Soap

This articleis missing informationabout What determines hardness of soap and solubility to water and oil, why dissolving speed varies.(July 2024) |

Soapis asaltof afatty acidused in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products.[1]In a domestic setting, soaps aresurfactantsusually used forwashing,bathing,and other types ofhousekeeping.In industrial settings, soaps are used asthickeners,components of somelubricants,and precursors tocatalysts.

When used for cleaning, soapsolubilizesparticles and grime, which can then be separated from the article being cleaned. Inhand washing,as a surfactant, when lathered with a little water, soap killsmicroorganismsby disorganizing their membranelipid bilayeranddenaturingtheirproteins.[citation needed]It alsoemulsifiesoils, enabling them to be carried away by running water.[2]

Soap is created by mi xing fats and oils with abase.[3]Humans have used soap for millennia; evidence exists for the production of soap-like materials in ancientBabylonaround 2800 BC.

History

Ancient Middle East

It is uncertain as to who was the first to invent soap.[4]The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BC in ancientBabylon.[5]A formula for making soap was written on aSumerianclay tablet around 2500 BC; the soap was produced by heating a mixture of oil andwood ash,the earliest recorded chemical reaction, and used for washingwoolenclothing.[6]

TheEbers papyrus(Egypt, 1550 BC) indicates theancient Egyptiansused soap as a medicine and combined animal fats or vegetable oils with asoda ashsubstance calledtronato create their soaps.[6]Egyptian documents mention a similar substance was used in the preparation ofwoolfor weaving.[citation needed]

In the reign ofNabonidus(556–539 BC), a recipe for soap consisted ofuhulu[ashes],cypress[oil] and sesame [seed oil] "for washing the stones for the servant girls".[7]

In the SouthernLevant,the ashes frombarilla plants,such as species ofSalsola,saltwort (Seidlitzia rosmarinus) andAnabasis,were used in soap production, known aspotash.[8][9]Traditionally, olive oil was used instead of animal lard throughout the Levant, which was boiled in a copper cauldron for several days.[10]As the boiling progresses, alkali ashes and smaller quantities ofquicklimeare added and constantly stirred.[10]In the case of lard, it required constant stirring while kept lukewarm until it began to trace. Once it began to thicken, the brew was poured into a mold and left to cool and harden for two weeks. After hardening, it was cut into smaller cakes. Aromatic herbs were often added to the rendered soap to impart their fragrance, such asyarrowleaves,lavender,germander,etc.

Roman Empire

Pliny the Elder, whose writings chronicle life in the first century AD, describes soap as "an invention of the Gauls".[11] The wordsapo,Latin for soap, likely was borrowed from an early Germanic language and iscognatewith Latinsebum,"tallow".It first appears inPliny the Elder's account,[12]Historia Naturalis,which discusses the manufacture of soap from tallow and ashes. There he mentions its use in the treatment ofscrofulous sores,as well as among theGaulsas a dye to redden hair which the men inGermaniawere more likely to use than women.[13][14]The Romans avoided washing with harsh soaps before encountering the milder soaps used by the Gauls around 58 BC.[15]Aretaeus of Cappadocia,writing in the 2nd century AD, observes among "Celts, which are men called Gauls, those alkaline substances that are made into balls [...] calledsoap".[16]The Romans' preferred method of cleaning the body was to massage oil into the skin and then scrape away both the oil and any dirt with astrigil.[17]The standard design is a curved blade with a handle, all of which is made of metal.[18]

The 2nd-century AD physicianGalendescribes soap-making using lye and prescribes washing to carry away impurities from the body and clothes. The use of soap for personal cleanliness became increasingly common in this period. According to Galen, the best soaps were Germanic, and soaps from Gaul were second best.Zosimos of Panopolis,circa300 AD, describes soap and soapmaking.[19]

Ancient China

A detergent similar to soap was manufactured in ancient China from the seeds ofGleditsia sinensis.[20]Another traditional detergent is a mixture of pig pancreas and plant ash calledzhuyizi(simplified Chinese:Heo lá lách;traditional Chinese:Heo lá lách;pinyin:zhūyízǐ). Soap made of animal fat did not appear in China until the modern era.[21]Soap-like detergents were not as popular as ointments and creams.[20]

Islamic Golden Age

Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was produced in theMiddle Eastduring theIslamic Golden Age,when soap-making became an established industry. Recipes for soap-making are described byMuhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi(c. 865–925), who also gave a recipe for producingglycerinefromolive oil.In the Middle East, soap was produced from the interaction offatty oilsandfatswithalkali.InSyria,soap was produced using olive oil together with alkali andlime.Soap was exported from Syria to other parts of theMuslim worldand to Europe.[22]

A 12th-century document describes the process of soap production.[23]It mentions the key ingredient,alkali,which later became crucial to modern chemistry, derived fromal-qalyor "ashes".

By the 13th century, the manufacture of soap in the Middle East had become a major cottage industry, with sources inNablus,Fes,Damascus,andAleppo.[citation needed]

Medieval Europe

Soapmakers inNapleswere members of aguildin the late sixth century (then under the control of theEastern Roman Empire),[24]and in the eighth century, soap-making was well known in Italy and Spain.[25]TheCarolingiancapitularyDe Villis,dating to around 800, representing the royal will ofCharlemagne,mentions soap as being one of the products the stewards of royal estates are to tally. The lands ofMedieval Spainwere a leading soapmaker by 800, and soapmaking began in theKingdom of Englandabout 1200.[26]Soapmaking is mentioned both as "women's work" and as the produce of "good workmen" alongside other necessities, such as the produce of carpenters, blacksmiths, and bakers.[27]

In Europe, soap in the 9th century was produced from animal fats and had an unpleasant smell. This changed when olive oil began to be used in soap formulas instead, after which much of Europe's soap production moved to the Mediterranean olive-growing regions.[28]Hard toilet soap was introduced to Europe by Arabs and gradually spread as a luxury item. It was often perfumed.[22][28]By the 15th century, the manufacture of soap in theChristendomhad become virtually industrialized, with sources inAntwerp,Castile,Marseille,NaplesandVenice.[25]

16th–17th century

In France, by the second half of the 16th century, the semi-industrialized professional manufacture of soap was concentrated in a few centers ofProvence—Toulon,Hyères,andMarseille—which supplied the rest of France.[29]In Marseilles, by 1525, production was concentrated in at least two factories, and soap production at Marseille tended to eclipse the other Provençal centers.[30]English manufacture tended to concentrate in London.[31]

Finer soaps were later produced in Europe from the 17th century, using vegetable oils (such asolive oil) as opposed to animal fats. Many of these soaps are still produced, both industrially and by small-scale artisans.Castile soapis a popular example of the vegetable-only soaps derived from the oldest "white soap" of Italy. In 1634 Charles I granted the newly formed Society of Soapmakers a monopoly in soap production who produced certificates from 'foure Countesses, and five Viscountesses, and divers other Ladies and Gentlewomen of great credite and quality, besides common Laundresses and others', testifying that 'the New White Soap washeth whiter and sweeter than the Old Soap'.[32]

During theRestoration era(February 1665 – August 1714) a soap tax was introduced in England, which meant that until the mid-1800s, soap was a luxury, used regularly only by the well-to-do. The soap manufacturing process was closely supervised by revenue officials who made sure that soapmakers' equipment was kept under lock and key when not being supervised. Moreover, soap could not be produced by small makers because of a law that stipulated that soap boilers must manufacture a minimum quantity of one imperial ton at each boiling, which placed the process beyond the reach of the average person. The soap trade was boosted and deregulated when the tax was repealed in 1853.[33][34][35]

Modern period

Industrially manufacturedbar soapsbecame available in the late 18th century, as advertising campaigns in Europe and America promoted popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health.[36]In modern times, the use of soap has become commonplace in industrialized nations due to a better understanding of the role ofhygienein reducing the population size ofpathogenicmicroorganisms.[37]

-

Advertising for Dobbins' medicated toilet soap

-

A 1922 magazine advertisement forPalmolive Soap

-

Liquid soap

Until theIndustrial Revolution,soapmaking was conducted on a small scale and the product was rough. In 1780,James Keirestablished a chemical works atTipton,for the manufacture of alkali from the sulfates ofpotashand soda, to which he afterwards added a soap manufactory. The method of extraction proceeded on a discovery of Keir's. In 1790,Nicolas Leblancdiscovered how to make alkali fromcommon salt.[15]Andrew Pearsstarted making a high-quality, transparent soap,Pears soap,in 1807 in London.[38]His son-in-law,Thomas J. Barratt,became the brand manager (the first of its kind) for Pears in 1865.[39]In 1882, Barratt recruited English actress and socialiteLillie Langtryto become the poster-girl for Pears soap, making her the first celebrity to endorse a commercial product.[40][41]

William Gossageproduced low-priced, good-quality soap from the 1850s.Robert Spear Hudsonbegan manufacturing a soap powder in 1837, initially by grinding the soap with amortar and pestle.American manufacturerBenjamin T. Babbittintroduced marketing innovations that included the sale of bar soap and distribution ofproduct samples.William Hesketh Leverand his brother,James,bought a small soap works inWarringtonin 1886 and founded what is still one of the largest soap businesses, formerly called Lever Brothers and now calledUnilever.These soap businesses were among the first to employ large-scaleadvertisingcampaigns.

Liquid soap

This sectionis missing informationabout Chemical timeline: since when did the sulfonate surfactants appear? Was the original Palmolive soap in water?.(December 2020) |

Liquid soap was not invented until the nineteenth century; in 1865, William Sheppard patented a liquid version of soap.[42]In 1898, B.J. Johnson developed a soap derived from palm and olive oils; his company, theB.J. Johnson Soap Company,introduced "Palmolive"brand soap that same year.[43]This new brand of soap became popular rapidly, and to such a degree that B.J. Johnson Soap Company changed its name toPalmolive.[44]

In the early 1900s, other companies began to develop their own liquid soaps. Such products asPine-SolandTideappeared on the market, making the process of cleaning things other than skin, such as clothing, floors, and bathrooms, much easier.

Liquid soap also works better for more traditional or non-machine washing methods, such as using awashboard.[45]

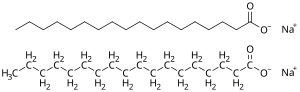

Types

Since they are salts of fatty acids, soaps have the general formula (RCO2−)nMn+,where R is analkyl,M is ametaland n is the charge of thecation.The major classification of soaps is determined by the identity of Mn+.When M isNa(sodium) orK(potassium), the soaps are calledtoilet soaps,used for handwashing. Many metaldications(Mg2+,Ca2+,and others) givemetallic soap.When M isLi,the result islithium soap(e.g.,lithium stearate), which is used in high-performancegreases.[46]A cation from anorganic basesuch asammoniumcan be used instead of a metal; ammoniumnonanoateis an ammonium-based soap that is used as an herbicide.[47]

When used inhard water,soap does not lather well and a scum ofstearate,a common ingredient in soap, forms as an insoluble precipitate.[48]

Non-toilet soaps

Soaps are key components of most lubricatinggreasesand thickeners. Greases are usuallyemulsionsofcalcium soapor lithium soap andmineral oil.Many other metallic soaps are also useful, including those ofaluminium,sodium,and mixtures thereof. Such soaps are also used as thickeners to increase theviscosityof oils. In ancient times, lubricating greases were made by the addition oflimetoolive oil.[49]

Metal soaps are also included in modern artists'oil paintsformulations as arheologymodifier.[50]

Production of metallic soaps

Most metal soaps are prepared by hydrolysis:

Toilet soaps

In a domestic setting, "soap" usually refers to what is technically called a toilet soap, used for household and personal cleaning.[51]When used for cleaning, soap solubilizes particles and fats/oils, which can then be separated from the article being cleaned. The insoluble oil/fat molecules become associated insidemicelles,tiny spheres formed from soap molecules with polarhydrophilic(water-attracting) groups on the outside and encasing alipophilic(fat-attracting) pocket, which shields the oil/fat molecules from the water making them soluble. Anything that is soluble will be washed away with the water.

Production of toilet soaps

The production of toilet soaps usually entailssaponificationoftriglycerides,which are vegetable or animal oils and fats. An alkaline solution (oftenlyeorsodium hydroxide) induces saponification whereby the triglyceride fats firsthydrolyzeinto salts of fatty acids.Glycerol(glycerin) is liberated. The glycerin can remain in the soap product as a softening agent, although it is sometimes separated.[52]

The type of alkali metal used determines the kind of soap product.Sodiumsoaps, prepared fromsodium hydroxide,are firm, whereaspotassiumsoaps, derived frompotassium hydroxide,are softer or often liquid. Historically, potassium hydroxide was extracted from the ashes ofbrackenor other plants. Lithium soaps also tend to be hard. These are used exclusively ingreases.

For making toilet soaps,triglycerides(oils and fats) are derived from coconut, olive, or palm oils, as well astallow.[53]Triglyceride is the chemical name for the triestersof fatty acids andglycerin.Tallow,i.e.,renderedfat, is the most available triglyceride from animals. Each species offers quite different fatty acid content, resulting in soaps of distinct feel. The seed oils give softer but milder soaps. Soap made from pureolive oil,sometimes calledCastile soaporMarseille soap,is reputed for its particular mildness. The term "Castile" is also sometimes applied to soaps from a mixture of oils with a high percentage of olive oil.

| Lauric acid | Myristic acid | Palmitic acid | Stearic acid | Oleic acid | Linoleic acid | Linolenic acid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fats | C12saturated | C14saturated | C16saturated | C18saturated | C18monounsaturated | C18diunsaturated | C18triunsaturated |

| Tallow | 0 | 4 | 28 | 23 | 35 | 2 | 1 |

| Coconut oil | 48 | 18 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Palm kernel oil | 46 | 16 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| Palm oil | 0 | 1 | 44 | 4 | 37 | 9 | 0 |

| Laurel oil | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 0 |

| Olive oil | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 78 | 10 | 0 |

| Canola oil | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 58 | 9 | 23 |

Soapmaking

A variety of methods are available for hobbyists to make soap.[54]Most soapmakers use processes where the glycerol remains in the product, and the saponification continues for many days after the soap is poured intomolds.The glycerol is left during the hot process method, but at the high temperature employed, the reaction is practically completed in the kettle, before the soap is poured into molds. This simple and quick process is employed in small factories all over the world.

Handmade soap from the cold process also differs from industrially made soap in that an excess of fat or (Coconut Oil, Cazumbal Process) are used, beyond that needed to consume thealkali(in a cold-pour process, this excess fat is called "superfatting" ), and the glycerol left in acts as a moisturizing agent. However, the glycerine also makes the soap softer. The addition of glycerol and processing of this soap producesglycerin soap.Superfatted soap is more skin-friendly than one without extra fat, although it can leave a "greasy" feel. Sometimes, anemollientis added, such asjojobaoil orshea butter.[55]Sandorpumicemay be added to produce ascouringsoap. The scouring agents serve to remove dead cells from the skin surface being cleaned. This process is calledexfoliation.

To makeantibacterialsoap, compounds such astriclosanortriclocarbancan be added. There is some concern that use of antibacterial soaps and other products might encourageantimicrobial resistancein microorganisms.[56]

Gallery

-

Dudu-Osun– a popular type ofAfrican black soap

-

Azul e branco soap– a bar of blue-white soap

-

TraditionalMarseille soap

-

Modern soap shop inTübingen(2019)

-

Lyebeing dissolved in water for soapmaking.

-

Greases for automotive applications contain soaps.

-

Soap on a platter

See also

Types of soap

- African black soap,popular in West Africa

- Aleppo soap,popular in Syria

- Castile soap,popular in Spain

- Marseille soap,popular in France

- Moroccan black soap,popular in Morocco

- Nabulsi soap,popular in the West Bank

- Saltwater soap,used to wash in seawater

- Shaving soap,used for shaving

- Vegan soap,made without use of animal byproducts

References

- ^IUPAC,Compendium of Chemical Terminology,2nd ed. (the "Gold Book" ) (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Soap".doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05721

- ^Tumosa, Charles S. (2001-09-01)."A Brief History of Aluminum Stearate as a Component of Paint".cool.conservation-us.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-18.Retrieved2017-04-05.

- ^"What's The Difference Between Soap and Detergent".cleancult.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-12-18.Retrieved2019-12-18.

- ^Derry, Thomas Kingston; Williams, Trevor Illtyd (1960-01-01).A Short History of Technology: From the Earliest Times to A. D. 1900.Courier Corporation. p. 265.ISBN9780486274720.

- ^Willcox, Michael (2000)."Soap".In Hilda Butler (ed.).Poucher's Perfumes, Cosmetics and Soaps(10th ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 453.ISBN978-0-7514-0479-1.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-08-20.

The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BCE in ancient Babylon.

- ^abVeerbek, H. (2012). "1 Historical Review". In Falbe, Jürgen (ed.).Surfactants in Consumer Products.Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–2.ISBN9783642715457– via Google Books.

- ^Noted inLevey, Martin (1958). "Gypsum, salt and soda in ancient Mesopotamian chemical technology".Isis.49(3): 336–342 (341).doi:10.1086/348678.JSTOR226942.S2CID143632451.

- ^Zohar Amar,Flora of the Bible,Jerusalem 2012, s.v.ברית,p. 216 (note 34)OCLC783455868.

- ^Abu-Rabiʻa, ʻAref (2001).Bedouin Century: Education and Development among the Negev Tribes in the Twentieth Century.New York. pp. 47–48.OCLC47119256.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-07-25.Retrieved2019-08-22.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^abCohen, Amnon (1989).Economic Life in Ottoman Jerusalem.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.p. 81.ISBN0521365511.

- ^"The history of soapmaking".The history of soapmaking.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-08-12.Retrieved2022-08-21.

- ^Harper, Douglas."Soap".etymonline.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-02-08.Retrieved2022-08-15.

- ^Pliny the Elder,Natural History,XXVIII.191.

- ^Martial,Epigrammata,VIII, 33, 20.Archived2013-01-21 at theWayback Machine

- ^abForeman, Amanda (October 4, 2019)."The Long Road to Cleanliness".wsj.Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2020.RetrievedOctober 6,2019.

- ^Aretaeus,The Extant Works of Aretaeus, the Cappadocian,ed. and tr. Francis Adams (London) 1856:238 and 496Archived2016-06-09 at theWayback Machine,noted in Michael W. Dols, "Leprosy in medieval Arabic medicine"Journal of the History of Medicine1979:316 note 9; the Gauls with whom the Cappadocian would have been familiar are those of AnatolianGalatia.

- ^De Puma, Richard. "A Third-Century B.C.E. Etruscan Tomb Group from Bolsena in the Metropolitan Museum of Art".American Journal of Archaeology:429–40.

- ^Padgett, J. Michael (2002).Objects of Desire: Greek Vases from the John B. Elliot Collection.Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University. pp. 36–48.

- ^Partington, James Riddick; Hall, Bert S (1999).A History of Greek Fire and Gun Powder.JHU Press. p.307.ISBN978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ^abJones, Geoffrey (2010)."Cleanliness and Civilization".Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-160961-9.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-07.

- ^Benn, Charles (2002).Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty.Oxford University Press. p. 116.ISBN978-0-19-517665-0.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-05.

- ^abAhmad Y. al-Hassan(2001),Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences,pages 73–74Archived2017-12-09 at theWayback Machine,UNESCO

- ^BBCScience and IslamPart 2, Jim Al-Khalili. BBC Productions. Accessed 30 January 2012.

- ^footnote 48, p. 104,Understanding the Middle Ages: the transformation of ideas and attitudes in the Medieval world,Harald Kleinschmidt, illustrated, revised, reprint edition, Boydell & Brewer, 2000,ISBN0-85115-770-X.

- ^abAnionic and Related Lime Soap Dispersants, Raymond G. Bistline Jr., inAnionic Surfactants: Organic Chemistry,Helmut Stache, ed., Volume 56 of Surfactant science series, CRC Press, 1996, chapter 11, p. 632,ISBN0-8247-9394-3.

- ^soap-flakesArchived2015-05-26 at theWayback Machine.soap-flakes. Retrieved on 2015-10-31.

- ^Robinson, James Harvey (1904).Readings in European History: Vol. I.Ginn and co.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-09-25.

- ^abCharles Springer, ed. (1954).A History of Technology, Volume 2.Clarendon Press. pp. 355–356.ISBN9780198581062.

- ^Nef, John U. (1936). "A Comparison of Industrial Growth in France and England from 1540 to 1640: III".The Journal of Political Economy.44(5): 643–666 (660ff.).doi:10.1086/254976.JSTOR1824135.S2CID222453265.

- ^Barthélemy, L. (1883) "La savonnerie marseillaise", noted by Nef 1936:660 note 99.

- ^Nef 1936:653, 660.

- ^Keith Thomas, 'Noisomeness,'London Review of Books,Vol. 42 No. 14, 16 July 2020

- ^"The Soap Tax".The Spectator Archive.The Spectator, London.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2017.Retrieved23 March2017.

- ^"Repeal of the Soap Tax".Parliamentary Debates (Hansard).3 April 1838.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2017.Retrieved23 March2013.

- ^Hansard, Thomas Curson (1864).Hansard's Parliamentary Debates.Uxbridge, England: Forgotten Books. pp. 363–374.ISBN9780243121328.

- ^McNeil, Ian (1990).An Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology.Taylor & Francis. pp. 2003–205.ISBN978-0-415-01306-2.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-05.

- ^Ahveninen, Anna (2020-03-31)."Hand sanitiser or soap: making an informed choice for COVID-19".Curious.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-05.Retrieved2020-08-04.

- ^Pears, Francis (1859).The Skin, Baths, Bathing, and Soap.The author. pp. 100–.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-04.

- ^Glenday, Craig (2013).Guinness World Records 2014.Guinness World Records Limited. pp.200.ISBN9781908843159.

- ^"When Celebrity Endorsers Go Bad".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on 16 November 2022.Retrieved2 March2022.

British actress Lillie Langtry became the world's first celebrity endorser when her likeness appeared on packages of Pears Soap.

- ^Richards, Jef I. (2022).A History of Advertising: The First 300,000 Years.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 286.

- ^US patent 49561,Sheppard, William, "Improved liquid soap", issued 1865-08-22

- ^Prigge, Matthew (2018-01-25)."The Story Behind This Bar of Palmolive Soap".Milwaukee Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-01-25.Retrieved2019-06-27.

- ^"Colgate-Palmolive Company History: Creating Bright Smiles for 200 Years".Colgate-PalmoliveCompany.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2006.Retrieved17 October2012.

- ^"The History of Liquid Soap".Blue Aspen Originals.Archivedfrom the original on 1 December 2012.Retrieved17 October2012.

- ^Klaus Schumann; Kurt Siekmann (2005). "Soaps".Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_247.ISBN978-3527306732.

- ^"Ammonium nonanoate (031802) Fact Sheet"(PDF).epa.gov.2006-09-21.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-11-16.Retrieved2022-08-15.

- ^Holman, John S.; Stone, Phil (2001).Chemistry.Nelson Thornes. p. 174.ISBN9780748762392.

- ^Thorsten Bartels; et al. (2005). "Lubricants and Lubrication".Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_423.ISBN978-3527306732.

- ^S., Tumosa, Charles (2001-09-01)."A Brief History of Aluminum Stearate as a Component of Paint".cool.conservation-us.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-18.Retrieved2017-03-17.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Kunatsa, Yvonne; Katerere, David R. (2021)."Checklist of African Soapy Saponin-Rich Plants for Possible Use in Communities' Response to Global Pandemics".Plants.10(5): 842.doi:10.3390/plants10050842.ISSN2223-7747.PMC8143558.PMID33922037.

Modern toilet soaps and detergents trace their origin to the ancient use of plants, commonly referred to as soapy plants, which possess foaming ability when they are agitated in water.

- ^Cavitch, Susan Miller.The Natural Soap Book.Storey Publishing, 1994ISBN0-88266-888-9.

- ^David J. Anneken, Sabine Both, Ralf Christoph, Georg Fieg, Udo Steinberner, Alfred Westfechtel "Fatty Acids" in Ullmann'sEncyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_245.pub2

- ^Garzena, Patrizia, and Tadiello, Marina (2013).The Natural Soapmaking Handbook.Online information and Table of ContentsArchived2015-07-30 at theWayback Machine.ISBN978-0-9874995-0-9/

- ^"The Process of Making Soap".edtech.mcc.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2019.Retrieved8 March2020.

- ^"Antibacterial Soaps Concern Experts".ABC News. 2006-01-06.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2014.Retrieved12 November2014.

Further reading

- Carpenter, William Lant; Leask, Henry (1895).A treatise on the manufacture of soap and candles, lubricants and glycerin.Free ebook atGoogle Books.

- Donkor, Peter (1986).Small-Scale Soapmaking: A Handbook.Ebook online atSlideShare.ISBN0-946688-37-0.

- Dunn, Kevin M. (2010).Scientific Soapmaking: The Chemistry of Cold Process.Clavicula Press.ISBN978-1-935652-09-0.

- Garzena, Patrizia, and Marina Tadiello (2004).Soap Naturally: Ingredients, methods and recipes for natural handmade soap.Online information and Table of Contents.ISBN978-0-9756764-0-0/

- Garzena, Patrizia, and Marina Tadiello (2013).The Natural Soapmaking Handbook.Online information and Table of Contents.ISBN978-0-9874995-0-9/

- Mohr, Merilyn (1979).The Art of Soap Making.A Harrowsmith Contemporary Primer. Firefly Books.ISBN978-0-920656-03-7.

- Spencer, Bob; Practical Action (2005).SOAPMAKINGArchived2020-09-21 at theWayback Machine.Ebook online.

- "Soap".Workshop Receipts, for Manufacturers and Scientific Amateurs.Vol. IVRain Water to Wire Ropes.London: E. & F. N. Spon. 1909. pp. 143–179.OCLC1159761115.

- Thomssen, E. G., Ph.D. (1922).Soap-Making Manual.Free ebook atProject Gutenberg.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 296–299.

- History of Soap making– SoapHistory