SOLRAD 2

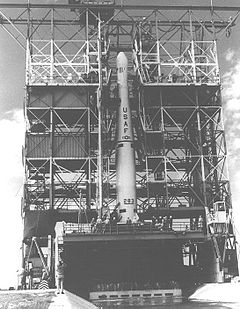

SOLRAD reserve satellite (similar to SOLRAD 2) | |

| Names | GRAB (2) SOLar RADiation 2 SR 2 GREB (2) |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Solar X-rays |

| Operator | Naval Research Laboratory(USNRL) |

| COSPAR ID | 1960-F16 (SRD-2) |

| Mission duration | Failed to orbit |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | SOLRAD |

| Manufacturer | Naval Research Laboratory(USNRL) |

| Launch mass | 18 kg (40 lb) |

| Dimensions | 51 cm (20 in) of diameter |

| Power | 6 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 30 November 1960, 19:50GMT |

| Rocket | Thor-Ablestar |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral,LC-17B |

| Contractor | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| End of mission | |

| Destroyed | Failed to orbit |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit(planned) |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 930 km (580 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 930 km (580 mi) |

| Inclination | 66.70° |

| Period | 100.0 minutes |

SOLRAD (SOLar RADiation) 2was the public designation for a combination surveillance andsolar X-raysandultravioletscientific satellite, the second in theSOLRADprogram developed by theUnited States Navy'sNaval Research Laboratory.The SOLRAD scientific package aboard the satellite provided cover for theGRAB(Galactic Radiation and Background)electronic surveillancepackage, the mission of which was to map theSoviet Union's air defense radar network.

SOLRAD 2 was launched along withTransit 3Aatop aThor-Ablestarrocket on 30 November 1960, but both satellites failed to reach orbit when the booster flew off course and was destroyed, raining debris overCuba,which prompted official protests from the Cuban government. As a result, future SOLRAD flights were programmed to avoid a Cuban flyover during launch.

Background

[edit]

In 1957, theSoviet Unionbegan deploying theS-75 Dvinasurface-to-air missile,controlled byFan Songfire control radars. This development made penetration of Soviet air space by American bombers more dangerous. TheU.S. Air Forcebegan a program of cataloging the rough location and individual operating frequencies of these radars, using electronic reconnaissance aircraft flying off the borders of the Soviet Union. This program provided information on radars on the periphery of the Soviet Union, but information on the sites further inland was lacking. Some experiments were carried out using radio telescopes looking for serendipitous Soviet radar reflections off theMoon,but this proved an inadequate solution to the problem.[2]: 362

In March 1958,[3]: 4 while theNaval Research Laboratory(NRL) was heavily involved inProject Vanguard,theU.S. Navy's effort to launch a satellite, NRL engineer Reid D. Mayo, determined that a Vanguard derivative could be used to map Soviet missile sites. Mayo had previously developed a system for submarines whereby they could evade anti-submarine aircraft by picking up their radar signals. Physically small and mechanically robust, it could be adapted to fit inside the small Vanguard frame.[2]: 364

Mayo presented the idea to Howard Lorenzen, head of the NRL's countermeasures branch. Lorenzen promoted the idea within theU.S. Department of Defense(DoD), and six months later the concept was approved under the name "Tattletale".[2]: 364 President Eisenhowerapproved full development of the program on 24 August 1959.[3]: 4

After a news leak byThe New York Times,Eisenhower cancelled the project. The project was restarted under the name "Walnut" (the satellite component given the name "DYNO".[1]: 140, 151 ) after heightened security had been implemented, including greater oversight and restriction of access to "need-to-know"personnel.[4]: 2 American space launches were not classified at the time,[5][6]and a co-flying cover mission that would share space with DYNO was desired to conceal DYNO's electronic surveillance mission from its intended targets.[7]: 300

The study of the Sun'selectromagnetic spectrumprovided an ideal cover opportunity. The U.S. Navy had wanted to determine the role of solar flares in radio communications disruptions[7]: 300 and the level of hazard to satellites and astronauts posed by ultraviolet and X-ray radiation.[8]: 76 Such a study had not previously been possible as the Earth's atmosphere blocks the Sun's X-ray and ultraviolet output from ground observation. Moreover, solar output is unpredictable and fluctuates rapidly, making sub-orbitalsounding rocketsinadequate for the observation task. A satellite was required for long-term, continuous study of the complete solar spectrum.[9]: 5–6, 63–65 [10]

The NRL already had a purpose-built solar observatory in the form ofVanguard 3,which had been launched in 1959. Vanguard 3 had carried X-ray and ultraviolet detectors, though they had been completely saturated by the background radiation of theVan Allen belts.[9]: 63 Development of the DYNO satellite from the Vanguard design was managed by NRL engineer Martin Votaw, leading a team of Project Vanguard engineers and scientists who had not migrated toNASA.[11]The dual-purpose satellite was renamed GRAB ( "Galactic Radiation And Background" ), sometimes referred to as GREB ( "Galactic Radiation Experiment Background" ), and referred to in its scientific capacity as SOLRAD ( "SOLar RADiation" ).[1]: 142, 149 [7]: 300

A dummymass simulatorSOLRAD was successfully launched on 13 April 1960, attached to aTransit 1B,[7]: 301 proving the dual satellite launch technique.[12]On 5 May 1960, just four days afterthe downingofGary Powers'U-2flight over theSoviet Unionhighlighted the vulnerability of aircraft-based surveillance, President Eisenhower approved the launch of an operational SOLRAD satellite.[13]: 32 SOLRAD/GRAB 1was launched into orbit on 22 June 1960, becoming both the world's first surveillance satellite and the first satellite to observe the Sun in X-ray and ultraviolet light.[7]

Spacecraft

[edit]

SOLRAD 2 was roughly a duplicate of its predecessor, SOLRAD/GRAB 1,[14]spherical and 51 cm (20 in) in diameter,[8]slightly lighter than SOLRAD/GRAB 1 despite carrying the same scientific experiments (18 kg (40 lb) versus 19.05 kg (42.0 lb)),[4]and powered by six circular patches ofsolar cells.[4]: a1-4 The solar cells powered nineD cellbatteries in series (12voltstotal)[4]: 10 providing 6wattsof power.[13]: 32

The satellite's SOLRAD scientific package included twoLyman- Alphaphotometers(nitric oxideion chambers) for the study of ultraviolet light in the 1,050–1,350Åwavelength range and one X-ray photometer (anargonion chamber) in the 2–8 Å wavelength range, all mounted around the equator of the satellite.[15]As with SOLRAD 1, permanent magnets were installed to deflect charged particles from the detector windows to address the saturation issue that had impacted theVanguard 3mission.[9]: 64–65

The satellite's GRAB surveillance equipment was designed to detect Soviet air defense radars broadcasting on theS-band(1,550–3,900MHz),[13]: 29, 32 over a circular area 6,500 km (4,000 mi) in diameter beneath it.[1]: 108 A receiver in the satellite was tuned to the approximate frequency of the radars, and its output was used to trigger a separateVery high frequency(VHF) transmitter in the spacecraft. As it traveled over the Soviet Union, the satellite would detect the pulses from the missile radars and immediately re-broadcast them to American ground stations within range, which would record the signals and send them to the NRL for analysis. Although GRAB's receiver was omnidirectional, by looking for the same signals on multiple passes and comparing that to the known location of the satellite, the rough location of the radars could be determined, along with their exactpulse repetition frequency.[3]: 4–7 [1]: 108

Telemetrywas sent via fourwhip-style63.5 cm (25.0 in) long antennas mounted on SOLRAD's equator.[8]: 76 Scientific telemetry was sent on 108 MHz,[8]: 78 theInternational Geophysical Yearstandard frequency used by Vanguard.[16]: 84, 185 Commands from the ground and electronic surveillance were collected via smaller antennas on 139 MHz.[3]: 7 Data received on the ground was recorded on magnetic tape and couriered back to the NRL, where it was evaluated, duplicated, and forwarded to theNational Security Agency(NSA) atArmy Fort Meade,Maryland,and theStrategic Air Command(SAC) atOffut Air Force BaseOmaha,Nebraska,for analysis and processing.[17]

Like most early automatic spacecraft, SOLRAD 2, though spin stabilized,[7]: 300 lacked activeattitude controlsystems and thus scanned the whole sky without focusing on a particular source.[9]: 13 So that scientists could properly interpret the source of the X-rays detected by SOLRAD 2, the spacecraft carried a vacuum photocell to determine when the Sun was striking its photometers and the angle at which sunlight hit them.[9]: 64

Mission

[edit]

In November 1960, Votaw and his 14-man team drove the technical components for the SOLRAD 2 launch (loaded in the trunks of their own cars) from NRL headquarters inWashington, D.C.toCape Canaveral,flying having been ruled out due to the recent rash of skyjackings toCuba.Upon arrival, the NRL team set up a temporary ground station in a hangar on the Cape's west side. SOLRAD 2's booster (first stageThorNo. 283 and second stage Able-Star 006) was erected nearly three miles away atCape Canaveral Pad LC-17B.[18]

On launch day, 30 November 1960, minor glitches caused so many holds in the hours-long countdown that the NRL team commissioned a betting pool as to when the launch would occur.[18]Nevertheless, SOLRAD 2 did launch, along withTransit 3A(a separate satellite on the same rocket), at 19:50 GMT,[12]into a sunny sky. The Thor first stage shut down prematurely (it had been scheduled to burn for 163 seconds). Out of caution, despite the possibility that its payload could still be orbited, the now separated first and second stages of the booster were destroyed by therange safety officer.[18]

Like SOLRAD 1 (but no other American launches to date), SOLRAD 2's course to orbit took it over theCaribbean islandofCuba.[19]As a result of the rocket's destruction, fragments fell over Cuba'sOriente Provinceat the eastern end of the island, northwest of the U.S. Navy'sGuantanamo Bay base.TheCuban Armypost atHolguínreported fragments falling along a 200 sq mi (518 km2) swath and reported recovering "two complete sphere [sic], two apparatuses in the form of cones and various cylinders" with English inscriptions. One piece of recovered debris was described as a "sealed sphere of some 40 pounds". Given thatVanguard TV-3's satellite survived a booster explosion, it is possible that this was SOLRAD 2, recovered intact. The items were then delivered to army headquarters atPalma Soriano.According to a 1988 Chinese document, some of the recovered debris was sold to thePeople's Republic of Chinaand used in aid of the design of the second stage of theCSS-4intercontinental ballistic missile(ICBM).[18]

The Cuban government protested the incident:Revolución,an official Cuban newspaper, accused the United States of "Yankee provocation", and government radio stations denounced what they described as efforts to destroyCastro'sregime. Cuba lodged an official complaint with theUnited Nations.In response to these protests, American launches overflying Cuba were postponed, improvements were made to the range-safety system at Cape Canaveral,[18]and future SOLRAD flights were programmed to follow a more northerly course to orbit during launch that did not overfly Cuba.[20]

Legacy

[edit]The SOLRAD/GRAB series flew three more times finishing with theSOLRAD 4Bmission launched 26 April 1962. Of the five SOLRAD/GRAB missions, only SOLRAD/GRAB 1 andSOLRAD 3/GRAB 2were successes, the others failing to reach orbit. In 1962, all U.S. overhead reconnaissance projects were consolidated under theNational Reconnaissance Office(NRO), which elected to continue and expand the GRAB mission starting July 1962[1]with a next-generation set of satellites, code-namedPOPPY.[4]With the initiation of POPPY, SOLRAD experiments would no longer be carried on electronic spy satellites; rather, they would now get their own satellites, launched alongside POPPY missions to provide some measure of mission cover.[12]Starting withSOLRAD 8,launched in November 1965, the final five SOLRAD satellites were scientific satellites launched singly, three of which were also given NASAExplorer programnumbers. The last in this final series of SOLRAD satellites flew in 1976. In all, there were thirteen operational satellites in the SOLRAD series.[7]The GRAB program was declassified in 1998.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdef"Review and Redaction Guide"(PDF).National Reconnaissance Office. 2008.Retrieved15 February2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^abcBamford, James (2007).Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency.Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.ISBN978-0-307-42505-8.

- ^abcdMcDonald, Robert A.; Moreno, Sharon K."GRAB and POPPY: America's Early ELINT Satellites"(PDF).National Reconnaissance Office.Retrieved11 February2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^abcde"History of the Poppy Satellite System"(PDF).National Reconnaissance Office. 14 August 2006.Retrieved28 February2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Day, Dwayne A.; Logsdon, John M.; Latell, Brian (1998).Eye in the Sky: The Story of the Corona Spy Satellites.Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. p.176.ISBN978-1-56098-830-4.

- ^"Space Science and Exploration".Collier's Encyclopedia.Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. 1964. p. 356.OCLC1032873498.

- ^abcdefgAmerican Astronautical Society (23 August 2010).Space Exploration and Humanity: A Historical Encyclopedia, in 2 volumes.Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.ISBN978-1-85109-519-3.

- ^abcd""Bonus" Payload Set for Transit 2A Orbit ".Aviation Week and Space Technology.McGraw Hill Publishing Company. 20 June 1960.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2019.Retrieved8 January2019.

- ^abcdeSignificant Achievements in Solar Physics 1958–1964.NASA. 1966.OCLC860060668.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Committee on the Navy's Needs in Space for Providing Future Capabilities, Naval Studies Board, Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences, National Research Council of the National Academies (2005)."Appendix A: Department of the Navy History in Space".Navy's Needs in Space for Providing Future Capabilities.The National Academies Press. p. 157.doi:10.17226/11299.ISBN978-0-309-18120-4.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2019.Retrieved6 January2019.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Parry, Daniel (2 October 2011)."NRL Center for Space Technology Reaches Century Mark in Orbiting Spacecraft Launches".U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2019.Retrieved12 January2019.

- ^abcMcDowell, Jonathan."Launch Log".Jonathon's Space Report.Archivedfrom the original on 1 December 2008.Retrieved30 December2018.

- ^abc"NRO Lifts Veil On First Sigint Mission".Aviation Week and Space Technology.McGraw Hill Publishing Company. 22 June 1998.Retrieved6 March2019.

- ^"Transit IIIA Planned for November 29 launch".Aviation Week and Space Technology.McGraw Hill Publishing Company. 7 November 1960.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2019.Retrieved10 January2019.

- ^"SOLRAD 1".NASA. 14 May 2020.Retrieved15 January2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Green, Constance and Lomask, Milton (1970).Vanguard – A History.NASA.ISBN978-1-97353-209-5.SP-4202.Archivedfrom the original on 3 March 2016.Retrieved28 April2019.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"GRAB, Galactic Radiation And Background, World's First Reconnaissance Satellite".Naval Research Laboratory. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2007.Retrieved14 April2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^abcde"The Navy's Spy Missions in Space".U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. April 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2019.Retrieved21 April2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"Cubans Claim U.S. Rocket His Near 3rd Largest City".The Logan Daily News.Associated Press. 1 December 1960. p. 1.Retrieved18 May2019– via Newspapers.

- ^abLePage, Andrew (30 September 2014)."Vintage Micro: The First ELINT Satellites".Drew Ex Machina.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2019.Retrieved18 January2019.