Haumea

Low-resolutionHubble Space Telescopeimage of Haumea and its two moons,Hi'iaka(top) andNamaka(bottom), June 2015 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | |

| Discovery date |

|

| Designations | |

| (136108) Haumea | |

| Pronunciation | /haʊˈmeɪ.ə,ˌhɑːuː-/[nb 1] |

Named after | Haumea |

| 2003 EL61 | |

| Adjectives | Haumean[7] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[8] | |

| Epoch17 December 2020 (JD2459200.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter2 | |

| Observation arc | 65 years and 291 days (24033 days) |

| Earliestprecoverydate | 22 March 1955 |

| Aphelion | 51.585AU(7.7170Tm) |

| Perihelion | 34.647 AU (5.1831 Tm) |

| 43.116 AU (6.4501 Tm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.19642 |

| 283.12yr(103,410 days)[9] | |

Averageorbital speed | 4.53 km/s[nb 2] |

| 218.205° | |

| 0° 0m12.533s/ day | |

| Inclination | 28.2137° |

| 122.167° | |

| ≈ 1 June 2133[10] ±2 days | |

| 239.041° | |

| Knownsatellites | 2(HiʻiakaandNamaka) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | |

| ≈8.14×106km2[nb 3][13] | |

| Volume | ≈1.98×109km3[nb 3][14] 0.0018Earths |

| Mass | (4.006±0.040)×1021kg[15] 0.00066Earths |

Meandensity | |

Equatorialsurface gravity | 0.93 m/s2at poles to 0.24 m/s2at longest axis |

Equatorialescape velocity | 1 km/s at poles to 0.71 km/s at longest axis |

| 3.915341±0.000005h[16] (0.163139208d) | |

| ≈ 126° (to orbit; assumed) 81.2° or 78.9° (toecliptic)[nb 6] | |

North poleright ascension | 282.6°±1.2°[17]: 3174 |

North poledeclination | −13.0°±1.3°or−11.8°±1.2°[17]: 3174 |

| Temperature | < 50K[20] |

| 17.3 (opposition)[23][24] | |

| 0.428±0.011(V-band) [16]·0.2 [9] | |

Haumea(minor-planet designation:136108 Haumea) is adwarf planetlocatedbeyondNeptune's orbit.[25]It was discovered in 2004 by a team headed byMike BrownofCaltechat thePalomar Observatory,and formally announced in 2005 by a team headed byJosé Luis Ortiz Morenoat theSierra Nevada ObservatoryinSpain,who had discovered it that year in precovery images taken by the team in 2003. From that announcement, it received the provisional designation 2003 EL61. On 17 September 2008, it was named afterHaumea,the Hawaiian goddess of childbirth, under the expectation by theInternational Astronomical Union(IAU) that it would prove to be a dwarf planet. Nominal estimates make it thethird-largest known trans-Neptunian object,afterErisandPluto,and approximately the size of Uranus's moonTitania.Precovery images of Haumea have been identified back to 22 March 1955.[9]

Haumea's mass is about one-third that of Pluto and 1/1400 that ofEarth.Although its shape has not been directly observed, calculations from itslight curveare consistent with it being aJacobi ellipsoid(the shape it would be if it were a dwarf planet), with its majoraxistwice as long as its minor. In October 2017, astronomers announced the discovery of aring systemaround Haumea, representing the first ring system discovered for atrans-Neptunian objectand a dwarf planet. Haumea's gravity was until recently thought to be sufficient for it to have relaxed intohydrostatic equilibrium,though that is now unclear. Haumea's elongated shape together with its rapidrotation,rings, and highalbedo(from a surface of crystalline water ice), are thought to be the consequences of agiant collision,which left Haumea the largest member of acollisional familythat includes several largetrans-Neptunian objectsand Haumea's two known moons,Hiʻiaka and Namaka.

History[edit]

Discovery[edit]

Two teams claim credit for the discovery of Haumea. A team consisting ofMike Brownof Caltech,David Rabinowitzof Yale University, andChad TrujilloofGemini Observatoryin Hawaii discovered Haumea on 28 December 2004, on images they had taken on 6 May 2004. On 20 July 2005, they published an online abstract of a report intended to announce the discovery at a conference in September 2005.[26]At around this time,José Luis Ortiz Morenoand his team at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía at Sierra Nevada Observatory in Spain found Haumea on images taken on 7-10 March 2003.[27]Ortiz emailed theMinor Planet Centerwith their discovery on the night of 27 July 2005.[27]

Brown initially conceded discovery credit to Ortiz,[28]but came to suspect the Spanish team of fraud upon learning that the Spanish observatory had accessed Brown's observation logs the day before the discovery announcement, a fact that they did not disclose in the announcement as would be customary. Those logs included enough information to allow the Ortiz team toprecoverHaumea in their 2003 images, and they were accessed again just before Ortiz scheduled telescope time to obtain confirmation images for a second announcement to the MPC on 29 July. Ortiz later admitted he had accessed the Caltech observation logs but denied any wrongdoing, stating he was merely verifying whether they had discovered a new object.[29]

IAU protocol is that discovery credit for aminor planetgoes to whoever first submits a report to the MPC (Minor Planet Center) with enough positional data for a decent determination of its orbit, and that the credited discoverer has priority in choosing a name. However, the IAU announcement on 17 September 2008, that Haumea had been named by a dual committee established for bodies expected to be dwarf planets, did not mention a discoverer. The location of discovery was listed as the Sierra Nevada Observatory of the Spanish team,[30][31]but the chosen name, Haumea, was the Caltech proposal. Ortiz's team had proposed "Ataecina",the ancient Iberian goddess of spring;[27]as achthonic deity,it would have been appropriate for aplutino,which Haumea was not.

Name and symbol[edit]

Until it was given a permanent name, the Caltech discovery team used the nickname "Santa"among themselves, because they had discovered Haumea on 28 December 2004, just after Christmas.[32]The Spanish team were the first to file a claim for discovery to theMinor Planet Center,in July 2005. On 29 July 2005, Haumea was given theprovisional designation2003 EL61,based on the date of the Spanish discovery image. On 7 September 2006, it was numbered and admitted into the official minor planet catalog as (136108) 2003 EL61.

Followingguidelinesestablished at the time by the IAU thatclassical Kuiper belt objectsbe given names of mythological beings associated with creation,[33]in September 2006 the Caltech team submitted formal names fromHawaiian mythologyto the IAU for both (136108) 2003 EL61and its moons, in order "to pay homage to the place where the satellites were discovered".[34]The names were proposed byDavid Rabinowitzof the Caltech team.[25]Haumeais the matron goddess of the island ofHawaiʻi,where theMauna Kea Observatoryis located. In addition, she is identified withPapa,the goddess of the earth and wife ofWākea(space),[35]which, at the time, seemed appropriate because Haumea was thought to be composed almost entirely of solid rock, without the thick ice mantle over a small rocky core typical of other known Kuiper belt objects.[36][37]Lastly, Haumea is the goddess of fertility and childbirth, with many children who sprang from different parts of her body;[35]this corresponds to the swarm of icy bodies thought to have broken off the main body during an ancient collision.[37]The two known moons, also believed to have formed in this manner,[37]are thus named after two of Haumea's daughters,HiʻiakaandNāmaka.[36]

The proposal by the Ortiz team, Ataecina, did not meet IAU naming requirements, because the names ofchthonicdeities were reserved for stablyresonant trans-Neptunian objectssuch asplutinosthat resonate 3:2 with Neptune, whereas Haumea was in an intermittent 7:12 resonance and so by some definitions was not a resonant body. The naming criteria would be clarified in late 2019, when the IAU decided that chthonic figures were to be used specifically for plutinos.(SeeAtaecina § Dwarf planet.)

Aplanetary symbolfor Haumea,⟨![]() ⟩,is included inUnicodeat U+1F77B.[38]Planetary symbols are no longer much used in astronomy, and 🝻 is mostly used by astrologers,[39]but has also been used by NASA.[40]The symbol was designed by Denis Moskowitz, a software engineer in Massachusetts; it combines and simplifies Hawaiian petroglyphs meaning 'woman' and 'childbirth'.[41]

⟩,is included inUnicodeat U+1F77B.[38]Planetary symbols are no longer much used in astronomy, and 🝻 is mostly used by astrologers,[39]but has also been used by NASA.[40]The symbol was designed by Denis Moskowitz, a software engineer in Massachusetts; it combines and simplifies Hawaiian petroglyphs meaning 'woman' and 'childbirth'.[41]

Orbit[edit]

Haumea has anorbital periodof 284 Earth years, aperihelionof 35AU,and anorbital inclinationof 28°.[9]It passedaphelionin early 1992, and is currently more than 50 AU from the Sun.[23]It will come to perihelion in 2133.[10]Haumea's orbit has a slightly greatereccentricitythan that of the other members ofits collisional family.This is thought to be due to Haumea's weak 7:12 orbital resonance with Neptune gradually modifying its initial orbit over the course of a billion years,[37][42]through theKozai effect,which allows the exchange of an orbit's inclination for increased eccentricity.[37][43][44]

With avisual magnitudeof 17.3,[23]Haumea is thethird-brightest objectin the Kuiper belt after Pluto andMakemake,and easily observable with a large amateur telescope.[45]However, because the planets and mostsmall Solar System bodiesshare acommon orbital alignmentfrom theirformationin theprimordial diskof the Solar System, most early surveys for distant objects focused on the projection on the sky of this common plane, called theecliptic.[46]As the region of sky close to the ecliptic became well explored, later sky surveys began looking for objects that had been dynamically excited into orbits with higher inclinations, as well as more distant objects, with slowermean motionsacross the sky.[47][48]These surveys eventually covered the location of Haumea, with its high orbital inclination and current position far from the ecliptic.

Possible resonance with Neptune[edit]

Haumea is thought to be in an intermittent 7:12orbital resonance with Neptune.[37]Itsascending nodeΩ precesses with a period of about 4.6 million years, and the resonance is broken twice per precession cycle, or every 2.3 million years, only to return a hundred thousand years or so later.[5]As this is not a simple resonance,Marc Buiequalifies it as non-resonant.[49]

Rotation[edit]

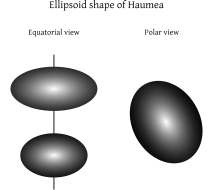

Haumea displays large fluctuations in brightness over a period of 3.9 hours, which can only be explained by a rotational period of this length.[50]This is faster than any other known equilibrium body in theSolar System,and indeed faster than any other known body larger than 100 km in diameter.[45]While most rotating bodies in equilibrium are flattened intooblate spheroids,Haumea rotates so quickly that it is distorted into a triaxialellipsoid.If Haumea were to rotate much more rapidly, it would distort itself into a dumbbell shape and split in two.[25]This rapid rotation is thought to have been caused by the impact that created its satellites and collisional family.[37]

The plane of Haumea'sequatoris oriented nearly edge-on from Earth at present and is also slightly offset to the orbital planes of itsringand its outermost moonHiʻiaka.Although initially assumed to be coplanar to Hiʻiaka's orbital plane by Ragozzine and Brown in 2009, their models of the collisional formation of Haumea's satellites consistently suggested Haumea's equatorial plane to be at least aligned with Hiʻiaka's orbital plane by approximately 1°.[15]This was supported with observations of astellar occultationby Haumea in 2017, which revealed the presence of a ring approximately coincident with the plane of Hiʻiaka's orbit and Haumea's equator.[12]A mathematical analysis of the occultation data by Kondratyev and Kornoukhov in 2018 placed constraints on the relative inclination angles of Haumea's equator to the orbital planes of its ring and Hiʻiaka, which were found to be inclined3.2°±1.4°and2.0°±1.0°relative to Haumea's equator, respectively.[17]

Physical characteristics[edit]

Size, shape, and composition[edit]

The size of a Solar System object can be deduced from itsoptical magnitude,its distance, and itsalbedo.Objects appear bright to Earth observers either because they are large or because they are highly reflective. If their reflectivity (albedo) can be ascertained, then a rough estimate can be made of their size. For most distant objects, the albedo is unknown, but Haumea is large and bright enough for itsthermal emissionto be measured, which has given an approximate value for its albedo and thus its size.[51]However, the calculation of its dimensions is complicated by its rapid rotation. Therotational physicsofdeformable bodiespredicts that over as little as a hundred days,[45]a body rotating as rapidly as Haumea will have been distorted into theequilibrium formof atriaxial ellipsoid.It is thought that most of the fluctuation in Haumea's brightness is caused not by local differences in albedo but by the alternation of the side view and ends view as seen from Earth.[45]

The rotation and amplitude of Haumea'slight curvewere argued to place strong constraints on its composition. If Haumea were inhydrostatic equilibriumand had a lowdensitylike Pluto, with a thick mantle oficeover a smallrockycore, its rapid rotation would have elongated it to a greater extent than the fluctuations in its brightness allow. Such considerations constrained its density to a range of 2.6–3.3 g/cm3.[52][45]By comparison, the Moon, which is rocky, has a density of 3.3 g/cm3,whereas Pluto, which is typical of icy objects in the Kuiper belt, has a density of 1.86 g/cm3.Haumea's possible high density covered the values forsilicate mineralssuch asolivineandpyroxene,which make up many of therocky objectsin the Solar System. This also suggested that the bulk of Haumea was rock covered with a relatively thin layer of ice. A thick ice mantle more typical of Kuiper belt objects may have been blasted off during the impact that formed the Haumean collisional family.[37]

Because Haumea has moons, the mass of the system can be calculated from their orbits usingKepler's third law.The result is4.2×1021kg,28% the mass of the Plutonian system and 6% that of theMoon.Nearly all of this mass is in Haumea.[15][53]

Several ellipsoid-model calculations of Haumea's dimensions have been made. The first model produced after Haumea's discovery was calculated fromground-basedobservations of Haumea'slight curveatopticalwavelengths: it provided a total length of 1,960 to 2,500 km and avisualalbedo(pv) greater than 0.6.[45]The most likely shape is a triaxial ellipsoid with approximate dimensions of 2,000 × 1,500 × 1,000 km, with an albedo of 0.71.[45]Observations by theSpitzer Space Telescopegave a diameter of1,150+250

−100kmand an albedo of0.84+0.1

−0.2,fromphotometryatinfraredwavelengths of 70 μm.[51]Subsequent light-curve analyses have suggested an equivalent circular diameter of 1,450 km.[54]In 2010 an analysis of measurements taken byHerschel Space Telescopetogether with the older Spitzer Telescope measurements yielded a new estimate of the equivalent diameter of Haumea—about 1300 km.[55]These independent size estimates overlap at an averagegeometric meandiameter of roughly 1,400 km. In 2013 the Herschel Space Telescope measured Haumea's equivalent circular diameter to be roughly1,240+69

−58km.[56]

However the observations of astellar occultationin January 2017 cast a doubt on all those conclusions. The measured shape of Haumea, while elongated as presumed before, appeared to have significantly larger dimensions – according to the data obtained from the occultation Haumea is approximately the diameter of Pluto along its longest axis and about half that at its poles.[12]The resulting density calculated from the observed shape of Haumea was about1.8 g/cm3– more in line with densities of other large TNOs. This resulting shape appeared to be inconsistent with a homogenous body in hydrostatic equilibrium,[12]though Haumea appears to be one of the largest trans-Neptunian objects discovered nonetheless,[51]smaller thanEris,Pluto,similar toMakemake,and possiblyGonggong,and larger thanSedna,Quaoar,andOrcus.

A 2019 study attempted to resolve the conflicting measurements of Haumea's shape and density usingnumerical modelingof Haumea as a differentiated body. It found that dimensions of ≈ 2,100 × 1,680 × 1,074 km (modeling the long axis at intervals of 25 km) were a best-fit match to the observed shape of Haumea during the 2017 occultation, while also being consistent with both surface and core scalene ellipsoid shapes in hydrostatic equilibrium.[11]The revised solution for Haumea's shape implies that it has a core of approximately 1,626 × 1,446 × 940 km, with a relatively high density of ≈2.68 g/cm3,indicative of a composition largely of hydrated silicates such askaolinite.The core is surrounded by an icy mantle that ranges in thickness from about 70 km at the poles to 170 km along its longest axis, comprising up to 17% of Haumea's mass. Haumea's mean density is estimated at ≈2.018 g/cm3,with an albedo of ≈ 0.66.[11]

Surface[edit]

In 2005, theGeminiandKecktelescopes obtainedspectraof Haumea which showed strong crystallinewater icefeatures similar to the surface of Pluto's moonCharon.[20]This is peculiar, because crystalline ice forms at temperatures above 110 K, whereas Haumea's surface temperature is below 50 K, a temperature at whichamorphous iceis formed.[20]In addition, the structure of crystalline ice is unstable under the constant rain ofcosmic raysand energetic particles from the Sun that strike trans-Neptunian objects.[20]The timescale for the crystalline ice to revert to amorphous ice under this bombardment is on the order of ten million years,[57]yet trans-Neptunian objects have been in their present cold-temperature locations for timescales of billions of years.[42]Radiation damage should also redden and darken the surface of trans-Neptunian objects where the common surface materials oforganicices andtholin-likecompounds are present, as is the case with Pluto. Therefore, the spectra andcoloursuggest Haumea and its family members have undergone recent resurfacing that produced fresh ice. However, no plausible resurfacing mechanism has been suggested.[22]

Haumea is as bright as snow, with an albedo in the range of 0.6–0.8, consistent with crystalline ice.[45]Other large TNOs such asErisappear to have albedos as high or higher.[58]Best-fit modeling of the surface spectra suggested that 66% to 80% of the Haumean surface appears to be pure crystalline water ice, with one contributor to the high albedo possiblyhydrogen cyanideorphyllosilicate clays.[20]Inorganic cyanide salts such as copper potassium cyanide may also be present.[20]

However, further studies of the visible and near infrared spectra suggest a homogeneous surface covered by an intimate 1:1 mixture of amorphous and crystalline ice, together with no more than 8% organics. The absence of ammonia hydrate excludescryovolcanismand the observations confirm that the collisional event must have happened more than 100 million years ago, in agreement with the dynamic studies.[59] The absence of measurablemethanein the spectra of Haumea is consistent with a warmcollisional historythat would have removed suchvolatiles,[20]in contrast toMakemake.[60]

In addition to the large fluctuations in Haumea's light curve due to the body's shape, which affect allcoloursequally, smaller independent colour variations seen in both visible and near-infrared wavelengths show a region on the surface that differs both in colour and in albedo.[61][62]More specifically, a large dark red area on Haumea's bright white surface was seen in September 2009, possibly an impact feature, which indicates an area rich in minerals and organic (carbon-rich) compounds, or possibly a higher proportion of crystalline ice.[50][63]Thus Haumea may have a mottled surface reminiscent of Pluto, if not as extreme.

Ring[edit]

A stellar occultation observed on 21 January 2017, and described in an October 2017Naturearticle indicated the presence of aringaround Haumea. This represents the first ring system discovered for a TNO.[12][64]The ring has a radius of about 2,287 km, a width of ~70 km and an opacity of 0.5. It is well within Haumea'sRoche limit,which would be at a radius of about 4,400 km if it were spherical (being nonspherical pushes the limit out farther).[12]The ring plane is inclined3.2°±1.4°with respect to Haumea's equatorial plane and approximately coincides with the orbital plane of its larger, outer moon Hiʻiaka.[12][65]The ring is also close to the 1:3orbit-spin resonancewith Haumea's rotation (which is at a radius of 2,285 ± 8 km from Haumea's center). The ring is estimated to contribute 5% to the total brightness of Haumea.[12]

In a study about thedynamicsof ring particles published in 2019, Othon Cabo Winter and colleagues have shown that the 1:3 resonance with Haumea's rotation isdynamically unstable,but that there is a stable region in thephase spaceconsistent with the location of Haumea's ring. This indicates that the ring particles originate on circular, periodic orbits that are close to, but not inside, the resonance.[66]

Satellites[edit]

Two smallsatelliteshave been discovered orbiting Haumea, (136108) Haumea IHiʻiakaand (136108) Haumea IINamaka.[30]Darin Ragozzine and Michael Brown discovered both in 2005, through observations of Haumea using theW. M. Keck Observatory.

Hiʻiaka, at first nicknamed "Rudolph"by the Caltech team,[67]was discovered 26 January 2005.[53]It is the outer and, at roughly 310 km in diameter, the larger and brighter of the two, and orbits Haumea in a nearly circular path every 49 days.[68]Strong absorption features at 1.5 and 2micrometresin theinfraredspectrum are consistent with nearly pure crystalline water ice covering much of the surface.[69]The unusual spectrum, along with similar absorption lines on Haumea, led Brown and colleagues to conclude that capture was an unlikely model for the system's formation, and that the Haumean moons must be fragments of Haumea itself.[42]

Namaka, the smaller, inner satellite of Haumea, was discovered on 30 June 2005,[70]and nicknamed "Blitzen".It is a tenth the mass of Hiʻiaka, orbits Haumea in 18 days in a highly elliptical,non-Keplerianorbit, and as of 2008[update]is inclined 13° from the larger moon, whichperturbsits orbit.[71] The relatively large eccentricities together with the mutual inclination of the orbits of the satellites are unexpected as they should have been damped by thetidal effects.A relatively recent passage by a 3:1 resonance with Hiʻiaka might explain the current excited orbits of the Haumean moons.[72]

At present, the orbits of the Haumean moons appear almost exactly edge-on from Earth, with Namaka periodicallyoccultingHaumea.[73]Observation of such transits would provide precise information on the size and shape of Haumea and its moons,[74]as happened inthe late 1980s with Pluto and Charon.[75]The tiny change in brightness of the system during these occultations will require at least amedium-apertureprofessional telescopefor detection.[74][76]Hiʻiaka last occulted Haumea in 1999, a few years before discovery, and will not do so again for some 130 years.[77]However, in a situation unique amongregular satellites,Namaka's orbit is being greatlytorquedby Hiʻiaka, which preserved the viewing angle of Namaka–Haumea transits for several more years.[71][74][76]

| Name | Diameter (km)[78][79] | Semi-major axis (km)[80] | Mass (kg)[80] | Discovery date[78][81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haumea | 2 322 × 1,704 × 1,026 | (4.006 ± 0.040) × 1021 | 7 March 2003[81] | |

| Hiʻiaka | ≈ 310 | 49 880 | (1.79 ± 0.11) x 1019 | 26 January 2005 |

| Namaka | ≈ 170 | 25 657 | (1.79 ± 1.48) x 1018 | 30 June 2005 |

Collisional family[edit]

Haumea is the largest member of itscollisional family,a group of astronomical objects with similar physical and orbital characteristics thought to have formed when a larger progenitor was shattered by an impact.[37]This family is the first to be identified among TNOs and includes—beside Haumea and its moons—(55636) 2002 TX300(≈364 km),(24835) 1995 SM55(≈174 km),(19308) 1996 TO66(≈200 km),(120178) 2003 OP32(≈230 km), and(145453) 2005 RR43(≈252 km).[6]Brown and colleagues proposed that the family were a direct product of the impact that removed Haumea's ice mantle,[37]but a second proposal suggests a more complicated origin: that the material ejected in the initial collision instead coalesced into a large moon of Haumea, which was later shattered in a second collision, dispersing its shards outwards.[82]This second scenario appears to produce a dispersion of velocities for the fragments that is more closely matched to the measured velocity dispersion of the family members.[82]

The presence of the collisional family could imply that Haumea and its "offspring" might have originated in thescattered disc.In today's sparsely populated Kuiper belt, the chance of such a collision occurring over the age of the Solar System is less than 0.1 percent.[83]The family could not have formed in the denser primordial Kuiper belt because such a close-knit group would have been disrupted byNeptune's migrationinto the belt—the believed cause of the belt's current low density.[83]Therefore, it appears likely that the dynamic scattered disc region, in which the possibility of such a collision is far higher, is the place of origin for the object that generated Haumea and its kin.[83]

Because it would have taken at least a billion years for the group to have diffused as far as it has, the collision which created the Haumea family is believed to have occurred very early in the Solar System's history.[6]

Exploration[edit]

Haumea was observed from afar by theNew Horizonsspacecraft in October 2007, January 2017, and May 2020, from distances of 49 AU, 59 AU, and 63 AU, respectively.[19]The spacecraft's outbound trajectory permitted observations of Haumea at highphase anglesthat are otherwise unobtainable from Earth, enabling the determination of the light scattering properties andphase curvebehavior of Haumea's surface.[19]

Joel Poncy and colleagues calculated that a flyby mission to Haumea could take 14.25 years using a gravity assist from Jupiter, based on a launch date of 25 September 2025. Haumea would be 48.18 AU from the Sun when the spacecraft arrives. A flight time of 16.45 years can be achieved with launch dates on 1 November 2026, 23 September 2037, and 29 October 2038.[84] Haumea could become a target for an exploration mission,[85]and an example of this work is a preliminary study on a probe to Haumea and its moons (at 35–51 AU).[86]Probe mass, power source, and propulsion systems are key technology areas for this type of mission.[85]

See also[edit]

- Astronomical naming conventions

- Clearing the neighbourhood

- International Astronomical Union

- Planets beyond Neptune

- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun

Notes[edit]

- ^how-MAY-ə,with three syllables according to the English pronunciation in Hawaii,[1]orHAH-oo-MAY-əwith four syllables according to Brown's students.[2][3]

- ^Assuming acircular orbitwith negligible eccentricity, the meanorbital speedcan be approximated by the timeTit takes to complete one revolution around its orbitalcircumference,with the radius being itssemi-major axisa:.

- ^abcdefBest fit physical model assuminghydrostatic equilibriumfor Haumea.[11]

- ^Occultation-derived model based on the assumption Haumea's ring does not contribute to its total brightness.[12]

- ^abOccultation-derived model based on the upper-limit assumption that Haumea's ring contributes 5% to its total brightness.[12]

- ^Kondratyev and Kornoukhov (2018) give Haumea's north pole orientation in terms ofequatorial coordinates,whereαisright ascensionandδisdeclination.[17]: 3174 Transformingequatorial coordinates toecliptic coordinatesgivesλ≈ 282.5° andβ≈ 9.9° for the first solution of (α,δ) = (282.6°, –13.0°), orλ≈ 282.6° andβ≈ 11.1° for the second solution of (α,δ) = (282.6°, –11.8°).[18]Theecliptic latitude,β,is the angular offset from theecliptic plane,whereasinclinationiwith respect to the ecliptic is the angular offset from theecliptic north poleatβ= +90°;iwith respect to the ecliptic would be thecomplementofβ,which is expressed by the differencei= 90° –β.Thus, Haumea's axial tilt is 81.2° or 78.9° with respect to the ecliptic, for the first and secondβvalues, respectively.

References[edit]

- ^New dwarf planet named for Hawaiian goddessArchived2015-12-08 at theWayback Machine(HeraldNet, 19 September 2008)

- ^"DPS08 Webstreaming".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-01-06.Retrieved2009-02-14.

- ^"365 Days of Astronomy".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-02-20.Retrieved2009-04-11.

- ^"MPEC 2010-H75: Distant Minor Planets (2010 May 14.0 TT)".Minor Planet Center. 2010-04-10.Archivedfrom the original on 2014-07-16.Retrieved2010-07-02.

- ^ab Marc W. Buie(2008-06-25)."Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 136108".Southwest Research Institute (Space Science Department).Archivedfrom the original on 2011-05-18.Retrieved2008-10-02.

- ^abc Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M. E. (2007). "Candidate Members and Age Estimate of the Family of Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61".Astronomical Journal.134(6): 2160–2167.arXiv:0709.0328.Bibcode:2007AJ....134.2160R.doi:10.1086/522334.S2CID8387493.

- ^E.g. Giovanni Vulpetti (2013)Fast Solar Sailing,p. 333.

- ^"(136108) Haumea = 2003 EL61".Minor Planet Center.International Astronomical Union.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2021.Retrieved14 March2021.

- ^abcd"Jet Propulsion Laboratory Small-Body Database Browser: 136108 Haumea (2003 EL61) "(2019-08-26 last obs). NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-11.Retrieved2020-02-20.

- ^ab"Horizons Batch for Haumea at perihelion around 1 June 2133".JPL Horizons(Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive. The JPL SBDB generically (incorrectly) lists an unperturbed two-body perihelion date in 2132). Jet Propulsion Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-09-13.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^abcd Dunham, E. T.; Desch, S. J.; Probst, L. (April 2019)."Haumea's Shape, Composition, and Internal Structure".The Astrophysical Journal.877(1): 11.arXiv:1904.00522.Bibcode:2019ApJ...877...41D.doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab13b3.S2CID90262114.

- ^abcdefghijkOrtiz, J. L.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Sicardy, B.; Benedetti-Rossi, G.; Bérard, D.; Morales, N.; et al. (2017)."The size, shape, density and ring of the dwarf planet Haumea from a stellar occultation"(PDF).Nature.550(7675): 219–223.arXiv:2006.03113.Bibcode:2017Natur.550..219O.doi:10.1038/nature24051.hdl:10045/70230.PMID29022593.S2CID205260767.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2020-11-07.Retrieved2020-08-19.

- ^"Ellipsoid surface area: 8.13712×10^6 km2".wolfram Alpha.20 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2020.Retrieved20 December2019.

- ^"Ellipsoid volume: 1.98395×10^9 km3".wolfram Alpha.20 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2020.Retrieved20 December2019.

- ^abc Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M. E. (2009). "Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea = 2003 EL61".The Astronomical Journal.137(6): 4766–4776.arXiv:0903.4213.Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4766R.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766.S2CID15310444.

- ^abSantos-Sanz, P.; Lellouch, E.; Groussin, O.; Lacerda, P.; Muller, T. G.; Ortiz, J. L.; Kiss, C.; Vilenius, E.; Stansberry, J.; Duffard, R.; Fornasier, S.; Jorda, L.; Thirouin, A. (August 2017). ""TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region XII. Thermal light curves of Haumea,2003 VS2and2003 AZ84with Herschel/PACS ".Astronomy & Astrophysics.604(A95): 19.arXiv:1705.09117.Bibcode:2017A&A...604A..95S.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201630354.S2CID119489622.

- ^abcd Kondratyev, B. P.; Kornoukhov, V. S. (August 2018). "Determination of the body of the dwarf planet Haumea from observations of a stellar occultation and photometry data".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.478(3): 3159–3176.Bibcode:2018MNRAS.478.3159K.doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1321.

- ^"Coordinate Transformation & Galactic Extinction Calculator".NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database.California Institute of Technology.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2023.Retrieved11 February2023.Equatorial → Ecliptic, J2000 for equinox and epoch. NOTE: When inputting equatorial coordinates, specify the units in the format "282.6d" instead of "282.6".

- ^abcVerbiscer, Anne J.; Helfenstein, Paul; Porter, Simon B.; Benecchi, Susan D.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Lauer, Tod R.; et al. (April 2022)."The Diverse Shapes of Dwarf Planet and Large KBO Phase Curves Observed from New Horizons".The Planetary Science Journal.3(4): 31.Bibcode:2022PSJ.....3...95V.doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac63a6.95.

- ^abcdefg Chadwick A. Trujillo;Michael E. Brown;Kristina Barkume; Emily Shaller;David L. Rabinowitz(2007). "The Surface of 2003 EL61in the Near Infrared ".Astrophysical Journal.655(2): 1172–1178.arXiv:astro-ph/0601618.Bibcode:2007ApJ...655.1172T.doi:10.1086/509861.S2CID118938812.

- ^ Snodgrass, C.; Carry, B.; Dumas, C.; Hainaut, O. (February 2010). "Characterisation of candidate members of (136108) Haumea's family".Astronomy and Astrophysics.511:A72.arXiv:0912.3171.Bibcode:2010A&A...511A..72S.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913031.S2CID62880843.

- ^ab Rabinowitz, D. L.; Schaefer, Bradley E.; Schaefer, Martha; Tourtellotte, Suzanne W. (2008). "The Youthful Appearance of the 2003 EL61Collisional Family ".The Astronomical Journal.136(4): 1502–1509.arXiv:0804.2864.Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1502R.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/4/1502.S2CID117167835.

- ^abc "AstDys (136108) Haumea Ephemerides".Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-06-29.Retrieved2009-03-19.

- ^"HORIZONS Web-Interface".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Solar System Dynamics.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-07-18.Retrieved2008-07-02.

- ^abc"IAU names fifth dwarf planet Haumea".IAU Press Release. 2008-09-17. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-02.Retrieved2008-09-17.

- ^ Michael E Brown."The electronic trail of the discovery of 2003 EL61".Caltech.Archivedfrom the original on 2006-09-01.Retrieved2006-08-16.

- ^abc Pablo Santos Sanz (2008-09-26)."La historia de Ataecina vs Haumea"(in Spanish). infoastro.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-09-29.Retrieved2008-09-29.

- ^Michael E. Brown.How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming,chapter 9: "The Tenth Planet"

- ^ Jeff Hecht (2005-09-21)."Astronomer denies improper use of web data".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-03-13.Retrieved2009-01-12.

- ^ab "Dwarf Planets and their Systems".US Geological Survey Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-06-29.Retrieved2008-09-17.

- ^ Rachel Courtland (2008-09-19)."Controversial dwarf planet finally named 'Haumea'".NewScientistSpace.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-09-19.Retrieved2008-09-19.

- ^

"Santa et al".NASA Astrobiology Magazine. 2005-09-10. Archived from the original on 2006-04-26.Retrieved2008-10-16.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Naming of Astronomical Objects: Minor planets".International Astronomical Union.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-12-16.Retrieved2008-11-17.

- ^ Mike Brown (2008-09-17)."Dwarf planets: Haumea".Caltech.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-09-15.Retrieved2008-09-18.

- ^abRobert D. Craig (2004).Handbook of Polynesian Mythology.ABC-CLIO. p. 128.ISBN978-1-57607-894-5.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-08.Retrieved2020-11-11.

- ^ab "News Release – IAU0807: IAU names fifth dwarf planet Haumea".International Astronomical Union.2008-09-17.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-07-08.Retrieved2008-09-18.

- ^abcdefghijBrown, M. E.; Barkume, K. M.; Ragozzine, D.; Schaller, L. (2007)."A collisional family of icy objects in the Kuiper belt"(PDF).Nature.446(7133): 294–296.Bibcode:2007Natur.446..294B.doi:10.1038/nature05619.PMID17361177.S2CID4430027.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2020-05-04.Retrieved2019-07-14.

- ^"Proposed New Characters: The Pipeline".Archivedfrom the original on 2022-01-29.Retrieved2022-01-29.

- ^Miller, Kirk (26 October 2021)."Unicode request for dwarf-planet symbols"(PDF).unicode.org.Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 March 2022.Retrieved6 August2022.

- ^JPL/NASA (22 April 2015)."What is a Dwarf Planet?".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-01-19.Retrieved2021-09-24.

- ^Anderson, Deborah (4 May 2022)."Out of this World: New Astronomy Symbols Approved for the Unicode Standard".unicode.org.The Unicode Consortium.Archivedfrom the original on 6 August 2022.Retrieved6 August2022.

- ^abc Michael E. Brown."The largest Kuiper belt objects"(PDF).Caltech.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2008-10-01.Retrieved2008-09-19.

- ^Nesvorný, D; Roig, F. (2001). "Mean Motion Resonances in the Transneptunian Region Part II: The 1: 2, 3: 4, and Weaker Resonances".Icarus.150(1): 104–123.Bibcode:2001Icar..150..104N.doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6568.S2CID15167447.

- ^ Kuchner, Marc J.; Brown, Michael E.; Holman, Matthew (2002). "Long-Term Dynamics and the Orbital Inclinations of the Classical Kuiper Belt Objects".The Astronomical Journal.124(2): 1221–1230.arXiv:astro-ph/0206260.Bibcode:2002AJ....124.1221K.doi:10.1086/341643.S2CID12641453.

- ^abcdefgh Rabinowitz, D. L.; Barkume, Kristina; Brown, Michael E.; Roe, Henry; Schwartz, Michael; Tourtellotte, Suzanne; Trujillo, Chad (2006). "Photometric Observations Constraining the Size, Shape, and Albedo of 2003 EL61,a Rapidly Rotating, Pluto-Sized Object in the Kuiper Belt ".Astrophysical Journal.639(2): 1238–1251.arXiv:astro-ph/0509401.Bibcode:2006ApJ...639.1238R.doi:10.1086/499575.S2CID11484750.

- ^ C. A. Trujillo & M. E. Brown (June 2003). "The Caltech Wide Area Sky Survey".Earth, Moon, and Planets.112(1–4): 92–99.Bibcode:2003EM&P...92...99T.doi:10.1023/B:MOON.0000031929.19729.a1.S2CID189905639.

- ^ Brown, M. E.; Trujillo, C.; Rabinowitz, D. L. (2004). "Discovery of a candidate inner Oort cloud planetoid".The Astrophysical Journal.617(1): 645–649.arXiv:astro-ph/0404456.Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B.doi:10.1086/422095.S2CID7738201.

- ^ Schwamb, M. E.; Brown, M. E.; Rabinowitz, D. L. (2008). "Constraints on the distant population in the region of Sedna".American Astronomical Society, DPS Meeting #40, #38.07.40:465.Bibcode:2008DPS....40.3807S.

- ^"Orbit and Astrometry for 136108".boulder.swri.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-13.Retrieved2020-07-14.

- ^ab Agence France-Presse (2009-09-16)."Astronomers get lock on diamond-shaped Haumea".European Planetary Science Congress in Potsdam.News Limited. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-09-23.Retrieved2009-09-16.

- ^abc Stansberry, J.; Grundy, W.; Brown, M.; Cruikshank, D.; Spencer, J.; Trilling, D.; Margot, J-L. (2008). "Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from Spitzer Space Telescope".The Solar System Beyond Neptune.University of Arizona Press: 161.arXiv:astro-ph/0702538.Bibcode:2008ssbn.book..161S.

- ^ Alexandra C. Lockwood; Michael E. Brown; John Stansberry (2014). "The size and shape of the oblong dwarf planet Haumea".Earth, Moon, and Planets.111(3–4): 127–137.arXiv:1402.4456v1.Bibcode:2014EM&P..111..127L.doi:10.1007/s11038-014-9430-1.S2CID18646829.

- ^abBrown, M. E.; Bouchez, A. H.; Rabinowitz, D.; Sari, R.; Trujillo, C. A.; Van Dam, M.; Campbell, R.; Chin, J.; Hartman, S.; Johansson, E.; Lafon, R.; Le Mignant, D.; Stomski, P.; Summers, D.; Wizinowich, P. (2005)."Keck Observatory Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics Discovery and Characterization of a Satellite to the Large Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61"(PDF).Astrophysical Journal Letters.632(1): L45–L48.Bibcode:2005ApJ...632L..45B.doi:10.1086/497641.S2CID119408563.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2017-12-02.Retrieved2018-11-04.

- ^ Lacerda, P.; Jewitt, D. C. (2007). "Densities of Solar System Objects from Their Rotational Light Curves".Astronomical Journal.133(4): 1393–1408.arXiv:astro-ph/0612237.Bibcode:2007AJ....133.1393L.doi:10.1086/511772.S2CID17735600.

- ^ Lellouch, E.; Kiss, C.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Müller, T. G.; Fornasier, S.; Groussin, O.; et al. (2010). ""TNOs are cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region II. The thermal lightcurve of (136108) Haumea ".Astronomy and Astrophysics.518:L147.arXiv:1006.0095.Bibcode:2010A&A...518L.147L.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014648.S2CID119223894.

- ^ Fornasier, S.; Lellouch, E.; Müller, T.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Panuzzo, P.; Kiss, C.; Lim, T.; Mommert, M.;Bockelée-Morvan, D.;Vilenius, E.; Stansberry, J.; Tozzi, G. P.; Mottola, S.; Delsanti, A.; Crovisier, J.; Duffard, R.; Henry, F.; Lacerda, P.; Barucci, A.; Gicquel, A. (2013).""TNOs are cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region VIII. Combined Herschel PACS and SPIRE observations of nine bright targets at 70–500 μm "(PDF).Astronomy and Astrophysics.555:A15.arXiv:1305.0449.Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..15F.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321329.S2CID119261700.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2014-12-05.

- ^ "Charon: An ice machine in the ultimate deep freeze"(Press release).Gemini Observatory.17 July 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2011.Retrieved2007-07-18.

- ^ Brown, M. E.; Schaller, E. L.; Roe, H. G.; Rabinowitz, D. L.; Trujillo, C. A. (2006)."Direct measurement of the size of 2003 UB313 from the Hubble Space Telescope"(PDF).The Astrophysical Journal Letters.643(2): L61–L63.arXiv:astro-ph/0604245.Bibcode:2006ApJ...643L..61B.doi:10.1086/504843.S2CID16487075.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2008-09-10.

- ^ Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Brunetto, R.; Licandro, J.; Gil-Hutton, R.; Roush, T. L.; Strazzulla, G. (2009). "Study of the Surface of 2003 EL61, the largest carbon-depleted object in the trans-neptunian belt".Astronomy and Astrophysics.496(2): 547–556.arXiv:0803.1080.Bibcode:2009A&A...496..547P.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200809733.S2CID15139257.

- ^ Tegler, S. C.; Grundy, W. M.; Romanishin, W.; Consolmagno, G. J.; Mogren, K.; Vilas, F. (2007). "Optical Spectroscopy of the Large Kuiper Belt Objects 136472 (2005 FY9) and 136108 (2003 EL61) ".The Astronomical Journal.133(2): 526–530.arXiv:astro-ph/0611135.Bibcode:2007AJ....133..526T.doi:10.1086/510134.S2CID10673951.

- ^ P. Lacerda; D. Jewitt & N. Peixinho (2008). "High-Precision Photometry of Extreme KBO 2003 EL61".Astronomical Journal.135(5): 1749–1756.arXiv:0801.4124.Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1749L.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/5/1749.S2CID115712870.

- ^ P. Lacerda (2009). "Time-Resolved Near-Infrared Photometry of Extreme Kuiper Belt Object Haumea".Astronomical Journal.137(2): 3404–3413.arXiv:0811.3732.Bibcode:2009AJ....137.3404L.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/2/3404.S2CID15210854.

- ^ "Strange Dwarf Planet Has Red Spot".Space.15 September 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2009.Retrieved2009-11-12.

- ^Surprise! Dwarf Planet Haumea Has a RingArchived2017-10-22 at theWayback Machine,Sky and Telescope, 13 October 2017.

- ^ Kondratyev, B. P.; Kornoukhov, V. S. (October 2020). "Secular Evolution of Rings around Rotating Triaxial Gravitating Bodies".Astronomy Reports.64(10): 870–875.Bibcode:2020ARep...64..870K.doi:10.1134/S1063772920100030.

- ^Winter, O. C.; Borderes-Motta, G.; Ribeiro, T. (2019). "On the location of the ring around the dwarf planet Haumea".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.484(3): 3765–3771.arXiv:1902.03363.doi:10.1093/mnras/stz246.S2CID119260748.

- ^ K. Chang (20 March 2007)."Piecing Together the Clues of an Old Collision, Iceball by Iceball".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2014.Retrieved2008-10-12.

- ^ Brown, M. E.;Van Dam, M. A.; Bouchez, A. H.; Le Mignant, D.; Campbell, R. D.; Chin, J. C. Y.; Conrad, A.; Hartman, S. K.; Johansson, E. M.; Lafon, R. E.; Rabinowitz, D. L. Rabinowitz; Stomski, P. J. Jr.; Summers, D. M.; Trujillo, C. A.; Wizinowich, P. L. (2006)."Satellites of the Largest Kuiper Belt Objects"(PDF).The Astrophysical Journal.639(1): L43–L46.arXiv:astro-ph/0510029.Bibcode:2006ApJ...639L..43B.doi:10.1086/501524.S2CID2578831.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-11-03.Retrieved2011-10-19.

- ^ K. M. Barkume; M. E. Brown & E. L. Schaller (2006). "Water Ice on the Satellite of Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61".Astrophysical Journal Letters.640(1): L87–L89.arXiv:astro-ph/0601534.Bibcode:2006ApJ...640L..87B.doi:10.1086/503159.S2CID17831967.

- ^ Green, Daniel W. E. (1 December 2005)."Iauc 8636".Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2018.

- ^ab Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M. E.; Trujillo, C. A.; Schaller, E. L. (2008).Orbits and Masses of the 2003 EL61 Satellite System.AAS DPS conference 2008.Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.Vol. 40. p. 462.Bibcode:2008DPS....40.3607R.

- ^ Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M. E. (2009). "Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea = 2003 EL61".The Astronomical Journal.137(6): 4766–4776.arXiv:0903.4213.Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4766R.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766.S2CID15310444.

- ^ "IAU Circular 8949".International Astronomical Union.17 September 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 11 January 2009.Retrieved2008-12-06.

- ^abc "Mutual events of Haumea and Namaka".Archivedfrom the original on 2009-02-24.Retrieved2009-02-18.

- ^ L.-A. A. McFadden; P. R. Weissman; T. V. Johnson (2007).Encyclopedia of the Solar System.Academic Press.ISBN978-0-12-088589-3.

- ^ab Fabrycky, D. C.; Holman, M. J.; Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M. E.; Lister, T. A.; Terndrup, D. M.; Djordjevic, J.; Young, E. F.; Young, L. A.; Howell, R. R. (2008).Mutual Events of 2003 EL61and its Inner Satellite.AAS DPS conference 2008.Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.Vol. 40. p. 462.Bibcode:2008DPS....40.3608F.

- ^ M. Brown (18 May 2008)."Moon shadow Monday (fixed)".Mike Brown's Planets.Archivedfrom the original on 1 October 2008.Retrieved2008-09-27.

- ^ab"Moons of the Dwarf Planet Haumea: Hi'iaka and Namaka - Windows to The Universe".Windows To The Universe.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-28.Retrieved2021-06-08.

- ^Ortiz, J. L.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Sicardy, B.; Benedetti-Rossi, G.; Bérard, D.; Morales, N.; Duffard, R.; Braga-Ribas, F.; Hopp, U.; Ries, C.; Nascimbeni, V. (October 2017)."The size, shape, density and ring of the dwarf planet Haumea from a stellar occultation".Nature.550(7675): 219–223.arXiv:2006.03113.Bibcode:2017Natur.550..219O.doi:10.1038/nature24051.ISSN0028-0836.PMID29022593.S2CID205260767.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-06-23.Retrieved2021-07-08.

- ^abRagozzine, D.; Brown, M. E. (2009-06-01)."Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea (2003 El61)".The Astronomical Journal.137(6): 4766–4776.arXiv:0903.4213.Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4766R.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766.ISSN0004-6256.S2CID15310444.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-09.Retrieved2021-07-08.

- ^ab"In Depth | Haumea".NASA Solar System Exploration.Archivedfrom the original on June 29, 2021.RetrievedJuly 8,2021.

- ^ab Schlichting, H. E.; Sari, R. (2009). "The Creation of Haumea's Collisional Family".The Astrophysical Journal.700(2): 1242–1246.arXiv:0906.3893.Bibcode:2009ApJ...700.1242S.doi:10.1088/0004-637X/700/2/1242.S2CID19022987.

- ^abc Levison, H. F.; Morbidelli, A.; Vokrouhlický, D.; Bottke, W. F. (2008). "On a Scattered Disc Origin for the 2003 EL61Collisional Family—an Example of the Importance of Collisions in the Dynamics of Small Bodies ".Astronomical Journal.136(3): 1079–1088.arXiv:0809.0553.Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1079L.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/3/1079.S2CID10861444.

- ^McGranaghan, R.; Sagan, B.; Dove, G.; Tullos, A.; Lyne, J. E.; Emery, J. P. (2011). "A Survey of Mission Opportunities to Trans-Neptunian Objects".Journal of the British Interplanetary Society.64:296–303.Bibcode:2011JBIS...64..296M.

- ^abPoncy, Joel; Fontdecaba Baiga, Jordi; Feresinb, Fred; Martinota, Vincent (2011). "A preliminary assessment of an orbiter in the Haumean system: How quickly can a planetary orbiter reach such a distant target?".Acta Astronautica.68(5–6): 622–628.Bibcode:2011AcAau..68..622P.doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2010.04.011.

- ^Paul Gilster:Fast Orbiter to HaumeaArchived2015-09-23 at theWayback Machine.Centauri Dreams—The News of the Tau Zero Foundation. 14 July 2009, retrieved 15 January 2011

External links[edit]

- (136108) Haumea, Hiʻiaka, and Namakaat Johnston's Archive (updated 21 September 2014)

- International Year of Astronomy 2009podcast: Dwarf Planet Haumea (Darin Ragozzine)

- Haumea as seen on June 10, 2011by Mike Brown using the 4.20 m (165 in)WHT/~0:30–3:30 dip in the brightness of Haumea+Namaka comes when Namaka crosses Haumea(Hiʻiaka, the outer moon, is blended in the images, but it rotates every 4.5 hr and adds a little variation)

- Animation of Haumea's intermittent 7:12 resonance with Neptune over the next 3.5 million years

- Solar System

- Minor planet object articles (numbered)

- Haumea (dwarf planet)

- Haumea family

- Trans-Neptunian objects

- Discoveries by Michael E. Brown

- Discoveries by Chad Trujillo

- Discoveries by David L. Rabinowitz

- Named minor planets

- Planetary rings

- Objects observed by stellar occultation

- Astronomical objects discovered in 2004

- Dwarf planets