Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg | |

|---|---|

Luxemburg,c. 1895–1905 | |

| Born | Rozalia Luksenburg 5 March 1871 Zamość,Congress Poland,Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 January 1919(aged 47) |

| Cause of death | Execution by shooting |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich(Dr. jur., 1897) |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Gustav Lübeck

(m.1897,divorced) |

| Partners | |

| Parent(s) | Edward Eliasz Luksenburg Lina Lewensztejn |

| Relatives | de:Nathan Löwenstein von Opoka(cousin) |

| Signature | |

| Part ofa seriesabout |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

|

| Part ofa serieson |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

Rosa Luxemburg(Polish:Róża Luksemburg,[ˈruʐaˈluksɛmburk];German:[ˈʁoːzaˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk];bornRozalia Luksenburg;5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-Germanrevolutionary socialist,orthodox Marxist,andanti-War activistduring theFirst World War.She became a key figure of the revolutionary socialist movements of Poland and Germany during the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly theSpartacist uprising.

Born and raised in asecular Jewishfamily inCongress Poland,she became aGermancitizen in 1897. The same year, she was awarded aDoctor of Lawinpolitical economyfrom theUniversity of Zurich,becoming one of the first women in Europe to do so. Successively, she was a member of theProletariatparty, theSocial Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania(SDKPiL), theSocial Democratic Party of Germany(SPD), theIndependent Social Democratic Party(USPD), theSpartacus League(Spartakusbund), and theCommunist Party of Germany(KPD).

After the SPD supported German involvement inWorld War Iin 1915, Luxemburg andKarl Liebknechtco-founded the anti-war Spartacus League which eventually became the KPD. During theNovember Revolution,she co-founded the newspaperDie Rote Fahne(The Red Flag), the central organ of the Spartacist movement. Luxemburg considered the Spartacist uprising of January 1919 a blunder,[1]but supported the attempted overthrow of the SPD-ruledWeimar Republicand rejected any attempt at a negotiated solution.Friedrich Ebert's SPD Cabinet crushed the revolt and theSpartakusbundby sending in theFreikorps,government-sponsoredparamilitary groupsconsisting mostly of battle-hardened World War I veterans of theImperial German Army.Freikorpstroops captured, tortured and executed[2]Luxemburg and Liebknecht during the rebellion.[3]

Due to her pointed criticism of both theLeninistand the more moderatesocial democraticschools ofMarxism,Luxemburg has always had a somewhat ambivalent reception among scholars and theorists of thepolitical left.[4]Nonetheless, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were extensively idolised as communistmartyrsby theEast Germancommunist government.[5]The GermanFederal Office for the Protection of the Constitution(BVS) asserts that idolization of Luxemburg and Liebknecht is an important tradition of the 21st-century German far-left.[5]Despite her own Polish nationality and strong ties to Polish culture, opposition from thePolish Socialist Partydue to her stance against the 1918 independence of theSecond Polish Republicand later criticism from Stalinists have made her a controversial historical figure in the present-day political discourse of theThird Polish Republic.[6][7][8]

Life[edit]

Poland[edit]

Ancestry[edit]

Little is known about Rozalia's great-grandparents, Elisza and Szayndla, but according to historical evidence it is likely they lived inWarsaw.[9]Their son, Rosa's grandfather, Abraham Luxemburg probably lived in Warsaw before marrying Chana Szlam (Rosa's grandmother) and moving toZamość.[9]Abraham built a successful timber business there, based in Zamość and Warsaw but with links as far away asDanzig,Leipzig,Berlin,andHamburg;although coming from humble origins, he became a wealthy businessman with transnational connections who could afford to provide for his children an education abroad in theGerman Empire.[8][9]He supported theJewish Reform movement,becoming a prominent member of the ZamośćMaskilim.[9]He was committed toJewish emancipation,spokePolishandYiddish,and ensured that his children spoke these tongues too; it is unclear whether he took part in theNovember Uprising(1830–31) or not.[9]

Abraham's son Edward was Róża's father.[9]He was born in Zamość on 17 December 1830, the eldest of ten siblings and heir to his father's timber business.[9][8]Edward Eliasz Luxenburg lost his mother at the age of 18. He met his wife Lina Löwenstein through his stepmother Amalia, who was Lina's older sister.[9]Lina and Amalia were daughters of the Rabbi ofMeseritz,Isaak Ozer Löwenstein, and their brother was the reform Rabbi Isachar Dov Berish (Bernhard) Löwenstein ofLemberg.[9]Lina and Edward married around 1853 and lived together in Zamość, where Edward worked with his father.[9]Like his father, Edward was a leading member of the Reform Jewish community in the city.[9]When theJanuary Uprisingbroke out, Edward delivered weapons to Polish partisans and organised fundraisers for the insurrection.[8]After the fall of the uprising he became a target of the tsarist police and was forced into hiding in Warsaw, leaving his family behind in Zamość.[9]During the 1860s and 1870s, Edward moved frequently and experienced financial difficulties; eventually the rest of the family, including two-year-old Rosa, joined him in Warsaw in 1873.[9][10]

Origins[edit]

Róża Luksemburg, actual birth name Rozalia Luksenburg, was born on 5 March 1871 at 45 Ogrodowa Street (now 7a Kościuszko Street)[9]in Zamość.[11][12]The Luxemburg family werePolish Jewsliving in theRussian sector of Poland,after the country waspartitionedbyPrussia,RussiaandAustriaalmost a century earlier. She was the fifth and youngest child of Edward Eliasz Luxemburg and Lina Löwenstein. Her father Edward, like his father Abraham, supported the Jewish Reform movement. Luxemburg later stated that her father imparted an interest inliberalideas to her while her mother was religious and well-read with books kept at home.[13]The family moved to Warsaw in 1873.[10]Polish andGermanwere spoken at home; Luxemburg also learnedRussian.[13]After being bed-bound with a hip problem at the age of five, she was left with a permanent limp.[14]Although over time she became fluent in Russian andFrench,Polish remained Róża's first language with German also spoken at a native level.[15][7][16]Rosa was considered intelligent early on, writing letters to her family and impressing her relatives with recitals of poetry, including the Polish classicPan Tadeusz.[9]

Rory Castle writes: "From her grandfather and father [Rosa] inherited the belief that she was a Pole first and a Jew second, her passionate opposition to Tsarism and her emotional connection to Polish language and culture. Although her parents were religious, they did not consider themselves to be Jewish by nationality, rather 'Poles of the Mosaic persuasion'".[9]He also points out that more recent research into the Luxemburg family and her early years show that "Rosa Luxemburg gained a lot more from her family than has previously been understood by her biographers. Not only in terms of her education, financial support and assistance during her frequent incarcerations, but also in terms of her identity and politics. Her family was a closely knitted support network, even when its members were spread out across Europe. This solid foundation, which supported and encouraged her at every step, gave Luxemburg the intellectual and personal confidence to go out and attempt to change the world".[9]It is especially from Luxemburg's private correspondence that it can be seen she in fact remained very close with her family throughout the years, despite being separated by borders and spread out across countries.[9]

Education and activism[edit]

In 1884, she enrolled at an all-girls'gymnasium(secondary school) in Warsaw, which she attended until 1887.[17]The Second Women's Gymnasium was a school that only rarely accepted Polish applicants and acceptance of Jewish children was even more exceptional. The children were only permitted to speak Russian.[18]At this school, Róża attended in secret circles studying the works of Polish poets and writers; officially this was forbidden due to the policy ofRussification against Polesthat was pursued in the Russian Empire at the time.[19]From 1886, Luxemburg belonged to the illegal Polish left-wingProletariat Party(founded in 1882, anticipating the Russian parties by twenty years). She began political activities by organising ageneral strike;as a result, four of the Proletariat Party leaders were put to death and the party was disbanded, though the remaining members, including Luxemburg, kept meeting in secret. In 1887, she passed hermatura(secondary schoolexaminations).

Róża became wanted by the tsarist police due to her activity in Proletariat; she hid in the countryside, working as private tutor at adworek.[20]In order to escape detention, she fled toSwitzerlandthrough the "green border" in 1889.[21]She attended theUniversity of Zurich(as did the socialistsAnatoly LunacharskyandLeo Jogiches), where she studied philosophy, history, politics, economics, zoology[22][23]and mathematics.[24]She specialised inStaatswissenschaft(political science), economic andstock exchangecrises, and theMiddle Ages.Herdoctoral dissertation"The Industrial Development ofPoland"(Die Industrielle Entwicklung Polens) was officially presented in the spring of 1897 at the University of Zurich which awarded her aDoctor of Lawdegree. Her dissertation was published by Duncker and Humblot in Leipzig in 1898. An oddity in Zurich, she was one of the first women in the world with a doctorate in political economy[21]and the first Polish woman to achieve this.[7]

In 1893, with Leo Jogiches andJulian Marchlewski(alias Julius Karski), Luxemburg founded the newspaperSprawa Robotnicza(The Workers' Cause) which opposed thenationalistpolicies of thePolish Socialist Party.Luxemburg believed that an independent Poland could arise and exist only through socialist revolutions in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia. She maintained that the struggle should be againstcapitalism,not just for Polish independence. Her position of denying a national right ofself-determinationprovoked a philosophic disagreement withVladimir Lenin.She and Leo Jogiches co-founded theSocial Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania(SDKPiL) party, after merging Congress Poland's and Lithuania's social democratic organisations. Despite living in Germany for most of her adult life, Luxemburg was the principal theoretician of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland (SDKP, later the SDKPiL) and led the party in a partnership with Jogiches, its principal organiser.[21]She remained sentimental towards Polish culture, her favourite poet wasAdam Mickiewicz,and she vehemently opposed theGermanisation of Polesin thePrussian Partition;in 1900 she published a brochure against this inPoznań.[15]Earlier, in 1893, she also wrote against the Russification of Poles by the Russian Empire's absolutist government.[16]

The 1905 revolution[edit]

After the1905 revolutionbroke out, against the advice of her Polish and German comrades, Luxemburg left for Warsaw. If she were to be recognised, tsarist authorities would imprison her, but the October/November political strike, part of theupheaval in Russiawith particularly active elements in Congress Poland, convinced Róża that she was needed in Warsaw instead of Berlin.[25]She arrived there on 30 December thanks to her German friend Anna Matschke's passport and met up with Jogiches, who had returned to Warsaw a month earlier also on a false passport; they lived together in apensionat the corner of Jasna and Świętokrzyska streets, from where they wrote for the SDKPiL's illegally published paperCzerwony Sztandar(The Red Banner).[26]Luxemburg was one of the first writers to notice the 1905 revolution's potential for democratisation within the Russian Empire. In the years 1905-1906 alone, she made in Polish and German over 100 articles, brochures, appeals, texts, and speeches about the revolution.[25]Although only the closest friends and comrades of Jogiches and Luxemburg knew of their return to the country, theOkhrana,thanks to amolerecruited by the tsarist authorities within the senior SDKPiL leadership, came to arrest them on 4 March 1906.[27]

They held her prisoner first at theratuszjail, then atPawiak prisonand later at the Tenth Pavilion of theWarsaw Citadel.Luxemburg continued to write for the SDKPiL in secret while in custody, with her works smuggled out of the compound.[27]After two officers of the Okhrana were bribed by her relatives, a temporary release on bail was secured for her on 28 June 1906 for health reasons until the court trial;[7]in early August fromSaint Petersburg,she left forKuokkala,which was then part of theGrand Duchy of Finland(an autonomous part of the Russian Empire). From there, in the middle of September, she managed to secretly flee to Germany.[27]

Germany[edit]

Luxemburg wanted to move to Germany to be at the centre of the party struggle, but she had no way of obtaining permission to remain there indefinitely. Thus, in April 1897 she married the son of an old friend, Gustav Lübeck, in order to gain German citizenship. They never lived together, and they formally divorced five years later.[28]She returned briefly toParis,then moved permanently to Berlin to supportEduard Bernstein's constitutional reform movement. Luxemburg disliked the middle-class culture of Berlin, which she considered stifling to revolution. She further dislikedPrussianmen and resented what she saw as the grip of urban capitalism onsocial democracy.[29]In theSocial Democratic Party of Germany's women's section, she metClara Zetkin,whom she made a lifelong friend. Between 1907 and his conscription in 1915, she was involved in a love affair with Clara's younger son,Kostja Zetkin,to which approximately 600 surviving letters (now mostly published) bear testimony.[30][31][32]Luxemburg was a member of the uncompromising left wing of the SPD. Their clear position was that the objectives of liberation for the industrialworking classand allminoritiescould be achieved by revolution only.

AsIrene Gammelwrites in a review of the English translation of the book inThe Globe and Mail:"The three decades covered by the 230 letters in this collection provide the context for her major contributions as a politicalactivist,socialisttheorist and writer ". Her reputation was tarnished byJoseph Stalin's cynicism inQuestions Concerning the History of Bolshevism.In his rewriting of Russian events, he placed the blame for the theory ofpermanent revolutionon Luxemburg's shoulders, with faint praise for her attacks onKarl Kautskywhich she commenced in 1910.[33]

According to Gammel, "In her controversial tome of 1913,The Accumulation of Capital,as well as through her work as a co-founder of the radicalSpartacus League,Luxemburg helped to shape Germany's young democracy by advancing an international, rather than a nationalist, outlook. This farsightedness partly explains her remarkable popularity as a socialist icon and its continued resonance in movies, novels and memorials dedicated to her life and oeuvre ". Gammel also notes that for Luxemburg" the revolution was a way of life "and yet that the letters also challenge the stereotype of" Red Rosa "as a ruthless fighter.[34]However,The Accumulation of Capitalsparked angry accusations from theCommunist Party of Germany.In 1923,Ruth FischerandArkadi Maslowdenounced the work as "errors", a derivative work of economic miscalculation known as "spontaneity".[35]

Luxemburg continued to identify as Polish and disliked living in Germany, which she saw as a political necessity, making various negative comments aboutGerman cultureduring the German Empire in her private correspondence that was written in Polish; at the same time, she loved the works ofJohann Wolfgang von Goetheand showed an appreciation forGerman literature.However, she also preferred Switzerland to Berlin and greatly missed Polish language andculture.[36][8]

Before World War I[edit]

When Luxemburg moved to Germany in May 1898, she settled in Berlin. She was active there in the left wing of the SPD in which she sharply defined the border between the views of her faction and therevisionism theoryof Eduard Bernstein. She attacked him in her brochureSocial Reform or Revolution?,released in September 1898. Luxemburg's rhetorical skill made her a leading spokesperson in denouncing the SPD'sreformistparliamentary course. She argued that the critical difference betweencapitalandlabourcould only be countered if theproletariatassumedpowerand effectedrevolutionarychanges inmethods of production.She wanted the revisionists ousted from the SPD. That did not occur, but Kautsky's leadership retained a Marxist influence on its programme.[37]

From 1900, Luxemburg published analyses of contemporary European socio-economic problems in newspapers. Foreseeing war, she vigorously attacked what she saw as Germanmilitarismandimperialism.[38]Luxemburg wanted a general strike to rouse the workers to solidarity and prevent the coming war. However, the SPD leaders refused and she broke with Kautsky in 1910. Between 1904 and 1906, she was imprisoned for her political activities on three occasions inBarnimstrasse women's prison.[39]In 1907, she went to theRussian Social Democrats' Fifth Party Day inLondon,where she met Lenin. At the socialistSecond InternationalCongress inStuttgart,herresolutiondemanding that all European workers' parties should unite in attempting to stop the war was accepted.[38]

Luxemburg taught Marxism and economics at the SPD's Berlin training centre. Her former studentFriedrich Ebertbecame the SPD leader and later theWeimar Republic's first President. In 1912, Luxemburg was the SPD representative at the European Socialists' congresses.[40]With French socialistJean Jaurès,Luxemburg argued that European workers' parties should organise a general strike when war broke out. In 1913, she told a large meeting: "If they think we are going to lift the weapons of murder against our French and other brethren, then we shall shout: 'We will not do it!'"However, when nationalist crises in theBalkanserupted into violence and then the war in 1914, there was no general strike and the SPD majority supported the war as did theFrench Socialists.TheReichstagunanimously agreed to finance the war. The SPD voted in favour of that and agreed to a truce (Burgfrieden) with the Imperial government and promised that SPD-controlledlabour unionswould refrain fromstrike actionfor the duration of the war. This led Luxemburg to contemplate suicide as the revisionism she had fought since 1899 had triumphed.[40]

In response, Luxemburg organised anti-war demonstrations inFrankfurt,calling forconscientious objectiontomilitary conscriptionand the refusal of soldiers to follow orders. On that account, she was imprisoned for a year for "inciting to disobedience against the authorities' law and order".

-

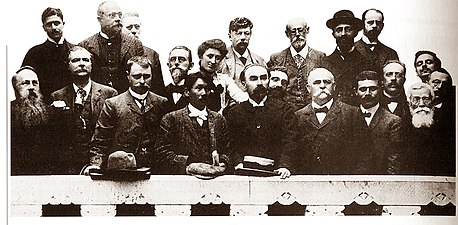

Rosa Luxemburg (centre) among attendees of theInternational Socialist Congress, Amsterdam 1904

-

Rosa Luxemburg (centre) among leaders at theInternational Socialist Congress, Amsterdam 1904

-

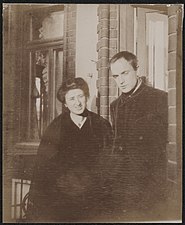

Rosa Luxemburg andLuise Kautskyin 1909

-

Rosa Luxemburg andKostja Zetkinin 1909

-

Portrait of Rosa Luxemburg in 1910

-

Clara Zetkinand Rosa Luxemburg in 1910

During the war[edit]

In August 1914, Luxemburg, along withKarl Liebknecht,Clara Zetkin,andFranz Mehring,founded the groupDie Internationale( "The International" ), which became the Spartacus League in January 1916. They wrote and distributed illegal anti-war pamphletspseudonymouslysignedSpartacus,after the slave-liberatingThraciangladiatorwho led an uprising against the Roman Republic. Luxemburg's pseudonym was Junius, afterLucius Junius Brutus,the founder of theRoman Republic.The Spartacus League vehemently rejected the SPD's support in the Reichstag for fundingthe warand urged Germany'slabor unionsto declare an anti-war general strike. As a result, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were imprisoned in June 1916 for two and a half years. During imprisonment, Luxemburg was twice relocated, first to Posen (now Poznań), then to Breslau (nowWrocław).

Luxemburg continued to write and friends secretly smuggled out and illegally published her articles. Among them wasDie Russische Revolution,criticising theBolsheviksand accusing them of seeking to impose atotalitariansingle party stateupon the Soviet Union. In that context, she wrote her famous pronouncement onfreedom of expression"Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters" ("Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden") in criticizing Lenin and the Russian Revolution.[41]She added: "The public life of countries with limited freedom is so poverty-stricken, so miserable, so rigid, so unfruitful, precisely because, through the exclusion of democracy, it cuts off the living sources of all spiritual riches and progress".[42]Another article written in April 1915 when in prison and published and distributed illegally in June 1916 originally under the pseudonymJuniuswasDie Krise der Sozialdemokratie(The Crisis of Social Democracy), also known as theJunius-BroschüreorThe Junius Pamphlet.[43]

In 1917, the Spartacus League was affiliated with theIndependent Social Democratic Party(USPD), founded byHugo Haaseand made up of anti-war former SPD members.

According to Russian historianEdvard Radzinsky,"The Bolshevik envoy in Berlin began secretly purchasing arms for the German revolutionaries. A little while ago the Germans had been assisting revolution in Russia. Now Lenin was reciprocating. The Bolshevik embassy became the headquarters of the German revolution."[44]

In November 1918, the USPD and the SPD initially shared power in theCouncil of the People's Deputies,the revolutionary government set up following the 9 Novemberabdicationof EmperorWilhelm II.[45]This took place during the early days of theGerman Revolutionthat began with theKiel mutiny,which sparked the establishment ofworkers' and soldiers' councilsacross most of Germany to put an end to World War I and to themonarchy.The SPD leaders tried to prevent the establishment of aRäterepublik(council republic) like thesovietsof the RussianRevolutions of 1905and1917by pushing for early elections to aconstituent assemblyto determine Germany's future form of government. Only a small minority of the councils supported a soviet-style system.[46]

German Revolution of 1918–1919[edit]

Luxemburg was freed from prison in Breslau on 8 November 1918, three days before thearmistice of 11 November 1918.One day later, Karl Liebknecht, who had also been freed from prison, proclaimed the Free Socialist Republic (Freie Sozialistische Republik) in Berlin.[47]He and Luxemburg reorganised the Spartacus League and foundedThe Red Flag(Die Rote Fahne) newspaper, demanding amnesty for allpolitical prisonersand the abolition ofcapital punishmentin the essayAgainst Capital Punishment.[13]On 14 December 1918, they published the new programme of the Spartacus League.

Following the arrival of Soviet emissary andmilitary advisorKarl Radek,between 29 and 31 December 1918 a joint congress of the League, independent socialists and the International Communists of Germany (IKD) took place with Radek's involvement. During the conference, Luxemburg continued to denounce theRed Terrorandcensorship in the Soviet Russia.She also accused both Lenin and the Bolsheviks of havingpolice stateaspirations. She further expressed shame that her former colleague and friend,Felix Dzerzhinsky,had agreed to head theCheka,the then Soviet security agency, and asked Radek to convey her opinions about all these matters to thePolitburoin Moscow.[48]

This same conference, however, ultimately led to the foundation on 1 January 1919 of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) under the leadership of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. Luxemburg supported the new KPD's participation in theWeimar National Assemblythat founded the Weimar Republic, but she was out-voted and the KPD boycotted the elections.[49]

Leading up to the January 1919 struggle for power with the SPD, the improvisedSpartacist Uprisingbegan in Berlin. Luxemburg spoke at the founding conference of the German Communist Party on 31 December 1918:

The progress of large-scale capitalist development during seventy years has brought us so far that today we can seriously set about destroying capitalism once and for all. No, still more; today we are not only in a position to perform this task, its performance is not only a duty toward the proletariat, but its solution offers the only means of saving human society from destruction.[50]

Like Liebknecht, Luxemburg supported the violentputschattempt.[51]In a complete reversal of her previous demands for "unrestrictedfreedom of the press",[52]The Red Flagcalled for the KPD to violently occupy the editorial offices of the anti-Spartacist press and later, all other positions of power.[51]On 8 January, Luxemburg'sRed Flagprinted a public statement by her, in which she called forrevolutionary violenceand no negotiations with the revolution's "mortal enemies", the SPD-ledRepublicanGovernment of Friedrich Ebert andPhilipp Scheidemann.[53]

Execution and aftermath[edit]

In response to the uprising, Luxemburg's former student, German Chancellor and SPD leader Ebert ordered theFreikorpsto suppress the Soviet-backed attempt at revolution, which was successfully crushed by 11 January 1919.[54]Meanwhile, Luxemburg'sRed Flagfalsely claimed that the rebellion was spreading across Germany.[55]

Luxemburg and Liebknecht were taken prisoner in Berlin on 15 January 1919 by theGuards Cavalry Rifle Divisionof theFreikorps(Garde-Kavallerie-Schützendivision).[56]The unit'sofficer commanding,CaptainWaldemar Pabst,with LieutenantHorst von Pflugk-Harttung,questioned them under torture and then, following an alleged telephone call to Defense MinisterGustav Noske,issued orders tosummarily executeboth prisoners. Luxemburg was first knocked down with a rifle butt byPrivateOtto Runge, then shot once, in the back of the head, either by LieutenantKurt Vogelor by LieutenantHermann Souchon.[57]Her body was then dumped in Berlin'sLandwehr Canal.[58]In what the militantlyantisemiticPabst later claimed was a gesture of grudging respect for his non-Jewish ancestry,[59]Liebknecht was executed byfiring squadin theTiergarten.His body, without any identification, was then dumped outside the railings of theBerlin Zoo.According to historianRobert Service:

The symbolism was intentional. The enemies of the Spartacists looked on them as being less than human. Dogs were being given a dog's death. The Spartacists leaders met their ends with courage and dignity. Of their leaders, only Thalheimer and Levi survived, and it was Levi who delivered the funeral oration for Luxemburg on 2 February. Radek went into hiding.[60]

Luxemburg's last known words written on the evening of her execution were about her belief in the masses and what she saw as the inevitability of a triumphant revolution:[61]

The contradiction between the powerful, decisive, aggressive offensive of the Berlin masses on the one hand and the indecisive, half-hearted vacillation of the Berlin leadership on the other is the mark of this latest episode. The leadership failed. But a new leadership can and must be created by the masses and from the masses. The masses are the crucial factor. They are the rock on which the ultimate victory of the revolution will be built. The masses were up to the challenge, and out of this "defeat" they have forged a link in the chain of historic defeats, which is the pride and strength of international socialism. That is why future victories will spring from this "defeat". "Order prevails in Berlin!" You foolish lackeys! Your "order" is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will "rise up again, clashing its weapons," and to your horror it will proclaim with trumpets blazing: I was, I am, I shall be!

The executions of Luxemburg and Liebknecht were the beginning of a new wave ofparamilitarywarfare in Berlin and across Germany. Thousands of members of the KPD as well as other revolutionaries and civilians were killed, often ascollateral damage.Finally, the People's Navy Division (Volksmarinedivision) and workers' and soldiers' unions, which had moved to the politicalfar left,were disbanded.[62]

The last part of the German Revolution saw many instances of armed violence and strike action throughout Germany. Significant strikes occurred in Berlin, theBremen Soviet Republic,Saxony,Saxe-Gotha,Hamburg, theRhinelandsand theRuhrregion. Last to strike was theBavarian Soviet Republicwhich was suppressed on 2 May 1919.

More than four months after the murders of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, on 1 June 1919, Luxemburg's corpse was found and identified after an autopsy at theCharitéhospital in Berlin.[56]

According to Russian historian Edvard Radzinsky, Soviet Premier Lenin retaliated for Liebknecht and Luxemburg's murder by issuing orders toGregory Zinovievfor the immediate arrest and summary execution of fourGrand Dukesfrom the recently deposedHouse of Romanov,all of whom were uncles of theNicholas II,the last Tsar. Despite the pleas ofMaxim Gorkyon behalf of one of the condemned, the known progressive and noted historianGrand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich,all four men including Mikhailovich were shot on 30 January 1919 at thePeter and Paul FortressinPetrograd.[63]The other three men executed were theGrand Duke George Mikhailovich,theGrand Duke Paul Alexandrovich,and theGrand Duke Dmitri Constantinovich.

Private Runge was sentenced to two years' imprisonment for attemptedmanslaughterand Lieutenant Vogel to two years and four months for failing to report a corpse. However, Vogel escaped after a brief period in custody, with the help ofWilhelm Canaris.Captain Pabst and Lieutenant Souchon were never prosecuted.[64]TheNazislater compensated Private Runge for having been jailed, but he died in Berlin inNKVDcustody after the end ofWorld War II.[65]The Nazis also later merged theGarde-Kavallerie-Schützendivisioninto theSA.In an interview with German news magazineDer Spiegelin 1962 and again in his memoirs, Captain Pabst alleged that Defence Minister Noske and Weimar Republic Chancellor Ebert had both covertly approved of his actions, but his account has not been confirmed, nor has his case been examined by the Parliament or Courts of Germany. In 1993, Gietinger's research on his access to the previously restricted papers of Pabst, held at the Federal Military Archives, found him as central to the planning of the murder of Luxemburg and the shielding of those who had acted under his orders from subsequent criminal prosecution.[66]

Reactions[edit]

Shortly after Luxemburg's death, her fame was alluded to byGrigory Zinovievat thePetrograd Sovieton 18 January 1919, supporting her assessment of Bolshevism.[62]

Lenin posthumously praised Luxemburg as an "eagle" of the working class, and stated that her work would serve as an example to other socialist revolutionaries.[67]

Russian revolutionaryLeon Trotskyalso publicly mourned Luxemburg's and Liebknecht's death.[68]In later years, Trotsky frequently defended Luxemburg, claiming that Joseph Stalin had vilified her.[13]In the article "Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!", Trotsky criticised Stalin for this despite what Trotsky perceived as Luxemburg's theoretical errors, writing: "Yes, Stalin has sufficient cause to hate Rosa Luxemburg. But all the more imperious therefore becomes our duty to shield Rosa's memory from Stalin's calumny that has been caught by the hired functionaries of both hemispheres, and to pass on this truly beautiful, heroic, and tragic image to the young generations of the proletariat in all its grandeur and inspirational force".[69]

Annual demonstration[edit]

In the city of Berlin aLiebknecht-Luxemburg-Demonstration,shortened toLL-Demo,is organised annually in the month of January around the date of their death. This demonstration takes place on the second weekend of the month inBerlin-Friedrichshain,starting near theFrankfurter Torand then to their graves in the central cemeteryFriedrichsfelde,also known as theGedenkstätte der Sozialisten(Socialist Memorial).[70]InEast Germany,the event was widely considered to be a mere show forSocialist Unity Party of Germanypoliticians and celebrities, which was broadcast live on state television.[71]

During thePeaceful Revolution,the annual parade inEast Berlinhonoring the deaths of Liebknecht and Luxemburg was used by East Germandissidentsas part of their campaign, "to raise their unwelcome demands at embarrassing moments for the regime". On 17 January 1988, as PremierErich Honeckerwas reviewing the parade, a group of dissidents broke through the ranks of theFree German Youthand unfurled banners bearing an infamous dictum fromDie Russische Revolution,Rosa Luxemburg's book-length denunciation of bothauthoritarian socialismandcensorship in the Soviet Union,"Freiheit ist immer Freiheit der Andersdenkenden"( "Freedom is always the freedom of dissenters" ).[41]Viewers of the parade were then subjected to the ironic sight of East GermanStasiagents beating and arresting anyone who brandished the slogan.[72]

In January 2019, the German left-wing parties commemorated the 100th anniversary of the summary execution of Luxemburg and Liebknecht.[73][74][75]

Thought[edit]

Revolutionary Socialist Democracy and Criticism of the October Revolution[edit]

Luxemburg initially professed a commitment to democracy and the necessity of revolution. Luxemburg's idea of democracy whichStanley Aronowitzcalls "generalizeddemocracy in an unarticulated form "represents Luxemburg's greatest break with" mainstream communism "since it effectively diminishes the role of thecommunist party,but it, similar to the views ofKarl Marx,states that the working class must "emancipate" themselves without a higher authority.[citation needed]

Early on, Luxemburg attacked thetotalitariantendencies present in theRussian Revolutionclaiming that without democratic institutions and protections, "life dies out in every public institution" and further claimed that such a lack of freedoms would lead to a "dictatorship of a handful of politicians".[52]

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of "justice" but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when "freedom" becomes a special privilege. [...] But socialist democracy is not something which begins only in the promised land after the foundations of socialist economy are created; it does not come as some sort of Christmas present for the worthy people who, in the interim, have loyally supported a handful of socialist dictators. Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and of the construction of socialism.

In an article published just before the October Revolution, Luxemburg characterised the RussianFebruary Revolutionof 1917 as a "revolution of the proletariat" and said that the "liberalbourgeoisie"were pushed to movement by the display of" proletarian power ". The task of the Russian proletariat, she explained, was now to end the" imperialist "world war in addition to struggling against the" imperialist bourgeoisie ". The world war made Russia ripe for asocialist revolution.Therefore, "the German proletariat are also [...] posed a question of honour, and a very fateful question".[76]However, in several works, including an essay written from jail and published posthumously by her last companionPaul Levi(publication of which precipitated his expulsion from theThird International), titledThe Russian Revolution,[77]Luxemburg sharply criticised some Bolshevik policies such as their suppression of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 following the October Revolution and their policy of supporting the purported right of all national peoples to self-determination. According to Luxemburg, the Bolsheviks' strategic mistakes created tremendous dangers for the Revolution such as its bureaucratisation. She wrote that the shortcomings of the October Revolution reflected a period of "complete failure of the international proletariat".[78]Luxemburg further stated:[79]

The awkward position that the Bolsheviks are in today, however, is, together with most of their mistakes, a consequence of basic insolubility of the problem posed to them by the international, above all the German, proletariat. To carry out the dictatorship of the proletariat and a socialist revolution in a single country surrounded by reactionary imperialist rule and in the fury of the bloodiest world war in human history – that is squaring the circle. Any socialist party would have to fail in this task and perish – whether or not it made self-renunciation the guiding star of its policies.

Bolshevik theorists such as Lenin and Trotsky responded to this criticism by arguing that Luxemburg's notions wereclassical Marxistones, but they could not be applied to Russia of 1917. They stated that the lessons of actual experience such as the confrontation with the bourgeois parties had forced them to revise the Marxian strategy. As part of this argument, it was pointed out that after Luxemburg herself got out of jail, she was also forced to confront the National Assembly in Germany, a step they compared with their own conflict with the Russian Constituent Assembly.[80]

Following her observation of the October Revolution, Luxemburg claimed that it was the "historic responsibility" of the German workers to carry out a revolution for themselves and thereby end the war.[81]When the German Revolution began, Luxemburg immediately started to agitate for a social revolution[82]which she claimed would mitigate the consequences of the Bolshevik revolution.[79]

According to Aronowitz, the vagueness of "Luxemburgian" democracy is one reason for its initial difficulty in gaining widespread support. Luxemburg herself clarified her position on democracy in her writings regarding the Russian Revolution and theSoviet Union.[citation needed]

The Accumulation of Capital[edit]

The Accumulation of Capitalwas the only work Luxemburg officially published on economics during her lifetime. In the polemic, she argued that capitalism needs to constantly expand into non-capitalist areas in order to access new supply sources, markets for surplus value and reservoirs of labour.[83]According to Luxemburg, Marx had made an error inDas Kapitalin that the proletariat could not afford to buy the commodities they produced and by his own criteria it was impossible for capitalists to make a profit in a closed-capitalist system since the demand for commodities would be too low and therefore much of the value of commodities could not be transformed into money. According to Luxemburg, capitalists sought to realise profits through offloading surplus commodities onto non-capitalist economies, hence the phenomenon of imperialism as capitalist states sought to dominate weaker economies. However, this was leading to the destruction of non-capitalist economies as they were increasingly absorbed into the capitalist system. With the destruction of non-capitalist economies, there would be no more markets to offload surplus commodities onto and capitalism would break down.[84]

The Accumulation of Capitalwas harshly criticised by both Marxist and non-Marxist economists on the grounds that her logic was circular in proclaiming the impossibility of realising profits in a close-capitalist system and that herunderconsumptionisttheory was too crude.[84]Her conclusion that the limits of the capitalist system drive it to imperialism and war led Luxemburg to a lifetime of campaigning against militarism and colonialism.[83]

Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation[edit]

TheDialectic of Spontaneity and Organisationwas the central feature of Luxemburg's political philosophy, whereinspontaneityis agrassrootsapproach to organising aclass struggle,and organisation is a top-down orvanguardistapproach to organising a class struggle. She argued that spontaneity and organisation are not separable or separate activities, but different moments of one political process as one does not exist without the other. These beliefs arose from her view that class struggle evolves from an elementary, spontaneous state to a democratic organisation.[85]Luxemburg developed theDialectic of Spontaneity and Organisationunder the influence of mass strikes in Europe, especially the Russian Revolution of 1905.[86]Unlike the social democratic orthodoxy of the Second International, she regarded the organisation of a socialist movement as a temporary means to worker enlightenment:

Social democracy is simply the embodiment of the modern proletariat's class struggle, a struggle which is driven by a consciousness of its own historic consequences. The masses are in reality their own leaders, dialectically creating their own development process. The more that social democracy develops, grows, and becomes stronger, the more the enlightened masses of workers will take their own destinies, the leadership of their movement, and the determination of its direction into their own hands.[87]

She insisted on setting the class struggle in its historical context, writing "the modern proletarian class does not carry out its struggle according to a plan set out in some book or theory; the modern workers' struggle is a part of history, a part of social progress."[88]

Legacy[edit]

Poland[edit]

In spite of her own Polish nationality and strong ties to Polish culture, her opposition to the independence of theSecond Polish Republicand later criticism from Stalinists have made her a controversial historical figure in the modernThird Polish Republic's political discourse.[6][7][8]

During thePolish People's Republic,a manufacturing facility of electric lamps in theWoladistrict of Warsaw (Polish capital and the place where Luxemburg was raised and grew up), was established and named as theZakłady Wytwórcze Lamp Elektrycznych im. Róży Luksemburg(pl).After the transformation and change of regime, the factory was privatised in 1991 and then split up into four different companies; the factory buildings were sold by 1993 and fell into disuse in 1994.[89]

A street inSzprotawaused to be named after Luxemburg (ulica Róży Luksemburg) until it was changed toulica Różana(Rose street) in September 2018.[90]Many other streets and locations in Poland either used to be or still are named after her, such as those in Warsaw,Gliwice,Będzin,Szprotawa,Lublin,Polkowice,Łódź,etc.[91][92][93][94][95]

Efforts to put up commemorative plaques in her memory have taken place in a number of Polish cities, such as Poznań and her birthplace Zamość. A 45-minute-long sightseeing tour around areas associated with the life of the Polish revolutionary was organised in Warsaw in 2019, where a statue of her by Alfred Jesion was also put on display at the Warsaw Citadel as part of the Gallery of Polish Sculpture of the 1950s.[92]

The commemorative plaque in Poznań, on the building where she lived in during May 1903, was vandalised with paint in 2013.[96]An official petition was started in 2021 to name a square in Wrocław after her, but the local government rejected the proposal.[97]

Herbarium[edit]

Luxemburg collected plant specimens from 1913 up to her death. She had a lifelong interest in botany and the natural world.[98]This was especially true when she was isolated during her imprisonments, during which time working on the herbarium was critical to her wellbeing, an escape from a harsh reality, and a connection to the outside world.[23]Holger Politt, one of the editors of the 2016 book,Rosa Luxemburg: Herbarium,[99]said, "Collecting and identifying plants helped her hold on to sanity. It was therapeutic to her; she couldn't have coped without it".[22]

Luxemburg's personal herbarium, which comprises 18 notebooks, is placed at the Archive of Modern Records in Warsaw, Poland.[98]It contains 377 different plant specimens that she collected or that were sent to her by friends and acquaintances, and are mostly of cultivated and common species.[98]Each sheet features one to three different plants, which are identified using German and Latin species names and family names, and often also have handwritten botanical descriptions, as well as the collection location and date.[98]Luxemburg collected the plants from a range of places, including theAlps,theSudety Mountains,and also in or near the prisons in Berlin,Wronki,and Wrocław (Breslau). The latter include plants from the prison vegetable garden or prison flowerbeds which she herself had planted.[98]

Germany[edit]

In 1919,Bertolt Brechtwrote the poetic memorialEpitaphhonouring Luxemburg andKurt Weillset it to music inThe Berlin Requiemin 1928:

Red Rosa now has vanished too,

And where she lies is hid from view.

She told the poor what life's about,

And so the rich have rubbed her out.

May she rest in peace.

The famous Monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, originally named Monument to the November Revolution (Revolutionsdenkmal) which was designed by pioneering modernist and laterBauhausdirectorLudwig Mies van der Roheand built in 1926 in Berlin-Lichtenberg[100]and destroyed in 1935. The memorial took the form of asuprematistcomposition of brick masses. Van der Rohe said: "As most of these people [Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and other fallen heroes of the Revolution] were shot in front of a brick wall, a brick wall would be what I would build as a monument". The commission came about through the offices ofEduard Fuchs,who showed a proposal featuringDoriccolumns and medallions of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, prompting Mies' laughter and the comment "That would be a good monument for a banker". The monument was destroyed by the Nazis after they took power.

In 1951, Liebknecht and Luxemburg were honoured with symbolic graves at theMemorial to the Socialists(German:Gedenkstätte der Sozialisten) in the Friedrichsfelde Cemetery.

In the former East Germany and East Berlin, various places were named for Luxemburg by the East German communist party. These include theRosa-Luxemburg-Platzand aU-Bahn stationwhich were located in East Berlin during theCold War.

An engraving on the nearby pavement reads "Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein" ( "I was, I am, I will be" ). TheVolksbühne(People's Theatre) is also on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz.

Following the 1989 Peaceful Revolution andGerman reunification,CDU delegates on the Berlin city council recommended renaming all streets and squares honoring Marx,August Bebel,Liebknecht, Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin. In a rare moment of agreement, bothPDSand SPD delegates balked at this and the battle became so heated that an independent commission was appointed to advise on the question. The commission ultimately recommended the compromise, "that Communists who had died too soon to help bring Weimar down, or the GDR up, should not be purged". For this reason, both streets and squares in the former East Berlin continue to bear Rosa Luxemburg's name.[101]

Dresdenhas a street and streetcar stop named after Luxemburg. The names remained unchanged after German reunification.

At the edge of theTiergartenon theKatharina-Heinroth-Uferwhich runs between the southern bank of the Landwehr Canal and the borderingZoologischer Garten(Zoological Garden), a memorial has been installed by a private initiative. On the memorial, the name Rosa Luxemburg appears in raised capital letters, marking the spot where her body was thrown into the canal byFreikorpstroops.

TheFederal Office for the Protection of the Constitutionnotes that idolisation of Luxemburg and Liebknecht remains an important tradition offar-leftextremism in theFederal Republic of Germany.[5]During the Cold War, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were idolised as martyrs by East Germany's ruling Party and continue to be idolised by its successor party:The Left.[5]

Feminists,Trotskyists, and other leftists in Germany especially show interest in Luxemburg's ideas. Distinguished modern Marxist thinkers such asErnest Mandel,who has even been characterised as Luxemburgist, have seen Luxemburg's thought as a corrective to traditional revolutionary theory.[102]In 2002, ten thousand people marched in Berlin for Luxemburg and Liebknecht and another 90,000 people laidcarnationson their graves.[103]

Russia[edit]

Opponents and critics of the far-left have often had a very different interpretation of Luxemburg's murder. Russian historian Edvard Radzinsky has gone on the record as a very harsh critic of the Soviet Government for spending so much money abroad to fund the efforts of those like Liebknecht and Luxemburg to covertly destabilise and overthrow the Weimar Republic and other Western Governments. In the Soviet Union during the same time, mass starvation was taking place, first due to Lenin's policy ofWar Communismand then to theRussian famine of 1921.According to Radzinsky, "StarvingMoscowwas feeding the Communist Parties of the whole world. People were swollen with hunger, but never mind, theworld revolutionwas at hand. "[104]Conversely, Stalin denounced Luxemburg posthumously in 1932 as a "Trotskyist".[105][106]

AsAlexander Kerenskyand the former Tsarist officer corps had fatally failed to unite for long enough to stop Lenin from seizing power in 1917,anti-communist Russian refugeesliving in the Weimar Republic occasionally expressed envy for the success of the SPD and theFreikorpsin temporarily setting aside their political differences, even for just long enough to defeat the Spartacus Uprising, which was seen as an attempted German equivalent to theBolshevik Revolution.[107]In a 1922 conversation withCount Harry Kessler,one such refugee lamented:[107]

Infamous, that fifteen thousand Russian officers should have let themselves be slaughtered by the Revolution without raising a hand in self-defense! Why didn't they act like the Germans, who killed Rosa Luxemburg in such a way that not even a smell of her has remained?

In popular culture and literature[edit]

Due to Luxemburg's importance in the development of theories ofMarxist humanistthought, the role of democracy and mass action to achieve international socialism as a pioneering advocate of workers' rights, gender equality, and as a martyr to her cause, she has become a minor iconic figure,[108][109]celebrated with references in popular culture.

- Bulgarian writerHristo Smirnenski,who praised communist ideology, wrote the poem "Rosa Luxemburg" in tribute to Luxemburg in 1923.[110]

- Rosa Luxemburg(1986),[111][112][113][114]directed byMargarethe von Trotta.The film, which starsBarbara Sukowaas Luxemburg, was the winner of the Best Actress Award at the1986 Cannes Film Festival.

- In 1992, theQuebecpainterJean-Paul Riopellerealised a fresco composed of thirty paintings entitledTribute to Rosa Luxemburg.[115][116]It is on permanent display at theNational Museum of Fine Arts of QuebecinQuebec City.

- Luxemburg influences the lives of several characters inWilliam T. Vollmann's 2005 historical fictionEurope Central.[117]

- Rosa,a novel byJonathan Rabb(2005), gives a fictional account of the events leading to Luxemburg's murder.

- The heroine in the novelBurger's Daughter(1979) byNadine Gordimeris named Rosa Burger in homage to Luxemburg.[118]

- Harry Turtledove'sSouthern Victoryseries of alternate history novels contains an American socialist politician character named Flora Hamburger, a reference to the real historical personage of Luxemburg.

- Simon Louvish's 1994 alternate history novelThe Resurrections(fromFour Walls Eight Windows,a revision ofResurrections from the Dustbin of History: A Political Fantasy), had Luxemburg and Liebknecht avoid death, their revolution becoming reality in 1923 when a failed Reichstag coup byGregor and Otto Strasser(plotted by theBlack Reichswehr'sBruno Ernst Buchrucker) killedGustav Stresemann,Wilhelm Cuno,Hans von Seecktand 17 deputies followed by the Marxists creating a Berlin commune whose squads executed the Strassers and any Nazis not already in exile, the Reichswehr then disarming theFreikorpsand accepting a German Soviet Republic's legitimacy, with Liebknecht asMinister of the Interior.[119]

- The pet tortoise atBalliol College, Oxfordwas named in honour of Luxemburg. She went missing in spring 2004.[120][121]

- A song on the 1997 albumMorskayaof the Russianrock bandMumiy Trollis titled in her honor.[122]

- Langston Hughesalludes to her death in the poem "Kids Who Die" in the line "Or the rivers where you're drowned like Liebknecht".[123]

- Luxemburg appears inKarl and Rosa,a novel byAlfred Döblin.[124]

- She also appears in the novelTime and Time AgainbyBen Elton.[125]

- Red Rosais a graphic novelisation byKate Evans.[126]

- German artist Max Beckmann in his post WWI lithograph Das Martyrium depicts Luxemburg's murder as a sexual assault, her clothes torn, her underwear revealed, one soldier fondling her left breast; another smirking while aiming his rifle butt at her right breast, the hotel manager holding her legs apart. There is no historical justification for this depiction. Tellini in Woman's Art Journal 1997 argues both the sensationalising aspect of graphic sexual assault as well as the artist'smisogynywere probably responsible.[127]

- The song Strange Time To Bloom, written byNancy Kerr,"For Rosa Luxemburg, March 1871 – January 1919" appears on the 2019 Melrose Quartet album The Rudolph Variations.[128]

- The feminist magazineLux,which began in 2020, says that it is named for Rosa Luxemburg, describing her as "one of the most creative minds to remake the socialist tradition".[129]

- Canadian authorKyo Maclearwrote in her 2017 bookBirds, Art, Life: A year of observationabout the pleasure that Luxemburg took when she was in prison from hearing and seeing birds, based on Luxemburg's letters from prison.[130]

Body identification controversy[edit]

On 29 May 2009,Spiegel online,the internet branch of the news magazineDer Spiegel,reported the recently considered possibility that someone else's remains had mistakenly been identified as Luxemburg's and buried as hers.[56]

Theforensic pathologistMichael Tsokos, head of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences at the Berlin Charité, discovered a preserved corpse lacking head, feet, or hands in the cellar of the Charité's medical history museum. He found the corpse's autopsy report suspicious and decided to perform aCT scanon the remains. The body showed signs of having been waterlogged at some point and the scans showed that it was the body of a woman of 40–50 years of age who suffered fromosteoarthritisand had legs of differing length, as Luxemburg had. A laboratory inKielalso tested the corpse usingradiocarbon datingtechniques and confirmed that it dated from the same period as Luxemburg's murder.

The originalautopsy,performed on 13 June 1919 on the body that was eventually buried atFriedrichsfelde,showed certain inconsistencies that supported Tsokos' hypothesis. The autopsy explicitly noted an absence of hip damage and stated that there was no evidence that the legs were of different lengths. Additionally, the autopsy showed no traces on the upper skull of the two blows by rifle butt inflicted upon Luxemburg. Finally, while the 1919 examiners noted a hole in the corpse's head between the left eye and ear, they did not find an exit wound or the presence of a bullet within the skull.

Assistant pathologist Paul Fraenckel appeared to doubt at the time that the corpse he had examined was Luxemburg's and in a signed addendum distanced himself from his colleague's conclusions. This addendum and the inconsistencies between the autopsy report and the known facts persuaded Tsokos to examine the remains more closely. According to eyewitnesses, when Luxemburg's body was thrown into the canal, weights were wired to her ankles and wrists. These could have slowly severed her extremities in the months her corpse spent in the water which would explain the missing hands and feet issue.[56]

Tsokos realised thatDNA testingwas the best way to confirm or deny the identity of the body as Luxemburg's. His team had initially hoped to find traces of theDNAon old postage stamps that Luxemburg had licked, but it transpired that Luxemburg had never done this, preferring to moisten stamps with a damp cloth. The examiners decided to look for a surviving blood relative and in July 2009 the German Sunday newspaperBild am Sonntagreported that a great-niece of Luxemburg had been located – a 79-year-old woman named Irene Borde. She donated strands of her hair for DNA comparison.[131]

In December 2009, Berlin authorities seized the corpse to perform an autopsy before burying it in Luxemburg's grave.[132]The Berlin Public Prosecutor's office announced in late December 2009 that while there were indications that the corpse was Luxemburg's, there was not enough evidence to provide conclusive proof. In particular, DNA extracted from the hair of Luxemburg's niece did not match that belonging to the cadaver. Tsokos had earlier said that the chances of a match were only 40%. The remains were to be buried at an undisclosed location while testing was to continue on tissue samples.[133]

Works[edit]

- The Accumulation of Capital,translated by Agnes Schwarzschild in 1951. Routledge Classics 2003 edition. Originally published asDie Akkumulation des Kapitalsin 1913.

- The Accumulation of Capital: an Anticritique,written in 1915.

- Gesammelte Werke(Collected Works), 5 volumes, Berlin, 1970–1975.

- Gesammelte Briefe(Collected Letters), 6 volumes, Berlin, 1982–1997.

- Politische Schriften(Political Writings), edited and with preface byOssip K. Flechtheim,3 volumes, Frankfurt am Main, 1966 ff.

- The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg,14 volumes, London and New York, 2011.

- The Rosa Luxemburg Reader,edited by Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson.

Writings[edit]

This is a list of selected writings:

| Writing | Year | Text | Translator | Year of English publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Industrial Development of Poland | 1898 | English | Tessa DeCarlo | 1977 |

| In Defence of Nationality | 1900 | English | Emal Ghamsharick | 2014 |

| Social Reform or Revolution? | 1900 | English | ||

| The Socialist Crisis in France | 1901 | English | ||

| Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy | 1904 | English | ||

| The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions | 1906 | English | Patrick Lavin | 1906 |

| The National Question | 1909 | English | ||

| Theory & Practice | 1910 | English | ||

| The Accumulation of Capital | 1913 | English | Agnes Schwarzschild | 1951 |

| The Accumulation of Capital: An Anti-Critique | 1915 | English | ||

| The Junius Pamphlet | 1915 | English | ||

| The Russian Revolution | 1918 | English | ||

| The Russian Tragedy | 1918 | English |

Speeches[edit]

| Speech | Year | Transcript |

|---|---|---|

| Speeches to Stuttgart Congress | 1898 | English |

| Speech to the Hanover Congress | 1899 | English |

| Speech to the Nuremberg Congress of the German Social Democratic Party | 1908 | English |

See also[edit]

- Proletarian internationalism

- Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

- List of peace activists

- Nadezhda Krupskaya

- Alexandra Kollontai

Citations[edit]

- ^Frederik Hetmann:Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben für die Freiheit,p. 308.

- ^Feigel, Lara (9 January 2019)."The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg review – tragedy and farce".The Guardian.Archived fromthe originalon 15 January 2019.Retrieved12 July2022.

- ^Christian (15 January 2023)."Cinco obras de Rosa Luxemburgo para recordar su legado"[Five works by Rosa Luxemburg to remember her legacy].Tercera Información(in Spanish).Retrieved16 January2023.

- ^Leszek Kołakowski([1981], 2008),Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. 2: The Golden Age,W. W. Norton & Company, Ch III: "Rosa Luxemburg and the Revolutionary Left".

- ^abcdGedenken an Rosa Luxemburg und Karl Liebknecht – ein Traditionselement des deutschen Linksextremismus[Commemoration of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht – a traditional element of German left-wing extremism](PDF).BfV-Themenreihe (in German). Cologne:Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.2008. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 13 December 2017.

- ^abTych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa" [Preface]. In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917[On revolution: 1905, 1917] (in Polish). Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". pp. 7–29.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^abcdeWinkler, Anna (24 June 2019)."Róża Luksemburg. Pierwsza Polka z doktoratem z ekonomii".CiekawostkiHistoryczne.pl(in Polish).Retrieved21 July2021.

- ^abcdefWinczewski, Damian (18 April 2020)."Prawdziwe oblicze Róży Luksemburg?".histmag.org.Retrieved25 July2021.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrCastle, Rory (16 June 2013)."Rosa Luxemburg, Her Family and the Origins of her Polish-Jewish Identity".praktykateoretyczna.pl.Praktyka Teoretyczna.Retrieved3 December2021.

- ^abJ. P. Nettl,Rosa Luxemburg,Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 54–55.

- ^"Glossary of People: L".Marxists.org.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^"Matrikeledition".Matrikel.uzh.ch.Archived fromthe originalon 6 February 2020.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^abcdMerrick, Beverly G. (1998)."Rosa Luxemburg: A Socialist With a Human Face".Center for Digital Discourse and Culture at Virginia Tech University.Archived fromthe originalon 2 April 2019.Retrieved18 May2015.

- ^Annette Insdorf (31 May 1987)."Rosa Luxemburg: More Than a Revolutionary".The New York Times.Retrieved6 December2008.

- ^abTych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 18.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^abLuksemburg, Róża (July 1893). "O wynaradawianiu (Z powodu dziesięciolecia rządów jen.-gub. Hurki)".Sprawa Robotnicza.

- ^Weber, Hermann;Herbst, Andreas."Luxemburg, Rosa".Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten.Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin.Retrieved16 January2019.

- ^Kautsky, Luise, ed. (2017).Rosa Luxemburg: Briefe aus dem Gefängnis: Denken und Erfahrungen der internationalen Revolutionärin.Musaicum Books. p. 55.ISBN978-80-7583-324-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 13.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". pp. 13–14.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^abcTych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 14.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^abBlixer, Rene (10 January 2019)."Rosa's secret collection".Exberliner.Retrieved2 July2023.

- ^ab"Rosa Luxemburg: A Thousand More Things".wikidata.org.Retrieved2 July2023.

- ^Zych, Marcin; Dolatowski, Jakub; Kirpluk, Izabella; Werblan-Jakubiec, Hanna (3 June 2023)."A" plant love story ": The lost (and found) private herbarium of the radical socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg".Plants People Planet.5(6): 852–858.doi:10.1002/PPP3.10396.S2CID259066901.

- ^abTych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 15.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^Tych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 16.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^abcTych, Feliks (2018). "Przedmowa". In Wielgosz, Przemysław (ed.).O rewolucji: 1905, 1917.Instytut Wydawniczy "Książka i Prasa". p. 17.ISBN978-8365304599.

- ^Waters, p. 12.

- ^Nettl, p. 383; Waters, p. 13.

- ^"Selbst im Gefängnis Trost für andere".Die Zeit.Vol. 41/1984.Die Zeit(online). 5 October 1984.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^"Heute war mir Dein süßer Brief ein solcher Trost"(PDF).Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Gesellschaftsanalyse und politische Bildung e. V., Berlin. p. 31.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Rosa Luxemburg: Gesammelte Briefe.Vol. 2, 5 and 6.

- ^Waters, p. 20.

- ^Gammel, Irene (25 March 2011)."The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, translated by George Shriver".Globe and Mail.Retrieved5 March2024.

- ^Waters, p. 19.

- ^Rauba, Ryszard (28 September 2011)."Ryszard Rauba: Wątek niemiecki w zapomnianej korespondencji Róży Luksemburg".1917.net.Instytut Politologii, Uniwersytet Zielonogórski.Retrieved25 July2021.

- ^Weitz, Eric D. (1994). "'Rosa Luxemburg Belongs to Us!'". German Communism and the Luxemburg Legacy.Central European History(27: 1), pp. 27–64.

- ^abKate Evans,Red Rosa: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg,New York, Verso, 2015

- ^Weitz, Eric D. (1997).Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State.Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- ^abPaul Frölich,Rosa Luxemburg,London: Haymarket Books, 2010

- ^ab"Frequently Asked Questions about Rosa Luxemburg - Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung".

- ^"The Russian Revolution, Chapter 6: The Problem of Dictatorship".Marxists.org. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^"Die Krise der Sozialdemokratie (Junius-Broschüre)".

- ^Edvard Radzinsky (1996),Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive Documents from Russia's Secret Archive,Anchor Books. p. 158.

- ^Altmann, Gerhard (11 April 2000)."Der Rat der Volksbeauftragten"[Council of the People's Deputies].Deutsches Historisches Museum(in German).Retrieved1 May2024.

- ^Scriba, Arnulf (15 August 2015)."Arbeiter- und Soldatenräte"[Workers' and Soldiers' Councils].Deutsches Historisches Museum(in German).Retrieved28 February2024.

- ^von Hellfeld, Matthias (16 November 2009)."Long Live the Republic – 9 November 1918".Deutsche Welle.Retrieved30 November2014.

- ^Robert Service (2012),Spies and Commissars: The Early Years of the Russian Revolution,Public Affairs Books. pp. 171–173.

- ^Luban, Ottokar (2017).The Role of the Spartacist Group after 9 November 1918 and the Formation of the KPDIn Hoffrogge, Ralf; LaPorte, Norman (eds.).Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933.London: Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 45–65.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa (2004). "Our Program and the Political Situation". In Hudis, Peter; Anderson, Kevin B. (eds.).The Rosa Luxemburg Reader.Monthly Review. p. 364.

- ^abJones 2016,p. 193.

- ^abLuxemburg, Rosa (1940) [1918]."The Problem of Dictatorship".The Russian Revolution.Translated by Wolfe, Bertram. New York: Workers Age Publishers.

- ^Jones 2016,pp. 193–194.

- ^Jones 2016,p. 210.

- ^Jones 2016,p. 203.

- ^abcdThadeusz, Frank (29 May 2009)."Revolutionary Find: Berlin Hospital May Have Found Rosa Luxemburg's Corpse".Der Spiegel.Retrieved30 November2014.

- ^"How Rosa Luxemburg Died".Daily Standard.No. 2575. Queensland, Australia. 2 April 1921. p. 3.Retrieved1 December2022– via National Library of Australia.

- ^Wroe, David (18 December 2009)."Rosa Luxemburg Murder Case Reopened".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved30 November2014.

- ^Robert S. Wistrich,From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel,University of Nebraska Press, 2012, p. 371

- ^Robert Service (2012),Spies and Commissars: The Early Years of the Russian Revolution,Public Affairs Books. p. 174.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa."Order Reigns in Berlin".Collected Works.Vol. 4. p. 536.

- ^abWaters, pp. 18–19.

- ^Edvard Radzinsky (1996),Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive Documents from Russia's Secret Archive,Anchor Books. pp. 158–159.

- ^Nettl, J. P. (1969).Rosa Luxemburg.Oxford University Press. pp. 487–490.

- ^"Martyrdom of Liebknecht and Luxemburg".Revolutionarydemocracy.org.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^Gietinger, Klaus (2019).The murder of Rosa Luxemburg.Loren Balhorn. London.ISBN978-1-78873-449-3.OCLC1089197675.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Larsen, Patrick (15 January 2009)."Ninety Years after the Murder of Rosa Luxemburg: Lessons of the Life of a Revolutionary".International Marxist Tendency.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2021.Retrieved18 May2015.

- ^Trotsky, Leon(15 January 1919)."Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg".International Marxist Tendency.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2021.Retrieved18 May2015.

- ^Trotsky, Leon(June 1932)."Hands Off Rosa Luxemburg!".International Marxist Tendency.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2021.Retrieved18 May2015.

- ^Meintz, Rene (13 January 2019)."Liebknecht-Luxemburg-Demonstration".Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg-Portal.

- ^"Luxemburg-Liebknecht-Demonstration".Jugendopposition in der DDR.

- ^David Clay Large (2000),Berlin,Basic Books. p. 520.

- ^"Gloomy German left remembers murdered Rosa Luxemburg".The Local Germany.13 January 2019.

- ^"Berlin: 15,000 Rally to Remember the 100th Anniversary of the Assassination Of Communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht".13 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^"What can we learn from Rosa Luxemburg, 100 years after her murder?".thelocal.de.15 January 2019.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Politics of Mass Strikes and Unions".Collected Works.Vol. 2. p. 245.

- ^"The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution (Rosa Luxemburg, 1918)".Libcom.org. 11 July 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2021.Retrieved16 May2021.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "On the Russian Revolution".Collected Works.Vol. 4. p. 334.

- ^abLuxemburg, Rosa (September 1918)."The Russian Tragedy".Spartacus.No. 11.Retrieved29 November2018.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "Fragment on War, National Questions, and Revolution".Collected Works.Vol. 4. p. 366.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Historic Responsibility g".Collected Works.Vol. 4. p. 374.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Beginning".Collected Works.Vol. 4. p. 397.

- ^abScott, Helen (2008). "Introduction to Rosa Luxemburg".The Essential Rosa Luxemburg: Reform or Revolution and The Mass Strike.By Luxemburg, Rosa. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p.18.ISBN978-1931859363.

- ^abKołakowski, Leszek(2008).Main Currents of Marxism.W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 407–415.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "In a Revolutionary Hour: What Next?".Collected Works.Vol. 1. p. 554.

- ^Rosa Luxemburgat theEncyclopædia Britannica

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Political Leader of the German Working Classes".Collected Works.Vol. 2. p. 280.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa. "The Politics of Mass Strikes and Unions".Collected Works.Vol. 2. p. 465.

- ^Kołakowski, Marek (23 October 2008)."Kalendarium historii polskiego przemysłu oświetleniowego".lighting.pl.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^"Szprotawa – Ulica Róży Luksemburg – ulicą Różaną".szprotawa.pl.Urząd Miejski w Szprotawie. 11 September 2018.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^"Komunikat w sprawie ul. Róży Luksemburg".bedzin.pl.Urząd Miejski w Będzinie. 19 January 2018.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^abStańczyk, Xawery (16 January 2019)."Warszawa potrzebuje Róży Luksemburg".warszawa.wyborcza.pl.Gazeta Wyborcza.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^Elżbieta, Margul; Tadeusz, Margul (15 May 1960)."Ulica Róży Luksemburg (dziś ulica Popiełuszki)".biblioteka.teatrnn.pl.Ośrodek "Brama Grodzka – Teatr NN".Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^"Dawnych bohaterów czar".polkowice.eu.Urząd Gminy Polkowice.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^"Słownik nazewnictwa miejskiego Łodzi (opracowanie autorskie) > L".log.lodz.pl.Łódzki Ośrodek Geodezji.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^AGA (5 March 2013)."Bohaterowie poznańskich ulic: Róża Luksemburg na zniszczonej tablicy".poznan.naszemiasto.pl.Polska Press Sp. z o. o.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^mk (22 April 2021)."Skwer przy ul. Kleczkowskiej we Wrocławiu nie będzie nosił imienia Róży Luksemburg".radiowroclaw.pl.Radio Wrocław.Retrieved28 May2022.

- ^abcdeZych, Marcin; Dolatowski, Jakub; Kirpluk, Izabella; Werblan-Jakubiec, Hanna (3 June 2023)."A" plant love story ": The lost (and found) private herbarium of the radical socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg".Plants, People, Planet.5(6): 852–858.doi:10.1002/ppp3.10396.ISSN2572-2611.S2CID259066901.

- ^Wittich, Evelin (1 January 2016). Politt, Holger (ed.).Rosa Luxemburg: Herbarium(in German). Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin.ISBN978-3-320-02325-6.

- ^"Mies van der Rohe".Facebook.Retrieved22 February2018.

- ^David Clay Large (2000),Berlin,Basic Books. pp. 560–561.

- ^Achacar, Gilbert."The Actuality of Ernest Mandel".

- ^"Workers World Jan. 31, 2002: Berlin events honor left-wing leaders"Archived5 November 2012 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Edvard Radzinsky (1996),Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive Documents from Russia's Secret Archive,Anchor Books. p. 182.

- ^Deutscher, Isaac (5 January 2015).The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky.Verso Books. p. 193.

- ^Nettl, J. P. (29 January 2019).Rosa Luxemburg: The Biography.Verso Books. pp. 900–1056.ISBN978-1-78873-168-3.

- ^abKessler, Harry Graf(1990).Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918–1937).New York: Grove Press. Tuesday 28 March 1922.

- ^"German corpse 'may be Luxemburg'".BCC News. 29 May 2009.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^"14 Badass Historical Women To Name Your Daughters After".BuzzFeed.13 January 2016.Retrieved26 March2018.

- ^hakki (7 October 2015)."Hristo Smirnenski Kimdir?".Hakkında Bilgi(in Turkish).Retrieved21 April2019.

- ^Die Geduld der Rosa Luxemburg (1986),retrieved30 March2019

- ^Rosa Luxemburg,10 April 1986,retrieved30 March2019

- ^"Rosa Luxemburg (Die Geduld der Rosa Luxemburg)".Independent Cinema Office.Retrieved30 March2019.

- ^Platypus Affiliated Society,Rosa Luxemburg,retrieved30 March2019

- ^"Jean-Paul Riopelle" Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg "".Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (M NBA Q).Retrieved30 March2019.

- ^Québec, Musée national des beaux-arts du."Mitchell | Riopelle – Nothing in Moderation".Newswire.ca.Retrieved30 March2019.

- ^Vollmann, William T. (2005).Europe central.New York: Viking.ISBN978-0670033928.OCLC56911959.

- ^Niedziałek, Ewe (2018)."The Desire of Nowhere – Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter in a Trans-cultural Perspective".Colloquia Humanistica(7). Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 40–41.doi:10.11649/ch.2018.003.

- ^Louvish, Simon (1994).The resurrections: a novel.Louvish, Simon. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows.ISBN978-1568580142.OCLC30158761.

- ^Balliol College, Oxford

- ^"Balliol made them".The Daily Telegraph.London. 27 April 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved27 April2010.

- ^"Morskaya (Nautical), by Mumiy Troll".Mumiy Troll.Archived fromthe originalon 10 February 2020.Retrieved21 April2019.

- ^"Langston Hughes – Kids Who Die".Genius.Retrieved21 April2019.

- ^Döblin, Alfred (1983).Karl and Rosa: a novel(1st U.S. ed.). New York: Fromm International Pub. Corp.ISBN978-0880640107.OCLC9894460.

- ^Elton, Ben (2015).Time and time again.New York.ISBN978-1250077066.OCLC898419165.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"The Radical Life of Rosa Luxemburg".The Nation.26 October 2015.Retrieved20 April2019.

- ^Tellini, Ute L. (1997). "Max Beckmann's" Tribute "to Rosa Luxemburg".Woman's Art Journal.18(2): 22–26.doi:10.2307/1358547.ISSN0270-7993.JSTOR1358547.

- ^"Melrose Quartet".Archived fromthe originalon 7 November 2019.Retrieved7 November2019.

- ^"About".

- ^Maclear, Kyo (2017).Birds, Art, Life: A year of observation(First U.S. ed.). New York.ISBN978-1501154201.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"DNA of Great-Niece May Help Identify Headless Corpse".Spiegel Online.SpiegelOnline. 21 July 2009.Retrieved21 July2009.

- ^"Berlin Authorities Seize Corpse for Pre-Burial Autopsy".Spiegel Online.SpiegelOnline. 17 December 2009.Retrieved17 December2009.

- ^"Rosa Luxemburg" floater "released for burial after 90 years".Lost in Berlin.Salon. 30 December 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 11 January 2012.

Bibliography[edit]

- Abraham, Richard (1989).Rosa Luxemburg: A Life for the International.

- Basso, Lelio (1975).Rosa Luxemburg: A Reappraisal.London.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bronner, Stephen Eric (1984).Rosa Luxemburg: A Revolutionary for Our Times.

- Cliff, Tony(1980) [1959]."Rosa Luxemburg".International Socialism(2/3). London.

- Dunayevskaya, Raya(1982).Rosa Luxemburg, Women's Liberation, and Marx's Philosophy of Revolution.New Jersey.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ettinger, Elzbieta(1988).Rosa Luxemburg: A Life.

- Frölich, Paul(1939).Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work.

- Geras, Norman(1976).The Legacy of Rosa Luxemburg.

- Gietinger, Klaus (1993).Eine Leiche im Landwehrkanal – Die Ermordung der Rosa L. (A Corpse in the Landwehrkanal – The Murder of Rosa L.)(in German). Berlin: Verlag.ISBN978-3-930278-02-2.

- Gietinger, Klaus (2019).The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg.Translated by Halborn, L. New York: Verso.ISBN978-1-78873-448-6.

- Hetmann, Frederik (1980).Rosa Luxemburg: Ein Leben für die Freiheit.Frankfurt.ISBN978-3-596-23711-1.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jones, Mark (2016).Founding Weimar: Violence and the German Revolution of 1918–1919.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-107-11512-5.

- Joffre-Eichhorn, Hjalmar Jorge (2021, ed.),Post Rosa: Letters against Barbarism.Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung: New York.

- Kemmerer, Alexandra (2016), "Editing Rosa: Luxemburg, the Revolution, and the Politics of Infantilization". European Journal of International Law, Vol. 27 (3), 853–864.doi:10.1093/ejil/chw046

- Hudis, Peter; Anderson, Kevin B., eds. (2004).The Rosa Luxemburg Reader.Monthly Review Press.