Samaria

Samaria | |

|---|---|

Hills near the ruins ofSamaria | |

| Coordinates:32°16′30″N35°11′24″E/ 32.275°N 35.190°E | |

| Part of | West Bank,Palestine |

| Highest elevation | 1,016 m (3,333 ft) (Tall Asur(Ba'al Hazor)) |

| Designation | السامرة,שֹׁומְרוֹן |

Samaria(/səˈmæriə,-ˈmɛəriə/) is theHellenizedform of the Hebrew nameShomron(Hebrew:שֹׁמְרוֹן),[1]used as a historical andbiblicalname for the centralregionofIsrael,bordered byJudeato the south andGalileeto the north.[2][3]The region is known to thePalestiniansin Arabic under two names,Samirah(Arabic:السَّامِرَة,as-Sāmira), andMount Nablus(جَبَل نَابُلُس,Jabal Nābulus).

The first-century historianJosephusset theMediterranean Seaas its limit to the west, and theJordan Riveras its limit to the east.[3]Its territory largely corresponds to thebiblicalallotments of thetribe of Ephraimand the western half ofManasseh.It includes most of the region of the ancientKingdom of Israel,which was north of theKingdom of Judah.The border between Samaria and Judea is set at the latitude ofRamallah.[4]

The name "Samaria" is derived from theancient city of Samaria,capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel.[5][6][7]The name Samaria likely began being used for the entire kingdom not long after the town of Samaria had become Israel's capital, but it is first documented after its conquest by theNeo-Assyrian Empire,which incorporated the land into the province ofSamerina.[5]

Samaria was used to describe the northern midsection of the land in theUN Partition Plan for Palestinein 1947. It became the administrative term in1967,when theWest Bankwasdefined by Israeli officialsas theJudea and Samaria Area,[8]of which the entire area north of theJerusalem Districtis termed as Samaria. In 1988,Jordanceded its claim of the area to thePalestine Liberation Organization(PLO).[9]In 1994, control of Areas 'A' (full civil and security control by thePalestinian Authority) and 'B' (Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli–Palestinian security control) were transferred by Israel to the Palestinian Authority. The Palestinian Authority and the international community do not recognize the term "Samaria"; in modern times, the territory is generally known as part of the West Bank.[10]

Etymology

[edit]

According to theHebrew Bible,the Hebrew name "Shomron" (Hebrew:שֹׁומְרוֹן) is derived from the individual (or clan)Shemer(Hebrew:שֶׁמֶר), from whomKing Omri(ruled 880s–870s BCE) purchased the hill on which he built his new capital city ofShomron.[11][12]

The fact that the mountain was called Shomeron when Omri bought it may indicate that the correct etymology of the name is to be found more directly in theSemiticroot for "guard", hence its initial meaning would have been "watch mountain". In the earliercuneiforminscriptions, Samaria is designated under the name of "Bet Ḥumri" ("the house of Omri"); but in those ofTiglath-Pileser III(ruled 745–727 BCE) and later it is called Samirin, after itsAramaicname,[13]Shamerayin.[6]

Historical boundaries

[edit]Northern kingdom to Hellenistic period

[edit]InNelson's Encyclopaedia(1906–1934), the Samaria region in the three centuries followingthe fall of the northern kingdom of Israel,i.e. during theAssyrian,Babylonian,andPersianperiods, is described as a "province" that "reached from the [Mediterranean] sea to the Jordan Valley".[14]

Roman-period definition

[edit]The classical Roman-Jewish historianJosephuswrote:

(4) Now as to the country of Samaria, it lies between Judea and Galilee; it begins at a village that is in the great plain calledGinea,and ends at theAcrabbenetoparchy,and is entirely of the same nature with Judea; for both countries are made up of hills and valleys, and are moist enough for agriculture, and are very fruitful. They have abundance of trees, and are full of autumnal fruit, both that which grows wild, and that which is the effect of cultivation. They are not naturally watered by many rivers, but derive their chief moisture from rain-water, of which they have no want; and for those rivers which they have, all their waters are exceeding sweet: by reason also of the excellent grass they have, their cattle yield more milk than do those in other places; and, what is the greatest sign of excellency and of abundance, they each of them are very full of people. (5) In the limits of Samaria and Judea lies the village Anuath, which is also named Borceos. This is the northern boundary of Judea.[3]

During the first century, the boundary between Samaria and Judea passed eastward ofAntipatris,along the deep valley which had Beth Rima (nowBani Zeid al-Gharbia) and Beth Laban (today'sal-Lubban al-Gharbi) on its southern, Judean bank; then it passed Anuath and Borceos, identified byCharles William Wilson(1836–1905) as the ruins of'Aina and Khirbet Berkit;and reached theJordan Valleynorth ofAcrabbimandSartaba.[15]Tall Asuralso stands at that boundary.

Geography

[edit]The area known as the hills of Samaria is bounded by theJezreel Valley(north); by theJordan Rift Valley(east); by theCarmelRidge (northwest); by theSharon plain(west); and by theJerusalemmountains (south).[16][dubious–discuss]

The Samarian hills are not very high, seldom reaching the height of over 800 meters. Samaria's climate is more hospitable than the climate further south.

There is no clear division between the mountains of southern Samaria and northern Judea.[2]

History

[edit]

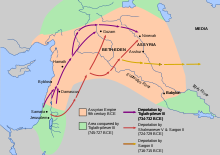

Over time, the region has been controlled by numerous different civilizations, includingCanaanites,Israelites,Neo-Assyrians,Babylonians,Persians,Seleucids,Hasmoneans,Romans,Byzantines,Arabs,Crusaders,andOttoman Turks.[17]

Israelite tribes and kingdoms

[edit]According to theHebrew Bible,theIsraelitescaptured the region known as Samaria from theCanaanitesand assigned it to theTribe of Joseph.The southern part of Samaria was then known asMount Ephraim.After the death ofKing Solomon(c. 931 BC), the northern tribes, includingEphraimandMenashe,separated themselves politically from the southern tribes and established the separateKingdom of Israel.Initially its capital wasTirzahuntil the time of King Omri (c. 884 BC), who built the city ofSamariaand made it his capital. Samaria functioned as the capital of the Kingdom of Israel (the "Northern Kingdom" ) until its fall to the Assyrians in the 720s. Hebrew prophets condemned Samaria for its "ivory houses" and luxury palaces displaying pagan riches.[18]

The archaeological record suggests that Samaria experienced significant settlement growth in Iron Age II (fromc.950 BC). Archaeologists estimate that there were 400 sites, up from 300 during the previous Iron Age I (c.1200 BC onwards). The people dwelt ontells,in small villages, farms, and forts, and in the cities ofShechem,Samaria and Tirzah in northern Samaria.Zertalestimated that about 52,000 people inhabited the Manasseh Hill in northern Samaria prior to the Assyrian deportations. According to botanists, the majority of Samaria's forests were torn down during the Iron Age II, and were replaced by plantations and agricultural fields. Since then, few oak forests have grown in the region.[19]

Assyrian period

[edit]

In the 720s, theconquest of SamariabyShalmaneser Vof theNeo-Assyrian Empire,which culminated in the three-year siege of thecapital city of Samaria,saw the territory annexed as the Assyrian province ofSamerina.[20]The siege has been tentatively dated to 725 or 724 BC, with its resolution in 722 BC, near the end of Shalmaneser's reign.[20]The first documented mention of the province of Samerina is from the reign of Shalmaneser V's successorSargon II.This is also the first documented instance where a name derived from "Samaria", the capital city, was used for the entire region, although it is thought likely that this practice was already in place.[5]

Following the Assyrian conquest,Sargon IIclaimed in Assyrian records to have deported 27,280 people to various places throughout the empire, mainly toGuzanain the Assyrian heartland, as well as to the cities of theMedesin the eastern part of the empire (modern-day Iran).[21][22][23]The deportations were part of a standardresettlement policy of the Neo-Assyrian Empireto deal with defeated enemy peoples.[24]The resettled people were generally treated well as valued members of the empire and transported together with their families and belongings.[25][26][27]At the same time, people from other parts of the empire were resettled in the depopulated Samerina.[28]The resettlement is also called theAssyrian captivityinJewish historyand provides the basis for the narrative of theTen Lost Tribes.[24]

Babylonian and Persian periods

[edit]

According to many scholars, archaeological excavations at Mount Gerizim indicate that a Samaritan temple was built there in the first half of the 5th century BCE.[29]The date of the schism between Samaritans and Jews is unknown, but by the early 4th century BCE the communities seem to have had distinctive practices and communal separation.[citation needed]Much of the anti-Samaritan polemic in the Hebrew Bible and extra-biblical texts (such as Josephus) originate from this point and on.[30]

Hellenistic period

[edit]During theHellenistic period,Samaria was largely divided between a Hellenizing faction based around the town of Samaria and a pious faction in Shechem and surrounding rural areas, led by the High Priest.

Samaria was a largely autonomous province nominally dependent on theSeleucid Empire.However, the province gradually declined as theMaccabeanmovement andHasmonean Judeagrew stronger.[31]The transfer of three districts of Samaria—Ephraim,LodandRamathaim—under the control of Judea in 145 BCE as part of an agreement betweenJonathan ApphusandDemetrius IIis one indication of this decline.[31][32]Around 110 BCE, the decline of Hellenistic Samaria was complete, when the JewishHasmonean rulerJohn Hyrcanusdestroyed the cities of Samaria and Shechem, as well as the city and temple on Mount Gerizim.[31][33]Only a few stone remnants of the Samaritan temple exist today.

Roman period

[edit]In 6 CE, Samaria became part of the Roman province ofIudaea,following the death of KingHerod the Great.

Southern Samaria reached a peak in settlement during the early Roman period (63 BCE–70 CE), partly as a result of theHasmonean dynasty's settlement efforts. The impact of theJewish–Roman warsis archaeologically evident in Jewish-inhabited areas of southern Samaria, as many sites were destroyed and left abandoned for extended periods of time. After theFirst Jewish-Roman War,the Jewish population of the area decreased by around 50%, whereas after theBar Kokhba revolt,it was completely wiped in many areas. According to Klein, the Roman authorities replaced the Jews with a population from the nearby provinces ofSyria,Phoenicia,andArabia.[34][35]An apparent new wave of settlement growth in southern Samaria, most likely by non-Jews, can be traced back to the late Roman and Byzantine eras.[36][19]

New Testament references

[edit]This sectionusestexts from within a religion or faith systemwithout referring tosecondary sourcesthat critically analyze them.(April 2023) |

TheNew Testamentmentions Samaria inLuke17:11–2,[37]in the miraculoushealing of the ten lepers,which took place on the border of Samaria and Galilee.John4:1-26[38]records Jesus' encounter atJacob's Wellwith the woman of Sychar, in which he declares himself to be the Messiah. In Acts 8:1,[39]it is recorded that the early community of disciples of Jesus began to bepersecutedin Jerusalem and were 'scattered throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria'.Philipwent down to thecity of Samariaand preached and healed the sick there.[40]In the time ofJesus,Iudaeaof the Romans was divided into thetoparchiesof Judea, Samaria, Galilee and theParalia.Samaria occupied the centre ofIudaea.[41](Iudaeawas later renamedSyria Palaestinain 135, following theBar Kokhba revolt.) In theTalmud,Samaria is called the "land of the Cuthim".

Byzantine period

[edit]Following the bloody suppression of theSamaritan Revolts(mostly in 525 CE and 555 CE) against theByzantine Empire,which resulted in death, displacement, andconversion to Christianity,the Samaritan population dramatically decreased. In the central parts of Samaria, the vacuum left by departing Samaritans was filled by nomads who gradually becamesedentarized.[42]

The Byzantine period is considered the peak of settlement in Samaria, as in other regions of the country.[43]Based on historical sources and archeological data, theManasseh Hill surveyorsconcluded that Samaria's population during the Byzantine period was composed of Samaritans, Christians, and a minority of Jews.[44]The Samaritan population was mainly concentrated in the valleys of Nablus and to the north as far asJeninandKfar Othenai;they did not settle south of the Nablus-Qalqiliya line. Christianity slowly made its way into Samaria, even after the Samaritan revolts. With the exception of Neapolis, Sebastia, and a small cluster of monasteries in central and northern Samaria, most of the population of the rural areas remained non-Christian.[45]In southwestern Samaria, a significant concentration of churches and monasteries was discovered, with some of them built on top of citadels from the late Roman period. Magen raised the hypothesis that many of these were used by Christian pilgrims, and filled an empty space in the region whose Jewish population was wiped out in the Jewish–Roman wars.[46][19]

Early Muslim, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman periods

[edit]Following theMuslim conquest of the Levant,and throughout theearly Islamic period,Samaria underwent a process ofIslamizationas a result of waves of conversion among the remaining Samaritan population, along with the migration of Muslims into the area.[47][48][49]Evidence implies that a large number of Samaritans converted underAbbasidandTulunidrule, as a result of droughts, earthquakes, religious persecution, high taxes, and anarchy.[48][50]By the mid-Middle Ages,the Jewish writer and explorerBenjamin of Tudelaestimated that only around 1,900 Samaritans remained inPalestineandSyria.[51]

Ottoman Period

[edit]During theOttoman Period,the northern part of Samaria belonged to the TurabayEmirate (1517–1683), which encompassed also theJezreel Valley,Haifa,Jenin,Beit She'an Valley,northernJabal Nablus,Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe,and the northern part of theSharon plain.[52][53]The areas south of Jenin, includingNablusitself and its hinterland up to theYarkon River,formed a separate district called the District of Nablus.[54]

British Mandate

[edit]During theGreat War,Palestine was wrested by the armies of theBritish Empirefrom theOttoman Empireand in theaftermath of the warit was entrusted to theUnited Kingdomto administer as aLeague of Nationsmandated territory[55]Samaria was the name of one of theadministrative districtsof Palestine for part of this period. The1947 UN partition plancalled for the Arab state to consist of several parts, the largest of which was described as "the hill country of Samaria and Judea."[56]

Jordanian period

[edit]As a result of the1948 Arab–Israeli War,most of the territory was unilaterally incorporated asJordanian-controlled territory, and was administered as part of the West Bank (west of the Jordan river).

Israeli administration

[edit]The Jordanian-held West Bank was captured andhas been occupied by Israelsince the 1967Six-Day War.Jordanceded its claims in the West Bank (except for certain prerogatives in Jerusalem) to thePLOin November 1988, later confirmed by theIsrael–Jordan Treaty of Peaceof 1994. In the 1994Oslo accords,thePalestinian Authoritywas established and given responsibility for the administration over some of the territory of West Bank (Areas 'A' and 'B').

Samaria is one of several standard statistical districts utilized by theIsrael Central Bureau of Statistics.[57]"The Israeli CBS also collects statistics on the rest of the West Bank and the Gaza District. It has produced various basic statistical series on the territories, dealing with population, employment, wages, external trade, national accounts, and various other topics."[58]The Palestinian Authority however useNablus,Jenin,Tulkarm,Qalqilya,Salfit,RamallahandTubasgovernoratesas administrative centers for the same region.

TheShomron Regional Councilis the local municipal government that administers the smaller Israeli towns (settlements) throughout the area. The council is a member of the network of regional municipalities spread throughout Israel.[59]Elections for the head of the council are held every five years by Israel's ministry of interior, all residents over age 17 are eligible to vote. In special elections held in August 2015Yossi Daganwas elected as head of the Shomron Regional Council.[60]

Israeli settlements in the West Bank are considered by mostin the international community to be illegal under international law,but others including the United States and Israeli governments dispute this.[61]In September 2016, the Town Board of theAmericanTown of Hempsteadin theState of New York,led by CouncilmanBruce Blakemanentered into a partnership agreement with theShomron Regional Council,led byYossi Dagan,as part of an anti-Boycott, Divestment and Sanctionscampaign.[62]

Archaeological sites

[edit]Ancient city of Samaria/Sebaste

[edit]

The ancient site ofSamaria-Sebaste covers the hillside overlooking the West Bank village ofSebastiaon the eastern slope of the hill.[63]Remains have been found from theCanaanite,Israelite,Hellenistic,Roman(includingHerodian) andByzantineperiods.[64]

Archaeological finds from Roman-era Sebaste, a site that was rebuilt and renamed by Herod the Great in 30 BC, include a colonnaded street, a temple-lined acropolis, and a lower city, whereJohn the Baptistis believed to have been buried.[65]

The Harvard excavation of Samaria, which began in 1908, was headed by EgyptologistGeorge Andrew Reisner.[66]The findings included Hebrew, Aramaic, cuneiform and Greek inscriptions, as well as pottery remains, coins, sculpture, figurines, scarabs and seals, faience, amulets, beads and glass.[67]The joint British-American-Hebrew University excavation continued underJohn Winter Crowfootin 1931–35, during which time some of the chronology issues were resolved. The round towers lining the acropolis were found to be Hellenistic, the street of columns was dated to the 3–4th century, and 70 inscribed potsherds were dated to the early 8th century.[68]

In 1908–1935, remains of luxury furniture made of wood and ivory were discovered in Samaria, representing the Levant's most important collection of ivory carvings from the early first millennium BC. Despite theories of theirPhoenicianorigin, some of the letters serving as fitter's marks are inHebrew.[18]

As of 1999 three series of coins have been found that confirmSinuballatwas a governor of Samaria. Sinuballat is best known as an adversary ofNehemiahfrom theBook of Nehemiahwhere he is said to have sided withTobiah the AmmoniteandGeshem the Arabian.All three coins feature a warship on the front, likely derived from earlierSidoniancoins. The reverse side depicts the Persian King in hiskandysrobe facing down alionthat is standing on its hind legs.[69]

Other ancient sites

[edit]- TheBull Site,anIron Icult site

- Tel DothannearJenin,identified with biblical Dothan

- Khirbet Kheibar,inMeithalun,ancient tell which was inhabited from the Middle Bronze Age to Medieval times

- Khirbet Kurkush,site of an ancient Samaritan or Jewish settlement with a notable necropolis

- Khirbet Samara,site of a notable ancient Samaritan synagogue

- Nablusarea:

- Mount Gerizim,the religious epicenter ofSamaritanism,site of an ancient Samaritan temple, and Samaritan and Byzantine ruins

- Mount Ebal site,Iron Age remains onMount Ebal,seen by many scholars as an early Israelite cultic site

- Tell Balata,identified as biblicalShechem

- Khirbet Seilun/Tel Shiloh, identified withShiloh (biblical city)

- Tell el-Far'ah (North), identified with biblicalTirzah,the third capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel.

Samaritans

[edit]TheSamaritans(Hebrew: Shomronim) are anethnoreligious groupnamed after and descended from ancient Semitic inhabitants of Samaria, since theAssyrian exileof the Israelites, according to2 Kings 17and first-century historianJosephus.[70]Religiously, the Samaritans are adherents ofSamaritanism,anAbrahamic religionclosely related toJudaism.Based on theSamaritan Torah,Samaritans claim their worship is the true religion of the ancient Israelites prior to theBabylonian exile,preserved by those who remained behind. Their temple was built atMount Gerizimin the middle of the 5th century BCE, and was destroyed under theHasmoneankingJohn HyrcanusofJudeain 110 BCE, although their descendants still worship among its ruins. The antagonism between Samaritans and Jews is important in understanding the Bible'sNew Testamentstories of the "Samaritan woman at the well"and"Parable of the Good Samaritan".The modern Samaritans, however, see themselves as co-equals in inheritance to the Israelite lineage through Torah, as do the Jews, and are not antagonistic to Jews in modern times.[71]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Samaria".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.HarperCollins Publishers. 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 23 November 2022.Retrieved23 November2022.

- ^ab"Samaria - historical region, Palestine".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved31 May2018.

- ^abcJosephus Flavius."Jewish War,book 3, chapter 3:4-5 ".Fordham.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 29 April 2023.Retrieved31 December2012– via Ancient History Sourcebook: Josephus (37 – after 93 CE): Galilee, Samaria, and Judea in the First Century CE.

- ^The New Encyclopaedia Britannica:Macropaedia, 15th edition, 1987, volume 25, "Palestine", p. 403

- ^abcMills & Bullard 1990.

- ^ab"Online Etymology Dictionary".etymonline.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-08.Retrieved2014-01-28.

- ^"Open Collections Program: Expeditions and Discoveries, Harvard Expedition to Samaria, 1908–1910".ocp.hul.harvard.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-08.Retrieved2012-02-25.

- ^Emma Playfair (1992).International Law and the Administration of Occupied Territories: Two Decades of Israeli Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.Oxford University Press. p. 41.

On 17 December 1967, the Israeli military government issued an order stating that "the term 'Judea and Samaria region' shall be identical in meaning for all purposes... to the term 'the West Bank Region'". This change in terminology, which has been followed in Israeli official statements since that time, reflected a historic attachment to these areas and rejection of a name that implied Jordanian sovereignty over them.

- ^Kifner, John (1 August 1988)."Hussein surrenders claims on West Bank to the P.L.O.; U.S. peace plan in jeopardy; Internal Tensions".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 6 December 2011.Retrieved12 February2017.

- ^Neil Caplan (19 September 2011).The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories.John Wiley & Sons. pp. 18–.ISBN978-1-4443-5786-8.

- ^1 Kings 16:24

- ^"This Side of the River Jordan; On Language".Philologos.Forward. 22 September 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2011.Retrieved26 September2010.

- ^Singer, Isidore;et al., eds. (1901–1906)..The Jewish Encyclopedia.New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^Finley, John H.,ed. (October 1926)."Samaria".Nelson's perpetual loose-leaf encyclopaedia: an international work of reference.Vol. X. New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons. p. 550.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2022.Retrieved13 December2020– via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^James Hastings (editor),A Dictionary of the Bible,Volume III: (Part II: O - Pleiades), "Palestine: Geography", p.652,University Press of the Pacific, 2004,ISBN978-1-4102-1727-1

- ^"Samaria | historical region, Palestine | Britannica".britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved23 March2022.

- ^"Open Collections Program: Expeditions and Discoveries, Harvard Expedition to Samaria, 1908–1910".ocp.hul.harvard.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-08.Retrieved2012-02-25.

- ^ab"The Ivories from Samaria: Complete Catalogue, Stylistic Classification, Iconographical Analysis, Cultural-Historical Evaluation".research-projects.uzh.ch.Archived fromthe originalon 21 March 2018.

- ^abcדר, שמעון (2019)."הכלכלה הכפרית של השומרון בימי קדם".Judea and Samaria Research Studies(28): 5–44.doi:10.26351/JSRS/28-1/1.S2CID239322097.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-25.Retrieved2023-02-25.

- ^abYamada & Yamada 2017,pp. 408–409.

- ^Reid 1908.

- ^Elayi 2017,p. 50.

- ^Radner 2018,0:51.

- ^abMark 2014.

- ^Radner 2017,p. 210.

- ^Dalley 2017,p. 528.

- ^Frahm 2017,pp. 177–178.

- ^Gottheil et al. 1906.

- ^Magen, Yitzhak (2007)."The Dating of the First Phase of the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim in the Light of the Archaeological Evidence".In Oded Lipschitz; Gary N. Knoppers; Rainer Albertz (eds.).Judah and Judeans in the Fourth Century BC.Eisenbrauns.ISBN978-1-57506-130-6.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-11-29.Retrieved2022-01-18.

- ^L. Matassa, J. Macdonald; et al. (2007). "Samaritans". InBerenbaum, Michael;Skolnik, Fred(eds.).Encyclopaedia Judaica(2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 718–740.ISBN978-0-02-866097-4. As quoted byDepartment of Near Eastern Studies, University of MichiganArchived2021-09-20 at theWayback MachineandEncyclopediaArchived2022-01-18 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcDušek, Jan (27 October 2011),"Administration of Samaria in the Hellenistic Period",Samaria, Samarians, Samaritans,De Gruyter, pp. 76–77,doi:10.1515/9783110268201.71,ISBN978-3-11-026820-1,archivedfrom the original on 11 April 2023,retrieved11 April2023

- ^Raviv, Dvir (3 July 2019)."Granting of the Toparchies of Ephraim, Ramathaim and Lod to Hasmonean Judea".Tel Aviv.46(2): 267–285.doi:10.1080/03344355.2019.1650500.ISSN0334-4355.S2CID211674477.

- ^See: Jonathan Bourgel, "The Destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus: A ReconsiderationArchived2022-03-18 at theWayback Machine",JBL135/3 (2016), pp. 505-523;[1]Archived2019-06-20 at theWayback Machine.See also idem,"The Samaritans during the Hasmonean Period: The Affirmation of a Discrete Identity?"Archived2022-01-19 at theWayback MachineReligions 2019, 10(11), 628.

- ^קליין, א' (2011).היבטים בתרבות החומרית של יהודה הכפרית בתקופה הרומית המאוחרת(135–324 לסה "נ).עבודת דוקטור, אוניברסיטת בר-אילן. עמ' 314–315. (Hebrew)

- ^שדמן, ע' (2016).בין נחל רבה לנחל שילה: תפרוסת היישוב הכפרי בתקופות ההלניסטית, הרומית והביזנטית לאור חפירות וסקרים.עבודת דוקטור, אוניברסיטת בר-אילן. עמ' 271–275. (Hebrew)

- ^Finkelstein, I. 1993. The Southern Samarian Hills Survey. In E. Stern (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, Carta, Vol. 4, pp. 1314.

- ^Luke 17:11–20

- ^John 4:1–26

- ^Acts 8:1

- ^Acts 8:4–8

- ^John 4:4

- ^Ellenblum, Ronnie (2010).Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-511-58534-0.OCLC958547332.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-10.Retrieved2023-02-05.

From the data given above it can be concluded that the Muslim population of Central Samaria, during the early Muslim period, was not an autochthonous population which had converted to Christianity. They arrived there either by way of migration or as a result of a process of sedentarization of the nomads who had filled the vacuum created by the departing Samaritans at the end of the Byzantine period [...] To sum up: in the only rural region in Palestine in which, according to all the written and archeological sources, the process of Islamization was completed already in the twelfth century, there occurred events consistent with the model propounded by Levtzion and Vryonis: the region was abandoned by its original sedentary population and the subsequent vacuum was apparently filled by nomads who, at a later stage, gradually became sedentarized

- ^זרטל, א' (1992).סקר הר מנשה.קער שכם, כרך ראשון. תל-אביב וחיפה: אוניברסיטת חיפה ומשרד הביטחון. (Hebrew) 63–62.

- ^זרטל, א' (1996).סקר הר מנשה. העמקים המזרחיים וספר המדבר, כרך שני.תל-אביב וחיפה: אוניברסיטת חיפה ומשרד הביטחון. 93–91 (Hebrew)

- ^די סגני, ל' (2002). מרידות השומרונים בארץ-ישראל הביזנטית. בתוך א' שטרן וח' אשל (עורכים),ספר השומרונים.ירושלים: יד יצחק בן-צבי, רשות העתיקות, המנהל האזרחי ליהודה ושומרון קצין מטה לארכיאולוגיה, עמ' 454–480. (Hebrew)

- ^מגן, י' 2002.השומרונים בתקופה הרומית – הביזנטית. בתוך א' שטרן וח' אשל (עורכים),ספר השומרונים.ירושלים: יד יצחק בן-צבי, רשות העתיקות, המנהל האזרחי ליהודה ושומרון קצין מטה לארכיאולוגיה, עמ' 213–244. (Hebrew)

- ^לוי-רובין, מילכה; Levy-Rubin, Milka (2006)."The Influence of the Muslim Conquest on the Settlement Pattern of Palestine during the Early Muslim Period / הכיבוש כמעצב מפת היישוב של ארץ-ישראל בתקופה המוסלמית הקדומה".Cathedra: For the History of Eretz Israel and Its Yishuv / קתדרה: לתולדות ארץ ישראל ויישובה(121): 53–78.ISSN0334-4657.JSTOR23407269.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-05.Retrieved2023-02-05.

- ^abM. Levy-Rubin, "New evidence relating to the process of Islamization in Palestine in the Early Muslim Period - The Case of Samaria", in:Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient,43 (3), pp. 257–276, 2000,Springer

- ^Fattal, A. (1958).Le statut légal des non-Musulman en pays d'Islam,Beyrouth: Imprimerie Catholique, pp. 72–73.

- ^לוי-רובין, מילכה (2006). שטרן, אפרים; אשל, חנן (eds.).ספר השומרונים[Book of the Samaritans; The Continuation of the Samaritan Chronicle of Abu l-Fath] (in Hebrew) (2 ed.). ירושלים: יד יצחק בן צבי, רשות העתיקות, המנהל האזרחי ליהודה ושומרון: קצין מטה לארכיאולוגיה. pp. 562–586.ISBN978-965-217-202-0.

- ^Alan David Crown, Reinhard Pummer, Abraham Tal (eds.),A Companion to Samaritan Studies,Mohr Siebeck, 1993 pp.70-71.

- ^al-Bakhīt, Muḥammad ʻAdnān; al-Ḥamūd, Nūfān Rajā (1989)."Daftar mufaṣṣal nāḥiyat Marj Banī ʻĀmir wa-tawābiʻihā wa-lawāḥiqihā allatī kānat fī taṣarruf al-Amīr Ṭarah Bāy sanat 945 ah".worldcat.org.Amman: Jordanian University. pp. 1–35.Retrieved15 May2023.

- ^Marom, Roy (2023)."Lajjun: Forgotten Provincial Capital in Ottoman Palestine".Levant.55(2): 218–241.doi:10.1080/00758914.2023.2202484.S2CID258602184.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-18.Retrieved2023-05-10.

- ^Doumani, Beshara (12 October 1995).Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900.University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-20370-9.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2023.Retrieved10 May2023.

- ^The Mandate for Palestine. (24 July 1922). League of Nations Council. Retrieved 23 June 2021 fromthe Israeli Ministry of Foreign AffairsArchived2021-06-24 at theWayback Machine

- ^"UN partition resolution".Archived fromthe originalon 29 October 2006.

- ^"Israel Central Bureau of Statistics".Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2012.

- ^"Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs".Archivedfrom the original on 2005-12-08.Retrieved2005-12-05.

- ^"The Center for Regional Councils in Israel".Website.Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2008.

- ^Hebrew."Shomron Regional Council Website".Archivedfrom the original on 2016-01-06.Retrieved2015-12-28.

- ^"The Geneva Convention".BBC News.10 December 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 12 May 2019.Retrieved27 November2010.

- ^Lazaroff, Tovah (16 September 2016)."In anti-BDS stand, Hempstead New York signs sister city pact with settler council".Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2022.Retrieved24 July2017.

- ^Michael Hamilton Burgoyne and Mahmoud Hawari (19 May 2005)."Bayt al-Hawwari, ahawshHouse in Sabastiya ".Levant.37.Council for British Research in the Levant, London: 57–80.doi:10.1179/007589105790088913.S2CID162363298.Archivedfrom the original on 29 February 2012.Retrieved14 September2007.

- ^"Holy Land Blues".Al-Ahram Weekly.5–11 January 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 11 March 2006.Retrieved14 September2007.

- ^Wiener, Noah (6 April 2013)."Spurned Samaria: Site of the capital of the Kingdom of Israel blighted by neglect".Biblical Archaeology Society.Archivedfrom the original on 8 February 2014.Retrieved23 January2014.

- ^The Archaeology of Palestine,W.F. Albright, 1960, p. 34

- ^Albright, W. F. (24 July 2017). "Recent Progress in Palestinian Archaeology: Samaria-Sebaste III and Hazor I".Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.150(150): 21–25.doi:10.2307/1355880.JSTOR1355880.S2CID163393362.

- ^Albright, pp.39–40

- ^Edelman, Diana Vikander.The Origins of the Second Temple: Persian Imperial Policy and the Rebuilding of Jerusalem.Equinox. p. 41.

- ^Josephus,Jewish Antiquities9.277–91

- ^"Keepers: Israelite Samaritan Identity Since Joshua bin Nun".Israelite Samaritan Information Institute.26 May 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved11 February2017.

Sources

[edit]- Dalley, Stephanie(2017). "Assyrian Warfare". In E. Frahm (ed.).A Companion to Assyria.Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-1-444-33593-4.

- Elayi, Josette (2017).Sargon II, King of Assyria.Atlanta: SBL Press.ISBN978-1628371772.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "The Neo-Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE)". In E. Frahm (ed.).A Companion to Assyria.Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-1-444-33593-4.

- Gottheil, Richard; Ryssel, Victor; Jastrow, Marcus; Levias, Caspar (1906)."Captivity, or Exile, Babylonian".Jewish Encyclopedia.Vol. 3. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-10-21.Retrieved2023-08-15.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014)."Sargon II".World History Encyclopedia.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2021.Retrieved9 February2020.

- Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey, eds. (1990).Mercer Dictionary of the Bible.Mercer University Press. pp. 788–789.ISBN978-0-86554-373-7.Retrieved31 May2018.

Sargon... named the new province, which included what formerly was Israel,Samerina.Thus the territorial designation is credited to the Assyrians and dated to that time; however, "Samaria" probably long before alteratively designated Israel when Samaria became the capital.

- Radner, Karen(2017). "Economy, Society, and Daily Life in the Neo-Assyrian Period". In E. Frahm (ed.).A Companion to Assyria.Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-1-444-33593-4.

- Radner, Karen (2018).Focus on Population Management(video). Organising an Empire: The Assyrian Way.Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.Archived fromthe originalon 9 May 2018.Retrieved9 May2018– viaCoursera.

- Reid, George (1908)."Captivities of the Israelites".The Catholic Encyclopedia.New York:Robert Appleton Company.

- Yamada, Keiko; Yamada, Shiego (2017)."Shalmaneser V and His Era, Revisited".In Baruchi-Unna, Amitai; Forti, Tova; Aḥituv, Shmuel; Ephʿal, Israel; Tigay, Jeffrey H. (eds.)."Now It Happened in Those Days": Studies in Biblical, Assyrian, and Other Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Mordechai Cogan on His 75th Birthday.Vol. 2. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.ISBN978-1575067612.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-02-09.Retrieved2023-08-15.

Further reading

[edit]- Becking, B. (1992).The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and Archaeological Study.Leiden; New York: E. J. Brill.ISBN978-90-04-09633-2.

- Franklin, N. (2003). "The Tombs of the Kings of Israel".Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins.119(1): 1–11.

- Franklin, N. (2004). "Samaria: from the Bedrock to the Omride Palace".Levant.36:189–202.doi:10.1179/lev.2004.36.1.189.S2CID162217071.

- Park, Sung Jin (2012). "A New Historical Reconstruction of the Fall of Samaria".Biblica.93(1): 98–106.

- Rainey, A. F. (November 1988). "Toward a Precise Date for the Samaria Ostraca".Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.272(272): 69–74.doi:10.2307/1356786.JSTOR1356786.S2CID163297693.

- Stager, L. E. (February–May 1990). "Shemer's Estate".Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.277/278 (277): 93–107.doi:10.2307/1357375.JSTOR1357375.S2CID163576333.

- Tappy, R. E. (2006). "The Provenance of the Unpublished Ivories from Samaria", pp. 637–56 in"I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times" (Ps 78:2b): Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday,A. M. Maeir and P. de Miroschedji, eds. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Tappy, R. E. (2007). "The Final Years of Israelite Samaria: Toward a Dialogue Between Texts and Archaeology", pp. 258–79 inUp to the Gates of Ekron: Essays on the Archaeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymour Gitin,S. White Crawford, A. Ben-Tor, J. P. Dessel, W. G. Dever, A. Mazar, and J. Aviram, eds. Jerusalem: The W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and the Israel Exploration Society.

External links

[edit]- .Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 108.

- Vailhé, Siméon (1912)..Catholic Encyclopedia.Vol. 13.