Reading Abbey

It has been suggested thatAbbey Mill, Readingbemergedinto this article. (Discuss)Proposed since May 2024. |

Thechapter house,from the site of the monks' dormitory | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The Abbey of Reading, dedicated to the Virgin and St John the Evangelist |

| Order | Cluniac |

| Established | 18 June 1121 |

| Disestablished | 1539 |

| Dedicated to | Mary, mother of Jesus John the Evangelist |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Henry I of England |

| Important associated figures | Hugh Faringdon |

| Site | |

| Location | Reading, Berkshire,England |

| Coordinates | 51°27′22.85″N0°57′54.31″W/ 51.4563472°N 0.9650861°W |

| Visible remains | Inner rubble cores of the walls of the major buildings; gateway and hospitium intact. |

| Public access | Open daily |

Reading Abbeyis a large,ruinedabbeyin the centre of the town ofReading,in the English county ofBerkshire.It was founded byHenry Iin 1121 "for the salvation of my soul, and the souls ofKing William, my father,and ofKing William, my brother,andQueen Maud, my wife,and all my ancestors and successors. "In its heyday the abbey was one of Europe's largest royalmonasteries.[1]The traditions of the Abbey are continued today by the neighbouringSt James's Church,which is partly built using stones of the Abbey ruins.[2][3]

Reading Abbey was the focus of a major £3 million project called "Reading Abbey Revealed" which conserved the ruins and Abbey Gateway and resulted in them being re-opened to the public on 16 June 2018. Alongside the conservation, new interpretation of the Reading Abbey Quarter was installed, including a new gallery atReading Museum,and an extensive activity programme.[4][5]

Abbey WardofReading Borough Counciltakes its name from Reading Abbey, which lies within its boundaries. NowHM Prison Readingis on the site.

History[edit]

The abbey was founded byHenry Iin 1121. As part of his endowments, he gave the abbey his lands within Reading, along with land atCholsey,then in Berkshire, andLeominsterin Herefordshire. He also arranged for further land in Reading, previously given toBattle AbbeybyWilliam the Conqueror,to be transferred to Reading Abbey, in return for some of his land atAppledramin Sussex.[6][7]

Following its royal foundation, the abbey was established by a party ofmonksfromCluny AbbeyinBurgundy,together with monks from the Cluniacpriory of St PancrasatLewesin Sussex. The abbey was dedicated to theVirgin MaryandSt John the Evangelist.[8]The first abbot, in 1123, wasHugh of Amiens[9]who becamearchbishop of Rouenand was buried inRouen Cathedral.

According to the twelfth-century chroniclerWilliam of Malmesbury,the abbey was built on a gravel spur "between the rivers Kennet and Thames, on a spot calculated for the reception of almost all who might have occasion to travel to the more populous cities of England".[10]The adjacent rivers provided convenient transport, and the abbey establishedwharveson theRiver Kennet.The Kennet also provided power for the abbeywater mills,most of which were established on theHoly Brook,a channel of the Kennet of uncertain origin.

When Henry I died inLyons-la-Forêt,Normandy in 1135 his body was returned to Reading, and was buried in the front of thealtarof the then incomplete abbey.[11]

Because of its royal patronage, the abbey was one of thepilgrimagecentres ofmedievalEngland, and one of its richest and most important religious houses, with possessions as far away asHerefordshireand Scotland. The abbey also held over 230relicsincluding the hand ofSt James.[12]A shrivelled human hand was found in the ruins during demolition work in 1786 and is now in St Peter's RC Church,Marlow.[13]The songSumer is icumen in,which was first written down in the abbey about 1240, is the earliest known six-part harmony from Britain. The original document is held in theBritish Library.[14]

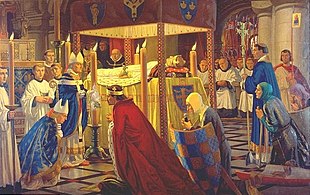

Reading Abbey was frequently visited by kings and others, most especially byHenry IIIwho often visited three or four times a year staying several weeks on each visit. It also hosted important state events, including the meeting betweenHenry IIand thePatriarch of Jerusalemin 1185, the wedding ofJohn of GauntandBlanche of Lancasterin 1359 and a meeting ofParliamentin 1453.[15]

The abbey was mostly destroyed in 1538 duringHenry VIII'sDissolution of the Monasteries.The last abbot,Hugh Faringdon,was subsequently tried and convicted ofhigh treasonandhanged, drawn and quarteredin front of the Abbey Church. After this, the buildings of the abbey were extensively robbed, with lead, glass and facing stones removed for reuse elsewhere.[2]

Some twenty years after the Dissolution, Reading town council created a new town hall by inserting an upper floor into the former refectory of thehospitiumof the abbey. The lower floor of this building continued to be used byReading School,as it had been since 1486. For the next 200 years, the old monastic building continued to serve as Reading's town hall, but by the 18th century it was suffering from structural weakness. Between 1785 and 1786, the old hall was dismantled and replaced on the same site by the first of several phases of building that were to make up today'sReading Town Hall.[16][17]Around 1787,Henry Seymour Conwayremoved a large amount of stone from the wall and used it to buildConway's Bridgenear his home atPark PlaceoutsideHenley.[18]

St James's Churchand School was built on a portion of the site of the abbey between 1837 and 1840.[19][20]Its founder was James Wheble, who owned land in the area at that time.Reading Gaolwas built in 1844 on the eastern portion of the abbey site, replacing a small county Gaol on the same site. James Wheble sold the rest of his portion of the abbey site to Reading Corporation to create theForbury Gardens,which were opened in 1861.[21][22][23]

Abbey ruins[edit]

The inner rubble cores of the walls of many of the major buildings of the abbey still stand. The only parts of the Abbey Church that still exist are fragments of the piers of the central tower, together with parts of transepts, especially the south transept. In a range to the south of this transept are, in order, the remains of thevestry,thechapter house,theinfirmarypassage and the ground floor of thedorteror monks dormitory andreredorteror toilet block. The best preserved of these ruins are those of the chapter house, which isapsidaland has a triple entrance and three great windows above. To the west of this range, the site of thecloisteris laid out as a private garden and to the south is a surviving wall of therefectory.The ruins are Grade Ilisted[24][25]and aScheduled monument[26]

Restoration[edit]

Over the years the ruins have been repaired and maintained in a piecemeal fashion leading to their deterioration.[27]In April 2008, the cloister arch, chapter house and treasury were closed to the public.[28]Repair work began in March 2009 and was expected to take only a few weeks,[29]but the entire site was instead closed in May 2009 due to the risk of falling masonry.[30]

In late 2010, Reading Borough Council was reported as estimating that the ruins could cost £3m to repair, but it was also stated that the extent of the damage was yet to be determined. A survey was carried out in October 2010, using three-dimensional scans to build up a detailed view of each elevation, thus helping to identify the extent of the conservation required.[31]In April 2011 plans for an £8m revamp were unveiled, with the aim to create an Abbey Quarter cultural area in Reading.[32]In June 2014 the Council secured initial funding from theHeritage Lottery Fund(HLF); more detailed plans for the project, Reading Abbey Revealed, were then developed and submitted to the HLF in September 2015.

In October 2014, a temporary scaffold roof, not visible from ground level, was installed on the Gateway to allow the building to dry out until funding for more permanent repairs was secured. The HLF confirmed that the second round application had been successful in December 2015.[33]The HLF supported the project with a grant of £1.77 million, with Reading Borough Council match funding of £1.38 million. Historic England provided additional grant funding for initial work to the Abbey gateway and the conservation of the refectory wall.[34]Work began in September 2016 and the ruins reopened to the public on 16 June 2018.[35][36]

Hidden Abbey Project[edit]

In spring 2014, historian-screenwriterPhilippa Langley,MBE, best known for her contribution to the exhumation ofRichard IIIin 2012, together with local historians John and Lindsay Mullaney, put together a complementary effort called the Hidden Abbey Project (HAP). The goal of the HAP was to perform a modern comprehensive study, including a non-invasive analysis of the grounds usingground-penetrating radar(GPR).[37]The first phase of the GPR survey, focusing on the Abbey Church, St James’ Church, the Forbury Gardens, and the Reading Gaol car park, began in June 2016. Initial results indicate some potential grave sites behind the high altar in an apse at the east end of the Abbey. There are also some findings probably related to the Abbey's construction, as well as some other potential archaeological targets.[38]News reports seized on the fact that the grave sites were found underneath the Ministry of Justice car park at Reading Gaol. Said the Telegraph:

Britain’s kings appear to be making a habit of this. First it was Richard III, whose bones were found under a car park in Leicester. Now it appears that Henry I may have met a similarly undignified fate.[39]

However, the borough council's press release stated, "The graves are located behind the High Altar in an apse at the east end of the Abbey. They are located east of the area where King Henry I's grave is believed to be. No direct connection between these features and King Henry can be made using these results alone."[38]

Other remains[edit]

Besides the ruins of the abbey itself, there are several other remains of the larger abbey complex still extant.

Abbey Gateway[edit]

The Abbey's Inner Gateway, also known as the Abbey Gateway, adjoinsReading Crown CourtandForbury Gardens.It is one of only two abbey buildings that have survived intact, and is agrade I listed building.The Inner Gateway marked the division between the area open to the public and the section accessible only to monks.Hugh Faringdon,the last abbot of Reading was hanged, drawn, and quartered outside the Abbey Gateway in 1539. The gateway survived because it was used as the entrance to the abbots' lodging, which was turned into a royal palace after the Dissolution. In the late 18th century, the gateway was used as part of theReading Ladies' Boarding School,attended amongst others by the novelistJane Austen.[40][41][42][43]

The gateway washeavily restoredby SirGeorge Gilbert Scott,after a partial collapse during a storm in 1861. It was extensively restored again after some decorative stonework came loose and fell into the street in 2010, reopening in 2018. The room above the gateway is now used byReading Museumas part of its learning programme for local schools, whilst the arch below is available for use by pedestrian and cycle traffic.[43]

Hospitium[edit]

The abbey'shospitium,or dormitory for pilgrims, also survives. Known as theHospitium of St. Johnand founded in 1189, the surviving building is the main building of a larger range of buildings that could accommodate 400 people. Much of the remainder of this range of buildings was located whereReading Town Hallnow stands. Today the surviving building occupies a rather isolated site, with no direct street access. It abuts the main concert hall ofReading Town Hallto the west, and the south of the building opens directly onto the churchyard ofSt Laurence's Church.The building is surrounded to the north and east by a modern office development, with a small intermediate courtyard.[44]

Abbey Mill and Holy Brook[edit]

Some remains of the former Abbey Mill are visible alongside the Holy Brook at the south of the abbey site. Thewater milloriginally belonged to Reading Abbey, whose monks are believed to have created the Holy Brook as a water supply to this and other mills owned by them and to the abbey'sfish ponds.[45][46]The Holy Brook is a 6 miles (9.7 km) long, largely artificial, watercourse which flows out of theRiver Kennetnear the village ofTheale,passes just to the south of the Abbey, and returns to its parent river just downstream of the Abbey Mill.[46]

Open-air theatre and performance[edit]

The ruins of Reading Abbey have a history of live performance. From early impromptu artist-led events, the site has established a history of open-air theatre.

In the late 1980s, the food art and performance collective La Grande Bouche organised a cabaret under marquee in the ruins. The evening offered music and performance acts combined with food, much of which cooked by contributing performers.[citation needed]

In 1994, a large scale performance event "From the Ruins"[47]was held in the abbey ruins, the finale event for the "Art in Reading" (AIR) festival, funded in part byReading Borough Council.This was organised by and featured a large number of artists and performers living or working in Reading,[48]and combined specially created music, dance, paintings, poetry and culminated in a spectacular evening performance involving large scale puppetry and pyrotechnics loosely based upon the history of Reading Abbey from the foundation by Henry I through the rise of the merchant classes to the dissolution and eventual sacking of the Abbey under Henry VIII.

In 1995, the ruined South Transept was used as the setting for the first Abbey Ruins Open Air Shakespeare production by MDM Productions andProgress Theatrein partnership with Reading Borough Council. In 1996, the outdoor production moved to the ruined chapter house and since 1999 has been staged by Progress Theatre in partnership with Reading Borough Council. This annual event expanded to the "Reading Abbey Ruins Open Air Festival" in 2007. Because of the access limitations during the restoration project, the 2009 and 2010 festivals could not be held, and the event has since relocated to the gardens ofCaversham Court.[49][50]"Shakespeare in the Ruins" returned to the Chapter House in July 2018 after the ruins reopened to the public after extensive conservation in June 2018.[51]

Abbots[edit]

As an abbey, Reading was ruled by anabbot.The abbey had 27 abbots between 1123 and 1539.[52][53]

| Abbot | Years |

|---|---|

| Hugh I (of Amiens) | 1123–1130 |

| Anscher | 1130–1135 |

| Edward | 1136–1154 |

| Reginald | 1154–1158 |

| Roger | 1158–1165 |

| William I | 1165–1173 |

| Joseph | 1173–1186 |

| Hugh II | 1186–1199 |

| Helias | 1199–1213 |

| Simon | 1213–1226 |

| Adam (of Lathbury) | 1226–1238 |

| Richard I (of Chichester) | 1238–1262 |

| Richard II (of Reading, alias Bannister) | 1262–1269 |

| Robert (of Burgate) | 1269–1290 |

| William II (of Sutton) | 1290–1305 |

| Nicholas (of Whaplode) | 1305–1328 |

| John I (of Appleford) | 1328–1342 |

| Henry (of Appleford) | 1342–1361 |

| William III (of Dombleton) | 1361–1369 |

| John II (of Sutton) | 1369–1378 |

| Richard III (of Yately) | 1378–1409 |

| Thomas I (Earley) | 1409–1430 |

| Thomas II (Henley) | 1430–1445 |

| John II (Thorne I) | 1446–1486 |

| John III (Thorne II) | 1486–1519 |

| Thomas III (Worcester) | 1519–1520 |

| Hugh III (Cook, alias Faringdon) | 1520–1539 |

Notable burials[edit]

- King Henry I

- Anne de Beauchamp, 15th Countess of Warwick

- Constance of York

- Henry fitzGerold

- Reginald de Dunstanville, 1st Earl of Cornwall

- Warin II fitzGerold

- William of Poitiers

See also[edit]

- Isle of May Priory,a community of nine Benedictine monks from Reading Abbey that was founded in 1153 on the remoteIsle of Mayin theFirth of Forthunder the patronage ofDavid I of Scotland.

References[edit]

- ^Coates, Alan (1999).English medieval books: The Reading Abbey collections from foundation to dispersal.Oxford historical monographs. Oxford: Clarendon Press.doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198207566.001.0001.ISBN978-0-19-820756-6.

- ^abThe staff of the Trust for Wessex Archaeology and Reading Museum and Art Gallery (1983).Reading Abbey Rediscovered: A summary of the Abbey's history and recent archaeological excavations.Trust for Wessex Archaeology.

- ^"Visit".readingabbeyquarter.org.uk.Reading Borough Council. 18 May 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2020.Retrieved6 February2020.

- ^"Reading Abbey Abbey ruins reopen after £3m repairs".bbc.co.uk.BBC.16 June 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2018.Retrieved24 June2018.

- ^"About the Abbey Quarter".readingabbeyquarter.org.uk.Reading Borough Council. 14 June 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2019.Retrieved25 July2019.

- ^Ditchfield, P.H.; Page, William, eds. (1923)."The borough of Reading: The borough".A History of the County of Berkshire.Vol. 3. pp. 342–364.

- ^Kemp, Brian R. (1968).Reading Abbey an introduction to the history of the abbey.Reading: Reading Museum and Art Gallery. p. 13.

- ^Charles Tomkins,Views of Reading abbey, with those of the churches originally connected with it,1805

- ^C. Warren Hollister,Henry I(2001), pp. 282–3.

- ^"History of the Abbey Quarter", Abbey Quarter

- ^Hollister, C. Warren (2003). Frost, Amanda Clark (ed.). Henry I. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. p. 474,ISBN978-0-300-09829-7

- ^Ford, David Nash (2001)."Relics from Reading Abbey".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved28 December2010.

- ^Ford, David Nash (2001)."History of Reading, Berkshire".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved28 December2010.

- ^Ford, David Nash (2001)."Sumer is icumen in memorial, Reading Abbey".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved28 December2010.

- ^Slade, Cecil (2001).The Town of Reading and its Abbey.MRM Associates Ltd. pp. 6–7.ISBN978-0-9517719-4-5.

- ^Phillips, Daphne (1980).The Story of Reading.Countryside Books. p. 42.ISBN978-0-905392-07-3.

- ^Phillips, Daphne (1980).The Story of Reading.Countryside Books. p. 88.ISBN978-0-905392-07-3.

- ^Mackay, Charles(1840).The Thames and its tributaries; or, Rambles among the rivers.London: R. Bently. p. 341.

- ^"Church of St James', Reading".British Listed Buildings.Retrieved7 June2011.

- ^"About the Nursery".Forbury Gardens Day Nursery.Retrieved7 June2011.

- ^"St James Church – A guide for Visitors"(PDF).St James Church. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 September 2007.Retrieved24 October2007.

- ^"HM Prison Service – Reading".United Kingdom Ministry of Justice.2004. Archived fromthe originalon 28 September 2007.Retrieved24 October2007.

- ^"Forbury Gardens".Reading Borough Council. 2000–2007. Archived fromthe originalon 9 January 2009.Retrieved24 October2007.

- ^"State of the Environment Report – Chapter 2 – The built environment and landscape"(PDF).Reading Borough Council. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 May 2006.Retrieved23 April2010.

- ^Ford, David Nash."Ruins of Reading Abbey".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved23 April2010.

- ^Historic England."Reading Abbey: a Cluniac and Benedictine monastery and Civil War earthwork (1007932)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved5 December2018.

- ^Fort, Linda (26 March 2010)."Reading Abbey repair costs 'truly frightening'".getreading.co.uk.Reading Post – S&B media.

- ^"Paths closed at ruins for repairs".getreading.co.uk.Reading Post – S&B media. 23 April 2008.

- ^"Repair work starts on ancient ruins".getreading.co.uk.Reading Post – S&B media. 24 March 2009.

- ^Hewitt, Adam (25 March 2010)."High cost of Abbey Ruins heritage".readingchronicle.co.uk.Berkshire Media Group.

- ^Midgley, Emma (21 October 2010)."Reading Abbey Ruins to be photographed by surveyors".BBC News.Retrieved25 October2010.

- ^"Reading Abbey ruins £8m revamp plans unveiled".BBC News.4 April 2011.Retrieved7 June2011.

- ^"Reading Abbey Quarter - The Vision".Reading Museum.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^"Reading Abbey Re-Opened to the Public".Historic England.4 July 2018.Retrieved5 December2018.

- ^"The HLF Project".Reading Museum.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^"What have we done? Reading Abbey Revealed project".Abbey Quarter.Reading Borough Council. 22 May 2018.Retrieved5 December2018.

- ^Langley, Philippa."The Hidden Abbey Project".Reading's Hidden Abbey.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^ab"A Significant Next Step Towards Revealing King Henry I's Hidden Abbey".Reading Borough Council. 12 September 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 19 September 2016.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^Sawyer, Patrick (13 September 2016)."Another car park, another King: 'Henry I's remains' found beneath tarmac at Reading Gaol".The Daily Telegraph.Retrieved15 September2016.

- ^"The Inner Gateway".The Friends of Reading Abbey.Archivedfrom the original on 25 August 2011.Retrieved7 June2011.

- ^"Abbey Gate, Reading".British Listed Buildings.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2012.Retrieved7 June2011.

- ^Ford, David Nash."The Abbey Gateway".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Archivedfrom the original on 7 February 2010.Retrieved2 May2009.

- ^ab"Abbey Gateway".readingabbeyquarter.org.uk.Reading Borough Council. 15 February 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 31 January 2020.Retrieved31 January2020.

- ^Ford, David Nash."The Hospitium".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved2 May2009.

- ^Ford, David Nash."The Abbey Mill Arch".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved2 May2009.

- ^abSowan, Adam; Castle, Sally; Hay, Peter (2003).The Holy Brook or The Granators Tale.Two Rivers Press.ISBN978-1-901677-34-8.

- ^Andrew Lewis. Video of 1994 performance 'From the Ruins', shot on Hi-8, later digitised

- ^Contributing organisations to From the Ruins as listed in contemporary project documentation in 1994

- ^"Reading Abbey Ruins Open Air Festival: History".Progress Theatre. Archived fromthe originalon 6 January 2009.Retrieved14 July2008.

- ^"About Progress Theatre".Progress Theatre.Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2017.Retrieved6 February2017.

- ^"Progress Theatre - Much Ado About Nothing".Reading Museum.Reading Borough Council.Retrieved5 December2018.

- ^Kemp, Brian R. (1968).Reading Abbey – An Introduction to the History of the Abbey.Reading, Berkshire: Reading Museum and Art Gallery.

- ^Ford, David Nash (2001)."Abbots of Reading, Berkshire".Royal Berkshire History.Nash Ford Publishing.Retrieved28 December2010.

Further reading[edit]

- Durrant, Peter; Painter, John (2018).Reading Abbey and the Abbey Quarter.Reading, Berkshire: Two Rivers Press.ISBN978-1909747395.

- Baxter, Ron (2016).The Royal Abbey of Reading.Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydel & Brewer.ISBN978-1-78327-084-2.

- Mullaney, John R. (2014).Reading's Abbey Quarter: An Illustrated History.Reading, Berkshire: Scallop Shell Press.ISBN978-0957277274.

- Cram, Leslie (1988).Reading Abbey.Reading, Berkshire: Reading Museum and Art Gallery.ISBN978-0-9501247-8-0.

- Kemp, Brian R. (1968).Reading Abbey: An Introduction to the History of the Abbey.Reading, Berkshire: Reading Museum and Art Gallery.

External links[edit]

- Cluniac monasteries in England

- Benedictine monasteries in England

- Roman Catholic churches in Reading, Berkshire

- Monasteries in Berkshire

- Grade I listed buildings in Reading

- Grade I listed monasteries

- History of Reading, Berkshire

- Ruins in Berkshire

- Tourist attractions in Reading, Berkshire

- Religious organizations established in the 1120s

- 1538 disestablishments in England

- Christian monasteries established in the 12th century

- Gates in England

- 1121 establishments in England

- Ruined abbeys and monasteries

- Grade I listed churches in Berkshire

- Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation

- Burial sites of the House of Plantagenet

- Henry I of England

- Burial sites of the House of Normandy