Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo Thẩm quát | |

|---|---|

Bust of Shen at theBeijing Ancient Observatory | |

| Born | 1031 |

| Died | 1095 (aged 63–64) Runzhou,Song Empire |

| Known for | Geomorphology,Climate change,Atmospheric refraction,True north,Retrogradation,Camera obscura,Raised-relief map,fi xing the position of thepole star,correctinglunarandsolarerrors |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Agronomy,Astronomy,Archaeology,Anatomy,Antiquarianism,Mathematics,Pharmacology,Medical science,Entomology,Mineralogy,Music,Geomorphology,Sedimentology,Optical engineering,Soil science,Encyclopedism,Geomagnetics,Optics,Hydraulics,Hydraulic engineering,Mechanical engineering,Metallurgy,Metaphysics,Meteorology,Climatology,Cartography,Botany,Zoology,Economics,Finance,Military strategy,Ethnography,Divination,Art criticism,Philosophy,Poetry,Politics,Public Administration |

| Institutions | Hanlin Academy |

| Shen Kuo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Shen Kuo" inregularChinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | Thẩm quát | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

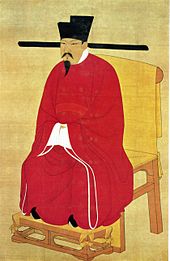

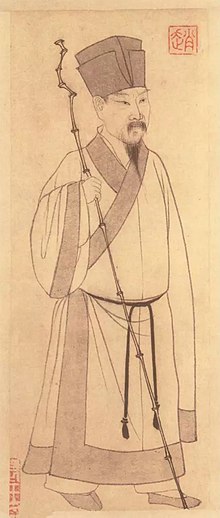

Shen Kuo[a](Chinese:Thẩm quát;1031–1095) orShen Gua[b],courtesy nameCunzhong( tồn trung ) andpseudonymMengqi(now usually given asMengxi)Weng( mộng khê ông ),[1]was a Chinesepolymath,scientist, and statesman of theSong dynasty(960–1279). Shen was a master in many fields of study includingmathematics,optics,andhorology.In his career as a civil servant, he became afinance minister,governmental state inspector, head official for theBureau of Astronomyin the Song court, Assistant Minister of Imperial Hospitality, and also served as anacademic chancellor.[2]At court his political allegiance was to the Reformist faction known as theNew Policies Group,headed byChancellorWang Anshi(1021–1085).

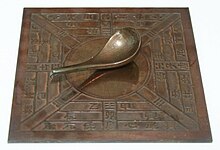

In hisDream Pool EssaysorDream Torrent Essays[3](Mộng khê bút đàm;Mengxi Bitan) of 1088, Shen was the first to describe the magnetic needlecompass,which would be used for navigation (first described in Europe byAlexander Neckamin 1187).[4][5]Shen discovered the concept oftrue northin terms ofmagnetic declinationtowards thenorth pole,[5]with experimentation of suspended magnetic needles and "the improvedmeridiandetermined by Shen's [astronomical] measurement of the distance between thepole starand true north ".[6]This was the decisive step in human history to make compasses more useful for navigation, and may have been a concept unknown in Europefor another four hundred years(evidence of German sundials made circa 1450 show markings similar toChinese geomancers' compasses in regard to declination).[7]

Alongside his colleagueWei Pu,Shen planned to map the orbital paths of the Moon and the planets in an intensive five-year project involving daily observations, yet this was thwarted by political opponents at court.[8]To aid his work in astronomy, Shen Kuo made improved designs of thearmillary sphere,gnomon,sighting tube, andinvented a new typeof inflowwater clock.Shen Kuo devised ageologicalhypothesis for land formation (geomorphology), based upon findings of inlandmarinefossils,knowledge ofsoil erosion,and thedepositionofsilt.[9]He also proposed a hypothesis of gradualclimate change,after observing ancientpetrifiedbamboosthat were preserved underground in a dry northern habitat that would not support bamboo growth in his time. He was the first literary figure in China to mention the use of thedrydockto repair boats suspended out of water, and also wrote of the effectiveness of the relatively new invention of the canalpound lock.Although not the first to inventcamera obscura,Shen noted the relation of thefocal pointof aconcave mirrorand that of the pinhole. Shen wrote extensively aboutmovable typeprintinginvented byBi Sheng(990–1051), and because of his written works the legacy of Bi Sheng and the modern understanding of the earliest movable type has been handed down to later generations.[10]Following an old tradition in China, Shen created araised-relief mapwhile inspecting borderlands. His description of an ancient crossbow mechanism he unearthed asan amateur archaeologistproved to be aJacob's staff,asurveyingtool which wasn't known in Europe until described byLevi ben Gersonin 1321.

Shen Kuo wrote several other books besides theDream Pool Essays,yet much of the writing in his other books has not survived. Some of Shen'spoetrywas preserved in posthumous written works. Although much of his focus was on technical and scientific issues, he had an interest indivinationand the supernatural, the latter including his vivid description ofunidentified flying objectsfrom eyewitness testimony. He also wrote commentary on ancientDaoistandConfuciantexts.

Life

[edit]Birth and youth

[edit]

Shen Kuo was born in Qiantang (modern-dayHangzhou) in the year 1031. His father Shen Zhou (Thẩm chu;978–1052) was a somewhat lower-classgentryfigure serving in official posts on the provincial level; his mother was from a family of equal status inSuzhou,with her maiden name beingXu(Hứa).[11]Shen Kuo received his initial childhood education from his mother, which was a common practice in China during this period.[11][c]She was very educated herself, teaching Kuo and his brother Pi (Khoác) the military doctrines of her own elder brother Xu Dong (Hứa động;975–1016).[11]Since Shen was unable to boast of a prominent familial clan history like many of his elite peers born in the north, he was forced to rely on his wit and stern determination to achieve in his studies, subsequently passing theimperial examinationsand enter the challenging and sophisticated life of anexam-drafted state bureaucrat.[11]

From about 1040 AD, Shen's family moved aroundSichuanprovince and finally to the international seaport atXiamen,where Shen's father accepted minor provincial posts in each new location.[12]Shen Zhou also served several years in the prestigious capitaljudiciary,the equivalent of a national supreme court.[11]Shen Kuo took notice of the various towns and rural features of China as his family traveled, while he became interested during his youth in the diversetopographyof the land.[12]He also observed the intriguing aspects of his father's engagement in administrative governance and the managerial problems involved; these experiences had a deep impact on him as he later became a government official.[12]Since he often became ill as a child, Shen Kuo also developed a natural curiosity about medicine and pharmaceutics.[12]

Shen Zhou died in the late winter of 1051 (or early 1052), when his son Shen Kuo was 21 years old. Shen Kuo grieved for his father, and followingConfucianethics, remained inactive in a state of mourning for three years until 1054 (or early 1055).[13]As of 1054, Shen began serving in minor local governmental posts. However, his natural abilities to plan, organize, and design were proven early in life; one example is his design and supervision of the hydraulic drainage of anembankmentsystem,which convertedsome one hundred thousandacres(400 km2) ofswamplandinto primefarmland.[13]Shen Kuo noted that the success of thesiltfertilizationmethod relied upon the effective operation ofsluicegates of irrigationcanals.[14]

Official career

[edit]

In 1063 Shen Kuo successfully passed theimperial examinations,the difficult national-level standard test that every high official was required to pass in order to enter the governmental system.[13]He not only passed the exam however, but was placed into the higher category of the best and brightest students.[13]While serving atYangzhou,Shen's brilliance and dutiful character caught the attention of Zhang Chu (Trương sô;1015–1080), the Fiscal Intendant of the region. Shen made a lasting impression upon Zhang, who recommended Shen for a court appointment in the financial administration of the central court.[13]Shen would also eventually marry Zhang's daughter, who became his second wife.

In his career as ascholar-officialfor the central government, Shen Kuo was also an ambassador to theWestern Xiadynasty andLiao dynasty,[15]a military commander, a director of hydraulic works, and the leading chancellor of theHanlin Academy.[16]By 1072, Shen was appointed as the head official of the Bureau of Astronomy.[13]With his leadership position in the bureau, Shen was responsible for projects in improving calendrical science,[10]and proposed many reforms to theChinese calendaralongside the work of his colleagueWei Pu.[8]With his impressive skills and aptitude for matters of economy and finance, Shen was appointed as the Finance Commissioner at the central court.[17]

As written by Li Zhiyi, a man married to Hu Wenrou (granddaughter of Hu Su, a famous minister of the Song dynasty), Shen Kuo was Li's mentor while Shen served as an official.[18]According to Li's epitaph for his wife, Shen would sometimes relay questions via Li to Hu when he needed clarification for his mathematical work, as Hu Wenrou was esteemed by Shen as a remarkable female mathematician.[18]Shen lamented: "If only she were a man, Wenrou would be my friend."[18]

While employed by the central government, Shen Kuo was also sent out with others to inspect the granary system of the empire, investigating problems of illegal tax-collection, negligence, ineffective disaster relief, and inadequate water-conservancy projects.[19]While Shen was appointed as the regional inspector of Zhe gian g in 1073, the Emperor requested that Shen pay a visit to the famous poetSu Shi(1037–1101), then an administrator in Hangzhou.[20]Shen took advantage of this meeting to copy some of Su's poetry, which he presented to the Emperor indicating that it expressed "abusive and hateful" speech against the Song court; these poems were later politicized by Li Ding and Shu Dan in order to level a court case against Su. (TheCrow Terrace Poetry Trial,of 1079.)[20]With his demonstrations of loyalty and ability, Shen Kuo was awarded the honorary title of a State FoundationViscountbyEmperor Shenzong of Song(r. 1067–1085), who placed a great amount of trust in Shen Kuo.[17]He was even made 'companion to the heir apparent' ( Thái Tử công chính; 'Taizi zhongyun').[1]

At court Shen was a political favorite of the ChancellorWang Anshi(1021–1086), who was the leader of the political faction of Reformers, also known as the New Policies Group (Tân pháp,Xin Fa).[21][d]Shen Kuo had a previous history with Wang Anshi, since it was Wang who had composed the funeraryepitaphfor Shen's father, Zhou.[22]Shen Kuo soon impressed Wang Anshi with his skills and abilities as an administrator and government agent. In 1072, Shen was sent to supervise Wang's program of surveying the building of silt deposits in theBian Canaloutside the capital city. Using an original technique, Shen successfully dredged the canal and demonstrated the formidable value of the silt gathered as afertilizer.[22]He gained further reputation at court once he was dispatched as an envoy to theKhitanLiao dynasty in the summer of 1075.[22]The Khitans had made several aggressive negotiations of pushing their borders south, while manipulating several incompetent Song ambassadors who conceded to the Liao Kingdom's demands.[22]In a brilliant display of diplomacy, Shen Kuo came to the camp of the Khitan monarch at Mt. Yongan (near modernPingquan,Hebei), armed with copies of previously archived diplomatic negotiations between the Song and Liao dynasties.[22]Shen Kuo refutedEmperor Daozong'sbluffs point for point, while the Song reestablished their rightful border line.[22]In regard to theLý dynastyofĐại Việt(in modern northernVietnam), Shen demonstrated in hisDream Pool Essaysthat he was familiar with the key players (on the Vietnamese side) in the prelude to theSino-Vietnamese War of 1075–1077.[23]With his reputable achievements, Shen became a trusted member of Wang Anshi's elite circle of eighteen unofficial core political loyalists to the New Policies Group.[22]

Although much of Wang Anshi's reforms outlined in theNew Policiescentered on state finance, land tax reform, and the Imperial examinations, there were also military concerns. This included policies of raisingmilitiasto lessen the expense of upholding a million soldiers,[24]putting government monopolies onsaltpetreandsulphurproduction and distribution in 1076 (to ensure thatgunpowdersolutions would not fall into the hands of enemies),[25][26]and aggressive military policy towards Song's northern rivals of the Western Xia and Liao dynasties.[27]A few years after Song dynasty military forces had made victorious territorial gains against theTangutsof the Western Xia, in 1080 Shen Kuo was entrusted as a military officer in defense of Yanzhou (modern-dayYan'an,Shaanxiprovince).[28]During the autumn months of 1081, Shen was successful in defending Song dynasty territory while capturing several fortified towns of the Western Xia.[17]The Emperor Shenzong of Song rewarded Shen with numerous titles for his meritin these battles,and in the sixteen months of Shen's military campaign, he received 273 letters from the Emperor.[17]However, Emperor Shenzong trusted an arrogant military officer who disobeyed the emperor and Shen's proposal for strategic fortifications, instead fortifying what Shen considered useless strategic locations. Furthermore, this officer expelled Shen from his commanding post at the maincitadel,so as to deny him any glory in chance of victory.[17]The result of this was nearly catastrophic, as the forces of the arrogant officer were decimated;[17]Xinzhong Yao states that the death toll was 60,000.[1]Nonetheless, Shen was successful in defending his fortifications and the only possible Tangut invasion-route to Yanzhou.[17]

Impeachment and later life

[edit]

The new Chancellor Cai Que (Thái xác;1036–1093) held Shen responsible for the disaster and loss of life.[17]Along with abandoning the territory which Shen Kuo had fought for, Cai ousted Shen from his seat of office.[17]Shen's life was now forever changed, as he lost his once reputable career in state governance and the military.[17]Shen was then put underprobationin a fixed residence for the next six years. However, as he was isolated from governance, he decided to pick up theink brushand dedicate himself to intensive scholarly studies. After completing twogeographicalatlasesfor a state-sponsored program, Shen was rewarded by having his sentence of probation lifted, allowing him to live in a place of his choice.[17]Shen was also pardoned by the court for any previous faults or crimes that were claimed against him.[17]

In his more idle years removed from court affairs, Shen Kuo enjoyed pastimes ofthe Chinese gentry and literatithat would indicate his intellectual level and cultural taste to others.[30]As described in hisDream Pool Essays,Shen Kuo enjoyed the company of the "nine guests" ( chín khách,jiuke), a figure of speech for theChinese zither,the older 17x17 line variant ofweiqi(known today asgo),ZenBuddhist meditation,ink (calligraphyandpainting),tea drinking,alchemy,chanting poetry,conversation, anddrinking wine.[29]These nine activities were an extension to the older so-calledFour Arts of the Chinese Scholar.

In the 1070s, Shen had purchased a lavish garden estate on the outskirts of modern-dayZhen gian g,Jiangsuprovince, a place of great beauty which he named "Dream Brook" ( "Mengxi" ) after he visited it for the first time in 1086.[17]Shen Kuo permanently moved to the Dream Brook Estate in 1088, and in that same year he completed his life's written work of theDream Pool Essays,naming the book after his garden-estate property. It was there that Shen Kuo spent the last several years of his life in leisure, isolation, and illness, until his death in 1095.[17]

Scholarly achievements

[edit]Shen Kuo wrote extensively on a wide range of different subjects. His written work included two geographicalatlases,a treatise onmusicwith mathematicalharmonics,governmental administration, mathematical astronomy, astronomical instruments, martialdefensive tacticsandfortifications,painting,tea,medicine,and muchpoetry.[31]His scientific writings have been praised bysinologistssuch asJoseph NeedhamandNathan Sivin,and he has been compared by Sivin to polymaths such as his Song dynasty Chinese contemporarySu Song,as well as toGottfried LeibnizandMikhail Lomonosov.[32]

Raised-relief map

[edit]

Joseph Needham suggests that certain pottery vessels of theHan dynasty(202 BC – 220 AD) showing artificial mountains as lid decorations may have influenced the development of theraised-relief mapin China.[33]The Han dynasty generalMa Yuan(14 BC – 49 AD) is recorded as having made a raised-relief map of valleys and mountains in a rice-constructed model of 32 AD.[34]Shen Kuo's largest atlas included twenty three maps of China and foreign regions that were drawn at a uniform scale of 1:900,000.[6]Shen also created a raised-relief map using sawdust, wood, beeswax, and wheat paste.[6][35]Zhu Xi(1130–1200) was inspired by the raised-relief map of Huang Shang and so made his own portable map made of wood and clay which could be folded up from eight hinged pieces.[36]

Pharmacology

[edit]Forpharmacology,Shen wrote of the difficulties of adequatediagnosisandtherapy,as well as the proper selection, preparation, and administration of drugs.[37]He held great concern for detail andphilologicalaccuracy in identification, use and cultivation of different types of medicinal herbs, such as in which months medicinal plants should be gathered, their exact ripening times, which parts should be used for therapy; for domesticated herbs he wrote about planting times, fertilization, and other matters ofhorticulture.[38]In the realms ofbotany,zoology,andmineralogy,Shen Kuo documented and systematically described hundreds of different plants, agricultural crops, rare vegetation, animals, andmineralsfound in China.[39][40][41][42]For example, Shen noted that the mineralorpimentwas used to quickly erase writing errors on paper.[43]

Civil engineering

[edit]

The writing of Shen Kuo is the only source for the date when thedrydockwas first used in China.[44]Shen Kuo wrote that during the Xi-Ning reign (1068–1077), the court official Huang Huaixin devised a plan for repairing 60 m (200 ft) longpalatialboats that were a century old; essentially, Huang Huaixin devised the first Chinese drydock for suspending boats out of water.[44]These boats were then placed in a roof-covered dock warehouse to protect them from weathering.[44]Shen also wrote about the effectiveness of the new invention (i.e. by the 10th century engineerQiao Weiyo) of thepound lockto replace the oldflash lockdesign used in canals.[45]He wrote that it saved the work of five hundred annual labors, annual costs of up to 1,250,000 strings of cash, and increased the size limit of boats accommodated from 21tons/21000kgto 113tons/115000kg.[45]

If it were not for Shen Kuo's analysis and quoting in hisDream Pool Essaysof the writings of thearchitectYu Hao(fl.970), the latter's work would have been lost to history.[46][e]Yu designed a famous woodenpagodathat burned down in 1044 and was replaced in 1049 by a brick pagoda (the 'Iron Pagoda') of similar height, but not of his design. From Shen's quotation—or perhaps Shen's own paraphrasing of Yu Hao'sTimberwork Manual( mộc kinh;Mujing)—shows that already in the 10th century there was a graded system of building unit proportions, a system which Shen states had become more precise in his time but stating no one could possibly reproduce such a sound work.[47][48]However, he did not anticipate the more complex and matured system of unit proportions embodied in the extensive written work by scholar-official Li Jie (1065–1110), theTreatise on Architectural Methods( xây dựng kiểu Pháp;Yingzao Fashi) of 1103.[48][49]Klaas Ruitenbeek states that the version of theTimberwork Manualquoted by Shen is most likely Shen's summarization of Yu's work or a corrupted passage of the original by Yu Hao, as Shen writes: "According to some, the work was written by Yu Hao."[47]

Anatomy

[edit]The Chinese had long taken an interest in examining the human body. For example, in 16 AD, theXin dynastyusurperWang Mangcalled for the dissection of an executed man, to examine his arteries and viscera in order to discover cures for illnesses.[50]Shen also took interest in humananatomy,dispelling the long-held Chinese theory that the throat contained three valves, writing, "When liquid and solid are imbibed together, how can it be that in one's mouth they sort themselves into two throat channels?"[38]Shen maintained that thelarynxwas the beginning of a system that distributed vitalqifrom the air throughout the body, and that theesophaguswas a simple tube that dropped food into the stomach.[51]Following Shen's reasoning and correcting the findings of thedissectionof executed bandits in 1045, an early 12th-century Chinese account of a bodily dissection finally supported Shen's belief in two throat valves, not three.[52]Also, the later Song dynasty judge and earlyforensicexpertSong Ci(1186–1249) would promote the use ofautopsyin order to solvehomicidecases, as written in hisCollected Cases of Injustice Rectified.[53]

Mathematics

[edit]

In the broad field ofmathematics,Shen Kuo mastered many practical mathematical problems, including many complex formulas forgeometry,[54]circle packing,[55]and chords and arcs problems employingtrigonometry.[56]Shen addressed problems of writing out very large numbers, as large as (104)43.[57]Shen's "technique of small increments" laid the foundation in Chinese mathematics for packing problems involving equal difference series.[57]Sal Restivo writes that Shen used summation of higher series to ascertain the number of kegs which could be piled in layers in a space shaped like thefrustumof a rectangular pyramid.[58][59]In his formula "technique of intersecting circles", he created an approximation of the arc of a circlesgiven the diameterd,sagittav,and length of the chordcsubtending the arc, the length of which he approximated ass=c+ 2v2/d.[57]Restivo writes that Shen's work in the lengths of arcs of circles provided the basis forspherical trigonometrydeveloped in the 13th century byGuo Shoujing(1231–1316).[58]He also simplified thecounting rodstechnique by outlining short cuts in algorithm procedures used on the counting board, an idea expanded on by the mathematicianYang Hui(1238–1298).[60]Victor J. Katz asserts that Shen's method of "dividing by 9, increase by 1; dividing by 8, increase by 2," was a direct forerunner to the rhyme scheme method of repeated addition "9, 1, bottom add 1; 9, 2, bottom add 2".[61]

Shen wrote extensively about what he had learned while working for the state treasury, including mathematical problems posed by computingland tax,estimating requirements,currencyissues,metrology,and so forth.[62]Shen once computed the amount ofterrainspace required for battle formations inmilitary strategy,[63]and also computed the longest possible military campaign given the limits of human carriers who would bring their own food and food for other soldiers.[64]Shen wrote about the earlierYi Xing(672–717), a Buddhist monk who applied an earlyescapementmechanism to a water-poweredcelestial globe.[65]By using mathematicalpermutations,Shen described Yi Xing's calculation of possible positions on agoboard game.Shen calculated the total number for this using up to five rows and twenty five game pieces, which yielded the number 847,288,609,443.[66][67]

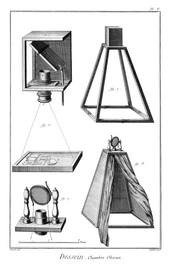

Optics

[edit]Shen Kuo experimented with thepinhole cameraandburning mirroras the ancient ChineseMohistshad done in the 4th century BC, asMoziof China'sWarring States periodwas perhaps the first to describe the concept ofcamera obscura,if not his Greek contemporaryAristotle.[68]TheIraqiMuslimscientistIbn al-Haytham(965–1039) further experimented with camera obscura and was the first to attributegeometricalandquantitativeproperties to it, but Shen was first to note the relationship of the three separate radiation phenomena: the focal point, burning point, and pinhole.[69]Using a fitting metaphor, Shen compared optical image inversion to anoarlockandwaisted drum.[70]Along withfocal points,he also noted that the image in aconcave mirroris inverted.[71]Shen, who never asserted that he was the first to experiment with camera obscura, hints in his writing that camera obscura was dealt with in theMiscellaneous Morsels from Youyangwritten byDuan Chengshi(d. 863) during theTang dynasty(618–907), in regard to the inverted image of aChinese pagodaby a seashore.[72]Chinese authors from the 12th to 17th centuries would discuss the optical observations made by Shen Kuo but not advance them further, whileLeonardo da Vinci(1452–1519) would be the first in Europe to make a similar observation about the focal point and pinhole in camera obscura.[69]

Magnetic needle compass

[edit]Since the time of the engineer and inventorMa Jun(c. 200–265), the Chinese had used thesouth-pointing chariot,which did not employ magnetism, as a compass. In 1044 theCollection of the Most Important Military Techniques(Võ kinh tổng muốn;Wujing Zongyao) recorded that fish-shaped objects cut from sheet iron, magnetized bythermoremanence(essentially, heating that produced weak magnetic force), and placed in a water-filled bowl enclosed by a box were used for directional pathfinding alongside the south-pointing chariot.[73][74]

However, it was not until the time of Shen Kuo that the earliestmagneticcompasseswould be used fornavigation.In his written work, Shen Kuo made the first known explicit reference to the magnetic compass-needle and the concept oftrue north.[16][75][76]He wrote that steel needles were magnetized once they were rubbed withlodestone,and that they were put in floating position or in mountings; he described the suspended compass as the best form to be used, and noted that the magnetic needle of compasses pointed either south or north.[73][77]Shen Kuo asserted that the needle will point south but with a deviation,[77]stating "[the magnetic needles] are always displaced slightly east rather than pointing due south."[73]

Shen Kuo wrote that it was preferable to use the twenty-four-point rose instead of the old eight compass cardinal points — and the former was recorded in use for navigation shortly after Shen's death.[6]The preference of use for the twenty-four-point-rose compass may have arisen from Shen's finding of a more accurateastronomical meridian,determined by his measurement between the pole star and true north;[6]however, it could also have been inspired bygeomanticbeliefs and practices.[6]The book of the authorZhu Yu,thePingzhou Table Talkspublished in 1119 (written from 1111 to 1117), was the first record of use of a compass for seafaring navigation.[76][78]However, Zhu Yu's book recounts events back to 1086, when Shen Kuo was writing theDream Pool Essays;this meant that in Shen's time the compass might have already been in navigational use.[78]In any case, Shen Kuo's writing on magnetic compasses has proved invaluable for understanding China's earliest use of the compass for seafaring navigation.

Archaeology

[edit]

Many of Shen Kuo's contemporaries were interested inantiquarianpursuits of collecting old artworks.[80]They were also interested inarchaeologicalpursuits, although for rather different reasons than why Shen Kuo held an interest inarchaeology.While Shen's educatedConfuciancontemporaries were interested in obtaining ancient relics and antiques in order to revive their use in rituals, Shen was more concerned with how items from archeological finds were originally manufactured and what their functionality would have been, based onempirical evidence.[81]Shen Kuo criticized those in his day who reconstructed ancient ritual objects using only their imagination and not the tangible evidence from archeological digs or finds.[81]Shen also disdained the notion of others that these objects were products of the "sages" or thearistocratic class of antiquity,rightfully crediting the items' manufacture and production to the common working people and artisans of previous eras.[81]Some author writes that Shen Kuo "advocated the use of aninterdisciplinaryapproach to archaeology and practiced such an approach himself through his work inmetallurgy,optics, and geometry in the study of ancient measures. "[81]

While working in the Bureau of Astronomy, Shen Kuo's interest in archaeology and old relics led him to reconstruct an armillary sphere from existing models as well as from ancient texts that could provide additional information.[81]Shen used ancient mirrors while conducting his optics experiments.[81]He observed ancient weaponry, describing thescaled sight deviceson ancientcrossbowsand the ancients' production of swords with composite blades that had a midrib ofwrought ironandlow-carbonsteelwhile having two sharp edges ofhigh-carbonsteel.[81]Being a knowledgeable musician, Shen also suggested suspendingan ancient bellby using a hollow handle.[81]In his assessment of the carvedreliefsof the ancient Zhuwei Tomb, Shen stated that the reliefs demonstrate genuineHan dynasty era clothing.[82]

After unearthing an ancient crossbow device from a house's garden in Haichow, Jiangsu, Shen discovered that the cross-wire grid sighting device, marked in graduated measurements on the stock, could be used to calculate the height of a distant mountain in the same way that mathematicians could apply right-angle triangles to measure height.[83]Needham asserts Shen had discovered the survey device known asJacob's staff,which was not described elsewhere until theProvençalJewish mathematicianLevi ben Gerson(1288–1344) wrote of it in 1321.[84]Shen wrote that while viewing the whole of a mountain, the distance on the instrument was long, but while viewing a small part of the mountainside the distance was short due to the device's cross piece that had to be pushed further away from the observer's eye, with the graduation starting on the further end.[83]He wrote that if one placed an arrow on the device and looked past its end, the degree of the mountain could be measured and thus its height could be calculated.[83]

Geology

[edit]

The ancientGreekAristotle(384 BC–322 BC) wrote in hisMeteorologyof how the earth had the potential for physical change, including the belief that all rivers and seas at one time did not exist where they were, and were dry. The Greek writerXenophanes(570 BC–480 BC) wrote of how inlandmarinefossilswere evidence that massive periodicfloodinghad wiped out mankind several times in the past, but never wrote of land formation or shifting seashores.[85]Du Yu(222–285) a ChineseJin dynastyofficer, believed that the land of hills would eventually be leveled into valleys and valleys would gradually rise to form hills.[86]The Daoist alchemistGe Hong(284–364) wrote of the legendary immortalMagu;in a written dialogue by Ge, Ma Gu described how what was once the Eastern Sea (i.e.East China Sea) had transformed into solid land wheremulberry treesgrew, and would one day be filled with mountains and dry, dusty lands.[87]The laterPersianMuslimscholarAbū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī(973–1048) hypothesized thatIndiawas once covered by theIndian Oceanwhile observing rock formations at the mouths of rivers.[88]

It was Shen Kuo who formulated a hypothesis about the process of land formation (geomorphology) based upon several observations as evidence. This included his observation offossilshells in ageologicalstratum of a mountain hundreds of miles from the ocean. He inferred that the land was reshaped and formed byerosionof the mountains, uplift, and the deposition ofsilt,after observing strange natural erosions of theTaihang Mountainsand the Yandang Mountain nearWenzhou.[89]He hypothesized that, with the inundation of silt, the land of the continent must have been formed over an enormous span of time.[90]While visiting the Taihang Mountains in 1074, Shen Kuo noticed strata ofbivalveshells andovoidrocks in a horizontal-running span through a cliff like a large belt.[90]Shen proposed that the cliff was once the location of an ancient seashore that by his time had shifted hundreds of miles east.[90]Shen wrote that in the Zhiping reign period (1064–1067) a man of Zezhou unearthed an object in his garden that looked like a serpent or dragon, and after examining it, concluded the dead animal had apparently turned to "stone".[91][92]The magistrate ofJincheng,Zheng Boshun, examined the creature as well, and noted the same scale-like markings that were seen on other marine animals.[91][92]Shen Kuo likened this to the "stone crabs" found in China.[91][92]

Shen also wrote that since petrified bamboos were found underground in a climatic area where they had never been known to be grown, theclimate there must have shifted geographically over time.[93]Around the year 1080, Shen Kuo noted that a landslide on the bank of a large river near Yanzhou (modernYan'an) had revealed an open space several dozens of feet under the ground once the bank collapsed.[93]This underground space contained hundreds of petrified bamboos still intact with roots and trunks, "all turned to stone" as Shen Kuo wrote.[93]Shen Kuo noted that bamboos do not grow in Yanzhou, located in northern China, and he was puzzled during which previous dynasty the bamboos could have grown.[93]Considering that damp and gloomy low places provide suitable conditions for the growth of bamboo, Shen deduced that the climate of Yanzhou must have fit that description in very ancient times.[93]Although this would have intrigued many of his readers, the study ofpaleoclimatologyin medieval China did not develop into an established discipline.[93]

The Song dynasty philosopherZhu Xi(1130–1200) wrote of this curious natural phenomenon of fossils as well. He was known to have read the works of Shen Kuo.[92]Shen's description of soil erosion and weathering predated that ofGeorgius Agricolain his book of 1546,De veteribus et novis metallis.[94]Furthermore, Shen's theory of sedimentary deposition predated that ofJames Hutton,whose groundbreaking work was published in 1802 (considered the foundation of modern geology).[94]HistorianJoseph Needhamlikened Shen's account to that of theScottishscientistRoderick Murchison(1792–1871), who was inspired to become a geologist after observing a providential landslide.[94]

Meteorology

[edit]

Early speculation and hypothesis pertaining to what is now known asmeteorologyhad a long tradition in China before Shen Kuo. For example, the Han dynasty scholarWang Chong(27–97) accurately described the process of thewater cycle.[95]However, Shen made some observations that were not found elsewhere inChinese literature.For instance, Shen was the first in East Asia to describetornadoes,which were thought to exist only in theWestern hemisphereuntil their observation in China during the first decade of the 20th century.[96]

Shen gave reasoning (earlier proposed by Sun Sikong, 1015–1076) thatrainbowswere formed by the shadow of the sun in rain, occurring when the sun would shine upon it.[97][98][99]Paul Dong writes that Shen's explanation of the rainbow as a phenomenon ofatmospheric refraction"is basically in accord with modern scientific principles."[100]In Europe,Roger Bacon(1214–1294) was the first to suggest that the colors of the rainbow were caused by the reflection and refraction of sunlight through rain drops.[71]

Shen hypothesized that rays of sunlight refract before reaching the surface of the earth, hence people on earth observing the sun are not viewing it in its exact position, in other words, the altitude of the apparent sun is higher than the actual altitude of the sun.[100]Dong writes that "at the time, this discovery was remarkably original."[100]Ibn al-Haytham,in hisBook of Optics(1021), also discussed atmospheric refraction in regard totwilight.[71]

Astronomy and instruments

[edit]

Being the head official for the Bureau of Astronomy, Shen Kuo was an avid scholar of medieval astronomy, and improved the designs of several astronomical instruments. Shen is credited with making improved designs of thegnomon,armillary sphere,andclepsydraclock.[101]For the clepsydra he designed a new overflow-tank type, and argued for a more efficient higher-orderinterpolationinstead of linear interpolation in calibrating the measure of time.[101]Improving the 5th century model of the astronomicalsighting tube,Shen Kuo widened its diameter so that the new calibration could observe thepole starindefinitely.[101]This came about due to the position of the pole star shifting in position since the time ofZu Gengin the 5th century, hence Shen Kuo diligently observed the course of the pole star for three months, plotting the data of its course and coming to the conclusion that it had shifted slightly over three degrees.[101]Apparently this astronomical finding had an impact upon the intellectual community in China at the time. Even Shen's political rival and contemporary astronomerSu Songfeatured Shen's corrected position of the pole star (halfway between Tian shu, at −350 degrees, and the currentPolaris) in the fourthstar mapof his celestial atlas.[102]

The astronomical phenomena of thesolar eclipseandlunar eclipsehad been observed in the 4th century BC by astronomersGan DeandShi Shen;the latter gave instructions on predicting the eclipses based on the relative position of the Moon to the Sun.[103]The philosopher Wang Chong argued against the 'radiating influence' theory ofJing Fang's writing in the 1st century BC and that ofZhang Heng(78–139); the latter two correctly hypothesized that the brightness of the Moon was merely light reflected from the Sun.[104]Jing Fang had written in the 1st century BC of how it was long accepted in China that the Sun and Moon weresphericalin shape ('like acrossbowbullet'), not flat.[105]Shen Kuo also wrote of solar and lunar eclipses in this manner, yet expanded upon this to explain why the celestial bodies were spherical, going against the 'flat earth' theory for celestial bodies.[106]However, there is no evidence to suggest that Shen Kuo supported a round earth theory, which was introduced into Chinese science byMatteo RicciandXu Guangqiin the 17th century.[107]When the Director of the AstronomicalObservatoryasked Shen Kuo if the shapes of the Sun and Moon were round like balls or flat like fans, Shen Kuo explained that celestial bodies were spherical because of knowledge of wa xing and waning of the Moon.[106]Much like what Zhang Heng had said, Shen Kuo likened the Moon to a ball of silver, which does not produce light, but simply reflects light if provided from another source (the Sun).[106]He explained that when the Sun's light is slanting, the Moon appears full.[106]He then explained if one were to cover any sort of sphere with white powder, and then viewed from the side it would appear to be a crescent, hence he reasoned that celestial bodies were spherical.[100][106]He also wrote that, although the Sun and Moon were in conjunction and opposition with each other once a month, this did not mean the Sun would be eclipsed every time their paths met, because of the small obliquity of their orbital paths.[106][108]

Shen is also known for hiscosmologicalhypotheses in explaining the variations ofplanetary motions,includingretrogradation.[109]His colleague Wei Pu realized that the old calculation technique for the mean Sun was inaccurate compared to theapparent Sun,since the latter was ahead of it in the accelerated phase of motion, and behind it in the retarded phase.[110]Shen's hypotheses were similar to the concept of theepicyclein theGreco-Romantradition,[109]only Shen compared the side-section oforbitalpaths of planets and variations of planetary speeds to points in the tips of awillowleaf.[111][112]In a similar rudimentary physical analogy of celestial motions, as John B. Henderson describes it, Shen likened the relationship of the Moon's path to the ecliptic, the path of the Sun, "to the figure of a rope coiled about a tree."[112]

Along with his colleagueWei Puin the Bureau of Astronomy, Shen Kuo planned to plot out the exact coordinates of planetary and lunar movements by recording their astronomical observations three times a night for a continuum of five years.[8]The Song astronomers of Shen's day still retained the lunar theory and coordinates of the earlierYi Xing,which after 350 years had devolved into a state of considerable error.[8]Shen criticized earlier Chinese astronomers for failing to describe celestial movement in spatial terms, yet he did not attempt to provide any reasoning for the motive power of the planets or other celestial movements.[112]Shen and Wei began astronomical observations for the Moon and planets by plotting their locations three times a night for what should have been five successive years.[8]The officials and astronomers at court were deeply opposed to Wei and Shen's work, offended by their insistence that the coordinates of the renowned Yi Xing were inaccurate.[113]They also slandered Wei Pu, out of resentment that a commoner had expertise exceeding theirs.[114]When Wei and Shen made a public demonstration using the gnomon to prove the doubtful wrong, the other ministers reluctantly agreed to correct the lunar and solar errors.[113][115]Despite this success, they eventually dismissed Wei and Shen's tables of planetary motions.[22]Therefore, only the worst and most obvious planetary errors were corrected, and many inaccuracies remained.[114]

Movable type printing

[edit]

Shen Kuo wrote that during the Qingli reign period (1041–1048), underEmperor Renzong of Song(1022–1063), an obscure commoner andartisanknown asBi Sheng(990–1051) invented ceramicmovable typeprinting.[116][117]Although the use of assembling individual characters to compose a piece of text had its origins inantiquity,Bi Sheng's methodical innovation was something completely revolutionary for his time. Shen Kuo noted that the process was tedious if one only wanted to print a few copies of a book, but if one desired to make hundreds or thousands of copies, the process was incredibly fast and efficient.[116]Beyond Shen Kuo's writing, however, nothing is known of Bi Sheng's life or the influence of movable type in his lifetime.[118]Although the details of Bi Sheng's life were scarcely known, Shen Kuo wrote:

When Bi Sheng died, hisfount of typepassed into the possession of my followers (i.e. one of Shen's nephews), among whom it has been kept as a precious possession until now.[2][119]

There are a few surviving examples of books printed in the late Song dynasty using movable type printing.[120]This includes Zhou Bida'sNotes of The Jade Hall(Ngọc Đường tạp ký) printed in 1193 using the method of baked-clay movable type characters outlined in theDream Pool Essays.[121]Yao Shu (1201–1278), an advisor toKublai Khan,once persuaded a disciple Yang Gu to printphilologicalprimersand Neo-Confucian texts by using what he termed the "movable type of Shen Kuo".[122]Wang Zhen(fl. 1290–1333), who wrote the valuable agricultural, scientific, and technological treatise of theNong Shu,mentioned an alternative method of bakingearthenwaretype with earthenware frames in order to make whole blocks.[122]Wang Zhen also improved its use by inventing wooden movable type in the years 1297 or 1298, while he was a magistrate ofJingde,Anhuiprovince.[123]The earlier Bi Sheng had experimented with wooden movable type,[124]but Wang's main contribution was improving the speed of typesetting with simple mechanical devices, along with the complex, systematic arrangement of wooden movable type involving the use of revolving tables.[125]Although later metal movable type would be used in China, Wang Zhen experimented withtinmetal movable type, but found its use to be inefficient.[126]

By the 15th century, metal movable type printing was developed inMing dynastyChina (and earlier inGoryeoKorea,by the mid 13th century), and was widely applied in China by at least the 16th century.[127]InJiangsuandFu gian,wealthy Ming era families sponsored the use of metal type printing (mostly usingbronze). This included the printing works ofHua Sui(1439–1513), who pioneered the first Chinese bronze-type movable printing in the year 1490.[128]In 1718, during the midQing dynasty(1644–1912), the scholar ofTai'anknown as Xu Zhiding developed movable type withenamelwareinstead of earthenware.[122]There was also Zhai Jinsheng (b. 1784), a teacher ofJingxian,Anhui,who spent thirty years making a font of earthenware movable type, and by 1844 he had over 100,000 Chinese writing characters in five sizes.[122]

Despite these advances, movable type printing never gained the amount of widespread use in East Asia thatwoodblock printinghad achieved since the ChineseTang dynastyin the 9th century. Withwritten Chinese,the vast amount of writtenmorphemecharacters impeded movable type's acceptance and practical use, and was therefore seen as largely unsatisfactory.[116]Furthermore, the Europeanprinting press,first invented byJohannes Gutenberg(1398–1468), was eventually wholly adopted as the standard in China, yet the tradition of woodblock printing remains popular in East Asian countries.[116]

Other achievements in science and technology

[edit]Shen Kuo described the phenomena of naturalpredatorinsectscontrolling the population of pests, the latter of which had the potential to wreak havoc upon the agricultural base of China.[129]

Shen also wrote aboutadvancements in metallurgy.While visiting the iron-producing district at Cizhou in 1075, Shen described the "partialdecarburization"method of reforging cast iron under a cold blast, which Hartwell, Needham, andWertimestate is the predecessor of theBessemer process.[130]Shen was worried aboutdeforestation[f]due to the needs of theiron industryand ink makers using pine soot in the production process, so he suggested for the latter an alternative ofpetroleum,which he believed was "produced inexhaustibly within the earth".[97][131]Shen used the soot from the smoke of burned petroleum fuel ( dầu mỏShíyóu,"rock oil" as Shen called it) to invent a new, more durable type of writing ink; theMing dynastypharmacologistLi Shizhen(1518–1593) wrote that Shen's ink was "lustrous likelacquer,and superior to that made from pinewood lamp-black, "or the soot from pinewood.[132][133]

Beliefs and philosophy

[edit]

Shen Kuo was much in favor of philosophicalDaoistnotions which challenged the authority of empirical science in his day. Although much could be discerned through empirical observation and recorded study, Daoism asserted that the secrets of the universe were boundless, something that scientific investigation could merely express in fragments and partial understandings.[134]Shen Kuo referred to the ancient DaoistI Chingin explaining the spiritual processes and attainment of foreknowledge that cannot be attained through "crude traces", which he likens to mathematical astronomy.[134]Nathan Sivin proposes that Shen was the first in history to "make a clear distinction between our unconnected experiences and the unitary causal world we postulate to explain them," which Biderman and Scharfstein state is arguably inherent in the works ofHeraclitus,Plato,andDemocritusas well.[135]Shen was a firm believer in destiny and prognostication, and made rational explanations for the relations between them.[136]Shen held a special interest in fate, mystical divination, bizarre phenomena, yet warned against the tendency to believe that all matters in life were preordained.[137]When describing an event wherelightninghad struck a house and all the wooden walls did not burn (but simply turned black) andlacquerwaresinside were fine, yet metal objects had melted into liquid, Shen Kuo wrote:

Most people can only judge of things by the experiences of ordinary life, but phenomena outside the scope of this are really quite numerous. How insecure it is to investigate natural principles using only the light of common knowledge, and subjective ideas.[138]

In his commentary on the ancient Confucian philosopherMencius(372–289 BC), Shen wrote of the importance of choosing to follow what one knew to be a true path, yet the heart and mind could not attain full knowledge of truth through mere sensory experience.[70]In his own unique way but using terms influenced by the ideas of Mencius, Shen wrote of an autonomous inner authority that formed the basis for one's inclination towards moral choices, a concept linked to Shen's life experiences of surviving and obtaining success through self-reliance.[70]Along with his commentary on theChinese classic texts,Shen Kuo also wrote extensively on the topics of supernaturaldivinationandBuddhistmeditation.[139]

In the "Strange Happenings" passage of theDream Pool Essays,Shen offered accounts of anunidentified flying objectthat occurred during the reign of Emperor Renzong (1022–1063). An object as bright as a pearl was said to occasionally hover over the city ofYangzhouat night, and was previously described by local inhabitants of easternAnhuiand then inJiangsu.[140]A man nearXingkai Lakeobserved the same object, alleging that it emitted powerful lights from its interior like sunbeams illuminating the woods over a ten-mile radius before departing at tremendous speeds.[141]Shen recorded that Yibo, a poet ofGaoyou,wrote a poem about this "pearl" after witnessing it and that locals around Fanliang in Yangzhou erected a "Pearl Pavilion" where spectators on boats hoped to spot the mysterious flying object again.[142]

Art criticism

[edit]

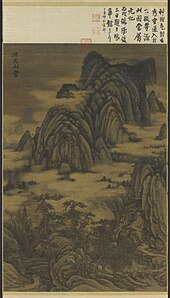

As anart critic,Shen criticized the paintings ofLi Cheng(919–967) for failing to observe the principle of "seeing the small from the viewpoint of the large"in portraying buildings and the like.[143]He praised the works ofDong Yuan(c. 934–c. 962); he noted that although a close-up view of Dong's work would create the impression that his brush techniques were cursory, seen from afar his landscape paintings would give the impression of grand, resplendent, and realistic scenery.[144][145][146]In addition, Shen's writing on Dong's artworks represents the earliest known reference to theJiangnanstyle of painting.[147]In his "Song on Painting" and in hisDream Pool Essays,Shen praised the creative artworks of the Tang painterWang Wei(701–761); Shen noted that Wang was unique in that he "penetrated into the mysterious reason and depth of creative activity," but was criticized by others for not conforming his paintings to reality, such as his painting with a banana tree growing in a snowy, wintry landscape.[148][149][150]

Written works

[edit]Much of Shen Kuo's written work was probably purged under the leadership of ministerCai Jing(1046–1126), who revived the New Policies of Wang Anshi, although he set out on a campaign of attrition to destroy or radically alter the written work of his predecessors and especially Conservative enemies.[151]For example, only six of Shen's books remain, and four of these have been significantly altered since the time they were penned by the author.[152]

In modern times, the best attempt at a complete list and summary of Shen's writing was an appendix written by Hu Daojing in his standard edition ofBrush Talks,written in 1956.[153]

Dream Pool Essays

[edit]Shen Kuo'sDream Pool Essaysconsists of some 507 separate essays exploring a wide range of subjects.[154]It was Shen's ultimate attempt to comprehend and describe a multitude of various aspects of nature, science, and reality, and all the practical and profound curiosities found in the world. The literal translation of the title,Dream Brook Brush Talks,refers to his Dream Brook estate, where he spent the last years of his life. About the title, he is quoted as saying: "Because I had only my writing brush and ink slab to converse with, I call it Brush Talks."[g]

The book was originally 30 chapters long, yet an unknown Chinese author's edition of 1166 edited and reorganized the work into 26 chapters.[155]

Other written works

[edit]

Although theDream Pool Essaysis certainly his most extensive and important work, Shen Kuo wrote other books as well. In 1075, Shen Kuo wrote theXining Fengyuan Li(Hi ninh phụng nguyên lịch;The Oblatory Epoch astronomical system of the Splendid Peace reign period), which was lost, but listed in a 7th chapter of a Song dynasty bibliography.[156]This was the official report of Shen Kuo on his reforms of the Chinese calendar, which were only partially adopted by the Song court's official calendar system.[156]During his years of retirement from governmental service, Shen Kuo compiled aformularyknown as theLiang Fang(Cách hay;Good medicinal formulas).[157]Around the year 1126 it was combined with a similar collection by the famousSu Shi(1037–1101), who was ironically a political opponent to Shen Kuo's faction of Reformers and New Policies supporters at court,[157]yet it was known that Shen Kuo and Su Shi were nonetheless friends and associates.[158]Shen wrote theMengqi Wanghuai Lu(Mộng khê quên lục;Record of longings forgotten at Dream Brook), which was also compiled during Shen's retirement. This book was a treatise in the working since his youth on rural life and ethnographic accounts of living conditions in the isolated mountain regions of China.[159]Only quotations of it survive in theShuo Fu(Nói phu) collection, which mostly describe the agricultural implements and tools used by rural people in high mountain regions. Shen Kuo also wrote theChang xing Ji(Trường hưng tập;Collected Literary Works of [the Viscount of] Chang xing). However, this book was without much doubt a posthumous collection, including various poems, prose, and administrative documents written by Shen.[159]By the 15th century (during theMing dynasty), this book was reprinted, yet only the 19th chapter remained.[159]This chapter was reprinted in 1718, yet poorly edited.[159]Finally, in the 1950s the author Hu Daojing supplemented this small yet valuable work with additions of other scattered poems written by Shen, in the former'sCollection of Shen Kua's Extant Poetry(Shanghai: Shang-hai Shu-tian, 1958).[159]In the tradition of the popular Song era literary category of 'travel record literature' ('youji wenxue'),[160]Shen Kuo also wrote theRegister of What Not to Forget,atraveler's guideto what type ofcarriageis suitable for a journey, the proper foods one should bring, the special clothing one should bring, and many other items.[161]

In hisSequel to Numerous Things Revealed,the Song author Cheng Dachang (1123–1195) noted that stanzas prepared by Shen Kuo for military victory celebrations were later written down and published by Shen.[162]This includes a short poem "Song of Triumph" by Shen Kuo, who uses the musical instrumentmawei huqin('horse-tail barbarian stringed instrument' or 'horse-tail fiddle'[163]) of the northwesternInner Asiannomads as a metaphor for prisoners-of-war led by Song troops:

:Themawei huqinfollowed the Han chariot,

- Its music sounding of complaint to the Khan.

- Do not bend the bow to shoot the goose within the clouds,

- The returning goose bears no letter.

— Shen Kuo[162]

Historian Jonathan Stock notes that the bent bow described in the poem above represents the arched bow used to play thehuqin,while the sound of the instrument itself represented the discontent expressed by the prisoners-of-war with their defeatedkhan.[162]

Legacy

[edit]

Praise, critique, and criticism

[edit]In theRoutledge Curzon Encyclopedia of Confucianism,Xinzhong Yao states that Shen Kuo's legacy was tainted by his eager involvement in Wang Anshi's New Policies reforms, his actions criticized inthe later traditional histories.[1]However, Shen's reputation as a polymath has been well regarded. Joseph Needham stated that Shen Kuo was "one of the greatest scientific minds in Chinese history."[164]TheFrenchsinologistJacques Gernetis of the opinion that Shen possessed an "amazingly modern mind."[165]Yao states of Shen's thorough recording of natural sciences in hisDream Pool Essays:

We must regard Shen Kuo's collection as an indispensable primary source attesting to the unmatched level of attainment achieved by Chinese science prior to the twelfth century.[166]

However, Toby E. Huff writes that Shen Kuo's "scattered set" of writings lacks clear-cut organization and "theoretical acuteness," that is,scientific theory.[167]Nathan Sivin wrote that Shen's originality stands "cheek by jowl with trivial didacticism, court anecdotes, and ephemeral curiosities" that provide little insight.[167]Donald Holzman writes that Shen "has nowhere organized his observations into anything like a general theory."[167]Huff writes that this was a systemic problem of early Chinese science, which lacked systematic treatment that could be found in European works such as theConcordance and Discordant Canonsby the lawyerGratianofBologna(fl. 12th century).[167]In regard to an overarching concept ofsciencewhich could branch together all the various sciences studied by the Chinese, Sivin asserts that the writings of Shen Kuo "do not indicate that he achieved, or even sought, an integrated framework for his diverse knowledge; the one common thread is the varied responsibilities of his career as a high civil servant."[168]

Burial and posthumous honors

[edit]Upon his death, Shen Kuo was interred in a tomb inYuhangDistrict ofHangzhou,at the foot of the Taiping Hill.[169]His tomb was eventually destroyed, yetMing dynastyrecords indicated its location, which was found in 1983 and protected by the government in 1986.[169]The remnants of the tomb's brick structure remained, along with Song dynastyglasswaresandcoins.[169]The Hangzhou Municipal Committee completed a restoration of Shen's tomb in September 2001.

In addition to his tomb, Shen Kuo'sMengxigarden estate, his former two-acre (8,000 m2) property in Zhen gian g, was restored by the government in 1985.[170]However, the renovated Mengxi Garden is only part of the original of Shen Kuo's time.[171]AQing dynasty-era hall built on the site is now used as the main admissions gate.[170]In the Memorial Hall of the gardens, there is a large painting depicting the original garden of Shen Kuo's time, including wells, green bamboo groves, stone-paved paths, and decorated walls of the original halls.[171]In this exhibition hall there stands a 1.4 m (4.6 ft) tall statue of Shen Kuo sitting on a platform, along with centuries-old published copies of hisDream Pool Essaysin glass cabinets, one of which is from Japan.[171]At the garden estate there are also displayed marble banners, statues of Shen Kuo, and a model of an armillary sphere; a small museum gallery depicts Shen's various achievements.[170]

ThePurple Mountain ObservatoryinNanjingdiscovered a newasteroidin 1964 and named it after Shen Kuo (2027 Shen Guo).[172]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Pronunciation inMainland China

- ^Pronunciation inTaiwan

- ^See the articleSociety of the Song dynasty

- ^Refer to thePartisans and factions, reformers and conservativessection of the articleHistory of the Song dynasty.

- ^For more, seeArchitecture of the Song dynasty

- ^For deforestation due to the Song dynasty iron industry and efforts to curb it, refer toEconomy of the Song dynasty

- ^From his biography in theDictionary of Scientific Biography(New York 1970–1990)

Citations

[edit]- ^abcdYao (2003), 544.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 4, Part 2, 33.

- ^John Makeham (2008).China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed.Thames & Hudson. p. 239.ISBN978-0-500-25142-3.

- ^Bowman (2000), 599.

- ^abMohn (2003), 1.

- ^abcdefSivin (1995), III, 22.

- ^Embree (1997), 843.

- ^abcdeSivin (1995), III, 18.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 23–24.

- ^abBowman (2000), 105.

- ^abcdeSivin (1995), III, 1.

- ^abcdSivin (1995), III, 5.

- ^abcdefSivin (1995), III, 6.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 230–231.

- ^Steinhardt (1997), 316.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 1, 135.

- ^abcdefghijklmnSivin (1995), III, 9.

- ^abcnn' (2004), 19.

- ^nn(1993), 109.

- ^abHartman (1990), 22.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 3.

- ^abcdefghSivin (1995), III, 7.

- ^Anderson (2008), 202.

- ^Ebrey et al. (2006), 164.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 7, 126.

- ^Zhang (1986), 489.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 4–5.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 8.

- ^abLian (2001), 20.

- ^Lian (2001), 24.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 10.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 11.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 580–581.

- ^Crespigny (2007), 659.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 579–580.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 580.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 29.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 30–31.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 475.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 499.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 501.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 30.

- ^Cherniack (1994), 95–96.

- ^abcNeedham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 660.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 352.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, 141.

- ^abRuitenbeek (1996), 26.

- ^abChung (2004), 19.

- ^Ruitenbeek (1996), 26–27.

- ^Bielenstein (1986), 239.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 31.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 30–31, Footnote 27.

- ^Sung (1981), 12, 19, 20, 72.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 39.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 145.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 109.

- ^abcKatz (2007), 308.

- ^abRestivo (1992), 32.

- ^Bréard (2008).

- ^Katz (2007), 308–309.

- ^Katz (2007), 309.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 12, 14.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 14.

- ^Ebrey et al. (2006), 162.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 2, 473–475.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 15.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 139.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 97–98.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 98–99.

- ^abcSivin (1995), III, 34.

- ^abcSarkar, Salazar-Palma, Sengupta (2006), 21.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 98.

- ^abcSivin (1995), III, 21.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 252.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 249–250.

- ^abHsu (1988), 102.

- ^abElisseeff (2000), 296.

- ^abNeedham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 279.

- ^Fairbank & Goldman (1992), 33.

- ^Ebrey et al. (2006), 163.

- ^abcdefghnn(1986), 227.

- ^Rudolph (1963), 176.

- ^abcNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 574.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 573.

- ^Desmond (1975), 692–707.

- ^Rafferty (2012), 9.

- ^Schottenhammer (2012), 72.

- ^Salam (1984), 179–213.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 603–604.

- ^abcSivin (1995), III, 23.

- ^abcNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 618.

- ^abcdnn (2002), 15.

- ^abcdefNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 614.

- ^abcNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 604.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 468.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, p. 25.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 24.

- ^Sivin (1984), 534.

- ^Kim (2000), 171.

- ^abcdDong (2000), 72.

- ^abcdSivin (1995), III, 17.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 278.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 411.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 413–414.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 227.

- ^abcdefNeedham (1986), Volume 3, 415–416.

- ^Jin (1996), 431–432.

- ^Dong (2000), 71–72.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 16.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 19.

- ^Sivin (1995), II, 71–72.

- ^abcHenderson (1986), 128.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 18–19.

- ^abSivin (1995), II, 73.

- ^Sivin (1995), II, 72.

- ^abcdNeedham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 201.

- ^Gernet (1996), 335.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 202–203.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 27.

- ^Wu (1943), 211–212.

- ^Xu Yinong Moveable Type Books (Từ nhớ nông chữ in rời bổn)ISBN7-80643-795-9

- ^abcdNeedham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 203.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 206.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 205–206.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 208.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 217.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 211.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 1, 212.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 545.

- ^Hartwell (1966), 54.

- ^Menzies (1994), 24.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 7, 75–76.

- ^Deng (2005), 36.

- ^abSivin (1990), 170.

- ^Biderman & Scharfstein (1989), xvii.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 34–35.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 35.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 3, 482.

- ^Ebrey (1999), 148.

- ^Dong (2000), 69. (Professor Zhang Longqiao of the Chinese Department of Peking Teachers College, who popularized this account in Beijing'sGuang Ming Dailyon February 18, 1979, in an article called "Could It Be That A Visitor From Outer Space Visited China Long Ago?", states is "a clue that a flying craft from some other planet once landed somewhere nearYangzhouin China. ")

- ^Dong (2000), 69–70.

- ^Dong (2000), 70–71.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 4, 115.

- ^Stanley-Baker (1977), 23.

- ^Barnhart (1970), 25.

- ^Li (1965), 61.

- ^Barnhart (1970), 24.

- ^Li (1965), 37–38, Footnote 98.

- ^Li (1974), 149.

- ^Parker (1999), 175.

- ^Chen Dengyuan, cited in Sivin (1995), III, 44.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 44–45.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 44.

- ^Bodde (1991), 86.

- ^Sivin (1995), III, 45.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 46.

- ^abSivin (1995), III, 47.

- ^Needham (1986), Volume 1, 137.

- ^abcdeSivin (1995), III, 48.

- ^Hargett (1985), 67.

- ^Hargett (1985), 71.

- ^abcStock (1993), 94.

- ^Stock (1993), 108.

- ^nn(1986), 226–227.

- ^Gernet (1996), 338.

- ^Yao (2003), 545.

- ^abcdHuff (2003), 303.

- ^Sivin (1988), 59.

- ^abc Yuhang Cultural Network (October 2003).Shen Kuo's TombArchived2014-05-02 at theWayback MachineThe Yuhang District of Hangzhou Cultural Broadcasting Press and Publications Bureau. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

- ^abc Zhen gian g.gov (October 2006).Talking ParkArchived2007-07-07 at theWayback MachineThe Zhen gian g municipal government office. Retrieved on 2007-05-07.

- ^abc The Zhen gian g Foreign Experts Bureau (June 2002).Mengxi GardenArchived2007-09-29 at theWayback MachineThe Zhen gian g Foreign Experts Bureau. Retrieved on 2007-05-07.

- ^"2027 Shen Guo".IAU Minor Planet Center.Retrieved2018-10-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, James A. (2008). "'Treacherous Factions': Shifting Frontier Alliances in the Breakdown of Sino-Vietnamese Relations on the Eve of the 1075 Border War," inBattlefronts Real and Imagined: War, Border, and Identity in the Chinese Middle Period,191–226. Edited by Don J. Wyatt. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.ISBN978-1-4039-6084-9.

- Barnhart, Richard. "Marriage of the Lord of the River: A Lost Landscape by Tung Yüan,"Artibus Asiae. Supplementum(Volume 27, 1970): 3–5, 7, 9, 11–60.

- Biderman, Shlomo and Ben-Ami Scharfstein. (1989).Rationality in Question: On Eastern and Western Views of Rationality.Leiden: E.J. Brill.ISBN90-04-09212-9.

- Bielenstein, Hans. (1986). "Wang Mang, the Restoration of the Han Dynasty, and Later Han," inThe Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220,223–290. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-24327-0.

- Bodde, Derk(1991).Chinese Thought, Society, and Science: The Intellectual and Social Background of Science and Technology in Pre-modern China.Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.ISBN978-0-8248-1334-5

- Bowman, John S. (2000).Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture.New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bréard, Andrea(2008).A Summation Algorithm from 11th Century China. Possible Relations Between Structure and Argument.In: Beckmann, A., Dimitracopoulos, C., Löwe, B. (eds) Logic and Theory of Algorithms. CiE 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 5028. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-69407-6_8

- nn,(missing title). (2002). In Chan, Alan Kam-leung and Gregory K. Clancey, Hui-Chieh Loy (eds.)Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine.Singapore: Singapore University Press.ISBN9971-69-259-7

- Cherniack, Susan. "Book Culture and Textual Transmission in Sung China,"Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies(Volume 54, Number 1, 1994): 5–125.

- Chung, Anita. (2004).Drawing Boundaries: Architectural Images in Qing China.Manoa: University of Hawai'i Press.ISBN0-8248-2663-9.

- Crespigny, Rafe de. (2007).A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD).Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.ISBN90-04-15605-4.

- Deng, Yinke. (2005).Ancient Chinese Inventions.Translated by Wang Ping xing. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press.ISBN7-5085-0837-8.

- Desmond, Adrian."The Discovery of Marine Transgressions and the Explanation of Fossils in Antiquity,"American Journal of Science,1975, Volume 275: 692–707.

- Dong, Paul. (2000).China's Major Mysteries: Paranormal Phenomena and the Unexplained in the People's Republic.San Francisco: China Books and Periodicals, Inc.ISBN0-8351-2676-5.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, and James B. Palais (2006).East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.ISBN0-618-13384-4.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999).The Cambridge Illustrated History of China.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-43519-6(hardback);ISBN0-521-66991-X(paperback).

- Elisseeff, Vadime. (2000).The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce.New York: Berghahn Books.ISBN1-57181-222-9.

- Embree, Ainslie T.andCarol Gluck(1997).Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching.New York: An East Gate Book, M. E. Sharpe Inc.ISBN1-56324-265-6.

- Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992).China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition(2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.ISBN0-674-01828-1.

- nn,(missing title). (1986). in Fraser, Julius Thomas and Francis C. Haber (eds.).Time, Science, and Society in China and the West.Amherst:University of Massachusetts Press.ISBN0-87023-495-1.

- Gernet, Jacques. (1996).A History of Chinese Civilization.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-49781-7.

- Hargett, James M. "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960–1279),"Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews(CLEAR) (July 1985): 67–93.

- Hartman, Charles. "Poetry and Politics in 1079: The Crow Terrace Poetry Case of Su Shih,"Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews(Volume 12, 1990): 15–44.

- Hartwell, Robert (1966). "Markets, Technology, and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh-Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry".The Journal of Economic History.26:29–58.doi:10.1017/S0022050700061842.S2CID154556274.

- Henderson, John B. "Ch'ing Scholars' Views of Western Astronomy,"Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies(Volume 46, Number 1, 1986): 121–148.

- Hsu, Mei-ling. "Chinese Marine Cartography: Sea Charts of Pre-Modern China,"Imago Mundi(Volume 40, 1988): 96–112.

- Huff, Toby E. (2003).The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-52994-8.

- nn,(missing title), (1993). in Hymes, Robert P. and Conrad Schirokauer (eds.)Ordering the World: Approaches to State and Society in Sung Dynasty China.Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Jin, Zumeng. (1996)A Critique of ‘Zhang Heng’s Theory of a Spherical Earthin Fan, Dainian and Cohen, Robert Sonné (eds.).Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology.Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.ISBN0-7923-3463-9

- Katz, Victor J. (2007).The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook.Princeton: Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-11485-4.

- Kim, Yung Sik. (2000).The Natural Philosophy of Chu Hsi (1130–1200).DIANE Publishing.ISBN0-87169-235-X.

- Li, Chu-Tsing. "The Autumn Colors on the Ch'iao and Hua Mountains: A Landscape by Chao Meng-Fu,"Artibus Asiae(Volume 21, 1965): 4–7, 9–85, 87, 89–109.

- Li, Chu-Tsing. "A Thousand Peaks and Myriad Ravines: Chinese Paintings in the Charles A. Drenowatz Collection,"Artibus Asiae(Volume 30, 1974): I-XI, 1–5, 7–49, 51–79, 81–133, 135–161, 163–199, 201–217, 219–289, 291–301, 303–319, I-CV, CVII-CXIV.

- Lian, Xianda. "The Old Drunkard Who Finds Joy in His Own Joy -Elitist Ideas in Ouyang Xiu's Informal Writings,"Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews(Volume 23, 2001): 1–29.

- Menzies, Nicholas K. (1994).Forest and Land Management in Imperial China.New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc.ISBN0-312-10254-2.

- Mohn, Peter (2003).Magnetism in the Solid State: An Introduction.New York: Springer-Verlag Inc.ISBN3-540-43183-7.

- Needham, Joseph(1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations.Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth.Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics.Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics.Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing.Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic.Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986).Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1: Botany.Taipei, Caves Books Ltd.

- Parker, Joseph D. (1999). Zen Buddhist Landscape Arts of Early Muromachi Japan (1336–1573). Albany: State University of New York Press.ISBN0-7914-3909-7.

- Rafferty, John P. (2012).Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks.New York: Britannica Educational Publishing.ISBN9781615305445

- Restivo, Sal. (1992).Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries.Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.ISBN1-4020-0039-1.

- Rudolph, R.C. "Preliminary Notes on Sung Archaeology,"The Journal of Asian Studies(Volume 22, Number 2, 1963): 169–177.

- Ruitenbeek, Klaas. (1996).Carpentry & Building in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Fifteenth Century Carpenter's Manual Lu Ban Jing.Leiden: E.J. Brill.ISBN90-04-10529-8.

- Salam, Abdus (1987). "Islam and Science".Ideals and Realities — Selected Essays of Abdus Salam.pp. 179–213.doi:10.1142/9789814503204_0018.ISBN978-9971-5-0315-4.

- Sarkar, Tapan K., Magdalena Salazar-Palma, and Dipak L. Sengupta. (2006). "Development of the Theory of Light," inHistory of Wireless,20–28. Edited by Tapan K. Sarkar, Robert J. Mailloux,Arthur A. Oliner,Magdalena Salazar-Palma, and Dipak L. Sengupta. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc.ISBN0-471-78301-3.

- Schottenhammer, Angela. "The 'China Seas' in world history: A general outline of the role of Chinese and East Asian maritime space from its origins to c. 1800,"Journal of Marine and Island Cultures,(Volume 1, Issue 2, 2012): 63–86. ISSN 2212-6821.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imic.2012.11.002.

- Sivin, Nathan(1995, first publication 1975).Shen KuainScience in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections.Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Sivin, Nathan. (1984). "Why the Scientific Revolution Did Not Take Place in China—Or Didn't It?"inTransformation and Tradition in the Sciences: Essays in Honor of I. Bernard Cohen,531–555, ed. Everett Mendelsohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-52485-7.

- Sivin, Nathan. "Science and Medicine in Imperial China—The State of the Field,"The Journal of Asian Studies,Vol. 47, No. 1 (Feb., 1988): 41–90.

- Sivin, Nathan.Science and Medicine in Chinese History.(1990). in Ropp, Paul S. (ed.)Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese History.Berkeley: University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-06440-9

- Stanley-Baker, Joan. "The Development of Brush-Modes in Sung and Yüan,"Artibus Asiae(Volume 39, Number 1, 1977): 13–59.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (1997).Liao Architecture.Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Stock, Jonathan. "A Historical Account of the Chinese Two-Stringed Fiddle Erhu,"The Galpin Society Journal(Volume 46, 1993): 83–113.

- Sung, Tz’u, translated by Brian E. McKnight (1981).The Washing Away of Wrongs: Forensic Medicine in Thirteenth-Century China.Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.ISBN0-89264-800-7

- nn,(missing title). (2004). In Tao, Jie, Zheng Bijun and Shirley L. Mow. (eds.)Holding Up Half the Sky: Chinese Women Past, Present, and Future.New York: Feminist Press.ISBN1-55861-465-6.

- Wu, Kuang Ch'ing. "Ming Printing and Printers,"Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies(February 1943): 203–260.

- Yao, Xinzhong. (2003).RoutledgeCurzon Encyclopedia of Confucianism: Volume 2, O–Z.New York: Routledge.ISBN0-7007-1199-6.

- Zhang, Yunming (1986).Isis: The History of Science Society: Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. According to Sivin (1995), III, 49—historianNathan Sivin—Zhang's biography on Shen is of great importance as it contains the fullest and most accurate account of Shen Kuo's life.

External links

[edit]

- 1031 births

- 1095 deaths

- 11th-century antiquarians

- 11th-century agronomists

- 11th-century cartographers

- 11th-century Chinese astronomers

- 11th-century Chinese historians

- 11th-century Chinese mathematicians

- 11th-century Chinese musicians

- 11th-century Chinese philosophers

- 11th-century Chinese poets

- 11th-century Chinese scientists

- 11th-century diplomats

- 11th-century geographers

- 11th-century inventors

- 11th-century Taoists

- Agriculturalists

- Astronomical instrument makers

- Biologists from Zhe gian g

- Chemists from Zhe gian g

- Chinese agronomists

- Chinese anatomists

- Chinese antiquarians

- Chinese antiques experts

- Chinese archaeologists

- Chinese art critics

- Chinese cartographers

- Chinese civil engineers

- Chinese climatologists

- Chinese electrical engineers

- Chinese encyclopedists

- Chinese entomologists

- Chinese ethnographers

- Chinese geomorphologists