Sacred bull

This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Cattle are prominent in some religions and mythologies.As such, numerous peoples throughout the world have at one point in time honoredbullsas sacred. In theSumerian religion,Mardukis the "bull ofUtu".InHinduism,Shiva's steed isNandi,the Bull. Thesacred bullsurvives in the constellationTaurus.Thebull,whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural andreligiousincarnations as well as modern mentions inNew Agecultures.

In prehistoric art

[edit]

Aurochsare depicted in manyPaleolithicEuropean cave paintings such as those found atLascauxand Livernon in France. Their life force may have been thought to have magical qualities, for early carvings of the aurochs have also been found. The impressive and dangerous aurochs survived into theIron Agein Anatolia and the Near East and were worshipped throughout that area as sacred animals; the earliest remnants of bull worship can be found at neolithicÇatalhöyük.

In antiquity

[edit]Mesopotamia

[edit]

TheSumerianguardian deity calledlamassuwas depicted as hybrids with bodies of either winged bulls or lions and heads of human males. The motif of a winged animal with a human head is common to the Near East, first recorded inEblaaround 3000 BCE. The first distinct lamassu motif appeared inAssyriaduring the reign ofTiglath-Pileser IIas a symbol of power.

"The human-headed winged bulls protective genies called shedu or lamassu,... were placed as guardians at certain gates or doorways of the city and the palace. Symbols combining man, bull, and bird, they offered protection against enemies."[1]

The bull was also associated with the storm and rain god Adad,Hadador Iškur. The bull was his symbolic animal. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek godZeus;the Roman god Jupiter, asJupiter Dolichenus;the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-godTeshub;the Egyptian godAmun.WhenEnkidistributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as "great radiant bull, your name is heaven"and also called son ofAnu,lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.

TheSumerianEpic of Gilgameshdepicts the killing byGilgameshandEnkiduof theBull of Heavenas an act of defiance of the gods.

Egypt

[edit]

InAncient Egyptmultiple sacred bulls were worshiped. A long succession of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god's priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and buried. The mother-cows of these animals were also revered, and buried in separate locations.[2]

- In the Memphite region, theApiswas seen as the embodiment ofPtahand later ofOsiris.Some of the Apis bulls were buried in largesarcophagiin the underground vaults of theSerapeum of Saqqara,which was rediscovered byAuguste Mariettein 1851.[2]

- MnevisofHeliopoliswas the embodiment ofAtum-Ra.[2]

- BuchisofHermonthiswas linked with the godsRaandMontu.The catacombs for these bulls are now know as theBucheum.Multiple Buchis mummies were foundin situduring excavations in the 1930s. Some of their sarcophagi are similar to those in the Serapeum, others are polylithic (made from multiple stones).[2]

Ka,in Egyptian, is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull.[3]Andrew Gordon, an Egyptologist, and Calvin Schwabe, a veterinarian, argue that the origin of theankhis related to two other signs of uncertain origin that often appear alongside it: thewas-sceptre,representing "power" or "dominion", and thedjedpillar, representing "stability". According to this hypothesis, the form of each sign is drawn from a part of the anatomy of a bull, like some other hieroglyphic signs that are known to be based on body parts of animals. In Egyptian belief semen was connected with life and, to some extent, with "power" or "dominion", and some texts indicate the Egyptians believed semen originated in the bones. Therefore, Calvin and Schwabe suggest the signs are based on parts of the bull's anatomy through which semen was thought to pass: the ankh is athoracic vertebra,thedjedis thesacrumandlumbar vertebrae,and thewasis the dried penis of the bull.[4]

Central Anatolia

[edit]

We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary atÇatalhöyükin Central Anatolia. The sacred bull of theHattians,whose elaborate standards were found atAlaca Höyükalongside those of thesacred stag,survived inHurrianandHittite mythologyas Seri and Hurri ( "Day" and "Night" ), the bulls who carried the weather godTeshubon their backs or in his chariot and grazed on the ruins of cities.[5]

Crete

[edit]

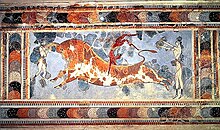

Bulls were a central theme in theMinoan civilization,with bull heads and bull horns used as symbols in theKnossospalace. Minoanfrescosandceramicsdepictbull-leaping,in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns.

Iran

[edit]

TheIranian languagetexts and traditions ofZoroastrianismhave several different mythological bovine creatures. One of these isGavaevodata,which is theAvestanname of ahermaphroditic"uniquely created (-aevo.data) cow (gav-) ", one ofAhura Mazda's six primordial material creations that becomes the mythological progenitor of all beneficent animal life. Another Zoroastrian mythological bovine is Hadhayans, a gigantic bull so large that it could straddle the mountains and seas that divide theseven regions of the earth,and on whose back men could travel from one region to another. In medieval times, Hadhayans also came to be known as Srīsōk (Avestan *Thrisaok,"three burning places" ), which derives from a legend in which three"Great Fires"were collected on the creature's back. Yet another mythological bovine is that of the unnamed creature in theCow's Lament,an allegorical hymn attributed toZoroasterhimself, in which the soul of a bovine (geush urvan) despairs over her lack of protection from an adequate herdsman. In the allegory, the cow represents humanity's lack of moral guidance, but in later Zoroastrianism, Geush Urvan became ayazatarepresentingcattle.The 14th day of the month is named after her and is under her protection.

South Asia and South East Asia

[edit]Vedic culture

[edit]

Bulls also appear on seals from theIndus Valley civilisation.

Nandiappears inHindu mythologyas the primary vehicle and the principalgana(follower) ofShiva.

In Rig Veda, Indra was often praised as a Bull (Vrsabha – 'vrsa' means he and bha means being or uksan- a bull aged five to nine years, which is still growing or just reached its full growth), with bull being an icon of power and virile strength not just in Aryan literature but in many IE[clarification needed]cultures.[6]

Vrsha means "to shower or to spray", in this context Indra showers strength and virility.

Meitei culture

[edit]

Kao (bull),a supernatural divine bull, appears in ancientMeitei mythologyandfolkloreofAncient Manipur(Kangleipak). In the legend of theKhamba Thoibiepic,Nongban Kongyamba,a nobleman of ancientMoirangrealm, pretended to be anoracleand falsely prophesied that the people of Moirang would lead to miserable lives, if the powerfulKao (bull)roaming freely in theKhumankingdom, wasn't offered to GodThangjing(Old Manipuri:Thangching), the presiding deity ofMoirang.OrphanKhumanprinceKhambawas chosen to capture the bull, as he was known for his valor and faithfulness. Since to capture the bull without killing it was not an easy task, Khamba's motherly sisterKhamnudisclosed to Khamba the secrets of the bull, with which the bull was able to get captured.[7][8][9]

Cyprus

[edit]InCyprus,bull masks made from real skulls were worn in rites. Bull-masked terracotta figurines[10]and Neolithic bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus.

Levant

[edit]

Bull figurines are common finds on archaeological sites across the Levant;[citation needed]two examples are the 16th century BCE (Middle Bronze Age) bull calf fromAshkelon,[11]and the 12th century BCE (Iron Age I) bull found at the so-calledBull SiteinSamariaon theWest Bank.[12] BothBaʿalandElwere associated with the bull inUgaritictexts, as it symbolized both strength and fertility.[13]

Exodus32:4[14]reads "He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, 'This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt'."

Nehemiah9:18[15]reads "even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, 'This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!' They committed terrible blasphemies."

Calf-idols are referred to later in theTanakh,such as in theBook of Hosea,[16]which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures.[citation needed]

Solomon's "Molten Sea"basin stood on twelve brazen bulls.[17][18]

Young bulls were set as frontier markers atDanandBethel,the frontiers of theKingdom of Israel.[citation needed]

Much later, inAbrahamic religions,the bull motif became a bulldemonor the "horned devil" in contrast and conflict to earlier traditions. The bull is familiar inJudeo-Christiancultures from theBiblicalepisode wherein anidolof thegolden calf(Hebrew:עֵגֶּל הַזָהָב) is made byAaronand worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of the Sinai Peninsula (Book of Exodus). The text of theHebrew Biblecan be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representingYahwehhimself, perhaps through an association orreligious syncretismwith Egyptian orLevantinebull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.[citation needed]

Greece

[edit]

Among theTwelve Olympians,Hera'sepithetBo-opisis usually translated "ox-eyed" Hera, but the term could just as well apply if the goddess had the head of a cow, and thus the epithet reveals the presence of an earlier, though not necessarily more primitive, iconic view. (Heinrich Schlieman,1976) Classical Greeks never otherwise referred to Hera simply as the cow, though her priestessIowas so literally a heifer that she was stung by a gadfly, and it was in the form of a heifer thatZeuscoupled with her. Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born PhoenicianEuropaand brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Dionysuswas another god of resurrection who was strongly linked to the bull. In a worship hymn fromOlympia,at a festival for Hera,Dionysusis also invited to come as a bull, "with bull-foot raging." "Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and inKyzikoshe has a tauromorphic image, "Walter Burkertrelates, and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by theTitans.[19]

For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to theCretan Bull:Theseusof Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull ofMarathon(the "Marathonian bull" ) before he faced theMinotaur(Greek for "Bull of Minos" ), who the Greeks imagined as a man with the head of a bull at the center of thelabyrinth.Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family's shame. Living in solitude made the boy wild and ferocious, unable to be tamed or beaten. YetWalter Burkert's constant warning is, "It is hazardous to project Greek tradition directly into theBronze Age."[20]Only one Minoan image of a bull-headed man has been found, a tinyMinoan sealstonecurrently held in the Archaeological Museum ofChania.

In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as theiragalma,a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.

Roman Empire

[edit]

The religious practices of theRoman Empireof the 2nd to 4th centuries included thetaurobolium,in which a bull was sacrificed for the well-being of the people and the state. Around the mid-2nd century, the practice became identified with the worship ofMagna Mater,but was not previously associated only with that cult (cultus). Public taurobolia, enlisting the benevolence of Magna Mater on behalf of the emperor, became common in Italy and Gaul, Hispania and Africa. The last public taurobolium for which there is an inscription was carried out atMactar in Numidiaat the close of the 3rd century. It was performed in honor of the emperorsDiocletianandMaximian.

Another Romanmystery cultin which a sacrificial bull played a role was that of the 1st–4th centuryMithraic Mysteries.In the so-called "tauroctony"artwork of that cult (cultus), and which appears in all its temples, the godMithrasis seen to slay a sacrificial bull. Although there has been a great deal of speculation on the subject, the myth (i.e. the "mystery", the understanding of which was the basis of the cult) that the scene was intended to represent remains unknown. Because the scene is accompanied by a great number of astrological allusions, the bull is generally assumed to represent the constellation ofTaurus.The basic elements of the tauroctony scene were originally associated withNike,the Greek goddess of victory.

Macrobiuslists the bull as an animal sacred to the godNeto/Neito,possibly being sacrifices to the deity.[21]

Celts

[edit]Tarvos Trigaranus(the "bull with three cranes" ) is pictured on ancientGaulishreliefs alongside images of gods, such as in the cathedrals atTrierand atNotre Dame de Paris.InIrish mythology,theDonn Cuailngeand theFinnbhennachare prized bulls that play a central role in the epicTáin Bó Cúailnge( "TheCattle Raidof Cooley "). Early medieval Irish texts also mention thetarbfeis(bull feast), a shamanistic ritual in which a bull would be sacrificed and a seer would sleep in the bull's hide to have a vision of the future king.[22]

Pliny the Elder,writing in the first century AD, describes a religious ceremony inGaulin which white-claddruidsclimbed a sacredoak,cut down themistletoegrowing on it, sacrificed two white bulls and used the mistletoe to cure infertility:[23]

The druids—that is what they call their magicians—hold nothing more sacred than the mistletoe and a tree on which it is growing, provided it isValonia oak.…Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on thesixth day of the moon….Hailing themoonin a native word that means 'healing all things,' they prepare a ritualsacrificeandbanquetbeneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whosehornsare bound for the first time on this occasion. Apriestarrayed in whitevestmentsclimbs the tree and, with a goldensickle,cuts down the mistletoe, which is caught in a whitecloak.Then finally they kill the victims, praying to agodto render his gift propitious to those on whom he has bestowed it. They believe that mistletoe given in drink will impart fertility to any animal that is barren and that it is anantidoteto all poisons.[24]

Bull sacrifices at the time of theLughnasafestival were recorded as late as the 18th century atCois Fharraigein Ireland (where they were offered toCrom Dubh) and atLoch Mareein Scotland (where they were offered to SaintMáel Ruba).[25]

Medieval and modern and other uses

[edit]The practice ofbullfightingin theIberian Peninsulaandsouthern Franceare connected with the legends ofSaturninofToulouseand his protégé inPamplona,Fermin.These are inseparably linked to bull-sacrifices by the vivid manner of their martyrdoms set by Christianhagiographyin the third century.

In some Christian traditions,Nativity scenesare carved or assembled atChristmastime. Many show a bull or anoxnear the babyJesus,lying in a manger. Traditional songs of Christmas often tell of the bull and the donkey warming the infant with their breath. This refers (or, at least, is referred) to the beginning of the book of the prophet Isaiah, where he says: "The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib." (Isaiah 1:3)

Oxen are some of theanimals sacrificedbyGreek Orthodoxbelievers in some villages of Greece. It is specially associated to the feast of SaintCharalambos. This practice ofkourbaniahas been repeatedly criticized by church authorities.

The ox is the symbol ofLuke the Evangelist.[citation needed]

Among theVisigoths,the oxenpulling the wagon with the corpseofSaint Emilianlead to the correct burial site (San Millán de la Cogolla, La Rioja).

Taurus(Latinfor "the Bull" ) is one of theconstellationsof thezodiac,which means it is crossed by the plane of theecliptic.Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in thenorthern hemisphere's winter sky. It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to at least theEarly Bronze Agewhen it marked the location of the Sun during the springequinox.Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of AncientSumer,Akkad,Assyria,Babylon,Egypt,Greece,andRome.

In his book 'Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wildwood' (2016),John Matthewsinterprets the scene from the ballad in which Sir Richard-at-Lee awards, for the love ofRobin Hood,a prize of a white bull to the winner of a wrestling match as seeming 'to hark back to an ancient time when the presentation of such a valuable, and probably sacred beast, would have represented an offering to the gods'. For Matthews, the Bull-running at Tutbury, mentioned in another Robin Hood ballad, may have had similar significance.[26]

See also

[edit]- Bucranium

- Bugonia

- Camahueto

- Cattle in religion

- Deer in mythology

- Golden calf

- Horned deity

- Mithraism

- Red heifer

- Taurobolium

References

[edit]- ^Castor Marie-José, Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia,Musée du Louvre

- ^abcdDodson, Aidan (2005)."Bull Cults".Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt.pp. 72–102.doi:10.5743/cairo/9789774248580.003.0004.ISBN9789774248580.

- ^Gordon & Schwabe (2004).The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt.Brill / Styx. pp. 104, 127–129.ISBN978-90-04-12391-5.

- ^Gordon, Andrew H.; Schwabe, Calvin (2004).The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt.Brill / Styx. pp. 104, 127–129.ISBN978-90-04-12391-5.

- ^Hawkes and Woolley, 1963; Vieyra, 1955

- ^Pronk, Tijmen (January 1, 2009)."Sanskrit (v)rsabhá-, Greek αρσην, ερσην: the spraying bull of Indo-European?".Historische Sprachforschung– via academia.edu.

- ^Indian Antiquary.Popular Prakashan. 1877. p. 222.

- ^""Kao - the sacred bull" by Laihui ".e-pao.net.

- ^"KAO - A Glimpse of Manipuri Opera".e-pao.net.

- ^Burkert 1985

- ^"A Calf and Its Shrine".Ashkelon: A Retrospecitve - 30 Years of the Leon Levy Expedition (Rockefeller Archaeological Museum).TheIsrael Museum,Jerusalem. 2016.Retrieved5 February2021.

- ^Mazar, Amihai(1999). "The 'Bull Site' and the 'Einun Pottery' Reconsidered".Palestine Exploration Quarterly.131(2): 1944-148.doi:10.1179/peq.1999.131.2.144.

- ^Miller, Patrick (2000),Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays,Continuum Int'l Publishing Group, p. 32,ISBN1-84127-142-X.

- ^biblelexicon.org,Exodus 32:4

- ^biblelexicon.org,Nehemiah 9:18

- ^"Hosea 10:5 The people who live in Samaria fear for the calf-idol of Beth Aven. Its people will mourn over it, and so will its idolatrous priests, those who had rejoiced over its splendor, because it is taken from them into exile".Bible.cc.Retrieved2012-10-30.

- ^"1 Kings 7:25 The Sea stood on twelve bulls, three facing north, three facing west, three facing south and three facing east. The Sea rested on top of them, and their hindquarters were toward the center".Bible.cc.Retrieved2012-10-30.

- ^"Jeremiah 52:20 The bronze from the two pillars, the Sea and the twelve bronze bulls under it, and the movable stands, which King Solomon had made for the temple of the LORD, was more than could be weighed".Bible.cc.Retrieved2012-10-30.

- ^Burkert 1985 pp. 64, 132

- ^Burkert 1985 p. 24

- ^Macrobius,Saturnalia,Book I, XIX

- ^Davidson, Hilda Ellis(1988).Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions.Syracuse University Press. p. 51.

- ^Miranda J. Green. (2005)Exploring the World of the Druids.London: Thames & Hudson.ISBN0-500-28571-3.Page 18–19

- ^Natural History,XVI, 95

- ^MacNeill, Máire.The Festival of Lughnasa: A Study of the Survival of the Celtic Festival of the Beginning of Harvest.Oxford University Press, 1962. pp.407, 410

- ^Matthews, John (2019).Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wild Wood.Stroud: Amberly Publishing. pp. 23, 45.ISBN9781445690773.

Sources

[edit]- Burkert, Walter,Greek Religion,1985

- Campbell, JosephOccidental Mythology"2.The Consort of the Bull", 1964.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta;Woolley, Leonard:Prehistory and the Beginnings of Civilization,v. 1 (NY, Harper & Row, 1963)

- Vieyra, Maurice:Hittite Art, 2300-750 B.C.(London, A. Tiranti, 1955)

- Jeremy B. Rutter,The Three Phases of the Taurobolium,Phoenix (1968).

- Heinrich Schliemann,Troy and its Remains(NY, Arno Press, 1976) pp. 113–114.

External links

[edit]- An exhibit on the tombs of Alaca Höyükat theMetropolitan Museum of Artincludes one example of the bull standards.

- Bull Tattoo ArtThe image of the bull in tattoo art.