Chicken

| Chicken | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male (left) and female chickens | |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Gallus |

| Species: | G. g. domesticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gallus gallus domesticus | |

| |

| Chicken distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gallus domesticusL. | |

Thechicken(Gallus domesticus) is a large and round short-wingedbird,domesticatedfrom thered junglefowlofSoutheast Asiaaround 8,000 years ago. Most chickens are raised for food, providingmeatandeggs;others are kept aspetsor forcockfighting.

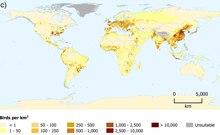

Chickens are common and widespread domestic animals, with a total population of 23.7 billion as of 2018[update],and an annual production of more than 50 billion birds. A hen bred for laying can produce over 300 eggs per year. There are numerouscultural references to chickensin folklore, religion, and literature.

Nomenclature

Terms for chickens include:

- Biddy:a chicken, or a newly hatched chicken[1][2]

- Capon:a castrated orneuteredmale chicken[a]

- Chick:a young chicken[3]

- Chook/tʃʊk/:a chicken (Australia/New Zealand, informal)[4]

- Cock:a fertile adult male chicken[5][6]

- Cockerel:a young male chicken[7]

- Hen:an adult female chicken[8]

- Pullet:a young female chicken less than a year old.[9]In the poultry industry, a pullet is a sexually immature chicken less than 22 weeks of age.[10]

- Rooster:a fertile adult male chicken, especially in North America. Originated in the 18th century, possibly as a euphemism to avoid the sexual connotation of the wordcock.[11][12][13]

- Yardbird:a chicken (southern United States, dialectal)[14]

Chickencan mean achick,as inWilliam Shakespeare's playMacbeth,whereMacdufflaments the death of "all my pretty chickens and their dam".[15]The usage is preserved in placenames such as theHen and Chicken Islands.[16]In older sources, and still often in trade and scientific contexts, chickens as a species are described ascommon fowlordomestic fowl.[17]

Description

Chickens are relatively largebirds,active by day.The body is round, the legs are unfeathered in most breeds, and the wings are short.[18]Wildjunglefowlcanfly;chickens and theirflight musclesare too heavy to allow them to fly more than a short distance.[19]Size and coloration vary widely between breeds.[18]Adult chickens of both sexes have a fleshy crest on their heads called a comb or cockscomb, and hanging flaps of skin on either side under their beaks calledwattles;combs and wattles aremore prominent in males.Some breeds have amutationthat causes extra feathering under the face, giving the appearance of a beard.[20]

Chickens areomnivores.[21]In the wild, they scratch at the soil to search for seeds, insects, and animals as large aslizards,small snakes,[22]and youngmice.[23]A chicken may live for 5–10 years, depending on thebreed.[24]The world's oldest known chicken lived for 16 years.[25]

Chickens aregregarious,living inflocks,andincubate eggsand raise young communally. Individual chickens dominate others, establishing apecking order;dominant individuals take priority for access to food and nest sites. The concept of dominance, involving pecking, was described in female chickens byThorleif Schjelderup-Ebbein 1921 as the "pecking order".[26][27]Male chickens tend to leap and use their claws in conflicts.[28]Chickens are capable of mobbing and killing a weak or inexperienced predator, such as a young fox.[29]

A male's crowing is a loud and sometimes shrill call, serving as a territorial signal to other males,[30]and in response to sudden disturbances within their surroundings. Hens cluck loudly after laying aneggand to call their chicks. Chickens give differentwarning callsto indicate that apredatoris approaching from the air or on the ground.[31]

Reproduction and life-cycle

To initiate courting, some roosters may dance in a circle around or near a hen (a circle dance), often lowering the wing which is closest to the hen.[32]The dance triggers a response in the hen[32]and when she responds to his call, the rooster may mount the hen and proceed with the mating. Mating typically involves a sequence in which the male approaches the female and performs a waltzing display. If the female is unreceptive, she runs off; otherwise, she crouches, and the male mounts, treading with both feet on her back. After copulation the male does a tail-bending display.[33]

Sperm transfer occurs bycloacalcontact between the male and female, in an action called the 'cloacal kiss'.[34]As with all birds, reproduction is controlled by aneuroendocrinesystem, theGonadotropin-Releasing Hormone-I neuronsin thehypothalamus.Reproductive hormones includingestrogen,progesterone,andgonadotropins(luteinizing hormoneandfollicle-stimulating hormone) initiate and maintain sexual maturation changes. Reproduction declines with age, thought to be due to a decline in GnRH-I-N.[35]

Hens often try to lay in nests that already contain eggs and sometimes move eggs from neighbouring nests into their own. A flock thus uses only a few preferred locations, rather than having a different nest for every bird.[36]Under natural conditions, most birds lay only until aclutchis complete; they then incubate all the eggs. This is called "goingbroody".The hen sits on the nest, fluffing up or pecking defensively if disturbed. She rarely leaves the nest until the eggs have hatched.[37]

Eggs of chickens from the high-altitude region ofTibethave special physiological adaptations that result in a higher hatching rate in low oxygen environments. When eggs are placed in a hypoxic environment, chicken embryos from these populations express much morehemoglobinthan embryos from other chicken populations. This hemoglobin has a greater affinity for oxygen, binding oxygen more readily.[38]

Fertile chicken eggs hatch at the end of the incubation period, about 21 days; the chick uses itsegg toothto break out of the shell.[32]Hens remain on the nest for about two days after the first chick hatches; during this time the newly hatched chicks feed by absorbing the internalyolk sac.[39]The hen guards her chicks and brood them to keep them warm. She leads them to food and water and calls them towards food. The chicksimprinton the hen and subsequently follow her continually. She continues to care for them until they are several weeks old.[40]

Inbreeding of White Leghorn chickens tends to causeinbreeding depressionexpressed as reduced egg number and delayed sexual maturity.[41]Strongly inbred Langshan chickens display obvious inbreeding depression in reproduction, particularly for traits such as age when the first egg is laid and egg number.[42]

Origin

Phylogeny

Water or ground-dwelling fowl similar to modernpartridges,in theGalliformes,theorderof bird that chickens belong to, survived theCretaceous–Paleogene extinction eventthat killed all tree-dwelling birds and theirdinosaurrelatives.[43]Chickens are descended primarily from thered junglefowl(Gallus gallus) and are scientifically classified as the same species.[44]Domesticated chickens freely interbreed with populations of red junglefowl.[44]The domestic chicken has subsequently hybridised withgrey junglefowl,Sri Lankan junglefowlandgreen junglefowl;[45]a gene for yellow skin, for instance, was incorporated into domestic birds from the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).[46]It is estimated that chickens share between 71 and 79% of their genome with red junglefowl.[45]

Domestication

According to one early study, a single domestication event of the red junglefowl in present-dayThailandgave rise to the modern chicken with minor transitions separating the modern breeds.[49]The red junglefowl is well adapted to take advantage of thevast quantities of seedproduced during the end of themulti-decade bamboo seeding cycle,to boost its own reproduction.[50]In domesticating the chicken, humans took advantage of the red junglefowl's ability to reproduce prolifically when exposed to a surge in its food supply.[51]

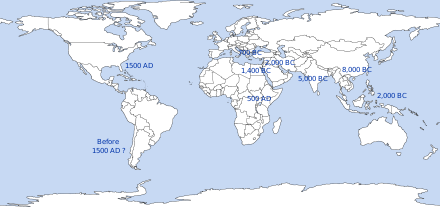

Exactly when and where the chicken was domesticated remains controversial. Genomic studies estimate that the chicken was domesticated 8,000 years ago[45]in Southeast Asia and spread to China and India 2,000 to 3,000 years later. Archaeological evidence supports domestic chickens in Southeast Asia well before 6000 BC, China by 6000 BC and India by 2000 BC.[45][52][53]A landmark 2020 Nature study that fully sequenced 863 chickens across the world suggests that all domestic chickens originate from a single domestication event of red junglefowl whose present-day distribution is predominantly in southwestern China, northern Thailand and Myanmar. These domesticated chickens spread across Southeast and South Asia where they interbred with local wild species of junglefowl, forming genetically and geographically distinct groups. Analysis of the most popular commercial breed shows that the White Leghorn breed possesses a mosaic of divergent ancestries inherited from subspecies of red junglefowl.[54][55][56]

Dispersal

Austronesia

A word for the domestic chicken (*manuk) is part of the reconstructedProto-Austronesian language,indicating they weredomesticatedby theAustronesian peoplessince ancient times. Chickens, together with dogs and pigs, were carried throughout the entire range of the prehistoric Austronesian maritime migrations toIsland Southeast Asia,Micronesia,Island Melanesia,Polynesia,andMadagascar,starting from at least 3000 BC fromTaiwan.[57][58][59][60]These chickens might have been introduced duringpre-Columbiantimes toSouth AmericaviaPolynesianseafarers, but evidence for this is still putative.[61]

Americas

The possibility that domestic chickens were in the Americas before Western contact is debated by researchers, but blue-egged chickens, found only in the Americas and Asia, suggest an Asian origin for early American chickens. A lack of data from Thailand, Russia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa makes it difficult to lay out a clear map of the spread of chickens in these areas; better description and genetic analysis of local breeds threatened byextinctionmay also help with research into this area.[62]Chicken bones from theArauco Peninsulainsouth-central Chilewere radiocarbon dated as pre-Columbian, and DNA analysis suggested they were related to prehistoric populations in Polynesia.[47][48]However, further study of the same bones cast doubt on the findings.[63][64]

Eurasia

Chicken remains have been difficult to date, given the small and fragile bird bones; this may account for discrepancies in dates given by different sources. Archaeological evidence is supplemented by mentions in historical texts from the last few centuries BC, and by depictions in prehistoric artworks, such as across Central Asia.[65]Chickens were widespread throughout southern Central Asia by the 4th century BC.[65]

Middle Eastern chicken remains go back to a little earlier than 2000 BC inSyria.[62]Phoenicians spread chickens along the Mediterranean coasts as far as Iberia. During theHellenistic period(4th–2nd centuries BC), in the southernLevant,chickens began to be widely domesticated for food.[66]The first pictures of chickens in Europe are found onCorinthianpotteryof the 7th century BC.[67][68]

Breeding increased under theRoman Empireand reduced in theMiddle Ages.[62]Genetic sequencingof chicken bones from archaeological sites in Europe revealed that in theHigh Middle Ageschickens became less aggressive and began to lay eggs earlier in the breeding season.[69]

Africa

Chickens reached Egypt via the Middle East for purposes ofcockfightingabout 1400 BC and became widely bred in Egypt around 300 BC.[62]Three possible routes of introduction into Africa around the early first millennium AD could have been through the EgyptianNileValley, the East Africa Roman-Greek or Indian trade, or from Carthage and the Berbers, across theSahara.The earliest known remains are fromMali,Nubia,East Coast, andSouth Africaand date back to the middle of the first millennium AD.[62]

Diseases

Chickens are susceptible both toparasitessuch asmites,and todiseasescaused bypathogenssuch asbacteriaandviruses.The parasiteDermanyssus gallinaefeeds on blood, causing irritation and reducing egg production, and acts as a vector for bacterial diseases such assalmonellosisandspirochaetosis.[70] Viral diseases includeavian influenza.[71]

Use by humans

Farming

Chickens are common and widespread domestic animals, with a total population of 23.7 billion as of 2018[update].[72]More than 50 billion chickens are reared annually as a source of meat and eggs.[73]In the United States alone, more than 8 billion chickens are slaughtered each year for meat,[74]and more than 300 million chickens are reared for egg production.[75]The vast majority of poultry is raised infactory farms.According to theWorldwatch Institute,74% of the world's poultry meat and 68% of eggs are produced this way.[76]An alternative to intensive poultry farming isfree-rangefarming. Friction between these two main methods has led to long-term issues ofethical consumerism.Opponents ofintensive farmingargue that it harms the environment, creates human health risks and is inhumane.[77]Advocates of intensive farming say that their efficient systems save land and food resources owing to increased productivity, and that the animals are looked after in a controlled environment.[78]Chickens farmed for meat are calledbroilers.Broiler breeds typically take less than six weeks to reach slaughter size,[79]some weeks longer forfree rangeandorganicbroilers.[80]

Chickens farmed primarily for eggs are called layer hens. The UK alone consumes more than 34 million eggs per day.[81]Hens of some breeds can produce over 300 eggs per year; the highest authenticated rate of egg laying is 371 eggs in 364 days.[82]After 12 months of laying, the commercial hen's egg-laying ability declines to the point where the flock is commercially unviable. Hens, particularly frombattery cagesystems, are sometimes infirm or have lost a significant amount of their feathers, and their life expectancy has been reduced from around seven years to less than two years.[83]In the UK and Europe, laying hens are then slaughtered and used in processed foods, or sold as 'soup hens'.[83]In some other countries, flocks are sometimesforce moultedrather than being slaughtered to re-invigorate egg-laying. This involves complete withdrawal of food (and sometimes water) for 7–14 days[84]or sufficiently long to cause a body weight loss of 25 to 35%,[85]or up to 28 days under experimental conditions.[86]This stimulates the hen to lose her feathers but also re-invigorates egg-production. Some flocks may be force-moulted several times. In 2003, more than 75% of all flocks were moulted in the US.[87]

As pets

Keeping chickens as pets became increasingly popular in the 2000s[88]among urban and suburban residents.[89]Many people obtain chickens for their egg production but often name them and treat them as any other pet like cats or dogs. Chickens provide companionship and have individual personalities. While many do not cuddle much, they will eat from one's hand, jump onto one's lap, respond to and follow their handlers, as well as show affection.[90][91]Chickens are social, inquisitive, intelligent[92]birds, and many people find their behaviour entertaining.[93]Certain breeds, such assilkiesand manybantamvarieties, are generally docile and are often recommended as good pets around children with disabilities.[94]

Cockfighting

Acockfightis a contest held in a ring called a cockpit between two cocks. Cockfighting is outlawed in many countries as involvingcruelty to animals.[95]The activity seems to have been practised in theIndus Valley civilisationfrom 2500 to 2100 BC.[96]In the process of domestication, chickens were apparently kept initially for cockfighting, and only later used for food.[97]

In science

Chickens have long been used asmodel organismsto study developing embryos. Large numbers of embryos can be provided commercially; fertilized eggs can easily be opened and used to observe the developing embryo. Equally important, embryologists can carry out experiments on such embryos, close the egg again and study the effects later in development. For instance, many important discoveries inlimb developmenthave been made using chicken embryos, such as the discovery of theapical ectodermal ridgeand thezone of polarizing activity.[98]

The chicken was the first bird species to have itsgenomesequenced.[99]At 1.21 Gb, the chicken genome is similarly sized compared to other birds, but smaller than nearly all mammals: thehuman genomeis 3.2 Gb.[100]The final gene set contained 26,640 genes (including noncoding genes andpseudogenes), with a total of 19,119 protein-coding genes, a similar number to the human genome.[101]In 2006, scientists researching the ancestry of birds switched on a chickenrecessive gene,talpid2,and found that the embryo jaws initiated formation of teeth, like those found in ancient bird fossils.[102]

In culture, folklore, and religion

Chickens feature widely infolklore,religion,literature,and popular culture. The chicken is a sacred animal in many cultures and deeply embedded in belief systems and religious practices.[103] Roosters are sometimes used fordivination,a practice called alectryomancy. This involves the sacrifice of a sacred rooster, often during a ritualcockfight,used as a form of communication with the gods.[104]InGabriel García Márquez's Nobel-Prize-winning 1967 novelOne Hundred Years Of Solitude,cockfighting is outlawed in the town of Macondo after the patriarch of the Buendia family murders his cockfighting rival and is haunted by the man's ghost.[105]Chicken jokeshave been made at least sinceThe Knickerbockerpublished one in 1847.[106]Chickens have featured in art in farmyard scenes such asAdriaen van Utrecht's 1646Turkeys and ChickensandWalter Osborne's 1885Feeding the Chickens.[107]Thenursery rhyme"Cock a doodle doo",its chorus line imitating the cockerel's call, was published inMother Goose's Melodyin 1765.[108] The 2000 animatedadventurecomedy filmChicken Run,directed byPeter LordandNick Park,featuredanthropomorphicchickens with many chicken jokes.[109][110][111]

-

Etruscanaskos in the form of a rooster, 4th century B.C.

-

Rooster and hen,Đông Hồ folk woodcut,Vietnam

-

Feeding the chickensbyWalter Osborne,1885

-

Joseph Crawhall III,Spanish Cock and Snail,c. 1900

-

Wooden chicken mask,Bali,late 20th century

-

Carved and painted wooden tribal statue of a cock fight,Yoruba,West Africa, c. 2000

Notes

- ^The surgical and chemical castration of chickens is now illegal in some parts of the world.

References

- ^"Definition of biddy | Dictionary".dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2021.RetrievedMay 7,2021.

- ^"Biddy definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary".collinsdictionary.Archivedfrom the original on May 7, 2021.RetrievedMay 7,2021.

- ^"Chick".Cambridge Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on September 7, 2015.

- ^"Chook".Cambridge Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on September 7, 2015.RetrievedMarch 4,2021.

- ^"Cock".Cambridge Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on September 7, 2015.RetrievedMarch 4,2021.

- ^"Hen".Cambridge Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on September 7, 2015.RetrievedMarch 4,2021.

- ^Cockerel.Dictionary.reference.Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2016.RetrievedAugust 29,2010.

- ^"Hen noun".Merriam-Webster.RetrievedFebruary 2,2024.

- ^Pullet.Dictionary.reference.Archivedfrom the original on November 9, 2010.RetrievedAugust 29,2010.

- ^"Overview of the Poultry Industry"(PDF).Overview of the Poultry Industry.Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. p. 8.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 23, 2020.

- ^"Definition of Rooster".merriam-webster.Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2021.RetrievedMarch 6,2021.

- ^Hugh RawsonArchivedJuly 1, 2017, at theWayback Machine"Why Do We Say...? Rooster",American Heritage,August–September 2006.

- ^Online Etymology DictionaryArchivedNovember 11, 2020, at theWayback MachineEntry forrooster (n.),May 2019

- ^Berhardt, Clyde E. B. (1986).I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands.Philadelphia:University of Pennsylvania Press.p. 153.ISBN978-0-8122-8018-0.OCLC12805260.

- ^Shakespeare, William,Macbeth,Act 4 Scene 3, lines 217–229.

- ^"Chicken".Merriam Webster Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on August 21, 2008.RetrievedMarch 4,2021.

- ^Stevens, Lewis,Genetics and evolution of the domestic fowl,p 1 and throughout, 1991, Cambridge University Press,google books

- ^ab"Chicken".Smithsonian's National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute.RetrievedFebruary 2,2024.

- ^Geggel, Laura (December 8, 2016)."Forget About the Road. Why Are Chickens So Bad at Flying?".Live Science.RetrievedFebruary 3,2024.

- ^Ying Guo, Xiaorong Gu, Zheya Sheng, Yanqiang Wang, Chenglong Luo, Ranran Liu, Hao Qu, Dingming Shu, Jie Wen, Richard P. M. A. Crooijmans, Örjan Carlborg, Yiqiang Zhao, Xiaoxiang Hu, Ning Li (2016).A Complex Structural Variation on Chromosome 27 Leads to the Ectopic Expression of HOXB8 and the Muffs and Beard Phenotype in ChickensArchivedNovember 5, 2021, at theWayback Machine.PLoS Genetics.12(6): e1006071.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006071.

- ^"Info on Chicken Care".Ideas-4-pets.co.uk.2003. Archived fromthe originalon June 25, 2015.RetrievedAugust 13,2008.

- ^D Lines (July 27, 2013)."Chicken Kills Rattlesnake".YouTube.Archivedfrom the original on December 11, 2021.RetrievedMarch 13,2019.

- ^Gerard P.Worrell AKA "Farmer Jerry"."Frequently asked questions about chickens & eggs".Gworrell.freeyellow.Archivedfrom the original on September 16, 2008.RetrievedAugust 13,2008.

- ^"The Poultry Guide – A to Z and FAQs".Ruleworks.co.uk.Archived fromthe originalon November 28, 2010.RetrievedAugust 29,2010.

- ^Smith, Jamon (August 6, 2006)."World's oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show'".Tuscaloosa News.Alabama, USA.Archivedfrom the original on February 20, 2019.RetrievedMay 18,2020.

- ^Perrin, P. G. (1955). "'Pecking order' 1927–54 ".American Speech.30(4): 265–268.doi:10.2307/453561.ISSN0003-1283.JSTOR453561.

- ^Schjelderup-Ebbe, T. (1975). "Contributions to the social psychology of the domestic chicken [Schleidt M., Schleidt, W. M., translators]". In Schein, M. W. (ed.).Social Hierarchy and Dominance. Benchmark Papers in Animal Behavior.Vol. 3. Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross. pp. 35–49.(Reprinted fromZeitschrift für Psychologie,1922, 88:225-252.)

- ^Rajecki, D. W. (1988). "Formation of leap orders in pairs of male domestic chickens".Aggressive Behavior.14(6): 425–436.doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1988)14:6<425::AID-AB2480140604>3.0.CO;2-#.S2CID141664966.

- ^AFP (March 12, 2019)."Chickens 'teamed up to kill fox' at Brittany farming school".Theguardian.Archivedfrom the original on March 13, 2019.RetrievedMarch 13,2019.

- ^"Top cock: Roosters crow in pecking order".Phys.org.Archivedfrom the original on January 15, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 14,2018.

- ^Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1993). "On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system".Animal Behaviour.46(1): 23–38.doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1158.S2CID53165305.

- ^abcGrandin, Temple;Johnson, Catherine (2005).Animals in Translation.New York City:Scribner's.pp.69–71.ISBN978-0-7432-4769-6.

- ^Cheng, Kimberly M.; Burns, Jeffrey T. (August 1988). "Dominance Relationship and Mating Behavior of Domestic Cocks: A Model to Study Mate-Guarding and Sperm Competition in Birds".The Condor.90(3): 697–704.doi:10.2307/1368360.JSTOR1368360.

- ^Briskie, J. V.; R. Montgomerie (1997). "Sexual Selection and the Intromittent Organ of Birds".Journal of Avian Biology.28(1): 73–86.doi:10.2307/3677097.JSTOR3677097.

- ^Bain, M. M.; Nys, Y.; Dunn, I.C. (May 3, 2016)."Increasing persistency in lay and stabilising egg quality in longer laying cycles. What are the challenges?".British Poultry Science.57(3).Taylor & Francis:330–338.doi:10.1080/00071668.2016.1161727.PMC4940894.PMID26982003.S2CID17842329.

- ^Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). "Factors influencing floor-laying by hens in modified cages".Applied Animal Behaviour Science.36(2–3): 211–222.doi:10.1016/0168-1591(93)90011-d.

- ^"Why Do Chickens Puff up Their Feathers? I 4 Reasons Explained".August 8, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on June 18, 2021.RetrievedJune 16,2021.

- ^Zhang, H.; Wang, X.T.; Chamba, Y.; Ling, Y.; Wu, C.X. (October 2008)."Influences of Hypoxia on Hatching Performance in Chickens with Different Genetic Adaptation to High Altitude".Poultry Science.87(10): 2112–2116.doi:10.3382/ps.2008-00122.PMID18809874.

- ^Ali, A.; Cheng, K.M. (1985)."Early egg production in genetically blind (rc/rc) chickens in comparison with sighted (Rc+/rc) controls".Poultry Science.64(5): 789–794.doi:10.3382/ps.0640789.PMID4001066.

- ^Edgar, Joanne; Held, Suzanne; Jones, Charlotte; Troisi, Camille (January 5, 2016)."Influences of Maternal Care on Chicken Welfare".Animals.6(1): 2.doi:10.3390/ani6010002.PMC4730119.PMID26742081.

- ^Sewalem, A.; Johansson, K.; Wilhelmson, M.; Lillpers, K. (1999). "Inbreeding and inbreeding depression on reproduction and production traits of White Leghorn lines selected for egg production traits".British Poultry Science.40(2): 203–208.doi:10.1080/00071669987601.

- ^Xue, Qian; Li, Guohui; Cao, Yuxia; Yin, Jianmei; Zhu, Yunfen; Zhang, Huiyong; Zhou, Chenghao; Shen, Haiyu; Dou, Xinhong; Su, Yijun; Wang, Kehua; Zou, Jianmin; Han, Wei (June 1, 2021)."Identification of genes involved in inbreeding depression of reproduction in Langshan chickens".Animal Bioscience.34(6): 975–984.doi:10.5713/ajas.20.0248.ISSN2765-0189.PMC8100482.PMID33152217.

- ^Pennisi, Elizabeth(May 24, 2018). "Quaillike creatures were the only birds to survive the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact".Science.doi:10.1126/science.aau2802.

- ^abWong, G. K.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. (December 9, 2004)."A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single nucleotide polymorphisms".Nature.432(7018): 717–722.Bibcode:2004Natur.432..717B.doi:10.1038/nature03156.PMC2263125.PMID15592405.

- ^abcdeLawal, Raman Akinyanju; Martin, Simon H.; Vanmechelen, Koen; Vereijken, Addie; Silva, Pradeepa; Al-Atiyat, Raed Mahmoud; et al. (December 2020)."The wild species genome ancestry of domestic chickens".BMC Biology.18(1): 13.doi:10.1186/s12915-020-0738-1.PMC7014787.PMID32050971.

- ^Eriksson, Jonas; Larson, Greger; Gunnarsson, Ulrika; Bed'hom, Bertrand; Tixier-Boichard, Michele; Strömstedt, Lina; et al. (February 29, 2008)."Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken".PLOS Genetics.4(2): e1000010.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000010.PMC2265484.PMID18454198.

- ^abBorrell, Brendan (June 1, 2007)."DNA reveals how the chicken crossed the sea".Nature.447(7145): 620–621.Bibcode:2007Natur.447R.620B.doi:10.1038/447620b.PMID17554271.S2CID4418786.

- ^abStorey, A. A. (June 19, 2007)."Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.104(25). et al.: 10335–10339.Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410335S.doi:10.1073/pnas.0703993104.PMC1965514.PMID17556540.

- ^Fumihito, A.; Miyake, T.; Sumi, S.; Takada, M.; Ohno, S.; Kondo, N. (December 20, 1994), "One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds",PNAS,91(26): 12505–12509,Bibcode:1994PNAS...9112505F,doi:10.1073/pnas.91.26.12505,PMC45467,PMID7809067

- ^King, Rick (February 24, 2009),"Rat Attack",Nova and National Geographic Television,archivedfrom the original on August 23, 2017,retrievedAugust 25,2017

- ^King, Rick (February 1, 2009),"Plant vs. Predator",NOVA,archivedfrom the original on August 21, 2017,retrievedAugust 25,2017

- ^West, B.; Zhou, B.X. (1988). "Did chickens go north? New evidence for domestication".J. Archaeol. Sci.14(5): 515–533.Bibcode:1988JArSc..15..515W.doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90080-5.

- ^Al-Nasser, A.; Al-Khalaifa, H.; Al-Saffar, A.; Khalil, F.; Albahouh, M.; Ragheb, G.; Al-Haddad, A.; Mashaly, M. (June 1, 2007). "Overview of chicken taxonomy and domestication".World's Poultry Science Journal.63(2): 285–300.doi:10.1017/S004393390700147X.S2CID86734013.

- ^Wang, Ming-Shan; Thakur, Mukesh; Peng, Min-Sheng; Jiang, Yu; Frantz, Laurent Alain François; Li, Ming; et al. (2020)."863 genomes reveal the origin and domestication of chicken".Cell Research.30(8): 693–701.doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0349-y.PMC7395088.PMID32581344.S2CID220050312.

- ^Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; et al. (January 2006). "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.38(1): 12–19.doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014.PMID16275023.

- ^Zeder, Melinda A.; Emshwiller, Eve; Smith, Bruce D.; Bradley, Daniel G. (March 2006). "Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology".Trends in Genetics.22(3): 139–155.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.007.PMID16458995.

- ^abThomson, Vicki A. (April 2014)."Using ancient DNA to study the origins and dispersal of ancestral Polynesian chickens across the Pacific".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.111(13). et al.: 4826–4831.Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4826T.doi:10.1073/pnas.1320412111.PMC3977275.PMID24639505.

- ^Piper, Philip J. (2017)."The Origins and Arrival of the Earliest Domestic Animals in Mainland and Island Southeast Asia: A Developing Story of Complexity".In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.).New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory.terra australis. Vol. 45.ANU Press.ISBN9781760460945.Archivedfrom the original on November 28, 2022.RetrievedMay 5,2023.

- ^Meleisea, Malama (March 25, 2004).The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders.Cambridge University Press.p. 56.ISBN9780521003544.Archivedfrom the original on September 13, 2016.RetrievedMarch 13,2019.

- ^Crawford, Michael H. (March 13, 2019).Anthropological Genetics: Theory, Methods and Applications.Cambridge University Press.p. 411.ISBN9780521546973.Archivedfrom the original on September 13, 2016.RetrievedMarch 13,2019– via Google Books.

- ^Neumann, Scott (March 18, 2014)."Study: The Chicken Didn't Cross The Pacific To South America".The Two Way.NPR.Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2023.RetrievedMay 5,2023.

- ^abcdeThe Cambridge History of Food, 2000,Cambridge University Press,vol.1, pp. 496-499

- ^Gongora, Jaime (2008)."Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA".PNAS.105(30). et al.: 10308–10313.Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510308G.doi:10.1073/pnas.0801991105.PMC2492461.PMID18663216.

- ^Thomson, Vicki A. (April 1, 2014)."Using ancient DNA to study the origins and dispersal of ancestral Polynesian chickens across the Pacific".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.111(13). et al.: 4826–4831.Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4826T.doi:10.1073/pnas.1320412111.PMC3977275.PMID24639505.

- ^abPeters, Carli (April 2, 2024)."Archaeological and molecular evidence for ancient chickens in Central Asia".Nature Communications.15(1). et al.doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46093-2.ISSN2041-1723.PMC10987595.PMID38565545.

- ^Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (August 11, 2015)."Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.112(32): 9849–9854.Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9849P.doi:10.1073/pnas.1504236112.PMC4538678.PMID26195775.

- ^Karayanis, Dean; Karayanis, Catherine (March 13, 2019).Regional Greek Cooking.Hippocrene Books.p. 176.ISBN9780781811460.Archivedfrom the original on September 13, 2016.RetrievedMarch 13,2019– via Google Books.

- ^Chiffolo, Anthony F.; Hesse, Rayner W. (March 13, 2019).Cooking with the Bible: Biblical Food, Feasts, and Lore.Greenwood Publishing Group.p. 207.ISBN9780313334108.Archivedfrom the original on September 13, 2016.RetrievedMarch 13,2019– via Google Books.

- ^Brown, Marley (September–October 2017)."Fast Food".Archaeology.70(5): 18.ISSN0003-8113.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2019.RetrievedJuly 25,2019.

- ^Schiavone, Antonella; Pugliese, Nicola; Otranto, Domenico; Samarelli, Rossella; Circella, Elena; De Virgilio, Caterina; Camarda, Antonio (January 20, 2022)."Dermanyssus gallinae:the long journey of the poultry red mite to become a vector ".Parasites & Vectors.15(1): 29.doi:10.1186/s13071-021-05142-1.ISSN1756-3305.PMC8772161.PMID35057849.

- ^Barjesteh, Neda; O'Dowd, Kelsey; Vahedi, Seyed Milad (March 2020)."Antiviral responses against chicken respiratory infections: Focus on avian influenza virus and infectious bronchitis virus".Cytokine.127:154961.doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154961.PMC7129915.PMID31901597.

- ^"Number of chickens worldwide from 1990 to 2018".Statista.Archivedfrom the original on November 27, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 23,2020.

- ^"About chickens".Compassion in World Farming.Archivedfrom the original on April 26, 2017.RetrievedApril 25,2017.

- ^Fereira, John."Poultry Slaughter Annual Summary".usda.mannlib.cornell.edu.Archivedfrom the original on April 26, 2017.RetrievedApril 25,2017.

- ^Fereira, John."Chickens and Eggs Annual Summary".usda.mannlib.cornell.edu.Archivedfrom the original on April 26, 2017.RetrievedApril 25,2017.

- ^"Towards Happier Meals In A Globalized World".Worldwatch Institute.Archived fromthe originalon May 29, 2014.RetrievedMay 29,2014.

- ^Ilea, Ramona Cristina (April 2009). "Intensive Livestock Farming: Global Trends, Increased Environmental Concerns, and Ethical Solutions".Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics.22(2): 153–167.doi:10.1007/s10806-008-9136-3.S2CID154306257.

- ^Tilman, David; Cassman, Kenneth G.; Matson, Pamela A.; Naylor, Rosamond; Polasky, Stephen (August 2002). "Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices".Nature.418(6898): 671–677.Bibcode:2002Natur.418..671T.doi:10.1038/nature01014.PMID12167873.S2CID3016610.

- ^"Broiler Chickens Fact Sheet".Animals Australia.Archivedfrom the original on July 12, 2010.RetrievedAugust 29,2010.

- ^"Chickens Farmed for Meat".Compassion in World Farming.RetrievedFebruary 2,2024.

- ^"UK Egg Industry Data".Official Egg Info.Archivedfrom the original on December 30, 2016.RetrievedApril 25,2017.

- ^Glenday, Craig (April 26, 2011).Guinness World Records 2011.Jim Pattison Group.p. 286.ISBN978-0440423102.

- ^abBrowne, Anthony (March 10, 2002)."Ten weeks to live".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on May 16, 2008.RetrievedApril 28,2010.

- ^Patwardhan, D.; King, A. (2011). "Review: feed withdrawal and non feed withdrawal moult".World's Poultry Science Journal.67(2): 253–268.doi:10.1017/s0043933911000286.S2CID88353703.

- ^Webster, A.B. (2003)."Physiology and behavior of the hen during induced moult".Poultry Science.82(6): 992–1002.doi:10.1093/ps/82.6.992.PMID12817455.

- ^Molino, A.B.; Garcia, E.A.; Berto, D.A.; Pelícia, K.; Silva, A.P.; Vercese, F. (2009)."The Effects of Alternative Forced-Molting Methods on The Performance and Egg Quality of Commercial Layers".Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science.11(2): 109–113.doi:10.1590/s1516-635x2009000200006.hdl:11449/14340.

- ^Yousaf, M.; Chaudhry, A.S. (March 1, 2008)."History, changing scenarios and future strategies to induce moulting in laying hens"(PDF).World's Poultry Science Journal.64(1): 65–75.doi:10.1017/s0043933907001729.S2CID34761543.Archived(PDF)from the original on November 24, 2020.RetrievedOctober 23,2020.

- ^Fly, Colin (July 27, 2007)."Some homeowners find chickens all the rage".Chicago Tribune.[permanent dead link]

- ^Pollack-Fusi, Mindy (December 16, 2004)."Cooped up in suburbia".Boston Globe.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedJune 4,2020.

- ^Kreilkamp, Ivan (November 25, 2020)."How Caring for Backyard Chickens Stretched My Emotional Muscles".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 25, 2020.

- ^Boone, Lisa (August 27, 2017)."Chickens will become a beloved pet — just like the family dog".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on April 2, 2019.RetrievedApril 3,2019.

- ^Barras, Colin."Despite what you might think, chickens are not stupid".bbc.Archived fromthe originalon June 5, 2021.RetrievedSeptember 6,2020.

- ^United Poultry Concerns."Providing a Good Home for Chickens".Archivedfrom the original on June 5, 2009.RetrievedMay 4,2009.

- ^"Choosing Your Chickens".Clucks and Chooks.Archivedfrom the original on July 30, 2009.

- ^Raymond Hernandez (April 11, 1995)."A Blood Sport Gets in the Blood; Fans of Cockfighting Don't Understand Its Outlaw Status".The New York Times.New York City Metropolitan Area.RetrievedMay 10,2014.

- ^Crawford, R. D. (1990).Poultry Breeding and Genetics.Elsevier.pp. 10–11.ISBN978-0444885579.OL2207173M.

- ^Lawler, Andrew; Adler, Jerry (June 2012)."How the Chicken Conquered the World".Smithsonian Magazine(June 2012).

- ^Young, John J.; Tabin, Clifford J. (September 2017)."Saunders's framework for understanding limb development as a platform for investigating limb evolution".Developmental Biology.429(2): 401–408.doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.11.005.PMC5426996.PMID27840200.

- ^International Chicken Genome Sequencing Consortium (December 9, 2004)."Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution".Nature.432(7018): 695–716.Bibcode:2004Natur.432..695C.doi:10.1038/nature03154.PMID15592404.

- ^Gregory, T. Ryan (September 2005). "Synergy between sequence and size in Large-scale genomics".Nature Reviews Genetics.6(9): 699–708.doi:10.1038/nrg1674.PMID16151375.S2CID24237594.

- ^Warren, Wesley C.; Hillier, LaDeana W.; Tomlinson, Chad; Minx, Patrick; Kremitzki, Milinn; Graves, Tina; et al. (January 2017)."A New Chicken Genome Assembly Provides Insight into Avian Genome Structure".G3.7(1): 109–117.doi:10.1534/g3.116.035923.PMC5217101.PMID27852011.

- ^Scientists Find Chickens Retain Ancient Ability to Grow TeethArchivedJune 20, 2008, at theWayback MachineAmmu Kannampilly,ABC News,February 27, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ^Adler, Jerry; Lawler, Andrew (June 2012)."How the Chicken Conquered the World".Smithsonian.Archivedfrom the original on November 3, 2012.RetrievedMay 24,2012.

- ^Encyclopædia Perthensis; Or Universal Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, Literature, &c. Intended to Supersede the Use of Other Books of Reference.Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). John Brown. 1816. p. 394.

- ^"Love and Immolation in Argentina".Washington Post.August 16, 1981.

- ^The Knickerbocker, or The New York Monthly,March 1847, p. 283.

- ^Kellogg, Diane M. (May 22, 2020)."Chickens in Art History".Painting World Magazine. Archived fromthe originalon February 2, 2024.RetrievedFebruary 2,2024.

- ^Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1997) [1951].The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes(2nd ed.).Oxford University Press.p. 128.

- ^Corliss, Richard (December 4, 2000)."Run, Chicken Run!".Time.ISSN0040-781X.Archivedfrom the original on January 24, 2023.RetrievedMarch 23,2023.

- ^"AFI|Catalog".Archivedfrom the original on August 17, 2018.RetrievedAugust 17,2018.

- ^"'Chicken' Recipe Simply Divine / Action comedy blends great story, animation ".SFGate.June 21, 2000.Archivedfrom the original on June 2, 2021.RetrievedJune 2,2021.

External links

Data related toGallus gallus domesticusat Wikispecies

Data related toGallus gallus domesticusat Wikispecies