Book of Documents

This article mayrequirecleanupto meet Wikipedia'squality standards.The specific problem is:use of chinese-language text needs to be pared down or edited to conform withMOS:ZH.(November 2023) |

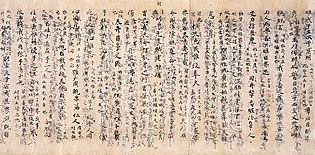

A page of an annotatedBook of Documentsmanuscript from the 7th century, held by theTokyo National Museum | |

| Author | Various; compilation traditionally attributed toConfucius |

|---|---|

| Original title | Thư*s-ta[a] |

| Language | Old Chinese |

| Subject | Compilation of rhetorical prose |

| Publication place | ZhouChina |

TheBook of Documents(Chinese:Thư kinh;pinyin:Shūjīng;Wade–Giles:Shu King), or theClassic of History,[b]is one of theFive Classicsof ancientChinese literature.It is a collection of rhetorical prose attributed to figures ofancient China,and served as the foundation of Chinesepolitical philosophyfor over two millennia.

TheBook of Documentswas the subject of one of China's oldest literary controversies, between proponents of different versions of the text. A version was preserved fromQin Shi Huang'sburning of books and burying of scholarsby scholarFu Sheng,in 29 chapters (piānThiên). This group of texts were referred to as "Modern Script" (jīnwénThể chữ Lệ), because they were written with the script in use at the beginning of the Western Han dynasty.

A longer version of theDocumentswas said to be discovered in the wall ofConfucius's family estate inQufuby his descendantKong Anguoin the late 2nd century BC. This new material was referred to as "Old Script" (gǔwénCổ văn), because they were written in the script that predated the standardization of Chinese script during the Qin. Compared to the Modern Script texts, the "Old Script" material had 16 more chapters. However, this seems to have been lost at the end of the EasternHan dynasty,while the Modern Script text enjoyed circulation, in particular inOuyang Gao'sstudy, called theOuyang Shangshu(Âu Dương thượng thư). This was the basis of studies byMa RongandZheng Xuanduring the Eastern Han.[2][3]

In 317 AD,Mei Zepresented to theEastern Jincourt a 58-chapter (59 if the preface is counted)Book of Documentsas Kong Anguo's version of the text. This version was accepted, despite the doubts of a few scholars, and later was canonized as part ofKong Yingda's project. It was only in the 17th century thatQing dynastyscholarYan Ruoqudemonstrated that the "Old Script" were actually fabrications "reconstructed" in the 3rd or 4th centuries AD.

In the transmitted edition, texts are grouped into four sections representing different eras: the legendary reign ofYu the Great,and theXia,ShangandZhoudynasties. The Zhou section accounts for over half the text. Some Modern Script chapters are among the earliest examples of Chinese prose, recording speeches from the early years of the Zhou dynasty in the late 11th century BC. Although the other three sections purport to record earlier material, most scholars believe that even the New Script chapters in these sections were composed later than those in the Zhou section, with chapters relating to the earliest periods being as recent as the 4th or 3rd centuries BC.[4][5]

Textual history[edit]

The history of the various versions of theDocumentsis particularly complex, and has been the subject of a long-running literary and philosophical controversy.

Early references[edit]

According to a later tradition, theBook of Documentswas compiled byConfucius(551–479 BC) as a selection from a much larger group of documents, with some of the remainder being included in theYi Zhou Shu.[6]However, the early history of both texts is obscure.[7]Beginning with Confucius, writers increasingly drew on theDocumentsto illustrate general principles, though it seems that several different versions were in use.[8]

Six citations to unnamed chapters of theDocumentsappear in theAnalects.While Confucius invoked the pre-dynastic emperorsYaoandShun,as well as figures from theXiaandShangdynasties, he complained of the lack of documentation prior to the Zhou. TheDocumentswere cited increasingly frequently in works through the 4th century BC, including in theMencius,MoziandZuo Zhuan.These authors favoured documents relating to Yao, Shun and the Xia dynasty, chapters now believed to have been written in theWarring States period.The chapters currently believed to be the oldest—mostly relating to the early Zhou—were little used by Warring States authors, perhaps due to the difficulty of the archaic language or a less familiar worldview.[9]Fewer than half the passages quoted by these authors are present in the received text.[10]Authors such asMenciusandXunzi,while quoting theDocuments,refused to accept it as genuine in its entirety. Their attitude contrasts with the reverence later shown to the text during the Han dynasty, when its compilation was attributed to Confucius.[11]

Han dynasty: Modern and Old Scripts[edit]

Many copies of the work were destroyed in theBurning of Booksduring theQin dynasty. Fu Shengreconstructed part of the work from hidden copies in the late 3rd to early 2nd century BC, at the start of the succeedingHan dynasty.The texts that he transmitted were known as the "Modern Script" (Thể chữ Lệjīn wén) because it was written in theclerical script.[12][13] It originally consisted of 29 chapters, but the "Great Speech" quá thề chapter was lost shortly afterwards and replaced by a new version.[14]The remaining 28 chapters were later expanded into 30 when Ouyang Gao divided the "Pangeng" chapter into three sections.[15]

During the reign ofEmperor Wu,renovations of the home of Confucius are said to have uncovered several manuscripts hidden within a wall, including a longer version of theDocuments. These texts were referred to as "Old Script" because they were written in the pre-Qinseal script.[13] They were transcribed into clerical script and interpreted by Confucius' descendantKong Anguo.[13] Han dynasty sources give contradictory accounts of the nature of this find.[16]According to the commonly repeated account of theBook of Han,the "Old Script" texts included the chapters preserved by Fu Sheng, another version of the "Great Speech" chapter and some 16 additional ones.[13] It is unclear what happened to these manuscripts. According to theBook of Han,Liu Xiangcollated the Old Script version against the three main "Modern Script" traditions, creating a version of theDocumentsthat included both groups. This was championed by his sonLiu Xin,[17] who requested in a letter to Emperor Ai the establishment of aboshiposition for its study.[18]But this did not happen. Most likely, this edition put together by the imperial librarians was lost in the chaos that ended the Western Han dynasty, and the later movement of the capital and imperial library.

A list of 100 chapter titles was also in circulation; many are mentioned in theRecords of the Grand Historian,but without quoting the text of the other chapters.[19]

Theshuwere designated one of theFive Classicswhen Confucian works made official byEmperor Wu of Han,andjīng('classic') was added to its name. The termShàngshū'venerated documents' was also used in the Eastern Han.[20] TheXiping Stone Classics,set up outside the imperial academy in 175–183 but since destroyed, included a Modern Script version of theDocuments.[21] Most Han dynasty scholars ignored the Old Script version, and it disappeared by the end of the dynasty.[19]

Claimed recovery of Old Script texts[edit]

A version of theDocumentsthat included the "Old Script" texts was allegedly rediscovered by the scholarMei Zeduring the 4th century, and presented to the imperial court of theEastern Jin.[21] His version consisted of the 31 modern script texts in 33 chapters, and 18 additional old script texts in 25 chapters, with a preface and commentary purportedly written by Kong Anguo.[22]This was presented asGuwen ShangshuCổ văn thượng thư, and was widely accepted. It was the basis of theShàngshū zhèngyì(Thượng thư chính nghĩa'Correct interpretation of theDocuments') published in 653 and made the official interpretation of theDocumentsby imperial decree. The oldest extant copy of the text, included in theKaicheng Stone Classics(833–837), contains all of these chapters.[21]

Since theSong dynasty,starting from Wu Yu (Ngô vực), many doubts had been expressed concerning the provenance of the allegedly rediscovered "Old Script" texts in Mei Ze's edition. In the 16th century, Mei Zhuo (Mai trạc) published a detailed argument that these chapters, as well as the preface and commentary, were forged in the 3rd century AD using material from other historical sources such as theZuo Commentaryand theRecords of the Grand Historian.Mei identified the sources from which the forger had cut and pasted text, and even suggestedHuangfu Mias a probable culprit. In the 17th century,Yan Ruoqu's unpublished but widely distributed manuscript entitledEvidential analysis of the Old Script Documents(Thượng thư cổ văn sơ chứng;Shàngshū gǔwén shūzhèng) convinced most scholars that the rediscovered Old Script texts were fabricated in the 3rd or 4th centuries.[23]

Modern discoveries[edit]

New light has been shed on theBook of Documentsby the recovery between 1993 and 2008 of caches oftexts written on bamboo slipsfrom tombs of thestate of ChuinJingmen, Hubei.[24]These texts are believed to date from the late Warring States period, around 300 BC, and thus predate the burning of the books during the Qin dynasty.[24]TheGuodian Chu Slipsand the Shanghai Museum corpus include quotations of previously unknown passages of the work.[24][25]TheTsinghua Bamboo Slipsincludes a version of the transmitted text "Golden Coffer", with minor textual differences, as well as several documents in the same style that are not included in the received text. The collection also includes two documents that the editors considered to be versions of the Old Script texts "Common Possession of Pure Virtue" and "Command toFu Yue".[26]Other authors have challenged these straightforward identifications.[27][28]

Contents[edit]

In the orthodox arrangement, the work consists of 58 chapters, each with a brief preface traditionally attributed to Confucius, and also includes a preface and commentary, both purportedly by Kong Anguo. An alternative organization, first used byWu Cheng,includes only the Modern Script chapters, with the chapter prefaces collected together, but omitting the Kong preface and commentary. In addition, several chapters are divided into two or three parts in the orthodox form.[22]

Nature of the chapters[edit]

With the exception of a few chapters of late date, the chapters are represented as records of formal speeches by kings or other important figures.[29][30] Most of these speeches are of one of five types, indicated by their titles:[31]

- Consultations (Mômó) between the king and his ministers (2 chapters),

- Instructions (Huấnxùn) to the king from his ministers (1 chapter),

- Announcements (Cáogào) by the king to his people (8 chapters),

- Declarations (Thềshì) by a ruler on the occasion of a battle (6 chapters), and

- Commands (Mệnhmìng) by the king to a specific vassal (7 chapters).

Classical Chinese tradition lists six types ofShu,beginning withdianĐiển,Canons (2 chapters in the Modern corpus).

According toSu Shi(1037–1101), it is possible to single out Eight Announcements of the early Zhou, directed to the Shang people. Their titles only partially correspond to the modern chapters marked asgao(apart from the nos. 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 that mention the genre, Su Shi names nos. 16 "Zi cai", 19 "Duo shi" and 22 "Duo fang" ).

As pointed out byChen Mengjia(1911–1966), announcements and commands are similar, but differ in that commands usually include granting of valuable objects, land or servants to their recipients.

Guo ChangbaoQuá thường bảoclaims that the graph for announcement (Cáo), known since theOracle bone script,also appears on two bronze vessels (He zunandShi Zhi guiSử [ thần + lưỡi ] âu), as well as in the "six genres"Sáu từof theZhou li[32][clarification needed]

In many cases a speech is introduced with the phraseWáng ruò yuē(Vương nếu rằng'The king seemingly said'), which also appears on commemorativebronze inscriptionsfrom the Western Zhou period, but not in other received texts. Scholars interpret this as meaning that the original documents were prepared scripts of speeches, to be read out by an official on behalf of the king.[33][34]

Traditional organization[edit]

The chapters are grouped into four sections representing different eras: the semi-mythical reign ofYu the Great,and the three ancient dynasties of theXia,ShangandZhou. The first two sections – on Yu the Great and the Xia dynasty – contain two chapters each in the Modern Script version, and though they purport to record the earliest material in theDocuments,from the 2nd millennium BC, most scholars believe they were written during theWarring States period. The Shang dynasty section contains five chapters, of which the first two – the "Speech ofKing Tang"and"Pan Geng"– recount the conquest of the Xia by the Shang and their leadership's migration to a new capital (now identified asAnyang). The bulk of the Zhou dynasty section concerns the reign ofKing Cheng of Zhou(r.c. 1040–1006 BC) and the king's uncles, theDuke of ZhouandDuke of Shao. The last four Modern Script chapters relate to the later Western Zhou and early Spring and Autumn periods.[35]

| Part | New Text |

Orthodox chapter |

Title | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ngu thư Yu [Shun] |

1 | 1 | Nghiêu điển | Yáo diǎn | Canon ofYao |

| 2 | Thuấn điển | Shùn diǎn | Canon ofShun | ||

| 3 | Đại Vũ mô | Dà Yǔ mó | Counsels ofGreat Yu | ||

| 2 | 4 | Cao đào mô | Gāo Yáo mó | Counsels ofGao Yao | |

| 5 | Ích kê | Yì jì | Yi and Ji | ||

| Hạ thư Xia |

3 | 6 | Vũ cống | Yǔ gòng | Tribute of [Great] Yu |

| 4 | 7 | Cam thề | Gān shì | Speech at [the Battle of] Gan | |

| 8 | Ngũ tử chi ca | Wǔ zǐ zhī gē | Songs of the Five Sons | ||

| 9 | Dận chinh | Yìn zhēng | Punitive Expedition on [King Zhongkang of] Yin | ||

| Thương thư Shang |

5 | 10 | Canh thề | Tāng shì | Speech ofTang |

| 11 | Trọng hủy chi cáo | Zhònghuī zhī gào | Announcement of Zhonghui | ||

| 12 | Canh cáo | Tāng gào | Announcement of Tang | ||

| 13 | Y huấn | Yī xùn | Instructions ofYi [Yin] | ||

| 14–16 | Quá giáp | Tài jiǎ | Great Oath parts 1, 2 & 3 | ||

| 17 | Hàm có một đức | Xián yǒu yī dé | Common Possession of Pure Virtue | ||

| 6 | 18–20 | Bàn canh | Pán Gēng | Pan Gengparts 1, 2 & 3 | |

| 21–23 | Nói mệnh | Yuè mìng | Charge toYueparts 1, 2 & 3 | ||

| 7 | 24 | Cao tông dung ngày | Gāozōng róng rì | Day of the Supplementary Sacrifice ofKing Gaozong | |

| 8 | 25 | Tây bá kham lê | Xībó kān lí | Chief of the West [King Wen]'s Conquest of [the State of] Li | |

| 9 | 26 | Hơi tử | Wēizǐ | [Prince] Weizi | |

| Chu thư Zhou |

27–29 | Thái thề | Tài shì | Great Speech parts 1, 2 & 3 | |

| 10 | 30 | Mục thề | Mù shì | Speech atMuye | |

| 31 | Võ thành | Wǔ chéng | Successful Completion of the War [on Shang] | ||

| 11 | 32 | Hồng phạm | Hóng fàn | Great Plan [of Jizi] | |

| 33 | Lữ ngao | Lǚ áo | Hounds of [the Western Tribesmen] Lü | ||

| 12 | 34 | Kim đằng | Jīn téng | Golden Coffer [of Zhou Gong] | |

| 13 | 35 | Đại cáo | Dà gào | Great Announcement | |

| 36 | Hơi tử chi mệnh | Wēizǐ zhī mìng | Charge to Prince Weizi | ||

| 14 | 37 | Khang cáo | Kāng gào | Announcement toKang | |

| 15 | 38 | Rượu cáo | Jiǔ gào | Announcement about Drunkenness | |

| 16 | 39 | Tử tài | Zǐ cái | Timber of Rottlera | |

| 17 | 40 | Triệu cáo | Shào gào | Announcement of Duke Shao | |

| 18 | 41 | Lạc cáo | Luò gào | Announcement concerningLuoyang | |

| 19 | 42 | Nhiều sĩ | Duō shì | Numerous Officers | |

| 20 | 43 | Vô dật | Wú yì | Against Luxurious Ease | |

| 21 | 44 | Quân thích | Jūn shì | Lord Shi [Duke Shao] | |

| 45 | Thái Trọng chi mệnh | Cài Zhòng zhī mìng | Charge to Cai Zhong | ||

| 22 | 46 | Nhiều mặt | Duō fāng | Numerous Regions | |

| 23 | 47 | Lập chính | Lì zhèng | Establishment of Government | |

| 48 | Chu quan | Zhōu guān | Officers of Zhou | ||

| 49 | Quân trần | Jūn chén | Lord Chen | ||

| 24 | 50 | Cố mệnh | Gù mìng | Testamentary Charge | |

| 51 | Khang Vương chi cáo | Kāng wáng zhī gào | Proclamation of King Kang | ||

| 52 | Tận số | Bì mìng | Charge to the [Duke of] Bi | ||

| 53 | Quân nha | Jūn Yá | Lord Ya | ||

| 54 | Quýnh mệnh | Jiǒng mìng | Charge to Jiong | ||

| 25 | 55 | Lữ hình | Lǚ xíng | [Marquis] Lü on Punishments | |

| 26 | 56 | Văn hầu chi mệnh | Wén hóu zhī mìng | Charge toDuke Wen of Jin | |

| 27 | 57 | Phí thề | Fèi shì | Speech at [the Battle of] Fei | |

| 28 | 58 | Tần thề | Qín shì | Speech ofDuke Mu of Qin | |

Dating of the Modern Script chapters[edit]

Not all of the Modern Script chapters are believed to be contemporaneous with the events they describe, which range from the legendary emperorsYaoandShunto early in theSpring and Autumn period.[36] Six of these chapters concern figures prior to the first evidence of writing, theoracle bonesdating from the reign of theLate ShangkingWu Ding. Moreover, the chapters dealing with the earliest periods are the closest in language and focus to classical works of theWarring States period.[37]

The five announcements in the Documents of Zhou feature the most archaic language, closely resembling inscriptions found on Western Zhou bronzes in both grammar and vocabulary. They are considered by most scholars to record speeches ofKing Cheng of Zhou,as well as theDuke of ZhouandDuke of Shao,uncles of King Cheng who were key figures during his reign (late 11th century BC).[38][39]They provide insight into the politics and ideology of the period, including the doctrine of theMandate of Heaven,explaining how the once-virtuous Xia had become corrupt and were replaced by the virtuous Shang, who went through a similar cycle ending in their replacement by the Zhou.[40] The "Timber of Rottlera", "Numerous Officers", "Against Luxurious Ease" and "Numerous Regions" chapters are believed to have been written somewhat later, in the late Western Zhou period.[39] A minority of scholars, pointing to differences in language between the announcements and Zhou bronzes, argue that all of these chapters are products of a commemorative tradition in the late Western Zhou or early Spring and Autumn periods.[41][42]

Chapters dealing with the late Shang and the transition to Zhou use less archaic language. They are believed to have been modelled on the earlier speeches by writers in the Spring and Autumn period, a time of renewed interest in politics and dynastic decline.[39][4] The later chapters of the Zhou section are also believed to have been written around this time.[43] The "Gaozong Rongri" chapter comprises only 82 characters, and its interpretation was already disputed in Western Han commentaries. Pointing to the similarity of its title to formulas found in the Anyangoracle bone inscriptions,David Nivisonproposed that the chapter was written or recorded by a collateral descendant ofWu Dingin the late Shang period some time after 1140 BC.[44]

The "Pan Geng" chapter (later divided into three parts) seems to be intermediate in style between this group and the next.[45]It is the longest speech in theDocuments,and is unusual in its extensive use of analogy.[46]Scholars since the Tang dynasty have noted the difficult language of the "Pan Geng" and the Zhou Announcement chapters.[c]Citing the archaic language and worldview, Chinese scholars have argued for a Shang dynasty provenance for the "Pan Geng" chapters, with considerable editing and replacement of the vocabulary by Zhou dynasty authors accounting for the difference in language from Shang inscriptions.[47]

The chapters dealing with the legendary emperors, the Xia dynasty and the transition to Shang are very similar in language to such classics as theMencius(late 4th century BC). They present idealized rulers, with the earlier political concerns subordinate to moral and cosmological theory, and are believed to be the products of philosophical schools of the late Warring States period.[4][45] Some chapters, particularly the "Tribute of Yu", may be as late as theQin dynasty.[5][48]

Influence in the West[edit]

When Jesuit scholars prepared the first translations of Chinese Classics into Latin, they called theDocumentsthe "Book of Kings", making a parallel with theBooks of Kingsin theOld Testament.They sawShang Dias the equivalent of the Christian God, and used passages from theDocumentsin their commentaries on other works.[49]

Notable translations[edit]

- Gaubil, Antoine(1770).Le Chou-king, un des livres sacrés des Chinois, qui renferme les fondements de leur ancienne histoire, les principes de leur gouvernement & de leur morale; ouvrage recueilli par Confucius[The Shūjīng, one of the Sacred Books of the Chinese, which contains the Foundations of their Ancient History, the Principles of their Government and their Morality; Material collected by Confucius] (in French). Paris: N. M. Tillard.

- Medhurst, W. H.(1846).Ancient China. The Shoo King or the Historical Classic.Shanghai: The Mission Press.

- Legge, James(1865).The Chinese Classics, volume III: the Shoo King or the Book of Historical Documents.London: Trubner.;rpt. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1960. (Full Chinese text with English translation using Legge's own romanization system, with extensive background and annotations.)

- Legge, James (1879).The Shû king; The religious portions of the Shih king; The Hsiâo king.Sacred Books of the East.Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Includes a minor revision of Legge's translation.

- Couvreur, Séraphin(1897).Chou King, Les Annales de la Chine[Shujing, the Annals of China] (in French). Hokkien: Mission Catholique.Reprinted (1999), Paris: You Feng.

- Karlgren, Bernhard(1950)."The Book of Documents".Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.22:1–81.(Modern Script chapters only) Reprinted as a separate volume by Elanders in 1950.

- Katō, JōkenThêm đằng thường hiền(1964).Shin kobun Shōsho shūshakuThật cổ văn thượng thư tập 釈[Authentic 'Old Text' Shàngshū, with Collected Commentary] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Meiji shoin.

- (in Mandarin Chinese)Qu, WanliKhuất vạn dặm(1969).Shàngshū jīnzhù jīnyìThượng thư nay chú kim dịch[The Book of Documents, with Modern Annotations and Translation]. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan.

- Waltham, Clae (1971).Shu ching: Book of History. A Modernized Edition of the Translation of James Legge.Chicago: Henry Regnery.

- Ikeda, SuitoshiTrì điền mạt lợi(1976).ShōshoThượng thư[Shàngshū] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shūeisha.

- Palmer, Martin; Ramsay, Jay; Finlay, Victoria (2014).The Most Venerable Book (Shang Shu) also known as the Shu Jing (The Classic of Chronicles).London: Penguin Books.

Notes[edit]

- ^The*k-lˤeng(jīngKinh) appellation would not have been used until theHan dynasty,after the coreOld Chineseperiod.

- ^Or simply as theShujingorShangshu(Thượng thư;Shàngshū;'Venerated Documents')

- ^Han Yuused the idiomTrúc trắc(roughly meaning 'unflowing' and 'difficult to say') to describe the Zhou 'Announcements' and the Yin (Shang) 'Pan Geng'.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Baxter & Sagart (2014),pp. 327–378.

- ^Hou Hanshu Hậu Hán Thư.Taipei: Dingwen shuju. 1981. p. 79.2556.

- ^Liu Qiyu Lưu khởi 釪 (2018).Shangshu xue shi thượng thư học sử(2nd ed.). Zhonghua Shuju Trung Hoa thư cục. p. 7.

- ^abcLewis (1999),p. 105.

- ^abNylan (2001),pp. 134, 158.

- ^Allan (2012),pp. 548–549, 551.

- ^Allan (2012),p. 550.

- ^Nylan (2001),p. 127.

- ^Lewis (1999),pp. 105–108.

- ^Schaberg (2001),p. 78.

- ^Nylan (2001),pp. 127–128.

- ^Nylan (2001),p. 130.

- ^abcdShaughnessy (1993),p. 381.

- ^Nylan (1995),p. 26.

- ^Liu Qiyü Lưu khởi đinh. (1996).Shangshu xue shi thượng thư học sử.Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Trung Hoa thư cục. p. 153.

- ^Nylan (1995),pp. 28–36.

- ^Nylan (1995),p. 48.

- ^Hanshu Hán Thư.pp. 36.1967–1970.

- ^abBrooks (2011),p. 87.

- ^Wilkinson (2000),pp. 475–477.

- ^abcShaughnessy (1993),p. 383.

- ^abShaughnessy (1993),pp. 376–377.

- ^Elman (1983),pp. 206–213.

- ^abcLiao (2001).

- ^Shaughnessy (2006),pp. 56–58.

- ^"First Research Results on Warring States Bamboo Strips Collected by Tsinghua University Released".Tsinghua University News.Tsinghua University.May 26, 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-25.

- ^Li Rui Lý duệ (2013). "Thanh Hoa giản 《 phó nói chi mệnh 》 nghiên cứu".Shenzhen Daxue Xuebao. Shehui Kexueban. Thâm Quyến đại học học báo ( nhân văn khoa học xã hội bản ) Journal of Shenzhen University (Humanities & Social Sciences).30(6): 68–72.

- ^Edward L. Shaughnessy (2020). "A Possible Lost Classic: The *She Ming, or *Command to She".T'oung Pao.106.3–4: 266–308.

- ^Allan (2011),p. 3.

- ^Allan (2012),p. 552.

- ^Shaughnessy (1993),p. 377.

- ^Luận 5 thượng thư 6 cáo thể văn hóa bối cảnh

- ^Allan (2011),pp. 3–5.

- ^Allan (2012),pp. 552–556.

- ^Shaughnessy (1993),pp. 378–380.

- ^Shaughnessy (1993),pp. 377–380.

- ^Nylan (2001),pp. 133–135.

- ^Shaughnessy (1999),p. 294.

- ^abcNylan (2001),p. 133.

- ^Shaughnessy (1999),pp. 294–295.

- ^Kern (2009),pp. 146, 182–188.

- ^Vogelsang (2002),pp. 196–197.

- ^Shaughnessy (1993),p. 380.

- ^Nivison (2018),pp. 22–23, 27–28.

- ^abNylan (2001),p. 134.

- ^Shih (2013),pp. 818–819.

- ^Phạm văn lan: "《 bàn canh 》 tam thiên là không thể hoài nghi thương triều di văn ( thiên trung khả năng có huấn hỗ sửa tự )"

- ^Shaughnessy (1993),p. 378.

- ^Meynard, Thierry (2015).The Jesuit Reading of Confucius: The First Complete Translation of the Lunyu (1687) Published in the West.Leiden, Boston: Brill. p. 47.ISBN978-90-04-28977-2.

Works cited[edit]

- Allan, Sarah(2011),"What is ashu thư?"(PDF),EASCM Newsletter(4): 1–5.

- ——— (2012), "OnShuThư(Documents) and the origin of theShang shuThượng thư(Ancient Documents) in light of recently discovered bamboo slip manuscripts ",Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies,75(3): 547–557,doi:10.1017/S0041977X12000547.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014).Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction.Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-994537-5.

- Brooks, E. Bruce (2011),"The Shu"(PDF),Warring States Papers,2:87–90.[dead link]

- Elman, Benjamin A. (1983),"Philosophy (i-li) versus philology (k'ao-cheng)—thejen-hsin Tao-hsindebate "(PDF),T'oung Pao,69(4): 175–222,doi:10.1163/156853283x00081,JSTOR4528296.

- Kern, Martin (2009),"Bronze inscriptions, theShijingand theShangshu:the evolution of the ancestral sacrifice during the Western Zhou "(PDF),in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (eds.),Early Chinese Religion, Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC to 220 AD),Leiden: Brill, pp. 143–200,ISBN978-90-04-16835-0.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1999),Writing and authority in early China,SUNY Press,ISBN978-0-7914-4114-5.

- Liao, Mingchun (2001),A Preliminary Study on the Newly-unearthed Bamboo Inscriptions of the Chu Kingdom: An Investigation of the Materials from and about the Shangshu in the Guodian Chu Slips(in Chinese), Taipei: Taiwan Guji Publishing Co.,ISBN957-0414-59-6.

- Nivison, David S.(2018) [1984], "The King and the Bird: a Possible Genuine Shang Literary Text and Its Echoes in Later Philosophy and Religion", in Schwartz, Adam C. (ed.),The Nivison Annals: Selected Works of David S. Nivison on Early Chinese Chronology, Astronomy, and Historiography,Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 22–28,doi:10.1515/9781501505393-003,ISBN978-1-5015-0539-3.

- Nylan, Michael(1995), "TheKu WenDocumentsin Han Times ",T'oung Pao,81(1/3): 25–50,doi:10.1163/156853295x00024,JSTOR4528653.

- ——— (2001),The Five "Confucian" Classics,Yale University Press,ISBN978-0-300-08185-5.

- Schaberg, David (2001),A patterned past: form and thought in early Chinese historiography,Harvard Univ Asia Center,ISBN978-0-674-00861-8.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L.(1993). "Shang shuThượng thư".In Loewe, Michael (ed.).Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide.Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 376–389.ISBN978-1-55729-043-4.

- ——— (1999), "Western Zhou history", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.),The Cambridge History of Ancient China,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 292–351,ISBN978-0-521-47030-8.

- ——— (2006),Rewriting early Chinese texts,SUNY Press,ISBN978-0-7914-6643-8.

- Shih, Hsiang-lin (2013), "Shang shuThượng thư(Hallowed writings of antiquity) ", in Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.),Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol. 2): A Reference Guide, Part Two Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 4 China,BRILL, pp. 814–830,ISBN978-90-04-20164-4.

- Vogelsang, Kai (2002), "Inscriptions and proclamations: on the authenticity of the 'gao' chapters in theBook of Documents",Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities,74:138–209.

- Wilkinson, Endymion(2000),Chinese history: a manual(2nd ed.), Harvard Univ Asia Center,ISBN978-0-674-00249-4.

External links[edit]

- 《 thượng thư 》–Shang Shuat theChinese Text Project,including both the Chinese text and Legge's English translation (emended to employ pinyin)

- Shangshuat the Database of Religious History.

- Selections from Legge'sShu Jing(also emended)

- Annotated Edition ofThe Book of Documents

- Book of Documents《 thượng thư 》Chinese text with matching English vocabulary at chinesenotes