Sofia

Sofia

София | |

|---|---|

From the top to bottom-right, Panoramic view over central Sofia and theVitosha Mountain,Saint Alexander Nevsky Cathedral,Ivan Vazov National Theatre,Statue of Sveta Sofia,Sofia Central Mineral Baths | |

|

| |

| Motto(s): "Ever growing, never aging"[1] ( "Расте, но не старее" ) | |

| Coordinates:42°42′N23°20′E/ 42.70°N 23.33°E | |

| Country | Bulgaria |

| Province | Sofia City |

| Municipality | Capital |

| Cont. inhabited | since 7000 BC[2] |

| Neolithic settlement | 5500–6000 BC[3] |

| Thraciansettlement | 1400 BC[4][5] |

| Roman administration | 46 AD (asSerdica)[6] |

| Conquered byKrum | 809 AD (asSredets)[6] |

| Government | |

| •Mayor | Vasil Terziev(PP-DB-Spasi Sofia) |

| Area | |

| •Capital city | 500 km2(200 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 5,723 km2(2,210 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 10,738 km2(4,146 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 500–699 m (1,640–2,293 ft) |

| Population (2021)[10] | |

| •Capital city | 1,248,452 |

| • Density | 2,500/km2(6,500/sq mi) |

| •Urban | 1,547,779 |

| • Urban density | 270/km2(700/sq mi) |

| •Metro | 1,667,314 |

| • Metro density | 160/km2(400/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Sofian(en) Софиянец/Sofiyanets(bg) |

| Time zone | UTC+2(EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3(EEST) |

| Area code | (+359) 02 |

| HDI(2018) | 0.945[13] very high |

| Vehicle registration plate | C, CA, CB |

| Website | sofia |

Sofia(/ˈsoʊfiə,ˈsɒf-,soʊˈfiːə/SOH-fee-ə,SOF-;[14][15]Bulgarian:София,romanized:Sofiya,[16][17]IPA:[ˈsɔfijɐ]) is thecapitalandlargest cityofBulgaria.It is situated in theSofia Valleyat the foot of theVitoshamountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of theIskarriver and has many mineral springs, such as theSofia Central Mineral Baths.It has ahumid continental climate.Being in the centre of theBalkans,it is midway between theBlack Seaand theAdriatic Seaand closest to theAegean Sea.[18][19]

Known as Serdica inantiquityand Sredets in theMiddle Ages,Sofia has been an area ofhuman habitationsince at least 7000 BC. The recorded history of the city begins with the attestation of the conquest of Serdica by theRoman Republicin 29 BC from theCeltictribeSerdi.During the decline of theRoman Empire,the city was raided byHuns,Visigoths,Avars,andSlavs.In 809, Serdica was incorporated into theBulgarian EmpirebyKhanKrumand became known as Sredets. In 1018, theByzantinesended Bulgarian rule until 1194, when it was reincorporated by thereborn Bulgarian Empire.Sredets became a major administrative, economic, cultural and literary hub until its conquest by theOttomansin 1382. From 1530 to 1836, Sofia was the regional capital ofRumelia Eyalet,the Ottoman Empire's key province in Europe. Bulgarian rule was restored in 1878. Sofia was selected as the capital of theThird Bulgarian Statein the next year, ushering a period of intense demographic and economic growth.

Sofia is the14th-largest city in the European Union.It is surrounded by mountainsides, such asVitoshaby the southern side,Lyulinby the western side, and theBalkan Mountainsby the north, which makes it thethird highest European capitalafterAndorra la VellaandMadrid.Being Bulgaria's primary city, Sofia is home of many of the major local universities, cultural institutions and commercial companies.[20]The city has been described as the "triangle of religious tolerance". This is because three temples of three major world religions—Christianity,IslamandJudaism—are situated close together:Sveta Nedelya Church,Banya Bashi MosqueandSofia Synagogue.[21]This triangle was recently expanded to a "square" and includes the CatholicCathedral of St Joseph.[22]

Sofia has been named one of the top ten best places forstartup businessesin the world, especially in information technologies.[23]It was Europe's most affordable capital to visit in 2013.[24]TheBoyana Churchin Sofia, constructed during theSecond Bulgarian Empireand holding much patrimonial symbolism to theBulgarian Orthodox Church,was included onto theWorld Heritage Listin 1979. With its cultural significance inSoutheast Europe,Sofia is home to theNational Opera and Ballet of Bulgaria,theNational Palace of Culture,theVasil Levski National Stadium,theIvan Vazov National Theatre,theNational Archaeological Museum,and theSerdica Amphitheatre.TheMuseum of Socialist Artincludes many sculptures and posters that educate visitors about the lifestyle incommunist Bulgaria.[25]

The population of Sofia declined from 70,000 in the late 18th century, through 19,000 in 1870, to 11,649 in 1878, after which it began increasing.[26]Sofia hosts some 1.24 million[10]residents within a territory of 492 km2,[27]a concentration of 17.9% of the country population within the 200th percentile of the country territory. The urban area of Sofia hosts some 1.54 million[28]residents within 5723 km2,which comprisesSofia City Provinceand parts ofSofia Province(Dragoman,Slivnitsa,Kostinbrod,Bozhurishte,Svoge,Elin Pelin,Gorna Malina,Ihtiman,Kostenets) andPernik Province(Pernik,Radomir), representing 5.16% of the country territory.[7]The metropolitan area of Sofia is based upon one hour of car travel time, stretches internationally and includesDimitrovgradin Serbia.[29]The metropolitan region of Sofia is inhabited by a population of 1.66 million.[12]

Names[edit]

For a long time, the city possessed[30]aThracianname,Serdica(Ancient Greek:Σερδικη,Serdikē,orΣαρδικη,Sardikē;Latin:SerdicaorSardica), derived from the tribeSerdi,who were either ofThracian,[16][18]Celtic,[31]or mixed Thracian-Celtic origin.[32][33]The emperorMarcus Ulpius Traianus(53–117 AD) gave the city the combinative name ofUlpiaSerdica;[34][35]Ulpia may be derived from an Umbrian cognate of theLatinwordlupus,meaning "wolf"[36]or from the Latinvulpes(fox). It seems that the first written mention ofSerdicawas made during his reign and the last mention was in the 19th century in a Bulgarian text (Сардакіи,Sardaki). Other names given to Sofia, such asSerdonpolis(ByzantineGreek:Σερδών πόλις,"City of the Serdi" ) andTriaditza(Τριάδιτζα,"Trinity" ), were mentioned byByzantineGreeksources or coins. The Slavic nameSredets(Church Slavonic:Срѣдецъ), which is related to "middle" (среда,"sreda" ) and to the city's earliest name, first appeared on paper in an 11th-century text. The city was calledAtralisaby the Arab travellerIdrisiandStrelisa,Stralitsa,orStralitsionby theCrusaders.[37]

The nameSofiacomes from theSaint Sofia Church,[38]as opposed to the prevailingSlavicorigin of Bulgarian cities and towns.The origin is in the Greek wordsophía(σοφία,"wisdom" ). The earliest works where this latest name is registered are the duplicate of the Gospel of Serdica, in a dialogue between two salesmen fromDubrovnikaround 1359, in the 14th-century Vitosha Charter of Bulgarian tsarIvan Shishmanand in aRagusanmerchant's notes of 1376.[39]In these documents, the city is calledSofia,[clarification needed]but, at the same time, the region and the city's inhabitants are still calledSredecheski(Church Slavonic:срѣдечьскои,"of Sredets" ), which continued until the 20th century. TheOttomanscame to favour the nameSofya(صوفيه). In 1879, there was a dispute about what the name of the new Bulgarian capital should be, when the citizens created a committee of famous people, insisting for the Slavic name. Gradually, a compromise arose, officialisation ofSofiafor the nationwide institutions, while legitimating the titleSredetsfor the administrative and church institutions, before the latter was abandoned through the years.[40]

Geography[edit]

Sofia City Provincehas an area of 1344 km2,[41]while the surrounding and much biggerSofia Provinceis 7,059 km2.Sofia's development as a significant settlement owes much to its central position in theBalkans.It is situated in western Bulgaria, at the northern foot of theVitoshamountain, in theSofia Valleythat is surrounded by theBalkan mountainsto the north. The valley has an average altitude of 550 metres (1,800 ft). Sofia is the second highest capital of theEuropean Union(afterMadrid) and the third highest capital of Europe (afterAndorra la Vellaand Madrid). Unlike most European capitals, Sofia does not straddle any large river, but is surrounded by comparatively high mountains on all sides. Threemountain passeslead to the city, which have been key roads since antiquity, Vitosha being the watershed betweenBlackandAegean Seas.

A number of shallow rivers cross the city, including theBoyanska,VladayskaandPerlovska.TheIskar Riverin its upper course flows near eastern Sofia. It takes its source inRila,Bulgaria's highest mountain,[42]and enters Sofia Valley near the village ofGerman.The Iskar flows north toward the Balkan Mountains, passing between the eastern city suburbs, next to the main building and below the runways ofSofia Airport,and flows out of the Sofia Valley at the town ofNovi Iskar,where the scenicIskar Gorgebegins.[43]

The city is known for its 49mineralandthermalsprings. Artificial and dam lakes were built in the twentieth century.

While the 1818 and 1858 earthquakes were intense and destructive, the2012 Pernik earthquakeoccurred west of Sofia with amoment magnitudeof 5.6 and a much lower Mercalli intensity of VI (Strong). The2014 Aegean Sea earthquakewas also noticed in the city.

Climate[edit]

Sofia has ahumid continental climate(Köppen climate classificationDfb;Cfbif with −3 °Cisotherm) with an average annual temperature of 10.9 °C (51.6 °F).

Winters are relatively cold and snowy. In the coldest days temperatures can drop below −15 °C (5 °F), most notably in January. The lowest recorded temperature is −31.2 °C (−24 °F) (16 January 1893).[44][45]On average, Sofia receives a total snowfall of 98 cm (38.6 in) and 56 days with snow cover.[46]The snowiest recorded winter was 1939/1940 with a total snowfall of 169 cm (66.5 in).[47]The record snow depth is 57 cm (22.4 in) (25 December 2001).[48]The coldest recorded year was 1893 with an average January temperature of −10.4 °C (13 °F) and an annual temperature of 8.2 °C (46.8 °F).[49]

Summers are quite warm and sunny. In summer, the city generally remains slightly cooler than other parts of Bulgaria, due to its higher altitude. However, the city is also subject to heat waves with high temperatures reaching or exceeding 35 °C (95 °F) on the hottest days, particularly in July and August. The highest recorded temperature is 40.2 °C (104 °F) (5 July 2000).[50]The hottest recorded month was July 2012 with an average temperature of 24.8 °C (77 °F).[51]The warmest year on record was 2023 with an annual temperature of 12.1 °C (54 °F).[52]

Springs and autumns in Sofia are usually short with variable and dynamic weather.

The city receives an average precipitation of 625.7 mm (24.63 in) a year, reaching its peak in late spring and early summer whenthunderstormsare common. The driest recorded year was 2000 with a total precipitation of 304.6 mm (11.99 in), while the wettest year on record was 2014 with a total precipitation of 1,066.6 mm (41.99 in).[53][54]

| Climate data for Sofia (NIMH−BAS) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

22.2 (72.0) |

31 (88) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.1 (93.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39 (102) |

37.1 (98.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

4.6 (40.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15 (59) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

5.9 (42.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.2 (−24.2) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

−18 (0) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−2 (28) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−31.2 (−24.2) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 35.9 (1.41) |

35.5 (1.40) |

45.3 (1.78) |

52.3 (2.06) |

73.1 (2.88) |

81.6 (3.21) |

64.7 (2.55) |

53.1 (2.09) |

52.3 (2.06) |

53.9 (2.12) |

38.1 (1.50) |

39.9 (1.57) |

625.7 (24.63) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 24.9 (9.8) |

21 (8.3) |

15.4 (6.1) |

3 (1.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.5 (0.6) |

10.7 (4.2) |

21 (8.3) |

97.5 (38.5) |

| Average precipitation days | 10.7 | 9.4 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 13.9 | 12 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 118.2 |

| Average snowy days | 7.5 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 6.4 | 30.3 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 87.9 | 117.2 | 169 | 195.1 | 236 | 268.1 | 311.9 | 307.3 | 225.1 | 166.8 | 107.7 | 69.1 | 2,261.2 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source:NOAA/WMO,[55][56]StringMeteo,[57][58][59][60][61][62]Climatebase.ru[63]and Weather Atlas[64] | |||||||||||||

Environment[edit]

The geographic position of the Sofia Valley limits the flow of air masses, increasing the chances of air pollution by particulate matter andnitrogen oxide.[65]Solid fuel used for heating and motor vehicle traffic are significant sources of pollutants. Smog thus persists over the city astemperature inversionsand the mountains surrounding the city prevent the circulation of air masses.[66][67]As a result, air pollution levels in Sofia are some of the highest in Europe.[68]

Particulate matterconcentrations are consistently above the norm.[67]During the October 2017 – March 2018 heating season, particulate levels exceeded the norm on 70 occasions;[66]on 7 January 2018, PM10 levels reached 632 μg/m3,[69]some twelve times the EU norm of 50 μg/m3.[70]Even areas with few sources of air pollution, likeGorna Banya,had PM2.5 and PM10 levels above safe thresholds.[69]In response to hazardous spikes in air pollution, the Municipal Council implemented a variety of measures in January 2018, like more frequent washing of streets.[71]However, a report by theEuropean Court of Auditorsissued in September 2018 revealed that Sofia has not drafted any projects to reduce air pollution from heating. The report also noted that no industrial pollution monitoring stations operate in Sofia, even though industrial facilities are active in the city. A monitoring station on Eagles' Bridge, where some of the highest particulate matter values were measured, was moved away from the location and has measured sharply lower values since then.[72]Particulates are now largely measured by a network of 300 sensors maintained by volunteers since 2017.[66]TheEuropean Commissionhas taken Bulgaria to court over its failure to curb air pollution.[67]

History[edit]

This coin imitatesMacedonianissue from 187 to 168 BC. It was struck bySerditribe as their own currency.

Prehistory and antiquity[edit]

The area has a history of nearly 7,000 years,[73]with the great attraction of the hot water springs that still flow abundantly in the centre of the city. The neolithic village inSlatinadating to the 5th–6th millennium BC is documented.[74]Remains from another neolithic settlement around theNational Art Galleryare traced to the 3rd–4th millennium BC, which has been the traditional centre of the city ever since.[75]

The earliest tribes who settled were theThracianTilataei. In the 500s BC, the area became part of aThracianstate union, theOdrysian kingdomfrom another Thracian tribe theOdrysses.[76]

In 339 BCPhilip II of Macedondestroyed and ravaged the town for the first time.[77]

TheCeltictribeSerdigave their name to the city.[78]The earliest mention of the city comes from anAthenianinscription from the 1st century BC, attestingAstiu ton Serdon,i.e. city of theSerdi.[79]The inscription andDio Cassiustold that the Roman generalCrassussubdued theSerdiand behanded the captives.[80]

In 27–29 BC, according doDio Cassius,PlinyandPtolemy,the region "Segetike" was attacked byCrassus,which is assumed to be Serdica, or the city of the Serdi.[81][82][83]The ancient city is located betweenTZUM,Sheraton Hoteland the Presidency.[75][84]It gradually became the most important Roman city of the region.[34][35]It became amunicipiumduring the reign of EmperorTrajan(98–117). Serdica expanded, asturrets,protective walls,public baths,administrative and cult buildings, a civicbasilica,anamphitheatre,a circus, theCity council(Boulé), a large forum, a big circus (theatre), etc. were built. Serdica was a significant city on the Roman roadVia Militaris,connectingSingidunumandByzantium.In the 3rd century, it became the capital ofDacia Aureliana,[85]and when EmperorDiocletiandivided the province of Dacia Aureliana into Dacia Ripensis (at the banks of theDanube) andDacia Mediterranea,Serdica became the capital of the latter. Serdica's citizens ofThraciandescent were referred to asIllyrians[77]probably because it was at some time the capital ofEastern Illyria(Second Illyria).[86]

Roman emperorsAurelian(215–275)[87]andGalerius(260–311)[88]were born in Serdica.

The city expanded and became a significant political and economical centre, more so as it became one of the first Roman cities where Christianity was recognised as anofficial religion(underGalerius). TheEdict of Toleration by Galeriuswas issued in 311 in Serdica by the Roman emperor Galerius, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution of Christianity. The Edict implicitly granted Christianity the status of "religio licita",a worship recognised and accepted by the Roman Empire. It was the first edict legalising Christianity, preceding theEdict of Milanby two years.

Serdica was the capital of theDiocese of Dacia(337–602).

ForConstantine the Greatit was 'Sardica mea Roma est' (Serdica is my Rome). He considered making Serdica the capital of theByzantine Empireinstead of Constantinople.[89]which was already not dissimilar to atetrarchiccapital of the Roman Empire.[90]In 343 AD, theCouncil of Sardicawas held in the city, in a church located where the current 6th centuryChurch of Saint Sophiawas later built.

The city was destroyed in the447 invasionof theHunsand laid in ruins for a century[77]It was rebuilt byByzantine EmperorJustinian I.During the reign of Justinian it flourished, being surrounded with great fortress walls whose remnants can still be seen today.

Middle Ages[edit]

Serdica became part of theFirst Bulgarian Empireduring the reign of KhanKrumin 809, after a longsiege.The fall of the strategic city prompted a major and ultimately disastrous invasion of Bulgaria by theByzantineemperorNikephoros I,which led to his demise at the hands of theBulgarian army.[91]In the aftermath of the war, the city was permanently integrated in Bulgaria and became known by the Slavic name of Sredets. It grew into an important fortress and administrative centre under Krum's successor KhanOmurtag,who made it a centre of Sredets province (Sredetski komitat, Средецки комитат). The Bulgarian patron saintJohn of Rilawas buried in Sredets by orders of EmperorPeter Iin the mid 10th century.[92]After the conquest of the Bulgarian capitalPreslavbySviatoslav I of KyivandJohn I Tzimiskes' armies in 970–971, theBulgarian PatriarchDamyan chose Sredets for his seat in the next year and the capital of Bulgaria was temporarily moved there.[93]In the second half of 10th century the city was ruled byKomit Nikolaand his sons, known as the "Komitopuli".One of them wasSamuil,who was eventually crowned Emperor of Bulgaria in 997. In 986, the Byzantine EmperorBasil IIlaid siege to Sredets but after 20 days of fruitless assaults the garrison broke out and forced the Byzantines to abandon the campaign. On his way to Constantinople, Basil II was ambushed and soundly defeated by the Bulgarians in thebattle of the Gates of Trajan.[92][94]

The city eventually fell to theByzantine Empirein 1018, following theByzantine conquest of Bulgaria.Sredets joined theuprising of Peter Delyanin 1040–1041 in a failed attempt to restore Bulgarian independence and was the last stronghold of the rebels, led by the local commander Botko.[95]During the 11th century manyPechenegswere settled down in Sofia region as Byzantine federats.

It was once again incorporated into therestored Bulgarian Empirein 1194 at the time of EmperorIvan Asen Iand became a major administrative and cultural centre.[96]Several of the city's governors were members of the Bulgarian imperial family and held the title ofsebastokrator,the second highest at the time, after thetsar.Some known holders of the title wereKaloyan,Peterand their relative Aleksandar Asen (d. after 1232), a son ofIvan Asen I of Bulgaria(r. 1189–1196). In the 13th and 14th centuries Sredets was an important spiritual and literary hub with a cluster of 14 monasteries in its vicinity, that were eventually destroyed by the Ottomans. The city produced multicolored sgraffito ceramics, jewelry and ironware.[97]

In 1382/1383 or 1385, Sredets was seized by theOttoman Empirein the course of theBulgarian-Ottoman WarsbyLala Şahin Pasha,following athree-month siege.[98]The Ottoman commander left the following description of the city garrison: "Inside the fortress [Sofia] there is a large and elite army, its soldiers are heavily built, moustached and look war-hardened, but are used to consume wine andrakia—in a word, jolly fellows. "[99]

Early modern history[edit]

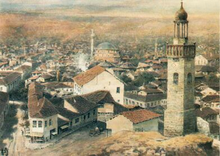

From the 14th century till the 19th century Sofia was an important administrative center in the Ottoman Empire. It became the capital of thebeylerbeylikofRumelia(Rumelia Eyalet), theprovincethat administered the Ottoman lands inEurope(theBalkans), one of the two together with the beylerbeylik ofAnatolia.It was the capital of the importantSanjak of Sofiaas well, including the whole ofThracewithPlovdivandEdirne,and part ofMacedoniawithThessalonikiandSkopje.[100]

During the initial stages of theCrusade of Varnain 1443, it was occupied by Hungarian forces for a short time in 1443, and the Bulgarian population celebrated a massSaint Sofia Church.Following the defeat of the crusader forces in 1444, the city's Christians faced persecution. In 1530 Sofia became the capital of theOttoman province(beylerbeylik) ofRumeliafor about three centuries. During that time Sofia was the largest import-export-base in modern-day Bulgaria for the caravan trade with theRepublic of Ragusa.In the 15th and 16th century, Sofia was expanded by Ottoman building activity. Public investments in infrastructure, education and local economy brought greater diversity to the city. Amongst others, the population consisted ofMuslims,BulgarianandGreekspeakingOrthodox Christians,Armenians,Georgians,CatholicRagusans, Jews (Romaniote,AshkenaziandSephardi), andRomani people.[98]The 16th century was marked by a wave of persecutions against the Bulgarian Christians, a total of nine becameNew Martyrsin Sofia and were sainted by the Orthodox Church, includingGeorge the New(1515), Sophronius of Sofia (1515), George the Newest (1530),Nicholas of Sofia(1555) and Terapontius of Sofia (1555).[101]

When it comes to the cityscape, 16th century sources mention eightFriday mosques,three public libraries, numerous schools, 12 churches, three synagogues, and the largestbedesten(market) of the Balkans.[98]Additionally, there were fountains andhammams(bathhouses). Most prominent churches such as Saint Sofia and Saint George were converted into mosques, and a number of new ones were constructed, includingBanya Bashi Mosquebuilt by the renowned Ottoman architectMimar Sinan.In total there were 11 big and over 100 small mosques by the 17th century.[102][103]In 1610 theVaticanestablished theSee of Sofiafor Catholics ofRumelia,which existed until 1715 when most Catholics had emigrated.[104]There was an important uprising against Ottoman rule in Sofia,Samokovand Western Bulgaria in 1737.

Sofia entered a period of economic and political decline in the 17th century, accelerated during the period of anarchy in the Ottoman Balkans of the late 18th and early 19th century, when local Ottoman warlords ravaged the countryside. 1831 Ottoman population statistics show that 42% of the Christians were non-taxpayers in thekazaof Sofia and the amount of middle-class and poor Christians were equal.[105]Since the 18th century thebeylerbeysof Rumelia often stayed inBitola,which became the official capital of the province in 1826. Sofia remained the seat of asanjak(district). By the 19th century the Bulgarian population had two schools and seven churches, contributing to theBulgarian National Revival.In 1858Nedelya Petkovacreated the first Bulgarian school for women in the city. In 1867 was inaugurated the firstchitalishtein Sofia – a Bulgarian cultural institution. In 1870 the Bulgarian revolutionaryVasil Levskiestablished arevolutionary committeein the city and in the neighbouring villages. Following his capture in 1873, Vasil Levski was transferred and hanged in Sofia by the Ottomans.

Modern and contemporary history[edit]

During theRusso-Turkish War of 1877–78,Suleiman Pashathreatened to burn the city in defence, but the foreign diplomats Leandre Legay,Vito Positano,Rabbi Gabriel Almosnino and Josef Valdhart refused to leave the city thus saving it. Many Bulgarian residents of Sofia armed themselves and sided with the Russian forces.[106]Sofia was relieved (seeBattle of Sofia) fromOttoman rulebyRussian forcesunder Gen.Iosif Gurkoon 4 January 1878. It was proposed as a capital byMarin Drinovand was accepted as such on 3 April 1879. By the time of its liberation the population of the city was 11,649.[107]

Most mosques in Sofia were destroyed in that war, seven of them destroyed in one night in December 1878 when a thunderstorm masked the noise of the explosions arranged by Russian military engineers.[108][109]Following the war, the great majority of the Muslim population left Sofia.[98]

For a few decades after the liberation, Sofia experienced large population growth, mainly by migration from other regions of the Principality (Kingdom since 1908) of Bulgaria, and from the still OttomanMacedoniaandThrace.

In 1900, the first electric lightbulb in the city was turned on.[110]

In theSecond Balkan War,Bulgaria was fighting alone practically all of its neighbouring countries. When theRomanian ArmyenteredVrazhdebnain 1913, then a village 11 kilometres (7 miles) from Sofia, now a suburb,[111]this prompted theTsardom of Bulgariato capitulate.[citation needed]During the war, Sofia was flown by theRomanian Air Corps,which engaged on photoreconnaissance operations and threw propaganda pamphlets to the city. Thus, Sofia became the first capital on the world to be overflown by enemy aircraft.[112]

During theSecond World War,Bulgaria declared war on the US and UK on 13 December 1941 and in late 1943 and early 1944 theUS and UK Air forces conducted bombings over Sofia.As a consequence of the bombings thousands of buildings were destroyed or damaged including the Capital Library and thousands of books. In 1944 Sofia and the rest of Bulgaria was occupied by the SovietRed Armyand within days of the Soviet invasion Bulgaria declared war on Nazi Germany.

In 1945, the communistFatherland Fronttook power. The transformations of Bulgaria into thePeople's Republic of Bulgariain 1946 and into the Republic of Bulgaria in 1990 marked significant changes in the city's appearance. The population of Sofia expanded rapidly due to migration from rural regions. New residential areas were built in the outskirts of the city, like Druzhba, Mladost and Lyulin.

During theCommunist Partyrule, a number of the city's most emblematic streets and squares were renamed for ideological reasons, with the original names restored after 1989.[113]

TheGeorgi Dimitrov Mausoleum,whereDimitrov'sbody had been preserved in a similar way to theLenin mausoleum,was demolished in 1999.

Cityscape[edit]

In Sofia there are 607,473 dwellings and 101,696 buildings. According to modern records, 39,551 dwellings were constructed until 1949, 119,943 between 1950 and 1969, 287,191 between 1970 and 1989, 57,916 in the 90s and 102,623 between 2000 and 2011. Until 1949, 13,114 buildings were constructed and between 10,000 and 20,000 in each following decade.[114]Sofia's architecture combines a wide range of architectural styles, some of which are aesthetically incompatible. These vary from Christian Roman architecture and medieval Bulgarian fortresses to Neoclassicism and prefabricated Socialist-era apartment blocks, as well as newer glass buildings and international architecture. A number of ancient Roman, Byzantine and medieval Bulgarian buildings are preserved in the centre of the city. These include the 4th centuryRotunda of St. George,the walls of the Serdica fortress and the partially preservedAmphitheatre of Serdica.

After the Liberation War, knyazAlexander Battenberginvited architects fromAustria-Hungaryto shape the new capital's architectural appearance.[115]

Among the architects invited to work in Bulgaria wereFriedrich Grünanger,Adolf Václav Kolář, andViktor Rumpelmayer,who designed the most important public buildings needed by the newly re-established Bulgarian government, as well as numerous houses for the country's elite.[115]Later, many foreign-educated Bulgarian architects also contributed. The architecture of Sofia's centre is thus a combination ofNeo-Baroque,Neo-Rococo,Neo-RenaissanceandNeoclassicism,with theVienna Secessionalso later playing an important part, but it is most typically Central European.

After World War II and the establishment of aCommunist governmentin Bulgaria in 1944, the architectural style was substantially altered.Stalinist Gothicpublic buildings emerged in the centre, notably the spacious government complex aroundThe Largo,Vasil Levski Stadium, the Cyril and Methodius National Library and others. As the city grew outwards, the then-new neighbourhoods were dominated by many concretetower blocks,prefabricated panel apartment buildings and examples ofBrutalist architecture.

After the abolition ofCommunismin 1989, Sofia witnessed the construction of whole business districts and neighbourhoods, as well as modern skyscraper-like glass-fronted office buildings, but also top-class residential neighbourhoods. The 126-metre (413 ft)Capital FortBusiness Centre is the first skyscraper in Bulgaria, with its 36 floors. However, the end of the old administration and centrally planned system also paved the way for chaotic and unrestrained construction, which continues today.

Green areas[edit]

The city has an extensivegreen belt.Some of the neighbourhoods constructed after 2000 are densely built up and lack green spaces. There are four principal parks –Borisova gradinain the city centre and theSouthern,WesternandNorthernparks. Several smaller parks, among which theVazrazhdane Park,Zaimov Park,City Gardenand theDoctors' Garden,are located in central Sofia. TheVitoshaNature Park (the oldestnational parkin theBalkans)[116]includes most ofVitoshamountain and covers an area of 266 square kilometres (103 sq mi),[117]with roughly half of it lying within the municipality of Sofia. Vitosha mountain is a popular hiking destination due to its proximity and ease of access via car and public transport. Two functioning cable cars provide year long access from the outskirts of the city. The mountain offers favourable skiing conditions during the winter. During the 1970s and the 1980s multiple ski slopes of varying difficulty were made available. Skiing equipment can be rented and skiing lessons are available. However, due to the bad communication between the private offshore company that runs the resort and Sofia municipality, most of the ski areas have been left to decay in the last 10 years, so that only one chairlift and one slope work.

Government and law[edit]

Local government[edit]

Sofia Municipalityis identical toSofia City Province,which is distinct fromSofia Province,which surrounds but does not include the capital itself. Besides the city proper, the 24 districts of Sofia Municipality encompass three other towns and 34 villages.[119]Districts and settlements have their own mayor who is elected in a popular election. The assembly members are chosen every four years. The common head of Sofia Municipality and all the 38 settlements is themayor of Sofia.[119]The mayorVasil Terzievis serving his first term, having won the2023 electionas the nominee of thePP-DBcoalition and the localSave Sofiaparty. After winning the first round of the election without receiving the majority of votes, Terziev entered a tight runoff againstBSPcandidateVanya Grigorova,which he won with 175,044 votes, compared to Grigorova’s 170,258.[120][121]

| # | District | km2 | Pop. | Density (/km2) | Extent | Mayor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sredets | 3 | 32,423 | 10,807 | City | RB |

| 2 | Krasno selo | 7 | 83,552 | 11,936 | City | RB |

| 3 | Vazrazhdane | 3 | 37,303 | 12,434 | City | GERB |

| 4 | Oborishte | 3 | 31,060 | 10,353 | City | RB |

| 5 | Serdika | 18 | 46,949 | 2,608 | City | GERB |

| 6 | Poduyane | 11 | 76,672 | 6,970 | City | GERB |

| 7 | Slatina | 13 | 66,702 | 5,130 | City | GERB |

| 8 | Izgrev | 5 | 30,896 | 6,179 | City | GERB |

| 9 | Lozenets | 9 | 53,080 | 5,897 | City | GERB |

| 10 | Triaditsa | 10 | 63,451 | 6,345 | City | GERB |

| 11 | Krasna polyana | 9 | 58,234 | 6,470 | City | GERB |

| 12 | Ilinden | 3 | 33,236 | 11,078 | City | GERB |

| 13 | Nadezhda | 19 | 67,905 | 3,573 | City | GERB |

| 14 | Iskar | 26 | 63,248 | 2,432 | City/satellites | GERB |

| 15 | Mladost | 17 | 102,899 | 6,052 | City | GERB |

| 16 | Studentski | 9 | 71,961 | 7,995 | City | GERB |

| 17 | Vitosha | 123 | 61,467 | 499 | City/satellites | RB |

| 18 | Ovcha kupel | 42 | 54,320 | 1,293 | City/satellites | GERB |

| 19 | Lyulin | 22 | 114,910 | 5,223 | City | GERB |

| 20 | Vrabnitsa | 44 | 47,969 | 1,090 | City/satellites | GERB |

| 21 | Novi Iskar | 220 | 28,991 | 131 | Satellites | GERB |

| 22 | Kremikovtsi | 256 | 23,641 | 92 | City/satellites | RB |

| 23 | Pancharevo | 407 | 28,586 | 70 | Satellites | GERB |

| 24 | Bankya | 53 | 12,136 | 228 | Satellites | GERB |

| TOTAL | 1342 | 1,291,591 | 962 | [1][122][123] |

National government[edit]

Sofia is the seat of the executive (Council of Ministers),legislative(National Assembly) andjudiciary(Supreme CourtandConstitutional Court) bodies of Bulgaria, as well as all government agencies, ministries, theNational Bank,and the delegation of theEuropean Commission.ThePresident,along with the Council of Ministers, is located onIndependence Square,also known as The Largo orThe Triangle of Power.[124]One of the three buildings in the architectural ensemble, the formerBulgarian Communist Partyheadquarters, is due to become the seat of the Parliament. A refurbishment project is due to be completed in mid-2019,[125]while theold National Assemblybuilding will become a museum or will only host ceremonial political events.[126]

Under Bulgaria's centralised political system, Sofia concentrates much of the political and financial resources of the country. It is the only city in Bulgaria to host three electoral constituencies: the23rd,24thand25th Multi-member Constituencies,which together field 42 mandates in the 240-member National Assembly.[127]

Crime[edit]

With a murder rate of 1.7/per 100.000 people (as of 2009[update]) Sofia is a relatively safe capital city.[128]Nevertheless, in the 21st century, crimes, includingBulgarian mafiakillings, caused problems in the city,[129]where authorities had difficulties convicting the actors,[130]which had caused theEuropean Commissionto warn the Bulgarian government that the country would not be able to join the EU unless it curbed crime[131](Bulgaria eventually joined in 2007).[132]Many of the most severe crimes arecontract killingsthat are connected toorganised crime,but these had dropped in recent years after several arrests of gang members.[133]Corruption in Bulgariaalso affects Sofia's authorities. According to the director of Sofia District Police Directorate, the largest share of the crimes are thefts, making up 62.4% of all crimes in the capital city. Increasing are frauds, drug-related crimes,petty theftandvandalism.[134]According to a survey, almost a third of Sofia's residents say that they never feel safe in the Bulgarian capital, while 20% always feel safe.[135]As of 2015[update],the consumer-reported perceived crime risk on theNumbeodatabase was "high" for theft and vandalism and "low" for violent crimes; safety while walking during daylight was rated "very high", and "moderate" during the night.[136]With 1,600 prisoners, theincarceration rateis above 0.1%;[137]however, roughly 70% of all prisoners are part of theRomani minority.[138]

Culture[edit]

Arts and entertainment[edit]

Sofia concentrates the majority of Bulgaria's leading performing arts troupes. Theatre is by far the most popular form of performing art, and theatrical venues are among the most visited, second only to cinemas. There were 3,162 theatric performances with 570,568 people attending in 2014.[139]TheIvan Vazov National Theatre,which performs mainly classical plays and is situated in the very centre of the city, is the most prominent theatre. TheNational Opera and Ballet of Bulgariais a combined opera and ballet collective established in 1891. Regular performances began in 1909. Some of Bulgaria's most famous operatic singers, such asNicolai GhiaurovandGhena Dimitrova,made their first appearances on the stage of the National Opera and Ballet.

Cinema is the most popular form of entertainment: there were more than 141,000 film shows with a total attendance exceeding 2,700,000 in 2014.[140]Over the past two decades, numerous independent cinemas have closed and most shows are in shopping centremultiplexes.Odeon(not part of theOdeon Cinemaschain) shows exclusively European and independent American films, as well as 20th century classics. The Boyana Film studios was at the centre of a once-thriving domestic film industry, which declined significantly after 1990.Nu Imageacquired the studios to upgrade them intoNu Boyana Film Studios,used to shoot scenes for a number of action movies likeThe Expendables 2,Rambo: Last BloodandLondon Has Fallen.[141][142]

Bulgaria's largest art museums are located in the central areas of the city. Since 2015, theNational Art Gallery,located in the formerroyal palace,theNational Gallery for Foreign Art(NGFA) and theMuseum of Contemporary Art – Sofia Arsenalwere merged to form theNational Gallery.Its largest branch is Kvadrat 500, located on the NFGA premises, where some 2,000 works are on display in twenty eight exhibition halls.[143]The collections encompass diverse cultural items, fromAshanti Empiresculptures andBuddhistart toDutch Golden Agepainting, works byAlbrecht Dürer,Jean-Baptiste GreuzeandAuguste Rodin.Thecryptof the Alexander Nevsky cathedral is another branch of the National Gallery. It holds a collection of Eastern Orthodox icons from the 9th to the 19th century.

TheNational History Museum,located inBoyana,it has a vast collection of more than 650,000 historical items dating from Prehistory to the modern era, although only 10,000 of them are permanently displayed due to the lack of space.[144]Smaller collections of historical items are displayed in theNational Archaeological Museum,a former mosque located between the edifices of the National Bank and the Presidency. Two natural sciences museums—theNatural History MuseumandEarth and Man—display minerals, animal species (alive andtaxidermic) and rare materials. The Ethnographic Museum and theMuseum of Military Historyhold large collections of Bulgarian folk costumes and armaments, respectively. ThePolytechnical Museumhas more than 1,000 technological items on display. TheSS. Cyril and Methodius National Library,the foremost information repository in the country, holds some 1,800,000 books and more than 7,000,000 documents, manuscripts, maps and other items.[145]

The city houses many cultural institutes such as the Russian Cultural Institute, thePolish Cultural Institute,the Hungarian Institute, the Czech and the Slovak Cultural Institutes, theItalian Cultural Institute,Confucius Institute,Institut Français,Goethe Institut,British CouncilandInstituto Cervanteswhich regularly organise temporary expositions of visual, sound and literary works by artists from their respective countries.

Some of the biggest telecommunications companies, TV and radio stations, newspapers, magazines, and web portals are based in Sofia, including theBulgarian National Television,bTVandNova TV.Top-circulation newspapers include24 ChasaandTrud.

TheBoyana Church,aUNESCOWorld Heritage site, contains realistic frescoes, depicting more than 240 human images and a total 89 scenes, were painted. With their vital, humanistic realism they are aRenaissancephenomenon at its culmination phase in the context of the common-European art.[146]

Tourism[edit]

Sofia is one of the most visited tourist destinations in Bulgaria alongside coastal and mountain resorts. Among its highlights is theAlexander Nevsky Cathedral,one of the symbols of Bulgaria, constructed in the late 19th century. It occupies an area of 3,170 square metres (34,122 square feet) and can hold 10,000 people.

The city center contains many remains of ancient Serdica that have been excavated and are on public display, includingComplex Ancient Serdica,eastern gate, western gate, city walls, thermal baths, 4th c.church of St. George Rotunda,amphitheatre of Serdica,the tombs and basilicas under thebasilica of St. Sophia.

Vitosha Boulevard,also calledVitoshka,is a pedestrian zone with numerous cafés, restaurants, fashion boutiques, andluxury goodsstores. Sofia'sgeographic location,in the foothills of the weekend retreatVitoshamountain, further adds to the city's specific atmosphere.

- Some of tourist attraction in Sofia

-

Vitosha Boulevard,the main shopping street in the city

Sports[edit]

A large number of sports clubs are based in the city. During the Communist era, most sports clubs concentrated on all-round sporting development, thereforeCSKA,Levski,Lokomotiv,andSlaviaare dominant not only in football, but in many other team sports as well. Basketball and volleyball also have strong traditions in Sofia. A notable localbasketballteam is twiceEuropean Champions CupfinalistLukoil Akademik.TheBulgarian Volleyball Federationis the world's second-oldest, and it was an exhibition tournament organised by the BVF in Sofia that convinced theInternational Olympic Committeeto include volleyball as anolympic sportin 1957.[147]Tennis is increasingly popular in the city. There are some ten[148]tennis courtcomplexes within the city including the one founded by formerWTAtop-five athleteMagdalena Maleeva.[149]

Sofia applied to host theWinter Olympic Gamesin 1992 and in 1994, coming second and third respectively. The city was also an applicant for the2014 Winter Olympics,but was not selected as candidate. In addition, Sofia hostedEuroBasket 1957and the1961and1977 Summer Universiades,as well as the1983and1989 winter editions.In 2012, it hosted theFIVB World Leaguefinals.

The city is home to a number of large sports venues, including the 43,000-seatVasil Levski National Stadiumwhich hosts international football matches, as well asBalgarska Armia Stadium,Georgi Asparuhov StadiumandLokomotiv Stadium,the main venues for outdoor musical concerts.Arena Sofiaholds many indoor events and has a capacity of up to 19,000 people depending on its use. The venue was inaugurated on 30 July 2011, and the first event it hosted was a friendly volleyball match between Bulgaria and Serbia. There are twoice skatingcomplexes — theWinter Sports Palacewith a capacity of 4,600 and the Slavia Winter Stadium with a capacity of 2,000, both containing two rinks each.[150]Avelodromewith 5,000 seats in the city'scentral parkis undergoing renovation.[151]There are also various other sports complexes in the city which belong to institutions other than football clubs, such as those of theNational Sports Academy,theBulgarian Academy of Sciences,or those of different universities. There are more than fifteen swimming complexes in the city, most of them outdoor.[152]Nearly all of these were constructed as competition venues and therefore have seating facilities for several hundred people.

There are twogolfcourses just to the east of Sofia — inElin Pelin(St Sofia club) and inIhtiman(Air Sofia club), and a horseriding club (St George club). Sofia was designated as European Capital of Sport in 2018. The decision was announced in November 2014 by the Evaluation Committee of ACES Europe, on the grounds that "the city is a good example of sport for all, as means to improve healthy lifestyle, integration and education, which are the basis of the initiative".

Demographics[edit]

Population over the years (in thousands):

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1887 | 30,501 | — |

| 1910 | 102,812 | +237.1% |

| 1934 | 287,095 | +179.2% |

| 1946 | 436,623 | +52.1% |

| 1956 | 644,727 | +47.7% |

| 1965 | 801,111 | +24.3% |

| 1975 | 967,214 | +20.7% |

| 1985 | 1,114,759 | +15.3% |

| 1992 | 1,114,925 | +0.0% |

| 2001 | 1,091,772 | −2.1% |

| 2011 | 1,202,761 | +10.2% |

| 2021 | 1,183,454 | −1.6% |

| Source: Censuses[153][154] | ||

According to 2018 data, the city has a population of 1,400,384 and the wholeSofia Capital Municipalityof 1,500,120.[155]The first census carried out in February 1878 by the Russian Army recorded a population of 11,694 inhabitants including 6,560Bulgarians,3,538Jews,839Turks,and 737Romani.

The ratio of women per 1,000 men was 1,102. Thebirth rateper 1000 people was 12.3 per mile and steadily increasing in the last 5 years, thedeath ratereaching 12.1 per mile and decreasing. The natural growth rate during 2009 was 0.2 per mile, the first positive growth rate in nearly 20 years. The considerable immigration to the capital from poorer regions of the country, as well as urbanisation, are among the other reasons for the increase in Sofia's population. Theinfant mortalityrate was 5.6 per 1,000, down from 18.9 in 1980. According to the 2011 census, people aged 20–24 years are the most numerous group, numbering 133,170 individuals and accounting for 11% of the total 1,202,761 people. The median age is 38 though. According to the census, 1,056,738 citizens (87.9%) are recorded as ethnicBulgarians,17,550 (1.5%) asRomani,6,149 (0.5%) asTurks,9,569 (0.8%) belonged to other ethnic groups, 6,993 (0.6%) do not self-identify and 105,762 (8.8%) remained with undeclared affiliation.[156][157]

According to the 2011 census, throughout the whole municipality some 892,511 people (69.1%) are recorded asEastern OrthodoxChristians, 10,256 (0.8%) asProtestant,6,767 (0.5%) asMuslim,5,572 (0.4%) asRoman Catholic,4,010 (0.3%) belonged to other faith and 372,475 (28.8%) declared themselvesirreligiousor did not mention any faith. The data says that roughly a third of the total population have already earned a university degree. Of the population aged 15–64 – 265,248 people within the municipality (28.5%) are not economically active, the unemployed being another group of 55,553 people (6%), a large share of whom have completed higher education. The largest group are occupied in trading, followed by those in themanufacturing industry.Within the municipality, three-quarters, or 965,328 people are recorded as having access to television at home and 836,435 (64.8%) as having internet. Out of 464,865 homes – 432,847 have connection to the communalsanitary sewer,while 2,732 do not have any. Of these 864 do not have anywater supplyand 688 have other than communal. Over 99.6% of males and females aged over 9 are recorded asliterate.The largest group of the population aged over 20 are recorded to live within marriage (46.3%), another 43.8% are recorded as single and another 9.9% as having other type of coexistence/partnership, whereas not married in total are a majority and among people aged up to 40 and over 70. The people with juridical status divorced orwidowedare either part of the factual singles or those having another type of partnership, each of the two constitutes by around 10% of the population aged over 20. Only over 1% of the juridically married do not de facto live within marriage. The families that consist of two people are 46.8%, another 34.2% of the families are made up by three people, whereas most of the households (36.5%) consist of only one person.[114]

Sofia was declared the national capital in 1879. One year later, in 1880, it was the fifth-largest city in the country afterPlovdiv,Varna,RuseandShumen.Plovdiv remained the most populous Bulgarian town until 1892 when Sofia took the lead. The city is the hot spot of internal migration, the capital population is increasing and is around 17% of the national,[158]thus a small number of people with local roots remain today, they dominate the surroundingrural suburbsand are calledShopi.Shopi speak theWestern Bulgarian dialects.

- Religious buildings in Sofia

Economy[edit]

Sofia is ranked as Beta-global cityby theGlobalization and World Cities Research Network.[159]It is the economic hub of Bulgaria and home to most major Bulgarian and international companies operating in the country, as well as theBulgarian National Bankand theBulgarian Stock Exchange.The city is ranked 62nd among financial centres worldwide.[160]In 2015, Sofia was ranked 30th out of 300 global cities in terms of combined growth in employment and real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, the highest one amongst cities in Southeast Europe.[161]The real GDP (PPP) per capita growth at the time was 2.5% and the employment went up by 3.4% to 962,400.[162]In 2015,Forbeslisted Sofia as one of the top 10 places in the world to launch astartup business,because of the low corporate tax (10%), the fast internet connection speeds available – one of the fastest in the world, and the presence of several investment funds, including Eleven Startup Accelerator, LAUNCHub and Neveq.[163]

The city's GDP (PPS) per capita stood at €29,600 ($33,760) in 2015, one of the highest in Southeast Europe and well above other cities in the country.[164]The total nominal GDP in 2018 was 38.5 billion leva ($22.4 billion), or 33,437 leva ($19,454) per capita,[165][166]and average monthly wages in March 2020 were $1,071, the highest nationally.[167]Services dominate the economy, accounting for 88.6% of thegross value added,followed by industry 11.3% and agriculture 0.1%.[165][168]

Historically, after World War II and the era of industrialisation under socialism, the city and its surrounding areas expanded rapidly and became the most heavily industrialised region of the country, with numerous factories producing steel, pig iron, machinery, industrial equipment, electronics, trams, chemicals, textiles, and food.[169]The influx of workers from other parts of the country became so intense that a restriction policy was imposed, and residing in the capital was only possible after obtaining Sofianite citizenship.[169]However, after the political changes in 1989, this kind of citizenship was removed.

The most dynamic sectors includeInformation technology(IT) and manufacturing. Sofia is a regional IT hub, ranking second among the Top 10 fastest growing tech centers in Europe in terms of annual growth of active members.[170]The sector employs about 50,000 professionals, 30% of them involved in programming, and contributes for 14% of the city's exports.[170]The IT sector is highly diverse and includes both multinational corporations, local companies and startups. Multinationals with major research, development, innovation and engineering centers in Sofia include the second largest global IT center ofCoca-Cola,[171]Ubisoft,[172]Hewlett-Packard,[173]VMware,[174]Robert Bosch GmbH,[175]Financial Times,[176]Experian,etc.[177]Several office and tech clusters have been established across the city, includingBusiness Park Sofia,Sofia Tech Park,Capital Fortand others.

Manufacturing has registered a strong recovery since 2012, increasing the exports three-fold and the employment by 52% accounting for over 70,000 jobs.[178]Supported by the city's R&D expertise, Sofia is shifting to high value-added manufacturing including electrical equipment, precision mechanics, pharmaceuticals. There are 16 industrial and logistics parks in Sofia, some sprawling to towns in neighbouringSofia Province,such asBozhurishte,KostinbrodandElin Pelin.[178]Manufacturing companies includeWoodward, Inc.,producing airframe and industrial turbomachinery systems,[179]Festo,producing microsensors,[180]Visteon,development and engineering of instrument clusters, LCD displays and domain controllers,[181]Melexis,producing micro-electronic semiconductor solutions in the automotive sector,[182]Sopharma, producing pharmaceuticals, the largestLufthansa Technikmaintenance facilities outside Germany etc.[183]

Transport and infrastructure[edit]

With its developing infrastructure and strategic location, Sofia is a major hub for international railway and automobile transport. Three of the tenPan-European Transport Corridorscross the city:IV,VIII,andX.[184]All major types of transport (exceptwater) are represented in the city.

TheCentral Railway Stationis the primary hub for domestic and international rail transport, carried out byBulgarian State Railways(BDZ), the national rail company headquartered in the city. It is one of the main stations alongBDZ Line 1,and a hub of Lines2,5,and13.Line 1 provides a connection toPlovdiv,the second-largest city in Bulgaria, while Line 2 is the longest national railway and connects Sofia andVarna,the largest coastal city. Lines 5 and 13 are shorter and provide connections toKulataandBankya,respectively. Overall, Sofia has 186 km (116 miles) of railway lines.[185]

Sofia Airporthandled 7,208,987 passengers in 2023.[186]

Public transportis well-developed withbus(2,380 km (1,479 mi)),[187]tram(308 km (191 mi)),[188]andtrolleybus(193 km (120 mi))[189]lines running in all areas of the city.[190][191]TheSofia Metrobecame operational in January 1998 with only 5 stations and currently has four lines and 47 stations.[192]As of 2022[update],the system has 52 km (32 mi) of track. Six new stations were opened in 2009, two more in April 2012, and eleven more in August 2012. In 2015 seven new stations were opened and the underground extended toSofia Airporton its Northern branch and toBusiness Park Sofiaon its Southern branch. In July 2016 theVitosha Metro Stationwas opened on the M2 main line. A third line was opened in August 2020 and re-organisation of the previous lines lead to a 4th line being created.[193]This line will complete the proposed underground system of three lines with about 65 km (40 mi) of lines.[194]The master plan for the Sofia Metro includes three lines with a total of 63 stations.[195]Until the late 2010s route taxis (marshrutka) provided an efficient and popularmeans of transportby being faster than public transport, but cheaper than taxis. Their use declined with the expansion of the metro and they were gradually phased out. There are around 13,000taxi cabsoperating in the city.[196]Additionally, all-electric vehiclesare available throughcarsharingcompanySpark,which is set to increase its fleet to 300 cars by mid-2019.[197]

Private automobile ownership has grown rapidly in the 1990s; more than 1,000,000 cars were registered in Sofia after 2002. The city has the 4th-highest number of automobiles per capita in the European Union at 546.4 vehicles per 1,000 people.[198]The municipality was known for minor and cosmetic repairs and many streets are in a poor condition. This is noticeably changing in the past years. There are different boulevards and streets in the city with a higher amount of traffic than others. These include Tsarigradsko shose, Cherni Vrah, Bulgaria, Slivnitsa, and Todor Aleksandrov boulevards, as well as the city's ring road.[199]Consequently, traffic and air pollution problems have become more severe and receive regular criticism in local media. The extension of the underground system is hoped to alleviate the city's immense traffic problems.

Sofia has an extensivedistrict heating systemthat draws on fourcombined heat and power(CHP) plants andboiler stations.Virtually the entire city (900,000 households and 5,900 companies) is centrally heated, using residual heat fromelectricity generation(3,000 MW) and gas- and oil-fired heating furnaces; totalheat capacityis 4,640 MW. The heat distribution piping network is 900 km (559 mi) long and comprises 14,000 substations and 10,000 heated buildings.

Education and science[edit]

Much of Bulgaria's educational capacity is concentrated in Sofia. There are 221 general, 11 special and seven arts or sports schools, 56 vocational gymnasiums and colleges, and four independent colleges.[200]The city also hosts 23 of Bulgaria's 51 higher education establishments and more than 105,000 university students.[201][202]TheAmerican College of Sofia,a private secondary school with roots in a school founded by American missionaries in 1860, is among the oldest American educational institutions outside of the United States.[203]

A number of secondary language schools provide education in a selected foreign language. These include theFirst English Language School,91st German Language School,164th Spanish Language School,and theLycée Français.These are among the most sought-after secondary schools, along withVladislav the Grammarian 73rd Secondary Schooland theHigh School of Mathematics,which topped the 2018 preference list for high school candidates.[204]

Higher education includes four of the five highest-ranking national universities –Sofia University(SU), theTechnical University of Sofia,New Bulgarian University,and theMedical University of Sofia.[205]Sofia University was founded in 1888.[206]More than 20,000 students[207]study in its 16 faculties.[208]A number of research and cultural departments operate within SU, including its own publishing house,botanical gardens,[209]a space research centre, aquantum electronicsdepartment,[210]and aConfucius Institute.[211]Rakovski Defence and Staff College,theNational Academy of Arts,theUniversity of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy,theUniversity of National and World Economy,and theUniversity of Mining and Geologyare other major higher education establishments in the city.[205]

Other institutions of national significance, such as theBulgarian Academy of Sciences(BAS) and theSS. Cyril and Methodius National Library,are located in Sofia. BAS is the centrepiece of scientific research in Bulgaria, employing more than 4,500 scientists in various institutes. Its Institute of Nuclear Research and Nuclear Energy will operate the largestcyclotronin the country.[212][213]All five of Bulgaria'ssupercomputersand supercomputing clusters are located in Sofia as well. Three of those are operated by the BAS; one bySofia Tech Parkand one by the Faculty of Physics at Sofia University.[214]

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Sofia istwinnedwith:

Cooperation agreements[edit]

In addition Sofia cooperates with:

Honour[edit]

Serdica PeakonLivingston Island,in theSouth Shetland Islands,Antarctica,is named after Serdica.

Mass Media[edit]

Public[edit]

- Bulgarian News Agency(1898)

- Bulgarian National Radio(1935)

- Bulgarian National Television(1959)

Private[edit]

- Nova Broadcasting Group(1994)

- bTV Media Group(2000)

See also[edit]

- List of churches in Sofia

- List of shopping malls in Sofia

- List of tallest buildings in Sofia

- Sofia Province

- Monument to the Tsar Liberator

References[edit]

- ^"Sofia through centuries".Sofia Municipality. Archived fromthe originalon 19 August 2009.Retrieved16 October2009.

- ^Ghodsee, Kristen (2005).The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism, and Postsocialism on the Black Sea.Duke UniversityPress. p.21.ISBN0822387174.

- ^Prehistory, Ivan Dikov · in (7 December 2015)."Archaeologist Discovers 8,000-Year-Old Nephrite 'Frog-like' Swastika in Slatina Neolithic Settlement in Bulgaria's Capital Sofia – Archaeology in Bulgaria".archaeologyinbulgaria.Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2015.Retrieved20 December2015.

- ^Marazov, Ivan (ed.). Ancient Gold: The Wealth of the Thracians. NY: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1998. Texts by Marazov, Ivan; Venedikov, Ivan; Fol, Alexander; Tacheva, Margarita.ISBN9780810919921.

- ^Popov, Dimitar (ed.). The Thracians, Iztok – Zapad, Sofia, 2011.ISBN9789543218691.

- ^abSofia 2016,p. 13.

- ^ab"CITIES AND THEIR URBANISED AREAS IN THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA"(PDF).National Statistical Institute:91.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 July 2018.Retrieved15 July2018.

- ^"Archived copy".Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2020.Retrieved25 August2020.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^"Nsi • National Register of Populated Places •".Archivedfrom the original on 11 July 2020.Retrieved8 July2020.

- ^ab"Население по градове и пол | Национален статистически институт".nsi.bg(in Bulgarian).Archivedfrom the original on 12 April 2021.Retrieved29 May2021.

- ^https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/urb_lpop1/default/table?lang=en.

{{cite web}}:Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ab"Eurostat – Data Explorer".appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on 3 December 2018.Retrieved21 December2016.

- ^"Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab".hdi.globaldatalab.org.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2018.Retrieved13 September2018.

- ^Wells, John C. (2008),Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.), Longman,ISBN9781405881180

- ^Roach, Peter (2011),Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary(18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN9780521152532

- ^ab"Sofia".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2018.Retrieved12 February2016.

- ^Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia.Britannica Educational Publishing. 1 June 2013.ISBN9781615309870.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2021.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^abLauwerys, Joseph (1970).Education in Cities.Evan's Brothers.ISBN0-415-39291-8.Archivedfrom the original on 11 July 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Rogers, Clifford (2010).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology.Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 301.ISBN9780195334036.Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2020.Retrieved27 June2019.

- ^Internet Hostel Sofia, Tourism in SofiaArchived28 December 2011 at theWayback Machine.Internethostelsofia.hostel, Retrieved Jan 2012

- ^"Triangle of Religious Tolerance (1903) – iCulturalDiplomacy".i-c-d.de.Archivedfrom the original on 27 January 2020.Retrieved27 December2019.

- ^"10 Things We Can all Learn from Bulgaria's Square of Religious Tolerance".15 February 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2020.Retrieved4 September2020.

- ^"Sofia is one of the top 10 places for start-up businesses in the world, Bulgarian National TV".Bnt.bg.Archived fromthe originalon 22 December 2015.Retrieved11 April2018.

- ^Clark, Jayne."Is Europe's most affordable capital worth the trip?".USA Today.Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2016.Retrieved12 February2016.

- ^"Museum of Socialist Art – National Gallery".Archived fromthe originalon 21 December 2019.Retrieved27 December2019.

- ^"История".kmeta.bg.10 May 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2018.Retrieved31 October2018.

- ^"NATIONAL STATISTICAL INSTITUTE – Information for the area of city of Sofia".Nsi.bg.Archivedfrom the original on 7 February 2018.Retrieved11 April2018.

- ^"Eurostat-Sofia urban area population".Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2015.Retrieved24 June2017.

- ^"Metropolitan areas in Europe"(PDF).Der Markt für Wohn- und Wirtschaftsimmobilien in Deutschland Ergebnisse des BBSR-Expertenpanel Immobilienmarkt Nr:95.ISSN1868-0097.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 15 July 2018.Retrieved15 July2018.

- ^Grant, Michael (211).The Emperor Constantine.Hachette.ISBN9781780222806.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^"The Cambridge Ancient History", Volume 3, Part 2:The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BCby John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond,ISBN0-521-22717-8,1992, p. 600: "In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long been supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin"

- ^Mihailov, G., Thracians, Sofia, 1972, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, quote in Bulgarian: Името серди е засвидетелствано след келтската инвазия на Балканите. Сердите са от смесен трако-келтски произход.

- ^Popov, D. Thracians, Sofia, p.h. Iztok – Zapad, 2005.

- ^abWorld and Its Peoples.Marshall Cavendish. 2010.ISBN9780761479024.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^abIrina Florov, Nicholas Florov (2001).Three-thousand-year-old Hat.Michigan University:Golden Vine Publishers. p. 303.ISBN0968848702.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2017.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Julian Bennett,Trajan: Optimus Princeps(Routledge, 1997), p. 1.

- ^Erwin Anton Gutkind (1964).International history of city development(8 ed.).Michigan University:Free Press of Glencoe.Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^"София"(in Bulgarian). Мила Родино. Archived fromthe originalon 19 December 2007.Retrieved14 September2008.

- ^Encyclopedia Americana(25 ed.).Pennsylvania State University:Grolier Incorporated. 1999. p. 878.ISBN0717201317.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2017.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^"History".Capital Municipality.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2015.Retrieved20 October2015.

- ^"District Sofia-city".Guide Bulgaria.Archivedfrom the original on 29 February 2012.Retrieved19 February2012.

- ^Geographic Dictionary of Bulgaria 1980,p. 537

- ^"General Hydrological Data".Iskar River System. Archived fromthe originalon 7 December 2017.Retrieved27 April2019.

- ^Софийска голяма община – климатArchived7 August 2020 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Ishirkov, Anastas (1910)."Атанас Иширков, България. Географически бележки, Придворна печатница, 1910 година, стр. 78".Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2020.Retrieved3 September2019.

- ^Николов, Иван."Архив-Бг3 » 01-1991 София".stringmeteo.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2021.Retrieved1 January2021.

- ^https:// stringmeteo /synop/sf_3747/1939-11.pdf[bare URL]

- ^Николов, Иван."Времето София » 25.12.2001".stringmeteo.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2015.Retrieved28 January2015.

- ^"Вековен архив - София » 01.1887 - 12.2007".stringmeteo.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2021.Retrieved17 May2021.

- ^"През 2000 година на 5 юли е бил един от".4 July 2023.

- ^"Времето-България » Мес. обобщ. температури".

- ^"Архив-Бг » Год. обобщ. температури".

- ^"Век. месечен архив Бг".Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2020.Retrieved18 January2020.

- ^"Архив-Бг » Год. обобщ. валежи".Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2020.Retrieved18 January2020.

- ^"Index of /Archive/Arc0216/0253808/2.2/Data/0-data/Region-6-WMO-Normals-9120/Bulgaria/CSV".

- ^https:// ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/normals/WMO/1961-1990/RA-VI/BU/15614.TXT[bare URL]

- ^"Век. месечен архив Бг".

- ^"Век. месечен архив Бг".

- ^https://view.officeapps.live /op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2F stringmeteo %2Fsynop%2Fclimate_bg%2FAbsolute_Maximum_Temperatures.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK[bare URL]

- ^https://view.officeapps.live /op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2F stringmeteo %2Fsynop%2Fclimate_bg%2FAbsolute_Minimum_Temperatures.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK[bare URL]

- ^https://web.uni-plovdiv.net/vedrin/sg/sg-bg-1947-1948.pdf

- ^"Времето София » 05.11.2021".

- ^"Browser Check Page".

- ^"Sofia, Bulgaria - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast".Archivedfrom the original on 9 March 2021.Retrieved3 September2019.

- ^""Дружба", "Надежда" и "Павлово" са с най-мръсен въздух в София – Mediapool.bg ".mediapool.bg.16 March 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved13 August2015.

- ^abc"Air pollution in Sofia, other Bulgarian cities hugely exceeded norms several times this winter".The Sofia Globe. 4 April 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2018.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^abcEnvironment: Sofia, most polluted capital of Europe(News report).Agence France-Presse.20 December 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 30 October 2021.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^Hakim, Danny (15 October 2013)."Bulgaria's Air Is Dirtiest in Europe, Study Finds, Followed by Poland".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2014.Retrieved15 October2013.

- ^ab"Bulgaria: Bad air quality in Sofia on January 6 2018".The Sofia Globe. 6 January 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 26 October 2018.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^"Air Quality Standards".European Commission.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2018.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^"Sofia Municipal Council Adopted Measures to Tackle Air Pollution".Bulgarian National Television.25 January 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2018.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^"Brussels: Sofia has no projects targeting air pollutionКопирано от fidget.bg".Standard.12 September 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 27 October 2018.Retrieved26 October2018.

- ^John G. Kelcey; Norbert Müller (7 June 2011).Plants and Habitats of European Cities.Czech Republic; Germany – University of Applied Sciences Erfurt:Springer.ISBN978-0-387-89684-7.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Boev, Zlatozar. (2009). Avian Remains from an Early Neolithic Settlement of Slatina (Present Sofia City, Bulgaria). Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. 61. 151–156.

- ^ab"София – 130 години столица на България".sofiaculture.bg.Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2017.

- ^BulWTours (20 July 2015)."Odrysian Kingdom - the first country on the Balkans".Bulgaria Wine Tours.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2022.Retrieved8 September2021.

- ^abcTrudy, Ring; Noelle, Watson; Paul, Schellinger (5 November 2013).Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places.Routledge.ISBN9781134259588.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020.Retrieved20 December2015.

- ^The Cambridge Ancient History,Volume 3, Part 2:,ISBN0-521-22717-8,1992, page 600

- ^"Емил Коцев 24.04.2016 9:331205 ИЗГУБЕНАТА СТОЛИЦА".Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2017.Retrieved12 October2018.

- ^"Dio, Roman History, Book 51, chapter 25".Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2014.Retrieved20 February2021.

- ^"Trakii︠a︡ – Том 12 – Страница 41-" Da diese mit ihrem blinden König Siras verbündete der Römer waren ergab dies den Vorwand für den Kriegszug von Crassus. Über die Segetike (wohl irrtümlich für Serdike, Land der Serden, wie es aus Dio Cass. LI, 25, 4 erhellt) "".1998.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2018.Retrieved12 October2018.

- ^"Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Akademai Klado, 1966." Als sie die Dentheleten angriffen, kam Crassus diesen zur. Hilfe, eroberte das Land der Serden (bei Dio Segetika) und kam plündernd ins. "".1966.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2018.Retrieved12 October2018.

- ^Jenő Fitz. Limes. Akadémiai Kiadó, 1977 "As Macedonia itself was in danger, Crassus readily advanced as far as Segetika (-Serdica)"Archived12 October 2018 at theWayback Machine,ISBN9789630513012

- ^Ivanov, Rumen (2006).Roman cities in Bulgaria.Bulgarian Bestseller--National Museum of Bulgarian Books and Polygraphy.ISBN9789544630171.Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Wilkes, John (2005). "Provinces and Frontiers". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (eds.).The Cambridge ancient history: The crisis of empire, A.D. 193–337.Vol. 12. Cambridge University Press. p. 253.ISBN978-0-521-30199-2.Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2015.Retrieved29 October2015.

- ^Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal dictionary of arts, sciences, and literature.University of Minnesota. 1827.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Saunders, Randall Titus (1992).A biography of the Emperor Aurelian (AD 270–275).Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Dissertation Services. pp. 106–7.

- ^"Eutropius: Book IX".thelatinlibrary.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.Retrieved16 February2012.

- ^Nikolova, KapkaSofiaArchived20 August 2020 at theWayback MachineUniversity of Indiana. "Emperor Constantine the Great even considered the possibility for Serdika to become the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire"

- ^Green, Bernard (2010).Christianity in Ancient Rome: The First Three Centuries.A&C Black. p. 237.ISBN978-0-567-03250-8.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2020.Retrieved12 September2017.

- ^Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999,pp. 127–128

- ^abStancheva 2010,pp. 120–121

- ^Slaviani.1967.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved27 June2019.

- ^Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999,p. 319

- ^Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999,pp. 400–401

- ^Stancheva 2010,pp. 123–124

- ^Stancheva 2010,pp. 131, 139

- ^abcdIvanova, Svetlana, "Ṣofya", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 23 January 2018.

- ^Cited in Халенбаков, О.Детска енциклопедия България: Залезът на царете,с. 18

- ^Godisnjak.Drustvo Istoricara Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo. 1950. p. 174.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved27 June2019.

Санџак Софија Овај је санџак основан око г. 1393.

- ^Stancheva 2010,pp. 165, 167–169

- ^Stancheva 2010,pp. 154–155

- ^"Sofia – Trip around Sofia".Balkan tourist, 1968. Archived fromthe originalon 5 March 2016.Retrieved8 August2015.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913)."Sardica".Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913)."Sardica".Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^Kemal Karpat(1985),Ottoman Population, 1830-1914, Demographic and Social CharacteristicsArchived10 October 2019 at theWayback Machine,The University of Wisconsin Press,p. 36

- ^"ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Генов Ц. Русско-турецкая война 1877–1878 гг. и подвиг освободителей".lib.ru.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2016.Retrieved8 August2015.

- ^Kiradzhiev, Svetlin (2006). "Sofia. 125 years a capital. 1879–2004". "Guttenberg".ISBN978-954-617-011-8

- ^Crampton 2006,p. 114.

- ^Crampton, RJ (2006) [1997],A Concise History of Bulgaria,Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,ISBN0-521-85085-1

- ^"E-novinar – Новините на едно място"[Mohailova, Tihomria. In 1900 the first electric lamp lit the streets of Sofia. Novinar].novinar.bg(in Bulgarian). 12 March 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 18 June 2016.Retrieved22 December2016.

- ^Hall (2000), p. 97.

- ^Hall (2000), p. 118.

- ^L. Ivanov.1991 Sofia street naming proposal.Archived25 October 2017 at theWayback MachineSofia City Place-names Commission, 22 January 1991.

- ^ab2011 census, Sofia-capital(PDF)(23 ed.). Sofia:National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.2012. p. 37 40 43 68 71 74 99 117 132 190 193 196. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 15 February 2016.

- ^abCollective (1980).Encyclopedia of Figurative Arts in Bulgaria, volume 1.Sofia:Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.pp. 209–210.

- ^"National parks in the world"(in Bulgarian). journey.bg.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2008.Retrieved24 May2008.

- ^"Vitosha Mountain".vitoshamount.hit.bg. Archived fromthe originalon 20 June 2004.Retrieved29 April2014.

- ^"Sofia Council - Общински съветници 2023-2027".council.sofia.bg.Retrieved2 July2024.

- ^ab"District Mayors".Sofia Municipality. Archived fromthe originalon 20 December 2009.Retrieved26 December2009.

- ^https://results.cik.bg/mi2023/tur1/rezultati/2246.html

- ^https://results.cik.bg/mi2023/tur2/rezultati/2246.html

- ^"Sofia BG - Столична община"(PDF).5 November 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 November 2011.

- ^"Местни избори:: Местни избори и национален референдум 2015".Cik.bg.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2016.Retrieved11 April2018.

- ^""Триъгълникът на властта" или Ларгото: Как се е променял през годините "[The Triangle of Power or The Largo: How It Changed Throughout the Years]. Bulgarian National Television.Archivedfrom the original on 6 June 2020.Retrieved1 November2018.

- ^"Как ще изглежда новата пленарна зала на българските депутати?"[What will the new Parliament hall look like?]. Bulgarian National Television. 2 October 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2021.Retrieved1 November2018.

- ^"Народното събрание – музей?"[The National Assembly – a Museum?]. BTV Novinite. 7 October 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2018.Retrieved1 November2018.

- ^"РЕШЕНИЕ № 4149-НС София, 27.01.2017"[Resolution No. 4149-NS Sofia]. Central Electoral Commission. 27 January 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2019.Retrieved1 November2018.