SSEtruria

45°28′59″N83°28′25″W/ 45.483017°N 83.473663°W

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Etruria |

| Operator | Hawgood Transit Company[2] |

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | West Bay City Shipbuilding Company[2] |

| Yard number | 604[2] |

| Launched | February 8, 1902[3][1] |

| In service | 1902[2] |

| Out of service | June 18, 1905[2] |

| Identification | U.S. Registry #136977[2] |

| Fate | Rammed by the steamerAmasa StoneonLake Huron[2] |

| Wreck discovered | May 17, 2011 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Lake freighter |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 50 feet (15 m)[2] |

| Depth | 28 feet (8.5 m)[2] |

| Installed power | 2 ×Scotch marine boilers |

| Propulsion | 1500-horsepowertriple expansion steam engine |

| Capacity | 7000 tons |

| Notes | Largest ship lost on the Great Lakes at the time of sinking |

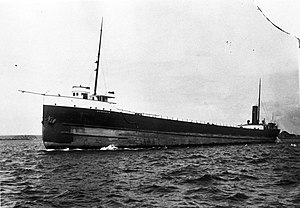

SSEtruriawas a steel hulledlake freighterthat served on theGreat LakesofNorth Americafrom her construction in 1902 to her sinking in 1905. On June 18, 1905, while sailing upbound onLake Huronwith a cargo ofcoal,she was rammed and sunk by the freighterAmasa Stone10 miles (16 km) offPresque Isle Light.[2]For nearly 106 years the location ofEtruria'swreck remained unknown, until the spring of 2011 when her wreck was found upside down in 310 feet (94 m) of water.[4]

History[edit]

Design and construction[edit]

Etruriawas named after the famousCunard Lineocean liner,RMSEtruria.Etruriawas built by theWest Bay City Shipbuilding CompanyinWest Bay City, Michiganfor the Hawgood Transit Company ofCleveland, Ohio.She had anoverall lengthof 434 feet (132 m), and abetween perpendiculars lengthof 414 feet (126 m).[3]Her beam was 50 feet (15 m) wide, and in her original enrollment, her depth was listed as 24 feet (7.3 m); also, in her original enrollment, hergross register tonnagewas listed at 4744 tons and hernet register tonnagewas listed at 4439 tons.[2][4][5]She was powered by a 1500-horsepowertriple expansion steam engine,which was fueled by twoScotch marine boilers.She had a cargo capacity of 7000 tons. She was also built with a single deck, and twelve cargo hatches.[1][3][6]

Etruriawas the first of four identical sister ships built for the Hawgood Transit Company. Her sisters were (in order of construction),Bransford,J.M. JenksandH.B. Hawgood.[7][8][9][10]

Service history[edit]

Etruriawas launched on February 8, 1902 as hull number #604.[1][3]She was enrolled for the first time on April 12, 1905 inPort Huron, Michigan,and was given the official number #136977. On April 15, 1902Etruriawas re-enrolled in Cleveland, Ohio. On March 25, 1903 an error inEtruria'senrollment was corrected; her depth was corrected from 24 feet (7.3 m) to 28 feet (8.5 m); and her gross tonnage was corrected from 4744 tons to 4653 tons, and her net tonnage was corrected from 4439 tons to 3415 tons.[3][5][2]

Final voyage[edit]

On June 18, 1905 while upbound with a cargo of coal fromToledo, Ohio,heading toSuperior, Wisconsin,Etruriawas rammed by the larger steel freighterAmasa Stoneon her starboard side, abreast of her No.9 hatch.[2][11][12]After just five minutes,Etruriarolled over and sank about 10 miles (16 km) offPresque Isle Light;her entire crew was rescued by the steamerMaritana.[3][1][6][4]

At the time of her sinking,Etruriawas the largest freighter ever to have sunk on the Great Lakes.[1]

Etruria'senrollment surrendered on June 30, 1905.[2][3]

Aftermath[edit]

Shortly afterEtruria'ssinking, the Hawgood Transit Company and the Mesaba Steamship Company (owners ofAmasa Stone) filed several lawsuits against each other for the damage done to their respective vessels. TheUnited States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuitrendered a final judgement on June 15, 1908.[1]A brief by the Hawgood Transit Company stated that:

The steamerEtruriawas laden with 7,000 net tons of coal loaded on Lake Erie and destined forLake Michiganports. At all times theEtruriawas properly crewed and fully manned.[1]About 01:00 hours on June 18, 1905, the hazy night turned to rain and fog set in, and theEtruriaproceeded at a moderate pace, sounding her fog signal regularly.[1]About 03:35 hours that morning on a proper course headed for theStraits of Mackinac,theEtruriaheard the fog signals of a steamer, which proved to be theAmasa Stone.[1]It sounded a long distance from theEtruriaand was distinctly to her starboard. At this point, theEtruriablew a two-blast signal but theStonedidn’t reply with the same passing signal, and theEtruriaslowed to bare steerage, stopped her engine completely and shortly thereafter, without warning or signal, theStonecame out of the fog at full speed. TheStonestruck theEtruriaa heavy blow on her starboard side abreast hatch No.9, breaking in her side.[1]TheEtruriabegan to list and sank at once, meanwhile blowing distress signals. TheEtrurialaunched its lifeboats just in time to see the steamer roll over. As it turned upside down, the hatches gave way, and the coal cargo spilled out before the sinking ship. TheAmasa Stonethen departed the scene without rendering assistance. The steamerMaritanawas upbound in the vicinity and picked up the crew, landing them atDetourand at theSault.[1]

The lawsuit stated thatEtruriahad a value of $265,000, her cargo had a value of $13,460.70 and the crew's effects had a value of $3,029.11; in total,Etruriawas a $281,489.81 loss. The suit further stated that the collision was "due solely to the negligence and want of care on the part ofAmasa Stoneand those in charge of navigation ".[1]Amasa Stonewas found to be guilty of the following actions:[1]

- Not maintaining an efficient lookout

- Not answering passing signals

- Running at excessive speed

- Failing to stop and reverse

- Failing to stand by

Lawyers for the Mesaba Steamship Company concluded thatEtruriawas not travelling at a slow speed, but at a fast one and that her navigational officers were guilty of inattention.[1]They also concluded thatAmasa Stonedid not leave the scene following the collision, but that she turned round, and tried to offer assistance, butEtruria'screw took to the lifeboats, and rowed off in the opposite direction.[1]When both sides made their argument,JudgeHenry Harrison Swanruled inDetroit, Michiganthat both vessels were equally at fault, and that insurance proceeds were the only means of recouping each vessel's loss.[1][13][14]

Etruriawreck[edit]

Discovery[edit]

In 2011 a group consisting of expert shipwreck hunters and high school students fromSaginaw, Michigantried to locate the long sought-after semi-whaleback steamerChoctaw.[1]Their search effort was made into a documentary named "Project Shiphunt", which was sponsored bySonyandIntel.[15][1][16]On May 17, 2011 they discovered two shipwrecks,Etruriaand the schoonerM.F. Merrickwhich sank in 1889 after a collision with the steamerR.P. Ranney.[17][18][1][16]

Etruriatoday[edit]

The remains ofEtruriarest in 310 feet (94 m) of cold fresh water. The wreck is upside down, with 405 feet (123 m) of her hull exposed, with a portion of her stern being buried.[1]Her bow is raised above the sediment by several feet allowing access to her intact pilot house and forward deck house area and first cargo hatch.[1]Her forward ladder is in place running to the port side bridge wing, which is buried in sediment. Her twostocklessanchorsare still intact at her bow. Discovery of the wrecks was made public on July 13, 2011.[16][1]Her wreck is part of theThunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

National Register of Historic Places nomination[edit]

On September 19, 2014 the wreck ofEtruriawas nominated for a listing on theNational Register of Historic Places,for her state level significance.[1][19]Her listing was denied; had she been listed, she would have been given the reference number #14001009.[20][21][22]

See also[edit]

- List of shipwrecks in the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

- List of shipwrecks on the Great Lakes

- List of Great Lakes shipwrecks on the National Register of Historic Places

References[edit]

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx"Etruria Shipwreck Site National Register of Historic Places Registration Form"(PDF).National Park Service.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2015-03-25.RetrievedNovember 24,2019.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopq"Etruria".Bowling Green State University.RetrievedNovember 24,2019.

- ^abcdefgh"Etruria".Great Lakes Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry.RetrievedNovember 24,2019.

- ^abc"Etruria".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.RetrievedNovember 24,2019.

- ^ab"Etruria".Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library.RetrievedNovember 27,2019.

- ^ab"SS Etruria (+1905)".Wrecksite.RetrievedNovember 30,2019.

- ^"Bransford".Great Lakes Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry.RetrievedNovember 27,2019.

- ^"J.M. Jenks".Great Lakes Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry.RetrievedNovember 30,2019.

- ^"H.B. Hawgood".Great Lakes Vessel Histories of Sterling Berry.RetrievedNovember 30,2019.

- ^"Etruria & Bransford: Fateful Futures"(PDF).Lake Huron Lore.RetrievedNovember 30,2019.

- ^James Donahue."Steamer Etruria Sunk by a Stone".RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Etruria (Propeller), U136977, sunk by collision, 18 Jun 1905".Maritime History of the Great Lakes.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"The Ford's Lost Sister".Great Lakes Steamship Society.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Etruria".Here's The Thing.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Long-lost shipwrecks found in Lake Huron".NBC News.14 July 2011.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^abc"Project Shiphunt".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Project Shiphunt full documentary".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Five high school students, along with an expedition leader, find two shipwrecks in Lake Huron".Michigan Radio.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"Push ahead to raise more shipwrecks onto the National Register of Historic Places".Great Lakes Echo.6 October 2014.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"National Register of Historic Places 2014 Pending Lists"(PDF).National Park Service.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"4 shipwrecks nominated to National Register of Historic Places".True Radio North.3 October 2014.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^"National Resister of Historic Places: Weekly List 20141219".National Park Service.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-01-12.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Greenwood, John Orville (April 1998).The fleets of Cleveland-Cliffs, Detroit and Cleveland Navigation, Traverse City Transportation and the Hawgood family.Freshwater Press.ISBN978-0-912514-57-4.

- Greenwood, John Orville (1998).Namesakes 1900-1909: An Era Begins.Freshwater Press.ISBN978-0-912514-38-3.

- The Federal Reporter (Annotated), Volume 166: Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit Courts of Appeals and Circuit and District Courts of the United States. March-April, 1909.West Publishing Company,St. Paul, Minnesota