Scottish literature

Scottish literatureis literature written inScotlandor byScottish writers.It includes works inEnglish,Scottish Gaelic,Scots,Brythonic,French,Latin,Nornor other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

The earliest extant literature written in what is now Scotland, was composed in Brythonic speech in the sixth century and has survived as part ofWelsh literature.In the following centuries there was literature in Latin, under the influence of the Catholic Church, and inOld English,brought byAngliansettlers. As the state ofAlbadeveloped into the kingdom of Scotland from the eighth century, there was a flourishing literary elite who regularly produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin, sharing a common literary culture with Ireland and elsewhere. After theDavidian Revolutionof the thirteenth century a flourishing French language culture predominated, while Norse literature was produced from areas of Scandinavian settlement. The first surviving major text inEarly Scotsliterature is the fourteenth-century poetJohn Barbour's epicBrus,which was followed by a series of vernacular versions of medieval romances. These were joined in the fifteenth century by Scots prose works.

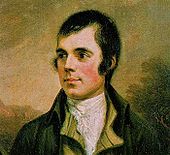

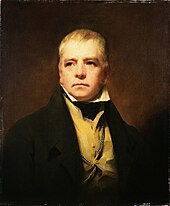

In the early modern era royal patronage supported poetry, prose and drama.James V's court saw works such asSir David Lindsay of the Mount'sThe Thrie Estaitis.In the late sixteenth centuryJames VIbecame patron and member of a circle of Scottish court poets and musicians known as theCastalian Band.When he acceded to the English throne in 1603 many followed him to the new court, but without a centre of royal patronage the tradition of Scots poetry subsided. It was revived after union with England in 1707 by figures includingAllan RamsayandJames Macpherson.The latter'sOssianCycle made him the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation. He helped inspireRobert Burns,considered by many to be the national poet, andWalter Scott,whoseWaverley Novelsdid much to define Scottish identity in the nineteenth century. Towards the end of the Victorian era a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations, includingRobert Louis Stevenson,Arthur Conan Doyle,J. M. BarrieandGeorge MacDonald.

In the twentieth century there was a surge of activity in Scottish literature, known as theScottish Renaissance.The leading figure,Hugh MacDiarmid,attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature. Members of the movement were followed by a new generation of post-war poets includingEdwin Morgan,who would be appointed the firstScots Makarby the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with writers including James Kelman andIrvine Welsh.Scottish poets who emerged in the same period includedCarol Ann Duffy,who was named as the first Scot to be UKPoet Laureatein May 2009.

Middle Ages[edit]

Early Middle Ages[edit]

After the collapse of Roman authority in the early fifth century, four major circles of political and cultural influence emerged in Northern Britain. In the east were thePicts,whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the river Forth to Shetland. In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic)-speaking people ofDál Riata,who had close links with Ireland, from where they brought with them the name Scots. In the south were the British (Brythonic-speaking) descendants of the peoples of the Roman-influenced kingdoms of "The Old North",the most powerful and longest surviving of which was theKingdom of Strathclyde.Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom ofBernicia(later the northern part ofNorthumbria), which reached into what are now the Lothians and the Scotiish Borders in the south-east.[1]To these Christianisation, particularly from the sixth century, addedLatinas an intellectual and written language. Modern scholarship, based on surviving placenames and historical evidence, indicates that thePictsspoke a Brythonic language, but none of their literature seems to have survived into the modern era.[2]However, there is surviving literature from what would become Scotland in Brythonic, Gaelic, Latin andOld English.

Much of the earliestWelsh literaturewas actually composed in or near the country we now call Scotland, in the Brythonic speech, from whichWelshwould be derived, which was not then confined to Wales and Cornwall, although it was only written down in Wales much later. These includeTheGododdin,considered the earliest surviving verse from Scotland, which is attributed to thebardAneirin,said to have been resident in Brythonic kingdom of Gododdin in the sixth century. It is a series ofelegiesto the men of the Gododdin killed fighting at theBattle of Catraetharound 600 AD. Similarly, theBattle of Gwen Ystradis attributed toTaliesin,traditionally thought to be a bard at the court ofRhegedin roughly the same period.[3]

There are religious works inGaelicincluding theElegy forSt Columbaby Dallan Forgaill, c. 597 and "In Praise of St Columba" by Beccan mac Luigdech of Rum, c. 677.[4]InLatinthey include a "Prayer for Protection" (attributed to St Mugint), c. mid-sixth century andAltus Prosator( "The High Creator", attributed to St Columba), c. 597.[5]What is arguably the most important medieval work written in Scotland, theVita Columbae,byAdomnán,abbot of Iona (627/8–704), was also written in Latin.[6]The next most important piece of Scottish hagiography, the verseLife of St. Ninian,was written in Latin inWhithornin the eighth century.[7]

In Old English there isTheDream of the Rood,from which lines are found on theRuthwell Cross,making it the only surviving fragment ofNorthumbrianOld English from early Medieval Scotland.[8]It has also been suggested on the basis of ornithological references that the poemThe Seafarerwas composed somewhere near theBass Rockin East Lothian.[9]

High Middle Ages[edit]

Beginning in the later eighth century,Vikingraids and invasions may have forced a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns that culminated in the rise ofCínaed mac Ailpín(Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s, which brought to power theHouse of Alpinand the creation of theKingdom of Alba.[10]Historical sources, as well as place name evidence, indicate the ways in which the Pictish language in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, Old English and laterNorse.[11]The Kingdom of Alba was overwhelmingly an oral society dominated by Gaelic culture. Our fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there would have beenfilidh,who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge and culture in Gaelic to the next generation.[12][13]

From the eleventh century French,Flemishand particularly English became the main languages of Scottishburghs,most of which were located in the south and east.[14]At least from the accession ofDavid I(r. 1124–53), as part of aDavidian Revolutionthat introduced French culture and political systems, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French. After this "gallicisation"of the Scottish court, a less highly regarded order of bards took over the functions of the filidh and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century. They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by theMacMhuirichdynasty, who were bards to theLord of the Isles,[15]existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century.[13]Members of bardic schools were trained in the complex rules and forms of Gaelic poetry.[16]Much of their work was never written down and what survives was only recorded from the sixteenth century.[12]

It is possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in medieval Scotland than is often thought, but has not survived because the Gaelic literary establishment of eastern Scotland died out before the fourteenth century. Thomas Owen Clancy has argued that theLebor Bretnach,the so-called "Irish Nennius", was written in Scotland, and probably at the monastery in Abernethy, but this text survives only from manuscripts preserved in Ireland.[17]Other literary work that has survived includes that of the prolific poetGille Brighde Albanach.About 1218, Gille Brighde wrote a poem—Heading for Damietta—on his experiences of theFifth Crusade.[18]

In the thirteenth century,Frenchflourished as aliterary language,and produced theRoman de Fergus,the earliest piece of non-Celticvernacularliterature to survive from Scotland.[19]Many other stories in theArthurian Cycle,written in French and preserved only outside Scotland, are thought by some scholars including D. D. R. Owen, to have been written in Scotland. There is some Norse literature from areas of Scandinavian settlement, such as theNorthern Islesand theWestern Isles.The famousOrkneyinga Sagahowever, although it pertains to theEarldom of Orkney,was written inIceland.[20]In addition to French, Latin too was a literary language, with works that include the "Carmen de morte Sumerledi", a poem which exults triumphantly the victory of the citizens of Glasgow overSomairle mac Gilla Brigte[21]and the "Inchcolm Antiphoner", a hymn in praise of St. Columba.[22]

Late Middle Ages[edit]

In the late Middle Ages,early Scots,often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.[16]It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of theRiver Tay,began a steady decline.[16]Lowland writers began to treat Gaelic as a second class, rustic and even amusing language, helping to frame attitudes towards the highlands and to create a cultural gulf with the lowlands.[16]

The first surviving major text in Scots literature isJohn Barbour'sBrus(1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion until the end of the war of independence.[23]The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporaryChaucerin England.[24]In the early fifteenth century these were followed byAndrew of Wyntoun's verseOrygynale Cronykil of ScotlandandBlind Harry'sThe Wallace,which blendedhistorical romancewith theverse chronicle.They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, includingThe Buik of Alexander,Launcelot o the LaikandThe Porteous of NoblenesbyGilbert Hay.[16]

Much Middle Scots literature was produced bymakars,poets with links to the royal court, which includedJames I(who wroteThe Kingis Quair). Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with theKirk.However, Dunbar'sLament for the Makaris(c.1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost.[25]Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such asRobert Henryson,William Dunbar,Walter KennedyandGavin Douglashave been seen as leading a golden age inScottish poetry.[16]

In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as theAuchinleck Chronicle,[26]the first complete surviving work includesJohn Ireland'sThe Meroure of Wyssdome(1490).[27]There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, includingThe Book of the Law of Armysand theOrder of Knychthodeand the treatiseSecreta Secretorum,an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice toAlexander the Great.[16]The establishment of a printing press under royal patent in 1507 would begin to make it easier to disseminate Scottish literature and was probably aimed at bolstering Scottish national identity.[28]The first Scottish press was established inSouthgaitin Edinburgh by the merchantWalter Chepman(c. 1473–c. 1528) and the booksellerAndrew Myllar(f. 1505–08). Although the first press was relatively short lived, beside law codes and religious works, the press also produced editions of the work of Scottish makars before its demise, probably about 1510. The next recorded press was that ofThomas Davidson(f. 1532–42), the first in a long line of "king's printers", who also produced editions of works of the makars.[29]The landmark work in the reign ofJames IVwas Gavin Douglas's version ofVirgil'sAeneid,theEneados,which was the first complete translation of a majorclassicaltext in theScots languageand the first successful example of its kind in anyAnglic language.It was finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster atFlodden.[16]

Early modern era[edit]

| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

Sixteenth century[edit]

As a patron of poets and authorsJames V(r. 1513–42) supported William Stewart andJohn Bellenden,who translated the LatinHistory of Scotlandcompiled in 1527 byHector Boece,into verse and prose.[30]David Lyndsay(c. 1486–1555), diplomat and the head of theLyon Court,was a prolific poet. He wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires.[31]George Buchanan(1506–82) had a major influence as a Latin poet, founding a tradition of neo-Latin poetry that would continue in to the seventeenth century.[32]Contributors to this tradition included royal secretaryJohn Maitland(1537–95), reformerAndrew Melville(1545–1622),John Johnston(1570?–1611) andDavid Hume of Godscroft(1558–1629).[33]

From the 1550s, in the reign ofMary, Queen of Scots(r. 1542–67) and the minority of her sonJames VI(r. 1567–1625), cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and by political turmoil. The Kirk, heavily influenced byCalvinism,also discouraged poetry that was not devotional in nature. Nevertheless, poets from this period includedRichard Maitlandof Lethington (1496–1586), who produced meditative and satirical verses in the style of Dunbar;John Rolland(fl. 1530–75), who wrote allegorical satires in the tradition of Douglas and courtier and ministerAlexander Hume(c. 1556–1609), whose corpus of work includes nature poetry andepistolary verse.Alexander Scott's (?1520–82/3) use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI's adult reign.[31]

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI strongly promoted the literature of the country of his birth in Scots. His treatise,Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody,published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, to which he applied Renaissance principles.[34]He became patron and member of a loose circle of ScottishJacobeancourt poets and musicians, later called theCastalian Band,which includedWilliam Fowler(c. 1560–1612),John Stewart of Baldynneis(c. 1545–c. 1605), andAlexander Montgomerie(c. 1550–98).[35]They translated key Renaissance texts and produced poems using French forms, includingsonnetsand short sonnets, for narrative, nature description, satire and meditations on love. Later poets that followed in this vein includedWilliam Alexander(c. 1567–1640), Alexander Craig (c. 1567–1627) andRobert Ayton(1570–1627).[31]By the late 1590s the king's championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne.[36]

Lyndsay produced an interlude atLinlithgow Palacefor the king and queen thought to be a version of his playThe Thrie Estaitisin 1540, which satirised the corruption of church and state, and which is the only complete play to survive from before the Reformation.[30]Buchanan was major influence on Continental theatre with plays such asJephethsandBaptistes,which influencedPierre CorneilleandJean Racineand through them the neo-classical tradition in French drama, but his impact in Scotland was limited by his choice of Latin as a medium.[37]The anonymousThe Maner of the Cyring of ane Play(before 1568)[38]andPhilotus(published in London in 1603), are isolated examples of surviving plays. The latter is a vernacular Scots comedy of errors, probably designed for court performance for Mary, Queen of Scots or James VI.[39]The same system of professional companies of players and theatres that developed in England in this period was absent in Scotland, but James VI signalled his interest in drama by arranging for a company of English players to erect a playhouse and perform in 1599.[40]

Seventeenth century[edit]

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", following his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the EnglishAuthorised King James Versionof the Bible. In 1617 interpreters were declared no longer necessary in the port of London because Scots and Englishmen were now "not so far different bot ane understandeth ane uther". Jenny Wormald, describes James as creating a "three-tier system, with Gaelic at the bottom and English at the top".[41]The loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. A number of Scottish poets, including William Alexander, John Murray and Robert Aytoun accompanied the king to London, where they continued to write,[42]but they soon began toanglicisetheir written language.[43]James's characteristic role as active literary participant and patron in the English court made him a defining figure for English Renaissance poetry and drama, which would reach a pinnacle of achievement in his reign,[44]but his patronage for thehigh stylein his own Scottish tradition largely became sidelined.[45]The only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure wasWilliam Drummond of Hawthornden(1585–1649).[38]

As the tradition of classical Gaelic poetry declined, a new tradition of vernacular Gaelic poetry began to emerge. While Classical poetry used a language largely fixed in the twelfth century, the vernacular continued to develop. In contrast to the Classical tradition, which usedsyllabic metre,vernacular poets tended to usestressed metre.However, they shared with the Classic poets a set of complex metaphors and role, as the verse was still often panegyric. A number of these vernacular poets were women,[46]such as Mary MacLeod of Harris (c. 1615–1707).[47]

The tradition of neo-Latin poetry reached its fruition with the publication of the anthology of theDeliciae Poetarum Scotorum(1637), published in Amsterdam byArthur Johnston(c. 1579–1641) andSir John Scott of Scotstarvet(1585–1670) and containing work by the major Scottish practitioners since Buchanan.[32]This period was marked by the work of the first named female Scottish poets.[38]Elizabeth Melville's (f. 1585–1630)Ane Godlie Dream(1603) was a popular religious allegory and the first book published by a woman in Scotland.[48]Anna Hume,daughter of David Hume of Godscroft, adaptedPetrarch'sTriumphsasTriumphs of Love: Chastitie: Death(1644).[38]

This was the period when theballademerged as a significant written form in Scotland. Some ballads may date back to the late medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including "Sir Patrick Spens"and"Thomas the Rhymer",but which are not known to have existed until the eighteenth century.[49]They were probably composed and transmitted orally and only began to be written down and printed, often asbroadsidesand as part ofchapbooks,later being recorded and noted in books by collectors includingRobert BurnsandWalter Scott.[50]From the seventeenth century they were used as a literary form by aristocratic authors includingRobert Sempill(c. 1595–c. 1665),Lady Elizabeth Wardlaw(1627–1727) andLady Grizel Baillie(1645–1746).[51]

The loss of a royal court also meant there was no force to counter the kirk's dislike of theatre, which struggled to survive in Scotland.[42]However, it was not entirely extinguished. The kirk used theatre for its own purposes in schools and was slow to suppress popularfolk dramas.[37]Surviving plays for the period include William Alexander'sMonarchicke Tragedies,written just before his departure with the king for England in 1603. They werecloset dramas,designed to be read rather than performed, and already indicate Alexander's preference for southern English over the Scots language.[39]There were some attempts to revive Scottish drama. In 1663 Edinburgh lawyer William Clerke wroteMarciano or the Discovery,a play about the restoration of a legitimate dynasty in Florence after many years of civil war. It was performed at the Tennis-Court Theatre atHolyrood Palacebefore the parliamentary high commissionerJohn Leslie, Earl of Rothes.[52]Thomas Sydsurf'sTarugo's Wiles or the Coffee House,was first performed in London in 1667 and then in Edinburgh the year after and drew onSpanish comedy.[53]A relative of Sydsurf, physicianArchibald Pitcairne(1652–1713) wroteThe Assembly or Scotch Reformation(1692), a ribald satire on the morals of the Presbyterian kirk, circulating in manuscript, but not published until 1722, helping to secure the association betweenJacobitismand professional drama that discouraged the creation of professional theatre.[54]

Eighteenth century[edit]

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education.[55]Nevertheless, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots.[56]Literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation.Allan Ramsay(1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishingThe Ever Green(1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period.[57]He led the trend forpastoralpoetry, helping to develop theHabbie stanza,which would be later be used by Robert Burns as apoetic form.[58]HisTea-Table Miscellany(1724–37) contained poems old Scots folk material, his own poems in the folk style and "gentilizings" of Scots poems in the English neo-classical style.[59]His pastoral operaThe Gentle Shepherdwas one of the most influential works of the era.[54]He would also play a leading role in supporting drama in Scotland and the attempt to found a permanent theatre in the capital.[60]

Ramsay was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English. These includedWilliam Hamilton of Gilbertfield(c. 1665–1751), Robert Crawford (1695–1733),Alexander Ross(1699–1784), the JacobiteWilliam Hamiltonof Bangour (1704–54), socialiteAlison RutherfordCockburn (1712–94), and poet and playwrightJames Thomson's (1700–48), most famous for the nature poetry of hisSeasons.[61]Tobias Smollett(1721–71) was a poet, essayist, satirist and playwright, but is best known for hispicaresque novels,such asThe Adventures of Roderick Random(1748) andThe Adventures of Peregrine Pickle(1751) for which he is often seen as Scotland's first novelist.[62]His work would be a major influence on later novelists such asThackerayandDickens.[63]

The early eighteenth century was also a period of innovation in Gaelic vernacular poetry. Major figures includedRob DonnMackay (1714–78) andDonnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir(Duncan Ban MacIntyre) (1724–1812). The most significant figure in the tradition wasAlasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair(Alasdair MacDonald) (c. 1698–1770). His interest in traditional forms can be seen in his most significant poemClanranald's Gallery.He also mixed these traditions with influences from the Lowlands, including Thompson'sSeasons,which helped inspire a new form of nature poetry in Gaelic, which was not focused on their relations to human concerns.[47]

James Macphersonwas the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written byOssian,he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of theClassicalepics.Fingalwritten in 1762 was speedily translated into many European languages, and its deep appreciation of natural beauty and the melancholy tenderness of its treatment of the ancient legend did more than any single work to bring about theRomantic movementin European, and especially in German, literature, influencingHerderandGoethe.[64]Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from the Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.[65]

Robert Burns was highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as thenational poetof Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collectedfolk songsfrom across Scotland, often revising oradaptingthem. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne"is often sung atHogmanay(the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae"served for a long time as an unofficialnational anthemof the country.[66]Burns's poetry drew upon a substantial familiarity with and knowledge ofClassical,Biblical,andEnglish literature,as well as the Scottish Makar tradition.[67]Burns was skilled in writing not only in theScots languagebut also in theScottish Englishdialectof the English language. Some of his works, such as "Love and Liberty" (also known as "The Jolly Beggars" ), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.[68]His themes includedrepublicanism,Radicalism,Scottish patriotism,anticlericalism,class inequalities,gender roles,commentary on theScottish Kirkof his time,Scottish cultural identity,poverty,sexuality,and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising.[69]Other major literary figures connected with Romanticism include the poets and novelistsJames Hogg(1770–1835),Allan Cunningham(1784–1842) andJohn Galt(1779–1839),[70]

Drama was pursued by Scottish playwrights in London such asCatherine Trotter(1679–1749), born in London to Scottish parents and later moving to Aberdeen. Her plays and included the verse-tragedyFatal Friendship(1698), the comedyLove at a Loss(1700) and the historyThe Revolution in Sweden(1706). David Crawford's (1665–1726) plays included theRestoration comediesCourtship A-la-Mode(1700) andLove at First Sight(1704). These developed the character of the stage Scot, often a clown, but cunning and loyal.Newburgh Hamilton(1691–1761), born in Ireland of Scottish descent, produced the comediesThe Petticoat-Ploter(1712) andThe Doating LoversorThe Libertine(1715). He later wrote the libretto for Handel'sSamson(1743), closely based onJohn Milton'sSamson Agonistes.James Thomson's plays often dealt with the contest between public duty and private feelings, includedSophonisba(1730),Agamemnon(1738) andTancrid and Sigismuda(1745), the last of which was an international success.David Mallet's (c. 1705–65)Eurydice(1731) was accused of being a coded Jacobite play and his later work indicates opposition to theWalpoleadministration. The operaMasque of Alfred(1740) was a collaboration between Thompson, Mallet and composerThomas Arne,with Thompson supplying the lyrics for his most famous work, the patriotic song "Rule, Britannia!".[71]

In Scotland performances were largely limited to performances by visiting actors, who faced hostility from the Kirk.[54]The Edinburgh Company of Players were able to perform in Dundee, Montrose, Aberdeen and regular performances at the Taylor's Hall in Edinburgh under the protection of a Royal Patent.[54]Ramsay was instrumental in establishing them in a small theatre in Carruber's Close in Edinburgh,[72]but the passing of the1737 Licensing Actmade their activities illegal and the theatre soon closed.[60]A new theatre was opened at Cannongate in 1747 and operated without a licence into the 1760s.[72]In the later eighteenth century, many plays were written for and performed by small amateur companies and were not published and so most have been lost. Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas",primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Hogg, Galt andJoanna Baillie(1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition andGothicRomanticism.[73]

Nineteenth century[edit]

Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century,[74]with a descent of into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popularWhistle Binkieanthologies (1830–90).[75]However, Scotland continued to produce talented and successful poets, including weaver-poetWilliam Thom(1799–1848), Lady Margaret Maclean Clephane Compton Northampton (d. 1830),William Edmondstoune Aytoun(1813–65) andThomas Campbell(1777–1844), whose works were extensively reprinted in the period 1800–60.[74]Among the most influential poets of the later nineteenth century wereJames Thomson(1834–82) andJohn Davidson(1857–1909), whose work would have a major impact on modernist poets including Hugh MacDiarmid,Wallace StevensandT. S. Eliot.[76]TheHighland Clearancesand widespread emigration significantly weakened Gaelic language and culture and had a profound impact on the nature of Gaelic poetry. The best poetry in this vein contained a strong element of protest, including Uilleam Mac Dhun Lèibhe's (William Livingstone, 1808–70) protest against theIslayand Seonaidh Phàdraig Iarsiadair's (John Smith, 1848–81) condemnation of those responsible for the clearances. The best known Gaelic poet of the era was Màiri Mhòr nan Óran (Mary MacPherson, 1821–98), whose evocation of place and mood has made her among the most enduring Gaelic poets.[47]

Walter Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work,Waverleyin 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[77]It launched a highly successful career, with other historical novels such asRob Roy(1817),The Heart of Midlothian(1818) andIvanhoe(1820). Scott probably did more than any other figure to define and popularise Scottish cultural identity in the nineteenth century.[78]

Scottish "national drama" emerged in the early 1800s, as plays with specifically Scottish themes began to dominate the Scottish stage. The existing repertoire of Scottish-themed plays includedJohn Home'sDouglas(1756) and Ramsay'sThe Gentle Shepherd(1725), with the last two being the most popular plays among amateur groups.[79]Scott was keenly interested in drama, becoming a shareholder in theTheatre Royal,Edinburgh.[80]Baillie's Highland themedThe Family Legendwas first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama.[81]Scott also wrote five plays, of whichHallidon Hill(1822) andMacDuff's Cross(1822), were patriotic Scottish histories.[80]Adaptations of the Waverley novels, largely first performed in minor theatres, rather than the largerPatent theatres,includedThe Lady in the Lake(1817),The Heart of Midlothian(1819), andRob Roy,which underwent over 1,000 performances in Scotland in this period. Also adapted for the stage wereGuy Mannering,The Bride of LammermoorandThe Abbot.These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.[79]

Scotland was also the location of two of the most important literary magazines of the era,The Edinburgh Review,founded in 1802 andBlackwood's Magazine,founded in 1817. Together they had a major impact on the development of British literature and drama in the era of Romanticism.[82][83]

Thomas Carlyle,in such works asSartor Resartus(1833–34),The French Revolution: A History(1837) andOn Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History(1841), profoundly influenced philosophy and literature of the age.

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations.Robert Louis Stevenson's work included theurban GothicnovellaStrange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde(1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books likeKidnappedandTreasure Island.Arthur Conan Doyle'sSherlock Holmesstories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. The "kailyard tradition"at the end of the century, brought elements offantasyandfolkloreback into fashion as can be seen in the work of figures likeJ. M. Barrie,most famous for his creation ofPeter PanandGeorge MacDonaldwhose works includingPhantastesplayed a major part in the creation of the fantasy genre.[84]

Twentieth century to the present[edit]

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced bymodernismand resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance.[85]The leading figure in the movement wasHugh MacDiarmid(the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle"(1936), developing a form ofSynthetic Scotsthat combined different regional dialects and archaic terms.[85]Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poetsEdwin MuirandWilliam Soutar,the novelistsNeil Gunn,George Blake,Nan Shepherd,A. J. Cronin,Naomi Mitchison,Eric LinklaterandLewis Grassic Gibbon,and the playwrightJames Bridie.All were born within a fifteen-year period (1887–1901) and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues.[85]This period saw the emergence of a tradition of popular or working class theatre. Hundreds of amateur groups were established, particularly in the growing urban centres of the Lowlands. Amateur companies encouraged native playwrights, includingRobert McLellan.[86]

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, includingRobert GariochandSydney Goodsir Smith.Others demonstrated a greater interest in English language poetry, among themNorman MacCaig,George Bruce andMaurice Lindsay.[85]George Mackay Brownfrom Orkney, andIain Crichton Smithfrom Lewis, wrote both poetry and prose fiction shaped by their distinctive island backgrounds.[85]The Glaswegian poetEdwin Morganbecame known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the firstScots Makar(the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004.[87]The shift to drama that focused on working class life in the post-war period gained momentum with Robert McLeish'sThe Gorbals Story[88]and the work ofEna Lamont Stewart,[89]Robert Kempand George Munro.[88]Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such asMuriel Spark,James Kennaway,Alexander Trocchi,Jessie KessonandRobin Jenkinsspent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes, as in Spark's Edinburgh-setThe Prime of Miss Jean Brodie(1961)[85]and Kennaway's script for the filmTunes of Glory(1956).[90]Successful mass-market works included the action novels ofAlistair MacLean,and the historical fiction ofDorothy Dunnett.[85]A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s includedShena Mackay,Alan Spence,Allan Massieand the work ofWilliam McIlvanney.[85]

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacherPhilip Hobsbaum.Also important in the movement wasPeter Kravitz,editor ofPolygon Books.Members of the group that would come to prominence as writers includedJames Kelman,Alasdair Gray,Liz Lochhead,Tom LeonardandAonghas MacNeacail.[85]In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement includedIrvine Welsh'sTrainspotting(1993), Warner'sMorvern Callar(1995), Gray'sPoor Things(1992) and Kelman'sHow Late It Was, How Late(1994).[85]These works were linked by a sometimes overtly political reaction toThatcherismthat explored marginal areas of experience and used vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots). Gray andIain Banksled a wave of fantasy, speculative and science-fiction writing with notable authors includingKen MacLeod,Andrew Crumey,Michel Faber,Alice ThompsonandFrank Kuppner.Scottish crime fiction has been a major area of growth with the success of novelists includingVal McDermid,Frederic Lindsay,Christopher Brookmyre,Quintin Jardine,Denise Minaand particularly the success of Edinburgh'sIan Rankinand hisInspector Rebusnovels.[85]Scottish play writing became increasingly internationalised, with Scottish writers such as Liz Lochhead and Edwin Morgan adapting classic texts, whileJo CliffordandDavid Greiginvestigated European themes.[91]This period also saw the emergence of a new generation of Scottish poets that became leading figures on the UK stage, includingDon Paterson,Kathleen Jamie,Douglas Dunn,Robert Crawford,andCarol Ann Duffy.[85]Glasgow-born Duffy was named asPoet Laureatein May 2009, the first woman, the first Scot and the first openly gay poet to take the post.[92]

See also[edit]

- Association for Scottish Literary Studies

- International Association for the Study of Scottish Literatures

- Books in the "Famous Scots Series"

- Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry

- History of the Scots language

- Literature in the other languages of Britain

- Modern Scottish Poetry (Faber)

- English literature

- G. Ross Royfounding editor of the journalStudies in Scottish Literature

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^J. R. Maddicott and D. M. Palliser, eds,The Medieval State: essays presented to James Campbell(London: Continuum, 2000),ISBN1-85285-195-3,p. 48.

- ^J. T. Koch,Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia(ABC-CLIO, 2006),ISBN1-85109-440-7,p. 305.

- ^R. T. Lambdin and L. C. Lambdin,Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature(London: Greenwood, 2000),ISBN0-313-30054-2,p. 508.

- ^J. T. Koch,Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia(ABC-CLIO, 2006),ISBN1-85109-440-7,p. 999.

- ^I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0-7486-1615-2,p. 94.

- ^C. Gross,The Sources and Literature of English History from the Earliest Times to about 1485(Elibron Classics Series, 1999),ISBN0-543-96628-3,p. 217.

- ^T. O. Clancy, "Scottish literature before Scottish literature", in G. Carruthers and L. McIlvanney, eds,The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature(Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2012),ISBN0521189365,p. 19.

- ^E. M. Treharne,Old and Middle English c.890-c.1400: an Anthology(Wiley-Blackwell, 2004),ISBN1-4051-1313-8,p. 108.

- ^T. O. Clancy, "Scottish literature before Scottish literature", in G. Carruthers and L. McIlvanney, eds,The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature(Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2012),ISBN0521189365,p. 16.

- ^B. Yorke,The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800(Pearson Education, 2006),ISBN0582772923,p. 54.

- ^W. O. Frazer and A. Tyrrell,Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain(London: Continuum, 2000),ISBN0718500849,p. 238.

- ^abR. Crawford,Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),ISBN019538623X.

- ^abR. A. Houston,Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002),ISBN0521890888,p. 76.

- ^K. J. Stringer, "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in E. J. Cowan and R. A. McDonald, eds,Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages(East Lothian: Tuckwell Press, 2000),ISBN1862321515,p. 133.

- ^K. M. Brown,Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from the Reformation to the Revolutions(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004),ISBN0748612998,p. 220.

- ^abcdefghJ. Wormald,Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991),ISBN0748602763,pp. 60–7.

- ^T. O. Clancy, "Scotland, the 'Nennian' recension of the Historia Brittonum, and the Lebor Bretnach", in S. Taylor, ed.,Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297(Dublin/Portland, 2000),ISBN1-85182-516-9,pp. 87–107.

- ^T. O. Clancy and G. Márkus,The Triumph Tree: Scotland's Earliest Poetry, 550–1350(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1998),ISBN0-86241-787-2,pp. 247–283.

- ^M. Fry,Edinburgh(London: Pan Macmillan, 2011),ISBN0-330-53997-3.

- ^T. O. Clancy and G. Márkus,The Triumph Tree: Scotland's Earliest Poetry, 550–1350(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1998),ISBN0-86241-787-2,pp. 7–8.

- ^I. F. Grant,The Lordship of the Isles: Wanderings in the Lost Lordship(Mercat, 1982),ISBN0-901824-68-2,p. 495.

- ^I. Bradley,Columba: Pilgrim and Penitent, 597–1997(Wild Goose, 1996),ISBN0-947988-81-5,p. 97.

- ^A. A. M. Duncan, ed.,The Brus(Canongate, 1997),ISBN0-86241-681-7,p. 3.

- ^N. Jayapalan,History of English Literature(Atlantic, 2001),ISBN81-269-0041-5,p. 23.

- ^A. Grant,Independence and Nationhood, Scotland 1306–1469(Baltimore: Edward Arnold, 1984), pp. 102–3.

- ^Thomas Thomson,ed.,Auchinleck Chronicle(Edinburgh, 1819).

- ^J. Martin,Kingship and Love in Scottish poetry, 1424–1540(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008),ISBN0-7546-6273-X,p. 111.

- ^P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams,A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry(Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006),ISBN1-84384-096-0,pp. 26–9.

- ^A. MacQuarrie, "Printing and publishing", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7,pp. 491–3.

- ^abI. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0-7486-1615-2,pp. 256–7.

- ^abcT. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7,pp. 129–30.

- ^abR. Mason, "Culture: 4 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): general", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7,pp. 120–3.

- ^"Bridging the Continental divide: neo-Latin and its cultural role in Jacobean Scotland, as seen in theDelitiae Poetarum Scotorum(1637) ",University of Glasgow. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9,pp. 126–7.

- ^R. D. S. Jack,Alexander Montgomerie(Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1985),ISBN0-7073-0367-2,pp. 1–2.

- ^R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9,p. 137.

- ^abI. Brown, "Introduction: a lively tradition and collective amnesia", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076,pp. 1–3.

- ^abcdT. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 7 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): literature", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7,pp. 127–8.

- ^abS. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076,p. 15.

- ^S. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076,p. 21.

- ^J. Wormald,Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991),ISBN0748602763,pp. 192–3.

- ^abK. M. Brown, "Scottish identity", in B. Bradshaw and P. Roberts, eds,British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003),ISBN0521893615,pp. 253–3.

- ^M. Spiller, "Poetry after the Union 1603–1660" in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9,pp. 141–52.

- ^N. Rhodes, "Wrapped in the Strong Arm of the Union: Shakespeare and King James" in W. Maley and A. Murphy, eds,Shakespeare and Scotland(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004),ISBN0-7190-6636-0,pp. 38–9.

- ^R. D. S. Jack, "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9,pp. 137–8.

- ^K. Chedgzoy,Women's Writing in the British Atlantic World(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012),ISBN113946714X,p. 105.

- ^abcJ. MacDonald, "Gaelic literature" in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7,pp. 255–7.

- ^I. Mortimer,The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England(Random House, 2012),ISBN1847921140,p. 70.

- ^E. Lyle,Scottish Ballads(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2001),ISBN0-86241-477-6,pp. 9–10.

- ^R. Crawford,Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),ISBN0-19-538623-X,pp. 216–9.

- ^R. Crawford,Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),ISBN0-19-538623-X,pp. 224, 248 and 257.

- ^C. Jackson,Restoration Scotland, 1660–1690: Royalist Politics, Religion and Ideas(Boydell Press, 2003),ISBN0851159303,p. 17.

- ^T. Tobin, ed.,The Assembly(Purdue University Press, 1972),ISBN091119830X,p. 5.

- ^abcdI. Brown, "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076,pp. 28–30.

- ^C. Jones,A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century(Edinburgh: John Donald, 1993), p. vii.

- ^J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds,The Edinburgh Companion to Scots(Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003),ISBN0-7486-1596-2,p. 14.

- ^R. M. Hogg,The Cambridge History of the English Language(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994),ISBN0521264782,p. 39.

- ^J. Buchan (2003),Crowded with Genius,Harper Collins, p.311,ISBN0-06-055888-1

- ^"Poetry in Scots: Brus to Burns" in C. R. Woodring and J. S. Shapiro, eds,The Columbia History of British Poetry(Columbia University Press, 1994),ISBN0585041555,p. 100.

- ^abB. Bell, "The national drama, Joanna Baille and the national theatre", in I. Brown,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire, 1707–1918(Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813,p. 288.

- ^C. Maclachlan,Before Burns(Canongate Books, 2010),ISBN1847674666,pp. ix–xviii.

- ^J. C. Beasley,Tobias Smollett: Novelist(University of Georgia Press, 1998),ISBN0820319716,p. 1.

- ^R. Crawford,Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),ISBN0-19-538623-X,p. 313.

- ^J. Buchan (2003),Crowded with Genius,Harper Collins, p.163,ISBN0-06-055888-1

- ^D. Thomson (1952),The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian",Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd

- ^L. McIlvanney (Spring 2005), "Hugh Blair, Robert Burns, and the Invention of Scottish Literature",Eighteenth-Century Life,29(2): 25–46,doi:10.1215/00982601-29-2-25,S2CID144358210

- ^Robert Burns: "Literary StyleArchived2013-10-16 at theWayback Machine".Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^Robert Burns: "hae meat".Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^Red Star Cafe: "to the Kibble."Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^A. Maunder,FOF Companion to the British Short Story(Infobase Publishing, 2007),ISBN0816074968,p. 374.

- ^I. Brown, "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076,pp. 30–1.

- ^abG. Garlick, "Theatre outside London, 1660–1775", in J. Milling, P. Thomson and J. Donohue, eds,The Cambridge History of British Theatre, Volume 2(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521650682,pp. 170–1.

- ^I. Brown,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813,pp. 229–30.

- ^abL. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813,pp. 301–07.

- ^G. Carruthers,Scottish Literature(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009),ISBN074863309X,pp. 58–9.

- ^M. Lindsay and L. Duncan,The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005),ISBN074862015X,pp. xxxiv–xxxv.

- ^K. S. Whetter,Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008),ISBN0-7546-6142-3,p. 28.

- ^N. Davidson,The Origins of Scottish Nationhood(Pluto Press, 2008),ISBN0-7453-1608-5,p. 136.

- ^abI. Brown,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813,p. 231.

- ^abI. Brown,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813,pp. 185–6.

- ^M. O'Halloran, "National Discourse or Discord? Transformations ofThe Family Legendby Baille, Scott and Hogg ", in S-R. Alker and H. F. Nelson, eds,James Hogg and the Literary Marketplace: Scottish Romanticism and the Working-Class Author(Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009),ISBN0754665690,p. 43.

- ^A. Jarrels, "'Associations respect[ing] the past': Enlightenment and Romantic historicism", in J. P. Klancher,A Concise Companion to the Romantic Age(Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2009),ISBN0631233555,p. 60.

- ^A. Benchimol, ed.,Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010),ISBN0754664465,p. 210.

- ^"Cultural Profile: 19th and early 20th century developments",Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile,archived fromthe originalon 30 September 2011

- ^abcdefghijkl"The Scottish 'Renaissance' and beyond",Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile,archived fromthe originalon 30 September 2011

- ^J. MacDonald, "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328,p. 204.

- ^The Scots Makar,The Scottish Government, 16 February 2004, archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2012,retrieved28 October2007

- ^abJ. MacDonald, "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328,p. 208.

- ^N. Holdsworth, "Case study: Ena Lamont Stewart'sMen Should Weep1947 ", in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328,p. 228.

- ^Royle, Trevor (1983),James & Jim: a Biography of James Kennaway,Mainstream,pp. 185–95,ISBN978-0-906391-46-4

- ^J. MacDonald, "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328,p. 223.

- ^"Duffy reacts to new Laureate post",BBC News,1 May 2009, archived fromthe originalon 30 October 2011

Bibliography[edit]

- Beasley, J. C.,Tobias Smollett: Novelist(University of Georgia Press, 1998),ISBN0820319716.

- Buchan, J.,Crowded with Genius(HarperCollins, 2003),ISBN0-06-055888-1.

- MacDonald, J., "Theatre in Scotland" in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328.

- Bawcutt, P. J. and Williams, J. H.,A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry(Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006),ISBN1-84384-096-0.

- Bell, B., "The national drama, Joanna Baille and the national theatre", in I. Brown,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire, 1707–1918(Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813.

- Benchimol, A., ed.,Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010),ISBN0754664465.

- Bradley, I.,Columba: Pilgrim and Penitent, 597–1997(Wild Goose, 1996),ISBN0-947988-81-5.

- Brown, I.,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007,ISBN0748624813.

- Brown, I., "Introduction: a lively tradition and collective amnesia", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076.

- Brown, I., "Public and private performance: 1650–1800", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076.

- Brown, I., Clancy, T. O., Pittock, M., and Manning, S., eds,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0-7486-1615-2.

- Brown, K. M., "Scottish identity", in B. Bradshaw and P. Roberts, eds,British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003),ISBN0521893615.

- Brown, K. M.,Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from the Reformation to the Revolutions(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004),ISBN0748612998.

- Carpenter, S., "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011),ISBN0748641076.

- Carruthers, G.,Scottish Literature(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009),ISBN074863309X.

- Chedgzoy, K.,Women's Writing in the British Atlantic World(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012),ISBN113946714X.

- Clancy, T. O., "Scotland, the 'Nennian' recension of the Historia Brittonum, and the Lebor Bretnach", in S. Taylor, ed.,Kings, Clerics and Chronicles in Scotland, 500–1297(Dublin/Portland, 2000),ISBN1-85182-516-9.

- Clancy, T. O., "Scottish literature before Scottish literature", in G. Carruthers and L. McIlvanney, eds,The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature(Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2012),ISBN0521189365.

- Clancy, T. O., and Márkus, G.,The Triumph Tree: Scotland's Earliest Poetry, 550–1350(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1998),ISBN0-86241-787-2..

- Corbett, J., McClure, D., and Stuart-Smith, J., "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds,The Edinburgh Companion to Scots(Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003),ISBN0-7486-1596-2.

- Crawford, R.,Scotland's Books: a History of Scottish Literature(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),ISBN0-19-538623-X.

- Davidson, N.,The Origins of Scottish Nationhood(Pluto Press, 2008),ISBN0-7453-1608-5,p. 136.

- Duncan, A. A. M., ed.,The Brus(Canongate, 1997),ISBN0-86241-681-7.

- Frazer, W. O. and Tyrrell A.,Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain(London: Continuum, 2000),ISBN0718500849.

- Fry, M.,Edinburgh(London: Pan Macmillan, 2011),ISBN0-330-53997-3.

- Garlick, G., "Theatre outside London, 1660–1775", in J. Milling, P. Thomson and J. Donohue, eds,The Cambridge History of British Theatre, Volume 2(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521650682.

- Grant, A.,Independence and Nationhood, Scotland 1306–1469(Baltimore: Edward Arnold, 1984).

- Grant, I. F.,The Lordship of the Isles: Wanderings in the Lost Lordship(Mercat, 1982),ISBN0-901824-68-2.

- Gross, C.,The Sources and Literature of English History from the Earliest Times to about 1485(Elibron Classics Series, 1999),ISBN0-543-96628-3.

- Hogg, R. M.,The Cambridge History of the English Language(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994),ISBN0521264782.

- Holdsworth, N., "Case study: Ena Lamont Stewart's Men Should Weep 1947", in B. Kershaw and P. Thomson,The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004),ISBN0521651328.

- Houston, R. A.,Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002),ISBN0521890888.

- Jack, R. D. S., "Poetry under King James VI", in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9.

- Jack, R. D. S.,Alexander Montgomerie(Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1985),ISBN0-7073-0367-2.

- Jackson, C.,Restoration Scotland, 1660–1690: Royalist Politics, Religion and Ideas(Boydell Press, 2003),ISBN0851159303.

- Jarrels, A., "'Associations respect[ing] the past': Enlightenment and Romantic historicism", in J. P. Klancher,A Concise Companion to the Romantic Age(Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2009),ISBN0631233555.

- Jayapalan, N.,History of English Literature(Atlantic, 2001),ISBN81-269-0041-5.

- Jones, C.,A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century(Edinburgh: John Donald, 1993).

- Koch, J. T.,Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia(ABC-CLIO, 2006),ISBN1-85109-440-7.

- Lambdin, R. T., and Lambdin, L. C.,Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature(London: Greenwood, 2000),ISBN0-313-30054-2.

- Lindsay, M. and Duncan, L.,The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005),ISBN074862015X,.

- Lyle, E.,Scottish Ballads(Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2001),ISBN0-86241-477-6.

- MacDonald, J., "Gaelic literature" in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7.

- MacKay, P., Longley, E., and Brearton, F.,Modern Irish and Scottish Poetry(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011),ISBN0521196027.

- Maclachlan, C.,Before Burns(Canongate Books, 2010),ISBN1847674666.

- MacQuarrie, A., "Printing and publishing", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7.

- Maddicott, J. R. and Palliser, D. M., eds,The Medieval State: essays presented to James Campbell(London: Continuum, 2000),ISBN1-85285-195-3.

- Mandell, L., "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed.,The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707–1918)(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),ISBN0748624813.

- Martin, J.,Kingship and Love in Scottish Poetry, 1424–1540(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008),ISBN0-7546-6273-X.

- Mason, R., "Culture: 4 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): general", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7.

- Maunder, A.,FOF Companion to the British Short Story(Infobase Publishing, 2007),ISBN0816074968.

- McCoy, R. C., "Poetry in Scots: Brus to Burns" in C. R. Woodring and J. S. Shapiro, eds,The Columbia History of British Poetry(Columbia University Press, 1994),ISBN0585041555.

- McIlvanney, L. "Hugh Blair, Robert Burns, and the Invention of Scottish Literature",Eighteenth-Century Life,29 (2): 25–46, (Spring 2005), doi:10.1215/00982601-29-2-25.

- Mortimer, I.,The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England(Random House, 2012),ISBN1847921140.

- O'Halloran, M., "National Discourse or Discord? Transformations ofThe Family Legendby Baille, Scott and Hogg ", in S-R. Alker and H. F. Nelson, eds,James Hogg and the Literary Marketplace: Scottish Romanticism and the Working-Class Author(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009),ISBN0754665690.

- Rhodes, N., "Wrapped in the Strong Arm of the Union: Shakespeare and King James" in W. Maley and A. Murphy, eds,Shakespeare and Scotland(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004),ISBN0-7190-6636-0.

- Royle, T.,James & Jim: a Biography of James Kennaway(Mainstream, 1983),ISBN978-0-906391-46-4

- Spiller, M., "Poetry after the Union 1603–1660" in C. Cairns, ed.,The History of Scottish Literature(Aberdeen University Press, 1988), vol. 1,ISBN0-08-037728-9.

- Stringer, K. J., "Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland", in E. J. Cowan and R. A. McDonald, eds,Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages(East Lothian: Tuckwell Press, 2000),ISBN1862321515.

- Thomson, D.,The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian"(Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd, 1952).

- Thomson, T., ed.,Auchinleck Chronicle(Edinburgh, 1819).

- Tobin, T., ed.,The Assembly(Purdue University Press, 1972),ISBN091119830X.

- Treharne, E. M.,Old and Middle English c.890-c.1400: an Anthology(Wiley-Blackwell, 2004),ISBN1-4051-1313-8.

- Van Heijnsbergen, T. "Culture: 7 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): literature", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7.

- Van Heijnsbergen, T., "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed.,The Oxford Companion to Scottish History(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001),ISBN0-19-211696-7.

- Whetter, K. S.,Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008),ISBN0-7546-6142-3.

- Wormald, J.,Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991),ISBN0748602763.

- Yorke, B.,The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c.600–800(Pearson Education, 2006),ISBN0582772923.

External links[edit]

- The Spread of Scottish Printing,digitised items between 1508 and 1900