Sultanate of Rum

Sultanate of Rûm | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1077–1308 | |||||||||||||||||||||

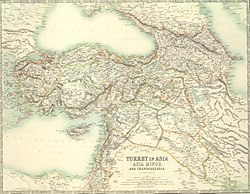

Expansion of the Sultanate,c.1100–1240

Sultanate of Rûm in 1100

Conquered from the Danishmendids up to 1174

Conquered from the Byzantines up to 1182

Other conquests until 1243 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian(official, court, literature, spoken)[1][2] Arabic(numismatics)[3] Byzantine Greek(chancery, spoken)[4] Old Anatolian Turkish(spoken)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam(official),Greek Orthodox(majority of population)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hereditary monarchy Triarchy(1249–1254) Diarchy(1257–1262) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1077–1086 | Suleiman ibn Qutalmish(first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1303–1308 | Mesud II(last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1071 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1077 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1243 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1308 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||||

TheSultanate of Rûm[a]was a culturallyTurco-PersianSunni Muslimstate, established over conqueredByzantineterritories and peoples (Rûm) ofAnatoliaby theSeljuk Turksfollowing theirentry into Anatoliaafter theBattle of Manzikert(1071). The nameRûmwas a synonym for the medievalEastern Roman Empireand its peoples, as it remains in modernTurkish.[8]The name is derived from theAramaic(romī) andParthian(frwm) names forancient Rome,via theGreekῬωμαῖοι(Romaioi).[9]

The Sultanate of Rûm seceded from theSeljuk EmpireunderSuleiman ibn Qutalmishin 1077, just six years after the Byzantine provinces of central Anatolia were conquered at theBattle of Manzikert(1071). It had its capital first atNicaeaand then atIconium.It reached the height of its power during the late 12th and early 13th century, when it succeeded in taking key Byzantine ports on theMediterraneanandBlack Seacoasts. In the east, the sultanate reachedLake Van.Trade through Anatolia from Iran andCentral Asiawas developed by a system ofcaravanserai.Especially strong trade ties with theGenoeseformed during this period. The increased wealth allowed the sultanate to absorb other Turkish states that had been established following the conquest of Byzantine Anatolia:Danishmendids,House of Mengüjek,Saltukids,Artuqids.

The Seljuk sultans bore the brunt of theCrusadesand eventually succumbed to theMongol invasionat the 1243Battle of Köse Dağ.For the remainder of the 13th century, the Seljuks acted as vassals of theIlkhanate.[10]Their power disintegrated during the second half of the 13th century. The last of the Seljuk vassal sultans of the Ilkhanate,Mesud II,was murdered in 1308. The dissolution of the Seljuk state left behind many smallAnatolian beyliks(Turkish principalities), among them that of theOttoman dynasty,which eventually conquered the rest and reunited Anatolia tobecome the Ottoman Empire.

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]Since the 1030s, migratory Turkish groups in search of pastureland had penetrated Byzantine borders into Anatolia.[11]In the 1070s, after thebattle of Manzikert,the Seljuk commanderSuleiman ibn Qutulmish,a distant cousin ofAlp Arslanand a former contender for the throne of theSeljuk Empire,came to power in westernAnatolia.Between 1075 and 1081, he gained control of theByzantinecities of Nicaea (present-dayİznik) and briefly alsoNicomedia(present-dayİzmit). Around two years later, he established a principality that, while initially a Byzantinevassal state,became increasingly independent after six to ten years.[12][13]Nevertheless, it seems that Suleiman was tasked by Byzantine emperorAlexios I Komnenosin 1085 to reconquerAntiochand the former travelled there on a secret route, presumably guided by the Byzantines.[14]

Suleiman tried, unsuccessfully, to conquerAleppoin 1086, and died in theBattle of Ain Salm,either fighting his enemies or by suicide.[15]In the aftermath, Suleiman's sonKilij Arslan Iwas imprisoned and a general of his,Abu'l-Qasim,took power in Nicaea.[16]Following the death of sultanMalik Shahin 1092, Kilij Arslan was released and established himself in his father's territories between 1092 and 1094, possibly with the approval of Malik Shah's son and successorBerkyaruq.[17]

Crusades

[edit]Kilij Arslan, although victorious against thePeople's Crusadeof 1096, was defeated by soldiers of theFirst Crusadeand driven back into south-central Anatolia, where he set up his state with its capital inKonya.He defeated three Crusade contingents in theCrusade of 1101.In 1107, he ventured east and capturedMosulbut died the same year fighting Malik Shah's son,Mehmed Tapar.He was the first Muslim commander against the crusades.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, another Rum Seljuk,Malik Shah(not to be confused with the Seljuk sultan of the same name), captured Konya. In 1116 Kilij Arslan's son,Mesud I,took the city with the help of theDanishmends.[citation needed]Upon Mesud's death in 1156, the sultanate controlled nearly all of central Anatolia.

TheSecond Crusadewas announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe. After crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuk Turks. The main Western Christian source, Odo of Deuil, and Syriac Christian sources claim that the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos secretly hindered the crusaders' progress, particularly in Anatolia, where he is alleged to have deliberately ordered Turks to attack them. However, this alleged sabotage of the Crusade by the Byzantines was likely fabricated by Odo, who saw the Empire as an obstacle, and moreover Emperor Manuel had no political reason to do so. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and participated in 1148 in an ill-advised attack on Damascus, which ended in their retreat. In the end, the crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately have a key influence on the fall of Jerusalem and give rise to the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

Mesud's son,Kilij Arslan II,is the first known Seljuk ruler who is known to have used the title ofsultan[20]and captured the remaining territories aroundSivasandMalatyafrom the last of the Danishmends. At theBattle of Myriokephalonin 1176, Kilij Arslan II also defeated a Byzantine army led byManuel I Komnenos.Despite a temporary occupation of Konya in 1190 by theHoly Roman Empire's forces of theThird Crusade,the sultanate was quick to recover and consolidate its power.[21]During the last years of Kilij Arslan II's reign, the sultanate experienced a civil war withKaykhusraw Ifighting to retain control and losing to his brotherSuleiman IIin 1196.[21][22]

Following Kilij Arslan II's death, the sultanate was divided amongst his sons.[23]Elbistan was given toTughril ibn Kılıç Arslan II,but when Erzurum was taken from the Saltukids at the start of the thirteenth century, he was installed there.[24]Tughril governed Erzurum from 1192 to 1221.[24]During 1211–1212, he broke free from the Seljuk state.[24]In 1230,Jahan Shah bin Tughrilwho was allied to the Khwarazmshah Jalal al-Din, lost theBattle of Yassıçemen,allowing for Erzurum to be annexed by the Seljuk sultanate.[24]

Suleiman IIrallied his vassalemirsand marched against Georgia, with an army of 150,000–400,000 and encamped in theBasianivalley.Tamar of Georgiaquickly marshaled an army throughout her possessions and put it under command of her consort,David Soslan.Georgian troops underDavid Soslanmade a sudden advance intoBasianiand assailed the enemy's camp in 1203 or 1204. In a pitched battle, the Seljukid forces managed to roll back several attacks of the Georgians but were eventually overwhelmed and defeated. Loss of the sultan's banner to the Georgians resulted in a panic within the Seljuk ranks. Süleymanshah himself was wounded and withdrew to Erzurum. Both the Rum Seljuk and Georgian armies suffered heavy casualties, but coordinated flanking attacks won the battle for the Georgians.[25][better source needed]

Suleiman II died in 1204[26]and was succeeded by his sonKilij Arslan III,whose reign was unpopular.[26]Kaykhusraw I seized Konya in 1205 reestablishing his reign.[26]Under his rule and those of his two successors,Kaykaus IandKayqubad I,Seljuk power in Anatolia reached its apogee. Kaykhusraw's most important achievement was the capture of the harbour ofAttalia(Antalya) on the Mediterranean coast in 1207. His son Kaykaus capturedSinop[27]and made theEmpire of Trebizondhis vassal in 1214.[28]He also subjugatedCilician Armeniabut in 1218 was forced to surrender the city of Aleppo, acquired fromal-Kamil.Kayqubadcontinued to acquire lands along the Mediterranean coast from 1221 to 1225.[citation needed]

In the 1220s, he sent an expeditionary force across theBlack SeatoCrimea.[29]In the east he defeated theMengujekidsand began to put pressure on theArtuqids.[citation needed]

Mongol conquest

[edit]Kaykhusraw II(1237–1246) began his reign by capturing the region aroundDiyarbakır,but in 1239 he had to face an uprising led by a popular preacher namedBaba Ishak.After three years, when he had finally quelled the revolt, the Crimean foothold was lost and the state and the sultanate's army had weakened. It is in these conditions that he had to face a far more dangerous threat, that of the expandingMongols.The forces of theMongol EmpiretookErzurumin 1242 and in 1243, the sultan was crushed byBaijuin theBattle of Köse Dağ(a mountain between the cities ofSivasandErzincan), resulting in the Seljuk Turks being forced to swear allegiance to the Mongols and became their vassals.[10]The sultan himself had fled to Antalya after the battle, where he died in 1246; his death started a period of tripartite, and then dual, rule that lasted until 1260.

TheSeljukrealm was divided amongKaykhusraw'sthree sons. The eldest,Kaykaus II(1246–1260), assumed the rule in the area west of the riverKızılırmak.His younger brothers,Kilij Arslan IV(1248–1265) andKayqubad II(1249–1257), were set to rule the regions east of the river under Mongol administration. In October 1256, Bayju defeated Kaykaus II nearAksarayand all of Anatolia became officially subject toMöngke Khan.In 1260 Kaykaus II fled from Konya to Crimea where he died in 1279. Kilij Arslan IV was executed in 1265, andKaykhusraw III(1265–1284) became the nominal ruler of all of Anatolia, with the tangible power exercised either by the Mongols or the sultan's influential regents.

Disintegration

[edit]

The Seljuk state had started to split into smallemirates(beyliks) that increasingly distanced themselves from both Mongol and Seljuk control. In 1277, responding to a call from Anatolia, theMamluk SultanBaibarsraided Anatolia and defeated the Mongols at theBattle of Elbistan,[30]temporarily replacing them as the administrator of the Seljuk realm. But since the native forces who had called him to Anatolia did not manifest themselves for the defense of the land, he had to return to his home base inEgypt,and the Mongol administration was re-assumed, officially and severely. Also, theArmenian Kingdom of Ciliciacaptured the Mediterranean coast fromSelinostoSeleucia,as well as the cities ofMarashandBehisni,from the Seljuk in the 1240s.

Near the end of his reign, Kaykhusraw III could claim direct sovereignty only over lands around Konya. Some of the beyliks (including the early Ottoman state) and Seljuk governors of Anatolia continued to recognize, albeit nominally, the supremacy of the sultan in Konya, delivering thekhutbahin the name of the sultans in Konya in recognition of their sovereignty, and the sultans continued to call themselves Fahreddin,the Pride of Islam.When Kaykhusraw III was executed in 1284, the Seljuk dynasty suffered another blow from internal struggles which lasted until 1303 when the son of Kaykaus II,Mesud II,established himself as sultan inKayseri.He was murdered in 1308 and his son Mesud III soon afterwards. A distant relative to the Seljuk dynasty momentarily installed himself as emir of Konya, but he was defeated and his lands conquered by theKaramanidsin 1328. The sultanate's monetary sphere of influence lasted slightly longer and coins of Seljuk mint, generally considered to be of reliable value, continued to be used throughout the 14th century, once again, including by the Ottomans.

| The comparative genealogy of the Sultanate of Rûm with their contemporary neighbors inCentral Asia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture and society

[edit]

The Seljuk dynasty of Rum, as successors to the Great Seljuks, based its political, religious and cultural heritage on theTurco-Persian traditionandGreco-Roman world,[57]even to the point of naming their sons withNew Persiannames.[58]The Seljuks of Rum had inherited the administrative method of Persian statecraft from the Seljuk Empire, which they would later pass on to the Ottomans.[59]

As an expression of Turco-Persian culture,[60]Rum Seljuks patronizedPersian art,architecture,andliterature.[61]Unlike the Seljuk Empire, the Seljuk sultans of Rum had Persian names such asKay Khosrow,Kay Kawad/Qobad,andKay Kāvus.The bureaucrats and religious elite of their realm were generally Persian.[62]In the 13th century, most Muslim inhabitants in major Anatolian urban hubs reportedly spoke Persian as their main language.[63]It was in this century that the proneness of imitating Iran in terms of administration, religion and culture reached its zenith, encouraged by the major influx of Persian refugees fleeing Mongol invasions, who brought Persian culture with them and were instrumental in creating a "second Iran" in Anatolia.[64][65]Iranian cultural, political, and literary traditions deeply influenced Anatolia in the early 13th century.[66]

Despite their Turkic origins, the Seljuks used Persian for administrative purposes; even their histories, which replaced Arabic, were in Persian.[61]Their usage of Turkish was hardly promoted at all.[61]Even SultanKilij Arslan II,as a child, spoke to courtiers in Persian.[61]Khanbaghi states the Anatolian Seljuks were even more Persianized than the Seljuks that ruled the Iranian plateau.[61]TheRahat al-sudur,the history of the Great Seljuk Empire and its breakup, written in Persian by Muhammad bin Ali Rawandi, was dedicated to SultanKaykhusraw I.[67]Even theTārikh-i Āl-i Saldjūq,an anonymous history of the Sultanate of Rum, was written in Persian.[68]The sultans of Rum were largely not educated in Arabic.[69]This clearly limited the Arab influence, or at least the direct influence, to a relatively small degree.[69]In contrast, Persian literature and Iranian influence expanded because most sultans and even a significant portion of the townspeople knew the language.[69]

One of its most famous Persian writers,Rumi,took his name from the name of the state. Moreover, Byzantine influence in the Sultanate was also significant, since Byzantine Greek aristocracy remained part of the Seljuk nobility, and the native Byzantine (Rûm) peasants remained numerous in the region.[70][71]Based on their genealogy, it appears that the Seljuk sultans favored Christian ladies, just like the early Ottoman sultans. Within the Seljuk harem, Greek women were the most dominant.[72]Cultural Turkification in Anatolia first started during the 14th-century, particularly during the gradual rise of theOttomans.[73]With a population that includedByzantine Greeks,Armenians,Kurds,Turks, and Persians, the Seljuks were very successful between 1220 and 1250 and set the groundwork for later Islamization of Anatolia.[74]

Architecture

[edit]

In their construction ofcaravanserais,madrasasandmosques,the Rum Seljuks translated the Iranian Seljuk architecture of bricks and plaster into the use of stone.[75]Among these, thecaravanserais(orhans), used as stops, trading posts and defense for caravans, and of which about a hundred structures were built during the Anatolian Seljuk period, are particularly remarkable. Along with Persian influences, which had an indisputable effect,[76]Seljuk architecture was inspired by local Byzantine architects, for example in theCelestial Mosque in Sivas,and byArmenian architecture.[77]Anatolian architecture represents some of the most distinctive and impressive constructions in the entire history of Islamic architecture. Later, this Anatolian architecture would be inherited by theSultanate of India.[78]

The largest caravanserai is theSultan Han(built-in 1229) on the road between the cities of Konya and Aksaray, in the township ofSultanhanı,covering 3,900 m2(42,000 sq ft). Two caravanserais carry the nameSultan Han,the other onebeing between Kayseri and Sivas. Furthermore, apart from Sultanhanı, five other towns across Turkey owe their names to caravanserais built there. These are Alacahan inKangal,Durağan,HekimhanandKadınhanı,as well as the township of Akhan within theDenizlimetropolitan area. The caravanserai of Hekimhan is unique in having, underneath the usual inscription inArabicwith information relating to the tower, two further inscriptions inArmenianandSyriac,since it was constructed by the sultanKayqubad I's doctor (hekim), who is thought to have been aChristian convert to Islam.There are other particular cases, like the settlement inKalehisarcontiguous to an ancientHittitesite nearAlaca,founded by the Seljuk commanderHüsameddin Temurlu,who had taken refuge in the region after the defeat in theBattle of Köse Dağand had founded a township comprising a castle, a madrasa, a habitation zone and a caravanserai, which were later abandoned apparently around the 16th century. All but the caravanserai, which remains undiscovered, was explored in the 1960s by the art historianOktay Aslanapa,and the finds as well as several documents attest to the existence of a vivid settlement in the site, such as a 1463 Ottomanfirmanwhich instructs the headmaster of the madrasa to lodge not in the school but in the caravanserai.[citation needed]

The Seljuk palaces, as well as their armies, were staffed withghilmān(Arabic:غِلْمَان), singularghulam), slave-soldiers taken as children from non-Muslim communities, mainly Greeks from former Byzantine territories. The practice of keeping ghilmān may have offered a model for the laterdevşirmeduring the time of theOttoman Empire.[79]

Numismatics

[edit]The earliest documented Rum Seljuq copper coins were made in the first part of the twelfth century in Konya and the eastern Anatolian emirates.[80]Extensive numismatic evidence suggests that, starting in the middle of the thirteenth century and continuing until the end of the Seljuk dynasty, silver-producing mints and silver coinage flourished, particularly in central and eastern Anatolia.[81]

Most of Kilij Arslan II's coins were minted in Konya between 1177–78 and 1195, with a small amount also occurring in Sivas, which the Rum Seljuks conquered from the Danishmendids.[23]Sivas may have started minting coins in 1185–1186.[23]The majority of Kılıj Arslan II's coins are silverdirhams;however, there are also a fewdinarsand one or twofulūs(small copper coins) issues.[23]Following his death the sultanate was divided among his sons. Muhyiddin Mesut, son of Kilij Arslan II, minted coins in the northwesterly cities of Ankara, Çankırı, Eskişehir, and Kaztamunu from 1186 to 1200.[23]Tughril ibn Kılıç Arslan II's reign in Erzurum, another son of Kilij Arslan II, minted silver dirhams in 1211–1212.[23]

The sun-lion and the equestrian are the two central motifs in the Rum Seljuq numismatic figural repertoire.[82]The image of a horseman with two more arrows ready and his bow taut represents strength and control and is a representation of the ideal Seljuq king of the Great Age.[82]The image initially appeared on Rum Seljuq copper coins in the late eleventh century.[82]The first to add equestrian iconography to silver and gold coins wasSuleiman II of Rûm(r. 1196–1204).[82]Antalya minted coins withKaykaus I's name from November 1261 to November 1262.[83]Between 1211 and 1219, the bulk of his coins are minted at Konya and Sivas.[23]

A significant portion of the Islamic Near East may have experienced a "silver famine" owing to little, or very little, silver mintings from the eleventh and most of the twelfth centuries. However, at the start of the thirteenth century a "silver flood" occurred in Rum Seljuq territory when Anatolian silver mines were discovered.[84]The fineness of Rum Seljuqdirhamsis similar to that ofdinars;frequently, both were struck using the same dies.[84]The Seljuq silver coinage's superior quality and prominence contributed to the dynasty's affluence throughout the early part of the thirteenth century and explains why it served as a kind of anchor for the local "currency community."[85]TheEmpire of TrebizondandArmenian Kingdom of Ciliciasilver coins were modeled after the fineness and weight specifications of Rum Seljuq coins.[82]

Dynasty

[edit]

| History ofTurkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of the Turkic peoplespre–14th century |

|---|

|

As regards with the names of the sultans, there are variants in form and spelling depending on the preferences displayed by one source or the other, either for fidelity intransliteratingthePersian variantof theArabic scriptwhich the sultans used, or for a rendering corresponding to the modernTurkishphonology and orthography. Some sultans had two names that they chose to use alternatively in reference to their legacy. While the two palaces built by Alaeddin Keykubad I carry the namesKubadabad Palaceand Keykubadiye Palace, he named his mosque in Konya asAlâeddin Mosqueand the port city ofAlanyahe had captured as "Alaiye".Similarly, the medrese built byKaykhusraw Iin Kayseri, within the complex (külliye) dedicated to his sisterGevher Nesibe,was named Gıyasiye Medrese, and the one built byKaykaus Iin Sivas as Izzediye Medrese.[citation needed]

| Sultan | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1.Qutalmish | 1060–1064 | Contended withAlp Arslanfor succession to theImperial Seljukthrone. |

| 2.Suleiman ibn Qutulmish | 1075–1077de factorules Turkmen aroundİznikandİzmit; 1077–1086 recognised Sultan ofRûmbyMalik-Shah Iof theGreat Seljuks |

Founder of Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate with capital in İznik |

| 3.Kilij Arslan I | 1092–1107 | First sultan inKonya |

| 4.Malik Shah | 1107–1116 | |

| 5.Masud I | 1116–1156 | |

| 6.'Izz al-Din Kilij Arslan II | 1156–1192 | |

| 7.Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I | 1192–1196 | First reign |

| 8.Rukn al-Din Suleiman II | 1196–1204 | |

| 9.Kilij Arslan III | 1204–1205 | |

| (7.)Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I | 1205–1211 | Second reign |

| 10.'Izz al-Din Kayka'us I | 1211–1220 | |

| 11.'Ala al-Din Kayqubad I | 1220–1237 | |

| 12.Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw II | 1237–1246 | After his death, sultanate split until 1260 whenKilij Arslan IVremained the sole ruler |

| 13.'Izz al-Din Kayka'us II | 1246–1262 | |

| 14.Rukn al-Din Kilij Arslan IV | 1249–1266 | |

| 15.'Ala al-Din Kayqubad II | 1249–1254 | |

| 16.Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw III | 1266–1284 | |

| 17.Giyath al-Din Masud II | 1282–1296 | First reign |

| 18.'Ala al-Din Kayqubad III | 1298–1302 | |

| (17.)Giyath al-Din Masud II | 1303–1308 | Second reign |

See also

[edit]- Babai Revolt

- Byzantine–Seljuk Wars

- List of battles involving the Seljuk Empire

- Rûm Eyalet,Ottoman Empire

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^Grand VizierSāhīp Shams ad-Dīn Īsfahānīruled the country on behalf of ʿIzz ad-DīnKay Kāwus IIbetween 1246 and 1249

- ^Grand VizierParwānaMu‘in al-Din Suleymanruled the country on behalf of Ghiyāth ad-DīnKay Khusraw IIIbetween 1266 and 2 August 1277 (1Rabi' al-awwal676)

- ^Between 1246 and 1249 ʿIzz ad-DīnKay Kāwus IIreigned alone

- ^ʿIzz ad-DīnKay Kāwus IIwas defeated on October 14, 1256 inSultanhanı(Sultan Han,Aksaray) and he acceded to the throne on May 1, 1257 again after the departure ofBaiju NoyanfromAnatolia

- ^Between 1262 and 1266 Rukn ad-DīnKilij Arslan IVreigned alone

- ^Between 1249 and 1254 triple reign of three brothers

- ^According toİbn Bîbî,el-Evâmirü’l-ʿAlâʾiyye,p. 727. (10Dhu al-Hijjah675 – 17Muharram676)

- ^According to Yazıcıoğlu Ali,Tevârih-i Âl-i Selçuk,p. 62. (10Dhu al-Hijjah677 – 17Muharram678)

References

[edit]- ^Grousset, Rene,The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia,(Rutgers University Press, 2002), 157; "...the Seljuk court at Konya adopted Persian as its official language."

- ^Bernard Lewis,Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire,(University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 29; "The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian...".

- ^Mecit 2013,p. 82.

- ^Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2013), 132; "The official use of the Greek language by the Seljuk chancery is well known".

- ^Mehmed Fuad Koprulu (2006).Early Mystics in Turkish Literature.p. 207.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 265.

- ^Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017).Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, ca. 1040–1130.New York: Routledge. p. 15.

- ^Alexander Kazhdan, "Rūm"The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium(Oxford University Press, 1991), vol. 3, p. 1816. Paul Wittek,Rise of the Ottoman Empire,Royal Asiatic Society Books, Routledge (2013),p. 81: "This state too bore the name of Rûm, if not officially, then at least in everyday usage, and its princes appear in the Eastern chronicles under the nameSeljuks of Rûm(Ar.:Salâjika ar-Rûm). A. Christian Van Gorder,Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iranp. 215: "The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanateRûmbecause it had been established on territory long considered 'Roman',i.e.Byzantine, by Muslim armies. "

- ^Shukurov 2020,p. 145.

- ^abJohn Joseph Saunders,The History of the Mongol Conquests(University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971), 79.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 12.

- ^Sicker, Martin,The Islamic world in ascendancy: from the Arab conquests to the siege of Vienna,(Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000), 63–64.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 72.

- ^Frankopan 2013,p. 51.

- ^Frankopan 2013,p. 52.

- ^Sicker, Martin,The Islamic world in ascendancy: from the Arab conquests to the siege of Vienna,(Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000), 65.

- ^Frankopan 2013,pp. 68–69.

- ^These knights were equipped with long swords and bows, and for protection used large shields ( "kite-shields" ), lamellar armour andhauberkmailGorelik, Michael (1979).Oriental Armour of the Near and Middle East from the Eighth to the Fifteenth Centuries as Shown in Works of Art (in Islamic Arms and Armour).London: Robert Elgood. p. Fig. 38.ISBN978-0859674706.

- ^Sabuhi, Ahmadov Ahmad oglu (July–August 2015)."The miniatures of the manuscript" Varka and Gulshah "as a source for the study of weapons of XII–XIII centuries in Azerbaijan".Austrian Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences(7–8): 14–16.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 73.

- ^abAnatolia in the period of the Seljuks and the "beyliks",Osman Turan,The Cambridge History of Islam,Vol. 1A, ed. P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 244–245.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 29.

- ^abcdefgSinclair 2020,p. 41.

- ^abcdSinclair 2020,pp. 137–138.

- ^Alexander Mikaberidze,Historical Dictionary of Georgia,(Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 184.

- ^abcClaude Cahen,The Formation of Turkey: The Seljukid Sultanate of Rum: Eleventh to Fourteenth,transl. & ed. P.M. Holt, (Pearson Education Limited, 2001), 42.

- ^Tricht 2011,p. 355.

- ^Ring, Watson & Schellinger 1995,p. 651.

- ^A.C.S. Peacock,"The Saliūq Campaign against the Crimea and the Expansionist Policy of the Early Reign of'Alā' al-Dīn Kayqubād",Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,Vol. 16 (2006), pp. 133–149.

- ^Kastritsis 2013,p. 26.

- ^Zahîrüddîn-i Nîsâbûrî,Selcûḳnâme,(Muhammed Ramazânî Publications),Tahran1332, p. 10.

- ^Reşîdüddin Fazlullāh-ı Hemedânî,Câmiʿu’t-tevârîḫ,(Ahmed Ateş Publications),Ankara1960, vol. II/5, p. 5.

- ^Râvendî, Muhammed b. Ali,Râhatü’s-sudûr,(Ateş Publications), vol. I, p. 85.

- ^Müstevfî,Târîḫ-i Güzîde,(Nevâî Publications), p. 426.

- ^Osman Gazi Özgüdenli (2016).MÛSÂ YABGU.Vol. EK-2.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 324–325.

- ^abcdSevim, Ali (2010).SÜLEYMAN ŞAH I(PDF).Vol. 38.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 103–105.ISBN978-9-7538-9590-3.

- ^abcFaruk Sümer (2002).KUTALMIŞ(PDF).Vol. 26.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 480–481.ISBN978-9-7538-9406-7.

- ^abOsman Gazi Özgüdenli (2016)."MÛSÂ YABGU".TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Supplement 2 (Kâfûr, Ebü'l-Misk – Züreyk, Kostantin)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 324–325.ISBN978-975-389-889-8.

- ^Beyhakī,Târîḫ,(Behmenyâr), p. 71.

- ^abcdefghSümer, Faruk (2009).ANADOLU SELÇUKLULARI(PDF).Vol. 36.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 380–384.ISBN978-9-7538-9566-8.

- ^Sevim, Ali (1993)."ÇAĞRI BEY"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 8 (Ci̇lve – Dârünnedve)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 183–186.ISBN978-975-389-435-7.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (2009)."SELÇUKLULAR"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 365–371.ISBN978-975-389-566-8.

- ^Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2002).KAVURD BEY(PDF).Vol. 25.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 73–74.ISBN978-9-7538-9403-6.

- ^abcdefSümer, Faruk (2009).Kirman Selçuks(PDF).Vol. 36.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 377–379.ISBN978-9-7538-9566-8.

- ^Bezer, Gülay Öğün (2011)."TERKEN HATUN, the mother of MAHMÛD I"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 40 (Tanzi̇mat – Teveccüh)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 510.ISBN978-975-389-652-8.Terken Khatun (wife of Malik-Shah I).

- ^Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2004)."MELİKŞAH"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 29 (Mekteb – Misir Mevlevîhânesi̇)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 54–57.ISBN978-975-389-415-9.

- ^Özaydın, Abdülkerim (1992)."BERKYARUK"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 5 (Balaban – Beşi̇r Ağa)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 514–516.ISBN978-975-389-432-6.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (2009).SELÇUKLULAR(PDF).Vol. 36.Istanbul:TDVİslâm Ansiklopedisi.pp. 365–371.ISBN978-9-7538-9566-8.

- ^Enverî,Düstûrnâme-i Enverî,pp. 78–80, 1464.

- ^abcdefghiSümer, Faruk (2009)."IRAK SELÇUKLULARI"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 387.ISBN978-975-389-566-8.

- ^Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2003)."MAHMÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 27 (Kütahya Mevlevîhânesi̇ – Mani̇sa)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 371–372.ISBN978-975-389-408-1.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (2012)."TUĞRUL I"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 41 (Tevekkül – Tüsterî)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 341–342.ISBN978-975-389-713-6.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (2004)."MES'ÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 29 (Mekteb – Misir Mevlevîhânesi̇)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 349–351.ISBN978-975-389-415-9.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (1991)."ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 3 (Amasya – Âşik Mûsi̇ki̇si̇)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 404–406.ISBN978-975-389-430-2.

- ^Sümer, Faruk (2012)."Ebû Tâlib TUĞRUL b. ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL"(PDF).TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 41 (Tevekkül – Tüsterî)(in Turkish). Istanbul:Turkiye Diyanet Foundation,Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 342–344.ISBN978-975-389-713-6.

- ^Shukurov 2016,p. 108–109.

- ^Saljuqs: Saljuqs of Anatolia,Robert Hillenbrand,The Dictionary of Art,Vol.27, Ed. Jane Turner, (Macmillan Publishers Limited, 1996), 632.

- ^Rudi Paul Lindner,Explorations in Ottoman Prehistory,(University of Michigan Press, 2003), 3.

- ^Itzkowitz 1980,p. 48.

- ^Lewis, Bernard,Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire,p. 29,

Even when the land of Rum became politically independent, it remained a colonial extension of Turco-Persian culture which had its centers in Iran and Central Asia... The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian...

- ^abcdeKhanbaghi 2016,p. 202.

- ^Hillenbrand 2020,p. 15.

- ^Shukurov 2020,p. 155.

- ^Hillenbrand 2021,p. 211 "Inner Anatolia was now set to become Muslim gradually, and this process occurred under the leadership of the Turks. In Anatolia, as elsewhere, the Seljuq rulers drank in Persian cultural ways in their cities. This tendency to copy Iran in administration, religion and culture reached its height in the thirteenth century with the fuller development of the Seljuq state in Anatolia and the influx of Persian refugees to Anatolian cities. Thus ‘a second Iran’ was created in Anatolia. It is food for thought that, while it was the Turks who conquered and settled the land of Anatolia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, it was the Persians who were instrumental in bringing to these territories a developed Islamic religious and secular culture. (...)Quote in French:Les réfugiés iraniens qui entrèrent en grand nombre en Anatolie à la suite des invasions mongoles de l’Iran – les fonctionnaires, les poètes, les Sufis et, avant tout, les cadres religieux – transformèrent de l’intérieur la culture urbaine de cette région. "

- ^Findley, Carter V. (2005).The Turks in World History.Oxford University Press, USA. p. 72.ISBN978-0-19-517726-8.

Meanwhile, amid the migratory swarm that Turkified Anatolia, the dispersion of learned men from the Persian-speaking east paradoxically made the Seljuk court at Konya a new center for Perso-Islamic court culture.

- ^Hickman & Leiser 2016,p. 278.

- ^Richards & Robinson 2003,p. 265.

- ^Crane 1993,p. 2.

- ^abcCahen & Holt 2001,p. 163.

- ^Shukurov, Rustam (2011), "The Oriental Margins of the Byzantine World: a Prosopographical Perspective", in Herrin, Judith; Saint-Guillain, Guillaume (eds.),Identities and Allegiances in the Eastern Mediterranean After 1204,Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., pp. 181–191,ISBN978-1-4094-1098-0

- ^Korobeinikov, Dimitri (2007),"A sultan in Constantinople: the feasts of Ghiyath al-Din Kay-Khusraw I",in Brubaker, Leslie; Linardou, Kallirroe (eds.),Eat, Drink, and be Merry (Luke 12:19): Food and Wine in Byzantium: Papers of the 37th Annual Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, in Honour of Professor A.A.M. Bryer,Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 96,ISBN978-0-7546-6119-1

- ^A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz,The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East,(I.B. Tauris, 2015), 121.

- ^Hillenbrand 2021,p. 211.

- ^Hillenbrand 2021,p. 333.

- ^Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan (2004), "West Asia: 1000–1500", in Onians, John (ed.),Atlas of World Art,Laurence King Publishing, p. 130

- ^Architecture (Muhammadan),H. Saladin,Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics,Vol.1, Ed. James Hastings and John Alexander, (Charles Scribner's son, 1908), 753.

- ^Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods,Robert Bedrosian,The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times: The Dynastic Periods from Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century,Vol. I, Ed. Richard Hovannisian, (St. Martin's Press, 1999), 250.

- ^Lost in Translation: Architecture, Taxonomy, and the "Eastern Turks",Finbarr Barry Flood,Muqarnas: History and Ideology: Architectural Heritage of the "Lands of Rum,96.

- ^Rodriguez, Junius P.(1997).The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery.ABC-CLIO. p.306.ISBN978-0-87436-885-7.

- ^Beihammer 2017,p. 20.

- ^Pamuk 2000,p. 28.

- ^abcdeCanby et al. 2016,p. 69.

- ^Shukurov 2016,p. 104.

- ^abCanby et al. 2016,p. 68.

- ^Canby et al. 2016,pp. 68–69.

Sources

[edit]- Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017).Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim–Turkish Anatolia, Ca. 1040–1130.Routledge.

- Bosworth, C. E.(2004).The New Islamic Dynasties: a Chronological and Genealogical Manual.Edinburgh University Press.ISBN0-7486-2137-7.

- Bektaş, Cengiz (1999).Selcuklu Kervansarayları, Korunmaları Ve Kullanlmaları üzerine bir öneri: A Proposal regarding the Seljuk Caravanserais, Their Protection and Use(in Turkish and English). Yapı-Endüstri Merkezi Yayınları.ISBN975-7438-75-8.

- Cahen, Claude; Holt, Peter Malcolm (2001).The Formation of Turkey. The Seljukid Sultanate of Rūm: Eleventh to Fourteenth Century.Longman.

- Canby, Sheila R.; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Maryam; Peacock, A.C.S., eds. (2016).Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs.Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Crane, H. (1993). "Notes on Saldjūq Architectural Patronage in Thirteenth Century Anatolia".Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient.36(1): 1–57.doi:10.1163/156852093X00010.

- Frankopan, Peter (2013).The First Crusade: The call from the East.London: Vintage.ISBN9780099555032.

- Hickman, Bill; Leiser, Gary (2016).Turkish Language, Literature, and History: Travelers' Tales, Sultans, and Scholars Since the Eighth Century.Routledge.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2020). "What is Special about Seljuq History?". In Canby, Sheila; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Martina (eds.).The Seljuqs and their Successors: Art, Culture and History.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 6–16.ISBN978-1474450348.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2021).The Medieval Turks: Collected Essays.Edinburgh University Press.ISBN978-1474485944.

- Itzkowitz, Norman(1980).Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0226388069.

- Kastritsis, Dimitris (2013). "The Historical Epic" Ahval-i Sultan Mehemmed "(The Tales of Sultan Mehmed) in the Context of Early Ottoman Historiography".Writing History at the Ottoman Court: Editing the Past, Fashioning the Future.Indiana University Press.

- Khanbaghi, Aptin (2016). "Champions of the Persian Language: The Mongols or the Turks?". In De Nicola, Bruno; Melville, Charles (eds.).The Mongols' Middle East: Continuity and Transformation in Ilkhanid Iran.Brill.

- Mecit, Songul (2013).The Rum Seljuqs: Evolution of a Dynasty.Taylor & Francis.

- Pamuk, Sevket (2000).A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire.Cambridge University Press.

- Richards, Donald S.; Robinson, Chase F. (2003).Texts, documents, and Artefacts.Brill.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul, eds. (1995).Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places.Vol. 3. Routledge.

- Shukurov, Rustam (2016).The Byzantine Turks, 1204–1461.Brill.

- Shukurov, Rustam (2020). "Grasping the Magnitude: Saljuq Rum between Byzantium and Persia". In Canby, Sheila; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Martina (eds.).The Seljuqs and their Successors: Art, Culture and History.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 144–162.ISBN978-1474450348.

- Sinclair, Thomas (2020).Eastern Trade and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages: Pegolotti’s Ayas.Routledge.

- Tricht, Filip Van (2011).The Latin Renovatio of Byzantium: The Empire of Constantinople (1204–1228).Translated by Longbottom, Peter. Brill.

External links

[edit]- Yavuz, Ayşıl Tükel."The concepts that shape Anatolian Seljuq caravanserais"(PDF).ArchNet.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2007-07-04.

- "List of Seljuk edifices".ArchNet.Archived fromthe originalon 2007-04-05.

- Katharine Branning."Examples of caravanserais built by the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate".Turkish Hans.