Spolia

Spolia(Latinfor 'spoils';sg.:spolium) are stones taken from an old structure and repurposed for new construction or decorative purposes. It is the result of an ancient and widespread practice (spoliation) whereby stone that has been quarried, cut and used in a built structure is carried away to be used elsewhere. The practice is of particular interest to historians, archaeologists and architectural historians since the gravestones, monuments and architectural fragments of antiquity are frequently found embedded in structures built centuries or millennia later. The archaeologistPhilip A. Barkergives the example of a late Roman period (probably 1st-century) tombstone fromWroxeterthat could be seen to have been cut down and undergone weathering while it was in use as part of an exterior wall and, possibly as late as the 5th century, reinscribed for reuse as a tombstone.[1]

Overview

[edit]

The practice of spoliation was common inlate antiquity.Entire structures, including underground foundations, are known to have been demolished to enable the construction of new ones. According to Baxter, two churches in Worcester (one 7th century and one 10th) are thought to have been deconstructed so that their building stone could be repurposed bySt. Wulstanto construct a cathedral in 1084.[1]And the parish churches ofAtcham,Wroxeter,andUpton Magnaare largely built of stone taken from the buildings ofViroconium Cornoviorum.[1]

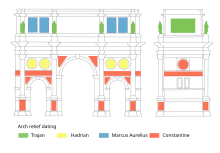

Roman examples include theArch of Janus,the earlier imperial reliefs reused on theArch of Constantine,the colonnade ofOld Saint Peter's Basilica;examples in Byzantine territories include the exterior sculpture on thePanagia Gorgoepikooschurch inAthens); in the medieval West Roman tiles were reused inSt Albans Cathedral,in much of the medieval architecture ofColchester,porphyry columns in thePalatine Chapel in Aachen,and the colonnade of the basilica ofSanta Maria in Trastevere.Spoliain the medieval Islamic world include the columns in thehypostylemosques ofKairouan,GazaandCordoba.Although the modern literature onspoliais primarily concerned with these and other medieval examples, the practice is common and there is probably no period of art history in which evidence for "spoliation" could not be found.

Interpretations ofspoliagenerally alternate between the "ideological" and the "pragmatic". Ideological readings might describe the re-use of art and architectural elements from former empires or dynasties as triumphant (that is, literally as the display of "spoils" or "booty" of the conquered) or as revivalist (proclaiming the renovation of past imperial glories). Pragmatic readings emphasize the utility of re-used materials: if there is a good supply of old marble columns available, for example, there is no need to produce new ones. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive, and there is certainly no one approach that can account for all instances of spoliation, as each instance must be evaluated within its particular historical context.

Spoliahadapotropaicspiritual value. Clive Foss has noted[2]that in the 5th century crosses were inscribed on the stones of pagan buildings, as atAnkara,where crosses were inscribed on the walls of theTemple of Augustus and Rome.Foss suggests that the purpose of this was to ward off thedaimonesthat lurked in stones that had been consecrated to pagan usage. Liz James extends Foss's observation[3]in noting that statues, laid on their sides and facing outwards, were carefully incorporated in Ankara's city walls in the 7th century, at a time whenspoliawere also being built into city walls inMiletus,Sardis,EphesusandPergamum:"laying a statue on its side places it and the power it represents under control. It is a way of acquiring the power of rival gods for one's own benefit", James observes. "Inscribing a cross works similarly, sealing the object for Christian purposes".[4]

There has been considerable controversy over the use of Jewish gravestones as pavement materials in several Eastern European countries during and afterThe Holocaust,[5][6][7]as well as by Jordan duringtheir rule over East Jerusalem.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Fragments of Greek inscriptions in the masonry of the OttomanHeptapyrgion(Yedikule) fortress (1431),Thessaloniki,Greece

-

Spoliain the city wall ofİznik,Turkey, at Lefke Gate

-

Ionic ordercolumn incorporated into a wall,Bosra,Syria

-

SpoliaatRavenna Baptistery of Neon,Ravenna,Italy

-

18th-century illustration of a Roman statue and inscriptions reused in the walls of theCittadella,Gozo,Malta. The statue has since been removed and it is now in theGozo Museum of Archaeology.

-

Romanspoliain the foundation ofChurch of St. DonatusinZadar,Croatia

-

Jewish headstones used as part of a wall inLviv,Ukraine

-

Portrait of the Four Tetrarchsin the corner ofSt Mark's Basilica,inVenice,Italy, looted by Venetians fromConstantinopleduring theFourth Crusade

-

Spoliafrom thePatras Castle

See also

[edit]- Crisis of the 3rd Century

- Roman Empire#Tetrarchy (285–324) and Constantine the Great (324–337)

- Dominate

- Palimpsest– the practice of erasing old texts from scarce oldvellumto write new text

- Diocletian's Palace– a Roman Imperial palace in Split, re-purposed by later inhabitants as a town

- Slighting

- Spolia opima– armour and arms a Roman general stripped from the body of an opposing commander slain in single combat

References

[edit]- ^abcBarker, A. Philip (1977).Techniques of Archaeological Excavation.Routledge. p. 11.

- ^Foss, "Late Antique and Byzantine Ankara"Dumbarton Oaks Papers31(1977:65).

- ^James, "'Pray Not to Fall into Temptation and Be on Your Guard': Pagan Statues in Christian Constantinople"Gesta35.1 (1996:12–20) p. 16.

- ^James 1996, noting O. Hjort, "Augustus Christianus—Livia Christiana:Sphragisand Roman portrait sculpture ", in L. Ryden and J.O. Rosenqvist,Aspects of Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium(Transactions of the Swedish Institute in Istanbul, IV) 1993:93–112.

- ^Musleah, Rahel (1995-11-26)."U.S. Prods to Reclaim Holocaust Cemeteries".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved2023-07-05.

- ^Hahn, Avital Louria (1997-09-14)."Restoring a Jewish Cemetery in Poland".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved2023-07-05.

- ^Lipman, Steve (2003-05-16)."Saving Cemeteries Here And Abroad".Jewish Week.Archived fromthe originalon 2022-01-28.Retrieved2023-07-05.

- ^Balfour, Alan (2019).The Walls of Jerusalem: Preserving the Past, Controlling the Future.John Wiley & Sons. p. 162.ISBN978-1-119-18229-0.

Further reading

[edit]There is a large modern literature on spolia, and the following list makes no claim to be comprehensive.

- J. Alchermes, "Spolia in Roman Cities of the Late Empire: Legislative Rationales and Architectural Reuse,"Dumbarton Oaks Papers48 (1994), 167–78.

- S. Bassett,The urban image of late antique Constantinople(Cambridge, 2004).

- L. Bosman,The power of tradition: Spolia in the architecture of St. Peter's in the Vatican(Hilversum, 2004).

- B. Brenk, "Spolia from Constantine to Charlemagne: Aesthetics versus Ideology,"Dumbarton Oaks Papers41 (1987), 103–09.

- B. Brenk, "Sugers Spolien,"Arte Medievale1 (1983), 101–107.

- R. Brilliant, "I piedistalli delgiardino di Boboli:spolia in se, spolia in re, "Prospettiva31 (1982), 2–17.

- C. Bruzelius,"Columpnas marmoreas et lapides antiquarum ecclesiarum: The Use of Spolia in the Churches ofCharles II of Anjou,"inArte d'Occidente: temi e metodi. Studi in onore di Angiola Maria Romanini(Rome, 1999), 187–95.

- F.W. Deichmann,Die Spolien in der spätantike Architektur(Munich, 1975).

- J. Elsner, "From the Culture of Spolia to the Cult of Relics: The Arch of Constantine and the Genesis of Late Antique Forms,"Papers of the British School at Rome68 (2000), 149–84.

- A. Esch, "Spolien: Zum Wiederverwendung antike Baustücke und Skulpturen in mittelalterlichen Italien,"Archiv für Kunstgeschichte51 (1969), 2–64.

- F.B. Flood, "The Medieval Trophy as an Art Historical Trope: Coptic and Byzantine 'Altars' in Islamic Contexts,"Muqarnas18 (2001).

- J.M. Frey,Spolia in Fortifications and the Common Builder in Late Antiquity(Leiden, 2016)

- M. Greenhalgh,The Survival of Roman Antiquities in the Middle Ages(London, 1989). (Available online,provided by author)

- M. Greenhalgh, "Spolia in fortifications: Turkey, Syria and North Africa," inIdeologie e pratiche del reimpiego nell'alto medioevo(Settimane di Studi del Centro Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo 46), (Spoleto, 1999). (Available online,provided by author)

- M. Fabricius Hansen,The eloquence of appropriation: prolegomena to an understanding of spolia in early Christian Rome(Rome, 2003).

- B. Kiilerich, "Making Sense of the Spolia in the Little Metropolis in Athens," 'Arte medievale n.s. anno IV, 2, 2005, 95–114.

- B. Kiilerich, "Antiquus et modernus: Spolia in Medieval Art - Western, Byzantine and Islamic", in Medioevo: il tempo degli antichi, ed. A.C. Quintavalle, Milan 2006,135-145.

- D. Kinney, "Spolia from the Baths of Caracalla in Sta. Maria in Trastevere,"Art Bulletin68 (1986), 379–97.

- D. Kinney, "Rape or Restitution of the Past? Interpreting Spolia," in S.C. Scott, ed.,The Art of Interpreting(University Park, 1995), 52–67.

- D. Kinney, "Making Mute Stones Speak: Reading Columns inS. Nicola in CarcereandS. Maria Antiqua,"in C.L. Striker, ed.,Architectural Studies in Memory ofRichard Krautheimer(Mainz, 1996), 83–86.

- D. Kinney, "Spolia. Damnatio and renovatio memoriae,"Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome42 (1997), 117–148.

- D. Kinney, "Roman Architectural Spolia,"Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society145 (2001), 138–161.

- D. Kinney, "Spolia," in W. Tronzo, ed.,St. Peter's in the Vatican(Cambridge, 2005), 16–47.

- D. Kinney, "The concept of Spolia," in C. Rudolph, ed.,A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe(Oxford, 2006), 233–52.

- L. de Lachenal,Spolia: uso e rempiego dell'antico dal III al XIV secolo(Milan, 1995).

- P. Liverani, "Reimpiego senza ideologia: la lettura antica degli spolia dall’arco di Costantino all’età carolingia,"Römische Mitteilungen111 (2004), 383–434.

- J. Lomax, "Spoliaas Property, "Res Publica Litterarum20 (1997), 83–94.

- S. Lorenzatti,Vicende del Tempio di venere e Roma nel medioevo e nel Rinascimento,in "Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e storia dell’Arte",13. 1990, pp. 119–138.

- C. Mango, "Ancient Spolia in the Great Palace of Constantinople," inByzantine East, Latin West. Art Historical Studies in Honor of Kurt Weitzmann(Princeton, 1995), 645–57.

- H.-R. Meier, "Vom Siegeszeichen zum Lüftungsschacht: Spolien als Erinnerungsträger in der Architektur," in: Hans-Rudolf Meier und Marion Wohlleben (eds.),Bauten und Orte als Träger von Erinnerung: Die Erinnerungsdebatte und die Denkmalpflege(Zürich: Institut für Denkmalpflege der ETH Zürich, 2000), 87–98. (pdf)

- M. Muehlbauer, "From Stone to Dust: The Life of the Kufic Inscribed Frieze of Wuqro Cherqos in Tigray, Ethiopia,"Muqarnas38 (2021), 1-34.PDF

- R. Müller,Spolien und Trophäen im mittelalterlichen Genua: sic hostes Ianua frangit(Weimar, 2002).

- J. Poeschke and H. Brandenburg, eds.,Antike Spolien in der Architektur des Mittelalters und der Renaissance(Munich, 1996).

- H. Saradi, "The Use of Spolia in Byzantine Monuments: the Archaeological and Literary Evidence,"International Journal of the Classical Tradition3 (1997), 395–423.

- Annette Schäfer,Spolien: Untersuchungen zur Übertragung von Bauteilen und ihr politischer Symbolgehalt am Beispiel von St-Denis, Aachen und Magdeburg(M.A. thesis, Bamberg, 1999).

- S. Settis, “Continuità, distanza, conoscenza: tre usi dell’antico,” in S. Settis, ed.,Memoria dell’antico nell’arte italiana(Torino, 1985), III.373–486.

- B. Ward-Perkins,From Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages: Urban Public Building in Northern and Central Italy A.D. 300–850(Oxford, 1984)