Richard Sorge

Richard Sorge | |

|---|---|

Sorge in 1940 | |

| Nickname(s) | Ramsay |

| Born | 4 October 1895 Baku,Baku Governorate,Caucasus Viceroyalty,Russian Empire(nowBaku,Azerbaijan) |

| Died | 7 November 1944(aged 49) Sugamo Prison,Tokyo,Empire of Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Imperial German Army Soviet Army(GRU) |

| Years of service | Germany 1914–1916, USSR 1920–1941 |

| Awards | Hero of the Soviet Union Order of Lenin Iron Cross,II class (forWorld War Icampaign) |

| Spouse(s) | Christiane Gerlach (1921–1929), Ekaterina Alexandrovna (1929(?)–1943) |

| Relations | Gustav Wilhelm Richard Sorge(father) Friedrich Sorge(great-uncle) |

Richard Sorge(Russian:Рихард Густавович Зорге,romanized:Rikhard Gustavovich Zorge;4 October 1895 – 7 November 1944) was a German journalist andSoviet military intelligenceofficer who was active before and duringWorld War IIand workedundercoveras a Germanjournalistin bothNazi Germanyand theEmpire of Japan.His codename was "Ramsay" (Рамза́й).

Sorge is known for his service inJapanin 1940 and 1941, when he provided information aboutAdolf Hitler'splan to attacktheSoviet Union.Then, in mid-September 1941, he informed the Soviets that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union in the near future. A month later, Sorge was arrested in Japan for espionage.[1][2]He was tortured, forced to confess, tried and hanged in November 1944.[3]Stalin declined to intervene on his behalf with the Japanese.[3]

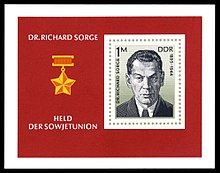

He was posthumously awarded the title ofHero of the Soviet Unionin 1964.[3]

Early life[edit]

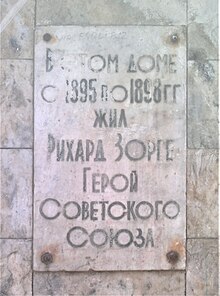

Sorge was born on 4 October 1895 in the settlement ofSabunchi,a suburb ofBaku,Baku Governorateof theRussian Empire(nowBaku, Azerbaijan).[4][5]He was the youngest of the nine children ofGustav Wilhelm Richard Sorge(1852–1907), a German mining engineer employed by theDeutsche Petroleum-Aktiengesellschaft (DPAG)and the Caucasian oil companyBranobeland his Russian wife, Nina Semionovna Kobieleva.[6]His father moved back toGermanywith his family in 1898, after his lucrative contract expired.[7]In Sorge's own words:

The one thing that made my life a little different from the average was a strong awareness of the fact that I had been born in thesouthern Caucasusand that we had moved toBerlinwhen I was very small.[8]

Sorge attendedOberrealschule Lichterfeldewhen he was six.[7]He described his father as having political views that were "unmistakably nationalist and imperialist", which he shared as a young man.[9]However, the cosmopolitan Sorge household was "very different from the averagebourgeoishome inBerlin".[10]Sorge consideredFriedrich Adolf Sorge,an associate ofKarl MarxandFriedrich Engels,to be his grandfather, but he was actually Sorge's great-uncle.[11][12]

Sorge enlisted in theImperial German Armyin October 1914, shortly after the outbreak of theFirst World War.At 18, he was posted to areserve infantrybattalion of the3rd Guards Division.He initially served on theWestern Frontand was wounded at theSecond Battle of Ypresin 1915. After a period of convalescence inBerlin,Sorge was transferred to theEastern Frontand promoted to the rank ofcorporal.He was seriously wounded again in April 1917,shrapnelsevered three of his fingers and broke both his legs, causing a lifelong limp. Afterward, Sorge was awarded theIron Cross, Second Classfor bravery. He was subsequently declared medically unfit for service and discharged from the army. After serving in the war, Sorge, who had started out in 1914 as a right-wing nationalist, became disillusioned by what he called the "meaninglessness" of the conflict and gravitated to thepolitical left.[9]

During his convalescence he read Marx, Engels andRudolf Hilferding[13]and eventually became acommunist,mainly by the influence of the father of a nurse with whom he had developed a relationship. He spent the remainder of the war studyingphilosophyandeconomicsat the universities ofKiel,BerlinandHamburg.In Kiel, he worked as an assistant to the eminentsociologistKurt Albert Gerlachand also witnessed thesailors' mutinywhich helped spark theGerman Revolution.He later joined theIndependent Social Democratic Partyand moved to Berlin, but arrived too late to participate in theSpartacist uprising.[13]

Sorge received hisdoctorateinpolitical science(Dr. rer. pol.) from Hamburg in August 1919.[14]By this time he had joined theCommunist Party of Germany(KPD), and was engaged as an activist for the party in Hamburg and subsequentlyAachen.[13]His political views got him fired from both ateachingjob andcoal miningwork.

Soviet military intelligence agent[edit]

Sorge was recruited as an agent for Soviet intelligence. With the cover of a journalist, he was sent to various European countries to assess the possibility of communist revolutions.

From 1920 to 1922, Sorge lived inSolingen,in present-dayNorth Rhine-Westphalia,Germany. He was joined there by Christiane Gerlach, the ex-wife ofKurt Albert Gerlach,a wealthy communist and professor of political science inKiel,who had taught Sorge. Christiane Gerlach later remembered about meeting Sorge for the first time: "It was as if a stroke of lightning ran through me. In this one second something awoke in me that had slumbered until now, something dangerous, dark, inescapable...".[15]

Sorge and Christiane married in May 1921. In 1922, he was relocated toFrankfurt,where he gathered intelligence about the business community. In the summer of 1923, he took part in theErste Marxistische Arbeitswoche( "First Marxist Work Week" ) Conference inIlmenau.Sorge continued his work as a journalist and also helped organize the library of theInstitute for Social Research,a new Marxist think tank in Frankfurt.[citation needed]

In 1924, he was made responsible for the security of a Soviet delegation attending the KPD's congress in Frankfurt. He caught the attention of one of the delegates,Osip Piatnitsky,a senior official with theCommunist International,who recruited him.[13]That year, he and Christiane moved to Moscow, where he officially joined theInternational Liaison Departmentof the Comintern, which was also anOGPUintelligence-gathering body. Apparently, Sorge's dedication to duty led to his divorce. In 1925, he joined theSoviet Communist Partyand received Soviet citizenship. Initially he worked as an assistant in the information department and was later the political and scientific secretary of the organizational department of theMarx–Engels–Lenin Institutein Moscow.[16]

After several years he became enmeshed in the factional struggles in the Communist movement that occurred between the death ofVladimir Leninand the consolidation of power by Joseph Stalin, being accused of supporting Stalin's last factional opponent,Nikolai Bukharin,alongside three of his German comrades.[13]However, in 1929, Sorge was invited to join theRed Army's Fourth Department (the laterGRU,or military intelligence) by department headYan Karlovich Berzin.[14][13]He remained with the Department for the rest of his life.

In 1929, Sorge went to theUnited Kingdomto study the labour movement there, the status of theCommunist Party of Great Britainand the country's political and economic conditions. He was instructed to remain undercover and to stay out of politics. In November 1929, Sorge was sent toGermany.He was instructed to join theNazi Partyand not to associate with any left-wing activists. As cover, he got a job with the agricultural newspaperDeutsche Getreide-Zeitung.[17]

China 1930[edit]

In 1930, Sorge was sent to Shanghai. His cover was his work as the editor of a German news service and for theFrankfurter Zeitung.He contacted another agent, Max Christiansen-Clausen. Sorge also met German Soviet agentUrsula Kuczynski[18]and well-known American left-wing journalistAgnes Smedley,who also worked for theFrankfurter Zeitung.She introduced Sorge toHotsumi Ozakiof the Japanese newspaperAsahi Shimbun(a future Sorge recruit) and toHanako Ishii,with whom he would become romantically involved. Sorge recruited Kuczynski as a Soviet agent and became romantically involved with her.[19]

Shortly after his arrival in China, he was able to send intelligence regarding plans byChiang Kai-shek'sNationalist governmentfor a new offensive against theChinese Communist Partyin theChinese Civil War,based largely on information gathered from German military advisors to the Nationalists.[13]

As a journalist, Sorge established himself as an expert onChinese agriculture.In that role, he travelled around the country and contacted members of theChinese Communist Party.In January 1932, Sorge reported onfighting between Chinese and Japanese troopsin the streets ofShanghai.In December, he was recalled to Moscow. His performance as an agent in Shanghai had been judged as successful by Berzin, having ensured that he and his agents had escaped detection and expanded the Soviet intelligence network.[13]

Moscow 1933[edit]

Sorge returned to Moscow, where he wrote a book about Chinese agriculture. He also married Ekaterina Maximova ( "Katya" ), a woman he had met in China and brought back with him to Russia.[citation needed]

Japan 1933[edit]

In May 1933, the GRU decided to have Sorge organize anintelligence networkin Japan. He was given the codename "Ramsay" ( "Рамзай"RamzaiorRamzay). He first went to Berlin, to renew contacts inGermanyand to obtain a new newspaper assignment in Japan as cover. In September 1931, the JapaneseKwantung Armyhad seized theManchuriaregion of China, which gave Japan another land border in Asia with the Soviet Union (previously, the Soviet Union and Japan had shared only the island ofSakhalin).[20]At the time, several Kwantung Army generals advocated following up the seizure of Manchuria by invading theSoviet Far East,and as the Soviets had broken theJapanese Armycodes, Moscow was aware of that and caused a "major Japanese war scare" in the winter of 1931–1932.[20]Until the mid-1930s, it was Japan, rather than Germany, that was considered to be the main threat by Moscow.[21]

Elsa Poretsky, the wife ofIgnace Reiss,a fellow GRU agent, commented: "His joining theNazi Partyin his own country, where he had a well documented police record was hazardous, to say the least... his staying in the very lion's den in Berlin, while his application for membership was being processed, was indeed flirting with death ".[22]

In Berlin, he insinuated himself into the Nazi Party and readNazi propaganda,particularlyAdolf Hitler'sMein Kampf.Sorge attended so manybeer hallswith his new acquaintances that he gave up drinking to avoid saying anything inappropriate. His abstinence from drinking did not make his Nazi companions suspicious. It was an example of his devotion to and absorption in his mission, as he had been a heavy drinker. He later explained toHede Massing,"That was the bravest thing I ever did. Never will I be able to drink enough to make up for this time".[23]Later, his drinking came to undermine his work.

In Germany, he received commissions from two newspapers, theBerliner Börsen Zeitungand theTägliche Rundschau,to report from Japan and the Nazi theoretical journalGeopolitik.Sorge was so successful at establishing his cover as an intensely-Nazi journalist that when he departed Germany,Joseph Goebbelsattended his farewell dinner.[9]He went to Japan via theUnited States,passing throughNew Yorkin August 1933.[24]

Sorge arrived inYokohamaon 6 September 1933. After landing in Japan, Sorge became the Japan correspondent for theFrankfurter Zeitung.As it was the most prestigious newspaper in Germany, Sorge's status as the Tokyo correspondent for theFrankfurter Zeitungmade him, in many ways, the most senior German reporter in Japan.[25]Sorge's reputation as a Nazi journalist who detested the Soviet Union served as an excellent cover for his espionage work.[25]His task in Japan was more challenging than that in China: the Soviets had very little intelligence capacity in Japan, so Sorge would have to build a network of agents from nothing, under much tighter surveillance than he had faced in Shanghai.[13]Sorge was told by his GRU superiors that his mission in Japan was to "give very careful study to the question of whether or not Japan was planning to attack the USSR".[21]After his arrest in 1941, Sorge told his captors:

This was for many years the most important duty assigned to me and my group; it would not be far wrong to say that it was the sole object of my mission in Japan.... The USSR, as it viewed the prominent role and attitude taken by the Japanese military in foreign policy after the Manchurian incident, had come to harbor a deeply implanted suspicion that Japan was planning to attack the Soviet Union, a suspicion so strong that my frequently expressed opinions to the contrary were not always fully appreciated in Moscow....[26]

He was warned by his commanders not to have contact with either the undergroundJapanese Communist Partyor the Soviet embassy inTokyo.His intelligence network in Japan included theRed Armyofficer and radio operatorMax Clausen,[27]Hotsumi Ozakiand two other Comintern agents,Branko Vukelić,a journalist working for the French magazine,Vu,and a Japanese journalist,Miyagi Yotoku,who was employed by the English-language newspaper, theJapan Advertiser.Max Clausen's wife, Anna, acted as ring courier from time to time. From summer 1937, Clausen operated under the cover of his business, M Clausen Shokai, suppliers of blueprint machinery and reproduction services. The business had been set up with Soviet funds and became a commercial success. Ozaki was a Japanese man from an influential family who had grown up inTaiwan,then a Japanese colony. He was an idealisticSinophilewho believed that Japan, which had started its modernisation with theMeiji Restoration,had much to teach China.[25]However, Ozaki was shocked by the racism of Japanese policy towards China, with the Chinese being depicted as a people fit only to be slaves. Ozaki believed that the existing political system of Japan, with the emperor being worshipped as a living god, was obsolete, and that saving Japan from fascism would require Japan being "reconstructed as a socialist state".[25]

Between 1933 and 1934, Sorge formed a network of informants. His agents had contacts with senior politicians and obtained information on Japanese foreign policy. His agent Ozaki developed a close contact with Prime MinisterFumimaro Konoe.Ozaki copied secret documents for Sorge.

As he appeared to be an ardent Nazi, Sorge was welcome at the German embassy. One Japanese journalist who knew Sorge described him in 1935 as "a typical, swashbuckling, arrogant Nazi... quick-tempered, hard-drinking".[28]As the Japan correspondent for theFrankfurter Zeitung,Sorge developed a network of sources in Japanese politics, and soon German diplomats, including the ambassadorHerbert von Dirksen,came to depend upon Sorge as a source of intelligence on the fractious and secretive world of Japanese politics.[15]The Japanese values ofhonneandtatemae(the former literally means "true sound", roughly "as things are", and the latter literally means "façade" or roughly "as things appear" ), the tendency of the Japanese to hide their real feelings and profess to believe in things that they do not, made deciphering Japan's politics difficult. Sorge's fluency in Japanese enhanced his status as a Japanologist. Sorge was interested in Asian history and culture, especially those of China and Japan, and when he was sober, he tried to learn as much as he could.[29]Meanwhile, Sorge befriended GeneralEugen Ott,the German military attaché to Japan and seduced his wife, Helma.[30]Ott sent reports back to Berlin containing his assessments of theImperial Japanese Army,which Helma Ott copied and passed on to Sorge, who passed them on to Moscow (Helma Ott believed Sorge to be working merely for the Nazi Party).[30]As the Japanese Army had been trained by a German military mission in the 19th century, German influence was strong and Ott had good contacts with Japanese officers.[30]

In October 1934, Ott and Sorge made an extended visit to the puppet "Empire ofManchukuo",which was actually a Japanese colony, and Sorge, who knew the Far East far better than Ott, wrote the report describing Manchukuo that Ott submitted to Berlin under his name.[15]As Ott's report was received favourably at both theBendlerstrasseand theWilhelmstrasse,Sorge soon became one of Ott's main sources of information about the Japanese Empire, which created a close friendship between the two.[15]In 1935, Sorge passed on to Moscow a planning document provided to him by Ozaki, which strongly suggested that Japan was not planning on attacking the Soviet Union in 1936.[28]Sorge guessed correctly that Japan wouldinvade China in July 1937and that there was no danger of a Japanese invasion ofSiberia.[28]

On 26 February 1936, anattempted military couptook place in Tokyo. It was meant to achieve a mystical "Shōwa Restoration"and led to several senior officials being murdered by the rebels. Dirksen, Ott and the rest of the German embassy were highly confused as to why it was happening and were at a loss as to how to explain the coup to the Wilhelmstrasse. They turned to Sorge, the resident Japan expert, for help.[31]Using notes supplied to him by Ozaki, Sorge submitted a report stating that theImperial Way Factionin the Japanese Army, which had attempted the coup, was younger officers from rural backgrounds. They were upset at the impoverishment of the countryside, and that the faction was not communist or socialist but just anticapitalist and believed thatbig businesshad subverted the emperor's will.[31]Sorge's report was used as the basis of Dirksen's explanation of the coup attempt, which he sent back to the Wilhelmstrasse, which was satisfied at the ambassador's "brilliant" explanation of the coup attempt.[32]

Sorge lived in a house in a respectable neighborhood in Tokyo, where he was noted mostly for heavy drinking and his reckless way of riding his motorcycle.[15]In the summer of 1936, a Japanese woman, Hanako Ishii, a waitress at a bar frequented by Sorge, moved into Sorge's house to become his common-law wife.[15]Of all of Sorge's various relationships with women, his most durable and lasting one was with Ishii. She tried to curb Sorge's heavy drinking and his habit of recklessly riding his motorcycle in a way that everyone viewed as almost suicidal.[33]An American reporter who knew Sorge later wrote that he "created the impression of being a playboy, almost a wastrel, the very antithesis of a keen and dangerous spy".[15]

Ironically, Sorge's spying for the Soviets in Japan in the late 1930s was probably safer for him than if he had been in Moscow. Claiming too many pressing responsibilities, he disobeyedJosef Stalin's orders to return to theSoviet Unionin 1937 during theGreat Purge,as he realised the risk of arrest because of hisGerman citizenship.In fact, two of Sorge's earliest GRU handlers,Yan Karlovich Berzinand his successor,Artur Artuzov,were shot during the purges.[34]In 1938, the German ambassador to Britain,Joachim von Ribbentropwas promoted to foreign minister, and to replace Ribbentrop, Dirksen was sent to London. Ribbentrop promoted Ott to be Dirksen's replacement. Ott, now aware that Sorge was sleeping with his wife, let his friend Sorge have "free run of the embassy night and day", as one German diplomat later recalled:[35]he was given his own desk at the embassy.[13]Ott tolerated Sorge's affair with his wife on the grounds that Sorge was such a charismatic man that women always fell in love with him and so it was only natural that Sorge would sleep with his wife.[36]Ott liked to call SorgeRichard der Unwiderstehliche( "Richard the Irresistible" ), as his charm made him attractive to women.[15]Ott greatly valued Sorge as a source of information about the secretive world ofJapanese politics,especially Japan's war with China, since Ott found that Sorge knew so many things about Japan that no other Westerner knew that he chose to overlook Sorge's affair with his wife.[36]

After Ott became the ambassador to Japan in April 1938, Sorge had breakfast with him daily and they discussedGerman–Japanese relationsin detail, and Sorge sometimes drafted the cables that Ott sent under his name to Berlin.[28]Ott trusted Sorge so much that he sent him out as a German courier to carry secret messages to the German consulates inCanton,Hong KongandManila.[37]Sorge noted about his influence in the German embassy: "They would come to me and say, 'we have found out such and such a thing, have you heard about it and what do you think'?"[15] On 13 May 1938, while he rode his motorcycle in Tokyo, a very-intoxicated Sorge crashed into a wall and was badly injured.[38]As Sorge was carrying around notes given to him by Ozaki at the time, if the police had discovered the documents, his cover would have been blown. However, a member of his spy ring got to the hospital and removed the documents before the police arrived.[38]In 1938, Sorge reported to Moscow that theBattle of Lake Khasanhad been caused by overzealous officers in theKwantung Armyand that there were no plans in Tokyo for a general war against the Soviet Union.[39]Unaware that his friend Berzin had been shot as a "Trotskyite"in July 1938, Sorge sent him a letter in October 1938:

Dear Comrade! Don't worry about us. Although we are terribly tired and tense, nevertheless we are disciplined, obedient, decisive and devoted fellows who are ready to carry out the tasks connected with our great mission. I send sincere greetings to you and your friends. I request you to forward the attached letter and greetings to my wife. Please, take the time to see to her welfare.[37]

Sorge never learned that Berzin had been shot as a traitor.[37]

The two most authoritative sources for intelligence for the Soviet Union on Germany in the late 1930s were Sorge andRudolf von Scheliha,the First Secretary at the German embassy inWarsaw.[39]Unlike Sorge, who believed in communism, Scheliha's reasons for spying were money problems since he had a lifestyle beyond his salary as a diplomat, and he turned to selling secrets to provide additional income.[39]Scheliha sold documents to theNKVDindicating that Germany was planning from late 1938 to turn Poland into a satellite state, and after the Poles refused to fall into line, Germany planned to invade Poland from March 1939 onward.[40]Sorge reported that Japan did not intend for theborder war with the Soviet Union that began in May 1939to escalate into all-out war.[39]Sorge also reported that the attempt to turn theAnti-Comintern Pactinto a military alliance was floundering since the Germans wanted the alliance to be directed against Britain, but the Japanese wanted the alliance to be directed against the Soviets.[41]Sorge's reports that the Japanese did not plan to invade Siberia were disbelieved in Moscow and on 1 September 1939, Sorge was attacked in a message from Moscow:

Japan must have commenced important movements (military and political) in preparation for war against the Soviet Union but you have not provided any appreciable information. Your activity seems to [be] getting slack.[39]

Wartime intelligence[edit]

Sorge supplied Soviet intelligence with information about the Anti-Comintern Pact and theGerman-Japanese Pact.In 1941, his embassy contacts made him learn ofOperation Barbarossa,the imminentAxisinvasion of the Soviet Union and the approximate date. On 30 May 1941, Sorge reported to Moscow, "Berlin informed Ott that German attack will commence in the latter part of June. Ott 95 percent certain war will commence".[15]On 20 June 1941, Sorge reported: "Ott told me that war between Germany and the USSR is inevitable.... Invest [the code name for Ozaki] told me that the Japanese General Staff is already discussing what position to take in the event of war".[15]Moscow received the reports, but Stalin and other top Soviet leaders ultimately ignored Sorge's warnings, as well as those of other sources, including early false alarms.[42]Other Soviet agents who also reported an imminent German invasion were also regarded with suspicion by Stalin.[13]

It has been rumoured that Sorge provided the exact date of "Barbarossa", but the historianGordon Prangein 1984 concluded that the closest Sorge came was 20 June 1941 and that Sorge himself never claimed to have discovered the correct date (22 June) in advance.[43]The date of 20 June was given to Sorge byOberstleutnant(Lieutenant-Colonel) Erwin Scholl, the deputy military attaché at the German embassy.[44]On a dispatch he sent theGRUon 1 June, which read, "Expected start of German-Soviet war around June 15[45]is based on information Lt. Colonel Scholl brought with him from Berlin... for Ambassador Ott ". Despite knowing that Germany was going to invade the Soviet Union sometime in May or June 1941, Sorge was still shocked on 22 June 1941, when he learned of Operation Barbarossa. He went to a bar to get drunk and repeated in English:" Hitler's a fucking criminal! A murderer. But Stalin will teach the bastard a lesson. You just wait and see! "[15]The Soviet press reported in 1964 that on 15 June 1941, Sorge had sent a radio dispatch saying, "The war will begin on June 22".[46]Prange, who despite not having access to material released by the Russian authorities in the 1990s, did not accept the veracity of that report. Stalin was quoted as having ridiculed Sorge and his intelligence before "Barbarossa":

There's this bastard who's set up factories and brothels in Japan and even deigned to report the date of the German attack as 22 June. Are you suggesting I should believe him too?[47]

In late June 1941, Sorge informed Moscow that Ozaki had learned the Japanese cabinet had decided to occupy the southern half ofFrench Indochina(nowVietnam) and that invading the Soviet Union was being considered as an option, but for the moment, JapanesePrime Minister Konoehad decided on neutrality.[15]On 2 July 1941, anImperial Conferenceattended by the emperor, Konoe and the senior military leaders approved occupying all of French Indochina and to reinforce the Kwantung Army for a possible invasion of the Soviet Union.[15]At the bottom of the report, the Deputy Head of Soviet Army General Staff Intelligence wrote, "In consideration of the high reliability and accuracy of previous information and the competence of the information sources, this information can be trusted".[15]In July 1941, Sorge reported that German Foreign MinisterJoachim von Ribbentrophad ordered Ott to start pressuring the Japanese to attack the Soviet Union but that the Japanese were resisting the pressure.[48]On 25 August 1941, Sorge reported to Moscow: "Invest [Ozaki] was able to learn from circles closest to Konoye... that the High Command... discussed whether they should go to war with the USSR. They decided not to launch the war within this year, repeat, not to launch the war this year".[15]On 6 September 1941, an Imperial Conference decided against war with the Soviet Union and ordered for Japan to start preparations for a possible war against theUnited Statesand theBritish Empire,which Ozaki reported to Sorge.[15]At the same time, Ott told Sorge that all of his efforts to get Japan to attack the Soviet Union had failed.[15]On 14 September 1941, Sorge reported to Moscow, "In the careful judgment of all of us here... the possibility of [Japan] launching an attack, which existed until recently, has disappeared...."[15]Sorge advised the Red Army on 14 September 1941 that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union until:

- Moscow had been captured.

- TheKwantung Armyhad become three times the size of Soviet Far Eastern forces.

- A civil war had started in Siberia.[49]

This information made possible the transfer of Soviet divisions from the Far East, although the presence of theKwantung ArmyinManchurianecessitated the Soviet Union's keeping a large number of troops on the eastern borders...[50]

Various writers have speculated that the information allowed the release of Siberian divisions for theBattle of Moscow,where the German Army suffered its first strategic defeat in the war. To that end, Sorge's information might have been the most important military intelligence work in World War II. However, Sorge was not the only source of Soviet intelligence about Japan, as Soviet codebreakers had broken the Japanese diplomatic codes and so Moscow knew fromsignals intelligencethat there would be no Japanese attack on the Soviet Union in 1941.[51]

Another important item allegedly reported by Sorge may have affected theBattle of Stalingrad.Sorge reported that Japan would attack the Soviet Union from the east as soon as the German army captured any city on theVolga.[52]

Sorge's rival and opponent in Japan andEast AsiawasIvar Lissner,an agent of the GermanAbwehr.[53]

Arrests and trials[edit]

As the war progressed, Sorge was in increasing danger but continued his service. His radio messages were enciphered with unbreakableone-time pads,which were always used by the Soviet intelligence agencies and appeared as gibberish. However, the increasing number of the mystery messages made the Japanese begin to suspect that an intelligence ring was operating. Sorge was also coming under increasing suspicion inBerlin.By 1941, the Nazis had instructed SSStandartenführerJosef Albert Meisinger,the "Butcher of Warsaw", who was by then theGestaporesidentat the German embassy inTokyo,to begin monitoring Sorge and his activities. Sorge was able, through one of his lovers, Margarete Harich-Schneider, a German musician living in Japan, to gain the key to Meisinger's apartment since it had once been her apartment.[54]Much to his relief, he learned that Meisinger had concluded that the allegations that Sorge was a Soviet agent were groundless, and Sorge's loyalty was to Germany.[54]Sorge befriended Meisinger by playing on his principal weakness, alcohol, and spent much time getting him drunk, which contributed to Meisinger's favourable evaluation of Sorge.[54]Meisinger reported to Berlin that the friendship between Ott and Sorge "was now so close that all normal reports from attachés to Berlin became mere appendages to the overall report written by Sorge and signed by the Ambassador".[15]TheKempeitai,the Japanese secret police, intercepted many messages and began to close in against the German Soviet agent. Sorge's penultimate message to Moscow in October 1941 reported, "The Soviet Far East can be considered safe from Japanese attack".[55]In his last message to Moscow, Sorge asked to be sent back to Germany, as there was no danger of a Japanese attack on the Soviet Union, and he wished to aid the Soviet war effort by providing more intelligence about the German war effort.[55]Ozaki was arrested on 14 October 1941 and immediately interrogated. As theKempeitaitrailed Sorge, it discovered that Ott's wife was a regular visitor to Sorge's house and that he had spent his last night as a free man sleeping with her.[55]

Sorge was arrested shortly thereafter, on 18 October 1941, in Tokyo. The next day, a brief Japanese memo notified Ott that Sorge had been swiftly arrested "on suspicion of espionage", together with Max Clausen. Ott was both surprised and outraged as a result and assumed that it was a case of "Japanese espionage hysteria". He thought that Sorge had been discovered to have passed secret information on the Japan-American negotiations to the German embassy and also that the arrest could have been caused byanti-German elementswithin the Japanese government. Nonetheless, he immediately agreed with Japanese authorities to "investigate the incident fully".[56]It was not until a few months later that Japanese authorities announced that Sorge had actually been indicted as a Soviet agent.[57]

He was incarcerated inSugamo Prison.Initially, the Japanese believed, because of his Nazi Party membership and German ties, that Sorge had been anAbwehragent. However, theAbwehrdenied that he had been one of their agents. Under torture, Sorge confessed, but the Soviet Union denied he was a Soviet agent. The Japanese made three overtures to the Soviet Union and offered to trade Sorge for one of their own spies. However, the Soviet Union declined all of the Japanese attempts and maintained that Sorge was unknown to them.[58][59] In September 1942, Sorge's wife, Katya Maximova, was arrested by the NKVD on the charges that she was a "German spy" since she was married to the German citizen Sorge (the fact that Sorge was a GRU agent did not matter to the NKVD), and she was deported to thegulag,[60]where she died in 1943.[15]Hanako Ishii, the Japanese woman who loved Sorge and the only woman whom Sorge loved in return, was the only person who tried to visit Sorge during his time in Sugamo Prison.[61]During one of her visits, she expressed concern that Sorge, under torture by theKempeitai,would name her as involved in his spy ring, but he promised her that he would never mention her name to theKempeitai.[62]TheKempeitaiwas much feared in Japan for its use of torture as an investigation method. Sorge ultimately struck a deal with theKempeitaithat if it spared Ishii and the wives of the other members of the spy ring, he would reveal all.[15]Ishii was never arrested by theKempeitai[15]Sorge told hisKempeitaicaptors:

That I successfully approached the German embassy in Japan and won the absolute trust by people there was the foundation of my organisation in Japan.... Even in Moscow that fact that I infiltrated into the centre of the embassy and made use of it for my spying activity is evaluated as extremely amazing, having no equivalent in history.[9]

After the arrest of Sorge, Meisinger used the increased spy fear of the Japanese to fraudulently denounce "anti-Nazis" as "Soviet spies" to the Japanese authorities. He was responsible for the persecution, the internment and the torture of the "Schindler"of Tokyo,Willy Rudolf Foerster.[63]Foerster was forced to sell his company, which had employed a sizable number ofJewish refugees from Germanyand the countries occupied by Germany. He and his Japanese wife survived, but after the war, the same former German diplomats, who had denounced and persecuted him as an "anti-Nazi", would discredit him.[64]

Death[edit]

Sorge was hanged on 7 November 1944, at 10:20 Tokyo time inSugamo Prisonand was pronounced dead 19 minutes later.[65]Hotsumi Ozaki had been hanged earlier in the same day. Sorge's body was not cremated because of wartime fuel shortages. He was buried in a mass grave for Sugamo Prison inmates in the nearbyZoshigaya Cemetery.[66]

Sorge was survived by his mother, then living in Germany, and he left his estate to Anna Clausen, the wife of his radio operator, Max Christiansen-Clausen.[66]

After hounding theAmerican occupation authorities,Sorge's Japanese lover, Hanako Ishii ( giếng đá ăn màyIshii Hanako,1911 – 1 July 2000), located and recovered his skeleton on 16 November 1949. After identifying him by his distinctive dental work and a poorly-set broken leg, she took his body away and had him cremated at the Shimo-Ochiai Cremation Centre. She kept his own teeth, belt and spectacles and had made a ring of his gold bridgework, which she wore for the rest of her life.[67]After her death, her own ashes were interred beside his. A white memorial stone at the site bears an epitaph in Japanese, the first two lines read: "Here lies a hero who sacrificed his life fighting against war and for world peace".[68]

The Soviet Union did not officially acknowledge Sorge until 1964.[69]

It was argued that Sorge's biggest coup led to his undoing because Stalin could not afford to let it become known that he had rejected Sorge's warning about the German attack in June 1941. However, nations seldom officially recognise their own undercover agents.[70]

Posthumous recognition[edit]

Initially, Sorge's reputation inWest Germanyin the 1950s was highly negative, with Sorge depicted as a traitor working for the Soviet Union who was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands ofWehrmachtsoldiers in the winter of 1941–1942.[71]The 1950s were a transition moment in the German memory of Nazi Germany, as its German supporters sought a version of history that presented them as victims, rather than as followers, of Hitler. They portrayed Nazism as an aberration in German history that had no connections to traditionalPrussian virtues,falsely portrayedtheWehrmachtas an honourable fighting forcethat had nothing to do with theHolocaustand presented the Soviets as guilty of crimes that were even more horrific than those committed by the Nazis.[72]That way of remembering the Nazi past in the 1950s caused Operation Barbarossa and Germany's war on the Eastern Front to be seen as a heroic and legitimate war against the Soviet Union of which Germans should be unashamed.[72]

The first tentative efforts at changing the memory of the Nazi past started in the early 1950s, when German PresidentTheodor Heussgave a speech on 20 July 1954 that praised theputschattempt of 20 July 1944. He argued that "themen of July 20th"were patriots rather than traitors, which was then a bold gesture.[73]The first effort to present Sorge in a positive light occurred in the summer of 1953, when the influential publisherRudolf Augsteinwrote a 17-part series in his magazine,Der Spiegel.He argued that Sorge was not a Soviet agent but a heroic German patriot opposed to the Nazi regime whose motivation in providing intelligence to the Soviet Union was to bring down Hitler, rather than to support Stalin.[74]Augstein also attacked Willoughby for his bookThe Shanghai Conspiracythat claimed that Sorge had caused the "loss of China" in 1949 and that the Sorge spy ring was in the process of taking over the U.S. government. Augstein argued that Willoughby and his fans had completely misunderstood that Sorge's espionage was directed against Germany and Japan, not the U.S.[74]

Such was the popularity of Augstein's articles that the German authorHans Hellmut Kirstpublished a spy novel featuring Sorge as the hero, andHans-Otto Meissnerwrote the bookDer Fall Sorge(The Sorge Case) that was a cross between a novel and a history by blending fact and fiction together with a greater emphasis on the latter.[74]Meissner had served as third secretary at the German Embassy in Tokyo and had known Sorge.[74]Meissner's book, which was written as a thriller that engaged in "orientalism",portrayed Japan as a strange, mysterious country in which the Enigma tic and charismatic master spy Sorge operated to infiltrate both its government and the German embassy.[71]Meissner presented Sorge as the consummate spy, a cool professional who was dressed in a rumpled trench coat and fedora and was a great womanizer, and much of the book is concerned with Sorge's various relationships.[75]

Later on, Meissner presented Sorge as a rathermegalomaniacfigure and, in the process, changed Sorge's motivation from loyalty to communism to colossal egoism. He had Sorge rant about his equal dislike for both Stalin and Hitler and had him say that he supplied only enough information to both regimes to manipulate them into destroying each other since it suited him to play one against the other.[76]At the book's climax, Sorge agreed to work for the AmericanOffice of Strategic Services,in exchange for being settled inHawaii,and he was in the process of learning that Japan is planning on bombing Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, but his love of women proved to be his undoing as the Japanese dancer Kiyomi rejected his sexual advances.[77]Sorge finally seduced Kiyomi but lost valuable time, which allowed theKempeitaito arrest him.[77]

The American historian Cornelius Partsch noted some striking aspects of Meissner's book such as his complete exoneration of theAuswärtiges Amtfrom any involvement in the criminal aspects of the Nazi regime. Meissner had Sorge constantly breaking into offices to steal information, which he did not do, as security at the German embassy was sloppy, and Sorge was trusted as an apparently-dedicated Nazi journalist and so breaking into offices would have been unnecessary. Meissner avoided any mention of SSStandartenführerJosef Albert Meisinger, the "Butcher of Warsaw" who was stationed at the German embassy as the police attaché to Japan.[78]Partsch wrote that Meissner gave Sorge almost-superhuman abilities at lockbreaking, as he broke into various offices, safes and filing cabinets with the greatest ease, but in reality, secret documents were all too often left out in the open in unlocked rooms, and Sorge was allowed to wander about the embassy without an escort.[79]Meissner portrayed theAuswärtiges Amtin the traditional manner, as a glamorous, elitist group that operated in exotic places like Japan serving Germany, not the Nazi regime.[79]

Kirst's bookDie letzte Karte spielt der Todwas a novel that offered a considerably more realistic picture than Meissner's romanticised portrayal of Sorge.[80]Kirst portrayed Sorge as anexistentialhero, a deeply-traumatized veteran of World War I, whose sleep was constantly disturbed by horrific nightmares of his war service, and when he was awake, he suffered from frequent panic attacks.[80]Kirst's book depicted Sorge as a "lonely, desperate" man, a tragic, wounded individual with a reckless streak who engaged in maniacal binge drinking, nearly-suicidal motorcycle riding across the Japanese countryside, and though he wanted love, he was incapable of maintaining lasting relationships.[80]Unlike Meissner, Kirst had Meisinger appear as one of the book's villains by portraying him as an especially-loathsome and stupid SS officer, who fully deserved to be deceived by Sorge.[80]As part of Kirst's portrayal of Sorge as a tragic man on the brink and as victim led him to portray Sorge's spying for the Soviet Union by forces beyond his control.[80]Kirst was more forceful in his condemnation of National Socialism than Meissner as his book maintained that the regime was so monstrously evil that an existential man forever on the brink of a mental breakdown like Sorge ended up spying for the Soviet Union as the lesser evil.[80]

Partsch noted that both books were very much concerned with Sorge's womanising, which neither author exaggerated, but presented the aspect of his personality in different ways. Kirst portrayed Sorge's womanizing as part of the same self-destructive urges that led him to spy for the Soviet Union, but Meissner depicted Sorge's womanizing as part of his callousnarcissismand as his principal weakness, as his desire for Kiyomi finally destroyed him.[81]In turn, that led to different depictions of the male body. Meissner portrayed it as the seductive instrument that entices female desire and led women into ill-advised relationships with Sorge, whose body is perfectly fit and attractive to women.[82]Kirst, by contrast, correctly noted that Sorge walked with a pronounced limp because of a war wound, which had Sorge sarcastically say was because of his "gallantry" in his book, and Sorge's wounded body served as ametaphorfor his wounded soul.[81]Partsch further commented that Meissner's book was a depoliticised and personalised account of the Sorge spy ring, as he omitted any mention ofHotsumi Ozaki,an idealistic man who sincerely believed his country was on the wrong course, and he portrayed Sorge as a "Faustianman "motivated only by his vanity to exercise" a god-like power over the world "and gave Sorge" an overblown, pop-Nietzscheansense of destiny ".[81]

The ultimate "message" of Meissner's book was that Sorge was an amoral, egoistical individual whose actions had nothing to do with ideology and that the only reason for Germany's defeat by the Soviet Union was Sorge's spying, which suggested that Germany lost the war only because of "fate".[81]Meissner followed the "great man" interpretation of history that a few "great men" decide the events of the world, with everyone else reduced to passive bystanders.[80]By contrast, Kirst pictured Sorge as a victim, as a mere pawn in a "murderous chess game" and emphasised Sorge's opposition to the Nazi regime as the motivation for his actions.[81]Kirst further noted that Sorge was betrayed by his own masters as after his arrest, and the Soviet regime denounced him as a "Trotskyite" and made no effort to save him.[81]Partsch concluded that the two rival interpretations of Sorge put forward in the novels by Meissner and Kirst in 1955 have shaped Sorge's image in the West, especially Germany, ever since their publication.[83]

In 1954, theWest Germanfilm directorVeit Harlanwrote and directed the filmVerrat an Deutschlandabout Sorge's espionage in Japan. Harlan had been the favourite filmmaker of Nazi Information MinisterJoseph Goebbelsand directed many propaganda films, includingJud Süss.Harlan's film is a romantic drama, starring Harlan's wife,Kristina Söderbaum,as Sorge's love interest. The film was publicly premiered by the distributor before it passed the rating system and so was withdrawn from more-public performances and finally released after some editing had been done.[84]

In 1961, a movie,Who Are You, Mr. Sorge?,was produced in France in collaboration with West Germany,Italy,and Japan. It was very popular in the Soviet Union as well. Sorge was played byThomas Holtzmann.

In November 1964, twenty years after his death, the Soviet government awarded Sorge with the title ofHero of the Soviet Union.[85]Sorge's widow, Hanako Ishii, received a Soviet and Russian pension until her death in July 2000 in Tokyo.[58]In the 1960s, theKGB,seeking to improve its image in the Soviet Union, began the cult of the "hero spy" with formerChekistsworking abroad being celebrated as the great "hero spies" in books, films and newspapers. Sorge was one of those selected for "hero spy" status. In fact, the Soviets had broken Japanese codes in 1941 and had already known independently of the intelligence provided by Sorge that Japan had decided to "strike south" (attacking the United States and the British Empire), instead of "striking north" (attacking the Soviet Union).[51]

The Kremlin gave much greater attention to signals intelligence in evaluating threats from Japan from 1931 to 1941 than it did to the intelligence that was gathered by the Sorge spy ring, but since Soviet intelligence did not like to mention the achievements of its codebreakers, Soviet propaganda from 1964 onward gloried Sorge as a "hero spy" and avoided all mention that the Soviets had broken the Japanese codes.[86]The Soviets, during theCold War,liked to give the impression that all of their intelligence came fromhuman intelligence,rather thansignals intelligence,to prevent Western nations from knowing how much the Soviets collected from the latter source.[87]A testament to Sorge's fame in the Soviet Union was that even though Sorge worked for the GRU, not the NKVD, it was the KGB, which had far more power than the Red Army, that claimed him as one of its "hero spies" in the 1960s.[88]

In 1965, threeEast Germanjournalists publishedDr Sorge funkt aus Tokyoin celebration of Sorge and his actions. Before the award, Sorge's claim that Friedrich Adolf Sorge was his grandfather was repeated in the Soviet press.[89]In a strange Cold War oddity, the authors stirred up a free speech scandal with patriotic letters to former Nazis in West Germany, which caused theVerfassungsschutzto issue a stern warning in early 1967: "If you receive mail from a certainJulius Mader,do not reply to him and pass on the letter to the respective security authorities ". [90]In 1971, a comic book based on Sorge's life,Wywiadowca XX wieku( "20th Century Intelligence Officer" ), was published in thePeople's Republic of Polandto familiarise younger readers with Sorge.

There is a monument to Sorge inBaku, Azerbaijan.[91]Sorge also appears inOsamu Tezuka'sAdolfmanga.In his 1981 book,Their Trade is Treachery,the authorChapman Pincherasserted that Sorge, a GRU agent himself, recruited the EnglishmanRoger HollisinChinain the early 1930s to provide information. Hollis later returned to England, joinedMI5just beforeWorld War IIbegan and eventually became the director-general of MI5 from 1956 to 1965. As detailed by former MI5 stafferPeter Wrightin his 1988 bookSpycatcher,Hollis was accused of being a Soviet agent, but despite several lengthy and seemingly-thorough investigations, no conclusive proof was ever obtained.

One ofAleksandar Hemon's first stories in English is "The Sorge Spy Ring" (TriQuarterly,1997). The 2003 Japanese filmSpy Sorge,directed byMasahiro Shinoda,details his exploits in Shanghai and in Japan. In the film, he is portrayed by the Scottish actorIain Glen.In 2016, one of Moscow'sMoscow Central Circlerail stations was named after Sorge (Zorge). A Russian television series, "Richard Sorge. Master Spy", was a twelve-episode series filmed in 2019.[92]

Reputation[edit]

Comments about Sorge by famous personalities include:[93][better source needed]

- "A devastating example of a brilliant success of espionage". –Douglas MacArthur,General of the Army[94]

- "His work was impeccable." –Kim Philby

- "In my whole life, I have never met anyone as great as he was." – Mitsusada Yoshikawa, Chief Prosecutor in the Sorge trials who obtained Sorge's death sentence.

- "Sorge was the man whom I regard as the most formidable spy in history." –Ian Fleming

- "Richard Sorge was the best spy of all time." –Tom Clancy

- "The spy who changed the world". –Lance Morrow

- "Somehow, amidst the Bonds andSmiley's People,we have ignored the greatest of 20th century spy stories – that of Stalin's Sorge, whose exploits helped change history. "–Carl Bernstein

- "Richard Sorge's brilliant espionage work saved Stalin and the Soviet Union from defeat in the fall of 1941, probably prevented a Nazi victory in World War II and thereby assured the dimensions of the world we live in today." –Larry Collins

- "The spies in history who can say from their graves, the information I supplied to my masters, for better or worse, altered the history of our planet, can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Richard Sorge was in that group." –Frederick Forsyth

- "Stalin's James Bond". –Le Figaro

In popular culture[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(September 2021) |

There have been several literary and dramatic representations of Sorge's life:

- The GermanLetzte Karte spielt der TodbyHans Hellmut Kirst,published in English asThe Last Card(New York: Pyramid Publications, Inc., 1967) andDeath Plays the Last Card(London: Fontana, 1968).

- The German filmVerrat an Deutschland(1955), directed byVeit Harlanand starringPaul Mulleras Sorge.

- The French docu-dramaWho Are You, Mr. Sorge?(1961), written byYves Ciampi,Tsutomu Sawamura, andHans-Otto Meissner,starringThomas Holtzmannas Sorge.

- Wywiadowca XX wieku(20th-Century Intelligencer), a comic book that narrated Sorge's exploits, published in Poland in 1983.

- The American novelWild Midnight Falls(Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1968) in the Milo March series by M. E. Chaber, based on the supposition that Sorge was still alive and secretly active.

- The Russian novelКио ку мицу! Совершенно секретно - при опасности сжечь!(Kio ku mitsu! Top secret - burn in case of danger!) by Ю. М. Корольков[95](Yu. M. Korol'kov) (Беларусь, 1987).

- The FrenchL'Insenséby Morgan Sportes (Grasset, 2002) translated into Japanese asSorge hametsu no fuga(Iwanami Shoten, 2005).

- The 1997 novelStepperby AustralianBrian Castro.

- "The Sorge Spy Ring", in the 2000 short story collectionThe Question of BrunobyAleksandar Hemon.

- The later chapters ofOsamu Tezuka's mangaAdolf.

- The Japanese filmSpy Sorge(2003), directed byMasahiro Shinodaand starringIain Glenas Sorge.

- The BookThe Man with Three Facesby GermanHans-Otto Meissner,who wrote it based in his experiences as a diplomat in wartime. He met Sorge on some occasions.

- The Russian television mini-seriesZorge(2019)[96]

- An Impeccable Spy,biography by Owen Matthews, 2019.

References[edit]

- ^Варшавчик, Сергей (Varshavchik, Sergey) (4 October 2015)."Рихард Зорге: блестящий разведчик, влиятельный журналист"[Richard Sorge: brilliant intelligence agent, influential journalist].RIA Novosti(in Russian).Retrieved4 January2020.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^"'Гении разведки': вышла новая книга о тех, кто добывал секреты для России "['Intelligence geniuses': a new book about those who mined secrets for Russia was published].RIA Novosti(in Russian). 17 January 2019.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^abcSimkin, John (January 2020)."Richard Sorge".Spartacus Educational.

- ^"Зорге Рихард".

- ^hrono.ru. Richard Sorge

- ^Deakin & Storry 1966,p. 23

- ^ab"Herr Sorge saß mit zu Tisch – Porträt eines Spions".Spiegel Online.Vol. 24. 13 June 1951.Retrieved30 April2019.

- ^Partial Memoirs of Richard Sorge, Part 2, p. 30; quoted in part by Prange according to whom Sorge was 11 when the family moved (Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984) and in full by Whymant according to whom Sorge was two years old at the time of the move (Whymant 2006,p. 11); Whymant refers to a "glimmering memory of this ambiance [in the southern Caucasus]" as staying with Sorge for the rest of his life which rather suggests that two years old is a somewhat low estimate of Sorge's age at the time of the move.

- ^abcdAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,p. 137

- ^Whymant 2006,p. 12

- ^Deakin & Storry 1966,pp. 23–24; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Whymant 2007,p. 13.

- ^abcdefghijkFinn, Daniel (22 June 2021)."The Secret Life of Communist Richard Sorge, Hitler's Nemesis and the World's Greatest Spy".Jacobin.Retrieved4 July2021.

- ^abPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwGoldman, Stuart (30 July 2010)."The Spy Who Saved the Soviets".History Net.Retrieved3 June2017.

- ^"Институт геополитики профессора Дергачева - Цивилизационная геополитика (Геофилософия)".25 February 2022. Archived fromthe originalon 25 February 2022.Retrieved23 December2023.

- ^Deakin & Storry 1966,p. 63

- ^Richard C.S. Trahair. Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies and Secret Operations.Greenwood Publishing Group (2004);ISBN0-313-31955-3

- ^"FindArticles – CBSi".

- ^abAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 140

- ^abAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 138

- ^Deacon, Richard (1987).A history of the Russian secret service(Rev. ed.). London: Grafton. p. 334.ISBN0-586-07207-1.OCLC59238054.

- ^Hede Massing,This Deception(New York, 1951), p. 71; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Whymant 2006,pp. 40–43

- ^abcdAllen & Polmar 1997,p. 523.

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 138–139

- ^His name is often spelt with an initialK,but "Clausen" appears on his driving licence and as his signature. Charles A. Willoughby,Shanghai Conspiracy(New York, 1952), photograph at p. 75; referred to byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^abcdAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 139

- ^Johnson 1990,p. 70

- ^abcAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 178

- ^abJohnson 1990,p. 170

- ^Johnson 1990,pp. 170–171

- ^Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984,p. 158 & 225.

- ^Bagley 2013,pp. 159–160

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 239

- ^abKingston, Jeff (1 November 2014)."Commemorating wartime Soviet spy Sorge".Japan Times.Retrieved3 June2017.

- ^abcAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 191

- ^abJohnson 1990,p. 12

- ^abcdeAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 192

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 192–193

- ^Weinberg, Gerhard (1980).The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Volume 2 Starting World War Two 1937-1939.University of Chicago Press. p. 551.

- ^"Books: Murray Polner: Review of David E. Murphy's What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa (Yale University Press, 2005) and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa's Racing The Enemy: Stalin, Truman, & the Surrender of Japan (Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2005)".Archived fromthe originalon 19 July 2009.Retrieved20 July2009.

- ^Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984,p. 347

- ^Obi Toshito, ed.,Gendai-shi Shiryo, Zoruge Jiken(Materials on Modern History, The Sorge Incident) (Tokyo, 1962), Vol. I, p.274; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Broekmeyer, M. J.; Broekmeyer, Marius (2004).Stalin, the Russians, and Their War.Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 31.ISBN978-0-299-19594-6.

- ^I. Dementieva and N. Agayantz, "Richard Sorge, Soviet Intelligence Agent",Sovietskaya Rossiya,6 September 1964; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Simon Sebag MontefioreStalin: The Court of the Red Tsar(London, 2003), p. 360; referred to in the Notes below as "Sebag Montefiore"

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 270

- ^Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984,p. 407

- ^Mayevsky, Viktor, "Comrade Richard Sorge",Pravda,4 September 1964; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^abAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 271

- ^Whymant 2006,p. 206

- ^Juergen Corleis (March 2008).Always on the Other Side: A Journalist's Journey from Hitler to Howard's End.Juergen Corleis. p. 59.ISBN978-0-646-48994-0.Retrieved23 April2012.

- ^abcPartsch 2005,p. 642.

- ^abcAndrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 219

- ^Toland, John(1970),The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936–1945,Random House, p. 122,ISBN0-394-44311-X

- ^Whymant 2006,p. 283

- ^abSakaida, Henry; Christa Hook (2004).Heroes of the Soviet Union 1941–45.Osprey Publishing. p. 32.ISBN1-84176-769-7.

- ^Trepper, Leopold (1977).The Great Game.Mc Grew Hill. p. 378.ISBN0070651469.

- ^Goldman, Stuart (30 July 2010)."The Spy Who Saved the Soviets".History Net.Retrieved3 June2017.

- ^Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984,p. 326.

- ^Prange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984,p. 425.

- ^Jochem 2017,pp. 181ff.

- ^Jochem 2017,pp. 96–112.

- ^Hastings 2015,p. 183

- ^abInterview with Sorge's defence lawyer Sumitsugu Asanuma conducted on Prange's behalf by Ms. Chi Harada, quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Hastings 2015,p. 542

- ^Saito, Katsuhisa (30 June 2018).ゾルゲが người yêu と miên る nhiều ma linh viên: Vân nói の スパイ の dấu chân を phóng ねて[Tama Cemetery where Sorge sleeps with his lover: Visit the footsteps of a legendary spy].nippon(in Japanese).Retrieved28 June2022.

- ^Johnson, Chalmers (11 October 1964),"Again The Sorge Case",New York Times,retrieved4 May2017

- ^Corkill, Edan (31 October 2010)."Sorge's spy is brought in from the cold".The Japan Times.Retrieved28 June2022.

- ^abPartsch 2005,p. 636–637.

- ^abPartsch 2005,p. 632–636.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 635.

- ^abcdPartsch 2005,p. 637.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 638.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 639–640.

- ^abPartsch 2005,p. 640.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 642–643.

- ^abPartsch 2005,p. 643.

- ^abcdefgPartsch 2005,p. 644.

- ^abcdefPartsch 2005,p. 645.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 644–645.

- ^Partsch 2005,p. 646.

- ^Müller, Erika (20 January 1955)."Die rote und die goldene Pest: Der Fall Sorge oder Harlans" Verrat an Deutschland "– Bausch schrieb einen Brief".Die Zeit.Retrieved9 February2017.

- ^Heroes of the Soviet Union;Sorge, Richard(in Russian)

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 139 & 271

- ^Andrew & Gordievsky 1990,pp. 271–272

- ^Andrew & Mitrokhin 2000,p. 366–367.

- ^Mayevsky, Viktor, "Comrade Richard Sorge",Pravda,4 September 1964, p. 4; quoted byPrange, Goldstein & Dillon 1984

- ^Industrie-Warndienst,Bonn/Frankfurt/Main, Nr. 12 vom 21. April 1967, cit. nach Julius Mader: Hitlers Spionagegenerale sagen aus, 5. Aufl. 1973, S.9f

- ^"Baku, Azerbaijan: 10 of the city's weirdest tourist attractions".The Telegraph.3 February 2016.

- ^Richard Sorge. Master Spy -Zorge (original title)imdb,accessed 3 November 2020

- ^Sorge A chronology Edited by Michael Yudellrichardsorge,accessed 3 November 2020

- ^How Unpaid Master Spy Changed History.1956.

- ^ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА -[ Проза ]- Корольков Ю.М. Кио ку мицу!

- ^Richard Sorge. Master Spy Zorge (original title),IMDd, accessed 3 November 2020

Bibliography[edit]

- Allen, Thomas; Polmar, Norman (1997),The Spy Book,New York: Random House,ISBN0-375-70249-0

- Andrew, Christopher; Gordievsky, Oleg (1990),KGB: The Inside Story of Its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev,New York: Harper Collins,ISBN0060166053

- Andrew, Christopher; Mitrokhin, Vasili (2000),The Mitrokhin Archive,London: Penguin Books,ISBN0465003125

- Messana, Paola (2011),Soviet Communal Living: An Oral History of the Kommunalka,New York: Palgrave Macmillan,ISBN978-0-230-11016-8

- Bagley, Tennent (2013),Spymaster: Startling Cold War Revelations of a Soviet KGB Chief,New York: Skyhorse Publishing,ISBN978-1-62636-065-5

- Deakin, F. W.; Storry, G. R. (1966),The case of Richard Sorge,London: Chatto & Windus.An early account by two leading British historians of the time. It is informed by their differing perspectives, Deakin being an authority on 20th century European history and Storry an authority on 20th century Japan.

- Hastings, Max (2015),The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939–1945(Paperback), London: William Collins,ISBN978-0-00-750374-2

- Johnson, Chalmers (1990).An Instance of Treason: Ozaki Hotsumi and the Sorge Spy Ring.Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-1767-0.

- Matthews, Owen(2020).Impeccable Spy: Richard Sorge, Stalin's Master Agent.London; New York: Bloomsbury.ISBN978-1408857816.

- Meissner, Hans-Otto(1955),The Man with Three Faces. The True Story of a Master Spy,New York: Rinehart;translation ofDer Fall Sorge(Mǖnchen: Wilhelm Andermann 1955).

- Partsch, Cornelius (Winter 2005), "The Case of Richard Sorge: Secret Operations in the German past in 1950s Spy Fiction",Monatshefte,97(4): 628–653,doi:10.3368/m.XCVII.4.628,S2CID219196501

- Prange, Gordon W.;Goldstein, Donald M.; Dillon, Katherine V. (1984),Target Tokyo: The Story of the Sorge Spy Ring,New York: McGraw-Hill,ISBN0-07-050677-9

- Whymant, Robert(1996),Stalin's Spy: Richard Sorge and the Tokyo Espionage Ring,London: I.B. Tauris Publishers,ISBN1-86064-044-3

- Whymant, Robert(2006) [1996],Stalin's Spy: Richard Sorge and the Tokyo Espionage Ring,New York: Palgrave MacMillan,ISBN1-84511-310-1

- Whymant, Robert (9 January 2007).Stalin's Spy: Richard Sorge and the Tokyo Espionage Ring.I.B.Tauris.ISBN978-1-84511-310-0.Retrieved31 August2013.

- Jochem, Clemens (2017),Der Fall Foerster: Die deutsch-japanische Maschinenfabrik in Tokio und das Jüdische Hilfskomitee,Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich,ISBN978-3-95565-225-8

Further reading[edit]

- Kirst, Hans Helmut.'Death Plays The Last Card': The Tense, Brilliant Novel of Richard Sorge—World War II's Most Daring Spy.Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn. Collins Fontana paperback, 1968.

- Meissner, Hans-Otto.The Man with Three Faces: Sorge, Russia's Master Spy.London: Pan # GP88, 1957, 1st Printing Mass Market Paperback.

- Rimer, J. Thomas. (ed.)Patriots and Traitors, Sorge and Ozaki: A Japanese Cultural Casebook.MerwinAsia, 2009. (paperback,ISBN978-1-878282-90-3). Contains several essays on the spy ring, a translation of selected lettersHotsumi Ozakiwrote in prison, and the translation ofJunji Kinoshita's 1962 playA Japanese Called Otto.

External links[edit]

- The 2003 Japanese movieSpy Sorgeabout Richard Sorge's life includes some scenes shot inKitakyushu,including one at theWest Japan Industrial ClubinTobata ward,and another (a press conference) at the Mitsui club in Moji-ko.

- Sorge: A Chronology,edited by Michael Yudell.

- Richard Sorge Stalin's Spy In Tokyo

- The Spy Who Saved The Soviets

- 1895 births

- 1944 deaths

- 20th-century executions by Japan

- Comintern people

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Communist Party of Germany politicians

- Executed Azerbaijani people

- Executed communists

- Executed German people

- Russian people executed abroad

- German communists

- German expatriates in China

- German expatriates in Japan

- 20th-century German journalists

- 20th-century German economists

- German male journalists

- German male writers

- German Marxists

- German people convicted of spying for the Soviet Union

- German people of Russian descent

- GRU officers

- Heroes of the Soviet Union

- Japan–Soviet Union relations

- Frankfurter Zeitung people

- People executed by Japan by hanging

- People from Baku Governorate

- People from the Weimar Republic

- Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Soviet people of German descent

- Soviet people of World War II

- Soviet spies

- People executed for spying for the Soviet Union

- University of Hamburg alumni

- World War II spies for the Soviet Union

- German Army personnel of World War I

- War scare

- Burials at Tama Cemetery