Russian colonization of North America

| Russian America Русская Америка Russkaya Amerika | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonyof theRussian Empire | |||||||||

| 1741–1867 | |||||||||

Russian Creolesettlements | |||||||||

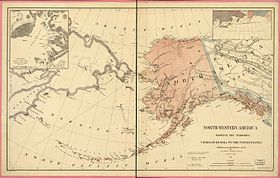

Russian possessions in North America (1835) | |||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||

| "Боже, Царя храни!" Bozhe Tsarya khrani!(1833–1867) ( "God Save the Tsar!" ) | |||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Demonym | Alaskan Creole | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| • Coordinates | 57°03′N135°19′W/ 57.050°N 135.317°W | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1799–1818 (first) | Alexander Baranov | ||||||||

• 1863–1867 (last) | Dmitry Maksutov | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 15 July 1741 | |||||||||

| 18 October 1867 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Alaska |

|---|

|

|

From 1732 to 1867, theRussian Empirelaid claim to northernPacific Coastterritories in theAmericas.Russian colonial possessions in the Americas are collectively known asRussian America(Russian:Русская Америка,romanized:Russkaya Amerika;1799 to 1867). It consisted mostly of present-dayAlaskain theUnited States,but also included the outpost ofFort RossinCalifornia,and three forts inHawaii,includingRussian Fort Elizabeth.Russian Creolesettlements were concentrated in Alaska, including the capital,New Archangel(Novo-Arkhangelsk), which is nowSitka.

Russian expansion eastwardbegan in 1552, and in 1639 Russian explorers reached thePacific Ocean.In 1725, EmperorPeter the Greatordered navigatorVitus Beringto explore the North Pacific for potential colonization. The Russians were primarily interested in the abundance of fur-bearing mammals on Alaska's coast, as stocks had been depleted byoverhunting in Siberia.Bering'sfirst voyagewas foiled by thick fog and ice, but in 1741 asecond voyageby Bering andAleksei Chirikovmade sight of the North American mainland. Bering claimed the Alaskan country for theRussian Empire.[1]Russia later confirmed its rule over the territory with theUkaseof 1799which established the southern border of Russian America along the55th parallel north.[2]The decree also provided monopolistic privileges to the state-sponsoredRussian-American Companyand established theRussian Orthodox Churchin Alaska.

Russianpromyshlenniki(trappers and hunters) quickly developed themaritime fur trade,which instigated several conflicts between theAleutsand Russians in the 1760s. The fur trade proved to be a lucrative enterprise, capturing the attention of other European nations. In response to potential competitors, the Russians extended their claims eastward from theCommander Islandsto the shores of Alaska. In 1784, with encouragement from EmpressCatherine the Great,explorerGrigory Shelekhovfounded Russia's first permanent settlement in Alaska atThree Saints Bay.Ten years later, the first group ofOrthodox Christianmissionaries began to arrive, evangelizing thousands of Native Americans, many of whose descendants continue to maintain the religion.[3]By the late 1780s, trade relations had opened with theTlingits,and in 1799 theRussian-American Company(RAC) was formed in order to monopolize the fur trade, also serving as an imperialist vehicle for theRussificationofAlaska Natives.

Angered by encroachment on their land and other grievances, the indigenous peoples' relations with the Russians deteriorated. In 1802, Tlingit warriors destroyed several Russian settlements, most notablyRedoubt Saint Michael(Old Sitka), leavingNew Russiaas the only remaining outpost on mainland Alaska. This failed to expel the Russians, who re-established their presence two years later following theBattle of Sitka.(Peace negotiations between the Russians and Native Americans would later establish amodus vivendi,a situation that, with few interruptions, lasted for the duration of Russian presence in Alaska.) In 1808, Redoubt Saint Michael was rebuilt asNew Archangeland became the capital of Russian America after the previous colonial headquarters were moved fromKodiak.A year later, the RAC began expanding its operations to more abundantsea ottergrounds inNorthern California,whereFort Rosswas built in 1812.

By the middle of the 19th century, profits from Russia's North American colonies were in steep decline. Competition with the BritishHudson's Bay Companyhad brought the sea otter to near extinction, while the population of bears, wolves, and foxes on land was also nearing depletion. Faced with the reality of periodic Native American revolts, the political ramifications of theCrimean War,and unable to fully colonize the Americas to their satisfaction, the Russians concluded that their North American colonies were too expensive to retain. Eager to release themselves of the burden, the Russians sold Fort Ross in 1841, and in 1867, after less than a month of negotiations, theUnited Statesaccepted EmperorAlexander II's offer to sell Alaska. TheAlaska Purchasefor $7.2 million (equivalent to $157 million in 2023) ended Imperial Russia's colonial presence in the Americas.

Exploration[edit]

The earliest written accounts indicate that the Eurasian Russians were the first Europeans to reach Alaska. There is an unofficial assumption that EurasianSlavicnavigators reached the coast of Alaska long before the 18th century.

In 1648,Semyon Dezhnevsailed from the mouth of theKolyma Riverthrough theArctic Oceanand around the eastern tip of Asia to theAnadyr River.One legend holds that some of his boats were carried off course and reached Alaska. However, no evidence of settlement survives. Dezhnev's discovery was never forwarded to the central government, leaving open the question of whether or notSiberiawas connected to North America.[4]

The first sighting of the Alaskan coastline was in 1732; this sighting was made by the Russian maritime explorer and navigatorIvan Fedorovfrom sea near present-dayCape Prince of Waleson the eastern boundary of theBering Straitopposite RussianCape Dezhnev.He did not land.

The first landfall happened in southernAlaskain 1741 during the Russian exploration byVitus BeringandAleksei Chirikov.In the early 1720s, TsarPeter the Greatcalled for another expedition. As a part of the 1733–1743Second Kamchatka expedition,theSv. Petrunder the DaneVitus Beringand theSv. Pavelunder the RussianAlexei Chirikovset sail from theKamchatkanport ofPetropavlovskin June 1741. They were soon separated, but each continued sailing east.[5]On July 15, Chirikov sighted land, probably the west side ofPrince of Wales Islandin southeast Alaska.[6]He sent a group of men ashore in a longboat, making them the first Europeans to land on the northwestern coast of North America. On roughly July 16, Bering and the crew ofSv. PetrsightedMount Saint Eliason the Alaskan mainland; they turned westward toward Russia soon afterward. Meanwhile, Chirikov and theSv. Pavelheaded back to Russia in October with news of the land they had found. In November, Bering's ship was wrecked onBering Island.There Bering fell ill and died, and high winds dashed theSv. Petrto pieces. After the stranded crew wintered on the island, the survivors built a boat from the wreckage and set sail for Russia in August 1742. Bering's crew reached the shore of Kamchatka in 1742, carrying word of the expedition. The high quality of thesea otterpelts they brought sparked Russian settlement in Alaska.

Due to the distance from central authority in St. Petersburg, and combined with the difficult geography and lack of adequate resources, the next state-sponsored expedition would wait more than two decades until 1766, when captains Pyotr Krenitsyn and Mikhail Levashov embarked for theAleutian Islands,eventually reaching their destination after initially been wrecked onBering Island.Between 1774 and 1800Spainalso ledseveral expeditions to Alaskain order to assert its claim over the Pacific Northwest. These claims were later abandoned at the turn of the 19th century following the aftermath of theNootka Crisis.CountNikolay RumyantsevfundedRussia's first naval circumnavigationunder the joint command ofAdam Johann von KrusensternandNikolai Rezanovin 1803–1806, and was instrumental in the outfitting of the voyage of theRiurik's circumnavigation of 1814–1816, which provided substantial scientific information on Alaska's and California's flora and fauna, and important ethnographic information on Alaskan and Californian (among other) natives.

Trading company[edit]

Imperial Russia was unique among European empires for having no state sponsorship of foreign expeditions or territorial (conquest) settlement. The first state-protectedtrading companyfor sponsoring such activities in the Americas was theShelikhov-Golikov CompanyofGrigory ShelikhovandIvan Larionovich Golikov.A number of other companies were operating inRussian Americaduring the 1780s. Shelikhov petitioned the government for exclusive control, but in 1788Catherine IIdecided to grant his company a monopoly only over the area it had already occupied. Other traders were free to compete elsewhere. Catherine's decision was issued as the imperialukase(proclamation) of September 28, 1788.[7]

The Shelikhov-Golikov Company formed the basis for theRussian-American Company(RAC). Its charter was laid out in a 1799, by the newTsarPaul I,which granted the company monopolistic control over trade in theAleutian Islandsand the North America mainland, south to55° north latitude.[5]: 102 The RAC was Russia's firstjoint stock company,and came under the direct authority of the Ministry of Commerce of Imperial Russia. Siberian merchants based inIrkutskwere initial major stockholders, but soon replaced by Russia's nobility and aristocracy based inSaint Petersburg.The company constructed settlements in what is today Alaska,Hawaii,[8]andCalifornia.

Russian colonization[edit]

1740s to 1800[edit]

Beginning in 1743, small associations offur-tradersbegan to sail from the shores of the Russian Pacific coast to theAleutian islands.[9]

Rather than hunting the marine life themselves, the Sibero-Russianpromyshlennikiforced theAleutsto do the work for them, often by taking hostage family members in exchange for hunted seal-furs.[10]This pattern ofcolonial exploitationresembled some of thepromyshlennikipractices in their expansionintoSiberiaand theRussian Far East.[11] As word spread of the potential riches in furs, competition among Russian companies increased and a large number of Aleuts were apparentlyenserfed.[12][10][13][14]

As the animal populations declined, the Aleuts, already too dependent on the newbarter-economyfostered by the Russian fur-trade, were increasingly coerced into taking greater and greater risks in the highly dangerous waters of theNorth Pacificto hunt for more otter.[citation needed]As theShelekhov-Golikov Companyof 1783-1799 developed a monopoly, its use of skirmishes and violent incidents turned into systematic violence as a tool of colonial exploitation of the indigenous people. When the Aleutian serfs revolted and won some victories, thepromyshlennikiretaliated, killing many and destroying their boats and hunting gear, leaving them no means of survival.[citation needed]The most devastating effects came from disease: during the first two generations (1741-1759 & 1781-1799) of Sibero-Russianpromyshlennikicontact, 80 percent of the Aleut population died from Eurasianinfectious diseases;these were by then endemic among Eurasians, but the Aleuts had noimmunityagainst the diseases.[15]

Though the Alaskancolonywas never very profitable because of the costs of transportation, most Russian traders were determined to keep the land for themselves. In 1784,Grigory Ivanovich Shelekhov,who later set up theRussian-American Company[16][better source needed] that developed into the Alaskan colonial administration, arrived inThree Saints BayonKodiak Islandwith two ships, theThree Saints(Russian:Три Святителя) and theSt. Simon.[17]The KoniagAlaska Nativesharassed the Russian party and Shelekhov responded by killing hundreds and taking hostages to enforce the obedience of the rest. Having established his authority on Kodiak Island, Shelekhov founded the second permanent Russian settlement in Alaska (afterUnalaska,permanently settled since 1774) on the island's Three Saints Bay.[citation needed]

In 1790, Shelekhov, back in Russia, hiredAlexander Andreyevich Baranovto manage his Alaskan fur-enterprise. Baranov moved the colony to the northeast end of Kodiak Island, wheretimberwas available. The site later developed as what is now the city ofKodiak.Russian colonists took Koniag wives and started families whose surnames continue today, such as Panamaroff, Petrikoff, and Kvasnikoff.[citation needed]In 1795 Baranov, concerned by the sight of non-Russian Europeans trading with the natives in southeast Alaska, established Mikhailovsk six miles (10 km) north of present-daySitka.[citation needed]He bought the land from theTlingit,but in 1802, while Baranov was away, Tlingit from a neighboring settlement attacked and destroyed Mikhailovsk. Baranov returned with a Russian warship and razed the Tlingit village. He built the settlement of New Archangel (Russian:Ново-Архангельск,romanized:Novo-Arkhangelsk) on the ruins of Mikhailovsk.[citation needed]It became the capital of Russian America – and later the city of Sitka.[citation needed]

As Baranov secured the Russians' settlements in Alaska, the Shelekhov family continued to work among the topleadersto win amonopolyon Alaska's fur trade.[citation needed]In 1799 Shelekhov's son-in-law,Nikolay Petrovich Rezanov,had acquired a monopoly on the American fur trade from EmperorPaul I.Rezanov formed theRussian-American Company.As part of the deal, theEmperorexpected the company to establish new settlements in Alaska and to carry out an expanded colonization program.[citation needed]

1800 to 1867[edit]

By 1804, Baranov, now manager of the Russian–American Company, had consolidated the company's hold on fur trade activities in the Americas following his suppression of the Tlingit clan at theBattle of Sitka.The Russians never fully colonized Alaska. For the most part, they clung to the coast and shunned the interior.[citation needed]

From 1812 to 1841, the Russians operatedFort Ross, California.From 1814 to 1817,Russian Fort Elizabethwas operating in theKingdom of Hawaii.By the 1830s, the Russian monopoly on trade was weakening. The BritishHudson's Bay Companywas leased the southern edge of Russian America in 1839 under theRAC-HBC Agreement,establishingFort Stikinewhich began siphoning off trade.[citation needed]

A company ship visited the Russian American outposts only every two or three years to give provisions.[18]Because of the limited stock of supplies, trading was incidental compared to trapping operations under the Aleutian laborers.[18]This left the Russian outposts dependent upon British andAmericanmerchants for sorely needed food and materials; in such a situation Baranov knew that the RAC establishments "could not exist without trading with foreigners."[18]Ties with Americans were particularly advantageous since they could sell furs atGuangzhou,closed to the Russians at the time. The downside was that American hunters andtrappersencroached on territory Russians considered theirs.[citation needed]

Starting with the destruction of thePhoenixin 1799, several RAC ships sank or were damaged in storms, leaving the RAC outposts with scant resources. On June 24, 1800, an American vessel sailed to Kodiak Island. Baranov negotiated the sale of over 12,000 rubles worth of goods carried on the ship, averting "imminent starvation."[19]During his tenure Baranov traded over 2 million rubles worth of furs for American supplies, to the consternation of the board of directors.[18]From 1806 to 1818 Baranov shipped 15 million rubles worth of furs to Russia, only receiving under 3 million rubles in provisions, barely half of the expenses spent solely on the Saint Petersburg company office.[18]

TheRusso-American Treaty of 1824recognized exclusive Russian rights to thefur tradenorth of latitude 54°40'N, with the American rights and claims restricted to below that line. This division was repeated in theTreaty of Saint Petersburg,a parallel agreement with the British in 1825 (which also settled most of the border withBritish North America). However, the agreements soon went by the wayside, and with the retirement ofAlexandr Baranovin 1818, the Russian hold on Alaska was further weakened.

When the Russian-American Company'scharterwas renewed in 1821, it stipulated that the chief managers from then on be navalofficers.Most naval officers did not have any experience in the fur trade, so the company suffered. The second charter also tried to cut off all contact withforeigners,especially the competitive Americans. This strategy backfired since the Russian colony had become used to relying on American supply ships, and the United States had become a valued customer for furs. Eventually the Russian–American Company entered into an agreement with the Hudson's Bay Company, which gave the British rights to sail through Russian territory.[citation needed]

Colonies[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

The first Russiancolonyin Alaska was founded in 1784 byGrigory Shelikhov.[5]: 102 Subsequently, Russian explorers and settlers continued to establish trading posts in mainland Alaska, on theAleutian Islands,Hawaii,[citation needed]andNorthern California.

Alaska[edit]

TheRussian-American Companywas formed in 1799 with the influence ofNikolay Rezanovfor the purpose of huntingsea ottersfor their fur.[5]: 40 The peak population of the Russian colonies was about 4,000 although almost all of these wereAleuts,Tlingitsand otherNative Alaskans.The number of Russians rarely exceeded 500 at any one time.[5]: xiii

California[edit]

The Russians established an outpost calledFortress Ross(Russian:Крѣпость Россъ,Krepost' Ross) in 1812 nearBodega BayinNorthern California,[5]: 181 north ofSan Francisco Bay. The Fort Ross colony included a sealing station on theFarallon Islandsoff San Francisco.[20] By 1818 Fort Ross had a population of 128, consisting of 26 Russians and of 102 Native Americans.[5]: 181 The Russians maintained it until 1841, when they left the region.[21]As of 2015[update]Fort Ross is a FederalNational Historical Landmarkon theNational Register of Historic Places.It is preserved—restored in California'sFort Ross State Historic Park,about 80 miles (130 km) northwest of San Francisco.[22]

Spanish concern about Russian colonial intrusion prompted the authorities inNew Spainto initiate[when?]the upperLas CaliforniasProvince settlement, withpresidios(forts),pueblos(villages), and theCalifornia missions.After declaring their independence in 1821, the Mexicans also asserted themselves in opposition to the Russians: theMission San Francisco de Solano(Sonoma Mission, 1823) specifically responded to the presence of the Russians at Fort Ross; and Mexico established theEl Presidio Real de Sonomaor Sonoma Barracks in 1836, with GeneralMariano Guadalupe Vallejoas the Commandant of the Northern Frontier of theAlta CaliforniaProvince. The fort was the northernmost Mexican outpost to halt any further Russian settlement southward.[citation needed]The restored Presidio and mission are in the present-day city ofSonoma, California.

In 1920 a one-hundred-poundbronze church bell was unearthed in an orange grove nearMission San Fernando Rey de Españain theSan Fernando ValleyofSouthern California.It has an inscription in theRussian language(translated here): "In the tear 1796, in the month of January, this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak by the blessing ofJuvenaly of Alaska,during the sojourn ofAlexander Andreyevich Baranov."[citation needed]How thisRussian OrthodoxKodiakchurch artifact fromKodiak IslandinAlaskaarrived at aRoman Catholic MissionChurch inSouthern Californiaremains unknown.

Missionary activity[edit]

At Three Saints Bay, Shelekov built a school to teach the natives to read and writeRussian,and introduced the first resident missionaries and clergymen who spread theRussian Orthodoxfaith. This faith (with its liturgies and texts, translated into Aleut at a very early stage) had been informally introduced, in the 1740s–1780s. Some fur traders founded local families or symbolically adopted Aleut trade partners as godchildren to gain their loyalty through this special personal bond. The missionaries soon opposed the exploitation of the indigenous populations, and their reports provide evidence of the violence exercised to establish colonial rule in this period.

The RAC's monopoly was continued by EmperorAlexander Iin 1821, on the condition that the company would financially support missionary efforts.[23]The company board ordered chief managerArvid Adolf Etholénto builda residencyinNew Archangelfor bishopVeniaminov[23]When aLutheran churchwas planned for theFinnishpopulation of New Archangel, Veniamiov prohibited any Lutheran priests from proselytizing to neighboring Tlingits.[23]Veniamiov faced difficulties in exercising influence over the Tlingit people outside New Archangel, due to their political independence from the RAC leaving them less receptive to Russian cultural influences than Aleuts.[23][24]A smallpox epidemic spread throughout Alaska in 1835-1837 and the medical aid given by Veniamiov created converts to Orthodoxy.[24]

Inspired by the same pastoral theology asBartolomé de las CasasorSt. Francis Xavier,the origins of which were in early Christianity's need to adapt to the cultures ofClassical antiquity,missionaries in Russian America applied a strategy that placed value on local cultures and encouraged indigenous leadership in parish life and missionary activity. When compared to later Protestant missionaries, the Orthodox policies "in retrospect proved to be relatively sensitive to indigenous Alaskan cultures."[23]This cultural policy was originally intended to gain the loyalty of the indigenous populations by establishing the authority of Church and State as protectors of over 10,000 inhabitants of Russian America. (The number of ethnic Russian settlers had always been less than the record 812, almost all concentrated in Sitka and Kodiak).

Difficulties arose in training Russian priests to attain fluency in any of the various Indigenous Alaskan languages. To redress this, Veniaminov opened a seminary for mixed race and native candidates for the Church in 1845.[23]Promising students were sent to additional schools in eitherSaint PetersburgorIrkutsk,the later city becoming the original seminary's new location in 1858.[23]The Holy Synod instructed for the opening of four missionary schools in 1841, to be located inAmlia,Chiniak,Kenai,andNushagak.[23]Veniamiov established the curriculum, which included Russian history, literacy, mathematics, and religious studies.[23]

A side effect of the missionary strategy was the development of a new and autonomous form of indigenous identity. Many native traditions survived within local "Russian" Orthodox tradition and in the religious life of the villages. Part of this modern indigenous identity is an Alpha bet and the basis for written literature in nearly all of the ethnic-linguistic groups in the Southern half of Alaska. Father Ivan Veniaminov (later St.Innocent of Alaska), famous throughout Russian America, developed an Aleutdictionaryfor hundreds of language and dialect words based on theRussian Alpha bet.

The most visible trace of the Russian colonial period in contemporary Alaska is the nearly 90 Russian Orthodox parishes with a membership of over 20,000 men, women, and children, almost exclusively indigenous people. These include severalAthabascangroups of the interior, very largeYup'ikcommunities, and quite nearly all of the Aleut and Alutiiq populations. Among the few Tlingit Orthodox parishes, the large group inJuneauadoptedOrthodox Christianity only after the Russian colonial period, in an area where there had been no Russian settlers nor missionaries. The widespread and continuing local Russian Orthodox practices are likely the result of thesyncretismof local beliefs with Christianity.

In contrast, the SpanishRoman Catholiccolonial intentions, methods, and consequences in California and the Southwest were the product of theLaws of Burgosand theIndian Reductionsof conversions and relocations tomissions;while more force and coercion was used, the indigenous peoples likewise created a kind of Christianity that reflected many of their traditions.

Observers noted that while their religious ties were tenuous, before the sale of Alaska there were 400 native converts to Orthodoxy in New Archangel.[24]Tlingit practitioners declined in number after the lapse of Russian rule, until there were only 117 practitioners in 1882 residing in the place, by then renamed asSitka.[24]

Russian settlements in North America[edit]

- Alaska

- Unalaska, Alaska– 1774

- Three Saints Bay,Alaska– 1784

- Fort St. George inKasilof, Alaska– 1786

- St. Paul, Alaska– 1788

- Fort St. Nicholas inKenai, Alaska– 1791

- Pavlovskaya, Alaska(now Kodiak) – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island, Alaska – 1793

- Fort onHinchinbrook Island,Alaska – 1793

- New Russianear present-dayYakutat, Alaska– 1796

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael, Alaskanear Sitka – 1799

- Novo-Arkhangelsk, Alaska(now Sitka) – 1804

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk atBristol Bay,Alaska – 1819

- Redoubt St. Michael, Alaska– 1833

- Nulato, Alaska– 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysiusin present-dayWrangell, Alaska(now Fort Stikine) – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission, Alaska– 1837

- Kolmakov Redoubt, Alaska – 1844

- California

- Fort Ross, California– 1812

- Hawaiʻi

- Fort Elizabethnear Waimea,Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi– 1817

- Fort Alexandernear Hanalei, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi – 1817

Purchase of Alaska[edit]

By the 1860s, the Russian government was ready to abandon its Russian America colony. Over-hunting had severely reduced the fur-bearing animal population, and competition from the British and Americans exacerbated the situation. This, combined with the difficulties of supplying and protecting such a distant colony, reduced interest in the territory. In addition, Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing Russian Alaska without compensation in some future conflict, especially to the British. The Russians believed that in a dispute with Britain, their hard-to-defend region might become a prime target for British aggression fromBritish Columbia,and would be easily captured. So following the Union victory in theAmerican Civil War,TsarAlexander IIinstructed the Russian minister to the United States,Eduard de Stoeckl,to enter into negotiations with theUnited States Secretary of StateWilliam H. Sewardin the beginning of March 1867. At the instigation of Seward theUnited States Senateapproved the purchase, known as theAlaska Purchase,from theRussian Empire.The cost was set at 2 cents an acre, which came to a total of $7,200,000 on April 9, 1867. The canceled check is in the present dayUnited States National Archives.

After Russian America was sold to the US in 1867, for $7.2 million (2 cents per acre, equivalent to $156,960,000 in 2023), all the holdings of the Russian–American Company were liquidated.

Following the transfer, many elders of the localTlingittribe maintained that "Castle Hill"comprised the only land that Russia was entitled to sell. Other indigenous groups also argued that they had never given up their land; the Americans had encroached on it and taken it over. Native land claims were not fully addressed until the latter half of the 20th century, with the signing by Congress and leaders of theAlaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

At the height of Russian America, the Russian population had reached 700, compared to 40,000 Aleuts. They and theCreoles,who had been guaranteed the privileges of citizens in the United States, were given the opportunity of becoming citizens within a three-year period, but few decided to exercise that option. GeneralJefferson C. Davisordered the Russians out of their homes in Sitka, maintaining that the dwellings were needed for the Americans. The Russians complained of rowdiness of and assaults by the American troops. Many Russians returned to Russia, while others migrated to thePacific NorthwestandCalifornia.

Legacy[edit]

TheSoviet Union(USSR) released aseries of commemorative coinsin 1990 and 1991 to mark the 250th anniversary of the first sighting of and claiming domain overAlaska–Russian America.The commemoration consisted of asilver coin,aplatinum coin,and twopalladium coinsin both years.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a resurgence of Russian ultra-nationalism has spurred regret and recrimination over the sale of Alaska to the United States.[25][26][27]There are periodicmass mediastories in theRussian FederationthatAlaskawas not sold to the United States in the 1867Alaska Purchase,but only leased for 99 years (= to 1966), or 150 years (= to 2017)—and would be returned to Russia.[28]During thewar in Ukraine,such statements reappeared in Russian media. Those claims of illegitimacy derive from wrong or misleading interpretations of a policy of the Russian Federation to re-acquire formerly held properties.[29]The Alaska Purchase Treaty is absolutely clear that the agreement was for a complete Russiancessionof the territory.[30][31]Not the purchase from the Russian Empire, but the legitimacy of colonial rule altogether has been an issue of theAlaskan Nativepeoples in their struggle to democracy andindigenous rights.[32]

Russian settlements in North America[edit]

- Unalaska, Alaska– 1774

- Three Saints Bay,Alaska– 1784

- Fort St. George inKasilof, Alaska– 1786[citation needed]

- St. Paul, Alaska– 1788

- Fort St. Nicholas inKenai, Alaska– 1791[citation needed]

- Pavlovskaya, Alaska(now Kodiak) – 1791

- Fort Saints Constantine and Helen on Nuchek Island, Alaska – 1793[citation needed]

- Fort onHinchinbrook Island,Alaska – 1793[citation needed]

- New Russianear present-dayYakutat, Alaska– 1796

- Redoubt St. Archangel Michael, Alaskanear Sitka – 1799

- Novo-Arkhangelsk, Alaska(now Sitka) – 1804

- Fort Ross, California– 1812

- Fort Elizabethnear Waimea,Kaua'i, Hawai'i– 1817

- Fort Alexandernear Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817

- Fort Barclay-de-Tolly near Hanalei, Kaua'i, Hawai'i – 1817[citation needed]

- Fort (New) Alexandrovsk atBristol Bay,Alaska – 1819[citation needed]

- Kolmakov Redoubt, Alaska– 1832

- Redoubt St. Michael, Alaska– 1833

- Nulato, Alaska– 1834

- Redoubt St. Dionysiusin present-dayWrangell, Alaska(now Fort Stikine) – 1834

- Pokrovskaya Mission, Alaska– 1837

- Ninilchik, Alaska– 1847

See also[edit]

Native Americans

Russians

- List of Russian explorers

- Herman of Alaska

- Mikhail Tebenkov

- Johan Hampus Furuhjelm

- Nikolai Rezanov

- Vitus Bering

History

- Russian Colonialism

- Territorial evolution of Russia

- Great Northern Expedition

- California Fur Rush

- Awa'uq Massacre

- Russo-American Treaty of 1824

- History of the west coast of North America

Other topics

References[edit]

- ^Charles P. Wohlforth (2011).Alaska For Dummies.John Wiley & Sons. p. 18.

- ^United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland,"Text of Ukase of 1779"inBehring Sea Arbitration(London: Harrison and Sons, 1893), pp. 25-27

- ^Sergei, Kan (2014).Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity Through Two Centuries.Seattle:University of Washington Press.ISBN9780295805344.OCLC901270092.

- ^Campbell, Robert (2007).In Darkest Alaska: Travel and Empire Along the Inside Passage.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 1.ISBN978-0-8122-4021-4.

- ^abcdefgBlack, Lydia T. (2004).Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867.Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- ^""The People You May Visit"".Russia's Great Voyages.California Academy of Sciences. Archived fromthe originalon April 13, 2003.RetrievedSeptember 23,2005.

- ^Pethick, Derek (1976).First Approaches to the Northwest Coast.Vancouver: J.J. Douglas. pp. 26–33.ISBN0-88894-056-4.

- ^"Russian Fort".National Historic Landmark summary listing.National Park Service. Archived fromthe originalon October 18, 2007.RetrievedJuly 4,2008.

- ^Compare:Isto, Sarah Crawford (2012)."Chapter One: The Russian Period 1749-1866".The Fur Farms of Alaska: Two Centuries of History and a Forgotten Stampede.Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. p. 8.ISBN978-1-60223-171-9.

Russian merchants along the route from Kamchatka to Kiakhta must have been elated when Vitus Bering's expedition returned in 1742 to report that the northern coast of America was nearby and that its waters teemed with fur seals and sea otters. By the following year, the first commercial vessel had already been constructed in Kamchatka and had set off for a two-year voyage to the Aleutians. [...] A rush of fur-seeking expeditions followed

- ^abCarpenter, Roger M. (2015)."Times Are Altered with Us": American Indians from First Contact to the New Republic.Wiley Blackwell. pp. 231–232.ISBN978-1-118-73315-8.

- ^

Etkind, Alexander (2011).Internal Colonization: Russia's Imperial Experience.Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons (published 2013). p. 68.ISBN9780745673547.

Agreeing withSolovievthat the history of Russia was the history of colonization,Shchapovdescribed the process.... Two methods of colonization were primary: 'fur colonization,' with hunters harvesting and depleting the habitats of fur animals and moving further and further across Siberia all the way to Alaska; and 'fishing colonization,' which supplied Russian centers with fresh- or salt-water fish and caviar.

- ^Stephen W. Haycox, Mary Childers Mangusso (2011).An Alaska Anthology: Interpreting the Past.University of Washington Press. p. 27.

- ^

Compare:

Grinëv, Andrei Val'terovic (2016). "Russian Promyshlenniki in Alaska at the end of the Eighteenth Century".Russian Colonization of Alaska: Preconditions, Discovery, and Initial Development, 1741-1799[Predposylki rossiisoi kolonizatsii Alyaski, ee otkrytie i pervonachal'noye osnovanie]. Translated by Bland, Richard L. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press (published 2018). p. 198.ISBN9781496210852.

The Aleuts and other dependent Natives of the Russian colonies could never be considered slaves, or feudal serfs, or civilian workers in the usual sense of the terms.... Up to the 1790s the Natives were obligated to pay tribute to the royal treasury, demonstrating personal dependence on the Russian emperor. Some of the Natives, evidently making up from a twelfth to an eighth of the adult population, belonged to the so-called kayury, whose position was in fact that of slaves, since they received nothing for their labor besides scanty clothing and food. However, this was not slavery as once existed in ancient Rome or in the American South....

- ^Compare:Gwenn, Miller (December 15, 2015). "Introduction".Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America.Ithaca: Cornell University (published 2010). p. 2.ISBN978-1-5017-0069-9.

The people of Kodiak kept some slaves,kalgi,outsiders whom they acquired through trading and warfare with people from other areas.

- ^"Aleut History".The Aleut Corporation.Archived fromthe originalon November 2, 2007.

- ^

Mathews-Benham, Sandra K. (March 10, 2008). "5: From the Aleutian Chain to Northern California".American Indians in the Early West.Cultures in the American West. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO (published 2008). p. 246.ISBN9781851098248.

... before he died, Shelikhov had appointed Alexandr Baranov as governor of the Russian Alaska Company, the first functional and approved Russian monopoly in Alaska.

- ^"Alaska History Timeline".Kodiakisland.net.Archived fromthe originalon October 27, 2005.RetrievedAugust 31,2005.

- ^abcdeWheeler, Mary E. (1971). "Empires in Conflict and Cooperation: The" Bostonians "and the Russian-American Company".Pacific Historical Review.40(4): 419–441.doi:10.2307/3637703.JSTOR3637703.

- ^Tikhmenev, P. A. (1978). Pierce, Richard A.; Donnelly, Alton S. (eds.).A History of the Russia-American Company.Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp.63–64.ISBN9780295955643.

- ^ Schoenherr, Allan A.;Feldmeth, C. Robert (1999).Natural History of the Islands of California.California natural history guides. Vol. 61. University of California Press. p. 375.ISBN9780520211971.RetrievedApril 27,2015.

- ^"Fort Ross Cultural History Fort Ross Interpretive Association".fortrossinterpretive.org.Archived fromthe originalon May 28, 2010.RetrievedJanuary 15,2022.

- ^"Fort Ross SHP".

- ^abcdefghiNordlander, David (1995). "Innokentii Veniaminov and the Expansion of Orthodoxy in Russian America".Pacific Historical Review.64(1): 19–35.doi:10.2307/3640333.JSTOR3640333.

- ^abcdKan, Sergei (1985). "Russian Orthodox Brotherhoods among the Tlingit: Missionary Goals and Native Response".Ethnohistory.32(3): 196–222.doi:10.2307/481921.JSTOR481921.

- ^Nelson, Soraya Sarhaddi (April 1, 2014)."Not An April Fools' Joke: Russians Petition To Get Alaska Back".NPR.RetrievedNovember 26,2019.

- ^Tetrault-Farber, Gabrielle (March 31, 2014)."After Crimea, Russians Say They Want Alaska Back".The Moscow Times.RetrievedNovember 26,2019.

- ^Gershkovich, Evan (March 30, 2017)."150 Years After Sale of Alaska, Some Russians Have Second Thoughts".The New York Times.RetrievedNovember 26,2019.

- ^Haycox, Steve (May 18, 2017)."Russian extremists want Alaska back".Anchorage Daily News.RetrievedNovember 26,2019.

- ^Stepanova, Alexandra (January 31, 2024)."Analysis: Russian decree on its assets overseas (no, Alaska was not mentioned)".annie lab.RetrievedMay 22,2024.

- ^Metcalfe, Peter (August 24, 2017)."The Purchase of Alaska: 1867 or 1971".Alaska Historical Society - Dedicated to the promotion of Alaska history by the exchange of ideas and information.RetrievedMay 22,2024.

- ^"Transcription of the English text of the Alaska Treaty of Cession".Our Documents.The United States National Archives.RetrievedNovember 26,2019.

- ^"There Are Two Versions of the Story of How the U.S. Purchased Alaska From Russia".Smithsonian Magazine.Smithsonian Institution.March 29, 2017.RetrievedMay 22,2024.

Further reading[edit]

- Black, Lydia T.(2004).Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867.Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.ISBN978-1-889963-05-1.

- Black, Lydia T.;Dauenhauer, Nora;Dauenhauer, Richard(2008).Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804.University of Washington Press.ISBN978-0-295-98601-2.

- Essig, Edward Oliver.Fort Ross: California Outpost of Russian Alaska, 1812–1841(Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1991.)

- Frost, Orcutt (2003).Bering: The Russian Discovery of America.New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-10059-4.

- Gibson, James R. "Old Russia in the New World: adversaries and adversities in Russian America." inEuropean Settlement and Development in North America(University of Toronto Press, 2019) pp. 46–65.

- Gibson, James R.Imperial Russia in frontier America: the changing geography of supply of Russian America, 1784–1867(Oxford University Press, 1976)

- Gibson, James R. "Russian America in 1821."Oregon Historical Quarterly(1976): 174–188.online

- Grinev, Andrei Valterovich (2008).The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741–1867.Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0-8032-2071-3.

- Grinëv, Andrei Val’terovich. "The External Threat to Russian America: Myth and Reality."Journal of Slavic Military Studies30.2 (2017): 266–289.

- Grinëv, Andrei Val’terovich.Russian Colonization of Alaska: Preconditions, Discovery, and Initial Development, 1741–1799Translated by Richard L. Bland. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.ISBN978-1-4962-0762-3.online review

- Kobtzeff, Oleg (1985).La Colonization russe en Amérique du Nord: 18 - 19 ème siècles[Russian Colonization in North America, 18th-19th Centuries] (in French). Paris: thesis, University of Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne (available in limited editions in specialized libraries).

- Miller, Gwenn A. (2010).Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0-8014-4642-9.

- Oleksa, Michael J.(1992).Orthodox Alaska: A Theology of Mission.Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press.ISBN978-0-88141-092-1.

- Oleksa, Michael J., ed. (2010).Alaskan Missionary Spirituality(2nd ed.). Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press.ISBN978-0-88141-340-3.

- Pierce, Richard A.Russian America, 1741–1867: A Biographical Dictionary(Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1990)

- Starr, S. Frederick,ed. (1987).Russia's American Colony.Durham, NC: Duke University Press.ISBN978-0-8223-0688-7.

- Saul, Norman E. "Empire Maker: Aleksandr Baranov and Russian Colonial Expansion into Alaska and Northern California."Journal of American Ethnic History36.3 (2017): 91–93.

- Saul, Norman. "California-Alaska trade, 1851–1867: The American Russian commercial company and the Russian America company and the sale/purchase of Alaska."Journal of Russian American Studies2.1 (2018): 1–14.online

- Vinkovetsky, Ilya (2011).Russian America: An Overseas Colony of a Continental Empire, 1804–1867.New York, NY: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-539128-2.

Natives[edit]

- Grinëv, Andrei V. "Natives and Creoles of Alaska in the maritime service in Russian America."The Historian82.3 (2020): 328–345.online[dead link]

- The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741–1867,Andreĭ Valʹterovich Grinev (GoogleBooks)

- Luehrmann, Sonja.Alutiiq villages under Russian and US rule(University of Alaska Press, 2008.)

- Smith-Peter, Susan (2013). ""A Class of People Admitted to the Better Ranks": The First Generation of Creoles in Russian America, 1810s–1820s ".Ethnohistory.60(3): 363–384.doi:10.1215/00141801-2140758.

- Savelev, Ivan. "Patterns in the Adoption of Russian Linguistic and National Traditions by Alaskan Natives."International Conference on European Multilingualism: Shaping Sustainable Educational and Social Environment EMSSESE, 2019.(Atlantis Press, 2019).online

Primary sources[edit]

- Gibson, James R. (1972). "Russian America in 1833: The Survey of Kirill Khlebnikov".The Pacific Northwest Quarterly.63(1): 1–13.JSTOR40488966.

- Golovin, Pavel Nikolaevich, Basil Dmytryshyn, and E. A. P. Crownhart-Vaughan.The end of Russian America: Captain PN Golovin's last report, 1862(Oregon Historical Society Press, 1979.)

- Khlebnikov, Kyrill T.Colonial Russian America: Kyrill T. Khlebnikov's Reports, 1817–1832(Oregon Historical Society, 1976)

- baron Wrangel, Ferdinand Petrovich.Russian America: Statistical and ethnographic information(Kingston, Ont.: Limestone Press, 1980)

Historiography[edit]

- Grinëv, Andrei. V.; Bland, Richard L. (2010)."A Brief Survey of the Russian Historiography of Russian America of Recent Years"(PDF).Pacific Historical Review.79(2): 265–278.doi:10.1525/phr.2010.79.2.265.JSTOR10.1525/phr.2010.79.2.265.[permanent dead link]

External links[edit]

- States and territories established in 1741

- States and territories disestablished in 1867

- Russian America

- Colonial United States (Russian)

- Colonization history of the United States

- European colonization of North America

- Subdivisions of the Russian Empire

- Fur trade

- Pre-Confederation British Columbia

- History of Yukon

- Pre-statehood history of Alaska

- Pre-statehood history of California

- History of European colonialism

- Overseas empires

- Russian exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Territorial evolution of Russia