Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar | |

|---|---|

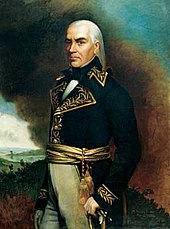

Posthumous portrait, 1922 | |

| 1stPresident of Colombia | |

| In office 16 February 1819 – 27 April 1830 | |

| Preceded by | Estanislao Vergara y Sanz de Santamaría |

| Succeeded by | Domingo Caycedo |

| 4thPresident of Peru[a] | |

| In office 10 February 1824 – 27 January 1827 | |

| Preceded by | José Bernardo de Tagle |

| Succeeded by | José de La Mar |

| 1stPresident of Bolivia[b] | |

| In office 6 August 1825 – 29 December 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Antonio José de Sucre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 July 1783 Caracas,Captaincy General of Venezuela,Spanish Empire |

| Died | 17 December 1830(aged 47) Santa Marta,Gran Colombia(now Colombia) |

| Resting place | National Pantheon of Venezuela |

| Nationality |

|

| Spouse | |

| Domestic partner | Manuela Sáenz |

| Signature |  |

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco[c](24July 1783 – 17December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries ofColombia,Venezuela,Ecuador,Peru,Panama,andBoliviato independence from theSpanish Empire.He is known colloquially asEl Libertador,or theLiberator of America.

Simón Bolívar was born inCaracasin theCaptaincy General of Venezuelainto a wealthy family of American-born Spaniards (criollo) but lost both parents as a child. Bolívar was educated abroad and lived in Spain, as was common for men of upper-class families in his day. While living inMadridfrom 1800 to 1802, he was introduced toEnlightenment philosophyand marriedMaría Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaysa,who died in Venezuela fromyellow feverin 1803. From 1803 to 1805, Bolívar embarked on aGrand Tourthat ended inRome,where he swore to end theSpanish rule in the Americas.In 1807, Bolívar returned to Venezuela and promoted Venezuelan independence to other wealthy creoles. When the Spanish authority in the Americas weakened due toNapoleon's Peninsular War,Bolívar became a zealous combatant and politician in theSpanish-American wars of independence.

Bolívar beganhis military careerin 1810 as a militia officer in theVenezuelan War of Independence,fightingRoyalistforces for thefirstandsecondVenezuelan republics and theUnited Provinces of New Granada.After Spanish forcessubdued New Granadain 1815, Bolívar was forced into exile onJamaica.InHaiti,Bolívar met and befriended Haitian revolutionary leaderAlexandre Pétion.After promising to abolish slavery in Spanish America, Bolívar received military support from Pétion and returned to Venezuela. He established athird republicin 1817 and then crossed the Andes toliberate New Granadain 1819. Bolívar and his allies defeated the Spanish in New Granada in 1819, Venezuela and Panama in 1821, Ecuador in 1822, Peru in 1824, and Bolivia in 1825. Venezuela, New Granada, Ecuador, and Panama were merged into theRepublic of Colombia(Gran Colombia), with Bolívar as president there and in Peru and Bolivia.

In his final years, Bolívar became increasingly disillusioned with the South American republics, and distanced from them because of his centralist ideology. He was successively removed from his offices until he resigned the presidency of Colombia and died oftuberculosisin 1830. His legacy is diverse and far-reaching within Latin America and beyond. He is regarded as a hero andnational and cultural iconthroughout Latin America; the nations of Bolivia and Venezuela (as the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela) are named after him, and he has been memorialized all over the world in the form of public art or street names and in popular culture.

Early life and family[edit]

Simón Bolívar was born on 24 July 1783 inCaracas,capital of theCaptaincy General of Venezuela,the fourth and youngest child ofJuan Vicente Bolívar y PonteandMaría de la Concepción Palacios y Blanco.[5]He wasbaptizedas Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios on 30 July.[6]The first of Bolívar's family to have emigrated to the Americas was a similarly named minor Spanish governmental official named Simón de Bolívar, who had been a notary in the SpanishBasque region,and who had later arrived in Venezuela in the 1580s.[7]The earlier Simón de Bolívar's descendants had served in the colonial bureaucracy and had married into various wealthy Caracas families over the years.[8]By the time Simón Bolívar was born, theBolívar familywas one of the wealthiest and most prestigiouscriollo(creole) families in the Spanish Americas.[9]

Simón Bolívar's childhood was described by British historianJohn Lynchas "at once privileged and deprived."[10]Juan Vicente died of tuberculosis on 19 January 1786,[11]leaving María de la Concepción Palacios and her father,Feliciano Palacios y Sojo,[12]aslegal guardiansover the Bolívar children's inheritances.[13]Those children –María Antonia(born 1777),Juana(born 1779),Juan Vicente(born 1781), and Simón[14]– were raised separately from each other and their mother, and, following colonial custom, by Africanhouse slaves;[15]Simón was raised by a slave namedHipólitawhom he viewed as both a motherly and fatherly figure.[16]On 6 July 1792,[17]María de la Concepción also died of tuberculosis.[18]Believing that his family would inherit the Bolívars' wealth,[19]Feliciano Palacios arranged marriages for María Antonia and Juana and,[20]before dying on 5 December 1793,[21]assigned custody of Juan Vicente and Simón to his sons, Juan Félix Palacios andCarlos Palacios y Blanco,respectively.[22]Bolívar came to loathe Carlos Palacios,[23]who had no interest in the boy other than his inheritance.[24]

Education and first journey to Europe: 1793–1802[edit]

As a child, Bolívar was notoriously unruly[25]and neglected his studies.[19]Before his mother died, he spent two years under the tutelage of the Venezuelan lawyerMiguel José Sanzat the direction of theReal Audiencia of Caracas,theSpanish court of appealsin Caracas.[26]In 1793, Carlos enrolled Bolívar at arudimentary primary schoolrun by Venezuelan educatorSimón Rodríguez.[27]In June 1795, Bolívar fled his uncle's custody for the house of his sister María Antonia and her husband.[28]The couple sought formal recognition of his change of residence,[29]but the Real Audiencia decided the matter in favor of Palacios, who sent Simón to live with Rodríguez.[30]

After two months there, the Real Audiencia directed that he be returned to the Palacios family home.[31]Bolívar promised the Real Audiencia that he would focus on his education and was subsequently taught full-time by Rodríguez and the Venezuelan intellectualsAndrés BelloandFrancisco de Andújar.[32]In 1797, Rodríguez's connection to the pro-independenceGual and España conspiracyforced him to go into exile,[33]and Bolívar was enrolled in an honorary militia force. When he was commissioned as an officer after a year,[34]his uncles Carlos andEsteban Palacios y Blancodecided to send Bolívar to join the latter inMadrid.[35]There, Esteban was friends with QueenMaria Luisa'sfavorite,Manuel Mallo.[36]

On 19 January 1799, Bolívar boarded the Spanish warshipSan Ildefonsoat the port ofLa Guaira,[37]bound forCádiz.[38]He arrived inSantoña,on the northern coast of Spain, in May 1799.[39]A little over a week later,[40]he arrived in Madrid and joined Esteban,[41]who found Bolívar to be "very ignorant."[42]Esteban asked Gerónimo Enrique de Uztáriz y Tovar, a Caracas native and government official, to educate Bolívar.[43][44]Bolívar moved into Uztáriz's residence in February 1800 and was educated in theClassics,literature, and social studies.[45][46]

At the same time, Mallo fell out of the Queen's favor andManuel Godoy,her previous favorite, returned to power.[47]As members of Mallo's faction at court, Esteban was arrested on pretense,[48]and Bolívar was banished from court following a public incident at thePuerta de Toledoover the wearing of diamonds without royal permission.[49]Bolívar also at this time metMaría Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaysa,the daughter of another wealthy Caracas creole.[50]They wereengagedin August 1800,[51]but were separated when the del Toros left Madrid for asummer homeinBilbao.[52]After Uztáriz left Madrid for a government assignment inTeruelin 1801,[51][53]Bolívar himself left for Bilbao and remained there when the del Toros returned to the capital in August 1801.[54]Early in 1802, Bolívar traveled toPariswhile he awaited permission to return to Madrid, which was granted in April.[55]

Return to Venezuela and second journey to Europe: 1802–1805[edit]

Bolívar and del Toro, aged 18 and 21 respectively, were married in Madrid on 26 May 1802.[56]The couple boarded theSan IldefonsoinLa Coruña[57]on 15 June and sailed for La Guaira, where they arrived on 12 July.[51]They settled in Caracas, where del Toro fell ill and died ofyellow feveron 22 January 1803.[58]Bolívar was devastated by del Toro's death and later toldLouis Peru de Lacroix,one of his generals and biographers, that he swore to never remarry.[59]By July 1803,[60]Bolívar had decided to leave Venezuela for Europe. He entrusted his estates to an agent and his brother and in October boarded a ship bound for Cádiz.[61]

Bolívar arrived in Spain in December 1803, then traveled to Madrid to console his father-in-law.[62]In March 1804, the municipal authorities of Madrid ordered all non-residents in the city to leave to alleviate a bread shortage brought about by Spain's resumed hostilities with Britain.[63][64]Over April, Bolívar andFernando Rodríguez del Toro,a childhood friend and relative of his wife, made their way to Paris and arrived in time forNapoleonto be proclaimedEmperor of the Frenchon 18 May 1804.[65]They rented an apartment on theRue Vivienneand met with other South Americans such asCarlos de Montúfar,Vicente Rocafuerte,and Simón Rodríguez, who joined Bolívar and del Toro in their apartment. While in Paris, Bolívar began adalliancewith the Countess Dervieu du Villars,[66]at whosesalonhe likely met the naturalistsAlexander von HumboldtandAimé Bonpland,who had traveled through much ofSpanish Americafrom 1799 to 1804. Bolívar allegedly discussed Spanish American independence with them.[67]

I swear before you... that I will not rest body or soul until I have broken the chains binding us to the will of Spanish might!

Simón Bolívar, 15 August 1805[68]

In April 1805, Bolívar left Paris with Rodríguez and del Toro on aGrand TourtoItaly.[69]Beginning inLyon,they traveled through theSavoy Alpsand then toMilan.[70]The trio arrived on 26 May 1805 and witnessed Napoleon's coronation asKing of Italy.[71]From Milan, they traveled down thePo ValleytoVenice,then toFlorence,and then finallyRome,[72]where Bolívar met, among others,Pope Pius VII,French writerGermaine de Staël,and Humboldt again.[73]Rome's sites and history excited Bolívar. On 18 August 1805, when he, del Toro, and Rodríguez traveled to theMons Sacer,wherethe plebs had seceded from Romein the 4th century BC, Bolívar swore to end Spanish rule in the Americas.[74]

Political and military career[edit]

By April 1806, Bolívar had returned to Paris and desired passage to Venezuela,[75]where Venezuelan revolutionaryFrancisco de Mirandahad just attempted an invasion with American volunteers.[76]Britishcontrol of the seasresulting from the 1805Battle of Trafalgar,however, obliged Bolívar to board an American ship inHamburgin October 1806. Bolívar arrived inCharleston, South Carolina,in January 1807,[77]and from there traveled toWashington, D.C.,Philadelphia,New York City,andBoston.[78]After six months in theUnited States,[79]Bolívar returned to Philadelphia and sailed for Venezuela, where he arrived in June 1807. He began to meet with other creole elites to discuss independence from Spain.[80]Finding himself to be far more radical than the rest of Caracas high society,[81]however, Bolívar occupied himself with a property dispute with a neighbor,Antonio Nicolás Briceño.[82]

In 1807–08, Napoleoninvaded the Iberian peninsulaandreplaced the rulers of Spainwith his brother,Joseph.[83]This news arrived in Venezuela in July 1808.[84]Napoleonic rule was rejected and Venezuelan creoles, though still loyal toFerdinand VII of Spain,sought to form their own local government in place of the existing Spanish government.[85]On 24 November 1808, a group of creoles presented a petition demanding an independent government toJuan de Casas,the Captain-General of Venezuela, and were arrested.[86]Bolívar, though he did not sign the petition and thus was not arrested, was warned to cease hosting or attending seditious meetings.[87]In May 1809, Casas was replaced byVicente Emparánand his staff, which included Fernando Rodríguez del Toro. The creoles also resisted Emparán's government, despite his friendlier disposition towards them.[88]

By February 1810, French victories in Spain prompted the dissolution ofthe anti-French Spanish governmentin favor of a five-manregency councilfor Ferdinand VII.[89]This news, and two delegates that included Carlos de Montúfar, arrived in Venezuela on 17 April 1810.[90]Two days later, the creoles succeeded in deposing and then expelling Emparán,[91]and created theSupreme Junta of Caracas,independent from the Spanish regency but not Ferdinand VII.[92][93]Absent from Caracas for thecoup,[94]Bolívar and his brother returned to the city and offered their services to the Supreme Junta as diplomats.[95]In May 1810, Juan Vicente was sent to the United States to buy weapons,[96]while Simón secured a place in a diplomatic mission toGreat Britainwith the lawyerLuis López Méndezand Andrés Bello by paying for the mission. The trio boarded a British warship in June 1810 and arrived atPortsmouthon 10 July 1810.[97]

The three delegates first met Miranda at his London residence, despite instructions from the Supreme Junta to avoid him, and thereafter received the benefit of his connections and consultation.[98]On 16 July 1810, the Venezuelan delegation met theBritish foreign secretary,Richard Wellesley,athis residence.Led by Bolívar, the Venezuelans argued in favor of Venezuelan independence, which Wellesley stated that it was intolerable forAnglo-Spanish relations.[99]Subsequent meetings produced no recognition or concrete support from Britain.[100]Finding that he had many shared beliefs with Miranda, however, Bolívar convinced him to come back to Venezuela.[101]On 22 September 1810,[102]Bolívar left for Venezuela while López and Bello remained in London as diplomats,[103]and arrived in La Guaira on 5 December.[104]Although the British government wanted Miranda to remain in Britain, they could not prevent his departure,[105]and he arrived in Venezuela later in December.[106][d]

Venezuela: 1811–1812[edit]

While Bolívar was in England, the Supreme Junta passedliberaleconomic reforms[112]and began to hold elections for representatives to a congress to be held in Caracas.[113]It had also alienated Caracas from the Venezuelan provinces ofCoro,Maracaibo,andGuayana,which professed loyalty to the regency council,[114]and began hostilities with them.[115][116]Co-founding thePatriotic Society,a political organization advocating for independence from Spain, Bolívar and Miranda campaigned for and secured the latter's election to the congress.[117]The congress first met on 2 March 1811 and declared its allegiance to Ferdinand VII.[118]After it was discovered that one of the men leading the congress was a Spanish agent who had escaped with military documents, however,[119]discourse – which Bolívar was prominent in – changed decidedly in favor of independence over 3 and 4 July.[120]Finally, on 5 July, the congressdeclared Venezuela's independence.[121]

The declaration of independence created the firstRepublic of Venezuela.It had a weak base of support and enemies in conservative whites, disenfranchised people of color, and the already hostile Venezuelan provinces, which received troops and supplies from theCaptaincy-Generals of Puerto RicoandCuba.[122]On 13 July 1811, the republic raised militias to fight the pro-SpanishRoyalists.[123]The congress appointedFrancisco Rodríguez del Toro,theMarquis of Toro,to command these forces,[124]which opened a breach between Bolívar and Miranda. Bolívar and del Toro were close friends, while del Toro and Miranda and their families were enemies.[125]After he failed to suppress a Royalist uprising in the city ofValencialater in July,[126]the congress replaced del Toro with Miranda, and herecaptured Valenciaon 13 August.[127]As a condition of assuming command of the Republican forces, Miranda had Bolívar stripped of his command of a militia unit.[128]Bolívar nonetheless fought in the Valencia campaign as part of del Toro's militia[129]and was selected by Miranda to bring news of its recapture to Caracas,[130]where he argued for more punitive and forceful campaigning against the Royalists.[131]

I left my house for the Cathedral... and the earth began to shake with a huge roar.... I saw the church of San Jacinto collapse on its own foundations.... I climbed over the ruins and entered, and I immediately saw about forty persons dead or dying under the rubble. I climbed out again and I shall never forget that moment. On the top of the ruins I found Don Simón Bolívar... He saw me and [said], "We will fight nature itself if it opposes us, and force it to obey."

Royalist historianJosé Domingo Díaz,quoted byJohn Lynch[132]

Beginning in November 1811, Royalist forces began pushing back the Republicans from the north and east.[133]On 26 March 1812, apowerful earthquakedevastated Republican Venezuela; Caracas itself was almost totally destroyed.[134]Bolívar, who was still near Caracas,[135]rushed into the city to participate in the rescue of survivors and exhumation of the dead.[136]The earthquake destroyed public support for the republic, as it was believed to have beendivine retributionfor declaring independence from Spain.[137]By April, a Royalist army under the Spanish naval officerJuan Domingo de Monteverdeoverran western Venezuela. Miranda,[138]retreating east with a disintegrating army,[139]ordered Bolívar to assume command of the coastal city ofPuerto Cabelloandits fortress,[140]which contained Royalist prisoners and most of the republic's remaining arms and ammunition.[141]

Bolívar arrived at Puerto Cabello on 4 May 1812.[142]On 30 June, an officer of the fort's garrison loyal to the Royalists released its prisoners, armed them, and turned its cannons on Puerto Cabello.[139][143]Weakened by shelling, defections, and lack of supplies, Bolívar and his remaining troops fled for La Guaira on 6 July.[144]Believing the republic to be doomed,[139]Miranda decided to capitulate,[145]shocking Bolívar and other Republican officers.[146]After formally surrendering his command to Monteverde on 25 July,[147]Miranda made his way to La Guaira, where a group of officers including Bolívar arrested Miranda on 30 July on charges of treason against the republic.[148]La Guaira declared for the Royalists the next day and closed its port on Monteverde's orders.[149]Miranda was taken into Spanish custody and moved to a prison in Cádiz, where he died on 16 July 1816.[150]

New Granada and Venezuela: 1812–1815[edit]

Bolívar escaped La Guaira early on 31 July 1812 and rode to Caracas,[151]where he hid from arrest in the home ofEsteban Fernández de León,theMarquis de Casa León.Bolívar and Casa León convinced Francisco Iturbe, a friend of the Bolívar family and of Monteverde, to intercede on Bolívar's behalf and secure escape from Venezuela for him. Iturbe persuaded Monteverde to issue Bolívar a passport for his role in Miranda's arrest,[152]and on 27 August he sailed for the island ofCuraçao.He and his uncles'FranciscoandJosé Félix Ribasarrived on 1 September. Late in October, the exiles arranged for passage west to the city ofCartagenato offer their services as military leaders to theUnited Provinces of New Granadaagainst the Royalists.[153]They arrived in November and were welcomed byManuel Rodríguez Torices,president of theFree State of Cartagena,[154]who instructed his commanding general,Pierre Labatut,to give Bolívar a military command. Labatut, a former partisan of Miranda, begrudgingly obliged and on 1 December 1812 placed Bolívar in command of the 70-man garrison of a town on the lowerMagdalena River.[155]

While en route to his posting, Bolívar issued theCartagena Manifesto,outlining what he believed to be the causes of the Venezuelan republic's defeat and his political program. In particular, Bolívar called for the disparate New Granadan republics to help him invade Venezuela to prevent a Royalist invasion of New Granada.[156]Bolívar arrived on the Magdalena River on 21 December and,[157]in spite of orders from Labatut to not act without his direction,[158]launchedan offensivethat secured control of the Magdalena River from Royalist forces by 8 January 1813.[159]In February, he joined forces with Republican colonelManuel del Castillo y Rada,who requested Bolívar's assistance with stopping a Royalist advance into New Granada from Venezuela, andcapturedthe city ofCúcutafrom the Royalists.[160]

In early March 1813, Bolívar set up his headquarters in Cúcuta and sent José Félix Ribas to request permission to invade Venezuela.[161]Though rewarded with honorary citizenship in New Granada and a promotion to the rank ofbrigadier general,[162]that permission did not come until 7 May because of del Castillo's opposition to the invasion. When a limited invasion was permitted, Castillo resigned his command and was succeeded byFrancisco de Paula Santander.[163]On 14 May, Bolívar launched theAdmirable Campaign,[164]in which he issued theDecree of War to the Death,ordering the death of all Spaniards in South America not actively aiding his forces.[165]Within six months, Bolívar pushed all the way to Caracas,[166]which he entered on 6 August,[167][168]and then drove Monteverde out of Venezuela in October.[169][170]Bolívar returned to Caracas on 14 October and was named "The Liberator" (El Libertador) by its town council,[171]a title first given to him by the citizens of the Venezuelan town ofMéridaon 23 May.[172]

On 2 January 1814, Bolívar was made thedictatorof aSecond Republic of Venezuela,[173]which retained the weaknesses of the first republic.[174]Though all of Venezuela butMaracaibo,Coro,and Guayana was controlled by Republicans,[175][176]Bolívar only governed western Venezuela. The east was controlled bySantiago Mariño,a Venezuelan Republican who had fought Monteverde in the east throughout 1813[177][178]and was unwilling to subordinate himself to Bolívar.[179]Venezuela was economically devastated and could not support the republic's armies,[180]and people of color remained disenfranchised and thus unsupportive of the republic.[181]The republic was assailed from all sides by slave revolts and Royalist forces,[182]especially the Legion of Hell, an army ofllaneros– the horsemen of theLlanos,to the south – led by the Spanish warlordJosé Tomás Boves.[183]Beginning in February 1814, Boves surged out of the Llanos and overwhelmed the republic, occupying Caracas on 16 July and then destroying Mariño's powerbase on 5 December at theBattle of Urica,where Boves died.[184][185]

As Boves approached Caracas, Bolívar ordered the city stripped of its gold and silver,[186]which was moved through La Guaira toBarcelona, Venezuela,[187]and from there toCumaná.[188]Bolívar then led 20,000 of its citizens east.[186]He arrived in Barcelona on 2 August,[189]but following another defeat at theBattle of Aragua de Barcelonaon 17 August 1814, he moved to Cumaná.[190]On 26 August, he sailed with Mariño toMargarita Islandwith the treasure. The officer in control of the island,Manuel Piar,declared Bolívar and Mariño to be traitors and forced them to return to the mainland.[191]There, Ribas also accused Bolívar and Mariño of treachery, confiscated the treasure,[192]and then exiled the two on 8 September.[193]

Bolívar arrived in Cartagena on 19 September and then met with the New Granadan congress inTunja,[194]which tasked him with subduing the rivalFree and Independent State of Cundinamarca.[195]On 12 December, Bolívar captured Cundinamarca's capital,Bogotá,and was given command of New Granada's armies in January 1815.[196]Bolívar next grappled with del Castillo, who had taken control of Cartagena.[197]Bolívarbesieged the cityfor six weeks. His change of focus allowed the Royalist forces to regain control of the Magdalena.[198]On 8 May, Bolívar made a truce with del Castillo, resigned his command, and sailed for self-exile onJamaicaas a result of this error.[199]In July, 8,000 Spanish soldiers commanded by Spanish generalPablo Morillolanded atSanta Martaand thenbesieged Cartagena,which capitulated on 6 December; del Castillo was executed.[200][201]

Jamaica, Haiti, Venezuela, and New Granada: 1815–1819[edit]

Bolívar arrived inKingston, Jamaica,on 14 May 1815 and,[202]as in his earlier exile on Curaçao, ruminated on the fall of the Venezuelan and New Granadan republics. He wrote extensively, requesting assistance from Britain and corresponding with merchants based in the Caribbean. This culminated in September 1815 with theJamaica Letter,in which Bolívar again laid out his ideology and vision of the future of the Americas.[203]On 9 December, the Venezuelan pirateRenato Beluchebrought Bolívar news from New Granada and asked him to join the Republican community in exile inHaiti.[204]Bolívar tentatively accepted and escaped assassination that night when his manservant mistakenly killed hispaymasteras part of a Spanish plot.[205]He left Jamaica eight days later,[206]arrived inLes Cayeson 24 December,[207]and on 2 January 1816 was introduced toAlexandre Pétion,President of theRepublic of Haitiby a mutual friend.[208]Bolívar and Pétion impressed and befriended each other and,[209]after Bolívar pledged to free every slave in the areas he occupied, Pétion gave him money and military supplies.[210][211]

Returning to Les Cayes, Bolívar held a conference with the Republican leaders in Haiti and was made supreme leader with Mariño as his chief of staff.[212]The Republicans departed Les Cayes for Venezuela on 31 March 1816 and followed theAntilleseastward.[213]After a delay to allow a lover of Bolívar's to join the fleet, it arrived on 2 May at Margarita Island, controlled by Republican commanderJuan Bautista Arismendi.[214]Bolívar next moved to the mainland, where he declared the emancipation of all slaves and annulled of the Decree of War to the Death.[215][e]He seizedCarúpanoon 31 May and sent Mariño and Piar into Guayana to build their own army,[218]then took and heldOcumare de la Costafrom 6 to 14 July, when it was recaptured by the Royalists.[219][220]Bolívar fled by sea toGüiriawhere, on 22 August, he was deposed by Mariño and Venezuelan RepublicanJosé Francisco Bermúdez.[221]

Bolívar returned to Haiti by early September,[222]where Pétion again agreed to assist him.[223]In his absence, the Republican leaders scattered across Venezuela, concentrating in the Llanos, and became disunited warlords.[224]Unwilling to recognize Mariño's leadership,[225]Arismendi wrote to Bolívar and dispatched New Granadan RepublicanFrancisco Antonio Zeato convince him to return. Bolívar and Zea set sail for Venezuela on 21 December withLuis Brión,a Dutch merchant,[226]and arrived ten days later at Barcelona. There, Bolívar announced his return and called for a congress for a new,third republic.[227]He wrote to the Republican leaders, especiallyJosé Antonio Páez,who controlled most of the western Llanos, to unite under his leadership.[228][229]On 8 January 1817, Bolívar marched towards Caracas but was defeated at theBattle of Clarinesand pursued to Barcelona by a larger Royalist force.[230]At Bolívar's request, Mariño arrived on 8 February with Bermúdez, who then reconciled with Bolívar, and forced a Royalist withdrawal.[231]

Even with their combined forces, however, Bolívar, Mariño, and Bermúdez could not hold Barcelona.[232]Instead, on 25 March 1817,[233]Bolívar began moving south to join Piar in Guayana, Piar's power base, and establish his own economic and political base there.[234][235]Bolívar met Piar on 4 April,[236]promoted him to the rank ofgeneral of the army,and then joined a force of Piar's troops besieging the city of Angostura (nowCiudad Bolívar) on 2 May.[237]Meanwhile, Mariño went east to reestablish his power base and on 8 May convened a congress of ten men, including Brión and Zea, that named Mariño as supreme commander of the Republican forces.[238]This backfired and provoked the defection of 30 officers, includingRafael UrdanetaandAntonio José de Sucre,to Bolívar.[239]On 30 June, Bolívar granted Piarleave of absenceat his request,[240]and then issued an arrest warrant on 23 July after Piar began fomenting rebellion, alleging that Bolívar had dismissed him because of hismulattoheritage. Piar was captured on 27 September as he fled to join Mariño and was brought to Angostura, where he was executed byfiring squadon 16 October.[241]Bolívar then sent Sucre to reconcile with Mariño,[242]who pledged loyalty to Bolívar on 26 January 1818.[243]

On 17 July 1817,Angostura fellto Bolívar's forces, which gained control of theOrinoco Riverin early August.[244][245]Angostura became the provisional Republican capital and in September,[246]Bolívar began creating formal political and military structures for the republic.[247][248]Following a meeting atSan Juan de Payaraon 30 January 1818, Páez recognized Bolívar as supreme leader.[249]In February 1818, the Republicans moved north and tookCalabozo,wherethey defeated Morillo,[250]who had returned to Venezuela a year earlier afterconquering Republican New Granada.[251]Bolívar next advanced towards Caracas, but was defeated while en route at theThird Battle of La Puertaon 16 March.[252][253]He escaped assassination by Spanish infiltrators in April. Illness and additional Republican defeats obliged Bolívar to return to Angostura in May. For the rest of the year, he focused on administering the republic, rebuilding its armed forces,[254]and organizing elections for a national congress that would meet in 1819.[255][256]

Gran Colombia: 1819–1830[edit]

Thecongress met in Angosturaon 15 February 1819.[257]There, Bolívar gave a speech in which he advocated for a centralized government modeled on theBritish governmentand racial equality,[258]and relinquished civil authority to the congress.[259]On 16 February, the congress elected Bolívar as president and Zea as vice president.[256][260]On 27 February,[261]Bolívar left Angostura to rejoin Páez in the west andresumed campaigningagainst Morillo, albeit ineffectively.[256][262]In May, as the annualwet seasonwas beginning in the Llanos, Bolívar met with his officers and revealed his intention to invade and liberate New Granada from Royalist occupation,[263]which he had prepared for by sending Santander to build up Republican forces inCasanare Provincein August 1818.[264][265]On 27 May,[266]Bolívar marched with more than 2,000 soldiers toward theAndes[267][268]and left Páez, Mariño, Urdaneta, and Bermúdez to tie down Morillo's forces in Venezuela.[269]

Bolívar entered Casanare Province with his army on 4 June 1819,[270]then met up with Santander atTame, Arauca,on 11 June.[271]The combined Republican force reached theEastern Rangeof the Andes on 22 June and began a grueling crossing.[272]On 6 July, the Republicans descended from the Andes atSochaand into the plains of New Granada.[273]After a brief convalescence, the Republicansmade rapid progressagainst the forces of Spanish colonelJosé María Barreiro Manjónuntil, on 7 August, the Royalists were routed at theBattle of Boyacá.On 10 August, Bolívar entered Bogotá, which the Spanish officials had hastily abandoned,[274][275]and captured the viceregal treasury and armories.[276]After sending forces to secure Republican control of central New Granada,[277]Bolívar paraded through Bogotá on 18 September with Santander.[278]

Desiring to merge New Granada and Venezuela into a "greater republic of Colombia",Bolívar first established a provisional government in Bogotá with Santander,[279]and then left to resume campaigning against the Royalists in Venezuela on 20 September 1819.[280]En route, he learned that Zea had been replaced as vice president in September 1819 by Arismendi, who was conspiring with Mariño against Urdaneta and Bermúdez. Bolívar arrived in Angostura on 11 December and, by being conciliatory, defused the plot.[281]He then proposed the merging of New Granada and Venezuela to the congress on 14 December,[282]which was approved. On 17 December, the congress issued a decree creating the Republic ofColombia,including the regions of Venezuela, New Granada, and the still Spanish-controlledReal Audiencia of Quito,and elected Bolívar and Zea president and vice president respectively.[283]

AfterChristmasDay, 1819,[284]Bolívar left Angostura to direct campaigns against Royalist forces along the Caribbean coasts of Venezuela and New Granada.[285]He met with Santander in Bogotá in March 1820, then rode to Cúcuta and inspected Republican forces in northern Colombia over April and May 1820.[286]Meanwhile, Morillo's military and political position was fatally undermined bythe mutiny of Spanish soldiers in Cádiz on 1 January,which forced Ferdinand VII to accepta liberal constitutionin March.[287][288]News of the mutiny and its consequences arrived in Colombia in March and was followed by orders from Spain to Morillo to publicize the constitution and negotiate a peace that would return Colombia to the Spanish Empire. Bolívar and Morillo, seeking to gain leverage over each other,[289]delayed talks until 21 November, when Colombian and Royalist delegates met inTrujillo, Venezuela.[290]The delegates completedtwo treatieson 25 November, establishing a six-month truce, aprisoner exchange,andbasic rights for combatants.Bolívar and Morillo signed the treaties on 25 and 26 November, then met the next day atSanta Ana de Trujillo.[291][292]After this meeting, Morillo turned his command over to Spanish generalMiguel de la Torreand departed for Spain on 17 December.[293]

In February 1821, as Bolívar was traveling from Bogotá to Cúcuta in anticipation of the opening ofa new congress there,[294]he learned that Royalist-controlled Maracaibo had defected to Colombia and been occupied by Urdaneta.[295][296]La Torre protested to Bolívar, who refused to return Maracaibo, leading to a renewal of hostilities on 28 April.[297]Over May and June, Colombia's armies made rapid progress until, on 24 June, Bolívar and Páez decisively defeated La Torre at theBattle of Carabobo.[298][299]All Royalist forces remaining in Venezuela were eliminated by August 1823.[300]Bolívar entered Caracas in triumph on 29 June,[301]and issued a decree on 16 July dividing Venezuela into three military zones governed by Páez, Bermúdez, and Mariño.[302]Bolívar then met with the Congress of Cúcuta,[303]which had ratified the formation of Gran Colombia and elected him as president and Santander as vice president in September. Bolívar accepted and was sworn in on 3 October, although he protested the establishment of a precedent of military leaders as head of the Colombian state.[304]

Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia: 1821–1826[edit]

After the Battle of Carabobo, Bolívar turned his attention south, toPasto, Colombia;Quito and theFree Province of Guayaquil,Ecuador;and theViceroyalty of Peru.Pasto and Quito were Royalist strongholds,[300][305]while Guayaquil had declared its independence on 9 October 1820[306]and had been garrisoned by Sucre on Bolívar's orders in January 1821.[307]Panamadeclared its independence on 28 November 1821 and joined Colombia.[308]Peru had been invaded bya Republican armyled by Argentine generalJosé de San Martín,who hadliberated Chileand Peru,[309]and Bolívar feared San Martín would absorb Ecuador into Peru.[310]In October 1821, after congress empowered him to secure Ecuador for Colombia,[311]Bolívar assembled an army in Bogotá that departed on 13 December 1821.[312]His advance was halted by illness and aPyrrhic victoryat theBattle of Bombonáin southern Colombia on 7 April 1822.[313][314]

To the south, Sucre, who had been trapped in Guayaquil by Royalist advances from Quito,[315]now advanced, decisively defeated the Royalists at theBattle of Pichinchaon 24 May 1822, and occupied Quito.[313][316]On 6 June, Pasto surrendered,[317]and ten days later Bolívar paraded through Quito with Sucre.[318]He also met the Ecuadorian RepublicanManuela Sáenz,the wife of a British merchant, with whom he began a lasting affair.[319]From Quito, Bolívar traveled to Guayaquil in anticipation of a meeting with San Martín to discuss the city's status and to rally support for its annexation by Colombia.[320]When San Martín arrived in Guayaquil on 26 July,[321]Bolívar had already secured Guayaquil for Colombia,[322]and the two-dayGuayaquil Conferenceproduced no agreement between Bolívar and San Martín. Ill, politically isolated, and disillusioned, San Martín resigned from his offices and went into exile.[323][324]

Over the rest of 1822, Bolívar traveled around Ecuador to complete its annexation while dispatching officers to suppress repeated rebellions in Pasto and resisting calls to return to Bogotá or Venezuela.[325]Meanwhile, Royalist forces under generalJosé de Canteracoverwhelmed the Peruvian republic.[326][327]After initially refusing Colombian assistance,[328]thePeruvian congressasked Bolívar several times in 1823 to assume command of their forces. Bolívar responded by sending an army under Sucre to assist,[329]then delayed his own departure to Peru until he obtained permission from the Colombian congress on 3 August.[330]When Bolívar arrived inLima,Peru's capital, on 1 September,[331]Peru was split between two rival presidents,José de la Riva AgüeroandJosé Bernardo de Tagle,and the Royalists under theViceroy of Peru,José de la Serna.[332][333]

In November 1823, Riva Agüero, who plotted with the Royalists against Bolívar, was betrayed by his officers to Bolívar and exiled from Peru.[334]While Bolívar was bedridden with fever over the first two months of 1824, Tagle defected to the Royalists with the garrison and city ofCallaoand briefly took Lima.[335]In response, the Peruvian congress named Bolívar dictator of Peru on 10 February 1824. Bolívar moved to northern Peru in March and began assembling an army.[333][336]His repeated demands for additional men and money strained his relationship with Santander.[337]

In May 1823, conservative Royalist generalPedro Antonio Olañeta,based in the region ofUpper Peru,rebelledagainst la Serna. Bolívar seized the opportunity to advance into theJunín region,where he defeated Canterac at theBattle of Junínon 6 August, driving them out of Peru.[338][339]Choosing to ignore Olañeta, la Serna ordered his forces to concentrate atCuzcoto face Bolívar.[339][340]Heavy rainfall in September halted Bolívar's advance,[341]and on 6 October he gave command of the army to Sucre and moved toHuancayoto manage political affairs.[342]

On 24 October, Bolívar received a letter from Santander informing him that because he had accepted the dictatorship of Peru the Colombian congress had stripped him of his military and civil authority in favor of Sucre and Santander, respectively.[342]Although indignant and resentful of Santander, Bolívar wrote to him on 10 November to communicate his acquiescence[343]and reoccupied Lima on 5 December 1824.[344]On 9 December, Sucre decisively defeated La Serna's Royalists at theBattle of Ayacuchoand acceptedthe surrenderof all Royalist forces in Peru. The garrison of Callao and Olañeta ignored the surrender. Shortly after arriving in Lima, Bolívar begana siege of Callaothat lasted until January 1826,[345][346]and sent Sucre into Upper Peru to eliminate Olañeta. However, Oleñeta was killed at theBattle of Tumuslaprior to Sucre's arrival. With Irish volunteerFrancisco Burdett O'Connorserving as his second in command, Sucre completed the liberation of Upper Peru in April 1825.[347]

In early 1825, Bolívar resigned from his offices in Colombia and Peru, but neither nation's congress accepted his resignation; on 10 February 1825, the Peruvian congress extended his dictatorship for another year. Accepting the extension,[348]Bolívar settled into governing Peru and passing reforms that were largely not carried out, such as a school system based on the principles of English educatorJoseph Lancasterthat was managed by Simón Rodríguez.[349]In April 1825, Bolívar began a tour of southern Peru that took him to the cities ofArequipaand Cuzco by August. As Bolívar approached Upper Peru, a congress gathered in the city of Chuquisaca (nowSucre); on 6 August, itdeclaredthe region to be the nation ofBolivia,named BolívarPresident,and asked him to write a constitution for Bolivia.[350]Bolívar arrived inPotosíon 5 October and met with two Argentine agents,Carlos María de AlvearandJosé Miguel Díaz Vélez,who tried without success to convince him to intervene in theCisplatine Waragainst theEmpire of Brazil.[351]

From Potosí, Bolívar traveled to Chuquisaca and appointed Sucre to govern Bolivia on 29 December 1825;[352]he departed for Peru on 1 January 1826.[353]Bolívar arrived in Lima on 10 February and dispatched his draft of the Bolivian constitution to Sucre on 12 May.[354]That constitutionwas ratified with modification by the Bolivian congress in July 1826.[355]Peru, whose elites chafed at Bolívar's rule and the presence of his soldiers, was also induced to accepta modified versionof Bolívar's constitution on 16 August.[356]In Venezuela,Páez revolted against Santander,and in Panama,a congress of American nationsorganized by Bolívar convened without his attendance and produced no change in the hemisphericstatus quo.On 3 September, responding to pleas for his return to Colombia, Bolívar departed Peru and left it under a governing council led by Bolivian generalAndrés de Santa Cruz.[357]

Final years: 1826–1830[edit]

Bolívar arrived in Guayaquil on 13 September 1826 and heard complaints against Santander's governance from the people of Guayaquil and Quito, who declared him their dictator.[358]From Ecuador, he continued north and heard more complaints, promoted civil and military officers, and commuted prison sentences.[359]As he approached Bogotá, Bolívar was met by Santander, who hoped to persuade Bolívar to his cause in the conflict with Páez. Although Santander was annoyed at Bolívar for his desire to return to power and ratify a version of the Bolivian constitution in Colombia, they reconciled and agreed that Bolívar would resume the presidency of Colombia; congress had reelected them to a second four-year term beginning on 2 January 1827. Bolívar arrived in Bogotá on 14 November 1826.[360]

On 25 November, Bolívar left Bogotá with an army supplied by Santander and arrived at Puerto Cabello on 31 December,[361]where he issued a general amnesty to Páez and his allies if they submitted to his authority. Páez accepted and in January 1827, Bolívar confirmed Páez's military authority in Venezuela and entered Caracas with him to much jubilation; for two months, Bolívar attendedballscelebrating his return and the amnesty.[362]That amnesty, and clashes over Santander's handling of Colombia's finances, caused a break between Bolívar and Santander that became an open enmity in 1827.[363]In February 1827, Bolívar submitted his resignation from the Presidency of Colombia, which its congress rejected.[364]Meanwhile, the Colombian soldiers garrisoned in Lima mutinied, arrested their Venezuelan officers, andoccupied Guayaquil until September 1827,allowing Bolívar's opponents in Peru to depose him as president and repeal his constitution.[365]

Bolívar departed Venezuela to return to Bogotá in July 1827. He arrived on 10 September with an army he had gathered at Cartagena and secured the calling of a new congress to meet at the city ofOcañain early 1828 to modify the Colombian constitution. The elections for this congress were held in November 1827 and, as Bolívar declined to campaign because he did not wish to be perceived as personally influencing the elections, were very favorable to his political opponents.[366]In January 1828, Bolívar was joined in Bogotá by Sáenz,[367]but on 16 March 1828 he left the capital after being informed of a Spanish-backed rebellion in Venezuela. As that revolt was crushed before he arrived, Bolívar turned his attention to the occupation of Cartagena byJosé Prudencio Padilla,a New Granadan admiral and Santander loyalist. Padilla's rebellion was also crushed before Bolívar arrived, however, and he was arrested and imprisoned in Bogotá. As theConvention of Ocañaopened on 9 April, Bolívar based himself atBucaramangato monitor its proceedings through his aides.[368]

The convention appeared likely to adopt a federalist system. To prevent this, on 11 June 1828 Bolívar's allies staged awalkout,leaving the convention without aquorum.[369]Two days later,Pedro Alcántara Herrán,a Bolívar loyalist and the governor of New Granada, called a meeting of the city's elite that denounced the Convention of Ocaña and called on Bolívar to assume absolute power in Colombia. Bolívar returned to Bogotá on 24 June and on 27 August assumed supreme power as the "president-liberator" of Colombia, abolished the office of the vice president, and assigned Santander to a diplomatic posting in Washington, D.C. On 25 September 1828, a group of young liberals that included Santander's secretary madean attempt to assassinate Bolívarand overthrow his government. The attempt was thwarted by Sáenz, who bought time for Bolívar to escape as the assassins entered thePalacio de San Carlos,and the Colombian Army. Bolívar spent the night hiding under a bridge until soldiers loyal to his regime rescued him.[370]

In the aftermath of the attempted coup, Santander and the conspirators were arrested. Bolívar, depressed and ill, considered resigning from politics and pardoning the conspirators, but was dissuaded from this by his officers. Padilla, though uninvolved with the attempted coup, was executed for treason for his earlier rebellion; Santander, whom Bolívar thought responsible for the plot, was pardoned but exiled from Colombia.[371]In December 1828, Bolívar left Bogotá to respond to Peru'sintervention in Boliviaandinvasion of Ecuadorand a revolt in Popayán and Pasto led byJosé María Obando.He left behind a council of ministers led by Urdaneta to govern Colombia and announced that a congress would convene in January 1830 to devise a new constitution. Over 1829, Obando was defeated by Colombian generalJosé María Córdovaat Bolívar's direction in January and then pardoned, while Sucre and Venezuelan generalJuan José Floresdefeated the Peruvians at theBattle of Tarquiin February, leading to an armistice in July and then theTreaty of Guayaquilin September.[372]

While Bolívar was away, Urdaneta and the council of ministers planned with French envoys to have a member of theHouse of Bourbonsucceed Bolívar on his death as King of Colombia. This plan was widely unpopular, and inspired Córdova to launch a revolt that was crushed in October 1829 byDaniel Florence O'Leary,Bolívar'saide-de-camp.In November, Bolívar ordered the council to cease its planning; instead they resigned.[373]Venezuelans, encouraged by a circular letter Bolívar had published in October, voted to secede from Colombia.[374]On 15 January 1830, Bolívar arrived in Bogotá and on 20 January theAdmirable Congressconvened in the city. Bolívar submitted his resignation from the presidency, which the congress did not accept until 27 April, following the appointment of New Granadan politicianDomingo Caycedoas interim President.[375]

Death and burial[edit]

Determined to go into exile, Bolívar, who had given away or lost his fortune over his career, sold most of his remaining possessions and departed from Bogotá on 8 May 1830.[376]He traveled down the Magdalena to Cartagena, where he arrived by the end of June to wait for a ship to take him to England.[377]On 1 July, Bolívar was informed that Sucre had been assassinated near Pasto while en route to Quito, and wrote to Flores to ask him to avenge Sucre.[378]In September, Urdaneta installed a conservative government in Bogotá and asked Bolívar to return, but he refused.[379]With his health deteriorating and no ship forthcoming, Bolívar was moved by his staff toBarranquillain October and then, at the invitation of a Spanish landowner in the area, to theQuinta de San Pedro Alejandrinonear Santa Marta. There, on 17 December 1830, at the age of 47, Bolívar died oftuberculosis.[380]

Bolívar's body, dressed in a borrowed shirt, was interred in theCathedral Basilica of Santa Martaon 20 December 1830.[381]In 1842, Páez secured the repatriation of Bolívar's remains, which were paraded through Caracas and then laid to rest in its cathedral in December together with his wife and parents; Bolívar's heart remained in Santa Marta. His remains were moved again in October 1876 into theNational Pantheon of Venezuelain Caracas, created that year byPresidentAntonio Guzmán Blanco.[382]

Bolívar's death has been the subject of conspiracy theories advanced by theUnited Socialist Party of Venezuela.In January 2008, PresidentHugo Chávezset up a commission to investigate his claim that Bolívar had been poisoned by "New Granada traitors."[383][384]The commission exhumed Bolívar's remains on 16 July 2010.[385]The results, made public on 26 July 2011, were inconclusive;Vice President of VenezuelaElías Jauaannounced that the commission could not prove Chávez's claim.[386][387][388]Chávez continued to claim that Bolívar had been assassinated viaarsenic poisoning,citing a paper by infectious disease specialist Paul Auwaerter. Following Chávez's remarks, Auwaerter stated that the arsenic likely came from medicines Bolívar had ingested to treat his illnesses.[386][389][390]

Personal beliefs[edit]

| Part of thePolitics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Bolívar's personal beliefs were liberal andrepublican,and formed byClassicalandEnlightenment philosophy;[391]among his favorite authors wereHobbes,Spinoza,theBaron d'Holbach,Hume,Montesquieu,andRousseau.[21]The tutelage of Simón Rodríguez, a student of Rousseau, has been traditionally seen as foundational for Bolívar's beliefs.[32][392]Also important to Bolívar's intellectual development were his stays in Paris from 1804 to 1806 and in London in 1810.[393][394]Bolívar was ananglophile,and sought British aid in securing Latin American independence.[395][396]The extent of Bolívar's religiosity is debated; while Bolívar resented the social capital of theCatholic Churchand its Royalist leanings during the wars of independence, he sought to co-opt its social capital for the benefit of the republics he established rather than dismember the Church.[397][398]

Throughout his political career, Bolívar concerned himself with the construction of liberal democracy in Latin America and the region's place in the Atlantic world.[399]By the 1820s, his goal was to create a federation of Latin American republics in Spanish America, each governed by a strong executive and a constitution modeled on theBritish constitution.[400]Inspired by Montesquieu, Bolívar believed that a government should conform to the needs and character of its region and inhabitants;[401]in the Cartagena Manifesto, Bolívar stated that federalism as practiced in the United States was the "perfect" government but was unworkable in Spanish America because, he believed, Spanish imperialism had left Spanish Americans unprepared for federalism.[402][403]Bolívar sought to prepare Colombia for a more liberal democracy via free, public education.[404]Over the 1820s, Bolívar became increasingly disillusioned and authoritarian until, in 1830, he declared to Flores, "all who have served the Revolution have plowed the sea."[405]

Legacy[edit]

Bolívar is the preeminent symbol of Latin America and the focus of what could seem almost unrivaled posthumous attention, seen from his own times forward as a force now for liberalism or other forms of modernity, now for old regime values and authoritarianism, now for a mix of the two, with the debate over the meaning of his figure having no end in sight.

Robert T. Conn,Bolívar's Afterlife in the Americas[406]

Bolívar has had an immense legacy, becoming the essential personality of Latin America.[406][407]The currencies of Venezuela and Bolivia—thebolívarandbolivianorespectively—are named after Bolívar.[408][409]In the English-speaking world, Bolívar is known as Latin America'sGeorge Washington.[410]He has been memorialized across the world in literature, public monuments, and historiography, and paid tribute to in the names of towns, cities, provinces, and other people.[411][412]The Quinta near Santa Marta has been preserved as a museum to Bolívar[413]andthe house in which he was bornwas opened as a museum and archive of his papers on 5 July 1921.[414]In 1978,UNESCOcreated theInternational Simón Bolívar Prize"to reward an activity of outstanding merit in accordance with the ideals of Simón Bolívar."[415]

Initial historical evaluations of Bolívar were at first negative, consisting of criticism of his conduct of the war, execution of Piar, betrayal of Miranda, and authoritarianism.[416]These and other criticisms endure in studies of Bolívar.[417]Beginning in 1842, however, popular opinion about Bolívar in Venezuela became overwhelmingly positive and eventually became what has been described by scholars as the "cult of Bolívar", led by succeeding heads of the Venezuelan state. In 1998, PresidentHugo Chávez,who had made extensive use of Bolívar's image for government projects and initiatives, changed the official name of Venezuela to theBolivarian Republic of Venezuela.[418]In Colombia, allegiance or opposition to Bolívar formed the bedrock of theConservativeandLiberalparties respectively.[419]Bolívar continued to have such a cultural influence in Colombia that in 1974 the19th of April Movement,an insurgent leftist group that later joined an alliance thereof called theSimón Bolívar Guerrilla Coordinating Board,stole a swordalleged to belong to Bolívar from hisBogotá residence.[420][421]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Styledas Supreme Political and Military Authority of the Peruvian Republic.[1]

- ^Styled as Liberator President of the Republic of Colombia, Liberator of Peru, and Charged with the Supreme Command of it. The term "president" was not in common use at the time of Bolívar's designation. Whether this then makes Bolívar not the first president is a minor source of academic dispute.[2]

- ^English:/ˈbɒlɪvər,-vɑːr/BOL-iv-ər, -ar;[3]US:/ˈboʊlɪvɑːr/BOH-liv-ar;[4]Spanish:[siˈmomboˈliβaɾ].In isolation,Simónis pronounced as Spanish[siˈmon],and that is the pronunciation in the recording.

- ^Biographers disagree on the exact date Miranda arrived in Venezuela in December 1810. Arana says 10 December,[107]Lynch says 11 December,[108]Masur and Langley say 12 December,[109][110]Slatta and de Grummond say 13 December.[111]

- ^Masur, Langley, and Arana state that Bolívar issued his proclamation of emancipation in early June.[216]Slatta, de Grummond, and Lynch state that it was issued in July.[217]

Notes[edit]

- ^"Ley Disponiendo Que El Ejecutivo Comunique A Bolívar La Abolición De La Constitución Vitalicia Y La Elección De Presidente De La República, 22 de Junio de 1827"(in Spanish).Congress of Peru.22 June 1827.Retrieved29 March2023.

- ^"Se enciende el debate por el cargo de Simón Bolívar"[Debate Ignites over Simón Bolívar's Position].El Día(in Spanish). Santa Cruz de la Sierra. 19 December 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 14 February 2023.Retrieved14 February2023.

- ^"Bolívar".Collins English Dictionary.HarperCollins.Archived fromthe originalon 31 May 2019.Retrieved21 August2019.

- ^"Bolívar, Simón".Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English.Longman.Archived fromthe originalon 21 August 2019.Retrieved21 August2019.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 20, 22;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 311;Lynch 2006,p. 2;Langley 2009,p. 4;Arana 2013,pp. 6–8.

- ^Langley 2009,p. 4.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 20;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 10;Arana 2013,pp. 8–9.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 20;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 10–11;Langley 2009,p. 4.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 20;Langley 2009,p. 4;Arana 2013,pp. 7, 17.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 7.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 311;Langley 2009,p. xix;Arana 2013,p. 21.

- ^Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,p. 18.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 23;Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,p. 18.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 11.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 22–23.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 22–23;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 11–12;Lynch 2006,p. 16;Arana 2013,pp. 7–8, 22.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 12;Langley 2009,p. xix.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 23;Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,p. 24.

- ^abArana 2013,p. 25.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 23;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 13;Arana 2013,p. 24.

- ^abSlatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 13.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 24;Arana 2013,p. 25.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 17.

- ^Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,p. 25.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 23–24;Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,p. 22.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 23–24;Langley 2009,p. 9;Arana 2013,pp. 22–23.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 17;Arana 2013,p. 32.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 25;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 14;Lynch 2006,p. 17;Arana 2013,p. 32.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 32.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 25;Lynch 2006,p. 17;Arana 2013,p. 33.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 25;Arana 2013,p. 34.

- ^abMasur 1969,pp. 24–25;Lynch 2006,pp. 16–17;Arana 2013,pp. 34–35.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 27;Lynch 2006,p. 17;Arana 2013,pp. 36–37.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 27;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 17;Lynch 2006,p. 18;Arana 2013,p. 37.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 18;Arana 2013,p. 37.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 17;Arana 2013,p. 42.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 27;Lynch 2006,p. 18;Arana 2013,p. 38.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 37.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 18;Lynch 2006,p. 18.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 18;Arana 2013,p. 43.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 18;Lynch 2006,p. 19;Arana 2013,p. 43.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 28;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 18;Langley 2009,p. 13;Arana 2013,p. 44.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 44.

- ^Cardozo Uzcátegui 2011,pp. 17–18.

- ^Cardozo Uzcátegui 2011,pp. 14, 19.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 28;Langley 2009,p. 13;Arana 2013,p. 44.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 19;Arana 2013,p. 46.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 30;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 18;Arana 2013,p. 46.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 30–31;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 19;Langley 2009,p. 13.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 30;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 18–19;Arana 2013,pp. 46–47.

- ^abcLynch 2006,p. 20.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 20;Arana 2013,p. 47.

- ^Cardozo Uzcátegui 2011,p. 18.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 19;Arana 2013,p. 47.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 31;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 19;Lynch 2006,p. 20.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 20;Arana 2013,p. 48.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 48.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 19;Lynch 2006,p. 20;Arana 2013,pp. 49–50.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 31;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 19–20;Lynch 2006,p. 21;Langley 2009,p. 14;Arana 2013,pp. 50–51.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 51.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 19–20;Lynch 2006,p. 22;Arana 2013,p. 51.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 33–34;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 20;Lynch 2006,p. 22;Langley 2009,p. 15;Arana 2013,pp. 51–52.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 52.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 20;Langley 2009,p. 15.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 20;Arana 2013,p. 52.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 23;Arana 2013,pp. 53–54.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 36–37;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 21–22;Lynch 2006,p. 23;Langley 2009,p. 15;Arana 2013,pp. 54, 57–58.

- ^Bushnell 2003,p. 114;Brown 2009,p. 4.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 24;Lynch 2006,p. 25;Arana 2013,p. 61.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 41;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 24;Lynch 2006,p. 25;Arana 2013,pp. 61–62.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 24;Arana 2013,p. 62.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 41;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 24;Lynch 2006,p. 26;Arana 2013,p. 63.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 41–42;Arana 2013,pp. 63, 65.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 24;Lynch 2006,p. 26;Arana 2013,pp. 65–66.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 27.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 55–56;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 30;Lynch 2006,p. 39;Arana 2013,p. 70.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 25;Arana 2013,p. 71.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 25;Lynch 2006,p. 39;Arana 2013,p. 72.

- ^Langley 2009,p. 18.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 26;Arana 2013,p. 77.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 33–34;Lynch 2006,p. 41;Arana 2013,p. 80.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 41;Arana 2013,pp. 77, 81.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 61–62;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 26–27;Lynch 2006,p. 44;Arana 2013,pp. 77–78.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 31–32;Lynch 2006,p. 45;Arana 2013,p. 79.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 45–46;Arana 2013,pp. 79–80.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 33–34;Lynch 2006,pp. 46–47.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 65–66;Lynch 2006,p. 46;Arana 2013,p. 81.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 35;Lynch 2006,p. 47;Arana 2013,pp. 82–83.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 35;Lynch 2006,p. 47;Arana 2013,pp. 83–84.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 67;Arana 2013,p. 84.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 68–69;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 36–37;Arana 2013,pp. 84–86.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 48;Arana 2013,p. 86.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 85.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 38;Lynch 2006,p. 48.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 38;Lynch 2006,p. 48;Arana 2013,p. 87.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 38.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 72–73;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 38;Lynch 2006,pp. 48–49;Langley 2009,p. 28;Arana 2013,pp. 87–88.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 49–50;Arana 2013,p. 92.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 39–40;Lynch 2006,pp. 51–52;Arana 2013,pp. 88–90.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 77;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 40;Lynch 2006,pp. 52–53.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 50;Langley 2009,pp. 30–31;Arana 2013,pp. 93–94.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 53;Arana 2013,p. 95.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 41;Langley 2009,p. 31;Arana 2013,p. 95.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 41;Lynch 2006,p. 53;Arana 2013,p. 95.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 80–81;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 41;Lynch 2006,pp. 53–54.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 41–42;Lynch 2006,p. 54;Arana 2013,pp. 96–97.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 95.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 54.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 85.

- ^Langley 2009,p. 32.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 42.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 54;Langley 2009,p. 31.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 87.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 83;Langley 2009,p. 31.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 84;Langley 2009,p. 31.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 87–88.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 46;Arana 2013,p. 97.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 86;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 46.

- ^Arana 2013,p. 100.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 87–88;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 47;Lynch 2006,p. 55;Langley 2009,p. 33;Arana 2013,pp. 100–101.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 88;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 47;Arana 2013,p. 101.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 88–91.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 56.

- ^Arana 2013,pp. 99–100.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 58;Arana 2013,p. 100.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 91;Arana 2013,p. 104.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 91.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 91;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 48;Langley 2009,p. 34;Langley 2009,p. 34;Arana 2013,p. 104.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 92;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 48, 52;Lynch 2006,p. 58;Arana 2013,pp. 104–105.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 92;Arana 2013,p. 105.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 93;Arana 2013,pp. 105–106.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 1.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 91–92.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 55;Lynch 2006,p. 59;Langley 2009,pp. 35–36;Arana 2013,pp. 107–109.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 96.

- ^Arana 2013,pp. 108–109.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 95–96;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 56;Lynch 2006,p. 59;Arana 2013,pp. 109–110.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 57.

- ^abcMcFarlane 2014,p. 93.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 97–98;Lynch 2006,p. 60;Arana 2013,p. 112.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 57;Arana 2013,p. 112.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 57;Lynch 2006,p. 60;Arana 2013,p. 112.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 100;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 58;Arana 2013,pp. 114–115.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 101;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 58–59;Arana 2013.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 103;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 63;Arana 2013,p. 118.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 64;Lynch 2006,p. 61;Arana 2013,p. 119.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 61;Arana 2013,p. 118.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 103–104;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 64–65;Lynch 2006,pp. 61–62;Arana 2013,pp. 120–122.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 104–105;Lynch 2006,p. 62;Arana 2013,p. 122.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 105;Langley 2009,p. 38.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 105;Arana 2013,p. 122.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 105–106;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 67;Lynch 2006,pp. 62–63;Arana 2013,pp. 124–126.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 67;Langley 2009,p. 42;Arana 2013,pp. 126–128.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 107, 112;Arana 2013,p. 128.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 71;Arana 2013,pp. 129, 132.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 113–115;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 70;Lynch 2006,pp. 66–68;Arana 2013,pp. 130–131.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 116.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 116;Lynch 2006,p. 69;Arana 2013,pp. 131–132.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 116–117;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 71–72;Lynch 2006,pp. 69–70;Arana 2013,pp. 132–133.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 118–119;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 72–73;Arana 2013,pp. 136–138.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 73–74;Lynch 2006,p. 70.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 119;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 74;Arana 2013,p. 138.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 119–120;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 74–76;Lynch 2006,pp. 70–71;Arana 2013,pp. 138–139.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 75.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 124;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 77;Lynch 2006,p. 73;Langley 2009,p. 46;Arana 2013,pp. 142–143.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 115.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 129;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 75;Lynch 2006,p. 75;Arana 2013,p. 146.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 120.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 82–84;Lynch 2006,p. 84.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 123.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 84–85;Lynch 2006,p. 79.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 122–123;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 76;Lynch 2006,p. 72;Arana 2013,p. 140.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 77.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 125.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 77–78.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 122.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 138–139;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 75, 85;Lynch 2006,pp. 76–78.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 118–119.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 140;Langley 2009,p. 47;Arana 2013,p. 150.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 135;Langley 2009,p. 49.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 86;Langley 2009,pp. 48–49;Arana 2013,p. 153.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 123–124.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 85–87, 97;Lynch 2006,pp. 81–82;Arana 2013,pp. 151–152.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 100–104, 106–112;Langley 2009,p. 50;Arana 2013,pp. 156–159, 163–164.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 126–129.

- ^abMasur 1969,p. 161;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 106;Lynch 2006,p. 86;Arana 2013,p. 159.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 107.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 162.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 108;Arana 2013,p. 160.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 161–162;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 108;Lynch 2006,pp. 86–87;Arana 2013,p. 161.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 108–109;Lynch 2006,p. 87.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 109;Lynch 2006,p. 87;Arana 2013,pp. 162–163.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 163;Arana 2013,p. 163.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 165–166;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 110–111;Lynch 2006,p. 88.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 167;Lynch 2006,p. 89;Langley 2009,p. 54.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 111–113;Lynch 2006,pp. 88–89;Arana 2013,p. 168.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 168–170;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 113–114;Lynch 2006,pp. 89–90;Langley 2009,p. 55;Arana 2013,pp. 169–170.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 114;Lynch 2006,pp. 89–90;Arana 2013,pp. 169–170.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 170–171;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 114;Langley 2009,p. 55;Arana 2013,pp. 170–171.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 173–174;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 115;Lynch 2006,p. 90;Arana 2013.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 138.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 116;Lynch 2006,p. 90.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 184–185, 190;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 124–127;Lynch 2006,pp. 92, 95;Langley 2009,pp. 55–57;Arana 2013,pp. 174–176.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 128–129.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 183;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 129;Lynch 2006,pp. 96–97;Arana 2013,p. 177.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 191;Lynch 2006,p. 97;Arana 2013,pp. 177–178.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 129;Langley 2009,p. 59;Arana 2013,p. 178.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 192;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 130;Lynch 2006,p. 97;Langley 2009,p. 59;Arana 2013,pp. 178–179.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 192–193;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 130;Arana 2013,p. 179.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 193;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 130;Lynch 2006,p. 97;Arana 2013,p. 179.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 313.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 194–195;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 131–132;Arana 2013,p. 179.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 195;Lynch 2006,p. 100;Arana 2013,p. 183.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 137–138;Lynch 2006,p. 100;Arana 2013,pp. 183–184.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 197–198;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 141–142;Lynch 2006,p. 100;Langley 2009,p. 60;Arana 2013,p. 186.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 197;Langley 2009,p. 60;Arana 2013,p. 186.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 142;Lynch 2006,p. 100.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 197;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 139–140.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 198–200;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 141–144;Lynch 2006,p. 100.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 314.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 202;Lynch 2006,p. 101;Arana 2013,p. 189.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 147–148;Arana 2013,p. 190.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 203;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 146;Lynch 2006,p. 101;Arana 2013,p. 189.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 146;Arana 2013,pp. 190–191.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 203;Arana 2013,p. 191.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 203;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 150–151;Arana 2013,pp. 190–191.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 151–152;Lynch 2006,p. 102.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 146–147;Lynch 2006,p. 102;Arana 2013,pp. 191–192.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 313–315.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 152;Arana 2013,p. 192.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 208–209;Arana 2013,pp. 192–193.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 153;Lynch 2006,p. 102;Arana 2013,p. 193.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 210;Arana 2013,p. 195.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 207–208;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 153;Lynch 2006,pp. 102–103;Arana 2013,p. 193.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 315.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 210;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 154.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 211;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 155;Lynch 2006,pp. 103–104;Arana 2013,pp. 195–196.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 211, 213;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 153–154, 156;Arana 2013,pp. 200–202.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 213–214;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 156;Lynch 2006,p. 104;Arana 2013,p. 202.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 217;Lynch 2006,p. 106;Arana 2013,p. 197.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 217–218;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 158–160;Arana 2013,pp. 197–199.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 220;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 160;Arana 2013,pp. 202–203.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 160.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 215;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 157;Arana 2013,p. 201.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 317–318.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 163.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 163;Lynch 2006,pp. 110–112.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 319.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 113–114;Arana 2013,p. 207.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 231–232;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 171–172;Lynch 2006,p. 115;Arana 2013,pp. 209–211.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 317.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 234–235;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 173;Lynch 2006,p. 116;Arana 2013,pp. 211–212.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 321–322.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 235–237, 243;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 174–180;Lynch 2006,pp. 116–117;Arana 2013,pp. 212–217.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 244;Lynch 2006,p. 117.

- ^abcMcFarlane 2014,p. 325.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 245;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 180;Lynch 2006,p. 119;Arana 2013,p. 222.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 246–253;Lynch 2006,pp. 120–122;Arana 2013,pp. 222–225.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 246;Arana 2013,p. 222.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 254;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 180;Arana 2013,p. 225.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 255.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 255–258;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 180–181;Lynch 2006,p. 126;Arana 2013,pp. 226–228.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 263;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 183;Lynch 2006,p. 127;Arana 2013,pp. 228–229.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 176;Lynch 2006,p. 124.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 324–325.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 183;Lynch 2006,p. 127.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 127;Langley 2009,p. 75;Arana 2013,p. 228.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 326–327.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 127;Arana 2013,pp. 229–230.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 184;Arana 2013,p. 230.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 264;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 184;Lynch 2006,p. 128;Arana 2013,pp. 230–231.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 166;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 185.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 128;Arana 2013,p. 232.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 268–273;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 188–193;Lynch 2006,pp. 128–130;Langley 2009,p. 75;Arana 2013,pp. 232–235.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 327–328.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 193;Lynch 2006,p. 130;Arana 2013,pp. 235, 237.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 276;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 193, 195;Lynch 2006,pp. 130–131.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 280;Lynch 2006,p. 130;Arana 2013,pp. 238–239.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 277, 280;Lynch 2006,p. 131;Arana 2013,pp. 240–241.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 195;Lynch 2006,pp. 131–132.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 282–283;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 196–197;Lynch 2006,pp. 132–133;Arana 2013,pp. 245–246.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 283;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 197–198;Arana 2013,p. 246.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 284;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 198;Lynch 2006,p. 134;Arana 2013,pp. 246–247.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 290;Arana 2013,p. 247.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 290;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 200–201;Arana 2013,p. 247.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 201–202;Lynch 2006,pp. 134, 136.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 291–292;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 204;Lynch 2006,p. 136;Arana 2013,pp. 247–248.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 368.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 292–297;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 204–209;Lynch 2006,pp. 136–137;Arana 2013,pp. 248, 253–254.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 297;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 209;Arana 2013,p. 254.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 297;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 209–210;Lynch 2006,p. 137;Arana 2013,pp. 254–255.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 388–389.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 211;Lynch 2006,p. 138;Arana 2013,p. 257.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 303;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 216.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 302–303;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 216;Lynch 2006,p. 139.

- ^McFarlane 2014,p. 391.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 304;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 218;Arana 2013,p. 263.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 304–307;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 218–220;Lynch 2006,pp. 139–140;Arana 2013,pp. 263–265.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 391–392.

- ^abMcFarlane 2014,p. 392.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 221;Arana 2013,p. 267.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 141–142;Arana 2013,p. 266.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 221;Arana 2013,p. 271.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 308–310;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 221;Lynch 2006,pp. 145–146;Arana 2013,p. 271.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 313–314;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 224;Lynch 2006,p. 167.

- ^Lynch 2006,p. 167.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 302, 319;Lynch 2006,pp. 138–139, 168.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 317;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 222;Lynch 2006,p. 167.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 213–215;Langley 2009,p. 79;Arana 2013,pp. 271–277.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 317;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 224–225;Lynch 2006,p. 167;Arana 2013,p. 278.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 312;Lynch 2006,p. 146.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 321;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 221;Lynch 2006,pp. 146, 168;Arana 2013,pp. 278–279.

- ^abMcFarlane 2014,p. 393.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 323–325;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 226;Lynch 2006,p. 169;Arana 2013,pp. 281–283.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 320;Lynch 2006,p. 168;Arana 2013,p. 280.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 325;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 226–227;Lynch 2006,p. 170;Langley 2009,pp. 80–81;Arana 2013,pp. 28–88.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 325–326;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 227.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 327;Lynch 2006,pp. 170–171;Arana 2013,pp. 287–288.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 327;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 228, 230;Lynch 2006,pp. 171, 178–179;Langley 2009,p. 81;Arana 2013,pp. 289–290.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 328, 330–331;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 234;Lynch 2006,pp. 171–172;Arana 2013,p. 292.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 331;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 235;Arana 2013,pp. 295–296.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 331;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 235;Lynch 2006,p. 172;Langley 2009,pp. 81–82.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 331, 338–341;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 235–237;Lynch 2006,pp. 173–175;Langley 2009,p. 82;Arana 2013,pp. 295–305.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 394–395.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 343–345;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 240–241;Lynch 2006,pp. 175–176;Arana 2013,pp. 306–307.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 243;Arana 2013,pp. 305, 308.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 395–396.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 353;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 241;Lynch 2006,p. 183.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 354–356;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 242–243;Arana 2013,pp. 308–309.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 356;Lynch 2006,p. 184.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 243–244;Lynch 2006,p. 185;Langley 2009,p. 86;Arana 2013,pp. 310–311.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 243–244;Lynch 2006,p. 185;Langley 2009,pp. 86–87;Arana 2013,p. 312.

- ^abMcFarlane 2014,p. 398.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 362;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 244;Lynch 2006,pp. 185–186.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 364–366;Lynch 2006,pp. 186–187;Arana 2013,pp. 315, 317–318.

- ^Lynch 2006,pp. 189–190.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 368, 370;Lynch 2006,pp. 189–190.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 372–375;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 247–250;Lynch 2006,pp. 191–193;Langley 2009,p. 88;Arana 2013,pp. 320, 326–328.

- ^abMcFarlane 2014,p. 402.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 375;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 250.

- ^Masur 1969,p. 376;Arana 2013,p. 329.

- ^abMasur 1969,p. 376;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 251;Lynch 2006,p. 193;Arana 2013,p. 329.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 252;Lynch 2006,p. 193.

- ^Slatta & de Grummond 2003,p. 252;Arana 2013,p. 331.

- ^Masur 1969,pp. 378–379, 383;Slatta & de Grummond 2003,pp. 252–256;Lynch 2006,pp. 194–195;Arana 2013,pp. 331–335.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 402–405.

- ^McFarlane 2014,pp. 404–405.