Shuttle–Mirprogram

| Программа «Мир» — «Шаттл» | |

| |

| Program overview | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Organization | |

| Status | Completed |

| Program history | |

| First flight | February 3, 1994 (STS-60) |

| Last flight | June 2, 1998 (STS-91) |

| Launch site(s) | |

| Vehicle information | |

| Crewed vehicle(s) | |

| Part ofa serieson the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

| Part ofa seriesof articles on the |

| Soviet space program |

|---|

TheShuttle–Mirprogramwas a collaborative 11-mission space program between Russia and the United States that involved AmericanSpace Shuttlesvisiting the Russianspace stationMir,Russian cosmonauts flying on the Shuttle, and an American astronaut flying aboard aSoyuz spacecraftto engage in long-duration expeditions aboardMir.

The project, sometimes called "Phase One", was intended to allow the United States to learn from Russian experience with long-duration spaceflight and to foster a spirit of cooperation between the two nations and theirspace agencies,the USNational Aeronautics and Space Administration(NASA) and theRussian Federal Space Agency(Roscosmos). The project helped to prepare the way for further cooperative space ventures; specifically, "Phase Two" of the joint project, the construction of theInternational Space Station(ISS). The program was announced in 1993, the first mission started in 1994 and the project continued until its scheduled completion in 1998. Eleven Space Shuttle missions, a joint Soyuz flight and almost 1000 cumulative days in space for American astronauts occurred over the course of seven long-duration expeditions. In addition to Space Shuttle launches toMirthe United States also fully funded and equipped with scientific equipment theSpektrmodule (launched in 1995) and thePrirodamodule (launched in 1996), making them de facto U.S. modules during the duration of the Shuttle-Mirprogram.[1]

During the four-year program, many firsts inspaceflightwere achieved by the two nations, including the first American astronaut to launch aboard a Soyuz spacecraft, the largestspacecraftever to have been assembled at that time in history, and the first Americanspacewalkusing a RussianOrlan spacesuit.

The program was marred by various concerns, notably the safety ofMirfollowing a fire and a collision, financial issues with the cash-strapped Russian space program and worries from astronauts about the attitudes of the program administrators. Nevertheless, a large amount of science, expertise in space station construction and knowledge in working in a cooperative space venture was gained from the combined operations, allowing the construction of the ISS to proceed much more smoothly than would have otherwise been the case.

Background[edit]

The origins of the Shuttle–Mirprogram can be traced back to the 1975Apollo–Soyuz Test Project,that resulted in a joint US/Soviet mission during thedétenteperiod of theCold Warand the docking between a US Apollo spacecraft and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft. This was followed by the talks betweenNASAandIntercosmosin the 1970s about a "Shuttle–Salyut"program to flySpace Shuttlemissions to aSalyutspace station,with later talks in the 1980s even considering flights of the future Soviet shuttles from theBuran programmeto a future US space station – this "Shuttle–Salyut"program never materialized however during the existence of the Soviet Intercosmos program.[2]

This changed after theDissolution of the Soviet Union:the end of Cold War andSpace Raceresulted in funding for the US modular space station (originally namedFreedom), which was planned since the early 1980s, being slashed.[3] Similar budgetary difficulties were being faced by other nations with space station projects, prompting American government officials to start negotiations with partners in Europe, Russia, Japan, and Canada in the early 1990s to begin a collaborative, multi-national, space station project.[3] In theRussian Federation,as the successor to much of theSoviet Unionand its space program, the deteriorating economic situation in thepost-Soviet economic chaosled to growing financial problems of the now Russian space station program. The construction of theMir-2space station as a replacement for the agingMirbecame illusionary, though only after its base block, DOS-8, had been built.[3]These developments resulted in bringing the former adversaries together with the Shuttle–MirProgram, which would pave the way to theInternational Space Station,a joint project with several international partners.[4]

In June 1992,American PresidentGeorge H. W. BushandRussian presidentBoris Yeltsinagreed to co-operate onspace explorationby signing theAgreement between the United States of America and the Russian Federation Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes.This agreement called for setting up a short, joint space project, during which one Americanastronautwould board the Russian space stationMirand two Russiancosmonautswould board a Space Shuttle.[3]

In September 1993, AmericanVice-PresidentAl Gore Jr.,and Russian Prime MinisterViktor Chernomyrdinannounced plans for a new space station, which eventually became the International Space Station.[5]They also agreed, in preparation for this new project, that the United States would be heavily involved in theMirproject in the years ahead, under the code name "Phase One" (the construction of the ISS being "Phase Two" ).[6]

The first Space Shuttle flight toMirwas a rendezvous mission without docking onSTS-63.This was followed during the course of the project by nine Shuttle–Mirdocking missions, fromSTS-71toSTS-91.The Shuttle rotated crews and delivered supplies, and one mission,STS-74,carried a docking module and a pair of solar arrays toMir.Various scientific experiments were also conducted, both on shuttle flights and long-term aboard the station. The project also saw the launch of two new modules,SpektrandPriroda,toMir,which were used by American astronauts as living quarters and laboratories to conduct the majority of their science aboard the station. These missions allowed NASA and Roscosmos to learn a great deal about how best to work with international partners in space and how to minimize the risks associated with assembling a large space station in orbit, as would have to be done with the ISS.[7][8]

The project also served as a political ruse on the part of the American government, providing a diplomatic channel for NASA to take part in the funding of the cripplingly under-funded Russian space program. This in turn allowed the newly fledgedRussian governmentto keepMiroperating, in addition to the Russian space program as a whole, ensuring the Russian government remained friendly towards the United States.[9][10]

Increments[edit]

In addition to the flights of the Shuttle toMir,Phase One also featured seven "Increments" aboard the station, long-duration flights aboardMirby American astronauts. The seven astronauts who took part in the Increments,Norman Thagard,Shannon Lucid,John Blaha,Jerry Linenger,Michael Foale,David WolfandAndrew Thomas,were each flown in turn toStar City,Russia,to undergo training in various aspects of the operation ofMirand theSoyuz spacecraftused for transport to and from the Station. The astronauts also received practice in carrying outspacewalksoutsideMirand lessons in theRussian language,which would be used throughout their missions to talk with the other cosmonauts aboard the station and Mission Control in Russia, theTsUP.[10]

During their expeditions aboardMir,the astronauts carried out various experiments, including growth of crops and crystals, and took hundreds of photographs of theEarth.They also assisted in the maintenance and repair of the aging station, following various incidents with fires, collisions, power losses, uncontrolled spins and toxic leaks. In all, the American astronauts would spend almost a thousand days aboardMir,allowing NASA to learn a great deal about long-duration spaceflight, particularly in the areas of astronaut psychology and how best to arrange experiment schedules for crews aboard space stations.[9][10]

Mir[edit]

Mirwas constructed between 1986 and 1996 and was the world's first modular space station. It was the first consistently inhabited long-termresearch stationin space, and previously held the record for longest continuous human presence in space, at eight days short of ten years.Mir'spurpose was to provide a large and habitable scientific laboratory in space, and, through a number of collaborations, includingIntercosmosand Shuttle–Mir,was made internationally accessible to cosmonauts and astronauts of many different countries. The station existed until March 23, 2001, at which point it was deliberately deorbited, and broke apart during atmospheric re-entry.[3]

Mirwas based upon theSalyutseries of space stations previously launched by theSoviet Union(seven Salyut space stations had been launched since 1971), and was mainly serviced by Russian-crewedSoyuz spacecraftandProgresscargo ships. TheBuranspace shuttle was anticipated to visitMir,but its program was canceled after its first uncrewed spaceflight. Visiting US Space Shuttles used anAndrogynous Peripheral Attach Systemdocking collar originally designed for Buran, mounted on a bracket originally designed for use with the AmericanSpace Station Freedom.[3]

With the Space Shuttle docked toMir,the temporary enlargements of living and working areas amounted to a complex that was the world's largestspacecraftat that time, with a combined mass of 250metric tons(250long tons;280short tons).[3][11]

Space Shuttle[edit]

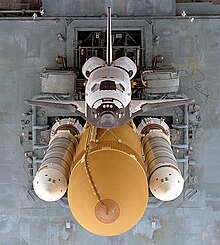

The Space Shuttle was a partiallyreusablelow Earth orbitalspacecraftsystem that was operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S.National Aeronautics and Space Administration(NASA) as part of theSpace Shuttle program.Its official program name wasSpace Transportation System (STS),taken from a 1969 plan fora system of reusable spacecraftof which it was the only item funded for development.[12]The first of four orbital test flights occurred in 1981, leading to operational flights beginning in 1982. In addition to the prototype, whose completion was cancelled, five complete Shuttle systems were built and used on a total of 135 missions from 1981 to 2011, launched from theKennedy Space Center(KSC) in Florida. The Shuttle fleet's total mission time was 1322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds.[13]

The Space Shuttle carried large payloads to various orbits, and, during the Shuttle–Mirand ISS programs, provided crew rotation and carried various supplies, modules and pieces of equipment to the stations. Each Shuttle was designed for a projected lifespan of 100 launches or 10 years' operational life.[14][15]

Nine docking missions were flown toMir,from 1995 to 1997 during "Phase One": Space ShuttleAtlantisdocked seven times toMir,withDiscoveryandEndeavoureach flying one docking mission toMir.As Space ShuttleColumbiawas the oldest and heaviest of the fleet, it was not suited for efficient operations atMir's(and later theISS's) 51.6-degree inclination –Columbiawas therefore not retrofitted with the necessary external airlock and Orbital Docking System, and never flew to a space station.[16][17][18]

Timeline[edit]

New cooperation begins (1994)[edit]

Phase One of the Shuttle–Mirprogram began on February 3, 1994, with the launch ofSpace ShuttleDiscoveryon its 18th mission,STS-60.The eight-day mission was the first shuttle flight of that year, the first flight of a Russiancosmonaut,Sergei Krikalev,aboard the American shuttle, and marked the start of increased cooperation in space for the two nations, 37 years after theSpace Racebegan.[19]Part of aninternational agreementon human space flight, the mission was the second flight of theSpacehabpressurized module and marked the hundredth "Getaway Special"payload to fly in space. The primary payload for the mission was theWake Shield Facility(or WSF), a device designed to generate new semiconductor films for advanced electronics. The WSF was flown at the end ofDiscovery'srobotic arm over the course of the flight. During the mission, the astronauts aboardDiscoveryalso carried out various experiments aboard theSpacehabmodule in the Orbiter's payload bay, and took part in a live bi-directional audio and downlink video hookup between themselves and the three cosmonauts on boardMir,Valeri Polyakov,Viktor AfanasyevandYury Usachev(flyingMirexpeditions LD-4 and EO-15).[16][20][21]

America arrives atMir(1995)[edit]

1995 began with the launch of the Space ShuttleDiscoveryon February 3. Discovery's mission,STS-63,was the second Space Shuttle flight in the program and the first flight of the shuttle with a female pilot,Eileen Collins.Referred to as the "near-Mir"mission, the eight-day flight saw the first rendezvous of a Space Shuttle withMir,as Russian cosmonautVladimir Titovand the rest ofDiscovery'screw approached within 37 feet (11 m) ofMir.Following the rendezvous, Collins performed a flyaround of the station. The mission, a dress rehearsal for the first docked mission in the program,STS-71,also carried out testing of various techniques and pieces of equipment that would be used during the docking missions that followed.[20][22][23]

Five weeks afterDiscovery'sflight, the March 14 launch ofSoyuz TM-21carried expedition EO-18 toMir.The crew consisted of cosmonautsVladimir DezhurovandGennady Strekalovand NASA astronautNorman Thagard,who became the first American to fly into space aboard theSoyuz spacecraft.During the course of their 115-day expedition, theSpektrscience module (which served as living and working space for American astronauts) was launched aboard aProton rocketand docked toMir.Spektr carried more than 1,500 pounds (680 kg) of research equipment from America and other nations. The expedition's crew returned to Earth aboardSpace ShuttleAtlantisfollowing the first Shuttle–Mirdocking during missionSTS-71.[3][9][24]

The primary objectives of STS-71, launched on June 27, called for the Space ShuttleAtlantisto rendezvous and perform the first docking between an American Space Shuttle and the station. On June 29,Atlantissuccessfully docked withMir,becoming the first US spacecraft to dock with a Russian spacecraft since theApollo-Soyuz Test Projectin 1975.[25]Atlantisdelivered cosmonautsAnatoly SolovyevandNikolai Budarin,who would form the expedition EO-19 crew, and retrieved astronaut Norman Thagard and cosmonauts Vladimir Dezhurov and Gennady Strekalov of the expedition EO-18 crew.Atlantisalso carried out on-orbit joint US-Russian life sciences investigations aboard aSpacelabmodule and performed a logistical resupply of the station.[20][26][27]

The final Shuttle flight of 1995,STS-74,began with the November 12 launch of Space ShuttleAtlantis,and delivered the Russian-builtDocking ModuletoMir,along with a new pair of solar arrays and other hardware upgrades for the station. The Docking Module was designed to provide more clearance for Shuttles in order to prevent any collisions withMir'ssolar arrays during docking, a problem which had been overcome duringSTS-71by relocating the station'sKristallmodule to a different location on the station. The module, attached toKristall'sdocking port, prevented the need for this procedure on further missions. During the course of the flight, nearly 1,000 pounds (450 kg) of water were transferred toMirand experiment samples including blood, urine and saliva were moved toAtlantisfor return to Earth.[20][28][29][30]

Priroda(1996)[edit]

Continuous US presence aboardMirstarted in 1996 with the March 22 launch ofAtlantison missionSTS-76,when the Second Increment astronautShannon Lucidwas transferred to the station. STS-76 was the third docking mission toMir,which also demonstrated logistics capabilities through deployment of aSpacehabmodule, and placed experiment packages aboardMir'sdocking module, which marked the firstspacewalkwhich occurred around docked vehicles. The spacewalks, carried out fromAtlantis'screw cabin, provided valuable experience for astronauts in order to prepare for later assembly missions to theInternational Space Station.[31]

Lucid became the first American woman to live on station, and, following a six-week extension to her Increment due to issues with ShuttleSolid Rocket Boosters,her 188-day mission set the US single spaceflight record. During Lucid's time aboardMir,thePrirodamodule, with about 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg) of US science hardware, was docked toMir.Lucid made use of bothPrirodaandSpektrto carry out 28 different science experiments and as living quarters.[20][32]

Her stay aboardMirended with the flight ofAtlantisonSTS-79,which launched on September 16. STS-79 was the first Shuttle mission to carry a double Spacehab module. More than 4,000 pounds (1,800 kg) of supplies were transferred toMir,including water generated byAtlantis'sfuel cells,and experiments that included investigations intosuperconductors,cartilagedevelopment, and other biology studies. About 2,000 pounds (910 kg) of experiment samples and equipment were also transferred back fromMirtoAtlantis,making the total transfer the most extensive yet.[33]

This, the fourth docking, also sawJohn Blahatransferring ontoMirto take his place as resident Increment astronaut. His stay on the station improved operations in several areas, including transfer procedures for a docked space shuttle, "hand-over" procedures for long-duration American crew members and "Ham"amateur radiocommunications.

Two spacewalks were carried out during his time aboard. Their aim was to removeelectrical powerconnectors from a 12-year-oldsolar powerarray on the base block and reconnect the cables to the more efficient new solar power arrays. In all, Blaha spent four months with the Mir-22 cosmonaut crew conductingmaterial science,fluid science,andlife scienceresearch, before returning to Earth the next year aboardAtlantisonSTS-81.[20][34]

Fire and collision (1997)[edit]

In 1997STS-81replaced Increment astronaut John Blaha withJerry Linenger,after Blaha's 118-day stay aboardMir.During this fifth shuttle docking, the crew ofAtlantismoved supplies to the station and returned to Earth the first plants to complete a life cycle in space; a crop of wheat planted by Shannon Lucid. During five days of mated operations, the crews transferred nearly 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg) of logistics toMir,and transferred 2,400 pounds (1,100 kg) of materials back toAtlantis(the most materials transferred between the two spacecraft to that date).[35]

The STS-81 crew also tested the Shuttle TreadmillVibration Isolationand Stabilization System (TVIS), designed for use in theZvezdamoduleof the International Space Station. The shuttle's small vernier jet thrusters were fired during the mated operations to gather engineering data for "reboosting" the ISS. After undocking,Atlantisperformed a fly-around ofMir,leaving Linenger aboard the station.[20][35]

During his Increment, Linenger became the first American to conduct a spacewalk from a foreign space station and the first to test the Russian-builtOrlan-Mspacesuit alongside Russian cosmonautVasili Tsibliyev.All three crewmembers of expedition EO-23 performed a "fly-around" in the Soyuz spacecraft, first undocking from one docking port of the station, then manually flying to and redocking the capsule at a different location. This made Linenger the first American to undock from a space station aboard two different spacecraft (Space Shuttle and Soyuz).[24]

Linenger and his Russian crewmates Vasili Tsibliyev andAleksandr Lazutkinfaced several difficulties during the mission. These included the most severe fire aboard an orbiting spacecraft (caused by a backup oxygen-generating device), failures of various on board systems, a near collision with aProgressresupply cargo ship during a long-distance manual docking system test and a total loss of station electrical power. The power failure also caused a loss ofattitude control,which led to an uncontrolled "tumble" through space.[3][9][10][20]

The next NASA astronaut to stay onMirwasMichael Foale.Foale and Russian mission specialistElena KondakovaboardedMirfromAtlantison missionSTS-84.The STS-84 crew transferred 249 items between the two spacecraft, along with water, experiment samples, supplies and hardware. One of the first items transferred toMirwas an Elektron oxygen-generating unit.Atlantiswas stopped three times while backing away during the undocking sequence on May 21. The aim was to collect data from a European sensor device designed for future rendezvous ofESA'sAutomated Transfer Vehicle(ATV) with the International Space Station.[20][36]

Foale's Increment proceeded fairly normally until June 25, when a resupply ship collided with solar arrays on theSpektrmodule during the second test of the Progress manual docking system, TORU. The module's outer shell was hit and holed, which caused the station to lose pressure. This was the first on-orbit depressurization in the history of spaceflight. The crew quickly cut cables leading to the module and closedSpektr'shatch in order to prevent the need to abandon the station in their Soyuz lifeboat. Their efforts stabilized the station's air pressure, whilst the pressure inSpektr,containing many of Foale's experiments and personal effects, dropped to a vacuum. Fortunately, food, water and other vital supplies were stored in other modules, and salvage and replanning effort by Foale and the science community minimized the loss of research data and capability.[9][20]

In an effort to restore some of the power and systems lost following the isolation ofSpektrand to attempt to locate the leak,Mir'snew commanderAnatoly Solovyevandflight engineerPavel Vinogradovcarried out a salvage operation later in the mission. They entered the empty module during a so-called "IVA" spacewalk, inspecting the condition of hardware and running cables through a special hatch fromSpektr'ssystems to the rest of the station. Following these first investigations, Foale and Solovyev conducted a 6-hour EVA on the surface ofSpektrto inspect the damaged module.[20][37]

After these incidents, the US Congress and NASA considered whether to abandon the program out of concern for astronauts' safety but NASA administratorDaniel Goldindecided to continue the program.[10]The next flight toMir,STS-86,brought Increment astronautDavid Wolfto the station.

STS-86 performed the seventh Shuttle–Mirdocking, the last of 1997. DuringAtlantis'sstay crew members Titov and Parazynski conducted the first joint US–Russian extravehicular activity during a Shuttle mission, and the first in which a Russian wore a US spacesuit. During the five-hour spacewalk, the pair affixed a 121-pound (55 kg) Solar Array Cap to theDocking Module,for a future attempt by crew members to seal off the leak inSpektr'shull. The mission returned Foale to Earth, along with samples, hardware, and an old Elektron oxygen generator, and dropped Wolf off on the Station ready for his 128-day Increment. Wolf had originally been scheduled to be the finalMirastronaut, but was chosen to go on the Increment instead of astronautWendy Lawrence.Lawrence was deemed ineligible for flight because of a change in Russian requirements after the Progress supply vehicle collision. The new rules required that allMircrew members should be trained and ready for spacewalks, but a Russian spacesuit could not be prepared for Lawrence in time for launch.[20][38]

Phase One closes down (1998)[edit]

The final year of Phase One began with the flight ofSpace ShuttleEndeavouronSTS-89.The mission delivered cosmonautSalizhan SharipovtoMirand replaced David Wolf withAndy Thomas,following Wolf's 119-day Increment.[20][39]

During his Increment, the last of the program, Thomas worked on 27 science investigations into areas of advanced technology,Earth sciences,human life sciences, microgravity research, and ISS risk mitigation. His stay onMir,considered the smoothest of the entire Phase One program, featured weekly "Letters from the Outpost" from Thomas and passed two milestones for length of spaceflight—815 consecutive days in space by American astronauts since the launch of Shannon Lucid on the STS-76 mission in March 1996, and 907 days ofMiroccupancy by American astronauts dating back to Norman Thagard's trip toMirin March 1995.[20][40]

Thomas returned to Earth on the final Shuttle–Mirmission,STS-91.The mission closed out Phase One, with the EO-25 and STS-91 crews transferring water toMirand exchanging almost 4,700 pounds (2,100 kg) of cargo experiments and supplies between the two spacecraft. Long-term American experiments that had been on boardMirwere also moved intoDiscovery.Hatches were closed for undocking at 9:07 a.m.Eastern Daylight Time(EDT) on June 8 and the spacecraft separated at 12:01 p.m. EDT that day.[20][41][42]

Phases Two and Three: ISS (1998–present)[edit]

With the landing ofDiscoveryon June 12, 1998, the Phase One program concluded. Techniques and equipment developed during the program assisted the development of Phase Two: initial assembly of the International Space Station (ISS). The arrival of theDestinyLaboratory Modulein 2001 marked the end of Phase Two and the start of Phase Three, the final outfitting of the station, completed in 2012.[43]

In 2015, a reconfiguration of the American segment was completed to allow its docking ports to accommodate NASA-sponsored commercial crew vehicles, that were expected to start visiting the ISS in 2018.[44]

As of June 2015[update],the ISS has a pressurized volume of 915 cubic metres (32,300 cu ft), and its pressurized modules total 51 metres (167 ft) in length, plus a large truss structure that spans 109 metres (358 ft), making it the largest spacecraft ever assembled.[45]The completed station consists of five laboratories and is able to support six crew members. With over 332 cubic metres (11,700 cu ft) of habitable volume and a mass of 400,000 kilograms (880,000 lb) the completed station is almost twice the size of the combined Shuttle–Mirspacecraft.[45]

Phases Two and Three are intended to continue both international cooperation in space and zero-gravity scientific research, particularly regarding long-duration spaceflight. By spring 2015,Roscosmos,NASA, and theCanadian Space Agency(CSA) have agreed to extend the ISS's mission from 2020 to 2024.[46]

In 2018 that was then extended out to 2030.[47]The results of this research will provide considerable information for long-duration expeditions to theMoonand flights toMars.[48]

Following the intentional deorbiting ofMiron 23 March 2001, the ISS became the only space station in orbit around Earth.[49]It retained that distinction until the launch of ChineseTiangong-1space laboratory on 29 September 2011.[50]

Mir'slegacy lives on in the station, bringing together five space agencies in the cause of exploration and allowing those space agencies to prepare for their next leap into space, to the Moon, Mars and beyond.[51]

Complete list of Shuttle–Mirmissions[edit]

| Mission | Launch Date | Shuttle | Patch | Crew | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STS-60 | 3 February 1994 | Discovery |  |

First Russian cosmonaut on US spacecraft | Deployed theWake Shield Facility| Carried theSpaceHabsingle module | |

| STS-63 | 3 February 1995 | Discovery |  |

First Shuttle rendezvous withMir | |

| Soyuz TM-21 | 14 March 1995 |  |

First American astronaut on Russian spacecraft | DeliveredMir-EO-18crew | Delivered Norman Thagard for long-duration stay | ||

| STS-71 | 27 June 1995 | Atlantis | First Shuttle–Mirdocking | DeliveredMir EO-19crew | Returned Mir EO-18 crew | ||

| STS-74 | 12 November 1995 | Atlantis |  |

Delivered theMirDocking Module| Hadfield became first and only Canadian to visitMir | |

| STS-76 | 22 March 1996 | Atlantis |  |

Delivered Shannon Lucid for long-duration stay | Carried the SpaceHab single module | |

| STS-79 | 16 September 1996 | Atlantis |  |

First flight of the SpaceHab double module | Delivered John Blaha for long-duration stay | Returned Shannon Lucid from long-duration stay | |

| STS-81 | 12 January 1997 | Atlantis | Delivered Jerry Linenger for long-duration stay | Returned John Blaha from long-duration stay | ||

| STS-84 | 15 May 1997 | Atlantis | Delivered Michael Foale for long-duration stay | Returned Jerry Linenger from long-duration stay | ||

| STS-86 | 26 September 1997 | Atlantis |  |

Vladimir Titov became first Russian cosmomaut to use anEMU| Delivered David Wolf for long-duration stay | Returned Michael Foale from long-duration stay | |

| STS-89 | 31 January 1998 | Endeavour |  |

Delivered Andrew Thomas for long-duration stay | Returned David Wolf from long-duration stay | |

| STS-91 | 2 June 1998 | Discovery |  |

Final Shuttle Mir mission | Returned Andrew Thomas from long-duration stay |

Controversy[edit]

Safety and scientific return[edit]

Criticism of the program was primarily concerned with the safety of the agingMir,particularly following the fire aboard the station and collision with the Progress supply vessel in 1997.[10]

The fire, caused by the malfunction of a backupsolid-fuel oxygen generator(SFOG), burned for, according to various sources, between 90 seconds and 14 minutes, and produced large amounts of toxic smoke that filled the station for around 45 minutes. This forced the crew to don respirators, but some of the respirator masks initially worn were broken.Fire extinguishersmounted on the walls of the modules were immovable. The fire occurred during a crew rotation, and as such there were six men aboard the station rather than the usual three. Access to one of the docked Soyuz lifeboats was blocked, which would have prevented escape by half of the crew. A similar incident had occurred on an earlierMirexpedition, although in that case the SFOG burned for only a few seconds.[9][10]

The near-miss and collision incidents presented further safety issues. Both were caused by failure of the same piece of equipment, the TORU manual docking system, which was undergoing tests at the time. The tests were called in order to gauge the performance of long-distance docking in order to enable the cash-strapped Russians to remove the expensiveKursautomatic docking system from the Progress ships.

In the wake of the collision NASA and the Russian Space Agency instigated numerous safety councils who were to determine the cause of the accident. As their investigations progressed, the two space agencies results began moving in different directions. NASA's results blamed the TORU docking system, as it required the astronaut or cosmonaut in charge to dock the Progress without the aide of any sort of telemetry or guidance. However, the Russian Space Agency's results blamed the accident on crew error, accusing their own cosmonaut of miscalculating the distance between the Progress and the space station.[52]The Russian Space Agency's results were heavily criticized, even by their own cosmonaut Tsibliyev, on whom they were placing the blame. During his first press conference following his return to Earth, the cosmonaut expressed his anger and disapproval by declaring, "It has been a long tradition here in Russia to look for scapegoats."[53]

The accidents also added to the increasingly vocal criticism of the aging station's reliability. AstronautBlaine Hammondclaimed that his safety concerns aboutMirwere ignored by NASA officials, and that records of safety meetings "disappeared from a locked vault".[54]Mirwas originally designed to fly for five years but eventually flew for three times that length of time. During Phase One and afterward, the station was showing her age—constant computer crashes, loss of power, uncontrolled tumbles through space and leaking pipes were an ever-present concern for crews. Various breakdowns ofMir'sElektron oxygen-generating system were also a concern. These breakdowns led crews to become increasingly reliant on the SFOG systems that caused the fire in 1997. SFOG systems continue to be a problem aboard the ISS.[9]

Another issue of controversy was the scale of its actual scientific return, particularly following the loss of theSpektrscience module. Astronauts, managers and various members of the press all complained that the benefits of the program were outweighed by the risks associated with it, especially considering the fact that most of the US science experiments had been contained within the holed module. As such, a large amount of American research was inaccessible, reducing the science that could be performed.[55]The safety issues caused NASA to reconsider the future of the program at various times. The agency eventually decided to continue and came under fire from various areas of the press regarding that decision.[56]

Attitudes[edit]

Attitudes of the Russian space program and NASA towards Phase One were also of concern to the astronauts involved. Because of Russia's financial issues, many workers at theTsUPfelt that the mission hardware and continuation ofMirwas more important than the lives of the cosmonauts aboard the station. As such the program was run very differently compared to American programs: cosmonauts had their days being planned for them to the minute, actions (such as docking) which would be performed manually by shuttle pilots were all carried out automatically, and cosmonauts had their pay docked if they made any errors during their flights. Americans learned aboardSkylaband earlier space missions that this level of control was not productive and had since made mission plans more flexible. The Russians, however, would not budge, and many felt that significant work time was lost because of this.[9][57]

Following the two accidents in 1997, astronautJerry Linengerfelt that the Russian authorities attempted a cover-up to downplay the significance of the incidents, fearing that the Americans would back out of the partnership. A large part of this "cover-up" was the seeming impression that the American astronauts were not in fact "partners" aboard the station, but were instead "guests". NASA staff did not find out for several hours about the fire and collision and found themselves kept out of decision-making processes. NASA became more involved when Russian mission controllers intended to place blame for the accident entirely onVasily Tsibliyev.It was only after the application of significant pressure from NASA that this stance was changed.[9][10]

At various times during the program, NASA managers and personnel found themselves limited in terms of resources and manpower, particularly as Phase Two geared up, and had a hard time getting anywhere with NASA administration. One particular area of contention was with crew assignments to missions. Many astronauts allege that the method of selection prevented the most skilled people from performing roles they were best-suited for.[9][10][58]

Finances[edit]

Since thebreakup of the Soviet Uniona few years earlier, theRussian economyhad been slowly collapsing and the budget for space exploration was reduced by around 80%. Before and after Phase One, a great deal of Russia's space finances came from flights of astronauts fromEuropeand other countries, with one JapaneseTV stationpaying $9.5 million to have one of their reporters,Toyohiro Akiyama,flown aboardMir.[9]By the start of Phase One, cosmonauts regularly found their missions extended to save money on launchers, the six-yearly flights of theProgresshad been reduced to three, and there was a distinct possibility ofMirbeing sold for around $500 million.[9]

Critics argued that the $325 million contract NASA had with Russia was the only thing keeping the Russian space program alive, and only the Space Shuttle was keepingMiraloft. NASA also had to pay hefty fees fortraining manualsand equipment used by astronauts training atStar City.[10]Problems came to a head whenABC'sNightlinerevealed that there was a distinct possibility of embezzlement of American finances by the Russian authorities in order to build a suite of new cosmonaut houses inMoscow,or else that the building projects were being funded by theRussian Mafia.NASA administrator Goldin was invited ontoNightlineto defend the homes but he refused to comment. NASA's office for external affairs was quoted as saying, "What Russia does with its own money is their business."[9][59]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

![]() This article incorporatespublic domain materialfrom websites or documents of theNational Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporatespublic domain materialfrom websites or documents of theNational Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^NASA.gov.Retrieved 27 November 2020

- ^s:Mir Hardware Heritage/Part 2 - Almaz, Salyut, and Mir#2.1.6 Shuttle-Salyut (1973-1978; 1980s)

- ^abcdefghiDavid Harland (November 30, 2004).The Story of Space Station Mir.New York: Springer-Verlag New York Inc.ISBN978-0-387-23011-5.

- ^Al-Khatib, Talal (22 February 2016)."30 Years Later: The Legacy of the Mir Space Station".Space.Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2023.Retrieved23 May2023.

- ^Donna Heivilin (June 21, 1994)."Space Station: Impact of the Expanded Russian Role on Funding and Research"(PDF).Government Accountability Office.Archived(PDF)from the original on July 21, 2011.RetrievedNovember 3,2006.

- ^Kim Dismukes (April 4, 2004)."Shuttle–Mir History/Background/How" Phase 1 "Started".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon November 16, 2001.RetrievedApril 12,2007.

- ^Kim Dismukes (April 4, 2004)."Shuttle–Mir History/Welcome/Goals".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon November 13, 2001.RetrievedApril 12,2007.

- ^George C. Nield & Pavel Mikhailovich Vorobiev (January 1999).Phase One Program Joint Report(PDF)(Report). NASA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2004-11-17.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^abcdefghijklmBryan Burrough (January 7, 1998).Dragonfly: NASA and the Crisis Aboard Mir.London, UK: Fourth Estate Ltd.ISBN978-1-84115-087-1.ASIN1841150878.

- ^abcdefghijLinenger, Jerry(January 1, 2001).Off the Planet: Surviving Five Perilous Months Aboard the Space Station Mir.New York, USA: McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0-07-137230-5.ASIN007137230X.

- ^David S. F. Portree (March 1995)."Mir Hardware Heritage"(PDF).NASA Sti/Recon Technical Report N.95:23249. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 September 2009.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Launius, Roger D."Space Task Group Report, 1969".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-12-24.Retrieved2019-08-15.

- ^Malik, Tarik (July 21, 2011)."NASA's Space Shuttle By the Numbers: 30 Years of a Spaceflight Icon".Space.Archivedfrom the original on May 23, 2019.RetrievedJune 18,2014.

- ^Jim Wilson (March 5, 2006)."Shuttle Basics".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on October 3, 2009.RetrievedSeptember 21,2009.

- ^David M. Harland (July 5, 2004).The Story of the Space Shuttle.Springer-Praxis.ISBN978-1-85233-793-3.

- ^abSue McDonald (December 1998).Mir Mission Chronicle(PDF)(Report). NASA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on May 31, 2010.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Kim Dismukes (April 4, 2004)."Shuttle–Mir History/Spacecraft/Space Shuttle Orbiter".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon November 10, 2001.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Justin Ray (April 14, 2000)."Columbia Weight Loss Plan".Spaceflight Now.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2011.RetrievedOctober 29,2009.

- ^William Harwood (February 4, 1994). "Space Shuttle Launch Begins Era of US-Russian Cooperation".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a3.

- ^abcdefghijklmno "Shuttle–Mir History/Shuttle Flights and Mir Increments".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon November 11, 2001.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-60 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2016.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-63 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 20, 2009.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Kathy Sawyer (January 29, 1995). "US & Russia Find Common Ground in Space – Nations Overcome Hurdles in Ambitious Partnership".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a1.

- ^abList of Mir expeditions

- ^Scott, David;Leonov, Alexei(April 30, 2005).Two Sides of the Moon.Pocket Books.ISBN978-0-7434-5067-6.ASIN0743450671.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-71 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 29, 2015.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Nick Nuttall (June 29, 1995). "Shuttle homes in for Mir docking".The Times.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank.

- ^ "CSA – STS-74 – Daily Reports".Canadian Space Agency. October 30, 1999. Archived fromthe originalon July 16, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 17,2009.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-74 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on December 20, 2016.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^William Harwood (November 15, 1995). "Space Shuttle docks with Mir – Atlantis uses manoeuvres similar to those needed for construction".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a3.

- ^William Harwood (March 28, 1996). "Shuttle becomes hard-hat area; spacewalking astronauts practice tasks necessary to build station".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a3.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-76 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on August 6, 2013.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^William Harwood (September 20, 1996). "Lucid transfers from Mir to Space Shuttle".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a3.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-79 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2007.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^abJim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-81 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on May 20, 2007.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-84 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on February 10, 2007.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^ David Hoffman (August 22, 1997). "Crucial Mir spacewalk carries high hopes – continued Western support could hinge on mission's success".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a1.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-86 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2016.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-89 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^Thomas, Andrew(September 2001)."Letters from the Outpost".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on October 8, 2006.RetrievedApril 15,2007.

- ^Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001)."STS-91 Mission Summary".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedMarch 30,2007.

- ^William Harwood (June 13, 1998). "Final American returns from Mir".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. a12.

- ^Esquivel, Gerald (23 March 2003)."ISS Phases I, II and III".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-12-14.Retrieved2007-06-27.

- ^Harding, Pete (26 May 2015)."ISS relocates PMM in reconfiguration for future crew vehicles".NASA Spaceflight.Archivedfrom the original on 1 June 2015.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^abGarcia, Mark (30 April 2015)."ISS Facts and Figures".International Space Station.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2015.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Clark, Stephen (24 February 2015)."Russian Space Agency Endorses ISS Until 2024".Spaceflight Now.Archivedfrom the original on 14 June 2015.Retrieved2015-06-14.

- ^"Senate passes commercial space bill".SpaceNews.2018-12-21.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-09-27.Retrieved2019-03-26.

- ^Garcia, Mark (30 April 2015)."International Cooperation".International Space Station.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2015.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Boyle, Alan (23 March 2001)."Russia bids farewell to Mir".NBC News.New York.Archivedfrom the original on 15 June 2015.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Malik, Tariq (29 September 2011)."China's Tiangong 1 Space Lab: Questions & Answers".Space.Archivedfrom the original on 26 September 2015.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Cabbage, Michael (31 July 2005)."NASA outlines plans for Moon and Mars".Orlando Sentinel.Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2007.Retrieved2009-09-17.

- ^Burrough, Bryan (1999).Dragonfly.Fourth Estate.

- ^Specter, Michael (17 August 1997). "Refusing To Play Role Of Mir's Scapegoat, Crew Fights Back".New York Times.

- ^Alan Levin (February 6, 2003)."Some question NASA experts' objectivity".USA Today.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-06-04.Retrieved2017-08-22.

- ^James Oberg (September 28, 1997). "NASA's 'Can-Do' style is clouding its vision of Mir".Washington Post.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. p. C1.

- ^Mark Prigg (April 20, 1997). "Row between Nasa and the Russian Space Agency – Innovation".The Sunday Times.Retrieved March 9, 2007 from NewsBank. Sport 20.

- ^Leland F. Belew (1977)."9 The Third Manned Period".SP-400 Skylab, Our First Space Station.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on March 16, 2007.RetrievedApril 6,2007.

- ^Ben Evans (2007).Space Shuttle Challenger: Ten Journeys into the Unknown.Warwickshire, United Kingdom: Springer-Praxis.ISBN978-0-387-46355-1.ASIN0387463550.

- ^"SpaceViews Update 97 May 15: Policy".Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. May 15, 1997. Archived fromthe originalon March 12, 2005.RetrievedApril 5,2007.

External links[edit]

- History of Shuttle–Mir(NASA)

- Diary of Linenger Increment(NASA)

- Shuttle–Mir'sLessons for the International Space Station James Oberg, Contributing Editor, SPECTRUM magazine June 1998, pp. 28–37