptera )

- Lacewing Digital Library(a web portal that provides access to a suite of online resources that contain data on the order Raphidioptera )

![Juroraphidia longicollum (†Juroraphidiidae) transitional fossil of Middle Jurassic age, from China[10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a0/Juroraphidia_longicollum.jpg/292px-Juroraphidia_longicollum.jpg)