Shaivism

Shiva(above) is the primary God in Shaivism. |

| Part ofa serieson |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part ofa serieson |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Shaivism(/ˈʃaɪvɪzəm/;Sanskrit:शैवसम्प्रदायः,romanized:Śaivasampradāyaḥa) is one of the majorHindu traditions,which worshipsShiva[1][2][3]as theSupreme Being.One of the largest Hindu denominations,[4][5]it incorporates many sub-traditions ranging from devotionaldualistic theismsuch asShaiva Siddhantatoyoga-orientatedmonisticnon-theism such asKashmiri Shaivism.[6][7][8]It considers both theVedasand theAgamatexts as important sources of theology.[9][10][11]According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, Shaivism is thesecond-largest Hindu sect,constituting about 252 million or 26.6% of Hindus.[4][12]

Shaivism developed as an amalgam of pre-Vedic religions and traditions derived from the southernTamilShaiva Siddhantatraditions and philosophies, which were assimilated in the non-Vedic Shiva-tradition.[13]In the process ofSanskritisationand theformation of Hinduism,starting in the last centuriesBCE,these pre-Vedic traditions became aligned with the Vedic deityRudraand other Vedic deities, incorporating the non-Vedic Shiva-traditions into theVedic-Brahmanical fold.[2][14]

Both devotional and monistic Shaivism became popular in the 1st millennium CE, rapidly becoming the dominant religious tradition of many Hindu kingdoms.[2]It arrived inSoutheastAsia shortly thereafter, leading to the construction of thousands of Shaiva temples on the islands of Indonesia as well as Cambodia and Vietnam, co-evolving withBuddhismin these regions.[15][16]

Shaivite theology ranges from Shiva being the creator, preserver, and destroyer to being the same as theAtman(Self) within oneself and every living being. It is closely related toShaktism,and some Shaivas worship in both Shiva and Shakti temples.[8]It is the Hindu tradition that most accepts ascetic life and emphasizes yoga, and like other Hindu traditions encourages an individual to discover and be one with Shiva within.[6][7][17]The followers of Shaivism are called Shaivas or Shaivites.

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]Shiva (śiva,Sanskrit:शिव) literally means kind, friendly, gracious, or auspicious.[18][19]As a proper name, it means "The Auspicious One".[19]

The word Shiva is used as an adjective in theRig Veda,as an epithet for severalRigvedic deities,includingRudra.[20]The term Shiva also connotes "liberation, final emancipation" and "the auspicious one", this adjective sense of usage is addressed to many deities in Vedic layers of literature.[21][22]The term evolved from the VedicRudra-Shivato the nounShivain the Epics and the Puranas, as an auspicious deity who is the "creator, reproducer and dissolver".[21][23]

The Sanskrit wordśaivaorshaivameans "relating to the god Shiva",[24]while the related beliefs, practices, history, literature and sub-traditions constitute Shaivism.[25]

Overview

[edit]The reverence for Shiva is one of the pan-Hindu traditions found widely across South Asia predominantly in Southern India, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.[26][27]While Shiva is revered broadly, Hinduism itself is a complex religion and a way of life, with a diversity of ideas onspiritualityand traditions. It has no ecclesiastical order, no unquestionable religious authorities, no governing body, no prophet(s) nor any binding holy book; Hindus can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic, or humanist.[28][29][30]

Shaivism is a major tradition within Hinduism with a theology that is predominantly related to the Hindu god Shiva. Shaivism has many different sub-traditions with regional variations and differences in philosophy.[31]Shaivism has a vast literature with different philosophical schools ranging fromnondualism,dualism,andmixed schools.[32]

Origins and history

[edit]

The origins of Shaivism are unclear and a matter of debate among scholars, as it is an amalgam of pre-Vedic cults and traditions and Vedic culture.[34]

Indus Valley Civilisation

[edit]

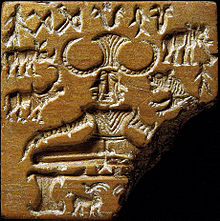

Some trace the origins to theIndus Valley civilization,which reached its peak around 2500–2000 BCE.[35][36]Archeological discoveries show seals that suggest a deity that somewhat appears like Shiva. Of these is thePashupati seal,which early scholars interpreted as someone seated in a meditating yoga pose surrounded by animals, and with horns.[37]This "Pashupati" (Lord of Animals,Sanskritpaśupati)[38]seal has been interpreted by these scholars as a prototype of Shiva.Gavin Floodcharacterizes these views as "speculative", saying that it is not clear from the seal if the figure has three faces, or is seated in a yoga posture, or even that the shape is intended to represent a human figure.[36][39]

Other scholars state that the Indus Valley script remains undeciphered, and the interpretation of the Pashupati seal is uncertain. According to Srinivasan, the proposal that it is proto-Shiva may be a case of projecting "later practices into archeological findings".[40][41]Similarly, Asko Parpola states that other archaeological finds such as the early Elamite seals dated to 3000–2750 BCE show similar figures and these have been interpreted as "seated bull" and not a yogi, and the bull interpretation is likely more accurate.[36][42]

Vedic elements

[edit]TheRigveda(~1500–1200 BCE) has the earliest clear mention ofRudra( "Roarer" ) in its hymns 2.33, 1.43 and 1.114. The text also includes aSatarudriya,an influential hymn with embedded hundred epithets for Rudra, that is cited in many medieval era Shaiva texts as well as recited in major Shiva temples ofHindusin contemporary times. Yet, the Vedic literature only present scriptural theology, but does not attest to the existence of Shaivism.[36]

Emergence of Shaivism

[edit]

According toGavin Flood,"the formation of Śaiva traditions as we understand them begins to occur during the period from 200 BC to 100 AD."[46]Shiva was originally probably not a Brahmanical god,[47][48]but eventually came to be incorporated into the Brahmanical fold.[48][49]The pre-Vedic Shiva acquired a growing prominence as its cult assimilated numerous "ruder faiths" and their mythologies,[50]and the Epics and Puranas preserve pre-Vedic myths and legends of these traditions assimilated by the Shiva-cult.[49]Shiva's growing prominence was facilitated by identification with a number of Vedic deities, such asPurusha,Rudra,Agni,Indra,Prajāpati,Vāyu,among others.[51]The followers of Shiva were gradually accepted into the Brahmanical fold, becoming allowed to recite some of the Vedic hymns.[52]

Patanjali'sMahābhāṣya,dated to the 2nd century BCE, mentions the termShiva-bhagavatain section 5.2.76. Patanjali, while explaining Panini's rules of grammar, states that this term refers to a devotee clad in animal skins and carrying anayah sulikah(iron spear, trident lance)[53]as an icon representing his god.[46][54][55]

TheShvetashvatara Upanishadmentions terms such as Rudra, Shiva, and Maheshwaram,[56][57][36][58]but its interpretation as a theistic or monistic text of Shaivism is disputed.[59][60]The dating of theShvetashvatarais also in dispute, but it is likely a lateUpanishad.[61]

TheMahabharatamentions Shaiva ascetics, such as in chapters 4.13 and 13.140.[62]Other evidence that is possibly linked to the importance of Shaivism in ancient times are in epigraphy and numismatics, such as in the form of prominent Shiva-like reliefs onKushan Empireera gold coins. However, this is controversial, as an alternate hypothesis for these reliefs is based onZoroastrianOesho.According to Flood, coins dated to the ancient Greek, Saka and Parthian kings who ruled parts of the Indian subcontinent after the arrival ofAlexander the Greatalso show Shiva iconography; however, this evidence is weak and subject to competing inferences.[46][63]

In the early centuries of the common era is the first clear evidence ofPāśupata Shaivism.[2]The inscriptions found in the Himalayan region, such as those in the Kathmandu valley ofNepalsuggest that Shaivism (particularly Pāśupata) was established in this region by the 5th century, during the lateGuptasera. These inscriptions have been dated by modern techniques to between 466 and 645 CE.[64]

Puranic Shaivism

[edit]

During theGupta Empire(c. 320–500 CE) the genre ofPurāṇaliterature developed in India, and many of these Puranas contain extensive chapters on Shaivism – along withVaishnavism,Shaktism,Smarta Traditionsof Brahmins and other topics – suggesting the importance of Shaivism by then.[36][54]

The most important Shaiva Purāṇas of this period include theShiva Purāṇa,theSkanda Purāṇa,and theLinga Purāṇa.[36][63][65]

Post-Gupta development

[edit]

Most of the Gupta kings, beginning withChandragupta II(Vikramaditya) (375–413 CE) were known as Parama Bhagavatas orBhagavataVaishnavasand had been ardent promoters ofVaishnavism.[66][67]But following theHunainvasions, especially those of theAlchon Hunscirca 500 CE, theGupta Empiredeclined and fragmented, ultimately collapsing completely, with the effect of discrediting Vaishnavism, the religion it had been so ardently promoting.[68]The newly arising regional powers in central and northern India, such as theAulikaras,theMaukharis,theMaitrakas,theKalacurisor theVardhanaspreferred adopting Shaivism instead, giving a strong impetus to the development of the worship ofShiva.[68]Vaishnavism remained strong mainly in the territories which had not been affected by these events:South IndiaandKashmir.[68]

In the early 7th century, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrimXuanzang(Huen Tsang) visited India and wrote a memoir in Chinese that mentions the prevalence of Shiva temples all over NorthIndian subcontinent,including in theHindu Kushregion such asNuristan.[69][70]Between the 5th and 11th century CE, major Shaiva temples had been built in central, southern and eastern regions of the subcontinent, including those atBadami cave temples,Aihole,Elephanta Caves,Ellora Caves(Kailasha, cave 16),Khajuraho,Bhuvaneshwara, Chidambaram, Madurai, and Conjeevaram.[69]

Major scholars of competing Hindu traditions from the second half of the 1st millennium CE, such asAdi Shankaraof Advaita Vedanta andRamanujaof Vaishnavism, mention several Shaiva sects, particularly the four groups: Pashupata, Lakulisha, tantric Shaiva and Kapalika. The description is conflicting, with some texts stating the tantric, puranik and Vedic traditions of Shaivism to be hostile to each other while others suggest them to be amicable sub-traditions. Some texts state that Kapalikas reject the Vedas and are involved in extreme experimentation,[note 2]while others state the Shaiva sub-traditions revere the Vedas but are non-Puranik.[73]

South India

[edit]Shaivism was the predominant tradition in South India, co-existing with Buddhism and Jainism, before the VaishnavaAlvarslaunched theBhakti movementin the 7th century, and influential Vedanta scholars such asRamanujadeveloped a philosophical and organizational framework that helped Vaishnavism expand. Though both traditions of Hinduism have ancient roots, given their mention in the epics such as theMahabharata,Shaivism flourished in South India much earlier.[74]

The Mantramarga of Shaivism, according to Alexis Sanderson, provided a template for the later though independent and highly influential Pancaratrika treatises of Vaishnavism. This is evidenced in Hindu texts such as theIsvarasamhita,Padmasamhita,andParamesvarasamhita.[74]

Along with the Himalayan region stretching from Kashmir through Nepal, the Shaiva tradition in South India has been one of the largest sources of preserved Shaivism-related manuscripts from ancient and medieval India.[76]The region was also the source of Hindu arts, temple architecture, and merchants who helped spread Shaivism into southeast Asia in early 1st millennium CE.[77][78][79]

There are tens of thousands of Hindu temples where Shiva is either the primary deity or reverentially included in anthropomorphic or aniconic form (lingam, orsvayambhu).[80][81]Numerous historic Shaiva temples have survived in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, parts of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.[82]Gudimallamis the oldest known lingam and has been dated to between 3rd to 1st-century BCE. It is a carved five feet high stone lingam with an anthropomorphic image of Shiva on one side. This ancient lingam is inChittoordistrict of Andhra Pradesh.[81][83][84]

Southeast Asia

[edit]

Shaivism arrived in a major way in southeast Asia from south India, and to much lesser extent into China and Tibet from the Himalayan region. It co-developed with Buddhism in this region, in many cases.[85]For example, in theCaves of the Thousand Buddhas,a few caves include Shaivism ideas.[86][note 3]The epigraphical and cave arts evidence suggest that Shaiva Mahesvara and Mahayana Buddhism had arrived in Indo-China region in theFunanperiod, that is in the first half of the 1st millennium CE.[78][79]In Indonesia, temples at archaeological sites and numerous inscription evidence dated to the early period (400 to 700 CE), suggest that Shiva was the highest god. This co-existence of Shaivism and Buddhism in Java continued through about 1500 CE when both Hinduism and Buddhism were replaced with Islam,[88]and persists today in the province of Bali.[89]

The Shaivist and Buddhist traditions overlapped significantly in southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, Cambodia, and Vietnam between the 5th and the 15th century. Shaivism and Shiva held the paramount position in ancient Java, Sumatra, Bali, and neighboring islands, though the sub-tradition that developed creatively integrated more ancient beliefs that pre-existed.[90]In the centuries that followed, the merchants and monks who arrived in Southeast Asia, brought Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Buddhism, and these developed into a syncretic, mutually supporting form of traditions.[90][91]

Indonesia

[edit]InBalinese Hinduism,Dutch ethnographers further subdividedSiwa (shaivaites)Sampradaya"into five – Kemenuh, Keniten, Mas, Manuba and Petapan. This classification was to accommodate the observed marriage between higher caste Brahmana men with lower caste women.[92]

Beliefs and practices

[edit]Shaivism centers around Shiva, but it has many sub-traditions whose theological beliefs and practices vary significantly. They range from dualistic devotional theism to monistic meditative discovery of Shiva within oneself. Within each of these theologies, there are two sub-groups. One sub-group is called Vedic-Puranic, who use the terms such as "Shiva, Mahadeva, Maheshvara and others" synonymously, and they use iconography such as theLinga,Nandi,Trishula(trident), as well as anthropomorphic statues of Shiva in temples to help focus their practices.[93]Another sub-group is called esoteric, which fuses it with abstractSivata(feminine energy) orSivatva(neuter abstraction), wherein the theology integrates the goddess (Shakti) and the god (Shiva) with Tantra practices and Agama teachings. There is a considerable overlap between these Shaivas and the Shakta Hindus.[93]

Vedic, Puranik, and esoteric Shaivism

[edit]Scholars such as Alexis Sanderson discuss Shaivism in three categories: Vedic, Puranik and non-Puranik (esoteric, tantric).[94][95]They place Vedic and Puranik together given the significant overlap, while placing Non-Puranik esoteric sub-traditions as a separate category.[95]

- Vedic-Puranik.The majority within Shaivism follow the Vedic-Puranik traditions. They revere the Vedas and the Puranas and hold beliefs that span from dualistic theism, such as ShivaBhakti(devotionalism), to monistic non-theism dedicated to yoga and a meditative lifestyle. This sometimes involves renouncing household life for monastic pursuits of spirituality.[96]The Yoga practice is particularly pronounced in nondualistic Shaivism, with the practice refined into a methodology such as four-foldupaya:being pathless (anupaya, iccha-less, desire-less), being divine (sambhavopaya,jnana,knowledge-full), being energy (saktopaya,kriya,action-full) and being individual (anavopaya).[97][note 4]

- Non-Puranik.These are esoteric, minority sub-traditions wherein devotees are initiated (dīkṣa) into a specific cult they prefer. Their goals vary, ranging from liberation in current life (mukti) to seeking pleasures in higher worlds (bhukti). Their means also vary, ranging from meditativeatimargaor "outer higher path" versus those whose means are recitation-drivenmantras.Theatimargasub-traditions include Pashupatas and Lakula. According to Sanderson, the Pashupatas[note 5]have the oldest heritage, likely from the 2nd century CE, as evidenced by ancient Hindu texts such as theShanti Parvabook of theMahabharataepic.[94][95]The tantric sub-tradition in this category is traceable to post-8th to post-11th century depending on the region of Indian subcontinent, paralleling the development of Buddhist and Jain tantra traditions in this period.[98]Among these are the dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta and Bhairava Shaivas (non-Saiddhantika), based on whether they recognize any value in Vedic orthopraxy.[99]These sub-traditions cherish secrecy, special symbolic formulae, initiation by a teacher and the pursuit ofsiddhi(special powers). Some of these traditions also incorporate theistic ideas, elaborate geometric yantra with embedded spiritual meaning, mantras and rituals.[98][100][101]

Shaivism versus other Hindu traditions

[edit]Shaivism sub-traditions subscribe to various philosophies, are similar in some aspects and differ in others. These traditions compare with Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism as follows:

| Shaiva Traditions | Vaishnava Traditions | Shakta Traditions | Smarta Traditions | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scriptural authority | Vedas, Upanishads and Agamas | Vedas, Upanishads and Agamas | Vedas and Upanishads | Vedas and Upanishads | [5][102] |

| Supreme deity | Shiva | Vishnu | Devi | None (ConsidersParabrahmanto be so) | [103][104] |

| Creator | Shiva | Vishnu | Devi | Brahman principle | [103][105] |

| Avatar | Minor | Key concept | Significant | Minor | [5][106][107] |

| Monasticlife | Recommends | Accepts | Accepts | Recommends | [5][108][109] |

| Rituals,Bhakti | Affirms[110][111][112] | Affirms | Affirms | Optional[113] | [114] |

| AhimsaandVegetarianism | Recommends,[110]Optional | Affirms | Optional | Recommends, Optional | [115][116] |

| Free will,Maya,Karma | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | [103] |

| Metaphysics | Brahman(Shiva),Atman(Self) | Brahman (Vishnu), Atman | Brahman (Devi), Atman | Brahman, Atman | [103] |

| Epistemology (Pramana) |

1. Perception 2. Inference 3. Reliable testimony 4. Self-evident[117] |

1. Perception 2. Inference 3. Reliable testimony |

1. Perception 2. Inference 3. Reliable testimony |

1. Perception 2. Inference 3. Comparison and analogy 4. Postulation, derivation 5. Negative/cognitive proof 6. Reliable testimony |

[118][119][120] |

| Philosophy | Dvaita, qualified advaita, advaita | Vishishtadvaita, Dvaita, qualified advaita, advaita | Shakti-advaita | Advaita, qualified advaita | [121][122] |

| Liberation (Soteriology) |

Jivanmukta, Charya-Kriyā-Yoga-Jnana[123] |

Videhamukti, Yoga, champions householder life |

Bhakti, Tantra, Yoga | Jivanmukta, Advaita, Yoga, champions monastic life |

[124][125] |

Texts

[edit]Shaiva manuscripts that have survived

(post-8th century)Nepal and Himalayan region = 140,000

South India = 8,600

Others (Devanagiri) = 2,000

Bali and SE Asia = Many

Over its history, Shaivism has been nurtured by numerous texts ranging from scriptures to theological treatises. These include the Vedas and Upanishads, the Agamas, and theBhasya.According to Gavin Flood – a professor at Oxford University specializing in Shaivism and phenomenology, Shaiva scholars developed a sophisticated theology, in its diverse traditions.[127]Among the notable and influential commentaries bydvaita(dualistic) theistic Shaivism scholars were the 8th century Sadyajoti, the 10th century Ramakantha, 11th century Bhojadeva.[127]The dualistic theology was challenged by the numerous scholars ofadvaita(nondualistic, monistic) Shaivism persuasion such as the 8th/9th century Vasugupta,[note 6]the 10th century Abhinavagupta and 11th century Kshemaraja, particularly the scholars of the Pratyabhijna, Spanda and Kashmiri Shaivism schools of theologians.[127][129][130]

Vedas and Principal Upanishads

[edit]The Vedas and Upanishads are shared scriptures ofHinduism,while the Agamas are sacred texts of specific sub-traditions.[10]The surviving Vedic literature can be traced to the 1st millennium BCE and earlier, while the surviving Agamas can be traced to 1st millennium of the common era.[10]The Vedic literature, in Shaivism, is primary and general, while Agamas are special treatise. In terms of philosophy and spiritual precepts, no Agama that goes against the Vedic literature, states Mariasusai Dhavamony, will be acceptable to the Shaivas.[10]According to David Smith, "a key feature of the Tamil Saiva Siddhanta, one might almost say its defining feature, is the claim that its source lies in the Vedas as well as the Agamas, in what it calls the Vedagamas".[9]This school's view can be summed as,

The Veda is the cow, the true Agama its milk.

— Umapati, Translated by David Smith[9]

TheŚvetāśvataraUpanishad(400–200 BCE)[131]is the earliest textual exposition of a systematic philosophy of Shaivism.[note 7]

Shaiva minor Upanishads

[edit]Shaivism-inspired scholars authored 14 Shiva-focussed Upanishads that are called the Shaiva Upanishads.[132]These are considered part of 95 minor Upanishads in theMuktikāUpanishadic corpus of Hindu literature.[132][133]The earliest among these were likely composed in 1st millennium BCE, while the last ones in the late medieval era.[134]

The Shaiva Upanishads present diverse ideas, ranging frombhakti-style theistic dualism themes to a synthesis of Shaiva ideas with Advaitic (nondualism), Yoga, Vaishnava and Shakti themes.[135]

| Shaiva Upanishad | Composition date | Topics | Reference |

| Kaivalya Upanishad | 1st millennium BCE | Shiva, Atman, Brahman,Sannyasa,Self-knowledge | [136][137][138] |

| Atharvashiras Upanishad | 1st millennium BCE | Rudra, Atman, Brahman, Om, monism | [139][140][141] |

| Atharvashikha Upanishad | 1st millennium BCE | Shiva, Om, Brahman, chanting, meditation | [142] |

| Brihajjabala Upanishad | Late medieval, post-12th century | Shiva, sacred ash, prayer beads,Tripundratilaka | [143] |

| Kalagni Rudra Upanishad | Unknown | Meaning of Tripundra (three lines tilaka), Ritual Shaivism | [144][145] |

| Dakshinamurti Upanishad | Unknown | Dakshinamurti as an aspect of Shiva, Atman, monism | [146] |

| Sharabha Upanishad | Unknown | Shiva as Sharabha | [147] |

| Akshamalika Upanishad | Late medieval, post-12th century CE | Rosary, japa, mantras, Om, Shiva, symbolism in Shaivism iconography | [148] |

| Rudrahridaya Upanishad | Unknown | Rudra-Uma, Male-Female are inseparable, nondualism | [149] |

| Bhasmajabala Upanishad | Late medieval, post-12th century | Shiva, sacred ash, body art, iconography, why rituals andVaranasiare important | [150][151] |

| Rudrakshajabala Upanishad | After the 10th century | Shiva, Bhairava, Rudraksha beads and mantra recitation | [132] |

| Ganapati Upanishad | 16th or 17th century | Ganesha, Shiva, Brahman, Atman, Om, Satcitananda | [152] |

| Pancabrahma Upanishad | About 7th century CE | Shiva, Sadashiva, nondualism,So'ham,Atman, Brahman, self-knowledge | [153][154] |

| Jabali Upanishad | unknown | Shiva, Pashupata theology, significance of ash and body art | [155] |

Shaiva Agamas

[edit]The Agama texts of Shaivism are another important foundation of Shaivism theology.[156]These texts include Shaivacosmology,epistemology, philosophical doctrines, precepts on meditation and practices, four kinds of yoga, mantras, meanings and manuals for Shaiva temples, and other elements of practice.[157][158]These canonical texts exist inSanskrit[157]and in south Indian languages such asTamil.[159]

The Agamas present a diverse range of philosophies, ranging fromtheistic dualismto absolutemonism.[160][161]In Shaivism, there are ten dualistic (dvaita) Agama texts, eighteen qualified monism-cum-dualism (bhedabheda) Agama texts and sixty four monism (advaita) Agama texts.[11]The Bhairava Shastras are monistic, while Shiva Shastras are dualistic.[110][162]

The Agama texts of Shaiva and Vaishnava schools are premised on existence ofAtman(Self) and the existence of an Ultimate Reality (Brahman) which is considered identical to Shiva in Shaivism.[7]The texts differ in the relation between the two. Some assert the dualistic philosophy of the individual Self and Ultimate Reality being different, while others state a Oneness between the two.[7]Kashmir Shaiva Agamas posit absolute oneness, that is God (Shiva) is within man, God is within every being, God is present everywhere in the world including all non-living beings, and there is no spiritual difference between life, matter, man and God.[7]While Agamas present diverse theology, in terms of philosophy and spiritual precepts, no Agama that goes against the Vedic literature, states Dhavamony, has been acceptable to the Shaivas.[10]

Traditions

[edit]

Shaivism is ancient, and over time it developed many sub-traditions. These broadly existed and are studied in three groups: theistic dualism, nontheistic monism, and those that combine features or practices of the two.[163][164]Sanderson presents the historic classification found in Indian texts,[165]namelyAtimargaof the Shaiva monks andMantramargathat was followed by both the renunciates (sannyasi) and householders (grihastha) in Shaivism.[166]Sub-traditions of Shaivas did not exclusively focus on Shiva, but others such as theDevi(goddess)Shaktism.[167]

Sannyasi Shaiva: Atimarga

[edit]The Atimarga branch of Shaivism emphasizes liberation (salvation) – or the end of allDukkha– as the primary goal of spiritual pursuits.[168]It was the path for Shaivaascetics,in contrast to Shaiva householders whose path was described as Mantramarga and who sought both salvation as well as the yogi-siddhi powers and pleasures in life.[169]The Atimarga revered theVedicsources of Shaivism, and sometimes referred to in ancient Indian texts as Raudra (from VedicRudra).[170]

Pashupata Atimargi

[edit]

Pashupata:(IAST:Pāśupatas) are the Shaivite sub-tradition with the oldest heritage, as evidenced by Indian texts dated to around the start of the common era.[94][95]It is a monist tradition, that considers Shiva to be within oneself, in every being and everything observed. The Pashupata path to liberation is one ofasceticismthat is traditionally restricted to Brahmin males.[172]Pashupata theology, according toShiva Sutras,aims for a spiritual state of consciousness where the Pashupata yogi "abides in one's own unfettered nature", where the external rituals feel unnecessary, where every moment and every action becomes an internal vow, a spiritual ritual unto itself.[173]

The Pashupatas derive their Sanskrit name from two words: Pashu (beast) and Pati (lord), where the chaotic and ignorant state, one imprisoned by bondage and assumptions, is conceptualized as the beast,[174]and the Atman (Self, Shiva) that is present eternally everywhere as the Pati.[175]The tradition aims at realizing the state of being one with Shiva within and everywhere. It has extensive literature,[175][176]and a fivefold path of spiritual practice that starts with external practices, evolving into internal practices and ultimately meditative yoga, with the aim of overcoming all suffering (Dukkha) and reaching the state of bliss (Ananda).[177][178]

The tradition is attributed to a sage from Gujarat namedLakulisha(~2nd century CE).[179]He is the purported author of thePashupata-sutra,a foundational text of this tradition. Other texts include thebhasya(commentary) onPashupata-sutraby Kaudinya, theGaṇakārikā,Pañchārtha bhāshyadipikāandRāśikara-bhāshya.[168]The Pashupatha monastic path was available to anyone of any age, but it required renunciation from fourAshrama (stage)into the fifth stage ofSiddha-Ashrama.The path started as a life near a Shiva temple and silent meditation, then a stage when the ascetic left the temple and did karma exchange (be cursed by others, but never curse back). He then moved to the third stage of life where he lived like a loner in a cave or abandoned places or Himalayan mountains, and towards the end of his life he moved to a cremation ground, surviving on little, peacefully awaiting his death.[168]

The Pashupatas have been particularly prominent inGujarat,Rajasthan,KashmirandNepal.The community is found in many parts of the Indian subcontinent.[180]In the late medieval era, Pashupatas Shaiva ascetics became extinct.[174][181]

Lakula Atimargi

[edit]This second division of the Atimarga developed from the Pashupatas. Their fundamental text too was the Pashupata Sutras. They differed from Pashupata Atimargi in that they departed radically from the Vedic teachings, respected no Vedic or social customs. He would walk around, for example, almost naked, drank liquor in public, and used a human skull as his begging bowl for food.[182]The Lakula Shaiva ascetic recognized no act nor words as forbidden, he freely did whatever he felt like, much like the classical depiction of his deity Rudra in ancient Hindu texts. However, according to Alexis Sanderson, the Lakula ascetic was strictly celibate and did not engage in sex.[182]

Secondary literature, such as those written by Kashmiri Ksemaraja, suggest that the Lakula had their canons on theology, rituals and literature onpramanas(epistemology). However, their primary texts are believed to be lost, and have not survived into the modern era.[182]

Grihastha and Sannyasi Shaiva: Mantramarga

[edit]"Mantramārga" (Sanskrit:मन्त्रमार्ग, "the path of mantras" ) has been the Shaiva tradition for both householders and monks.[166]It grew from the Atimarga tradition.[185]This tradition sought not just liberation fromDukkha(suffering, unsatisfactoriness), but special powers (siddhi) and pleasures (bhoga), both in this life and next.[186]Thesiddhiwere particularly the pursuit ofMantramargamonks, and it is this sub-tradition that experimented with a great diversity of rites, deities, rituals, yogic techniques and mantras.[185]Both the Mantramarga and Atimarga are ancient traditions, more ancient than the date of their texts that have survived, according to Sanderson.[185]Mantramārga grew to become a dominant form of Shaivism in this period. It also spread outside of India intoSoutheast Asia'sKhmer Empire,Java,BaliandCham.[187][188]

The Mantramarga tradition created theShaiva Agamasand Shaiva tantra (technique) texts. This literature presented new forms of ritual, yoga and mantra.[189]This literature was highly influential not just to Shaivism, but to all traditions of Hinduism, as well as to Buddhism and Jainism.[190]Mantramarga had both theistic and monistic themes, which co-evolved and influenced each other. The tantra texts reflect this, where the collection contains both dualistic and non-dualistic theologies. The theism in the tantra texts parallel those found in Vaishnavism and Shaktism.[191][192]Shaiva Siddhanta is a major subtradition that emphasized dualism during much of its history.[192]

Shaivism has had strong nondualistic (advaita) sub-traditions.[193][194]Its central premise has been that theAtman(Self) of every being is identical to Shiva, its various practices and pursuits directed at understanding and being one with the Shiva within. This monism is close but differs somewhat from the monism found inAdvaita Vedantaof Adi Shankara. Unlike Shankara's Advaita, Shaivism monist schools considerMayaas Shakti, or energy and creative primordial power that explains and propels the existential diversity.[193]

Srikantha, influenced byRamanuja,formulated ShaivaVishishtadvaita.[195]In this theology, Atman (Self) is not identical withBrahman,but shares with the Supreme all its qualities.Appayya Dikshita(1520–1592), an Advaita scholar, proposed pure monism, and his ideas influenced Shaiva in theKarnatakaregion. His Shaiva Advaita doctrine is inscribed on the walls of Kalakanthesvara temple in Adaiyappalam (Tiruvannamalai district).[196][197]

Shaiva Siddhanta

[edit]

TheŚaivasiddhānta( "the established doctrine of Shiva" ) is the earliestsampradaya(tradition, lineage) of Tantric Shaivism, dating from the 5th century.[192][198]The tradition emphasizes loving devotion to Shiva,[199]uses 5th to 9th-century Tamil hymns calledTirumurai.A key philosophical text of this sub-tradition was composed by 13th-centuryMeykandar.[200]This theology presents three universal realities: thepashu(individual Self), thepati(lord, Shiva), and thepasha(Self's bondage) through ignorance,karmaandmaya.The tradition teaches ethical living, service to the community and through one's work, loving worship, yoga practice and discipline, continuous learning and self-knowledge as means for liberating the individual Self from bondage.[200][201]

The tradition may have originated in Kashmir where it developed a sophisticated theology propagated by theologians Sadyojoti, Bhatta Nārāyanakantha and his son Bhatta Rāmakantha (c. 950–1000).[202]However, after the arrival of Islamic rulers in north India, it thrived in the south.[203]The philosophy ofShaiva Siddhanta,is particularly popular insouth India,Sri Lanka,MalaysiaandSingapore.[204]

The historic Shaiva Siddhanta literature is an enormous body of texts.[205]The tradition includes both Shiva and Shakti (goddess), but with a growing emphasis on metaphysical abstraction.[205]Unlike the experimenters of Atimarga tradition and other sub-traditions of Mantramarga, states Sanderson, the Shaiva Siddhanta tradition had no ritual offering or consumption of "alcoholic drinks, blood or meat". Their practices focussed on abstract ideas of spirituality,[205]worship and loving devotion to Shiva as SadaShiva, and taught the authority of the Vedas and Shaiva Agamas.[206][207]This tradition diversified in its ideas over time, with some of its scholars integrating a non-dualistic theology.[208]

Nayanars

[edit]

By the 7th century, theNayanars,a tradition of poet-saints in the bhakti tradition developed in ancientTamil Naduwith a focus on Shiva, comparable to that of the Vaisnava Alvars.[210]The devotionalTamilpoems of the Nayanars are divided into eleven collections together known asTirumurai,along with aTamilPuranacalled thePeriya Puranam.The first seven collections are known as theTevaramand are regarded by Tamils as equivalent to theVedas.[211]They were composed in the 7th century bySambandar,Appar,andSundarar.[212]

Tirumular(also spelledTirumūlārorTirumūlar), the author of theTirumantiram(also spelledTirumandiram) is considered by Tattwananda to be the earliest exponent of Shaivism in Tamil areas.[213]Tirumular is dated as 7th or 8th century by Maurice Winternitz.[214]TheTirumantiramis a primary source for the system of Shaiva Siddhanta, being the tenth book of its canon.[215]TheTiruvacakambyManikkavacagaris an important collection of hymns.[216]

Tantra Diksha traditions

[edit]The main element of all Shaiva Tantra is the practice ofdiksha,a ceremonial initiation in which divinely revealedmantrasare given to the initiate by aGuru.[217]

A notable feature of some "left tantra" ascetics was their pursuit ofsiddhis(supernatural abilities) andbala(powers), such as averting danger (santih) and the ability to harm enemies (abhicarah).[218][219][220]Ganachakras,ritual feasts, would sometimes be held in cemeteries and cremation grounds and featured possession by powerful female deities calledYoginis.[217][221]The cult of Yoginis aimed to gain special powers through esoteric worship of the Shakti or the feminine aspects of the divine. The groups included sisterhoods that participated in the rites.[221]

Some traditions defined special powers differently. For example, the Kashmiri tantrics explain the powers asanima(awareness than one is present in everything),laghima(lightness, be free from presumed diversity or differences),mahima(heaviness, realize one's limit is beyond one's own consciousness),prapti(attain, be restful and at peace with one's own nature),prakamya(forbearance, grasp and accept cosmic diversity),vasita(control, realize that one always has power to do whatever one wants),isitva(self lordship, a yogi is always free).[222]More broadly, the tantric sub-traditions sought nondual knowledge and enlightening liberation by abandoning all rituals, and with the help of reasoning (yuktih), scriptures (sastras) and the initiating Guru.[223][220]

Kashmir Shaivism

[edit]

Kashmir Shaivismis an influential tradition within Shaivism that emerged in Kashmir in the 1st millennium CE and thrived in early centuries of the 2nd millennium before the region was overwhelmed by the Islamic invasions from theHindu Kushregion.[224]The Kashmir Shaivism traditions contracted due to Islam except for their preservation byKashmiri Pandits.[225][226]The tradition experienced arevivalin the 20th century due especially to influence ofSwami Lakshmanjooand his students.[227]

Kashmir Shaivism has been a nondualistic school,[228][229]and is distinct from the dualistic Shaiva Siddhānta tradition that also existed in medieval Kashmir.[230][231][232]A notable philosophy of monistic Kashmiri Shaivism has been thePratyabhijnaideas, particularly those by the 10th century scholarUtpaladevaand 11th centuryAbhinavaguptaandKshemaraja.[233][234]Their extensive texts established the Shaiva theology and philosophy in anadvaita(monism) framework.[225][231]TheSiva Sutrasof 9th centuryVasuguptaand his ideas aboutSpandahave also been influential to this and other Shaiva sub-traditions, but it is probable that much older Shaiva texts once existed.[231][235]

A notable feature of Kashmir Shaivism was its openness and integration of ideas fromShaktism,VaishnavismandVajrayana Buddhism.[225]For example, one sub-tradition of Kashmir Shaivism adopts Goddess worship (Shaktism) by stating that the approach to god Shiva is through goddess Shakti. This tradition combined monistic ideas with tantric practices. Another idea of this school wasTrika,or modal triads of Shakti and cosmology as developed bySomanandain the early 10th century.[225][232][236]

Nath

[edit]

Nath:a Shaiva subtradition that emerged from a much older Siddha tradition based onYoga.[237]The Nath consider Shiva as "Adinatha" or the first guru, and it has been a small but notable and influential movement inIndiawhose devotees were called "Yogi" or "Jogi", given their monastic unconventional ways and emphasis on Yoga.[238][239][240]

Nath theology integrated philosophy fromAdvaita VedantaandBuddhismtraditions. Their unconventional ways challenged all orthodox premises, exploring dark and shunned practices of society as a means to understanding theology and gaining inner powers. The tradition traces itself to 9th or 10th centuryMatsyendranathand to ideas and organization developed byGorakshanath.[237]They combined both theistic practices such as worshipping goddesses and their historicGurusin temples, as well monistic goals of achieving liberation orjivan-muktiwhile alive, by reaching the perfect (siddha) state of realizing oneness of self and everything with Shiva.[241][237]

They formed monastic organisations,[237]and some of them metamorphosed into warrior ascetics to resist persecution during the Islamic rule of the Indian subcontinent.[242][243][244]

Lingayatism

[edit]

Lingayatism,also known as Veera Shaivism is a distinct Shaivite religious tradition inIndia.[246][247][248]It was founded by the 12th-century philosopher and statesmanBasavaand spread by his followers, calledSharanas.[249]

Lingayatism emphasizesqualified monismandbhakti(loving devotion) to Shiva, with philosophical foundations similar to those of the 11th–12th-century South Indian philosopherRamanuja.[246]Its worship is notable for the iconographic form ofIshtalinga,which the adherents wear.[250][251]Large communities of Lingayats are found in the south Indian state of Karnataka and nearby regions.[246][252][253]Lingayatism has its own theological literature with sophisticated theoretical sub-traditions.[254]

They were influential in the HinduVijayanagara Empirethat reversed the territorial gains of Muslim rulers, after the invasions of the Deccan region first byDelhi Sultanateand later other Sultanates. Lingayats consider their scripture to beBasava Purana,which was completed in 1369 during the reign of Vijayanagara rulerBukka Raya I.[255][256]Lingayat (Veerashaiva) thinkers rejected the custodial hold of Brahmins over theVedasand theshastras,but they did not outright reject the Vedic knowledge.[257][258]The 13th-century Telugu Virashaiva poetPalkuriki Somanatha,the author of the scripture of Lingayatism, for example asserted, "Virashaivism fully conformed to theVedasand the shastras. "[257][258]

Demography and Presence of believers

[edit]There are no census data available on demographic history or trends for the traditions within Hinduism.[259]Large Shaivite communities exist in the Southern Indian states ofTamil Nadu,Karnataka,Telangana,KeralaandAndhra Pradeshas well as inJammu & Kashmir,Himachal PradeshandUttrakhand.Substantial communities are also found inHaryana,Maharashtraand centralUttar Pradesh.[260][261]

According to Galvin Flood, Shaivism and Shaktism traditions are difficult to separate, as many Shaiva Hindus revere the goddess Shakti regularly.[262]The denominations of Hinduism, states Julius Lipner, are unlike those found in major religions of the world, because Hindu denominations are fuzzy with individuals revering gods and goddessespolycentrically,with many Shaiva and Vaishnava adherents recognizing Sri (Lakshmi), Parvati, Saraswati and other aspects of the goddess Devi. Similarly, Shakta Hindus revere Shiva and goddesses such as Parvati, Durga, Radha, Sita and Saraswati important in Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions.[263]

Influence

[edit]Shiva is a pan-Hindu god and Shaivism ideas onYogaand as the god of performance arts (Nataraja) have been influential on all traditions of Hinduism.

Shaivism was highly influential in southeast Asia from the late 6th century onwards, particularly the Khmer and Cham kingdoms of Indochina, and across the major islands of Indonesia such as Sumatra, Java and Bali.[264]This influence on classicalCambodia,VietnamandThailandcontinued when Mahayana Buddhism arrived with the same Indians.[265][266]

In Shaivism of Indonesia, the popular name for Shiva has beenBhattara Guru,which is derived from SanskritBhattarakawhich means "noble lord".[267]He is conceptualized as a kind spiritual teacher, the first of allGurusin Indonesian Hindu texts, mirroring the Dakshinamurti aspect of Shiva in the Indian subcontinent.[268]However, the Bhattara Guru has more aspects than the Indian Shiva, as the Indonesian Hindus blended their spirits and heroes with him. Bhattara Guru's wife in southeast Asia is the same Hindu deity Durga, who has been popular since ancient times, and she too has a complex character with benevolent and fierce manifestations, each visualized with different names such as Uma, Sri, Kali and others.[269][270]Shiva has been called Sadasiva, Paramasiva, Mahadeva in benevolent forms, and Kala, Bhairava, Mahakala in his fierce forms.[270]The Indonesian Hindu texts present the same philosophical diversity of Shaivism traditions found on the subcontinent. However, among the texts that have survived into the contemporary era, the more common are of those of Shaiva Siddhanta (locally also called Siwa Siddhanta, Sridanta).[271]

AsBhakti movementideas spread in South India, Shaivite devotionalism became a potent movement inKarnatakaandTamil Nadu.Shaivism was adopted by several ruling Hindu dynasties as the state religion (though other Hindu traditions, Buddhism and Jainism continued in parallel), including theChola,Nayaks(lingayats)[272]and theRajputs.A similar trend was witnessed in early medieval Indonesia with theMajapahitempire and pre-IslamicMalaya.[273][274]In the Himalayan Hindu kingdom of Nepal, Shaivism remained a popular form of Hinduism and co-evolved with Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.

Shaktism

[edit]The goddess tradition of Hinduism calledShaktismis closely related to Shaivism. In many regions of India, not only did the ideas of Shaivism influence the evolution of Shaktism, but Shaivism also itself was influenced by it and progressively subsumed the reverence for the divine feminine (Devi) as an equal and essential partner of divine masculine (Shiva).[275]The goddess Shakti in eastern states of India is considered the inseparable partner of God Shiva. According to Galvin Flood, the closeness between Shaivism and Shaktism traditions is such that these traditions of Hinduism are at times difficult to separate.[262]Some Shaiva worship in Shiva and Shakti temples.[8]

Smarta Tradition

[edit]Shiva is a part of theSmarta Tradition,sometimes referred to as Smartism, another tradition of Hinduism.[276]The Smarta Hindus are associated with theAdvaita Vedantatheology, and their practices include an interim step that incorporates simultaneous reverence for five deities, which includes Shiva along with Vishnu, Surya, Devi and Ganesha. This is called thePanchayatana puja.The Smartas thus accept the primary deity of Shaivism as a means to their spiritual goals.[26]

Philosophically, the Smarta tradition emphasizes that all idols (murti) are icons ofsagunaBrahman,a means to realizing the abstract Ultimate Reality called nirguna Brahman. The five or six icons are seen bySmartasas multiple representations of the oneSaguna Brahman(i.e., a personal God with form), rather than as distinct beings.[277][278]The ultimate goal in this practice is to transition past the use of icons, then follow a philosophical and meditative path to understanding the oneness of Atman (Self) and Brahman (metaphysical Ultimate Reality) – as "That art Thou".[276][279][280]

Panchayatana puja that incorporates Shiva became popular in medieval India and is attributed to 8th centuryAdi Shankara,[276][279]but archaeological evidence suggests that this practice long predates the birth of Adi Shankara. Many Panchayatana mandalas and temples have been uncovered that are from theGupta Empireperiod, and one Panchayatana set from the village of Nand (about 24 kilometers fromAjmer) has been dated to belong to theKushan Empireera (pre-300 CE).[281]According to James Harle, major Hindu temples from 1st millennium CE commonly embedded thepancayatanaarchitecture, fromOdishatoKarnatakatoKashmir.Large temples often present multiple deities in the same temple complex, while some explicitly include dual representations of deities such asHarihara(half Shiva, half Vishnu).[280]

Vaishnavism

[edit]Vaishnava texts reverentially mention Shiva. For example, theVishnu Puranaprimarily focuses on the theology of Hindu godVishnuand hisavatarssuch asKrishna,but it praisesBrahmaand Shiva and asserts that they are one with Vishnu.[283]The Vishnu Sahasranama in theMahabharatalist a thousand attributes and epithets of Vishnu. The list identifies Shiva with Vishnu.[284]

Reverential inclusion of Shaiva ideas and iconography are very common in major Vaishnava temples, such as Dakshinamurti symbolism of Shaiva thought is often enshrined on the southern wall of the main temple of major Vaishnava temples in peninsular India.[285]Hariharatemples in and outside the Indian subcontinent have historically combined Shiva and Vishnu, such as at the Lingaraj Mahaprabhu temple in Bhubaneshwar, Odisha. According to Julius Lipner, Vaishnavism traditions such asSri Vaishnavismembrace Shiva, Ganesha and others, not as distinct deities of polytheism, but as polymorphic manifestation of the same supreme divine principle, providing the devotee a polycentric access to the spiritual.[286]

Similarly, Shaiva traditions have reverentially embraced other gods and goddesses as manifestation of the same divine.[287]TheSkanda Purana,for example in section 6.254.100 states, "He who is Shiva is Vishnu, he who is Vishnu is Sadashiva."[288]

Sauraism (Sun deity)

[edit]The sun god calledSuryais an ancient deity of Hinduism, and several ancient Hindu kingdoms particularly in the northwest and eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent revered Surya. These devotees called Sauras once had a large corpus of theological texts, and Shaivism literature reverentially acknowledges these.[289]For example, the Shaiva textSrikanthiyasamhitamentions 85 Saura texts, almost all of which are believed to have been lost during the Islamic invasion and rule period, except for large excerpts found embedded in Shaiva manuscripts discovered in the Himalayan mountains. Shaivism incorporated Saura ideas, and the surviving Saura manuscripts such asSaurasamhitaacknowledge the influence of Shaivism, according to Alexis Sanderson, assigning "itself to the canon of Shaiva textVathula-Kalottara.[289]

Yoga movements

[edit]

Yoga and meditation have been an integral part of Shaivism, and it has been a major innovator of techniques such as those of Hatha Yoga.[290][291][292]Many major Shiva temples and Shaivatritha(pilgrimage) centers, as well as Shaiva texts, depict anthropomorphic iconography of Shiva as a giant statue wherein Shiva is a lone yogi meditating.[293][294]

In several Shaiva traditions such as the Kashmir Shaivism, anyone who seeks personal understanding and spiritual growth has been called aYogi.TheShivaSutras(aphorisms) of Shaivism teach yoga in many forms. According toMark Dyczkowski,yoga – which literally means "union" – to this tradition has meant the "realisation of our true inherent nature which is inherently greater than our thoughts can ever conceive", and that the goal of yoga is to be the "free, eternal, blissful, perfect, infinite spiritually conscious" one is.[295]

Many Yoga-emphasizing Shaiva traditions emerged in medieval India, who refined yoga methods in ways such as introducingHatha Yogatechniques. One such movement had been theNathYogis, a Shaivism sub-tradition that integrated philosophy fromAdvaita VedantaandBuddhismtraditions. It was founded byMatsyendranathand further developed byGorakshanath.[239][240][296]The texts of these Yoga emphasizing Hindu traditions present their ideas in Shaiva context.[note 8]

Hindu performance arts

[edit]Shiva is the lord of dance and dramatic arts in Hinduism.[298][299][300]This is celebrated in Shaiva temples asNataraja,which typically shows Shiva dancing in one of the poses in the ancient Hindu text on performance arts called theNatya Shastra.[299][301][302]

Dancing Shiva as a metaphor for celebrating life and arts is very common in ancient and medieval Hindu temples. For example, it is found inBadami cave temples,Ellora Caves,Khajuraho,Chidambaramand others. The Shaiva link to the performance arts is celebrated inIndian classical dancessuch asBharatanatyamandChhau.[303][304][305]

Buddhism

[edit]Buddhism and Shaivism have interacted and influenced each other since ancient times in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. Their Siddhas and esoteric traditions, in particular, have overlapped to an extent where Buddhists and Hindus worshipped in the same temple such as in theSeto Machindranath.In southeast Asia, the two traditions were not presented in competitive or polemical terms, rather as two alternate paths that lead to the same goals of liberation, with theologians disagreeing which of these is faster and simpler.[306]Scholars disagree whether a syncretic tradition emerged from Buddhism and Shaivism, or it was a coalition with free borrowing of ideas, but they agree that the two traditions co-existed peacefully.[307]

The earliest evidence of a close relationship between Shaivism and Buddhism comes from the archaeological sites and damaged sculptures from the northwest Indian subcontinent, such as Gandhara. These are dated to about the 1st-century CE, with Shiva depicted in Buddhist arts.[308][note 9]The Buddhist Avalokiteshvara is linked to Shiva in many of these arts,[309]but in others Shiva is linked to Bodhisattva Maitreya with he shown as carrying his own water pot like Vedic priests.[308]According to Richard Blurton, the ancient works show that the Bodhisattva of Compassion in Buddhism has many features in common with Shiva in Shaivism.[309]The Shaiva Hindu and Buddhist syncretism continues in the contemporary era in the island of Bali, Indonesia.[310]In Central Asian Buddhism, and its historic arts, syncretism and a shared expression of Shaivism, Buddhism and Tantra themes has been common. This is evdient in theKizil CavesinXin gian g,where there are numerous caves that depict Shiva in the buddhist shrines through wall paintings[311][312][313]

The syncretism between Buddhism and Shaivism was particularly marked in southeast Asia, but this was not unique, rather it was a common phenomenon also observed in the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, the south and the Himalayan regions.[90]This tradition continues in predominantly Hindu Bali Indonesia in the modern era, where Buddha is considered the younger brother of Shiva.[90][note 10]In the pre-Islamic Java, Shaivism and Buddhism were considered very close and allied religions, though not identical religions.[315][note 11]This idea is also found in the sculptures and temples in the eastern states of India and the Himalayan region. For example, Hindu temples in these regions showHarihara(half Shiva, half Vishnu) flanked by a standingBuddhaon its right and a standingSurya(Hindu Sun god) on left.[317][318]

On major festivals of Bali Hindus, such as theNyepi– a "festival of silence", the observations are officiated by both Buddhist and Shaiva priests.[90][319][320]

Jainism

[edit]Jainism co-existed with Shaiva culture since ancient times, particularly in western and southern India where it received royal support from Hindu kings of the Chaulukya, Ganga and Rashtrakuta dynasties.[321]In late 1st millennium CE, Jainism too developed a Shaiva-like tantric ritual culture with Mantra-goddesses.[321][322]These Jain rituals were aimed at mundane benefits usingjapas(mantra recitation) and making offerings intoHomafire.[321]

According to Alexis Sanderson, the link and development of Shaiva goddesses into Jaina goddess is more transparent than a similar connection between Shaivism and Buddhism.[323]The 11th-century Jain textBhairavapadmavatikalpa,for example, equates Padmavati of Jainism with Tripura-bhairavi of Shaivism and Shaktism. Among the major goddesses of Jainism that are rooted in Hindu pantheon, particularly Shaiva, include Lakshmi and Vagishvari (Sarasvati) of the higher world in Jain cosmology, Vidyadevis of the middle world, and Yakshis such as Ambika, Cakreshvari, Padmavati and Jvalamalini of the lower world according to Jainism.[321]

Shaiva-Shakti iconography is found in major Jain temples. For example, the Osian temple of Jainism near Jodhpur features Chamunda, Durga, Sitala, and a naked Bhairava.[324]While Shaiva and Jain practices had considerable overlap, the interaction between the Jain community and Shaiva community differed on the acceptance of ritual animal sacrifices before goddesses. Jain remained strictly vegetarian and avoided animal sacrifice, while Shaiva accepted the practice.[325]

Temples and pilgrimage

[edit]Shaiva Puranas, Agamas and other regional literature refer to temples by various terms such asMandir,Shivayatana,Shivalaya,Shambhunatha,Jyotirlingam,Shristhala,Chattraka,Bhavaggana,Bhuvaneshvara,Goputika,Harayatana,Kailasha,Mahadevagriha,Saudhalaand others.[326]In Southeast Asia Shaiva temples are calledCandi(Java),[327]Pura(Bali),[328]andWat(Cambodiaand nearby regions).[329][330]

Many of the Shiva-related pilgrimage sites such as Varanasi, Amarnath, Kedarnath, Somnath, and others are broadly considered holy in Hinduism. They are calledkṣétra(Sanskrit: क्षेत्र[331]). Akṣétrahas many temples, including one or more major ones. These temples and its location attracts pilgrimage called tirtha (or tirthayatra).[332]

Many of the historicPuranasliterature embed tourism guide to Shaivism-related pilgrimage centers and temples.[333]For example, theSkanda Puranadeals primarily withTirtha Mahatmyas(pilgrimage travel guides) to numerous geographical points,[333]but also includes a chapter stating that a temple andtirthais ultimately a state of mind and virtuous everyday life.[334][335]

Major rivers of the Indian subcontinent and their confluence (sangam), natural springs, origin of Ganges River (andpancha-ganga), along with high mountains such as Kailasha with Mansovar Lake are particularly revered spots in Shaivism.[336][337]Twelvejyotirlingasites across India have been particularly important pilgrimage sites in Shaivism representing the radiant light (jyoti) of infiniteness,[338][339][340]as perŚiva Mahāpurāṇa.[341]They areSomnatha,Mallikarjuna,Mahakaleshwar,Omkareshwar,Kedarnatha,Bhimashankar,Visheshvara,Trayambakesvara,Vaidyanatha,Nageshvara,RameshvaraandGrishneshwar.[337]Other texts mention five Kedras (Kedarnatha, Tunganatha, Rudranatha, Madhyamesvara and Kalpeshvara), five Badri (Badrinatha, Pandukeshvara, Sujnanien, Anni matha and Urghava), snow lingam of Amarnatha, flame of Jwalamukhi, all of the Narmada River, and others.[337]Kashi (Varanasi) is declared as particularly special in numerous Shaiva texts and Upanishads, as well as in the pan-HinduSannyasa Upanishadssuch as theJabala Upanishad.[342][343]

The earlyBhakti movementpoets of Shaivism composed poems about pilgrimage and temples, using these sites as metaphors for internal spiritual journey.[344][345]

See also

[edit]- Chaturdasa Devata

- Hindu denominations

- History of Shaivism

- Jangam Lingayat

- Shaiva Siddhanta

- Kashmiri Shaivism

Notes

[edit]- ^ab The ithyphallic representation of the erect shape connotes the very opposite in this context.[346]It contextualize "seminal retention" and practice ofcelibacy[347](illustration ofUrdhva Retas),[348][349]and represents Lakulisha as "he stands for complete complete control of the senses, and for the supreme carnal renunciation".[346]

- ^Kapalikas are alleged to smear their body with ashes from the cremation ground, revered the fierce Bhairava form of Shiva, engage in rituals with blood, meat, alcohol, and sexual fluids. However, states David Lorenzen, there is a paucity of primary sources on Kapalikas, and historical information about them is available from fictional works and other traditions who disparage them.[71][72]

- ^The Dunhuang caves in north China built from the 4th century onwards are predominantly about the Buddha, but some caves show the meditating Buddha with Hindu deities such as Shiva, Vishnu, Ganesha and Indra.[87]

- ^There is an overlap in this approach with those found in non-puranik tantric rituals.[97]

- ^Pashupatas have both Vedic-Puranik and non-Puranik sub-traditions.[95]

- ^Vasugupta is claimed by twoAdvaita(Monistic) Shaivism sub-traditions to be their spiritual founder.[128]

- ^ForŚvetāśvataraUpanishad as a systematic philosophy of Shaivism see:Chakravarti 1994,p. 9.

- ^For example:

[It will] be impossible to accomplish one's functions unless one is a master of oneself.

Therefore strive for self-mastery, seeking to win the way upwards.

To have self-mastery is to be a yogin (yogitvam). [v. 1–2]

[...]

Whatever reality he reaches through the Yoga whose sequence I have just explained,

he realizes there a state of consciousness whose object is all that pervades.

Leaving aside what remains outside he should use his vision to penetrate all [within].

Then once he has transcended all lower realities, he should seek the Shiva level. [v. 51–53]

[...]

How can a person whose awareness is overwhelmed by sensual experience stabilize his mind?

Answer: Shiva did not teach this discipline (sādhanam) for individuals who are not [already] disaffected. [v. 56–57]

[...]— Bhatta Narayanakantha,Mrigendratantra(paraphrased), Transl: Alexis Sanderson[297] - ^Some images show proto-Vishnu images.[308]

- ^Similarly, in Vaishnavism Hindu tradition, Buddha is considered one of theavatarsof Vishnu.[314]

- ^Medieval Hindu texts of Indonesia equate Buddha with Siwa (Shiva) and Janardana (Vishnu).[316]

References

[edit]- ^Bisschop 2020,pp. 15–16.

- ^abcdBisschop 2011.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 1.

- ^abJohnson, Todd M; Grim, Brian J (2013).The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography.John Wiley & Sons. p. 400.ISBN9781118323038.Archivedfrom the original on 9 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^abcdJones & Ryan 2006,p. 474.

- ^abFlood 1996,pp. 162–167.

- ^abcdeGanesh Tagare (2002), The Pratyabhijñā Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass,ISBN978-81-208-1892-7,pages 16–19

- ^abcFlood 2003,pp. 202–204.

- ^abcDavid Smith (1996), The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India, Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-48234-9,page 116

- ^abcdeMariasusai Dhavamony (1999), Hindu Spirituality, Gregorian University and Biblical Press,ISBN978-88-7652-818-7,pages 31–34 with footnotes

- ^abMark Dyczkowski (1989), The Canon of the Śaivāgama, Motilal Banarsidass,ISBN978-81-208-0595-8,pages 43–44

- ^"Chapter 1 Global Religious Populations"(PDF).January 2012. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 October 2013.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 66-70.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 1, 66-70.

- ^Flood 2003,pp. 208–214.

- ^Jan Gonda(1975).Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions.BRILL Academic. pp. 3–20, 35–36, 49–51.ISBN90-04-04330-6.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^"Introduction to Hinduism".Himalayan Academy. 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2015.Retrieved1 February2014.

- ^Apte 1965,p. 919.

- ^abMacdonell, p. 314.

- ^Chakravarti 1994,p. 28.

- ^abMonier Monier-Williams (1899),Sanskrit to English Dictionary with EtymologyArchived27 February 2017 at theWayback Machine,Oxford University Press, pages 1074–1076

- ^Chakravarti 1994,p. 21-22.

- ^Chakravarti 1994,p. 21-23.

- ^Apte 1965,p. 927.

- ^Flood 1996,p. 149.

- ^abFlood 1996,p. 17.

- ^Keay, p.xxvii.

- ^Julius J. Lipner(2009), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition, Routledge,ISBN978-0-415-45677-7,page 8; Quote: "(...) one need not be religious in the minimal sense described to be accepted as a Hindu by Hindus, or describe oneself perfectly validly as Hindu. One may bepolytheisticor monotheistic, monistic orpantheistic,even an agnostic, humanist oratheist,and still, be considered a Hindu. "

- ^Lester Kurtz (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace and Conflict,ISBN978-0123695031,Academic Press, 2008

- ^MK Gandhi,The Essence of HinduismArchived24 July 2015 at theWayback Machine,Editor: VB Kher, Navajivan Publishing, see page 3; According to Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu."

- ^For an overview of the Shaiva Traditions, see Flood, Gavin, "The Śaiva Traditions", Flood (2003), pp. 200–228.

- ^Tattwananda, p. 54.

- ^Gavin Flood (1997), An Introduction to Hinduism, p.152

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 66-106.

- ^For dating as fl. 2300–2000 BCE, decline by 1800 BCE, and extinction by 1500 BCE see: Flood (1996), p. 24.

- ^abcdefgFlood 2003,pp. 204–205.

- ^For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1in:Flood (1996), p. 29.

- ^For translation ofpaśupatias "Lord of Animals" see: Michaels, p. 312.

- ^Flood 1996,pp. 28–29.

- ^Mark Singleton(2010),Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice,Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-539534-1,pages 25–34

- ^Samuel 2008,p. 2–10.

- ^Asko Parpola(2009),Deciphering the Indus Script,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0521795661,pages 240–250

- ^Loeschner, Hans (2012)The Stūpa of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the GreatArchived20 December 2016 at theWayback Machine,Sino-Platonic Papers,No. 227 (July 2012); page 11

- ^abBopearachchi, O. (2007). Some observations on the chronology of the early Kushans.Res Orientales,17, 41–53

- ^Perkins, J. (2007). Three-headed Śiva on the Reverse of Vima Kadphises's Copper Coinage.South Asian Studies,23(1), 31–37

- ^abcFlood 2003,p. 205.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 66.

- ^abFlood 1996,p. 150.

- ^abChakravarti 1986,p. 69.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 66-69.

- ^Chakravarti 1994,pp. 70–71.

- ^Chakravarti 1986,p. 70.

- ^Laura Giuliano (2004)."Silk Road Art and Archaeology".Journal of the Institute of Silk Road Studies.10.Kamakura, Shiruku Rōdo Kenkyūjo: 61.Archivedfrom the original on 29 February 2020.Retrieved11 March2017.

- ^abFlood 1996,p. 154.

- ^George Cardona (1997).Pāṇini: A Survey of Research.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 277–278, 58 with note on Guleri.ISBN978-81-208-1494-3.

- ^[a] Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass,ISBN978-8120814684,pages 301–304;

[b] R G Bhandarkar (2001), Vaisnavism, Saivism and Minor Religious Systems, Routledge,ISBN978-8121509992,pages 106–111 - ^Robert Hume (1921), Shvetashvatara Upanishad, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 400–406 with footnotes

- ^Flood 1996,pp. 153–154.

- ^A Kunst, Some notes on the interpretation of the Ṥvetāṥvatara Upaniṣad, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 31, Issue 02, June 1968, pages 309–314;doi:10.1017/S0041977X00146531

- ^D Srinivasan (1997), Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes, Brill,ISBN978-9004107588,pages 96–97 and Chapter 9

- ^Stephen Phillips (2009),Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy,Columbia University Press,ISBN978-0-231-14485-8,Chapter 1

- ^Michael W. Meister (1984).Discourses on Siva: Proceedings of a Symposium on the Nature of Religious Imagery.University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 274–276.ISBN978-0-8122-7909-2.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2019.Retrieved12 March2017.

- ^abLorenzen 1987,pp. 6–20.

- ^"Early Strata of Śaivism in the Kathmandu Valley, Śivaliṅga Pedestal Inscriptions from 466–645 CE".Indo-Iranian Journal.59(4). Brill Academic Publishers: 309–362. 2016.doi:10.1163/15728536-05904001.

- ^Bakker, Hans (2014).The World of the Skandapurāṇa,pp. 2-5. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-27714-4.

- ^Ganguli, Kalyan Kumar (1988).Sraddh njali, studies in Ancient Indian History. D.C. Sircar Commemoration: Puranic tradition of Krishna.Sundeep Prakashan. p. 36.ISBN978-81-85067-10-0.

- ^Dandekar (1977)."Vaishnavism: an overview".In Jones, Lindsay (ed.).MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion.MacMillan (Reprinted in 2005). p. 9500.ISBN978-0028657332.

- ^abcBakker, Hans T. (12 March 2020).The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia.Barkhuis. pp. 98–99 and 93.ISBN978-94-93194-00-7.

- ^abDaniélou 1987,p. 128.

- ^Tattwananda 1984,p. 46.

- ^David N. Lorenzen (1972).The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Śaivite Sects.University of California Press. pp. xii, 4–5.ISBN978-0-520-01842-6.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved12 March2017.

- ^Flood 2003,pp. 212–213.

- ^Flood 2003,pp. 206–214.

- ^abSanderson 2009,pp. 61–62 with footnote 64.

- ^Group of Monuments at MahabalipuramArchived23 November 2019 at theWayback Machine,UNESCO World Heritage Sites; Quote: "It is known especially for its rathas (temples in the form of chariots), mandapas (cave sanctuaries), giant open-air reliefs such as the famous 'Descent of the Ganges', and the temple of Rivage, with thousands of sculptures to the glory of Shiva."

- ^abAlexis Sanderson (2014),The Saiva Literature,Journal of Indological Studies, Kyoto, Nos. 24 & 25, pages 1–113

- ^Ann R. Kinney, Marijke J. Klokke & Lydia Kieven 2003,p. 17.

- ^abBriggs 1951,pp. 230–249.

- ^abAlexis Sanderson 2004,pp. 349–352.

- ^Pratapaditya Pal; Stephen P. Huyler; John E. Cort; et al. (2016).Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent.University of California Press. pp. 61–62.ISBN978-0-520-28847-8.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2017.Retrieved26 March2017.

- ^abHeather Elgood (2000).Hinduism and the Religious Arts.Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 47–48.ISBN978-0-304-70739-3.Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2019.Retrieved26 March2017.

- ^Heather Elgood (2000).Hinduism and the Religious Arts.Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 143–167.ISBN978-0-304-70739-3.Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2019.Retrieved26 March2017.

- ^Wendy Doniger (2009), An Alternative Historiography for Hinduism, Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 2, Issue 1, pages 17–26, Quote: "Numerous Sanskrit texts and ancient sculptures (such as the Gudimallam linga from the third century BCE) define (...)"

- ^Srinivasan, Doris (1984). "Unhinging Śiva from the Indus civilization".Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland.116(1). Cambridge University Press: 77–89.doi:10.1017/s0035869x00166134.S2CID162904592.

- ^Kulke, Kesavapany & Sakhuja 2010.

- ^S. J. Vainker (1990).Caves of the Thousand Buddhas: Chinese Art from the Silk Route.British Museum Publications for the Trustees of the British Museum. p. 162.ISBN978-0-7141-1447-7.

- ^Edward L. Shaughnessy (2009).Exploring the Life, Myth, and Art of Ancient China.The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 70.ISBN978-1-4358-5617-2.

- ^Ann R. Kinney, Marijke J. Klokke & Lydia Kieven 2003,p. 21-25.

- ^Balinese peopleArchived17 April 2019 at theWayback Machine,Encyclopedia Britannica (2014)

- ^abcdeR. Ghose (1966), Saivism in Indonesia during the Hindu-Javanese period, The University of Hong Kong Press, pages 4–6, 14–16, 94–96, 160–161, 253

- ^Andrea Acri (2015). D Christian Lammerts (ed.).Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern and Early Modern Southeast Asia.Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 261–275.ISBN978-981-4519-06-9.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2017.Retrieved28 March2017.

- ^James Boon (1977).The Anthropological Romance of Bali 1597–1972: Dynamic Perspectives in Marriage and Caste, Politics and Religion.CUP Archive.ISBN0-521-21398-3.

- ^abAxel Michaels (2004).Hinduism: Past and Present.Princeton University Press. pp. 215–217.ISBN0-691-08952-3.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved12 March2017.

- ^abcSanderson 1988,pp. 660–704.

- ^abcdeFlood 2003,pp. 206–207.

- ^Flood 2003,pp. 205–207, 215–221.

- ^abFlood 2003,pp. 221–223.

- ^abFlood 2003,pp. 208–209.

- ^Flood 2003,pp. 210–213.

- ^Sanderson 1988,pp. 660–663, 681–690.

- ^Sanderson 1988,pp. 17–18.

- ^Mariasusai Dhavamony (1999).Hindu Spirituality.Gregorian Press. pp. 32–34.ISBN978-88-7652-818-7.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^abcdJan Gonda (1970).Visnuism and Sivaism: A Comparison.Bloomsbury Academic.ISBN978-1-4742-8080-8.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Christopher Partridge (2013).Introduction to World Religions.Fortress Press. p. 182.ISBN978-0-8006-9970-3.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Sanjukta Gupta (1 February 2013).Advaita Vedanta and Vaisnavism: The Philosophy of Madhusudana Sarasvati.Routledge. pp. 65–71.ISBN978-1-134-15774-7.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Lai Ah Eng (2008).Religious Diversity in Singapore.Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. p. 221.ISBN978-981-230-754-5.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2016.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002).Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives.Rodopi. p. 63.ISBN90-420-1510-1.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Stephen H Phillips (1995), Classical Indian Metaphysics, Columbia University Press,ISBN978-0812692983,page 332 with note 68

- ^Olivelle, Patrick (1992).The Samnyasa Upanisads.Oxford University Press. pp. 4–18.ISBN978-0195070453.

- ^abcGavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-43878-0,pages 162–167

- ^"Shaivas".Overview Of World Religions.Philtar.Archivedfrom the original on 22 February 2017.Retrieved13 December2017.

- ^Munavalli, Somashekar (2007).Lingayat Dharma (Veerashaiva Religion)(PDF).Veerashaiva Samaja of North America. p. 83. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 26 June 2013.Retrieved13 December2017.

- ^Prem Prakash (1998).The Yoga of Spiritual Devotion: A Modern Translation of the Narada Bhakti Sutras.Inner Traditions. pp. 56–57.ISBN978-0-89281-664-4.Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Frazier, J. (2013). "Bhakti in Hindu Cultures".The Journal of Hindu Studies.6(2). Oxford University Press: 101–113.doi:10.1093/jhs/hit028.

- ^Lisa Kemmerer; Anthony J. Nocella (2011).Call to Compassion: Reflections on Animal Advocacy from the World's Religions.Lantern. pp. 27–36.ISBN978-1-59056-281-9.Archivedfrom the original on 27 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Frederick J. Simoons (1998).Plants of Life, Plants of Death.University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 182–183.ISBN978-0-299-15904-7.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^K. Sivaraman (1973).Śaivism in Philosophical Perspective.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 336–340.ISBN978-81-208-1771-5.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^John A. Grimes, A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English, State University of New York Press,ISBN978-0791430675,page 238

- ^Flood 1996,p. 225.

- ^Eliott Deutsche (2000), in Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy Vol 4 (Editor: Roy Perrett), Routledge,ISBN978-0815336112,pages 245–248

- ^McDaniel, June (2004).Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls.Oxford University Press. pp. 89–91.ISBN978-0-19-534713-5.Archivedfrom the original on 4 January 2017.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Matthew James Clark (2006).The Daśanāmī-saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order.Brill. pp. 177–225.ISBN978-90-04-15211-3.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Hurley, Leigh; Hurley, Phillip (2012).Tantra, Yoga of Ecstasy: the Sadhaka's Guide to Kundalinin and the Left-Hand Path.Maithuna Publications. p. 5.ISBN9780983784722.

- ^Kim Skoog (1996). Andrew O. Fort; Patricia Y. Mumme (eds.).Living Liberation in Hindu Thought.SUNY Press. pp. 63–84, 236–239.ISBN978-0-7914-2706-4.Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Rajendra Prasad (2008).A Conceptual-analytic Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals.Concept. p. 375.ISBN978-81-8069-544-5.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2019.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^Sanderson, Alexis (2013)."The Impact of Inscriptions on the Interpretation of Early Śaiva Literature".Indo-Iranian Journal.56(3–4). Brill Academic Publishers: 211–244.doi:10.1163/15728536-13560308.

- ^abcFlood 2003,pp. 223–224.

- ^Ganesh Vasudeo Tagare (2002).The Pratyabhijñā Philosophy.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–4, 16–18.ISBN978-81-208-1892-7.Archivedfrom the original on 15 March 2017.Retrieved15 March2017.

- ^Mark S. G. Dyczkowski (1987).The Doctrine of Vibration: An Analysis of the Doctrines and Practices Associated with Kashmir Shaivism.State University of New York Press. pp. 17–25.ISBN978-0-88706-431-9.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Pathak 1960,pp. 11, 51–52.

- ^For dating to 400–200 BCE see: Flood (1996), p. 86.

- ^abcAyyangar, TRS (1953).Saiva Upanisads.Jain Publishing Co. (Reprint 2007).ISBN978-0895819819.

- ^Peter Heehs (2002), Indian Religions, New York University Press,ISBN978-0814736500,pages 60–88

- ^Olivelle, Patrick (1998).Upaniṣads.Oxford University Press. pp.11–14.ISBN978-0192835765.

- ^Deussen, Paul (1997).Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1.Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.pp. 247–268 with footnotes.ISBN978-8120814677.Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2016.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Deussen, Paul (1997).Sixty Upanishads of the Veda.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 791–794.ISBN978-8120814677.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Chester G Starr (1991), A History of the Ancient World, 4th Edition, Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0195066289,page 168

- ^Peter Heehs (2002), Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience, New York University Press,ISBN978-0814736500,pages 85–86

- ^Deussen, Paul (1997).Sixty Upanishads of the Veda.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 773–777.ISBN978-8120814677.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Ignatius Viyagappa (1980), G.W.F. Hegel's Concept of Indian Philosophy, Gregorian University Press,ISBN978-8876524813,pages 24-25

- ^H Glasenapp (1974), Die Philosophie der Inder, Kröner,ISBN978-3520195036,pages 259–260

- ^Deussen, Paul (1997).Sixty Upanishads of the Veda.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 779–782.ISBN978-8120814677.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Hattangadi, Sunder (2000)."बृहज्जाबालोपनिषत् (Brihat-Jabala Upanishad)"(PDF)(in Sanskrit).Archived(PDF)from the original on 22 July 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Deussen, Paul (1997).Sixty Upanishads of the Veda.Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 789–790.ISBN978-8120814677.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Kramrisch 1994a,p. 274-286.

- ^AM Sastri (2001).Dakshinamurti stotra of Sri Sankaracharya and Dakshinamurti Upanishad with Sri Sureswaracharya's Manasollasa and Pranava Vartika.Samata (Original: 1920). pp. 153–158.ISBN978-8185208091.OCLC604013222.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Hattangadi, Sunder (2000)."शरभोपनिषत् (Sharabha Upanishad)"(in Sanskrit).Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2017.Retrieved13 March2017.

- ^Beck, Guy (1995).Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 133–134, 201–202.ISBN978-8120812611.

- ^Ayyangar, TRS (1953).Saiva Upanisads.Jain Publishing Co. (Reprint 2007). pp. 193–199.ISBN978-0895819819.

- ^Ayyangar, TRS (1953).Saiva Upanisads.Jain Publishing Co. (Reprint 2007). pp. 165–192.ISBN978-0895819819.