Simurgh

Simurgh as the royal emblem of theSassanian Empire[1] | |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Persian mythology |

| Country | Ancient Iran |

Thesimurgh(/sɪˈmɜːrɡ/;Persian:سیمرغ,also spelledsenmurv, simorgh, simorg,simurg,simoorg, simorqorsimourv) is a benevolent bird inPersian mythologyandliterature.It bears some similarities withmythologicalbirds from different origins, such as thephoenix(Persian:ققنوسquqnūs) and thehumā(Persian:هما).[2]The figure can be found in all periods ofIranianart and literature and is also evident in the iconography ofGeorgia,[3]medieval Armenia,[4]theEastern Roman Empire,[5]and other regions that were within the realm of Persian cultural influence.

Etymology

[edit]ThePersianwordsīmurğ(سیمرغ) derives fromMiddle Persiansēnmurw[6][7](and earliersēnmuruγ), also attested inPazendtexts assīna-mrū.The Middle Persian word comes fromAvestanmərəγō Saēnō"the bird Saēna", originally a raptor, likely aneagle,falcon,orsparrowhawk,as can be deduced from the etymological cognateSanskritśyenaḥ(श्येनः) "raptor, eagle,bird of prey",which also appears as a divine figure.[8]Saēnais also a personal name. The word was lent to Armenian assiramarg(սիրամարգ) 'peacock'.[9]

On the other hand, the phrasesī murğ(سی مرغ) means "thirty birds" in Persian; this has been used byAttar of Nishapurin his symbolic story ofThe Conference of the Birds,theframe storyof which employs a play on the name.[10]

Mythology

[edit]

.

Form and function

[edit]The Simurgh is depicted inIranian artas a winged creature in the shape of a bird, gigantic enough to carry off an elephant or a whale. It appears as a peacock with the head of a dog and the claws of a lion – sometimes, however, also with a human face. The Simurgh is inherently benevolent.[12]Being part mammal, they suckle their young.[12][13]The Simurgh has an enmity towards snakes, and its natural habitat is a place with plenty of water.[12][13]Its feathers are said to be the colour of copper in some versions, and though it was originally described as being a dog-bird, later it was shown with either the head of a man or a dog.[12][13]

"Si-",the first element in the name, has been connected infolk etymologyto Modern Persiansi( "thirty" ). Although this prefix is not historically related to the origin of the namesimurgh,"thirty" has nonetheless been the basis for legends incorporating that number – for instance, that the simurgh was as large as thirty birds or had thirty colours (siræng). Other suggested etymologies include Pahlavisin murgh( "eagle bird" ) and Avestansaeno merego( "eagle" ).[12]

Iranian legends consider the bird so old that it had seen the destruction of the world three times over. The simurgh learned so much by living so long that it is thought to possess the knowledge of all the ages. In one legend, the simurgh was said to live 1,700 years before plunging itself into flames (much like thephoenix).[12]

The simurgh was considered to purify the land and waters and hence bestow fertility. The creature represented the union between the Earth and the sky, serving as mediator and messenger between the two. The simurgh roosted inGaokerena,theHōm(Avestan: Haoma) Tree of Life, which stands in the middle of the world sea (Vourukasha). The plant is potent medicine and is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. When the simurgh took flight, the leaves of the tree of life shook, making all the seeds of every plant fall out. These seeds floated around the world on the winds ofVayu-Vataand the rains ofTishtrya,in cosmology taking root to become every type of plant that ever lived and curing all the illnesses of mankind.

The relationship between the simurgh and Hōm is extremely close. Like the simurgh, Hōm is represented as a bird, a messenger, and the essence of purity that can heal any illness or wound. Hōm – appointed as the first priest – is the essence of divinity, a property it shares with the simurgh. The Hōm is in addition the vehicle offarr(ah)(MP:khwarrah,Avestan:khvarenah,kavaēm kharēno) ( "divine glory" or "fortune" ).Farrahin turn represents thedivine mandatethat was the foundation of a king's authority.

It appears as a bird resting on the head or shoulder of would-be kings and clerics, indicatingOrmuzd'sacceptance of that individual as his divine representative on Earth. For the commoner,Bahramwraps fortune/glory "around the house of the worshipper, for wealth in cattle, like the great bird Saena, and as the watery clouds cover the great mountains" (Yasht14.41, cf. the rains of Tishtrya above). Like the simurgh,farrahis also associated with the waters ofVourukasha(Yasht19.51, 56–57). In Yašt 12.17 Simorgh's (Saēna's) tree stands in the middle of the sea Vourukaša, it has good and potent medicine and is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it.

In theShahnameh

[edit]The simurgh made its most famous appearance inFerdowsi's epicShahnameh(Book of Kings), where its involvement with PrinceZalis described. According to theShahnameh,Zal,the son ofSaam,was born albino. When Saam saw his albino son, he assumed that the child was the spawn of devils, and abandoned the infant on the mountainAlborz.[14]

The child's cries were heard by the tender-hearted simurgh, who lived atop this peak, and she retrieved the child and raised him as her own. Zal was taught much wisdom from the loving simurgh, who has all knowledge, but the time came when he grew into a man and yearned to rejoin the world of men. Though the simurgh was terribly saddened, she gave him three golden feathers which he was to burn if he ever needed her assistance.[14]

Upon returning to his kingdom, Zal fell in love and married the beautifulRudaba.When it came time for their son to be born, the labor was prolonged and terrible; Zal was certain that his wife would die in labour. Rudaba was near death when Zal decided to summon the simurgh. The simurgh appeared and instructed him upon how to perform acesarean sectionthus saving Rudaba and the child, who became one of the greatest Persian heroes,Rostam.

Simurgh also shows up in the story of theSeven Trials of Esfandiyarin the latter's 5th labor. After killing the wicked enchantress,Esfandiyarfights a simurgh, and despite the simurgh's many powers, Esfandiyar strikes it in the neck,decapitatingit. The simurgh's offspring then rise to fight Esfandiyar, but they, too, are slain.[14]

In Persian Sufi poetry

[edit]

In classical and modern Persian literature the simorḡ is frequently mentioned, particularly as a metaphor for God inSufi mysticism.[7]In the 12th centuryConference of the Birds,Iranian Sufi poetFarid ud-Din Attarwrote of a band of pilgrim birds in search of the simurgh. In the poem, the birds of the world gather to decide who is to be their king, as they have none. Thehoopoe,the wisest of them all, suggests that they should find the legendary simorgh, a mythical Persian bird roughly equivalent to the westernphoenix.The hoopoe leads the birds, each of whom represent a human fault which prevents man from attaining enlightenment. When the group of thirty birds finally reach the dwelling place of the simorgh, all they find is a lake in which they see their own reflection. This scene employs a pun on the Persian expression for "thirty birds" (si morgh).[15]

The phrase also appears three times in Rumi'sMasnavi,e.g. in Book VI, Story IX: "The nest of thesī murğis beyondMount Qaf"(as translated by E.H. Whinfield).[16]

Through heavy Persian influence, the simurgh was introduced to theArabic-speaking world, where the concept was conflated with other Arabic mythical birds such as theghoghnus,a bird having some mythical relation with thedate palm,[17]and further developed as therukh(the origin of the English word "roc"). Representations of simurgh were adopted in earlyUmayyadart and coinage.[18]

In Kurdish folklore

[edit]Simurgh is shortened to "sīmir" in theKurdish language.[7]The scholarC. V. Treverquotes two Kurdish folktales about the bird.[7]These versions go back to the common stock of Iranian simorḡ stories.[7]In one of the folk tales, a hero rescues simurgh's offspring by killing a snake that was crawling up the tree to feed upon them. As a reward, the simurgh gives him three of her feathers which the hero can use to call for her help by burning them. Later, the hero uses the feathers, and the simurgh carries him to a distant land. In the other tale, the simurgh carries the hero out of the netherworld; here the simurgh feeds its young with its teats, a trait which agrees with the description of the simurgh in theMiddle Persianbook ofZadspram.In another tale, simurgh feeds the hero on the journey while the hero feeds simurgh with pieces of sheep's fat.

In popular culture

[edit]- Ambrose Bierce'sThe Devil's Dictionary(1906) characterizes the Simurgh as "omnipotent on condition that it do nothing" and likens it to the role of therabblein arepublic.[19]

- The title ofSalman Rushdie's first novel,Grimus(1975), is an anagram of Simurg.[20]

- Simurgh is the name of a proxy tool introduced in 2009 that helps residents of Iran avoidgovernment censorship of websites.[21]

- TheCrystal Simorghis an award given byFajr International Film Festival.

- The Simorgh is one of the creatures encountered by the protagonists in the 2006 movieAzur & Asmar: The Princes' Quest.

- The Simurgh is the name of one of the Endbringers in the 2011Worm (web serial).

- In the Yugioh card game, Simorgh is the Boss monster of its own archetype.

- A Simurgh card from a fictional collectible card game serves as a major plot device in the sci-fi novelEntanglement,by Gibson Monk.

- A simurgh appeared in chapter 49 of the mangaDelicious in Dungeonas Laois contemplates various bird-like monsters. It is shown large enough to hold an elephant in its talons.

- The Simurgh is featured in Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown, a 2024 video game in which it indirectly grants the player character various time-manipulation powers used to progress in the game.

- In her poem "Garden Simurgh",Kathleen Rainedescribes how 'I hung out nuts for the blue-tits but the sparrows came, / All thirty of them / With a flurry of wings, / One mind in thirty vociferous selves...' eventually concluding that no 'wonder-bird' should be deemed 'more miraculous' than these 'two-a-farthing sparrows / Each feather bearing the carelessly-worn signature / Of the universe'.[22]

Gallery

[edit]-

Simorgh on the reverse of an Iranian 500 rials coin

-

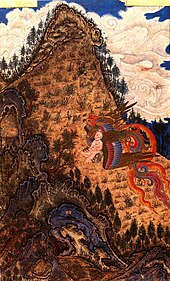

Simurgh at its nest

-

Decoration outside ofNadir Divan-Beghi madrasah,Bukhara

-

Painting of the Simurgh made in theMughal Empire

-

Imperial coat of arms prior to theRevolution,containing Simurgh icon

-

Simurgh platter. From Iran. Samanid dynasty, 9th–10th century CE. Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin

See also

[edit]- Anqa,Arabian mythological bird identified with the Simurgh

- Anzû(older reading: Zû), Mesopotamian monster

- Chamrosh,Persian mythological bird

- Chimera,Greek mythological hybrid monster

- Fenghuang,mythological bird of East Asia

- Garuda,Indian mythological bird

- Griffin or griffon,Greek lion-bird hybrid

- Huma bird,Iranian mythical bird

- Hybrid creatures in mythology

- Konrul,Turkish mythological hybrid bird

- Lamassu,Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- Luan,Chinese mythological bird related to the phoenix, whose name is often translated as "simurgh"

- Nue,Japanese legendary creature

- Oksoko,Slavic mythological double-headed eagle

- Pamola,A Legendary bird-spirit in Abenaki Mythology

- Pegasus,winged stallion in Greek mythology

- Pixiuor Pi Yao, Chinese mythical creature

- Roc,Arab and Persian legendary bird, the opposite of Anqa

- Shahbaz (bird),Persian mythological bird

- Simargl,a related being in Slavic mythology

- Sphinx,Greek mythical creature with lion's body and human head

- Turul,Turkic and Hungarian mythological bird of prey and a national symbol of Hungarians

- Ziz,giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

- Zhar Ptica,bird in Russian mythology parallel to thePhoenix

Notes

[edit]- ^Zhivkov, Boris (2015).Khazaria in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries.Brill. p. 78.ISBN978-9004294486.

- ^Juan Eduardo Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, p. 253

- ^For example, on the wall ofSamtavisi Cathedral

- ^For example, fresco depiction of simurghs inside medallions (evoking motifs found on Sassanid textiles) in the church of Tigran Honents atAni.P Donabedian and J. M. Thierry,Armenian Art,New York, 1979, p. 488.

- ^For example, a row of simurghs are depicted inside the "Ağaçaltı" church in theIhlaragorge. Thierry, N. and M.,Nouvelles églises rupestres de Cappadoce,Paris, 1963, pp. 84–85.

- ^A. Jeroussalimskaja, "Soieries sassanides", inSplendeur des sassanides: l'empire perse entre Rome et la Chine(Brussels, 1993) 114, 117–118, points out that the spellingsenmurv,is incorrect (noted by David Jacoby, "Silk Economics and Cross-Cultural Artistic Interaction: Byzantium, the Muslim World, and the Christian West",Dumbarton Oaks Papers58 (2004): 197–240, esp. 212 note 82.

- ^abcdeSchmidt, Hanns-Peter(2002)."Simorg".Encyclopedia Iranica.Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub.

- ^Mayrhofer, Manfred(1996). “śyená-”. In:Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen[Etymological Dictionary of Old Indo-Aryan] Volume II. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1996. p. 662. (In German)

- ^"Siramarg by Aram Sarkisian | Animators for Armenia | Animators for Armenia".BetterWorld.Retrieved23 July2024.

- ^"Al-Kindi Center for Research and Development (KCRD)".al-kindipublisher.Retrieved22 September2022.

- ^Compareti (University of California, Berkeley), Matteo (2015)."Ancient Iranian Decorative Textiles".The Silk Road.13:38.

- ^abcdefTÜFEKÇİ, ALİ (17 December 2020)."Journey in search of truth: Metaphorical story of Simurgh, sovereign of birds".Daily Sabah.Retrieved23 July2024.

- ^abcNair, Nitten (9 September 2022)."Simurgh: The Giant Bird".Mythlok.Retrieved23 July2024.

- ^abc"Flights of Imagination: How Birds Have Been Reinvented As Mythical Creatures Around The World — Object Lessons Space".objectlessons.space.Retrieved23 July2024.

- ^Hamid Dabashi (2012).The World of Persian Literary Humanism.Harvard University Press. p. 124.ISBN978-0674067592.

- ^Whinfield, E.H. (2001).Masnavi i Ma'navi(PDF).Ames, Iowa: Omphaloskepsis. p. 468.Retrieved25 September2022.

- ^Quranic articles; Vegetables in Holy Quran – The date-palm[dead link]

- ^Compareti, Matteo."The State of Research on Sasanian Painting".Humanities.uci.edu.Retrieved4 April2019.

- ^"Rabble" entry inThe Devil's DictionaryatDict.org

- ^"Salman Rushdie: Critical Essays Vol. 1".Atlantic Publishers.Page v

- ^"Trojan targets Iranian and Syrian dissidents via proxy tool".BBC News.30 May 2012.Retrieved21 December2020.

- ^Raine, Kathleen(2019).Collected Poems(2nd ed.). London: Faber & Faber Ltd. p. 340.ISBN978-0-571-35202-9.

References

[edit]- Ghahremani, Homa A. (1984)."Simorgh — An Old Persian Fairy Tale".Sunrise(June/July). Theosophical University Press.

External links

[edit] Media related toSimurghat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toSimurghat Wikimedia Commons