Shark

| Sharks Temporal range:Possible records extend back to Early Permian

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Agrey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Infraclass: | Euselachii |

| Clade: | Neoselachii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha Nelson,1984 |

| Orders | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Sharksare a group ofelasmobranchfish characterized by acartilaginous skeleton,five to sevengill slitson the sides of thehead,andpectoral finsthat are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within thecladeSelachimorpha(orSelachii) and are thesister groupto theBatoidea(raysand kin). Some sources extend the term "shark" as an informal category including extinct members ofChondrichthyes(cartilaginous fish) with a shark-like morphology, such ashybodonts.Shark-like chondrichthyans such asCladoselacheandDoliodusfirst appeared in theDevonianPeriod (419–359 million years), though some fossilized chondrichthyan-like scales are as old as theLate Ordovician(458–444 million years ago).[1]The earliest confirmed modern sharks (selachimorphs) are known from theEarly Jurassicaround200million years ago,with the oldest known member beingAgaleus,though records of true sharks may extend back as far as thePermian.[2]

Sharks range in size from the smalldwarf lanternshark(Etmopterus perryi), a deep sea species that is only 17 centimetres (6.7 in) in length, to thewhale shark(Rhincodon typus), the largest fish in the world, which reaches approximately 12 metres (40 ft) in length.[3]They are found in all seas and are common to depths up to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft). They generally do not live in freshwater, although there are a few known exceptions, such as thebull sharkand theriver sharks,which can be found in both seawater and freshwater (it is worth mentioning that theGanges sharkis restricted to freshwater).[4]Sharks have a covering ofdermal denticlesthat protects their skin from damage andparasitesin addition to improving theirfluid dynamics.They have numerous sets of replaceable teeth.[5]

Several species areapex predators,which are organisms that are at the top of theirfood chain.Select examples include thebull shark,tiger shark,great white shark,mako sharks,thresher sharks,andhammerhead sharks.

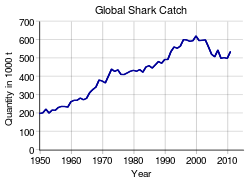

Sharks are caught by humans forshark meatorshark fin soup.Many shark populations are threatened by human activities. Since 1970, shark populations have been reduced by 71%, mostly fromoverfishing.[6]

Etymology

Until the 16th century,[7]sharks were known to mariners as "sea dogs".[8]This is still evidential in several species termed "dogfish,"or theporbeagle.

The etymology of the wordsharkis uncertain, the most likely etymology states that the original sense of the word was that of "predator, one who preys on others" from theDutchschurk,meaning 'villain, scoundrel' (cf.card shark,loan shark,etc.), which was later applied to the fish due to its predatory behaviour.[9]

A now disproven[original research?]theory is that it derives from theYucatec Mayawordxook(pronounced[ʃoːk]), meaning 'shark'.[10] Evidence for this etymology came from theOxford English Dictionary,which notessharkfirst came into use after SirJohn Hawkins' sailors exhibited one in London in 1569 and posted "sharke"to refer to the large sharks of theCaribbean Sea.However, theMiddle English Dictionaryrecords an isolated occurrence of the wordshark(referring to a sea fish) in a letter written byThomas Beckingtonin 1442, which rules out a New World etymology.[11][original research?]

Evolutionary history

Fossil record

The oldesttotal-groupchondrichthyans, known asacanthodiansor "spiny sharks", appeared during the EarlySilurian,around 439 million years ago.[12]The oldest confirmed members ofElasmobranchiisensu lato(the group containing all cartilaginous fish more closely related to modern sharks and rays than tochimaeras) appeared during theDevonian.[13]Anachronistidae,the oldest probable representatives of Neoselachii, the group containing modern sharks (Selachimorpha) and rays (Batoidea) to the exclusion of most extinct elasmobranch groups, date to theCarboniferous.[14]Selachiimorpha and Batoidea are suggested by some to have diverged during theTriassic.[15]Fossils of the earliest true sharks may have appeared during thePermian,based on remains of "synechodontiforms"found in the Early Permian of Russia,[16]but if remains of "synechodontiformes" from the Permian and Triassic are true sharks, they only had low diversity. Modern shark orders first appeared during the Early Jurassic, and during the Jurassic true sharks underwent great diversification.[17]Selachimorphs largely replaced thehybodonts,which had previously been a dominant group of shark-like fish during the Triassic and Early Jurassic.[18]

Taxonomy

| Phylogeny of living shark orders based onmitochondrial DNA[19] |

Sharks belong to thecladeSelachimorpha in thesubclassElasmobranchiiin theclassChondrichthyes.The Elasmobranchii also includeraysandskates;the Chondrichthyes also includeChimaeras.It was thought that the sharks form apolyphyleticgroup: some sharks are more closely related to rays than they are to some other sharks,[20]but current molecular studies support monophyly of both groups of sharks and batoids.[21][22]

The clade Selachimorpha is divided into the superorders Galea (orGaleomorphii), and Squalea (orSqualomorphii). The Galeans are theHeterodontiformes,Orectolobiformes,Lamniformes,andCarcharhiniformes.Lamnoids and Carcharhinoids are usually placed in oneclade,but recent studies show that Lamnoids and Orectoloboids are a clade. Some scientists now think that Heterodontoids may be Squalean. The Squaleans are divided intoHexanchiformesand Squalomorpha. The former includescow sharkandfrilled shark,though some authors propose that both families be moved to separate orders. The Squalomorpha contains theSqualiformesand the Hypnosqualea. The Hypnosqualea may be invalid. It includes theSquatiniformes,and the Pristorajea, which may also be invalid, but includes thePristiophoriformesand theBatoidea.[20][23]

There are more than 500 species of sharks split across thirteenorders,including several orders of sharks that have gone extinct:[23][24]

- Carcharhiniformes:Commonly known asground sharks,the order includes theblue,tiger,bull,grey reef,blacktip reef,Caribbean reef,blacktail reef,whitetip reef,andoceanic whitetip sharks(collectively called therequiem sharks) along with thehoundsharks,catsharks,andhammerhead sharks.They are distinguished by an elongated snout and anictitating membranewhich protects the eyes during an attack.

- Heterodontiformes:They are generally referred to as thebullheadorhorn sharks.

- Hexanchiformes:Examples from this group include thecow sharksandfrilled sharks,which somewhat resembles a marine snake.

- Lamniformes:They are commonly known as themackerel sharks.They include thegoblin shark,basking shark,megamouth shark,thethresher sharks,shortfinandlongfin mako sharks,andgreat white shark.They are distinguished by their large jaws andovoviviparousreproduction. The Lamniformes also include the extinctmegalodon,Otodus megalodon.

- Orectolobiformes:They are commonly referred to as thecarpet sharks,includingzebra sharks,nurse sharks,wobbegongs,and thewhale shark.

- Pristiophoriformes:These are thesawsharks,with an elongated, toothed snout that they use for slashing their prey.

- Squaliformes:This group includes thedogfish sharksandroughsharks.

- Squatiniformes:Also known asangel sharks,they are flattened sharks with a strong resemblance tostingraysandskates.

- Echinorhiniformes:This group includes theprickly sharkandbramble shark.Phylogenetic placement of this group has been ambiguous in scientific studies.[25]They are sometimes given their own order, Echinorhiniformes.[24]

Anatomy

Teeth

Shark teeth are embedded in thegumsrather than directly affixed to the jaw, and are constantly replaced throughout life. Multiple rows of replacement teeth grow in a groove on the inside of the jaw and steadily move forward in comparison to aconveyor belt;some sharks lose 30,000 or more teeth in their lifetime. The rate of tooth replacement varies from once every 8 to 10 days to several months. In most species, teeth are replaced one at a time as opposed to the simultaneous replacement of an entire row, which is observed in thecookiecutter shark.[26]

Tooth shape depends on the shark's diet: those that feed onmollusksandcrustaceanshave dense and flattened teeth used for crushing, those that feed on fish have needle-like teeth for gripping, and those that feed on larger prey such asmammalshave pointed lower teeth for gripping and triangular upper teeth withserratededges for cutting. The teeth of plankton-feeders such as the basking shark are small and non-functional.[27]

Skeleton

Shark skeletons are very different from those ofbony fishandterrestrial vertebrates.Sharks and othercartilaginous fish(skatesandrays) have skeletons made ofcartilageandconnective tissue.Cartilage is flexible and durable, yet is about half the normal density of bone. This reduces the skeleton's weight, saving energy.[28]Because sharks do not have rib cages, they can easily be crushed under their own weight on land.[29]

Jaw

Thejawsof sharks, like those of rays and skates, are not attached to thecranium.The jaw's surface (in comparison to the shark's vertebrae and gill arches) needs extra support due to its heavy exposure to physical stress and its need for strength. It has a layer of tiny hexagonal plates called "tesserae",which are crystal blocks of calcium salts arranged as a mosaic.[30]This gives these areas much of the same strength found in the bony tissue found in other animals.

Generally sharks have only one layer of tesserae, but the jaws of large specimens, such as the bull shark, tiger shark, and the great white shark, have two to three layers or more, depending on body size. The jaws of a large great white shark may have up to five layers.[28]In therostrum(snout), the cartilage can be spongy and flexible to absorb the power of impacts.

Fins

Fin skeletons are elongated and supported with soft and unsegmented rays named ceratotrichia, filaments of elastic protein resembling the horny keratin in hair and feathers.[31]Most sharks have eight fins. Sharks can only drift away from objects directly in front of them because their fins do not allow them to move in the tail-first direction.[29]

Dermal denticles

Unlike bony fish, sharks have a complex dermal corset made of flexible collagenous fibers and arranged as a helical network surrounding their body. This works as an outer skeleton, providing attachment for their swimming muscles and thus saving energy.[32]Their dermal teeth give themhydrodynamicadvantages as they reduce turbulence when swimming.[33]Some species of shark have pigmented denticles that form complex patterns like spots (e.g.Zebra shark) and stripes (e.g.Tiger shark). These markings are important forcamouflageand help sharks blend in with their environment, as well as making them difficult for prey to detect.[34]For some species, dermal patterning returns to healed denticles even after they have been removed by injury.[35]

Tails

Tailsprovide thrust, making speed and acceleration dependent on tail shape.Caudal finshapes vary considerably between shark species, due to their evolution in separate environments. Sharks possess aheterocercalcaudal fin in which thedorsalportion is usually noticeably larger than theventralportion. This is because the shark'svertebral columnextends into that dorsal portion, providing a greater surface area for muscle attachment. This allows more efficientlocomotionamong these negatively buoyant cartilaginous fish. By contrast, most bony fish possess ahomocercalcaudal fin.[36]

Tiger sharks have a large upperlobe,which allows for slow cruising and sudden bursts of speed. The tiger shark must be able to twist and turn in the water easily when hunting to support its varied diet, whereas theporbeagle shark,which hunts schooling fish such asmackerelandherring,has a large lower lobe to help it keep pace with its fast-swimming prey.[37]Other tail adaptations help sharks catch prey more directly, such as the thresher shark's usage of its powerful, elongated upper lobe to stun fish and squid.

Physiology

Buoyancy

Unlike bony fish, sharks do not have gas-filled swim bladders for buoyancy. Instead, sharks rely on a large liver filled with oil that containssqualene,and their cartilage, which is about half the normal density of bone.[32]Their liver constitutes up to 30% of their total body mass.[38]The liver's effectiveness is limited, so sharks employdynamic liftto maintain depth while swimming.Sand tiger sharksstore air in their stomachs, using it as a form of swim bladder. Bottom-dwelling sharks, like thenurse shark,have negative buoyancy, allowing them to rest on the ocean floor.

Some sharks, if inverted or stroked on the nose, enter a natural state oftonic immobility.Researchers use this condition to handle sharks safely.[39]

Respiration

Like other fish, sharks extract oxygen from seawater as it passes over theirgills.Unlike other fish, shark gill slits are not covered, but lie in a row behind the head. A modified slit called aspiraclelies just behind the eye, which assists the shark with taking in water duringrespirationand plays a major role in bottom–dwelling sharks. Spiracles are reduced or missing in activepelagicsharks.[27]While the shark is moving, water passes through the mouth and over the gills in a process known as "ram ventilation". While at rest, most sharks pump water over their gills to ensure a constant supply of oxygenated water. A small number of species have lost the ability to pump water through their gills and must swim without rest. These species areobligate ram ventilatorsand would presumablyasphyxiateif unable to move. Obligate ram ventilation is also true of some pelagic bony fish species.[40][41]

Therespiratoryandcirculatoryprocess begins when deoxygenatedvenous bloodtravels to the shark's two-chamberedheart.Here, the shark pumps blood to its gills via the ventralaortawhere it branches intoafferentbranchial arteries.Gas exchangetakes place in the gills and the reoxygenated blood flows into theefferentbranchial arteries, which come together to form thedorsal aorta.The blood flows from the dorsal aorta throughout the body. The deoxygenated blood from the body then flows through theposterior cardinal veinsand enters the posterior cardinalsinuses.From there venous blood re-enters the heartventricleand the cycle repeats.[42]

Thermoregulation

Most sharks are "cold-blooded" or, more precisely,poikilothermic,meaning that their internalbody temperaturematches that of their ambient environment. Members of the familyLamnidae(such as theshortfin mako sharkand thegreat white shark) arehomeothermicand maintain a higher body temperature than the surrounding water. In these sharks, a strip ofaerobicred muscle located near the center of the body generates the heat, which the body retains via acountercurrent exchangemechanism by a system ofblood vesselscalled therete mirabile( "miraculous net" ). Thecommon thresherandbigeye threshersharks have a similar mechanism for maintaining an elevated body temperature.[43]

Larger species, like the whale shark, are able to conserve their body heat through sheer size when they dive to colder depths, and thescalloped hammerheadclose its mouth and gills when they dives to depths of around 800 metres, holding its breath till it reach warmer waters again.[44]

Osmoregulation

In contrast to bony fish, with the exception of thecoelacanth,[45]the blood and other tissue of sharks andChondrichthyesis generallyisotonicto their marine environments because of the high concentration ofurea(up to 2.5%[46]) andtrimethylamineN-oxide (TMAO), allowing them to be inosmoticbalance with the seawater. This adaptation prevents most sharks from surviving in freshwater, and they are therefore confined tomarineenvironments. A few exceptions exist, such as thebull shark,which has developed a way to change itskidneyfunction to excrete large amounts of urea.[38]When a shark dies, the urea is broken down to ammonia by bacteria, causing the dead body to gradually smell strongly of ammonia.[47][48]

Research in 1930 byHomer W. Smithshowed that sharks' urine does not contain sufficient sodium to avoidhypernatremia,and it was postulated that there must be an additional mechanism for salt secretion. In 1960 it was discovered at theMount Desert Island Biological LaboratoryinSalsbury Cove, Mainethat sharks have a type ofsalt glandlocated at the end of the intestine, known as the "rectal gland", whose function is the secretion of chlorides.[49]

Digestion

Digestion can take a long time. The food moves from the mouth to a J-shaped stomach, where it is stored and initial digestion occurs.[50]Unwanted items may never get past the stomach, and instead the shark either vomits or turns its stomachs inside out and ejects unwanted items from its mouth.[51]

One of the biggest differences between the digestive systems of sharks and mammals is that sharks have much shorter intestines. This short length is achieved by thespiral valvewith multiple turns within a single short section instead of a long tube-like intestine. The valve provides a long surface area, requiring food to circulate inside the short gut until fully digested, when remaining waste products pass into thecloaca.[50]

Fluorescence

A few sharks appearfluorescentunder blue light, such as theswell sharkand thechain catshark,where thefluorophorederives from ametaboliteofkynurenic acid.[52]

Senses

Smell

Sharks have keenolfactorysenses, located in the short duct (which is not fused, unlike bony fish) between the anterior and posterior nasal openings, with some species able to detect as little as onepart per millionof blood in seawater.[53]The size of the olfactory bulb varies across different shark species, with size dependent on how much a given species relies on smell or vision to find their prey.[54]In environments with low visibility, shark species generally have larger olfactory bulbs.[54]In reefs, where visibility is high, species of sharks from the familyCarcharhinidaehave smaller olfactory bulbs.[54]Sharks found in deeper waters also have larger olfactory bulbs.[55]

Sharks have the ability to determine the direction of a given scent based on the timing of scent detection in each nostril.[56]This is similar to the method mammals use to determine direction of sound.

They are more attracted to the chemicals found in the intestines of many species, and as a result often linger near or insewageoutfalls. Some species, such asnurse sharks,have externalbarbelsthat greatly increase their ability to sense prey.

Sight

Sharkeyesare similar to the eyes of othervertebrates,including similarlenses,corneasandretinas,though their eyesight is well adapted to themarineenvironment with the help of a tissue calledtapetum lucidum.This tissue is behind theretinaand reflects light back to it, thereby increasing visibility in the dark waters. The effectiveness of the tissue varies, with some sharks having strongernocturnaladaptations. Many sharks can contract and dilate theirpupils,like humans, something noteleost fishcan do. Sharks have eyelids, but they do not blink because the surrounding water cleans their eyes. To protect their eyes some species havenictitating membranes.This membrane covers the eyes while hunting and when the shark is being attacked. However, some species, including thegreat white shark(Carcharodon carcharias), do not have this membrane, but instead roll their eyes backwards to protect them when striking prey. The importance of sight in shark hunting behavior is debated. Some believe thatelectro-andchemoreceptionare more significant, while others point to the nictating membrane as evidence that sight is important, since presumably the shark would not protect its eyes were they unimportant. The use of sight probably varies with species and water conditions. The shark's field of vision can swap betweenmonocularandstereoscopicat any time.[57]Amicro-spectrophotometrystudy of 17 species of sharks found 10 had onlyrod photoreceptorsand no cone cells in theirretinasgiving them good night vision while making themcolorblind.The remaining seven species had in addition to rods a single type ofcone photoreceptorsensitive to green and, seeing only in shades of grey and green, are believed to be effectively colorblind. The study indicates that an object's contrast against the background, rather than colour, may be more important for object detection.[58] [59][60]

Hearing

Although it is hard to test the hearing of sharks, they may have a sharpsense of hearingand can possibly hear prey from many miles away.[61]The hearing sensitivity for most shark species lies between 20 and 1000 Hz.[62] A small opening on each side of their heads (not the spiracle) leads directly into theinner earthrough a thin channel. Thelateral lineshows a similar arrangement, and is open to the environment via a series of openings called lateral linepores.This is a reminder of the common origin of these two vibration- and sound-detecting organs that are grouped together as the acoustico-lateralis system. In bony fish andtetrapodsthe external opening into the inner ear has been lost.

Electroreception

Theampullae of Lorenziniare the electroreceptor organs. They number in the hundreds to thousands. Sharks use the ampullae of Lorenzini to detect theelectromagnetic fieldsthat all living things produce.[63]This helps sharks (particularly thehammerhead shark) find prey. The shark has the greatest electrical sensitivity of any animal. Sharks find prey hidden in sand by detecting theelectric fieldsthey produce.Ocean currentsmoving in themagnetic field of the Earthalso generate electric fields that sharks can use for orientation and possibly navigation.[64]

Lateral line

This system is found in most fish, including sharks. It is a tactile sensory system which allows the organism to detect water speed and pressure changes near by.[65]The main component of the system is the neuromast, a cell similar tohair cellspresent in the vertebrate ear that interact with the surrounding aquatic environment. This helps sharks distinguish between the currents around them, obstacles off on their periphery, and struggling prey out of visual view. The shark can sense frequencies in the range of 25 to 50Hz.[66]

Life history

Shark lifespans vary by species. Most live 20 to 30 years. Thespiny dogfishhas one of the longest lifespans at more than 100 years.[67]Whale sharks(Rhincodon typus) may also live over 100 years.[68]Earlier estimates suggested theGreenland shark(Somniosus microcephalus) could reach about 200 years, but a recent study found that a 5.02-metre-long (16.5 ft) specimen was 392 ± 120 years old (i.e., at least 272 years old), making it thelongest-livedvertebrate known.[69][70]

Reproduction

Unlike mostbony fish,sharks areK-selectedreproducers, meaning that they produce a small number of well-developed young as opposed to a large number of poorly developed young.Fecundityin sharks ranges from 2 to over 100 young per reproductive cycle.[71]Sharks mature slowly relative to many other fish. For example,lemon sharksreach sexual maturity at around age 13–15.[72]

Sexual

Sharks practiceinternal fertilization.[73]The posterior part of a male shark's pelvic fins are modified into a pair ofintromittent organscalledclaspers,analogous to amammalian penis,of which one is used to deliversperminto the female.[74]

Matinghas rarely been observed in sharks.[75]The smallercatsharksoften mate with the male curling around the female. In less flexible species the two sharks swim parallel to each other while the male inserts a clasper into the female'soviduct.Females in many of the larger species have bite marks that appear to be a result of a male grasping them to maintain position duringmating.The bite marks may also come from courtship behavior: the male may bite the female to show his interest. In some species, females have evolved thicker skin to withstand these bites.[74]

Asexual

There have been a number of documented cases in which a female shark who has not been in contact with a male has conceived a pup on her own throughparthenogenesis.[76][77]The details of this process are not well understood, butgenetic fingerprintingshowed that the pups had no paternal genetic contribution, ruling outsperm storage.The extent of this behavior in the wild is unknown. Mammals are now the only majorvertebrategroup in whichasexual reproductionhas not been observed.

Scientists say that asexual reproduction in the wild is rare, and probably a last-ditch effort to reproduce when a mate is not present. Asexual reproduction diminishesgenetic diversity,which helps build defenses against threats to the species. Species that rely solely on it risk extinction. Asexual reproduction may have contributed to theblue shark's decline off theIrishcoast.[78]

Brooding

Sharks display three ways to bear their young, varying by species,oviparity,viviparityandovoviviparity.[79][80]

Ovoviviparity

Most sharks areovoviviparous,meaning that the eggs hatch in theoviductwithin the mother's body and that the egg'syolkand fluids secreted by glands in the walls of the oviduct nourishes the embryos. The young continue to be nourished by the remnants of the yolk and the oviduct's fluids. As in viviparity, the young are born alive and fully functional.Lamniformesharks practiceoophagy,where the first embryos to hatch eat the remaining eggs. Taking this a step further,sand tiger sharkpups cannibalistically consume neighboring embryos. The survival strategy for ovoviviparous species is tobroodthe young to a comparatively large size before birth. Thewhale sharkis now classified as ovoviviparous rather than oviparous, because extrauterine eggs are now thought to have been aborted. Most ovoviviparous sharks give birth in sheltered areas, including bays, river mouths and shallow reefs. They choose such areas for protection from predators (mainly other sharks) and the abundance of food.Dogfishhave the longest knowngestation periodof any shark, at 18 to 24 months.Basking sharksandfrilled sharksappear to have even longer gestation periods, but accurate data are lacking.[79]

Oviparity

Some species areoviparous,laying their fertilized eggs in the water. In most oviparous shark species, anegg casewith the consistency ofleatherprotects the developing embryo(s). These cases may be corkscrewed into crevices for protection. The egg case is commonly called amermaid's purse.Oviparous sharks include thehorn shark,catshark,Port Jackson shark,andswellshark.[79][81]

Viviparity

Viviparity is the gestation of young without the use of a traditional egg, and results in live birth.[82]Viviparity in sharks can be placental or aplacental.[82]Young are born fully formed and self-sufficient.[82]Hammerheads, therequiem sharks(such as thebullandblue sharks), andsmoothhoundsare viviparous.[71][79]

Behavior

The classic view describes a solitary hunter, ranging the oceans in search of food. However, this applies to only a few species. Most live far more social, sedentary,benthiclives, and appear likely to have their own distinct personalities.[83]Even solitary sharks meet for breeding or at rich hunting grounds, which may lead them to cover thousands of miles in a year.[84]Shark migration patterns may be even more complex than in birds, with many sharks covering entireocean basins.

Sharks can be highly social, remaining in large schools. Sometimes more than 100scalloped hammerheadscongregate aroundseamountsand islands, e.g., in theGulf of California.[38]Cross-species social hierarchies exist. For example,oceanic whitetip sharksdominatesilky sharksof comparable size during feeding.[71]

When approached too closely some sharks perform athreat display.This usually consists of exaggerated swimming movements, and can vary in intensity according to the threat level.[85]

Speed

In general, sharks swim ( "cruise" ) at an average speed of 8 kilometres per hour (5.0 mph), but when feeding or attacking, the average shark can reach speeds upwards of 19 kilometres per hour (12 mph). Theshortfin mako shark,the fastest shark and one of the fastest fish, can burst at speeds up to 50 kilometres per hour (31 mph).[86]Thegreat white sharkis also capable of speed bursts. These exceptions may be due to thewarm-blooded,orhomeothermic,nature of these sharks' physiology. Sharks can travel 70 to 80 km in a day.[87]

Intelligence

Sharks possess brain-to-body mass ratios that are similar to mammals and birds,[88]and have exhibited apparent curiosity and behavior resembling play in the wild.[89][90]

There is evidence that juvenile lemon sharks can use observational learning in their investigation of novel objects in their environment.[91]

Sleep

All sharks need to keep water flowing over their gills in order for them to breathe; however, not all species need to be moving to do this. Those that are able to breathe while not swimming do so by using their spiracles to force water over their gills, thereby allowing them to extract oxygen from the water. It has been recorded that their eyes remain open while in this state and actively follow the movements of divers swimming around them[92]and as such they are not truly asleep.

Species that do need to swim continuously to breathe go through a process known as sleep swimming, in which the shark is essentially unconscious. It is known from experiments conducted on thespiny dogfishthat itsspinal cord,rather than its brain, coordinates swimming, sospiny dogfishcan continue to swim while sleeping, and this also may be the case in larger shark species.[92]In 2016 agreat white sharkwas captured on video for the first time in a state researchers believed was sleep swimming.[93]

Ecology

Feeding

Most sharks arecarnivorous.[94]Basking sharks,whale sharks,andmegamouth sharkshave independently evolved different strategies for filter feedingplankton:basking sharks practiceram feeding,whale sharks use suction to take in plankton and small fishes, and megamouth sharks makesuction feedingmore efficient by using theluminescenttissue inside of their mouths to attract prey in the deep ocean. This type of feeding requiresgill rakers—long, slender filaments that form a very efficientsieve—analogous to thebaleenplates of thegreat whales.The shark traps the plankton in these filaments and swallows from time to time in huge mouthfuls. Teeth in these species are comparatively small because they are not needed for feeding.[94]

Other highly specialized feeders includecookiecutter sharks,which feed on flesh sliced out of other larger fish andmarine mammals.Cookiecutter teeth are enormous compared to the animal's size. The lower teeth are particularly sharp. Although they have never been observed feeding, they are believed to latch onto their prey and use their thick lips to make a seal, twisting their bodies to rip off flesh.[38]

Some seabed–dwelling species are highly effective ambush predators.Angel sharksandwobbegongsuse camouflage to lie in wait and suck prey into their mouths.[95]Manybenthicsharks feed solely oncrustaceanswhich they crush with their flatmolariformteeth.

Other sharks feed onsquidor fish, which they swallow whole. Theviper dogfishhas teeth it can point outwards to strike and capture prey that it then swallows intact. Thegreat whiteand other large predators either swallow small prey whole or take huge bites out of large animals.Thresher sharksuse their long tails to stun shoaling fishes, andsawsharkseither stir prey from the seabed or slash at swimming prey with their tooth-studdedrostra.

Thebonnetheadshark is the only known omnivorous species. Its main prey is crustaceans and mollusks, but it also eats a large amount of seagrass, and is able to digest and extract nutrients from about 50% of the seagrass it consume.[96]

Many sharks, including thewhitetip reef sharkare cooperative feeders and hunt in packs to herd and capture elusive prey. These social sharks are often migratory, traveling huge distances aroundocean basinsin large schools. These migrations may be partly necessary to find new food sources.[97]

Range and habitat

Sharks are found in all seas. They generally do not live in fresh water, with a few exceptions such as thebull sharkand theriver sharkwhich can swim both in seawater and freshwater.[98]Sharks are common down to depths of 2,000 metres (7,000 ft), and some live even deeper, but they are almost entirely absent below 3,000 metres (10,000 ft). The deepest confirmed report of a shark is aPortuguese dogfishat 3,700 metres (12,100 ft).[99]

Relationship with humans

Attacks

In 2006 theInternational Shark Attack File(ISAF) undertook an investigation into 96 alleged shark attacks, confirming 62 of them as unprovoked attacks and 16 as provoked attacks. The average number of fatalities worldwide per year between 2001 and 2006 from unprovoked shark attacks is 4.3.[100]

Contrary to popular belief, only a few sharks are dangerous to humans. Out of more than 470 species, only four have been involved in a significant number of fatal, unprovoked attacks on humans: thegreat white,oceanic whitetip,tiger,andbull sharks.[101][102]These sharks are large, powerful predators, and may sometimes attack and kill people. Despite being responsible for attacks on humans they have all been filmed without using a protective cage.[103]

The perception of sharks as dangerous animals has been popularized by publicity given to a few isolated unprovoked attacks, such as theJersey Shore shark attacks of 1916,and through popular fictional works about shark attacks, such as theJawsfilm series.JawsauthorPeter Benchley,as well asJawsdirectorSteven Spielberg,later attempted to dispel the image of sharks as man-eating monsters.[104]

To help avoid an unprovoked attack, humans should not wear jewelry or metal that is shiny and refrain from splashing around too much.[105]

In general, sharks show little pattern of attacking humans specifically, part of the reason could be that sharks prefer the blood of fish and other common preys.[106]Research indicates that when humans do become the object of a shark attack, it is possible that the shark has mistaken the human for species that are its normal prey, such as seals.[107][108]This was further proven in a recent study conducted by researchers at the California State University's Shark Lab. According to footage caught by the Lab's drones, juveniles swam right up to humans in the water without any bites incidents. The lab stated that the results showed that humans and sharks can co-exist in the water.[109]

In captivity

Until recently, only a fewbenthicspecies of shark, such ashornsharks,leopard sharksandcatsharks,had survived in aquarium conditions for a year or more. This gave rise to the belief that sharks, as well as being difficult to capture and transport, were difficult to care for. More knowledge has led to more species (including the largepelagicsharks) living far longer in captivity, along with safer transportation techniques that have enabled long-distance transportation.[110]The great white shark had never been successfully held in captivity for long periods of time until September 2004, when theMonterey Bay Aquariumsuccessfully kept a young female for 198 days before releasing her.

Most species are not suitable for home aquaria, and not every species sold bypet storesare appropriate. Some species can flourish in home saltwater aquaria.[111]Uninformed or unscrupulous dealers sometimes sell juvenile sharks like thenurse shark,which upon reaching adulthood is far too large for typical home aquaria.[111]Public aquaria generally do not accept donated specimens that have outgrown their housing. Some owners have been tempted toreleasethem.[111]Species appropriate to home aquaria represent considerable spatial and financial investments as they generally approach adult lengths of 3 feet (90 cm) and can live up to 25 years.[111]

In culture

In Hawaii

Sharks figure prominently inHawaiian mythology.Stories tell of men with shark jaws on their back who could change between shark and human form. A common theme was that a shark-man would warn beach-goers of sharks in the waters. The beach-goers would laugh and ignore the warnings and get eaten by the shark-man who warned them.Hawaiianmythology also includes many sharkgods.Among a fishing people, the most popular of allaumakua,or deified ancestor guardians, are shark aumakua.Kamakudescribes in detail how to offer a corpse to become a shark. The body transforms gradually until thekahunacan point the awe-struck family to the markings on the shark's body that correspond to the clothing in which the beloved's body had been wrapped. Such a shark aumakua becomes the family pet, receiving food, and driving fish into the family net and warding off danger. Like all aumakua it had evil uses such as helping kill enemies. The ruling chiefs typically forbade such sorcery. Many Native Hawaiian families claim such an aumakua, who is known by name to the whole community.[112]

Kamohoali'iis the best known and revered of the shark gods, he was the older and favored brother ofPele,[113]and helped and journeyed with her to Hawaii. He was able to assume all human and fish forms. A summit cliff on the crater ofKilaueais one of his most sacred spots. At one point he had aheiau(temple or shrine) dedicated to him on every piece of land that jutted into the ocean on the island ofMolokai.Kamohoali'i was an ancestral god, not a human who became a shark and banned the eating of humans after eating one herself.[114][115]In Fi gian mythology,Dakuwaqawas a shark god who was the eater of lost souls.

In American Samoa

On the island ofTutuilainAmerican Samoa(aU.S. territory), there is a location calledTurtle and Shark(Laumei ma Malie) which is important inSamoan culture—the location is the site of a legend calledO Le Tala I Le Laumei Ma Le Malie,in which two humans are said to have transformed into a turtle and a shark.[116][117][118]According to theU.S. National Park Service,"Villagers from nearbyVaitogicontinue to reenact an important aspect of the legend at Turtle and Shark by performing a ritual song intended to summon the legendary animals to the ocean surface, and visitors are frequently amazed to see one or both of these creatures emerge from the sea in apparent response to this call. "[116]

In popular culture

In contrast to the complex portrayals by Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, the European and Western view of sharks has historically been mostly of fear and malevolence.[119]Sharks are used in popular culture commonly as eating machines, notably in theJawsnovel and thefilm of the same name,along with itssequels.[120]Sharks are threats in other films such asDeep Blue Sea,The Reef,andothers,although they are sometimes used for comedic effect such as inFinding Nemoand theAustin Powersseries. Sharks tend to be seen quite often in cartoons whenever a scene involves the ocean. Such examples include theTom and Jerrycartoons,Jabberjaw,and other shows produced by Hanna-Barbera. They also are used commonly as a clichéd means of killing off a character that is held up by a rope or some similar object as the sharks swim right below them, or the character may be standing on aplankabove shark infested waters.[citation needed]

Popular misconceptions

A popular myth is that sharks are immune to disease andcancer,but this is not scientifically supported. Sharks have been known to get cancer.[121][122]Both diseases andparasitesaffect sharks. The evidence that sharks are at least resistant to cancer and disease is mostlyanecdotaland there have been few, if any, scientific orstatisticalstudies that show sharks to have heightened immunity to disease.[123] Other apparently false claims are that fins preventcancer[124]and treatosteoarthritis.[125]No scientific proof supports these claims; at least one study has shown shark cartilage of no value in cancer treatment.[126]

Threats to sharks

Fishery

In 2008, it was estimated that nearly 100 million sharks were being killed by people every year, due to commercial and recreational fishing.[127][128]In 2021, it was estimated that the population of oceanic sharks and rays had dropped by 71% over the previous half-century.[6]

Shark finning yields are estimated at 1.44 million metric tons (1.59 million short tons) for 2000, and 1.41 million metric tons (1.55 million short tons) for 2010. Based on an analysis of average shark weights, this translates into a total annual mortality estimate of about 100 million sharks in 2000, and about 97 million sharks in 2010, with a total range of possible values between 63 and 273 million sharks per year.[129][130]Sharks are a common seafood in many places, includingJapanandAustralia.In southern Australia, shark is commonly used infish and chips,[131]in which fillets are battered anddeep-friedor crumbed and grilled. In fish and chip shops, shark is calledflake.InIndia,small sharks or baby sharks (called sora inTamil language,Telugu language) are sold in local markets. Since the flesh is not developed, cooking the flesh breaks it into powder, which is then fried in oil and spices (called sora puttu/sora poratu). The soft bones can be easily chewed. They are considered a delicacy in coastalTamil Nadu.IcelandersfermentGreenland sharksto produce a delicacy calledhákarl.[132]During a four-year period from 1996 to 2000, an estimated 26 to 73 million sharks were killed and traded annually in commercial markets.[133]

Sharks are often killed forshark fin soup.Fishermen capture live sharks, fin them, and dump the finless animal back into the water.Shark finninginvolves removing the fin with a hot metal blade.[128]The resulting immobile shark soon dies from suffocation or predators.[134]Shark fin has become a major trade within black markets all over the world. Fins sell for about $300/lb in 2009.[135]Poachers illegally fin millions each year. Few governments enforce laws that protect them.[130]In 2010 Hawaii became the first U.S. state to prohibit the possession, sale, trade or distribution of shark fins.[136]From 1996 to 2000, an estimated 38 million sharks had been killed per year for harvesting shark fins.[133]It is estimated byTRAFFICthat over 14,000 tonnes of shark fins were exported into Singapore between 2005–2007 and 2012–2014.[137]

Shark fin soup is astatus symbolin Asian countries and is erroneously considered healthy and full of nutrients. Scientific research has revealed, however, that high concentrations ofBMAAare present in shark fins.[138]Because BMAA is aneurotoxin,consumption ofshark fin soupand cartilage pills, therefore, may pose a health risk.[139]BMAA is under study for its pathological role in neurodegegerative diseases such asALS,Alzheimer's disease,andParkinson's disease.

Sharks are also killed formeat.European diners consumedogfishes,smoothhounds,catsharks,makos, porbeagle and also skates and rays.[140]However, theU.S.FDAlists sharks as one of four fish (withswordfish,king mackerel,andtilefish) whose highmercury contentis hazardous to children and pregnant women.

Sharks generally reachsexual maturityonly after many years and produce few offspring in comparison to other harvested fish. Harvesting sharks before they reproduce severely impacts future populations. Capture induced premature birth and abortion (collectively called capture-induced parturition) occurs frequently in sharks/rays when fished.[73]Capture-induced parturition is rarely considered in fisheries management despite being shown to occur in at least 12% of live bearing sharks and rays (88 species to date).[73]

The majority of shark fisheries have little monitoring or management. The rise in demand for shark products increases pressure on fisheries.[39]Major declines in shark stocks have been recorded—some species have been depleted by over 90% over the past 20–30 years with population declines of 70% not unusual.[141]A study by theInternational Union for Conservation of Naturesuggests that one quarter of all known species of sharks and rays are threatened by extinction and 25 species were classified as critically endangered.[142][143]

Shark culling

In 2014, ashark cull in Western Australiakilled dozens of sharks (mostlytiger sharks) usingdrum lines,[144]until it was cancelled after public protests and a decision by the Western Australia EPA; from 2014 to 2017, there was an "imminent threat" policy in Western Australia in which sharks that "threatened" humans in the ocean were shot and killed.[145]This "imminent threat" policy was criticized by senator Rachel Siewart for killing endangered sharks.[146]The "imminent threat" policy was cancelled in March 2017.[147]In August 2018, the Western Australia government announced a plan to re-introduce drum lines (though, this time the drum lines are "SMART" drum lines).[148]

From 1962 to the present,[149]the government ofQueenslandhas targeted and killed sharks in large numbers by usingdrum lines,under a "shark control" program—this program has also inadvertently killed large numbers of other animals such asdolphins;it has also killed endangeredhammerhead sharks.[150][151][152][153]Queensland's drum line program has been called "outdated, cruel and ineffective".[153]From 2001 to 2018, a total of 10,480 sharks were killed on lethal drum lines in Queensland, including in theGreat Barrier Reef.[154]From 1962 to 2018, roughly 50,000 sharks were killed by Queensland authorities.[155]

The government ofNew South Waleshas a program that deliberately kills sharks usingnets.[152][156]The current net program in New South Wales has been described as being "extremely destructive" to marine life, including sharks.[157]Between 1950 and 2008, 352tiger sharksand 577great white sharkswere killed in the nets in New South Wales—also during this period, a total of 15,135 marine animals were killed in the nets, including dolphins, whales, turtles, dugongs, and critically endangeredgrey nurse sharks.[158]There has been a very large decrease in the number of sharks in eastern Australia, and the shark-killing programs in Queensland and New South Wales are partly responsible for this decrease.[155]

Kwazulu-Natal,an area ofSouth Africa,has a shark-killing program using nets and drum lines—these nets and drum lines have killed turtles and dolphins, and have been criticized for killing wildlife.[159]During a 30-year period, more than 33,000 sharks have been killed in KwaZulu-Natal's shark-killing program—during the same 30-year period, 2,211 turtles, 8,448 rays, and 2,310 dolphins were killed in KwaZulu-Natal.[159]Authorities on the French island ofRéunionkill about 100 sharks per year.[160]

Killing sharks negatively affects the marine ecosystem.[161][162]Jessica Morris ofHumane Society Internationalcalls shark culling a "knee-jerk reaction" and says, "sharks are top order predators that play an important role in the functioning of marine ecosystems. We need them for healthy oceans."[163]

George H. Burgess,the former[164]director of theInternational Shark Attack File,"describes [shark] culling as a form of revenge, satisfying a public demand for blood and little else";[165]he also said shark culling is a "retro-type move reminiscent of what people would have done in the 1940s and 50s, back when we didn't have an ecological conscience and before we knew the consequences of our actions."[165]Jane Williamson, an associate professor in marine ecology at Macquarie University, says "There is no scientific support for the concept that culling sharks in a particular area will lead to a decrease in shark attacks and increase ocean safety."[166]

Other threats

Other threats include habitat alteration, damage and loss from coastal development, pollution and the impact of fisheries on the seabed and prey species.[167]The 2007 documentarySharkwaterexposed how sharks are being hunted to extinction.[168]

Conservation

In 1991,South Africawas the first country in the world to declare Great White sharks a legally protected species[169](however, theKwaZulu-Natal Sharks Boardis allowed to kill great white sharks in its "shark control"program in eastern South Africa).[159]

Intending to ban the practice of shark finning while at sea, the United States Congress passed theShark Finning Prohibition Actin 2000.[170]Two years later the Act saw its first legal challenge inUnited States v. Approximately 64,695 Pounds of Shark Fins.In 2008 aFederal Appeals Courtruled that aloopholein the law allowed non-fishing vessels topurchaseshark fins fromfishing vesselswhile on the high seas.[171]Seeking to close the loophole, theShark Conservation Actwas passed by Congress in December 2010, and it was signed into law in January 2011.[172][173]

In 2003, the European Union introduced a general shark finning ban for all vessels of all nationalities in Union waters and for all vessels flying a flag of one of its member states.[174]This prohibition was amended in June 2013 to close remaining loopholes.[175]

In 2009, theInternational Union for Conservation of Nature'sIUCN Red Listof Endangered Speciesnamed 64 species, one-third of all oceanic shark species, as being at risk of extinction due to fishing and shark finning.[176][177]

In 2010, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) rejected proposals from theUnited StatesandPalauthat would have required countries to strictly regulate trade in several species ofscalloped hammerhead,oceanic whitetipandspiny dogfish sharks.The majority, but not the required two-thirds of voting delegates, approved the proposal.China,by far the world's largest shark market, andJapan,which battles all attempts to extend the convention to marine species, led the opposition.[178][179]In March 2013, three endangered commercially valuable sharks, thehammerheads,the oceanic whitetip andporbeaglewere added to Appendix 2 ofCITES,bringing shark fishing and commerce of these species under licensing and regulation.[180]

In 2010, Greenpeace International added theschool shark,shortfin mako shark,mackerel shark,tiger sharkandspiny dogfishto its seafood red list, a list of commonsupermarketfish that are often sourced from unsustainable fisheries.[181]Advocacy groupShark Trustcampaigns to limit shark fishing. Advocacy groupSeafood Watchdirects American consumers to not eat sharks.[182]

Under the auspices of theConvention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals(CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, theMemorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharkswas concluded and came into effect in March 2010. It was the first global instrument concluded under CMS and aims at facilitating international coordination for the protection, conservation and management of migratory sharks, through multilateral, intergovernmental discussion and scientific research.

In July 2013, New York state, a major market and entry point for shark fins, banned the shark fin trade joining seven other states of the United States and the three Pacific U.S. territories in providing legal protection to sharks.[183]

In theUnited States,and as of January 16, 2019, 12 states including (Massachusetts,Maryland,Delaware,California,Illinois,Hawaii,Oregon,Nevada,Rhode Island,Washington,New YorkandTexas) along with 3U.S. territories(American Samoa,Guamand theNorthern Mariana Islands) have passed laws against the sale or possession of shark fins.[184][185]

Several regions now haveshark sanctuariesor have banned shark fishing—these regions includeAmerican Samoa,theBahamas,theCook Islands,French Polynesia,Guam,theMaldives,theMarshall Islands,Micronesia,theNorthern Mariana Islands,andPalau.[186][187][188]

In April 2020 researchers reported to have traced the origins ofshark finsof endangeredhammerhead sharksfrom a retail market in Hong Kong back to their source populations and therefore the approximate locations where the sharks were first caught usingDNA analysis.[189][190]

In July 2020 scientists reported results of a survey of 371 reefs in 58 nations estimating theconservation status of reef sharks globally.No sharks have been observed on almost 20% of the surveyed reefs and shark depletion was strongly associated with both socio-economic conditions and conservation measures.[191][192]Sharks are considered to be a vital part of the oceanecosystem.

According to a 2021 study inNature,[193]overfishinghas resulted in a 71% global decline in the number of oceanic sharks andraysover the preceding 50 years. The oceanic whitetip, and both the scalloped hammerhead andgreat hammerheadsare now classified ascritically endangered.[194]Sharks intropical watershave declined more rapidly than those intemperate zonesduring the period studied.[195]A 2021 study published inCurrent Biologyfound that overfishing is currently driving over one-third of sharks and rays toextinction.[196]

See also

References

Citations

- ^Andreev, Plamen; Coates, Michael I.; Karatajūtė-Talimaa, Valentina; Shelton, Richard M.; Cooper, Paul R.; Wang, Nian-Zhong; Sansom, Ivan J. (2016-06-16)."The systematics of the Mongolepidida (Chondrichthyes) and the Ordovician origins of the clade".PeerJ.4:e1850.doi:10.7717/peerj.1850.ISSN2167-8359.PMC4918221.PMID27350896.S2CID9236223.

- ^Marjanović, D. (2021)."The Making of Calibration Sausage Exemplified by Recalibrating the Transcriptomic Timetree of Jawed Vertebrates".Frontiers in Genetics.12.521693.doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.521693.PMC8149952.PMID34054911.

- ^Pimiento, Catalina; Cantalapiedra, Juan L.; Shimada, Kenshu; Field, Daniel J.; Smaers, Jeroen B. (24 January 2019)."Evolutionary pathways toward gigantism in sharks and rays".Evolution.73(2): 588–599.doi:10.1111/evo.13680.PMID30675721.S2CID59224442.

- ^Allen, Thomas B. (1999).The Shark Almanac.New York: The Lyons Press.ISBN978-1-55821-582-5.OCLC39627633.

- ^Budker, Paul (1971).The Life of Sharks.London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.ISBN9780231035514.

- ^abEinhorn, Catrin (January 27, 2021)."Shark Populations Are Crashing, with a 'Very Small Window' to Avert Disaster".The New York Times.RetrievedJanuary 31,2021.

- ^"Online Etymology Dictionary".Etymonline.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-10-04.Retrieved2013-09-07.

- ^Marx, Robert F. (1990).The History of Underwater Exploration.Courier Dover Publications. p.3.ISBN978-0-486-26487-5.

- ^Online Etymology Dictionary, shark.

- ^Jones, Tom."The Xoc, the Sharke, and the Sea Dogs: An Historical Encounter".Archivedfrom the original on 2008-11-21.Retrieved2009-07-11.

- ^"Shark".Middle English Dictionary.University of Michigan.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-08-20.Retrieved2014-02-02.

- ^Andreev, Plamen S.; Sansom, Ivan J.; Li, Qiang; Zhao, Wenjin; Wang, Jianhua; Wang, Chun-Chieh; Peng, Li gian; Jia, Liantao; Qiao, Tuo; Zhu, Min (September 2022)."Spiny chondrichthyan from the lower Silurian of South China".Nature.609(7929): 969–974.Bibcode:2022Natur.609..969A.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05233-8.PMID36171377.S2CID252570103.

- ^Frey, Linda; Coates, Michael; Ginter, Michał; Hairapetian, Vachik; Rücklin, Martin; Jerjen, Iwan; Klug, Christian (2019-10-09)."The early elasmobranch Phoebodus: phylogenetic relationships, ecomorphology and a new time-scale for shark evolution".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.286(1912): 20191336.doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1336.ISSN0962-8452.PMC6790773.PMID31575362.

- ^Ginter, Michał (July 2022)."The biostratigraphy of Carboniferous chondrichthyans".Geological Society, London, Special Publications.512(1): 769–790.Bibcode:2022GSLSP.512..769G.doi:10.1144/SP512-2020-91.ISSN0305-8719.S2CID229399689.

- ^Pough, F. Harvey; Janis, Christine M. (2018).Vertebrate Life, 10th Edition.Oxford University Press. pp. 96–103.ISBN9781605357218.

- ^Andreev, Plamen S.; Cuny, Gilles (2012-02-28)."New Triassic stem selachimorphs (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) and their bearing on the evolution of dental enameloid in Neoselachii".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.32(2): 255–266.Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..255A.doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.644646.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID84162775.

- ^Underwood, Charlie J. (March 2006)."Diversification of the Neoselachii (Chondrichthyes) during the Jurassic and Cretaceous".Paleobiology.32(2): 215–235.Bibcode:2006Pbio...32..215U.doi:10.1666/04069.1.ISSN0094-8373.S2CID86232401.

- ^Rees, J. A. N., and Underwood, C. J., 2008, Hybodont sharks of the English Bathonian and Callovian (Middle Jurassic): Palaeontology, v. 51, no. 1, p. 117–147.

- ^Amaral, Cesar; Pereira, Filipe; Silva, Dayse; Amorim, António; de Carvalho, Elizeu F (2017)."The mitogenomic phylogeny of the Elasmobranchii (Chondrichthyes)".Mitochondrial DNA Part A.29(6): 1–12.doi:10.1080/24701394.2017.1376052.PMID28927318.S2CID3258973.

- ^ab"Sharks (Chondrichthyes)".FAO.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-08-02.Retrieved2009-09-14.

- ^Pavan-Kumar, A.; Gireesh-Babu, P.; Babu, P. P. Suresh; Jaiswar, A. K.; Hari Krishna, V.; Prasasd, K. Pani; Chaudhari, Aparna; Raje, S. G.; Chakraborty, S. K. (January 2014). "Molecular phylogeny of elasmobranchs inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear markers".Molecular Biology Reports.41(1): 447–457.doi:10.1007/s11033-013-2879-6.PMID24293104.S2CID16018112.

- ^Amaral, Cesar R. L.; Pereira, Filipe; Silva, Dayse A.; Amorim, António; de Carvalho, Elizeu F. (2017-09-20)."The mitogenomic phylogeny of the Elasmobranchii (Chondrichthyes)".Mitochondrial DNA Part A.29(6): 867–878.doi:10.1080/24701394.2017.1376052.PMID28927318.S2CID3258973.

- ^ab"Compagno's FAO Species List - 1984".Elasmo. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-05-28.Retrieved2009-09-14.

- ^ab"Echinorhiniformes".WoRMS.Retrieved2022-01-29.

- ^Straube, Nicolas; Li, Chenhong; Claes, Julien M.; Corrigan, Shannon; Naylor, Gavin J. P. (2015)."Molecular phylogeny of Squaliformes and first occurrence of bioluminescence in sharks".BMC Evolutionary Biology.15(1): 162.Bibcode:2015BMCEE..15..162S.doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0446-6.ISSN1471-2148.PMC4537554.PMID26277575.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Teeth of the Skin".Archivedfrom the original on 2007-10-12.Retrieved2007-08-28.

- ^abGilbertson, Lance (1999).Zoology Laboratory Manual.New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.ISBN978-0-07-237716-3.

- ^abMartin, R. Aidan."Skeleton in the Corset".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-11-25.Retrieved2009-08-21.

- ^ab"A Shark's Skeleton & Organs".Archived fromthe originalon August 5, 2010.RetrievedAugust 14,2009.

- ^Hamlett, W. C. (1999f).Sharks, Skates and Rays: The Biology of Elasmobranch Fishes.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-6048-5.OCLC39217534.

- ^Hamlett, William C. (April 23, 1999).Sharks, skates, and rays: the biology of elasmobranch fishes(1st ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 56.ISBN978-0-8018-6048-5.

- ^abMartin, R. Aidan."The Importance of Being Cartilaginous".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-02-27.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Skin of the Teeth".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-08-01.Retrieved2007-08-28.

- ^"Camouflage facts".National Geographic Society.4 January 2019. Archived fromthe originalon March 1, 2021.Retrieved2021-11-25.

- ^Womersley, Freya; Hancock, James; Perry, Cameron T.; Rowat, David (February 2021)."Wound-healing capabilities of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) and implications for conservation management".Conservation Physiology.9(1): coaa120.doi:10.1093/conphys/coaa120.PMC7859907.PMID33569175.

- ^Michael, Bright."Jaws: The Natural History of Sharks".Columbia University. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-05-11.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^Nelson, Joseph S. (1994).Fishes of the World.New York: John Wiley and Sons.ISBN978-0-471-54713-6.OCLC28965588.

- ^abcdCompagno, Leonard; Dando, Marc; Fowler, Sarah (2005).Sharks of the World.Collins Field Guides.ISBN978-0-00-713610-0.OCLC183136093.

- ^abPratt, H. L. Jr; Gruber, S. H.; Taniuchi, T (1990).Elasmobranchs as living resources: Advances in the biology, ecology, systematics, and the status of the fisheries.NOAA Tech Rept.

- ^Bennetta, William J. (1996)."Deep Breathing".Archived fromthe originalon 2007-08-14.Retrieved2007-08-28.

- ^"Do sharks sleep".Flmnh.ufl.edu. 2017-05-02. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-09-18.

- ^"SHARKS & RAYS, SeaWorld/Busch Gardens ANIMALS, CIRCULATORY SYSTEM".Busch Entertainment Corporation. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-04-24.Retrieved2009-09-03.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan (April 1992)."Fire in the Belly of the Beast".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-09-17.Retrieved2009-08-21.

- ^Nogrady, Bianca (May 11, 2023)."Hammerhead sharks are first fish found to 'hold their breath'".Nature.617(7962): 663.Bibcode:2023Natur.617..663N.doi:10.1038/d41586-023-01569-x.PMID37169849.S2CID258639015– via nature.

- ^Griffith, R. W (1980). "Chemistry of the Body Fluids of the Coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.208(1172): 329–347.Bibcode:1980RSPSB.208..329G.doi:10.1098/rspb.1980.0054.JSTOR35431.PMID6106196.S2CID38498079.

- ^"Sharkproject".Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved31 December2016.

- ^Musick, John A. (2005)."Management techniques for elasmobranch fisheries: 14. Shark Utilization".FAO: Fisheries and Aquaculture Department.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-07-22.Retrieved2008-03-16.

- ^Batten, Thomas."MAKO SHARK Isurus oxyrinchus".Delaware Sea Grant, University of Delaware. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-03-11.Retrieved2008-03-16.

- ^Forrest, John N. (Jnr.) (2016)."The Shark Rectal Gland Model: A Champion of Receptor Mediated Chloride Secretion Through CFTR".Transactions of the American Clinical Climatological Association.127:162–175.PMC5216465.PMID28066051.

- ^abMartin, R. Aidan."No Guts, No Glory".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-08-11.Retrieved2009-08-22.

- ^Potenza, Alessandra (20 June 2017)."Sharks literally puke their guts out—here's why".The Verge.Archivedfrom the original on 19 June 2017.Retrieved21 June2017.

- ^Park, Hyun Bong; Lam, Yick Chong; Gaffney, Jean P.; Weaver, James C.; Krivoshik, Sara Rose; Hamchand, Randy; Pieribone, Vincent; Gruber, David F.; Crawford, Jason M. (27 September 2019)."Bright Green Biofluorescence in Sharks Derives from Bromo-Kynurenine Metabolism".iScience.19:1291–1336.Bibcode:2019iSci...19.1291P.doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.07.019.PMC6831821.PMID31402257.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Smell and Taste".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-12-07.Retrieved2009-08-21.

- ^abcYopak, Kara E.; Lisney, Thomas J.; Collin, Shaun P. (2015-03-01)."Not all sharks are" swimming noses ": variation in olfactory bulb size in cartilaginous fishes".Brain Structure and Function.220(2): 1127–1143.doi:10.1007/s00429-014-0705-0.ISSN1863-2661.PMID24435575.S2CID2829434.

- ^Yopak, Kara E.; Lisney, Thomas J.; Darlington, Richard B.; Collin, Shaun P.; Montgomery, John C.; Finlay, Barbara L. (2010-07-20)."A conserved pattern of brain scaling from sharks to primates".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.107(29): 12946–12951.Bibcode:2010PNAS..10712946Y.doi:10.1073/pnas.1002195107.ISSN0027-8424.PMC2919912.PMID20616012.S2CID2151639.

- ^The Function of Bilateral Odor Arrival Time Differences in Olfactory Orientation of SharksArchived2012-03-08 at theWayback Machine,Jayne M. Gardiner, Jelle Atema, Current Biology - 13 July 2010 (Vol. 20, Issue 13, pp. 1187–1191)

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Vision and a Carpet of Light".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-04-29.Retrieved2009-08-22.

- ^"Sharks are colour-blind, new study finds".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-01-24.Retrieved2011-02-03.

- ^Gill, Victoria (2011-01-18)."Sharks are probably colour-blind".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-01-19.Retrieved2011-01-19.

- ^Nathan Scott Hart; Susan Michelle Theiss; Blake Kristin Harahush; Shaun Patrick Collin (2011). "Microspectrophotometric evidence for cone monochromacy in sharks".Naturwissenschaften.98(3): 193–201.Bibcode:2011NW.....98..193H.doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0758-8.PMID21212930.S2CID30148811.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Hearing and Vibration Detection".Archived fromthe originalon 2008-05-01.Retrieved2008-06-01.

- ^Casper, B. M. (2006).The hearing abilities of elasmobranch fishes(PhD dissertation). University of South Florida. p. 16.

- ^Kalmijn AJ (1982). "Electric and magnetic field detection in elasmobranch fishes".Science.218(4575): 916–8.Bibcode:1982Sci...218..916K.doi:10.1126/science.7134985.PMID7134985.

- ^Meyer CG; Holland KN; Papastamatiou YP (2005)."Sharks can detect changes in the geomagnetic field".Journal of the Royal Society, Interface.2(2): 129–30.doi:10.1098/rsif.2004.0021.PMC1578252.PMID16849172.

- ^Bleckmann, Horst; Zelick, Randy (March 2009)."Lateral line system of fish".Integrative Zoology.4(1): 13–25.doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2008.00131.x.ISSN1749-4877.PMID21392273.

- ^Popper, A. N.; C. Platt (1993). "Inner ear and lateral line".The Physiology of Fishes(1st ed).

- ^"Mote Marine Laboratory," Shark Notes "".Mote.org. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-01-24.Retrieved2012-08-27.

- ^"Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department," National Shark Research Consortium–Shark Basics "".Archived fromthe originalon September 4, 2007.

- ^Nielsen, J.; Hedeholm, R. B.; Heinemeier, J.; Bushnell, P. G.; Christiansen, J. S.; Olsen, J.; Ramsey, C. B.; Brill, R. W.; Simon, M.; Steffensen, K. F.; Steffensen, J. F. (2016-08-12)."Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) ".Science.353(6300): 702–704.Bibcode:2016Sci...353..702N.doi:10.1126/science.aaf1703.hdl:2022/26597.PMID27516602.S2CID206647043.

- ^Pennisi, Elizabeth (11 August 2016)."Greenland shark may live 400 years, smashing longevity record".Science.doi:10.1126/science.aag0748.Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2016.Retrieved11 August2016.

- ^abcLeonard J. V. Compagno (1984).Sharks of the World: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.ISBN978-92-5-104543-5.OCLC156157504.

- ^Gruber, Samuel H. (February 21, 2000)."LIFE STYLE OF SHARKS".Archived fromthe originalon July 27, 2011.RetrievedJune 20,2010.

- ^abcAdams, Kye R.; Fetterplace, Lachlan C.; Davis, Andrew R.; Taylor, Matthew D.; Knott, Nathan A. (January 2018)."Sharks, rays and abortion: The prevalence of capture-induced parturition in elasmobranchs".Biological Conservation.217:11–27.Bibcode:2018BCons.217...11A.doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.010.S2CID90834034.Archived fromthe originalon 2019-02-23.Retrieved2018-11-24.

- ^abMartin, R. Aidan."Why Do Sharks Have Two Penises?".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-08-28.Retrieved2009-08-22.

- ^"How Do Sharks Mate? - Center For Ocean Life".Center For Ocean Life.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-09-06.Retrieved2018-09-09.

- ^Chapman DD; Shivji MS; Louis E; Sommer J; Fletcher H; Prodöhl PA (2007)."Virgin birth in a hammerhead shark".Biology Letters.3(4): 425–7.doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0189.PMC2390672.PMID17519185.

- ^In shark tank, an asexual birthArchived2009-07-09 at theWayback Machine,Boston Globe, 10 Oct. 2008

- ^Fountain, Henry (2007-05-23)."Female sharks reproduce without male DNA, scientists say".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-04-17.Retrieved2007-11-13.

- ^abcd"SHARKS & RAYS, SeaWorld/Busch Gardens ANIMALS, BIRTH & CARE OF YOUNG".Busch Entertainment Corporation. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-08-03.Retrieved2009-09-03.

- ^Adams, Kye R; Fetterplace, Lachlan C; Davis, Andrew R; Taylor, Matthew D; Knott, Nathan A (2018)."Sharks, rays and abortion: The prevalence of capture-induced parturition in elasmobranchs".Biological Conservation.217:11–27.Bibcode:2018BCons.217...11A.doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.010.S2CID90834034.Archived fromthe originalon 2019-02-23.Retrieved2018-11-24.

- ^"Marine Biology notes".School of Life Sciences,Napier University.Archived fromthe originalon 2003-08-23.Retrieved2006-09-12.

- ^abcCarrier, J.C; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. (2012).Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives: Second Edition.Taylor & Francis Group.

- ^The truth about sharks: Far from being 'killing machines', they have personalities, best friends and an exceptional capacity for learningArchived2015-07-03 at theWayback Machine(2014-11-28),The Independent

- ^Ravilious, Kate (2005-10-07)."Scientists track shark's 12,000 mile round-trip".Guardian Unlimited.London.Retrieved2006-09-17.

- ^Johnson, Richard H. & Nelson, Donald R. (1973-03-05). "Agonistic Display in the Gray Reef Shark,Carcharhinus menisorrah,and Its Relationship to Attacks on Man ".Copeia.1973(1): 76–84.doi:10.2307/1442360.JSTOR1442360.

- ^Reefquest Center for Shark Research.What's the Speediest Marine Creature?Archived2009-04-14 at theWayback Machine

- ^The secret life of sharksArchived2012-04-05 at theWayback Machine,Maria Moscaritolo,The Adelaide Advertiser,3 March 2012.

- ^Ruckstuhl, Kathreen E.; Neuhaus, Peter, eds. (January 23, 2006). "Sexual Segregation in Sharks".Sexual segregation in vertebrates.Cambridge University Press. p. 128.ISBN978-0-521-83522-0.

- ^"Is the White Shark Intelligent".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-08-01.Retrieved2006-08-07.

- ^"Biology of the Porbeagle".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-07-29.Retrieved2006-08-07.

- ^Guttridge, T.L.; van Dijk, S.; Stamhuis, E.J.; Krause, J.; Gruber, S.H.; Brown, C. (2013)."Social learning in juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris".Animal Cognition.16(1): 55–64.doi:10.1007/s10071-012-0550-6.PMID22933179.S2CID351363.Archived fromthe originalon 2019-04-27.Retrieved2019-09-05.

- ^ab"How Do Sharks Swim When Asleep?".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-07-29.Retrieved2006-08-07.

- ^"Great White Shark Caught On Camera Napping For The First Time".NPR. 6 July 2016.Retrieved16 December2019.

- ^abMartin, R. Aidan."Building a Better Mouth Trap".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-07-10.Retrieved2009-08-22.

- ^Martin, R. Aidan."Order Orectolobiformes: Carpet Sharks—39 species".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-04-29.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^Seagrass digestion by a notorious 'carnivore' - Journals

- ^Stevens 1987

- ^"Carcharhinus leucas".University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-06-05.Retrieved2006-09-08.

- ^Priede IG, Froese R, Bailey DM, et al. (2006)."The absence of sharks from abyssal regions of the world's oceans".Proceedings: Biological Sciences.273(1592): 1435–41.doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3461.PMC1560292.PMID16777734.

- ^"Worldwide shark attack summary".International Shark Attack File.Archived fromthe originalon 2007-08-18.Retrieved2007-08-28.

- ^"Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark".ISAF. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-07-24.Retrieved2006-09-12.

- ^"Biology of sharks and rays".ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research.Archivedfrom the original on 2006-02-06.Retrieved2014-01-17.

- ^Buttigieg, Alex."The Sharkman meets Ron & Valerie Taylor".Sharkman's Graphics. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-03-03.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^Handwerk, Brian (7 June 2002)."Jaws Author Peter Benchley Talks Sharks".National Geographic Society. Archived fromthe originalon 25 August 2009.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^"How Should We Respond When Humans and Sharks Collide?".News.nationalgeographic. 2013-07-04. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-09-06.Retrieved2013-09-07.

- ^"Sharks and Survival: Three misconceptions about sharks; one striking reality".Loggerhead Marinelife Center. 2016-07-01.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-05-09.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^Gray, Richard (5 December 2023)."The real reasons why sharks attack humans".bbc.Retrieved2024-06-04.

- ^Chapman, Blake K.; McPhee, Daryl (2016)."Global shark attack hotspots: Identifying underlying factors behind increased unprovoked shark bite incidence".Ocean and Coastal Management.133:72.Bibcode:2016OCM...133...72C.doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.09.010.

- ^Dazio, Stefanie (June 7, 2023)."Just keep swimming: SoCal study shows sharks, humans can share ocean peacefully".AP News.RetrievedJune 8,2023.

- ^"Whale Sharks in Captivity".Archived fromthe originalon September 2, 2006.Retrieved2006-09-13.

- ^abcdMichael, Scott W. (March 2004). "Sharks at Home".Aquarium Fish Magazine.pp. 20–29.

- ^Beckwith, Martha (1940)."Guardian Gods".Archivedfrom the original on May 27, 2009.RetrievedAugust 13,2009.

- ^"Pele, Goddess of Fire".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-01.Retrieved2006-09-13.

- ^"Traditions of O'ahu: Stories of an Ancient Island".Archived fromthe originalon September 18, 2009.RetrievedAugust 14,2009.

- ^Taylor, Leighton R. (November 1993).Sharks of Hawaii: Their Biology and Cultural Significance.University of Hawaii Press.ISBN978-0-8248-1562-2.

- ^ab"National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Turtle and Shark (American Samoa)"(PDF).United States National Park Service. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2018-10-25.RetrievedOctober 25,2018.

- ^"The Turtle And The Shark".Ryanwoodwardart.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-10-25.RetrievedOctober 25,2018.

- ^"Samoa - Some Legends of Samoa".Janesocienia.coam.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-11-28.RetrievedOctober 25,2018.

- ^Crawford, Dean (2008).Shark.Reaktion Books. pp. 47–55.ISBN978-1861893253.

- ^Jøn, A. Asbjørn; Aich, Raj S. (2015)."Southern shark lore forty years after Jaws: The positioning of sharks within Murihiku, New Zealand".Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies(30).

- ^Finkelstein JB (2005)."Sharks do get cancer: few surprises in cartilage research".Journal of the National Cancer Institute.97(21): 1562–3.doi:10.1093/jnci/dji392.PMID16264172.

- ^Ostrander GK; Cheng KC; Wolf JC; Wolfe MJ (2004)."Shark cartilage, cancer and the growing threat of pseudoscience".Cancer Research.64(23): 8485–91.doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2260.PMID15574750.

- ^"Do Sharks Hold Secret to Human Cancer Fight?".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-16.Retrieved2006-09-08.

- ^"Alternative approaches to prostate cancer treatment".Archived fromthe originalon June 2, 2008.Retrieved2008-06-23.

- ^Pollack, Andrew (3 June 2007)."Shark Cartilage, Not a Cancer Therapy".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 11 December 2008.Retrieved2009-08-29.

- ^The results of a study sponsored by theNational Cancer Institute,and led by Dr. Charles Lu of theM.D. Anderson Cancer CenterinHouston, Texas,were presented at the annual meeting of theAmerican Society of Clinical Oncologyon June 2, 2007 inChicago.Cancer patients treated with extracts from shark cartilage had ashortermedian lifespan than patients receiving a placebo."Shark fin won't help fight cancer, but ginseng will".Retrieved2008-06-23.[dead link]

- ^HowStuffWorks "How many sharks are killed recreationally each year - and why?".Animals.howstuffworks. Retrieved on 2010-09-16.ArchivedMarch 7, 2013, at theWayback Machine

- ^ab"Shark fin soup alters an ecosystem—CNN".CNN.2008-12-15.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-03-26.Retrieved2010-05-23.

- ^Worm, Boris; Davis, Brendal; Kettemer, Lisa; Ward-Paige, Christine A.; Chapman, Demian; Heithaus, Michael R.; Kessel, Steven T.; Gruber, Samuel H. (2013). "Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks".Marine Policy.40:194–204.doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.034.

- ^abNicholas K Dulvy; Sarah L Fowler; John A Musick; Rachel D Cavanagh; Peter M Kyne; Lucy R Harrison; John K Carlson; Lindsay NK Davidson; Sonja V Fordham; Malcolm P Francis; Caroline M Pollock; Colin A Simpfendorfer; George H Burgess; Kent E Carpenter; Leonard JV Compagno; David A Ebert; Claudine Gibson; Michelle R Heupel; Suzanne R Livingstone; Jonnell C Sanciangco; John D Stevens; Sarah Valenti; William T White (2014)."Extinction risk and conservation of the world's sharks and rays".eLife.3:e00590.doi:10.7554/eLife.00590.PMC3897121.PMID24448405.

eLife 2014;3:e00590

- ^"Endangered shark meat sold in Australian fish and chip shops, study finds".Sky News.Retrieved2023-07-27.

- ^Herz, Rachel (28 January 2012)."You eat that?".The Wall Street Journal.Archived fromthe originalon 17 March 2015.Retrieved30 January2012.

- ^abBakalar, Nicholas (October 12, 2006)."38 Million Sharks Killed for Fins Annually, Experts Estimate".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon October 17, 2012.Retrieved2012-12-02.

- ^[1]ArchivedAugust 4, 2008, at theWayback Machine

- ^Ask your senator to support the Shark Conservation Act

- ^"Hawaii: Shark Fin Soup Is Off the Menu".The New York Times.Associated Press. May 28, 2010.Archivedfrom the original on July 1, 2017.RetrievedJune 20,2010.Research exemptions are available.

- ^"Sharks and Rays - Species we work with at TRAFFIC".traffic.org.Archived fromthe originalon 2019-01-10.Retrieved2019-01-10.

- ^Mondo, Kiyo; Hammerschlag, Neil; Basile, Margaret; Pablo, John; Banack, Sandra A.; Mash, Deborah C. (2012)."Cyanobacterial Neurotoxin β-N-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in Shark Fins".Marine Drugs.10(2): 509–520.doi:10.3390/md10020509.PMC3297012.PMID22412816.

- ^"Neurotoxins in shark fins: A human health concern".Science Daily.February 23, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on August 9, 2019.RetrievedAugust 9,2019.

- ^"Shark fisheries and trade in Europe: Fact sheet on Italy".Archivedfrom the original on 2007-09-27.Retrieved2007-09-06.

- ^Walker, T.I. (1998).Shark Fisheries Management and Biology.

- ^France Porcher, Illa (2014-01-24)."One Quarter of Sharks and Rays Face Extinction".Archived fromthe originalon 2014-01-26.Retrieved2014-01-24.

- ^Morales, Alex."Extinction Threatens 1/4 of Sharks and Rays on Red List".Bloomberg L.P.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2014.Retrieved24 January2014.

- ^Brown, Sophie (8 May 2014)."Australia: Over 170 sharks caught under controversial cull program".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2017.Retrieved31 December2016.