Romanticism and economics

Severaleconomictheories of the first half of the 19th century were influenced byRomanticism,most notably those developed byAdam Müller,Simonde de Sismondi,Johann Gottlieb FichteandThomas Carlyle.Michael Löwyand Robert Sayre first formulated their thesis about Romanticism as ananti-capitalistandanti-modernistworldviewin a 1984 article called "Figures of Romantic Anti-capitalism".[1]Romantic anti-capitalism was a wide spectrum of opposition tocapitalism,ultimately tracing its roots back to the Romantic movement of the early 19th century, but acquiring a new impetus in the latter part of the 19th century.[1]

Vladimir Leninhad written already in 1897 that "the wishes of the romanticists are very good (as are those of theNarodniks). Their recognition of the contradictions of capitalism places them above the blind optimists who deny the existence of these contradictions. "[2]

Karl Marxin 1868 also considered Romanticism to have been the first historical trend of opposition to capitalism, to be followed by the trend ofsocialism:"The first reaction against theFrench Revolutionand theperiod of Enlightenmentbound up with it was naturally to see everything as mediaeval and Romantic, even people likeGrimmare not free from this. The second reaction is to look beyond the Middle Ages into theprimitiveage of each nation, and that corresponds to the socialist tendency, although these learned men have no idea that the two have any connection. "[3][4]

Considering Romanticism as a reflection of the age beginning after theFrench Revolutionand its inherent social contradictions, Marx andEngelsdistinguished between "revolutionary Romanticism", which rejected capitalism and was striving towards the future, and Romantic criticism of capitalism from the point of view of the past. They also differentiated between the Romantic writers who idealized thefeudalsocial system: they valued those whose works concealeddemocraticand critical elements under a veneer ofreactionaryutopias,and criticized the "reactionary Romantics", whose sympathies for the past amounted to a defense of the interests of thenobility.Marx and Engels were especially fond of the works of such revolutionary romantics asByronandShelley.[5]

Johann Gottlieb Fichte[edit]

GermanidealistphilosopherJohann Gottlieb Fichte's 1800 economic treatiseThe Closed Commercial Statehad a profound influence on the economic theories of German Romanticism. In it, Fichte argues the need for the strictest, purely guild-like regulation of industry.

The "exemplary rational state" (Vernunftstaat), Fichte argues, should not allow any of its "subjects" to engage in this or that production, failing to pass the preliminary test, not certifying government agents in their professional skills and agility.[6]According to Vladimir Mikhailovich Shulyatikov, "this kind of demand was typical ofMittelstand,the German pettymiddle class,the class ofartisans,hoping by creating artificial barriers to stop the victorious march of big capital and thus save themselves from inevitable death. The same demand was imposed on the state, as is evident from Fichte's treatise, by the German "factory" (Fabrik), more precisely, the manufacture of the early 19th century ".[7]

Fichte opposedfree tradeand unrestrained capitalist industrial growth, stating: "There is an endless war of all against all... And this war is becoming more fierce, unjust, more dangerous in its consequences, the more the world's population grows, the more acquisitions the trading state makes, the more production and art (industry) develops and, together with thus, the number of circulating goods increases, and with them the needs become more and more diversified. What, with the simple way of life of nations, was done before without great injustices and oppression, turns, thanks to increased needs, into flagrant injustice, into a source of great evils. The buyer tries to take the goods away from the seller; therefore he demands freedom of trade, i.e. freedom for the seller to wander around the markets, freedom not to find a sale for goods and sell them significantly below their value. Therefore, he requires strong competition between manufacturers (Fabrikanten) and merchants. "[6]

The only means that could save the modern world, which would destroy evil at the root, is, according to Fichte, to split the "world state" (theglobal market) into separate self-sufficient bodies. Each such body, each "closed trading state" will be able to regulate its internal economic relations. It will be able to both extract and process everything that is needed to meet the needs of its citizens. It will carry out the ideal organization of production.[7]Fichte argued for government regulation of industrial growth, writing "Only by limitation does a certain industry become the property of the class that deals with it".[6]

Vladimir Mikhailovich Shulyatikov considers the economics of German idealists and Romantics as representing the compromise of the Germanbourgeoisieof the early 19th century with the monarchical State:

The Frenchphysiocratsproclaimed the principle: "Laissez faire!"On the other hand, the German capitalists of the 1800s, whose ideologists were theobjective idealists,professed a belief in the saving effect of government tutelage.[7]

Adam Müller[edit]

Adam Müllerwas the first intellectual from within the ranks of the German Romantic movement to publish comprehensive studies on economics and the state, influenced by Fichte. Müller was aconservativewriter whose vision of the state was one of an absolute power, in contrast to theorists who emphasized therights of mansuch asMontesquieuandRousseau.[8]

His position inpolitical economyis defined by his strong opposition toAdam Smith's system of materialistic-liberal(so-calledclassical) political economy, or the so-called industry system. He censures Smith as presenting a one-sidedly material and individualistic conception of society, and as being too exclusively English in his views. Müller is thus also an adversary offree trade.In contrast with the economicalindividualismof Adam Smith, he emphasizes the ethical element in national economy, the duty of the state toward the individual, and the religious basis which is also necessary in this field. Müller's importance in the history of political economy is acknowledged even by the opponents of his religious and political point of view. His reaction against Adam Smith, saysRoscher(Geschichte der National-Ökonomik,p. 763), "is not blind or hostile, but is important, and often truly helpful." Some of his ideas, freed from much of their alloy, are reproduced in the writings of thehistorical school of German economists.

Thereactionaryandfeudalisticthought in Müller's writings, which agreed so little with the spirit of the times, prevented his political ideas from exerting a more notable and lasting influence on his age, while their religious character prevented them from being justly appreciated. However, Müller's teachings had long-term effects in that they were taken up again by 20th century theorists ofcorporatismand thecorporate state,for exampleOthmar Spann(Der wahre Staat. Vorlesungen über Abbruch und Neubau der Gesellschaft,Vienna, 1921).

Simonde de Sismondi[edit]

The first critic oflaissez-fairecapitalism from a standpoint not decidedly feudal, was theSwisseconomistSimonde de Sismondi,whose theories are known as "economic Romanticism". As an economist, Sismondi represented a humanitarian protest against the dominant orthodoxy of his time. In his principal work,Nouveaux principes d'économie politique(1819), he insisted on the fact that economic science studied the means of increasing wealth too much, and the use of wealth for producing happiness, too little. Sismondi contrasted the peaceful, simple trade in goods and an age of crisis and mass unemployment. He wrote, "Let us beware of this dangerous theory of equilibrium which is supposed to be automatically established. A certain kind ofequilibrium,it is true, is reestablished in the long run, but it is after a frightful amount of suffering. "While he was not asocialist,in protesting against laissez faire and invoking the state "to regulate the progress of wealth" he was an interesting precursor of the GermanHistorical school of economics,on whose theories the Europeanwelfare statesof social benefits were based.[9]

Vladimir Leninstated that "the reactionary point of view of the Romantic Sismondi lies not at all in the fact that he wanted to return to the Middle Ages, but in the fact that he compared the present with the past, and not with the future, that he proved the eternal needs of society through ruins and not through the tendencies of recent development".[4][2]

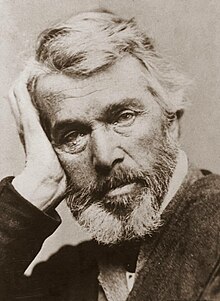

Thomas Carlyle[edit]

British philosopher and mathematicianThomas Carlyle,a promoter of German Romantic literature in Britain, was before 1848 a leading representative of the Romantic economic criticism of capitalism, characterized byGyörgy Lukácsas "one of the most astute and insightful critics of the emerging capitalist relations of production, highlighting its destructive influence over old forms of social organization in hiswritingson theFrench Revolution... [Carlyle] in his works prior to 1848, waged an untiring campaign of exposure against the prevalent capitalism, against those who praised it for its unproblematic progressiveness, and against the mendacious theory that this progress served the interest of the working people. "[10]Carlyle contrasted the ordered and purposefulartisanlabour in theMiddle Ageswith the division of labour and an age of anarchy in modern capitalism, and found the Middle Ages to be better.

Carlyle's attacks on the ills ofindustrialisationand onclassical economicswere an important inspiration forU.S. progressives.[11]In particular, Carlyle criticisedJohn Stuart Mill's economic ideas for supporting Black Emancipation by arguing that Blacks' socio-economic status depended on economic opportunities rather than heredity.[12]Carlyle's racist justification foreconomic statismevolved into theelitistandeugenicist"intelligent social engineering" promoted early on by the progressiveAmerican Economic Association.[13]

Others[edit]

French authorHonoré de Balzac,although arealistin his writing style and amonarchistin his political convictions, he described everyday life in the period of France's transition from feudalism to capitalism from a position close to that of the Romantic economists. In novels like "La Comédie humaine"and especially"Illusions perdues"depicts with harrowing realism the tumultuous transition of France from feudalism to capitalism and the sorrows these bring to many peoples and classes of people, together with the joys they bring to others. In sympathy with the victims of capitalism, Balzac presents the executors of the judgment, thefinance peoplewho present the bill, as monsters. Insofar as the industrialists appear at all, they are categorized as productive labor inSaint-Simonianfashion. The parasites and bloodsuckers are only thebankersandusurers,not theindustrialists.[14]

In a passage of theGrundrisse,Karl Marxmakes the following remark on the Romantic perspective: "It is as ridiculous to yearn for a return to that original fullness as it is to believe that with this complete emptiness history has come to a standstill. The bourgeois viewpoint has never advanced beyond this antithesis between itself and this romantic viewpoint, and therefore the latter will accompany it as legitimate antithesis up to its blessed end."[15]

Vladimir Leninconsidered the economic theories of the Russianpopulists(Narodniks) of the second half of the 19th century to be a representation of economic Romanticism, writing: "The economic doctrine of the Narodniks is only a Russian variety of general European Romanticism".[4][16][2]

References[edit]

- ^abLöwy, Michael & Sayre, Robert (1984)."Figures of Romantic Anti-Capitalism".New German Critique.New York: Duke University Press for the Cornell University Department of German Studies. pp. 42–92.doi:10.2307/488156.JSTOR488156.

- ^abcLenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1972) [1897]."The Reactionary Character of Romanticism, in: A Characterisation of Economic Romanticism (Sismondi and Our Native Sismondists)"(PDF).Collected Works, Volume 2.Translated by Sdobnikov, Yuri & Hanna, George. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ^Marx, Karl (1942) [1868]."Letter from Marx to Engels In Manchester".Marx-Engels Correspondence 1868, in: Collected Works of Marx and Engels.London: Progress Publishers.

- ^abcVishnevsky, A. (1941)."Романтизм".Great Soviet Encyclopedia, ed. 1, vol. 49.Moscow.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Marx, Karl & Engels, Friedrich (1976)."Preface".Marx and Engels On Literature and Art.Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ^abcFichte, Johann Gottlieb (1800).The Closed Commercial State.Translated by Blunden, Andy.

- ^abcShulyatikov, Vladimir Mikhailovich (1908)."Фихте, Шеллинг, Гегель.".Оправдание капитализма в западноевропейской философии.Moscow.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Eastern Europe: An Historical Geography, 1815-1945p23

- ^One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Sismondi, Jean Charles Leonard de".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 159.

- ^Lukács, György (1980). "Marx and the Problem of Ideological Decay".Essays on Realism.Translated by Fernbach, David. London: Lawrence and Wishart Ltd.

- ^Gutzke, D. (2016-04-30).Britain and Transnational Progressivism.Springer.ISBN978-0-230-61497-0.

- ^Carlyle, Thomas.Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question.

- ^Leonard, Thomas C. (2016-01-12).Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era(Reprint ed.). Princeton University Press.

- ^Adorno, Theodor W. (1958)."Reading Balzac"(PDF).Notes to Literature, Volume 1.Translated by Weber Nicholsen, Shierry. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^Marx, Karl (1973) [1857]."Grundrisse: Notebook I – The Chapter on Money".Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie.Translated by Nicolaus, Martin. London: Penguin Press.

- ^Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1972) [1897]."The Heritage We Renounce".Collected Works, Volume 2.Translated by Sdobnikov, Yuri & Hanna, George. Moscow: Progress Publishers.