Saturn

| |||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsætərn/[1] | ||||||||||||

Named after | Saturn | ||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Saturnian/səˈtɜːrniən/,[2]Cronian[3]/ Kronian[4]/ˈkroʊniən/[5] | ||||||||||||

| Symbol | |||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[6] | |||||||||||||

| EpochJ2000.0 | |||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 1,514.50 million km (10.1238 AU) | ||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 1,352.55 million km (9.0412 AU) | ||||||||||||

| 1,433.53 million km (9.5826 AU) | |||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0565 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 378.09 days | |||||||||||||

Averageorbital speed | 9.68 km/s (6.01 mi/s) | ||||||||||||

| 317.020°[8] | |||||||||||||

| Inclination | |||||||||||||

| 113.665° | |||||||||||||

| 2032-Nov-29[10] | |||||||||||||

| 339.392°[8] | |||||||||||||

| Knownsatellites | 146with formal designations; innumerable additionalmoonlets.[11][12] | ||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics[6] | |||||||||||||

| 58,232 km (36,184 mi)[b]

9.1402 Earths | |||||||||||||

Equatorialradius |

| ||||||||||||

Polarradius |

| ||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.09796 | ||||||||||||

| Circumference | 365882.4km (227348.8mi) (equatorial)[13] | ||||||||||||

| Volume |

| ||||||||||||

| Mass |

| ||||||||||||

Meandensity | 0.687g/cm3(0.0248lb/cu in)[c] 0.1246Earths | ||||||||||||

| 0.22[15] | |||||||||||||

| 35.5 km/s (22.1 mi/s)[b] | |||||||||||||

| 10 h 32 m 36 s; 10.5433 hours,[16]10 h 39 m; 10.7 hours[7] | |||||||||||||

| 10h33m38s+1m52s −1m19s [17][18] | |||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity | 9.87 km/s (6.13 mi/s; 35,500 km/h)[b] | ||||||||||||

| 26.73°(to orbit) | |||||||||||||

North poleright ascension | 40.589°;2h42m21s | ||||||||||||

North poledeclination | 83.537° | ||||||||||||

| Albedo | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| −0.55[23]to +1.17[23] | |||||||||||||

| −9.7[24] | |||||||||||||

| 14.5″ to 20.1″ (excludes rings) | |||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[6] | |||||||||||||

Surfacepressure | 140 kPa[25] | ||||||||||||

| 59.5 km (37.0 mi) | |||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | |||||||||||||

Saturnis the sixthplanetfrom theSunand the second-largest in theSolar System,afterJupiter.It is agas giantwith an average radius of about nine-and-a-half times that ofEarth.[26][27]It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 times more massive.[28][29][30]Even though Saturn is nearly the size of Jupiter, Saturn has less than one-third of Jupiter's mass. Saturn orbits the Sun at a distance of 9.59AU(1,434 millionkm) with anorbital periodof 29.45 years.

Saturn's interior is thought to be composed of a rocky core, surrounded by a deep layer ofmetallic hydrogen,an intermediate layer ofliquid hydrogenandliquid helium,and finally, a gaseous outer layer. Saturn has a pale yellow hue due toammoniacrystals in its upper atmosphere. Anelectrical currentwithin the metallic hydrogen layer is thought to give rise to Saturn's planetarymagnetic field,which is weaker than Earth's, but which has amagnetic moment580 times that of Earth due to Saturn's larger size. Saturn's magnetic field strength is around one-twentieth of Jupiter's.[31]The outeratmosphereis generally bland and lacking in contrast, although long-lived features can appear.Wind speedson Saturn can reach 1,800 kilometres per hour (1,100 miles per hour).

The planet has a bright and extensivering systemcomposed mainly of ice particles, with a smaller amount of rocky debris anddust.At least146 moons[32]are known to orbit the planet, of which 63 are officially named; this does not include the hundreds ofmoonletsin its rings.Titan,Saturn's largest moon and the second largest in the Solar System, is larger (while less massive) than the planetMercuryand is the only moon in the Solar System to have a substantial atmosphere.[33]

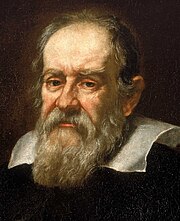

Name and symbol

Saturn is named after the Romangod of wealth and agricultureand father of Jupiter. Itsastronomical symbol(![]() )has been traced back to the GreekOxyrhynchus Papyri,where it can be seen to be a Greekkappa-rholigature with ahorizontal stroke,as an abbreviation forΚρονος(Cronus), the Greek name for the planet (

)has been traced back to the GreekOxyrhynchus Papyri,where it can be seen to be a Greekkappa-rholigature with ahorizontal stroke,as an abbreviation forΚρονος(Cronus), the Greek name for the planet (![]() ).[34]It later came to look like a lower-case Greeketa,with the cross added at the top in the 16th century to Christianize this pagan symbol.

).[34]It later came to look like a lower-case Greeketa,with the cross added at the top in the 16th century to Christianize this pagan symbol.

The Romans named the seventh day of the weekSaturday,Sāturni diēs( "Saturn's Day" ), for the planet Saturn.[35]

Physical characteristics

Saturn is agas giantcomposed predominantly of hydrogen and helium. It lacks a definite surface, though it is likely to have a solid core.[36]Saturn's rotation causes it to have the shape of anoblate spheroid;that is, it isflattenedat thepolesandbulgesat itsequator.Its equatorial radius is more than 10% larger than its polar radius: 60,268 km versus 54,364 km (37,449 mi versus 33,780 mi).[6]Jupiter,Uranus,andNeptune,the other giant planets in the Solar System, are also oblate but to a lesser extent. The combination of the bulge and rotation rate means that the effective surface gravity along the equator,8.96 m/s2,is 74% of what it is at the poles and is lower than the surface gravity of Earth. However, the equatorialescape velocityof nearly36 km/sis much higher than that of Earth.[37]

Saturn is the only planet of the Solar System that is less dense than water—about 30% less.[38]Although Saturn'scoreis considerably denser than water, the averagespecific densityof the planet is0.69 g/cm3due to the atmosphere. Jupiter has 318 timesEarth's mass,[39]and Saturn is 95 times Earth's mass.[6]Together, Jupiter and Saturn hold 92% of the total planetary mass in the Solar System.[40]

Internal structure

Despite consisting mostly of hydrogen and helium, most of Saturn's mass is not in thegasphase,because hydrogen becomes anon-ideal liquidwhen the density is above0.01 g/cm3,which is reached at a radius containing 99.9% of Saturn's mass. The temperature, pressure, and density inside Saturn all rise steadily toward the core, which causes hydrogen to be a metal in the deeper layers.[40]

Standard planetary models suggest that the interior of Saturn is similar to that of Jupiter, having a small rocky core surrounded by hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of variousvolatiles.[41]Analysis of the distortion shows that Saturn is substantially more centrally condensed thanJupiterand therefore contains a significantly larger amount of material denser thanhydrogennear its centre. Saturn's central regions contain about 50% hydrogen by mass, while Jupiter's contain approximately 67% hydrogen.[42]

This core is similar in composition to Earth, but is more dense. The examination of Saturn'sgravitational moment,in combination with physical models of the interior, has allowed constraints to be placed on the mass of Saturn's core. In 2004, scientists estimated that the core must be 9–22 times the mass of Earth,[43][44]which corresponds to a diameter of about 25,000 km (16,000 mi).[45]However, measurements of Saturn's rings suggest a much more diffuse core with a mass equal to about 17 Earths and a radius equal to around 60% of Saturn's entire radius.[46]This is surrounded by a thicker liquidmetallic hydrogenlayer, followed by a liquid layer of helium-saturatedmolecular hydrogenthat gradually transitions to a gas with increasing altitude. The outermost layer spans about 1,000 km (620 mi) and consists of gas.[47][48][49]

Saturn has a hot interior, reaching 11,700 °C (21,100 °F) at its core, and radiates 2.5 times more energy into space than it receives from the Sun. Jupiter'sthermal energyis generated by theKelvin–Helmholtz mechanismof slowgravitational compression,but such a process alone may not be sufficient to explain heat production for Saturn, because it is less massive. An alternative or additional mechanism may be the generation of heat through the "raining out" of droplets of helium deep in Saturn's interior. As the droplets descend through the lower-density hydrogen, the process releases heat byfrictionand leaves Saturn's outer layers depleted of helium.[50][51]These descending droplets may have accumulated into a helium shell surrounding the core.[41]Rainfalls ofdiamondshave been suggested to occur within Saturn, as well as in Jupiter[52]andice giantsUranus and Neptune.[53]

Atmosphere

The outer atmosphere of Saturn contains 96.3% molecular hydrogen and 3.25% helium by volume.[54]The proportion of helium is significantly deficient compared to the abundance of this element in the Sun.[41]The quantity of elements heavier than helium (metallicity) is not known precisely, but the proportions are assumed to match the primordial abundances from theformation of the Solar System.The total mass of these heavier elements is estimated to be 19–31 times the mass of Earth, with a significant fraction located in Saturn's core region.[55]

Trace amounts of ammonia,acetylene,ethane,propane,phosphine,andmethanehave been detected in Saturn's atmosphere.[56][57][58]The upper clouds are composed of ammonia crystals, while the lower level clouds appear to consist of eitherammonium hydrosulfide(NH4SH) or water.[59]Ultraviolet radiationfrom the Sun causes methanephotolysisin the upper atmosphere, leading to a series ofhydrocarbonchemical reactions with the resulting products being carried downward byeddiesanddiffusion.Thisphotochemical cycleis modulated by Saturn's annual seasonal cycle.[58]Cassiniobserved a series of cloud features found in northern latitudes, nicknamed the "String of Pearls". These features are cloud clearings that reside in deeper cloud layers.[60]

Cloud layers

Saturn's atmosphere exhibits a banded pattern similar to Jupiter's, but Saturn's bands are much fainter and are much wider near the equator. The nomenclature used to describe these bands is the same as on Jupiter. Saturn's finer cloud patterns were not observed until the flybys of theVoyagerspacecraft during the 1980s. Since then, Earth-basedtelescopyhas improved to the point where regular observations can be made.[61]

The composition of the clouds varies with depth and increasing pressure. In the upper cloud layers, with temperatures in the range of 100–160 K and pressures extending between 0.5–2bar,the clouds consist of ammonia ice. Waterice cloudsbegin at a level where the pressure is about 2.5 bar and extend down to 9.5 bar, where temperatures range from 185 to 270 K. Intermixed in this layer is a band of ammonium hydrosulfide ice, lying in the pressure range 3–6 bar with temperatures of 190–235 K. Finally, the lower layers, where pressures are between 10 and 20 bar and temperatures are 270–330 K, contains a region of water droplets with ammonia in aqueous solution.[62]

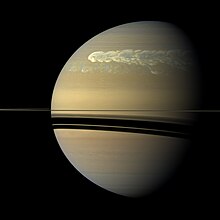

Saturn's usually bland atmosphere occasionally exhibits long-lived ovals and other features common on Jupiter. In 1990, theHubble Space Telescopeimaged an enormous white cloud near Saturn's equator that was not present during theVoyagerencounters, and in 1994 another smaller storm was observed. The 1990 storm was an example of aGreat White Spot,a short-lived phenomenon that occurs once every Saturnian year, roughly every 30 Earth years, around the time of the northern hemisphere'ssummer solstice.[63]Previous Great White Spots were observed in 1876, 1903, 1933, and 1960, with the 1933 storm being the best observed.[64]The latest giant storm was observed in 2010. In 2015, researchers usedVery Large Arraytelescope to study Saturnian atmosphere, and reported that they found "long-lasting signatures of all mid-latitude giant storms, a mixture of equatorial storms up to hundreds of years old, and potentially an unreported older storm at 70°N".[65]

The winds on Saturn are the second fastest among the Solar System's planets, after Neptune's.Voyagerdata indicate peak easterly winds of 500 m/s (1,800 km/h).[66]In images from theCassinispacecraft during 2007, Saturn's northern hemisphere displayed a bright blue hue, similar to Uranus. The color was most likely caused byRayleigh scattering.[67]Thermographyhas shown that Saturn's south pole has a warmpolar vortex,the only known example of such a phenomenon in the Solar System.[68]Whereas temperatures on Saturn are normally −185 °C, temperatures on the vortex often reach as high as −122 °C, suspected to be the warmest spot on Saturn.[68]

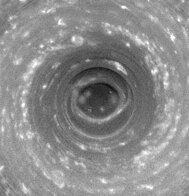

Hexagonal cloud patterns

A persistinghexagonalwave pattern around the north polar vortex in the atmosphere at about 78°N was first noted in theVoyagerimages.[69][70][71]The sides of the hexagon are each about 14,500 km (9,000 mi) long, which is longer than the diameter of the Earth.[72]The entire structure rotates with a period of10h39m24s(the same period as that of the planet's radio emissions) which is assumed to be equal to the period of rotation of Saturn's interior.[73]The hexagonal feature does not shift in longitude like the other clouds in the visible atmosphere.[74]The pattern's origin is a matter of much speculation. Most scientists think it is astanding wavepattern in the atmosphere. Polygonal shapes have been replicated in the laboratory through differential rotation of fluids.[75][76]

HSTimaging of the south polar region indicates the presence of ajet stream,but no strong polar vortex nor any hexagonal standing wave.[77]NASAreported in November 2006 thatCassinihad observed a "hurricane-like "storm locked to the south pole that had a clearly definedeyewall.[78][79]Eyewall clouds had not previously been seen on any planet other than Earth. For example, images from theGalileospacecraft did not show an eyewall in theGreat Red Spotof Jupiter.[80]

The south pole storm may have been present for billions of years.[81]This vortex is comparable to the size of Earth, and it has winds of 550 km/h.[81]

Magnetosphere

Saturn has an intrinsicmagnetic fieldthat has a simple, symmetric shape—a magneticdipole.Its strength at the equator—0.2gauss(20μT)—is approximately one twentieth of that of the field around Jupiter and slightly weaker than Earth's magnetic field.[31]As a result, Saturn'smagnetosphereis much smaller than Jupiter's.[82]

WhenVoyager 2entered the magnetosphere, thesolar windpressure was high and the magnetosphere extended only 19 Saturn radii, or 1.1 million km (684,000 mi),[83]although it enlarged within several hours, and remained so for about three days.[84]Most probably, the magnetic field is generated similarly to that of Jupiter—by currents in the liquid metallic-hydrogen layer called a metallic-hydrogen dynamo.[82]This magnetosphere is efficient at deflecting thesolar windparticles from the Sun. The moon Titan orbits within the outer part of Saturn's magnetosphere and contributes plasma from theionizedparticles in Titan's outer atmosphere.[31]Saturn's magnetosphere, likeEarth's,producesaurorae.[85]

Orbit and rotation

The average distance between Saturn and the Sun is over 1.4 billion kilometers (9AU). With an average orbital speed of 9.68 km/s,[6]it takes Saturn 10,759 Earth days (or about29+1⁄2years)[86]to finish one revolution around the Sun.[6]As a consequence, it forms a near 5:2mean-motion resonancewith Jupiter.[87]The elliptical orbit of Saturn is inclined 2.48° relative to theorbital planeof the Earth.[6]Theperihelion and apheliondistances are, respectively, 9.195 and 9.957 AU, on average.[6][88]The visible features on Saturn rotate at different rates depending on latitude, and multiple rotation periods have been assigned to various regions (as in Jupiter's case).

Astronomers use three different systems for specifying the rotation rate of Saturn.System Ihas a period of10h14m00s(844.3°/d) and encompasses the Equatorial Zone, the South Equatorial Belt, and the North Equatorial Belt. The polar regions are considered to have rotation rates similar toSystem I.All other Saturnian latitudes, excluding the north and south polar regions, are indicated asSystem IIand have been assigned a rotation period of10h38m25.4s(810.76°/d).System IIIrefers to Saturn's internal rotation rate. Based onradio emissionsfrom the planet detected byVoyager 1andVoyager 2,[89]System III has a rotation period of10h39m22.4s(810.8°/d). System III has largely superseded System II.[90]

A precise value for the rotation period of the interior remains elusive. While approaching Saturn in 2004,Cassinifound that the radio rotation period of Saturn had increased appreciably, to approximately10h45m45s±36s.[91][92]An estimate of Saturn's rotation (as an indicated rotation rate for Saturn as a whole) based on a compilation of various measurements from theCassini,Voyager,andPioneerprobes is10h32m35s.[93]Studies of the planet'sC Ringyield a rotation period of10h33m38s+1m52s

−1m19s .[17][18]

In March 2007, it was found that the variation in radio emissions from the planet did not match Saturn's rotation rate. This variance may be caused by geyser activity on Saturn's moonEnceladus.The water vapor emitted into Saturn's orbit by this activity becomes charged and creates a drag upon Saturn's magnetic field, slowing its rotation slightly relative to the rotation of the planet.[94][95][96]

An apparent oddity for Saturn is that it does not have any knowntrojan asteroids.These are minor planets that orbit the Sun at the stableLagrangian points,designated L4and L5,located at 60° angles to the planet along its orbit. Trojan asteroids have been discovered forMars,Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune.Orbital resonancemechanisms, includingsecular resonance,are believed to be the cause of the missing Saturnian trojans.[97]

Natural satellites

Saturn has 146 knownmoons,63 of which have formal names.[12][11]It is estimated that there are another100±30outer irregular moons larger than 3 km (2 mi) in diameter.[98]In addition, there is evidence of dozens to hundreds ofmoonletswith diameters of 40–500 meters in Saturn's rings,[99]which are not considered to be true moons.Titan,the largest moon, comprises more than 90% of the mass in orbit around Saturn, including the rings.[100]Saturn's second-largest moon,Rhea,may have a tenuousring system of its own,[101]along with a tenuousatmosphere.[102][103][104]

Many of the other moons are small: 131 are less than 50 km in diameter.[105]Traditionally, most of Saturn's moons have been named afterTitansof Greek mythology. Titan is the only satellite in theSolar Systemwith a majoratmosphere,[106][107]in which a complexorganic chemistryoccurs. It is the only satellite withhydrocarbon lakes.[108][109]

On 6 June 2013, scientists at theIAA-CSICreported the detection ofpolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsin theupper atmosphereof Titan, apossible precursor for life.[110]On 23 June 2014, NASA claimed to have strong evidence thatnitrogenin the atmosphere of Titan came from materials in theOort cloud,associated withcomets,and not from the materials that formed Saturn in earlier times.[111]

Saturn's moonEnceladus,which seems similar in chemical makeup to comets,[112]has often been regarded as a potentialhabitatformicrobial life.[113][114][115][116]Evidence of this possibility includes the satellite's salt-rich particles having an "ocean-like" composition that indicates most of Enceladus's expelledicecomes from the evaporation of liquid salt water.[117][118][119]A 2015 flyby byCassinithrough a plume on Enceladus found most of the ingredients to sustain life forms that live bymethanogenesis.[120]

In April 2014, NASA scientists reported the possible beginning of a new moon within theA Ring,which was imaged byCassinion 15 April 2013.[121]

Planetary rings

Saturn is probably best known for the system ofplanetary ringsthat makes it visually unique.[48]The rings extend from 6,630 to 120,700 kilometers (4,120 to 75,000 mi) outward from Saturn's equator and average approximately 20 meters (66 ft) in thickness. They are composed predominantly of water ice, with trace amounts oftholinimpurities and a peppered coating of approximately 7% amorphouscarbon.[122]The particles that make up the rings range in size from specks of dust up to 10 m.[123]While the othergas giantsalso have ring systems, Saturn's is the largest and most visible.

There is a debate on the age of the rings. One side supports that they are ancient, and werecreated simultaneously with Saturn from the original nebular material(around 4.6 billion years ago),[124]or shortly after theLHB(around 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago).[125][126]The other side supports that they are much younger, created around 100 million years ago.[127]AnMITresearch team, supporting the latter theory, proposed that the rings are remnant of a destroyed moon of Saturn, named″Chrysalis″.[128]

Beyond the main rings, at a distance of 12 million km (7.5 million mi) from the planet is the sparse Phoebe ring. It is tilted at an angle of 27° to the other rings and, likePhoebe,orbits inretrogradefashion.[129]

Some of the moons of Saturn, includingPandoraandPrometheus,act asshepherd moonsto confine the rings and prevent them from spreading out.[130]PanandAtlascause weak, linear density waves in Saturn's rings that have yielded more reliable calculations of their masses.[131]

In September 2023, astronomers reported studies suggesting that the rings of Saturn may have resulted from the collision of two moons "a few hundred million years ago".[132][133]

History of observation and exploration

The observation and exploration of Saturn can be divided into three phases: (1) pre-modern observations with thenaked eye,(2) telescopic observations from Earth beginning in the 17th century, and (3) visitation byspace probes,in orbit or onflyby.In the 21st century, telescopic observations continue from Earth (includingEarth-orbitingobservatorieslike theHubble Space Telescope) and, untilits 2017 retirement,from theCassiniorbiter around Saturn.

Pre-telescopic observation

Saturn has been known since prehistoric times,[134]and in early recorded history it was a major character in various mythologies.Babylonian astronomerssystematically observed and recorded the movements of Saturn.[135]In ancient Greek, the planet was known asΦαίνωνPhainon,[136]and in Roman times it was known as the "star ofSaturn".[137]Inancient Roman mythology,the planet Phainon was sacred to this agricultural god, from which the planet takes its modern name.[138]The Romans considered the god Saturnus the equivalent of theGreek godCronus;in modernGreek,the planet retains the nameCronus—Κρόνος:Kronos.[139]

The Greek scientistPtolemybased his calculations of Saturn's orbit on observations he made while it was inopposition.[140]InHindu astrology,there are nine astrological objects, known asNavagrahas.Saturn is known as "Shani"and judges everyone based on the good and bad deeds performed in life.[138][140]AncientChineseand Japanese culture designated the planet Saturn as the "earth star" (Thổ tinh). This was based onFive Elementswhich were traditionally used to classify natural elements.[141][142][143]

InHebrew,Saturn is calledShabbathai.[144]Its angel isCassiel.Its intelligence or beneficial spirit is'Agȋȇl(Hebrew:אגיאל,romanized:ʿAgyal),[145]and its darker spirit (demon) isZȃzȇl(Hebrew:זאזל,romanized:Zazl).[145][146][147]Zazel has been described as agreat angel,invoked inSolomonic magic,who is "effective inlove conjurations".[148][149]InOttoman Turkish,Urdu,andMalay,the name of Zazel is 'Zuhal', derived from theArabic language(Arabic:زحل,romanized:Zuhal).[146]

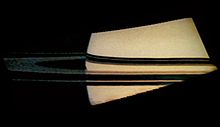

Telescopic pre-spaceflight observations

Saturn's rings require at least a 15-mm-diametertelescope[150]to resolve and thus were not known to exist untilChristiaan Huygenssaw them in 1655 and published about this in 1659.Galileo,with his primitive telescope in 1610,[151][152]incorrectly thought of Saturn's appearing not quite round as two moons on Saturn's sides.[153][154]It was not until Huygens used greater telescopic magnification that this notion was refuted, and the rings were truly seen for the first time. Huygens also discovered Saturn'smoon Titan;Giovanni Domenico Cassinilater discovered four other moons:Iapetus,Rhea,Tethys,andDione.In 1675, Cassini discovered the gap now known as theCassini Division.[155]

No further discoveries of significance were made until 1789 whenWilliam Herscheldiscovered two further moons,MimasandEnceladus.The irregularly shaped satelliteHyperion,which has aresonancewith Titan, was discovered in 1848 by a British team.[156]

In 1899,William Henry Pickeringdiscovered Phoebe, a highlyirregular satellitethat does not rotate synchronously with Saturn as the larger moons do.[156]Phoebe was the first such satellite found and it took more than a year to orbit Saturn in aretrograde orbit.During the early 20th century, research on Titan led to the confirmation in 1944 that it had a thick atmosphere—a feature unique among the Solar System's moons.[157]

Spaceflight missions

Pioneer 11flyby

Pioneer 11made the first flyby of Saturn in September 1979, when it passed within 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of the planet's cloud tops. Images were taken of the planet and a few of its moons, although their resolution was too low to discern surface detail. The spacecraft also studied Saturn's rings, revealing the thin F-ring and the fact that dark gaps in the rings are bright when viewed at a highphase angle(towards the Sun), meaning that they contain fine light-scattering material. In addition,Pioneer 11measured the temperature of Titan.[158]

Voyagerflybys

In November 1980, theVoyager 1probe visited the Saturn system. It sent back the first high-resolution images of the planet, its rings and satellites. Surface features of various moons were seen for the first time.Voyager 1performed a close flyby of Titan, increasing knowledge of the atmosphere of the moon. It proved that Titan's atmosphere is impenetrable atvisible wavelengths;therefore no surface details were seen. The flyby changed the spacecraft's trajectory out of the plane of the Solar System.[159]

Almost a year later, in August 1981,Voyager 2continued the study of the Saturn system. More close-up images of Saturn's moons were acquired, as well as evidence of changes in the atmosphere and the rings. During the flyby, the probe's turnable camera platform stuck for a couple of days and some planned imaging was lost. Saturn's gravity was used to direct the spacecraft's trajectory towards Uranus.[159]

The probes discovered and confirmed several new satellites orbiting near or within the planet's rings, as well as the smallMaxwell Gap(a gap within theC Ring) andKeeler gap(a 42 km-wide gap in theA Ring).[160]

Cassini–Huygensspacecraft

TheCassini–Huygensspace probeentered orbit around Saturn on 1 July 2004. In June 2004, it conducted a close flyby ofPhoebe,sending back high-resolution images and data.Cassini'sflyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, captured radar images of large lakes and their coastlines with numerous islands and mountains. The orbiter completed two Titan flybys before releasing theHuygensprobeon 25 December 2004.Huygensdescended onto the surface of Titan on 14 January 2005.[162]

Starting in early 2005, scientists usedCassinito track lightning on Saturn. The power of the lightning is approximately 1,000 times that of lightning on Earth.[163]

In 2006, NASA reported thatCassinihad found evidence of liquidwater reservoirsno more than tens of meters below the surface that erupt ingeyserson Saturn's moonEnceladus.These jets of icy particles are emitted into orbit around Saturn from vents in the moon's south polar region.[164]Over 100 geysers have been identified on Enceladus.[161]In May 2011, NASA scientists reported that Enceladus "is emerging as the most habitable spot beyond Earth in the Solar System for life as we know it".[165][166]

Cassiniphotographs have revealed a previously undiscovered planetary ring, outside the brighter main rings of Saturn and inside the G and E rings. The source of this ring is hypothesized to be the crashing of a meteoroid offJanusandEpimetheus.[167]In July 2006, images were returned of hydrocarbon lakes near Titan's north pole, the presence of which were confirmed in January 2007. In March 2007, hydrocarbon seas were found near the North pole, the largest of which is almost the size of theCaspian Sea.[168]In October 2006, the probe detected an 8,000 km (5,000 mi) diameter cyclone-like storm with an eyewall at Saturn's south pole.[169]

From 2004 to 2 November 2009, the probe discovered and confirmed eight new satellites.[170]In April 2013,Cassinisent back images of a hurricane at the planet's north pole 20 times larger than those found on Earth, with winds faster than 530 km/h (330 mph).[171]On 15 September 2017, theCassini–Huygensspacecraft performed the "Grand Finale" of its mission: a number of passes through gaps between Saturn and Saturn's inner rings.[172][173]Theatmospheric entryofCassiniended the mission.

Possible future missions

The continued exploration of Saturn is still considered to be a viable option for NASA as part of their ongoingNew Frontiers programof missions. NASA previously requested for plans to be put forward for a mission to Saturn that included theSaturn Atmospheric Entry Probe,and possible investigations into the habitability and possible discovery of life on Saturn's moons Titan and Enceladus byDragonfly.[174][175]

Observation

Saturn is the most distant of the five planets easily visible to the naked eye from Earth, the other four beingMercury,Venus,Mars, and Jupiter. (Uranus, and occasionally4 Vesta,are visible to the naked eye in dark skies.) Saturn appears to the naked eye in the night sky as a bright, yellowish point of light. The meanapparent magnitudeof Saturn is 0.46 with a standard deviation of 0.34.[23]Most of the magnitude variation is due to the inclination of the ring system relative to the Sun and Earth. The brightest magnitude, −0.55, occurs near the time when the plane of the rings is inclined most highly, and the faintest magnitude, 1.17, occurs around the time when they are least inclined.[23]It takes approximately 29.4 years for the planet to complete an entire circuit of theeclipticagainst the background constellations of thezodiac.Most people will require an optical aid (very large binoculars or a small telescope) that magnifies at least 30 times to achieve an image of Saturn's rings in which a clear resolution is present.[48][150]When Earth passes through the ring plane, which occurs twice every Saturnian year (roughly every 15 Earth years), the rings briefly disappear from view because they are so thin. Such a "disappearance" will next occur in 2025, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun for observations.[176]

Saturn and its rings are best seen when the planet is at, or near,opposition,the configuration of a planet when it is at anelongationof 180°, and thus appears opposite the Sun in the sky. A Saturnian opposition occurs every year—approximately every 378 days—and results in the planet appearing at its brightest. Both the Earth and Saturn orbit the Sun on eccentric orbits, which means their distances from the Sun vary over time, and therefore so do their distances from each other, hence varying the brightness of Saturn from one opposition to the next. Saturn also appears brighter when the rings are angled such that they are more visible. For example, during the opposition of 17 December 2002, Saturn appeared at its brightest due to the favorableorientation of its ringsrelative to the Earth,[177]even though Saturn was closer to the Earth and Sun in late 2003.[177]

From time to time, Saturn isoccultedby the Moon (that is, the Moon covers up Saturn in the sky). As with all the planets in the Solar System, occultations of Saturn occur in "seasons". Saturnian occultations will take place monthly for about a 12-month period, followed by about a five-year period in which no such activity is registered. The Moon's orbit is inclined by several degrees relative to Saturn's, so occultations will only occur when Saturn is near one of the points in the sky where the two planes intersect (both the length of Saturn's year and the 18.6-Earth-yearnodal precessionperiod of the Moon's orbit influence the periodicity).[178]

See also

Notes

References

- ^Walter, Elizabeth (21 April 2003).Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary(Second ed.). Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-53106-1.

- ^"Saturnian".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^"Enabling Exploration with Small Radioisotope Power Systems"(PDF).NASA. September 2004. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 22 December 2016.Retrieved26 January2016.

- ^Müller; et al. (2010)."Azimuthal plasma flow in the Kronian magnetosphere".Journal of Geophysical Research.115(A8): A08203.Bibcode:2010JGRA..115.8203M.doi:10.1029/2009ja015122.

- ^"Cronian".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^abcdefghiWilliams, David R. (23 December 2016)."Saturn Fact Sheet".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 17 July 2017.Retrieved12 October2017.

- ^ab"Planetary Physical Parameters".NASAJet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^abcdSimon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets".Astronomy and Astrophysics.282(2): 663–683.Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^Souami, D.; Souchay, J. (July 2012)."The solar system's invariable plane".Astronomy & Astrophysics.543:11.Bibcode:2012A&A...543A.133S.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011.A133.

- ^"HORIZONS Planet-center Batch call for November 2032 Perihelion".ssd.jpl.nasa.gov(Perihelion for Saturn's planet-center (699) occurs on 2032-Nov-29 at 9.0149170au during a rdot flip from negative to positive). NASA/JPL.Archivedfrom the original on 7 September 2021.Retrieved7 September2021.

- ^ab"Solar System Dynamics – Planetary Satellite Discovery Circumstances".NASA. 15 November 2021.Retrieved4 June2022.

- ^ab"Saturn now leads moon race with 62 newly discovered moons".UBC Science.University of British Columbia. 11 May 2023.Retrieved11 May2023.

- ^"By the Numbers – Saturn".NASA Solar System Exploration.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2018.Retrieved5 August2020.

- ^"NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Facts & Figures".Solarsystem.nasa.gov. 22 March 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 2 September 2011.Retrieved8 August2011.

- ^Fortney, J.J.; Helled, R.; Nettlemann, N.; Stevenson, D.J.; Marley, M.S.; Hubbard, W.B.; Iess, L. (6 December 2018)."The Interior of Saturn".In Baines, K.H.; Flasar, F.M.; Krupp, N.; Stallard, T. (eds.).Saturn in the 21st Century.Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–68.ISBN978-1-108-68393-7.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2020.Retrieved23 July2019.

- ^Seligman, Courtney."Rotation Period and Day Length".Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2011.Retrieved13 August2009.

- ^abMcCartney, Gretchen; Wendel, JoAnna (18 January 2019)."Scientists Finally Know What Time It Is on Saturn".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 29 August 2019.Retrieved18 January2019.

- ^abMankovich, Christopher; et al. (17 January 2019)."Cassini Ring Seismology as a Probe of Saturn's Interior. I. Rigid Rotation".The Astrophysical Journal.871(1): 1.arXiv:1805.10286.Bibcode:2019ApJ...871....1M.doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaf798.S2CID67840660.

- ^Hanel, R.A.; et al. (1983). "Albedo, internal heat flux, and energy balance of Saturn".Icarus.53(2): 262–285.Bibcode:1983Icar...53..262H.doi:10.1016/0019-1035(83)90147-1.

- ^Mallama, Anthony; Krobusek, Bruce; Pavlov, Hristo (2017). "Comprehensive wide-band magnitudes and albedos for the planets, with applications to exo-planets and Planet Nine".Icarus.282:19–33.arXiv:1609.05048.Bibcode:2017Icar..282...19M.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023.S2CID119307693.

- ^ab"Saturn's Temperature Ranges".Sciencing.Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2021.Retrieved26 May2021.

- ^"The Planet Saturn".National Weather Service.Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2021.Retrieved26 May2021.

- ^abcdMallama, A.; Hilton, J.L. (2018). "Computing Apparent Planetary Magnitudes for The Astronomical Almanac".Astronomy and Computing.25:10–24.arXiv:1808.01973.Bibcode:2018A&C....25...10M.doi:10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002.S2CID69912809.

- ^"Encyclopedia - the brightest bodies".IMCCE.Retrieved29 May2023.

- ^Knecht, Robin (24 October 2005)."On The Atmospheres Of Different Planets"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 14 October 2017.Retrieved14 October2017.

- ^Brainerd, Jerome James (24 November 2004)."Characteristics of Saturn".The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2011.Retrieved5 July2010.

- ^"General Information About Saturn".Scienceray.28 July 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 7 October 2011.Retrieved17 August2011.

- ^Brainerd, Jerome James (6 October 2004)."Solar System Planets Compared to Earth".The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2011.Retrieved5 July2010.

- ^Dunbar, Brian (29 November 2007)."NASA – Saturn".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2011.Retrieved21 July2011.

- ^Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008)."Mass of Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 26 September 2011.Retrieved17 August2011.

- ^abcRussell, C. T.; et al. (1997)."Saturn: Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere".Science.207(4429): 407–10.Bibcode:1980Sci...207..407S.doi:10.1126/science.207.4429.407.PMID17833549.S2CID41621423.Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2011.Retrieved29 April2007.

- ^"MPEC 2023-J49: S/2006 S 12".Minor Planet Electronic Circulars.Minor Planet Center. 7 May 2023.Retrieved7 May2023.

- ^Munsell, Kirk (6 April 2005)."The Story of Saturn".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; California Institute of Technology. Archived fromthe originalon 16 August 2008.Retrieved7 July2007.

- ^Jones, Alexander (1999).Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus.American Philosophical Society. pp. 62–63.ISBN9780871692337.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2021.Retrieved28 September2021.

- ^Falk, Michael (June 1999),"Astronomical Names for the Days of the Week",Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada,93:122–133,Bibcode:1999JRASC..93..122F,archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2021,retrieved18 November2020

- ^Melosh, H. Jay (2011).Planetary Surface Processes.Cambridge Planetary Science. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 5.ISBN978-0-521-51418-7.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^Gregersen, Erik, ed. (2010).Outer Solar System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and the Dwarf Planets.The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 119.ISBN978-1615300143.Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2020.Retrieved17 February2018.

- ^"Saturn – The Most Beautiful Planet of our solar system".Preserve Articles.23 January 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2012.Retrieved24 July2011.

- ^Williams, David R. (16 November 2004)."Jupiter Fact Sheet".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 26 September 2011.Retrieved2 August2007.

- ^abFortney, Jonathan J.; Nettelmann, Nadine (May 2010). "The Interior Structure, Composition, and Evolution of Giant Planets".Space Science Reviews.152(1–4): 423–447.arXiv:0912.0533.Bibcode:2010SSRv..152..423F.doi:10.1007/s11214-009-9582-x.S2CID49570672.

- ^abcGuillot, Tristan; et al. (2009). "Saturn's Exploration Beyond Cassini-Huygens". In Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.).Saturn from Cassini-Huygens.Springer Science+Business Media B.V. p. 745.arXiv:0912.2020.Bibcode:2009sfch.book..745G.doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_23.ISBN978-1-4020-9216-9.S2CID37928810.

- ^"Saturn - The interior | Britannica".britannica.Retrieved14 April2022.

- ^Fortney, Jonathan J. (2004)."Looking into the Giant Planets".Science.305(5689): 1414–1415.doi:10.1126/science.1101352.PMID15353790.S2CID26353405.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2019.Retrieved28 June2019.

- ^Saumon, D.; Guillot, T. (July 2004). "Shock Compression of Deuterium and the Interiors of Jupiter and Saturn".The Astrophysical Journal.609(2): 1170–1180.arXiv:astro-ph/0403393.Bibcode:2004ApJ...609.1170S.doi:10.1086/421257.S2CID119325899.

- ^"Saturn".BBC. 2000.Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Mankovich, Christopher R.; Fuller, Jim (2021)."A diffuse core in Saturn revealed by ring seismology".Nature Astronomy.5(11): 1103–1109.arXiv:2104.13385.Bibcode:2021NatAs...5.1103M.doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01448-3.S2CID233423431.Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2021.Retrieved22 August2021.

- ^Faure, Gunter; Mensing, Teresa M. (2007).Introduction to planetary science: the geological perspective.Springer. p. 337.ISBN978-1-4020-5233-0.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^abcd"Saturn".National Maritime Museum. 20 August 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 23 June 2008.Retrieved6 July2007.

- ^"Structure of Saturn's Interior".Windows to the Universe. Archived fromthe originalon 17 September 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2010).Planetary Sciences(2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–255.ISBN978-0-521-85371-2.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^"NASA – Saturn".NASA. 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 29 December 2010.Retrieved27 July2007.

- ^Kramer, Miriam (9 October 2013)."Diamond Rain May Fill Skies of Jupiter and Saturn".Space.Archivedfrom the original on 27 August 2017.Retrieved27 August2017.

- ^Kaplan, Sarah (25 August 2017)."It rains solid diamonds on Uranus and Neptune".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on 27 August 2017.Retrieved27 August2017.

- ^"Saturn".Universe Guide.Archivedfrom the original on 23 February 2013.Retrieved29 March2009.[unreliable source?]

- ^Guillot, Tristan (1999). "Interiors of Giant Planets Inside and Outside the Solar System".Science.286(5437): 72–77.Bibcode:1999Sci...286...72G.doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.72.PMID10506563.S2CID6907359.

- ^Courtin, R.; et al. (1967). "The Composition of Saturn's Atmosphere at Temperate Northern Latitudes from Voyager IRIS spectra".Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.15:831.Bibcode:1983BAAS...15..831C.

- ^Cain, Fraser (22 January 2009)."Atmosphere of Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2012.Retrieved20 July2011.

- ^abGuerlet, S.; Fouchet, T.; Bézard, B. (November 2008). Charbonnel, C.; Combes, F.; Samadi, R. (eds.). "Ethane, acetylene and propane distribution in Saturn's stratosphere from Cassini/CIRS limb observations".SF2A-2008: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the French Society of Astronomy and Astrophysics:405.Bibcode:2008sf2a.conf..405G.

- ^Martinez, Carolina (5 September 2005)."Cassini Discovers Saturn's Dynamic Clouds Run Deep".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2011.Retrieved29 April2007.

- ^"Cassini Image Shows Saturn Draped in a String of Pearls"(Press release). Carolina Martinez, NASA. 10 November 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2013.Retrieved3 March2013.

- ^Orton, Glenn S. (September 2009). "Ground-Based Observational Support for Spacecraft Exploration of the Outer Planets".Earth, Moon, and Planets.105(2–4): 143–152.Bibcode:2009EM&P..105..143O.doi:10.1007/s11038-009-9295-x.S2CID121930171.

- ^Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (2009). Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.).Saturn from Cassini-Huygens.Springer. p. 162.Bibcode:2009sfch.book.....D.doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6.ISBN978-1-4020-9216-9.Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^Pérez-Hoyos, S.; Sánchez-Laveg, A.; French, R. G.; J. F., Rojas (2005). "Saturn's cloud structure and temporal evolution from ten years of Hubble Space Telescope images (1994–2003)".Icarus.176(1): 155–174.Bibcode:2005Icar..176..155P.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.01.014.

- ^Kidger, Mark (1992). "The 1990 Great White Spot of Saturn". InMoore, Patrick(ed.).1993 Yearbook of Astronomy.London: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 176–215.Bibcode:1992ybas.conf.....M.

- ^Li, Cheng; de Pater, Imke; Moeckel, Chris; Sault, R. J.; Butler, Bryan; deBoer, David; Zhang, Zhimeng (11 August 2023)."Long-lasting, deep effect of Saturn's giant storms".Science Advances.9(32): eadg9419.Bibcode:2023SciA....9G9419L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.adg9419.PMC10421028.PMID37566653.

- ^Hamilton, Calvin J. (1997)."Voyager Saturn Science Summary".Solarviews. Archived fromthe originalon 26 September 2011.Retrieved5 July2007.

- ^Watanabe, Susan (27 March 2007)."Saturn's Strange Hexagon".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2010.Retrieved6 July2007.

- ^ab"Warm Polar Vortex on Saturn".Merrillville Community Planetarium. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 21 September 2011.Retrieved25 July2007.

- ^Godfrey, D. A. (1988). "A hexagonal feature around Saturn's North Pole".Icarus.76(2): 335.Bibcode:1988Icar...76..335G.doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90075-9.

- ^Sanchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (1993). "Ground-based observations of Saturn's north polar SPOT and hexagon".Science.260(5106): 329–32.Bibcode:1993Sci...260..329S.doi:10.1126/science.260.5106.329.PMID17838249.S2CID45574015.

- ^Overbye, Dennis(6 August 2014)."Storm Chasing on Saturn".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2018.Retrieved6 August2014.

- ^"New images show Saturn's weird hexagon cloud".NBC News. 12 December 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2020.Retrieved29 September2011.

- ^Godfrey, D. A. (9 March 1990). "The Rotation Period of Saturn's Polar Hexagon".Science.247(4947): 1206–1208.Bibcode:1990Sci...247.1206G.doi:10.1126/science.247.4947.1206.PMID17809277.S2CID19965347.

- ^Baines, Kevin H.; et al. (December 2009). "Saturn's north polar cyclone and hexagon at depth revealed by Cassini/VIMS".Planetary and Space Science.57(14–15): 1671–1681.Bibcode:2009P&SS...57.1671B.doi:10.1016/j.pss.2009.06.026.

- ^Ball, Philip (19 May 2006)."Geometric whirlpools revealed".Nature.doi:10.1038/news060515-17.S2CID129016856.Bizarre geometric shapes that appear at the center of swirling vortices in planetary atmospheres might be explained by a simple experiment with a bucket of water but correlating this to Saturn's pattern is by no means certain.

- ^Aguiar, Ana C. Barbosa; et al. (April 2010). "A laboratory model of Saturn's North Polar Hexagon".Icarus.206(2): 755–763.Bibcode:2010Icar..206..755B.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.10.022.Laboratory experiment of spinning disks in a liquid solution forms vortices around a stable hexagonal pattern similar to that of Saturn's.

- ^Sánchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (8 October 2002)."Hubble Space Telescope Observations of the Atmospheric Dynamics in Saturn's South Pole from 1997 to 2002".Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.34:857.Bibcode:2002DPS....34.1307S.Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2010.Retrieved6 July2007.

- ^"NASA catalog page for image PIA09187".NASA Planetary Photojournal.Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011.Retrieved23 May2007.

- ^"Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn".BBC News.10 November 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2012.Retrieved29 September2011.

- ^"NASA Sees into the Eye of a Monster Storm on Saturn".NASA. 9 November 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 7 May 2008.Retrieved20 November2006.

- ^abNemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (13 November 2006)."A Hurricane Over the South Pole of Saturn".Astronomy Picture of the Day.NASA.Retrieved1 May2013.

- ^abMcDermott, Matthew (2000)."Saturn: Atmosphere and Magnetosphere".Thinkquest Internet Challenge.Archivedfrom the original on 20 October 2011.Retrieved15 July2007.

- ^"Voyager – Saturn's Magnetosphere".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 19 March 2012.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Atkinson, Nancy (14 December 2010)."Hot Plasma Explosions Inflate Saturn's Magnetic Field".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2011.Retrieved24 August2011.

- ^Russell, Randy (3 June 2003)."Saturn Magnetosphere Overview".Windows to the Universe. Archived fromthe originalon 6 September 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Cain, Fraser (26 January 2009)."Orbit of Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Michtchenko, T. A.; Ferraz-Mello, S. (February 2001). "Modeling the 5: 2 Mean-Motion Resonance in the Jupiter-Saturn Planetary System".Icarus.149(2): 357–374.Bibcode:2001Icar..149..357M.doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6539.

- ^Jean Meeus,Astronomical Algorithms(Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1998). Average of the nine extremes on p 273. All are within 0.02 AU of the averages.

- ^Kaiser, M. L.; Desch, M. D.; Warwick, J. W.; Pearce, J. B. (1980). "Voyager Detection of Nonthermal Radio Emission from Saturn".Science.209(4462): 1238–40.Bibcode:1980Sci...209.1238K.doi:10.1126/science.209.4462.1238.hdl:2060/19800013712.PMID17811197.S2CID44313317.

- ^Benton, Julius (2006).Saturn and how to observe it.Astronomers' observing guides (11th ed.). Springer Science & Business. p. 136.ISBN978-1-85233-887-9.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^"Scientists Find That Saturn's Rotation Period is a Puzzle".NASA. 28 June 2004.Archivedfrom the original on 29 July 2011.Retrieved22 March2007.

- ^Cain, Fraser (30 June 2008)."Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 25 October 2011.Retrieved17 August2011.

- ^Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, G. (2007)."Saturn's gravitational field, internal rotation and interior structure"(PDF).Science.317(5843): 1384–1387.Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1384A.doi:10.1126/science.1144835.PMID17823351.S2CID19579769.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 April 2020.

- ^"Enceladus Geysers Mask the Length of Saturn's Day"(Press release). NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 22 March 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 7 December 2008.Retrieved22 March2007.

- ^Gurnett, D. A.; et al. (2007)."The Variable Rotation Period of the Inner Region of Saturn's Plasma Disc"(PDF).Science.316(5823): 442–5.Bibcode:2007Sci...316..442G.doi:10.1126/science.1138562.PMID17379775.S2CID46011210.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 February 2020.

- ^Bagenal, F. (2007). "A New Spin on Saturn's Rotation".Science.316(5823): 380–1.doi:10.1126/science.1142329.PMID17446379.S2CID118878929.

- ^Hou, X. Y.; et al. (January 2014)."Saturn Trojans: a dynamical point of view".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.437(2): 1420–1433.Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437.1420H.doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1974.

- ^Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew (August 2021)."Evidence for a Recent Collision in Saturn's Irregular Moon Population".The Planetary Science Journal.2(4): 12.Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2..158A.doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac0979.S2CID236974160.

- ^Tiscareno, Matthew (17 July 2013). "The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring".The Astronomical Journal.135(3): 1083–1091.arXiv:0710.4547.Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1083T.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083.S2CID28620198.

- ^Brunier, Serge (2005).Solar System Voyage.Cambridge University Press. p. 164.ISBN978-0-521-80724-1.

- ^Jones, G. H.; et al. (7 March 2008)."The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea"(PDF).Science.319(5868): 1380–1384.Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J.doi:10.1126/science.1151524.PMID18323452.S2CID206509814.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 March 2018.

- ^Atkinson, Nancy (26 November 2010)."Tenuous Oxygen Atmosphere Found Around Saturn's Moon Rhea".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2012.Retrieved20 July2011.

- ^NASA (30 November 2010)."Thin air: Oxygen atmosphere found on Saturn's moon Rhea".ScienceDaily.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2011.Retrieved23 July2011.

- ^Ryan, Clare (26 November 2010)."Cassini reveals oxygen atmosphere of Saturn′s moon Rhea".UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 16 September 2011.Retrieved23 July2011.

- ^"Saturn's Known Satellites".Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. Archived fromthe originalon 26 September 2011.Retrieved22 June2010.

- ^"Cassini Finds Hydrocarbon Rains May Fill Titan Lakes".ScienceDaily.30 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^"Voyager – Titan".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 26 October 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^"Evidence of hydrocarbon lakes on Titan".NBC News. Associated Press. 25 July 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 2014.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^"Hydrocarbon lake finally confirmed on Titan".Cosmos Magazine.31 July 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 1 November 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^López-Puertas, Manuel (6 June 2013)."PAH's in Titan's Upper Atmosphere".CSIC.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2016.Retrieved6 June2013.

- ^Dyches, Preston; et al. (23 June 2014)."Titan's Building Blocks Might Pre-date Saturn".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 9 September 2018.Retrieved24 June2014.

- ^Battersby, Stephen (26 March 2008)."Saturn's moon Enceladus surprisingly comet-like".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2015.Retrieved16 April2015.

- ^NASA (21 April 2008)."Could There Be Life On Saturn's Moon Enceladus?".ScienceDaily.Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Madrigal, Alexis (24 June 2009)."Hunt for Life on Saturnian Moon Heats Up".Wired Science.Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Spotts, Peter N. (28 September 2005)."Life beyond Earth? Potential solar system sites pop up".USA Today.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2008.Retrieved21 July2011.

- ^Pili, Unofre (9 September 2009)."Enceladus: Saturn′s Moon, Has Liquid Ocean of Water".Scienceray.Archived fromthe originalon 7 October 2011.Retrieved21 July2011.

- ^"Strongest evidence yet indicates Enceladus hiding saltwater ocean".Physorg. 22 June 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Kaufman, Marc (22 June 2011)."Saturn′s moon Enceladus shows evidence of an ocean beneath its surface".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2012.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Greicius, Tony; et al. (22 June 2011)."Cassini Captures Ocean-Like Spray at Saturn Moon".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2011.Retrieved17 September2011.

- ^Chou, Felicia; Dyches, Preston; Weaver, Donna; Villard, Ray (13 April 2017)."NASA Missions Provide New Insights into 'Ocean Worlds' in Our Solar System".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017.Retrieved20 April2017.

- ^Platt, Jane; et al. (14 April 2014)."NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2019.Retrieved14 April2014.

- ^Poulet F.; et al. (2002)."The Composition of Saturn's Rings".Icarus.160(2): 350.Bibcode:2002Icar..160..350P.doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6967.Archivedfrom the original on 29 July 2019.Retrieved28 June2019.

- ^Porco, Carolyn."Questions about Saturn's rings".CICLOPS web site.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2012.Retrieved18 June2017.

- ^Canup, Robin M. (December 2010)."Origin of Saturn's rings and inner moons by mass removal from a lost Titan-sized satellite".Nature.468(7326): 943–946.Bibcode:2010Natur.468..943C.doi:10.1038/nature09661.ISSN1476-4687.PMID21151108.Retrieved22 May2024.

- ^Crida, A.; Charnoz, S. (30 November 2012)."Formation of Regular Satellites from Ancient Massive Rings in the Solar System".Science.338(6111): 1196–1199.arXiv:1301.3808.Bibcode:2012Sci...338.1196C.doi:10.1126/science.1226477.PMID23197530.Retrieved22 May2024.

- ^Charnoz, Sébastien; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Dones, Luke; Salmon, Julien (February 2009)."Did Saturn's rings form during the Late Heavy Bombardment?".Icarus.199(2): 413–428.arXiv:0809.5073.Bibcode:2009Icar..199..413C.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.10.019.Retrieved22 May2024.

- ^Kempf, Sascha; Altobelli, Nicolas; Schmidt, Jürgen; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N.; Estrada, Paul R.; Srama, Ralf (12 May 2023)."Micrometeoroid infall onto Saturn's rings constrains their age to no more than a few hundred million years".Science Advances.9(19): eadf8537.Bibcode:2023SciA....9F8537K.doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf8537.PMC10181170.PMID37172091.

- ^Wisdom, Jack; Dbouk, Rola; Militzer, Burkhard; Hubbard, William B.; Nimmo, Francis; Downey, Brynna G.; French, Richard G. (16 September 2022)."Loss of a satellite could explain Saturn's obliquity and young rings".Science.377(6612): 1285–1289.Bibcode:2022Sci...377.1285W.doi:10.1126/science.abn1234.PMID36107998.S2CID252310492.

- ^Cowen, Rob (7 November 1999)."Largest known planetary ring discovered".Science News.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2011.Retrieved9 April2010.

- ^Russell, Randy (7 June 2004)."Saturn Moons and Rings".Windows to the Universe.Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (3 March 2005)."NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Continues Making New Discoveries".ScienceDaily.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2011.Retrieved19 July2011.

- ^Andrew, Robin George (28 September 2023)."Saturn's Rings May Have Formed in a Surprisingly Recent Crash of 2 Moons - Researchers completed a complex simulation that supports the idea that the giant planet's jewelry emerged hundreds of millions of years ago, not billions".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2023.Retrieved29 September2023.

- ^Teodoro, L.F.A.; et al. (27 September 2023)."A Recent Impact Origin of Saturn's Rings and Mid-sized Moons".The Astrophysical Journal.955(2): 137.arXiv:2309.15156.Bibcode:2023ApJ...955..137T.doi:10.3847/1538-4357/acf4ed.

- ^"Observing Saturn".National Maritime Museum.20 August 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 22 April 2007.Retrieved6 July2007.

- ^Sachs, A. (2 May 1974). "Babylonian Observational Astronomy".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.276(1257): 43–50.Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...43S.doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0008.JSTOR74273.S2CID121539390.

- ^Φαίνων.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;An Intermediate Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^Cicero,De Natura Deorum.

- ^ab"Starry Night Times".Imaginova Corp. 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2009.Retrieved5 July2007.

- ^"Greek Names of the Planets".25 April 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2010.Retrieved14 July2012.

The Greek name of the planet Saturn is Kronos. The Titan Cronus was the father ofZeus,while Saturn was the Roman God of agriculture.

See also theGreek article about the planet. - ^abCorporation, Bonnier (April 1893)."Popular Miscellany – Superstitions about Saturn".The Popular Science Monthly:862.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2016.

- ^De Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1912).Religion in China: universism. a key to the study of Taoism and Confucianism.American lectures on the history of religions. Vol. 10. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 300.Archivedfrom the original on 22 July 2011.Retrieved8 January2010.

- ^Crump, Thomas (1992).The Japanese numbers game: the use and understanding of numbers in modern Japan.Routledge. pp. 39–40.ISBN978-0415056090.

- ^Hulbert, Homer Bezaleel (1909).The passing of Korea.Doubleday, Page & company. p.426.Retrieved8 January2010.

- ^Cessna, Abby (15 November 2009)."When Was Saturn Discovered?".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 14 February 2012.Retrieved21 July2011.

- ^ab"The Magus, Book I: The Celestial Intelligencer: Chapter XXVIII".Sacred-Text.Archivedfrom the original on 19 June 2018.Retrieved4 August2018.

- ^ab"Saturn in Mythology".CrystalLinks.Archivedfrom the original on 8 July 2018.Retrieved5 August2018.

- ^Beyer, Catherine (8 March 2017)."Planetary Spirit Sigils – 01 Spirit of Saturn".ThoughtCo.Archivedfrom the original on 4 August 2018.Retrieved3 August2018.

- ^"Meaning and Origin of: Zazel".FamilyEducation.2014.Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2015.Retrieved3 August2018.

Latin: Angel summoned for love invocations

- ^"Angelic Beings".Hafapea.1998. Archived fromthe originalon 22 July 2018.Retrieved3 August2018.

a Solomonic angel of love rituals

- ^abEastman, Jack (1998)."Saturn in Binoculars".The Denver Astronomical Society. Archived fromthe originalon 28 July 2011.Retrieved3 September2008.

- ^Chan, Gary (2000)."Saturn: History Timeline".Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2011.Retrieved16 July2007.

- ^Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008)."History of Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2012.Retrieved24 July2011.

- ^Cain, Fraser (7 July 2008)."Interesting Facts About Saturn".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2011.Retrieved17 September2011.

- ^Cain, Fraser (27 November 2009)."Who Discovered Saturn?".Universe Today.Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2012.Retrieved17 September2011.

- ^Micek, Catherine."Saturn: History of Discoveries".Archived fromthe originalon 23 July 2011.Retrieved15 July2007.

- ^abBarton, Samuel G. (April 1946). "The names of the satellites".Popular Astronomy.Vol. 54. pp. 122–130.Bibcode:1946PA.....54..122B.

- ^Kuiper, Gerard P.(November 1944). "Titan: a Satellite with an Atmosphere".Astrophysical Journal.100:378–388.Bibcode:1944ApJ...100..378K.doi:10.1086/144679.

- ^"The Pioneer 10 & 11 Spacecraft".Mission Descriptions. Archived fromthe originalon 30 January 2006.Retrieved5 July2007.

- ^ab"Missions to Saturn".The Planetary Society. 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2011.Retrieved24 July2007.

- ^Spence, Pam (1999).The Universe Revealed.Cambridge University Press. p. 64.ISBN978-0-521-64239-2.

- ^abDyches, Preston; et al. (28 July 2014)."Cassini Spacecraft Reveals 101 Geysers and More on Icy Saturn Moon".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 14 July 2017.Retrieved29 July2014.

- ^Lebreton, Jean-Pierre; et al. (December 2005). "An overview of the descent and landing of the Huygens probe on Titan".Nature.438(7069): 758–764.Bibcode:2005Natur.438..758L.doi:10.1038/nature04347.PMID16319826.S2CID4355742.

- ^"Astronomers Find Giant Lightning Storm At Saturn".ScienceDaily LLC. 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2011.Retrieved27 July2007.

- ^Pence, Michael (9 March 2006)."NASA's Cassini Discovers Potential Liquid Water on Enceladus".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2011.Retrieved3 June2011.

- ^Lovett, Richard A. (31 May 2011)."Enceladus named sweetest spot for alien life".Nature:news.2011.337.doi:10.1038/news.2011.337.Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2011.Retrieved3 June2011.

- ^Kazan, Casey (2 June 2011)."Saturn's Enceladus Moves to Top of" Most-Likely-to-Have-Life "List".The Daily Galaxy.Archivedfrom the original on 6 August 2011.Retrieved3 June2011.

- ^Shiga, David (20 September 2007)."Faint new ring discovered around Saturn".NewScientist.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2008.Retrieved8 July2007.

- ^Rincon, Paul (14 March 2007)."Probe reveals seas on Saturn moon".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 11 November 2011.Retrieved26 September2007.

- ^Rincon, Paul (10 November 2006)."Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 2 September 2011.Retrieved12 July2007.

- ^"Mission overview – introduction".Cassini Solstice Mission.NASA / JPL. 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2011.Retrieved23 November2010.

- ^"Massive storm at Saturn's north pole".3 News NZ.30 April 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2014.Retrieved30 April2013.

- ^Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Dyches, Preston (15 September 2017)."NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Ends Its Historic Exploration of Saturn".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2019.Retrieved15 September2017.

- ^Chang, Kenneth (14 September 2017)."Cassini Vanishes Into Saturn, Its Mission Celebrated and Mourned".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 8 July 2018.Retrieved15 September2017.

- ^Foust, Jeff (8 January 2016)."NASA Expands Frontiers of Next New Frontiers Competition".SpaceNews.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2017.Retrieved20 April2017.

- ^April 2017, Nola Taylor Redd 25 (25 April 2017)."'Dragonfly' Drone Could Explore Saturn Moon Titan ".Space.Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2019.Retrieved13 June2020.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Saturn's Rings Edge-On".Classical Astronomy. 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 5 November 2013.Retrieved4 August2013.

- ^abSchmude, Richard W. Jr. (Winter 2003)."Saturn in 2002–03".Georgia Journal of Science.61(4).ISSN0147-9369.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2015.Retrieved29 June2015.

- ^Tanya Hill; et al. (9 May 2014)."Bright Saturn will blink out across Australia – for an hour, anyway".The Conversation.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2014.Retrieved11 May2014.

Further reading

- Alexander, Arthur Francis O'Donel(1980) [1962].The Planet Saturn – A History of Observation, Theory and Discovery.Dover.ISBN978-0-486-23927-9.

- Gore, Rick (July 1981). "Voyager 1 at Saturn: Riddles of the Rings".National Geographic.Vol. 160, no. 1. pp. 3–31.ISSN0027-9358.OCLC643483454.

- Lovett, L.; et al. (2006).Saturn: A New View.Harry N. Abrams.ISBN978-0-8109-3090-2.

- Karttunen, H.; et al. (2007).Fundamental Astronomy(5th ed.). Springer.ISBN978-3-540-34143-7.

- Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; et al. (2007)."Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006".Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy.98(3): 155–180.Bibcode:2007CeMDA..98..155S.doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

- de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2015).Planetary Sciences(2nd updated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 250.ISBN978-0-521-85371-2.

External links

- Saturn overviewby NASA'sScience Mission Directorate

- Saturn fact sheetat theNASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive

- Saturnian System terminologyby the IAU Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature

- Cassini-Huygenslegacy websiteby theJet Propulsion Laboratory

- Interactive 3D gravity simulation of the Cronian systemArchived17 August 2020 at theWayback Machine