Stegoceras

| Stegoceras Temporal range:Late Cretaceous,

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two reconstructedS. validumskeletons based on specimen UALVP 2,Royal Tyrrell Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Pachycephalosauria |

| Family: | †Pachycephalosauridae |

| Genus: | †Stegoceras Lambe,1902 |

| Type species | |

| †Stegoceras validum Lambe, 1902

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Stegocerasis agenusofpachycephalosaurid(dome-headed)dinosaurthat lived in what is nowNorth Americaduring theLate Cretaceousperiod,about 77.5 to 74 million years ago (mya). The first specimens fromAlberta,Canada, were described in 1902, and thetype speciesStegoceras validumwas based on these remains. The generic name means "horn roof", and the specific name means "strong". Several other species have been placed in the genus over the years, but these have since been moved to other genera or deemedjunior synonyms.Currently onlyS. validumandS. novomexicanum,named in 2011 from fossils found inNew Mexico,remain. The validity of the latter species has also been debated, and it may not even belong to the genusStegoceras.

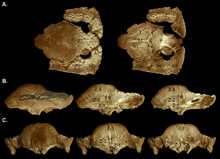

Stegoceraswas a small,bipedaldinosaur about 2 to 2.5 metres (6.6 to 8.2 ft) long, and weighed around 10 to 40 kilograms (22 to 88 lb). The skull was roughly triangular with a short snout, and had a thick, broad, and relatively smooth dome on the top. The back of the skull had a thick "shelf" over theocciput,and it had a thick ridge over the eyes. Much of the skull was ornamented bytubercles(or round "outgrowths" ) and nodes (or "knobs" ), many in rows, and the largest formed small horns on the shelf. The teeth were small and serrated. The skull is thought to have been flat in juvenile animals and to have grown into a dome with age. It had a rigidvertebral column,and a stiffened tail. The pelvic region was broad, perhaps due to an extended gut.

Originally known only from skull domes,Stegoceraswas one of the first known pachycephalosaurs, and the incompleteness of these initial remains led to many theories about the affinities of this group. A completeStegocerasskull with associated parts of the skeleton was described in 1924, which shed more light on these animals. Pachycephalosaurs are today grouped with the hornedceratopsiansin the groupMarginocephalia.Stegocerasitself has been consideredbasal(or "primitive" ) compared to other pachycephalosaurs.Stegoceraswas most likely herbivorous, and it probably had a good sense of smell. The function of the dome has been debated, and competing theories include use inintra-specific combat(head or flank-butting),sexual display,orspecies recognition.S. validumis known from theDinosaur Park Formationand theOldman Formation,whereas the controversialS. novomexicanumis known from theFruitlandandKirtland Formation.

History of discovery

[edit]

The first known remains ofStegoceraswere collected by CanadianpalaeontologistLawrence Lambefrom theBelly River Group,in theRed Deer Riverdistrict of Alberta,Canada.These remains consisted of two partial skull domes (specimens CMN 515 and CMN 1423 in theCanadian Museum of Nature) from two animals of different sizes collected in 1898, and a third partial dome (CMN 1594) collected in 1901. Based on these specimens, Lambe described and named the newmonotypicgenus and speciesStegoceras validusin1902.[1][2]The generic nameStegocerascomes from theGreekstegè/στέγη, meaning "roof" andkeras/κέρας meaning "horn". The specific namevalidusmeans "strong" in Latin, possibly in reference to the thick skull-roof.[3]Because the species was based on multiple specimens (asyntype series), CMN 515 was designated as thelectotype specimenbyJohn Bell Hatcherin 1907.[4][2]

As no similar remains had been found in the area before, Lambe was unsure of what kind of dinosaur they were, and whether they represented one species or more; he suggested the domes were "prenasals" situated before thenasal boneson the midline of the head, and noted their similarity to the nasal horn-core of aTriceratopsspecimen.[1]In 1903, Hungarian palaeontologistFranz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvássuggested that the fragmentary domes ofStegoceraswere in fact frontal and nasal bones, and that the animal would therefore have had a single, unpaired horn. Lambe was sympathetic to this idea of a new type of "unicorn dinosaur" in a 1903 review of Nopscsa's paper. At this time, there was still uncertainty over which group of dinosaurStegocerasbelonged to, with bothceratopsians(horned dinosaurs) andstegosaurs(plated dinosaurs) as contenders.[5][6]Hatcher doubted whether theStegocerasspecimens belonged to the same species and whether they were dinosaurs at all, and suggested the domes consisted of the frontal, occipital, and parietal bones of the skull.[2]In 1918, Lambe referred another dome (CMN 138) toS. validus,and named a new species,S. brevis,based on specimen CMN 1423 (which he originally included inS. validus). By this time, he considered these animals as members of Stegosauria (then composed of both families of armoured dinosaurs,StegosauridaeandAnkylosauridae), in a new family he called Psalisauridae (named for the vaulted or dome-shaped skull roof).[7]

In 1924, the American palaeontologistCharles W. Gilmoredescribed a complete skull ofS. validuswith associated postcranial remains, by then the most complete remains of a dome-headed dinosaur. It was discovered in the Belly River Group by the American palaeontologistGeorge F. Sternbergin 1926, and catalogued as specimen UALVP 2 in theUniversity of AlbertaLaboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology. This find confirmed Hatcher's interpretation of the domes as consisting of the frontoparietal area of the skull. UALVP 2 was found with small, disarticulated bony elements, then thought to begastralia(abdominal ribs), which are not known in otherornithischiandinosaurs (one of the two main groups of dinosaurs). Gilmore pointed out that the teeth ofS. validuswere very similar to those of the speciesTroodon formosus(named in 1856 and by then only known from isolated teeth), and described a skull dome discovered close to the locality whereTroodonwas found. Therefore, Gilmore consideredStegocerasan invalidjunior synonymofTroodon,thereby renamingS. validusintoT. validus,and suggested that even the two species might be the same. Furthermore, he foundS. brevisto be identical toS. validus,and therefore a junior synonym of the latter. He also placed these species in the new familyTroodontidae(since Lambe had not selected a type genus for his Psalisauridae), which he considered closest to theornithopoddinosaurs.[8][9]Because the skull seemed so specialized compared to the rather "primitive" -looking skeleton, Nopcsa doubted whether these parts actually belonged together, and suggested the skull belonged to anodosaur,the skeleton to an ornithopod, and the supposed gastralia (belly ribs) to a fish. This claim was rebutted by Gilmore and Loris S. Russell in the 1930s.[10]

Gilmore's classification was supported by the American palaeontologistsBarnum BrownandErich Maren Schlaikjerin their 1943 review of the dome-headed dinosaurs, by then known from 46 skulls. From these specimens, Brown and Schlaikjer named the new speciesT. sternbergiandT. edmontonensis(both from Alberta), as well as moving the large speciesT. wyomingensis(which was named in 1931) to the new genusPachycephalosaurus,along with two other species. They foundT. validusdistinct fromT. formosus,but consideredS. brevisthe female form ofT. validus,and therefore a junior synonym. By this time, the dome-headed dinosaurs were either considered relatives of ornithopods or of ankylosaurs.[10]In 1945, after examining casts ofT. formosusandS. validusteeth, the American palaeontologistCharles M. Sternbergdemonstrated differences between the two, and instead suggested thatTroodonwas atheropoddinosaur, and that the dome-headed dinosaurs should be placed in their own family. ThoughStegoceraswas the first member of this family to be named, Sternberg named the groupPachycephalosauridaeafter the second genus, as he found that name (meaning "thick head lizard" ) more descriptive. He also consideredT. sternbergiandT. edmontonensismembers ofStegoceras,foundS. brevisvalid, and named a new species,S. lambei,based on a specimen formerly referred toS. validus.[3][11]The split fromTroodonwas supported by Russell in 1948, who described a theropod dentary with teeth almost identical to those ofT. formosus.[12]

In 1953,Birger BohlinnamedTroodonbexellibased on a parietal bone from China.[13]In 1964,Oskar Kuhnconsidered this as an unequivocal species ofStegoceras;S. bexelli.[14]In 1974, the Polish palaeontologistsTeresa MaryańskaandHalszka Osmólskaconcluded that the "gastralia" ofStegoceraswere ossified tendons, after identifying such structures in the tail of the pachycephalosaurHomalocephale.[9]In 1979, William Patrick Wall andPeter Galtonnamed the new speciesStegoceras browni,based on a flattened dome, formerly described as a femaleS. validusby Galton in 1971. The specific name honours Barnum Brown, who found theholotype specimen(specimen AMNH 5450 in theAmerican Museum of Natural History) in Alberta.[15]In 1983, Galton andHans-Dieter SuesmovedS. brownito its own genus,Ornatotholus(ornatusis Latin for "adorned" andtholusfor "dome" ), and considered it the first known American member of a group of "flat-headed" pachycephalosaurs, previously known from Asia.[16]In a 1987 review of the pachycephalosaurs, Sues and Galton emended the specific namevalidustovalidum,which has subsequently been used in the scientific literature. These authors synonymizedS. brevis,S. sternbergi,andS. lambeiwithS. validum,found thatS. bexellidiffered fromStegocerasin several features, and considered it an indeterminate pachycephalosaur.[3][4]In 1998, Goodwin and colleagues consideredOrnatotholusa juvenileS. validum,therefore a junior synonym.[17]

21st century developments

[edit]

In 2000, Robert M. Sullivan referredS. edmontonensisandS. brevisto the genusPrenocephale(until then only known from the Mongolian speciesP. prenes), and found it more likely thatS. bexellibelonged toPrenocephalethan toStegoceras,but considered it anomen dubium(dubious name, without distinguishing characters) due to its incompleteness, and noted its holotype specimen appeared to be lost.[18]In 2003, Thomas E. Williamson andThomas CarrconsideredOrnatotholusanomen dubium,or perhaps a juvenileStegoceras.[19]In a 2003 revision ofStegoceras,Sullivan agreed thatOrnatotholuswas a junior synonym ofStegoceras,movedS. lambeito the new genusColepiocephale,andS. sternbergitoHanssuesia.He stated that the genusStegocerashad become awastebasket taxonfor small to medium-sized North American pachycephalosaurs until that point. By this time, dozens of specimens had been referred toS. validum,including many domes too incomplete to be identified asStegoceraswith certainty. UALVP 2 is still the most complete specimen ofStegoceras,upon which most scientific understanding of the genus is based.[4]S. breviswas moved to the new genusForaminacephalein 2016 by Ryan K. Schott Schott and David C. Evans,[20]andS.bexellitoSinocephalein 2021 by Evans and colleagues.[21]In 2023, Aaron D. Dyer and colleagues analysed sutures and individual elements in the skulls of the pachycephalosaursGravitholusandHanssuesia,and found no significant distinction between them andStegoceras validum.They considered both as junior synonyms, withGravitholusrepresenting the end-stage in the growth ofStegoceras.[22]

In 2002, Williamson and Carr described a dome (specimen NMMNH P-33983 in theNew Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science) from theSan Juan Basin,New Mexico,which they considered a juvenile pachycephalosaur of uncertain species (though perhapsSphaerotholus goodwini). In 2006, Sullivan and Spencer G. Lucas considered it a juvenileS. validum,which would expand the range of the species considerably.[23][24]In2011,Steven E. Jasinski and Sullivan considered the specimen an adult, and made it the holotype of the new speciesStegoceras novomexicanum,with two other specimens (SMP VP-2555 and SMP VP-2790) as paratypes.[25]A 2011phylogenetic analysisby Watabe and colleagues did not place the twoStegocerasspecies close to each other.[26]

In 2016, Williamson andStephen L. Brusatterestudied the holotype ofS. novomexicanumand found that the paratypes did not belong to the same taxon as the holotype, and that all the involved specimens were juveniles. Furthermore, they were unable to determine whether the holotype specimen represented the distinct speciesS. novomexicanum,or if it was a juvenile of eitherS. validumorSphaerotholus goodwini,or another previously known pachycephalosaur.[27]In 2016, Jasinski and Sullivan defended the validity ofS. novomexicanum;they agreed that some features used to diagnose the species were indicative of a sub-adult stage, but presented additional diagnostic features in the holotype that distinguish the species. They also pointed out some adult features, which may indicateheterochrony(difference in timing ofontogeneticchanges between related taxa) in the species. They conceded that the paratypes and other assigned specimens differed from the holotype in having more highly domed skulls, instead referring to them ascf.S. novomexicanum(difficult to identify), but found it likely they all belonged to the same taxon (with the assigned specimens being adults), due to the restrictedstratigraphicinterval and geographic range.[28]Dyer and colleagues found that theS. novomexicanumholotype could be an immatureSphaerotholus goodwini,because the proposed unique traits ofS. novomexicanumdisappeared through ontogeny inS. validum.[22]

In 2024, a specimen ofStegocerasfrom theAguja Formationwas described, and assigned toStegocerasbased on morphometric analyses. It was a juvenile, very comparable to juveniles ofS. validum,but different in some aspects. They considered it a possible representative of a new southern species ofStegoceras,but notS. novomexicanum,since the study concluded it was very dissimilar from otherStegocerasspecimens and therefore probably not referable toStegoceras.The description also included the holotype of the dubious speciesTexacephale langstoniin its morphometric analysis,where it was also found to be very similar toS. validumbut not to the extent to which the authors of the study outright referred it to that species. Nevertheless, the authors of the study considered that the holotype ofTexacephalewas probably an adult specimen of the genusStegoceras.[29]

Description

[edit]

Stegocerasis one of the most completely known North American pachycephalosaurs, and one of the few known frompostcranialremains;S. validumspecimen UALVP 2 is the most completeStegocerasindividual known to date. Its length is estimated to have been about 2 to 2.5 metres (6.6 to 8.2 ft), comparable to the size of agoat.[30][31][32]The weight has been estimated to be about 10 to 40 kilograms (22 to 88 lb).[33]Stegoceraswas small to medium in size compared to other pachycephalosaurs.[3]S. novomexicanumappears to have been smaller thanS. validum,but it is disputed whether the known specimens (incomplete skulls) are adults or juveniles.[25][27]

Skull and dentition

[edit]

The skull ofStegoceraswas roughly triangular in shape when viewed from the side, with a relatively short snout. Thefrontalandparietal boneswere very thick and formed an elevated dome. Thesuturebetween these two elements was obliterated (only faintly visible in some specimens), and they are collectively termed the "frontoparietal". The frontoparietal dome was broad and had a relatively smooth surface, with only the sides being rugose (wrinkled). It was narrowed above and between theorbita(eye sockets). The frontoparietal narrowed at the back, was wedged between thesquamosal bones,and ended in a depression above theocciputat the back of the skull. The parietal and squamosal bones formed a thick shelf over the occiput termed the parietosquamosal shelf, whose extent varied between specimens. The squamosal was large, not part of the dome, and the back part was swollen. It was ornamented by irregularly spacedtubercles(or round outgrowths), and a row of nodes (knobs) extended along its upper edges, ending in a pointed tubercle (or small horn) on each side at the back of the skull. An inner row of smaller tubercles ran parallel with the larger one. Except for the upper surface of the dome, much of the skull was ornamented with nodes, many arranged in rows.[3]

The large orbit was shaped like an imperfect ellipse (with the longest axis from front to back), and faced to the side and slightly forward. Theinfratemporal fenestra(opening) behind the eye was narrow and sloped backwards, and thesupratemporal fenestraon the top back of the skull was very reduced in size, due to the thickening of the frontoparietal. Thebasicranium(floor of thebraincase) was shortened and distanced from the regions below the orbits and around thepalate.The occiput sloped backwards and down, and the occipital condyle was deflected in the same direction. Thelacrimal boneformed the lower front margin of the orbit, and its surface had rows of node-like ornamentation. Theprefrontalandpalpebral boneswere fused and formed a thick ridge above the orbit. The relatively largejugal boneformed the lower margin of the orbit, extending far forwards and down towards the jaw joint. It was ornamented with ridges and nodes in a radiating arrangement.[3]

The nasal openings were large and faced frontwards. Thenasal bonewas thick, heavily sculpted, and had a convex profile. It formed a Boss (shield) on the middle top of the skull together with the frontal bone. The lower front of thepremaxilla(front bone of the upper jaw) was rugose and thickened. A smallforamen(hole) was present in the suture between the premaxillae, leading into thenasal cavity,and possibly connected to theJacobson's organ(anolfactorysense organ). The maxilla was short and deep, and probably contained asinus.The maxilla had a series of foramina that corresponded with each tooth position there, and these functioned as passages for erupting replacement teeth. The mandible articulated with the skull below the back of the orbit. The tooth-bearing part of the lower jaw was long, with the part behind being rather short. Though not preserved, the presence of apredentary boneis indicated by facets at the front of the lower jaw.[3]Like other pachycephalosaurs, it would have had a small beak.[34]

Stegocerashad teeth that wereheterodont(differentiated) andthecodont(placed in sockets). It had marginal rows of relatively small teeth, and the rows did not form a straight cutting edge. The teeth were set obliquely along the length of the jaws, and overlapped each other slightly from front to back. On each side, the most complete specimen (UALVP 2) had three teeth in the premaxilla, sixteen in themaxilla(both part of the upper jaw), and seventeen in thedentaryof the lower jaw. The teeth in the premaxilla were separated from those behind in the maxilla by a shortdiastema(space), and the two rows in the premaxilla were separated by a toothless gap at the front. The teeth in the front part of the upper jaw (premaxilla) and front lower jaw were similar; these had taller, more pointed and recurved crowns, and a "heel" at the back. The front teeth in the lower jaw were larger than those of the upper jaw. The front edges of the crowns bore eightdenticles(serrations), and the back edge bore nine to eleven. The teeth in the back of the upper (maxilla) and lower jaw were triangular in side view and compressed in front view. They had long roots that were oval in section, and the crowns had a markedcingulumat their bases. The denticles here were compressed and directed towards the top of the crowns. Both the outer and inner side of thetooth crownsboreenamel,and both sides were divided vertically by a ridge. Each edge had about seven or eight denticles, with the front edge usually having the most.[3]

The skull ofStegocerascan be distinguished from those of other pachycephalosaurs by features such as its pronounced parietosquamosal shelf (though this became smaller with age), the "incipient" doming of its frontopariental (though the doming increased with age), its inflated nasal bones, its ornamentation of tubercles on the sides and back of the squamosal bones, rows of up to six tubercles on the upper side of each squamosal, and up to two nodes on the backwards projection of the parietal. It is also distinct in its lack of nasal ornamentation, and in having a reduced diastema.[4][35]The skull ofS. novomexicanumcan be distinguished from that ofS. validumin features such as the backwards extension of the parietal bone being more reduced and triangular, having larger supratemporal fenestrae (though this may be due to the possible juvenile status of the specimens), and having roughly parallel suture contacts between the squamosal and parietal. It also appears to have had a smaller frontal Boss thanS. validum,[25][27]and seems to have been more gracile overall.[28]

Postcranial skeleton

[edit]Thevertebral columnofStegocerasis incompletely known. The articulation between thezygagophyses(articular processes) of successive dorsal (back) vertebrae appears to have prevented sideways movement of the vertebral column, which made it very rigid, and it was further strengthened byossified tendons.[3]Though the neck vertebrae are not known, the downturnedoccipital condyle(which articulates with the first neck vertebra) indicates that the neck was held in a curved posture, like the "S" - or "U" -shape of most dinosaur necks.[36]Based on their position inHomalocephale,the ossified tendons found with UALVP 2 would have formed an intricate "caudal basket"in the tail, consisting of parallel rows, with the extremities of each tendon contacting the next successively. Such structures are calledmyorhabdoi,and are otherwise only known inteleost fish;the feature is unique to pachycephalosaurs amongtetrapod(four-limbed) animals, and may have functioned in stiffening the tail.[9]

Thescapula(shoulder blade) was longer than thehumerus(upper arm bone); its blade was slender and narrow, and slightly twisted, following the contour of the ribs. The scapula did not expand at the upper end but was very expanded at the base. Thecoracoidwas mainly thin and plate-like. The humerus had a slender shaft, was slightly twisted along its length, and was slightly bowed. Thedeltopectoral crest(where thedeltoidandpectoralmuscles attached) was weakly developed. The ends of theulnawere expanded, and ridges extended along the shaft. Theradiuswas more robust than the ulna, which is unusual. When seen from above, thepelvic girdlewas very broad for abipedalarchosaur,and became wider towards the hind part. The broadness of the pelvic region may have accommodated a rear extension of the gut. Theiliumwas elongated and theischiumwas long and slender. Though thepubisis not known, it was probably reduced in size like that ofHomalocephale.Thefemur(thigh bone) was slender and inwards curved, the tibia was slender and twisted, and thefibulawas slender and wide at the upper end. Themetatarsusof the foot appears to have been narrow, and the single knownungual(claw bone) of a toe was slender and slightly curved.[3]Though the limbs ofStegocerasare not completely known, they were most likely like other pachycephalosaurs in having five-fingered hands and four toes.[34]

Classification

[edit]

During the 1970s, more pachycephalosaur genera were described from Asian fossils, which provided more information about the group. In 1974, Maryańska and Osmólska concluded that pachycephalosaurs are distinct enough to warrant their ownsuborderwithin Ornithischia, Pachycephalosauria. In 1978, the Chinese palaeontologistDong Zhimingsplit Pachycephalosauria into two families; the dome-headed Pachycephalosauridae (includingStegoceras) and the flat-headed Homalocephalidae (originally spelled Homalocephaleridae).[37]Wall and Galton did not find suborder status for the pachycephalosaurs justified in 1979.[15]By the 1980s, the affinities of the pachycephalosaurs within Ornithischia were unresolved. The main competing views were that the group was closest to either ornithopods or ceratopsians, the latter view due to similarities between the skeleton ofStegocerasand the "primitive" ceratopsianProtoceratops.In 1986, American palaeontologistPaul Serenosupported the relationship between pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians, and united them in the groupMarginocephalia,based on similar cranial features, such as the "shelf" -structure above the occiput. He conceded that the evidence for this grouping was not overwhelming, but the validity of the group was supported by Sues and Galton in 1987.[3]

By the early 21st century, few pachycephalosaur genera were known from postcranial remains, and many taxa were only known from domes, which made classification within the group difficult. Pachycephalosaurs are thus mainly defined by cranial features, such as the flat to domed frontoparietal, the broad and flattened bar along the postorbital and squamosal bones, and the squamosal bones being deep plates on the occiput.[32]In 1986, Sereno had divided the pachycephalosaurs into different groups based on the extent of the doming of their skulls (grouped in now invalid taxa such as "Tholocephalidae" and "Domocephalinae" ), and in 2000 he considered the "partially" domedStegocerasa transition between the supposedly "primitive" flat-headed and advanced "fully" domed genera (such asPachycephalosaurus).[38]The dome-headed/flat-headed division of the pachycephalosaurs was abandoned in the following years, as flat heads were consideredpaedomorphic(juvenile-like) or derived traits in most revisions, but not a sexuallydimorphictrait. In 2006, Sullivan argued against the idea that the extent of doming was useful in determining taxonomic affinities between pachycephalosaurs.[32]In 2003, Sullivan foundStegocerasitself to be morebasal(or "primitive" ) than the "fully-domed" members of the subfamily Pachycephalosaurinae, elaborating on conclusions reached by Sereno in 1986.[4]

A 2013phylogenetic analysisby Evans and colleagues found that some flat-headed pachycephalosaur genera were more closely related to "fully" domed taxa than to the "incompletely" domedStegoceras,which suggests they represent juveniles of domed taxa, and that flat heads do not indicate taxonomic affinities.[39]Thecladogrambelow shows the placement ofStegoceraswithin Pachycephalosauridae according to Schott and colleagues, 2016:[20]

| Pachycephalosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thebiogeographyand early evolutionary history of pachycephalosaurs is poorly understood, and can only be clarified by new discoveries. Pachycephalosaurs appear abruptly in the fossil record, and are present in both North America and Asia, so it is unknown when they first originated, and from which direction they dispersed. The oldest known members of the group (such asAcrotholus) are "fully domed" and known from theSantonianstage of the Late Cretaceous period (about 84 million years ago). This is before the supposedly more primitiveStegocerasfrom theMiddle Campanian(77 million years ago) andHomalocephalefrom theEarly Maastrichtian(70 million years ago), so the doming of the skull may be a homoplastic trait (a form ofconvergent evolution). The late occurrence of pachycephalosaurs compared to the related ceratopsians indicates a longghost lineage(inferred, but missing from the fossil record) spanning 66 million years, from theLate Jurassicto the Cretaceous. Since pachycephalosaurs were mainly small, this may be due totaphonomic bias;smaller animals are less likely to be preserved through fossilisation. More delicate bones are also less likely to be preserved, which is why pachycephalosaurs are mainly known from their robust skulls.[4][39]

Palaeobiology

[edit]Feeding mechanics

[edit]

It is uncertain what pachycephalosaurs ate; having very small, ridged teeth they could not have chewed tough, fibrous plants as effectively as other dinosaurs of the same period. It is assumed that their sharp, serrated teeth were ideally suited for a mixed diet of leaves, seeds, fruit and insects.[40]Stegocerasmay have had an entirely herbivorous diet, as the tooth crowns were similar to those ofiguanidlizards. The premaxillary teeth show wear facets from contact with the predentary bone, and the maxillary teeth have double wear facets similar to those seen in other ornithischian dinosaurs. Every third maxillary tooth of UALVP 2 are eruptingreplacement teeth,and tooth replacement happened in backwards progression in sequential threes. The occipital region ofStegoceraswas well-demarcated for muscle-attachment and it is believed that the jaw movement ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs was mostly limited to up-and-down motions with only a slight capability for jaw rotation. This is based on the structure of the jaw and dental microwear and wear facets of the teeth indicate that the bite-force was used more for shearing than for crushing.[3][41]

In 2021, the Canadian palaeontologist Michael N. Hudgins and colleagues examined the teeth ofStegocerasandThescelosaurusand found that while both had heterodont teeth, they could be statistically distinguished from each other. Due to its broad rostrum and more uniform teeth,Stegoceraswas an indiscriminate bulk-feeder that cropped large amounts of vegetation, while the teeth and narrow rostrum ofThescelosaurusindicates it was a selective feeder. Pachycephalosaurs and Thescelosaurids occur in the same North American formations, and it appears that their coexistence was made possible by them occupying differentecomorphospaces(thoughStegocerasandThescelosaurusthemselves were not contemporaries).[42]

Nasal passages

[edit]In 1989, Emily B. Griffin found thatStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs had a good sense of smell (olfaction), based on the study of cranialendocaststhat showed largeolfactory bulbsin the brain.[43]In 2014, Jason M. Bourke and colleagues found thatStegoceraswould have needed cartilaginousnasal turbinatesin the front of the nasal passages for airflow to reach the olfactory region. Evidence for the presence of this structure is a bony ridge to which it could have attached. The size of the olfactory region also indicates thatStegocerashad a keen sense of smell. The researchers found that the dinosaur could have had either a scroll-shaped turbinate (like in aturkey) or a branched one (as in anostrich) as both could have directed air to the olfactory region. The blood vessel system in the passages also suggest that the turbinates served to cool down warm arterial blood from the body that was heading to the brain. The skull ofS. validumspecimen UALVP 2 was suited for a study of this kind due to its exceptional preservation; it has ossified soft tissue in the nasal cavity, which would otherwise becartilaginousand therefore not preserved through mineralization.[44]

Ontogenetic changes

[edit]

Several explanations have historically been proposed for the variation seen in the skulls ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs. Brown and Schlaikjer suggested that there wassexual dimorphismin the degree of doming, and hypothesized that flat-headed specimens such as AMNH 5450 (Ornatotholus) represented the female morph ofStegoceras.This idea was supported by a 1981morphometricstudy by Champan and colleagues, which found that males had larger and thicker domes.[35][45]After other flat-headed pachycephalosaurs were discovered, the degree of doming was proposed to be a feature with taxonomic importance, and AMNH 5450 was therefore considered a distinct taxon from 1979 onwards. In 1998, Goodwin and colleagues instead proposed that the inflation of the dome was an ontogenetic feature that changed with age, based on ahistologicalstudy of anS. validumskull that showed the dome consisted of vascular, fast-growing bone, consistent with an increase in doming through age. These authors found that the supposedly distinct features ofOrnatotholuscould easily be the results of ontogeny.[35][17]

In 2003, Williamson and Carr published a hypothetical growth series ofS. validum,showingOrnatotholusas the juvenile stage. They suggested that juveniles were characterized by a flat, thickened frontoparietal roof, with larger supratemporal fenestrae, and studded with closely spaced tubercles and nodes. The parietosquamosal shelf was not reduced in size, and the frontoparietal suture was open. Sub-adults had mound-like domes, with the back part of the parietal and skull-roof being flat. The supratemporal fenestrae showed asymmetry in size, and the closure of the frontoparietal suture was variable. The nodes were stretched or almost obliterated as the dome expanded during growth, with a tesserated surface remaining. The pattern was often obliterated at the highest point (apex) of the dome, the area where maximum expansion occurred. The tubercles on the skull were stretched in different directions, and those at the margin of the parietosquamosal shelf may have beenhypertrophied(enlarged) tubercles. The back and sides of sub-adult and adult skulls were ornamented by less modified tubercles. Before being incorporated into the enlarging dome, the skull bones expanded, resulting in junctions between these bones. The adult dome was broad and convex, and incorporated most of the shelf, which was reduced in size and overhung the occiput as a thick "lip". The supratempooral fenestrae were closed, but the suture between the frontoparietal and connected skull bones was not always closed in adults and subadults.[19]

In 2011, Schott and colleagues made a more comprehensive analysis of cranial dome ontogeny inS. validum.The study found that the parietosquamosal shelf conserved the arrangement of ornamentation throughout growth, and that vascularity of the frontoparietal domes decreased with size. It also found that dome shape and size was strongly correlated with growth, and that growth wasallometric(in contrast toisometric) from flat to domed, supportingOrnatotholusas a juvenileStegoceras.They also hypothesized that this model of dome growth, with dramatic changes from juvenile to adult, was the common developmental trajectory of pachycephalosaurs. These researchers noted that though Williamson and Carr's observation that the supratemporal fenestrae closed with age was generally correct, there was still a high degree of individual variation in the size of these fenestrae, regardless of the size of the frontoparietal, and this feature may therefore have been independent of ontogeny.[35]

A 2012 study by Schott and Evans found that the number and shape of the individual nodes on the squamosal shelf of the examinedS. validumskulls varied considerably, and that this variability does not seem to correlate with ontogenic changes, but was due to individual variation. These researchers found no correlation between the width of supratemporal fenestrae and the size of the squamosal.[46]

Dome function

[edit]The function of pachycephalosaur domes has been debated, andStegocerashas been used as a model for experimentation in various studies. The dome has mainly been interpreted as a weapon used inintra-specific combat,asexual displaystructure, or a means forspecies recognition.[47][48]

Combat

[edit]

The hypothesis that the domed skulls ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs were used for butting heads was first suggested by American palaeontologistEdwin Colbertin 1955. In 1970 and 1971, Galton elaborated on this idea, and argued that if the dome was simply ornamental, it would have been less dense, and that the structure was ideal for resisting force. Galton suggested that whenStegocerasheld its skull vertically, perpendicular to the neck, force would be transmitted from the skull, with little chance of it being dislocated, and the dome could therefore be used as a battering-ram. He believed it was unlikely to have been used mainly as defence against predators, because the dome itself lacked spikes, and those of the parietosquamosal shelf were in an "ineffective" position, but found it compatible with intra-specific competition. Galton imagined the domes were bashed together, while the vertebral column was held in a horizontal position. This could either be done while facing each other while dealing blows, or while charging each other with lowered heads (analogous to modern sheep and goats). He also noted that the rigidity of the back would have been useful when using the head for this purpose. In 1978, Sues agreed with Galton that the anatomy of pachycephalosaurs was consistent with transmitting dome-to-dome impact stress, based on tests withplexi-glassmodels. The impact would be absorbed through the neck and body, and neck ligaments and muscles would prevent injuries by glancing blows (as in modernbighorn sheep). Sues also suggested that the animals could have butted each other's flanks.[36][49][50]

In 1997, the American palaeontologistKenneth Carpenterpointed out that the dorsal vertebrae from the back of the pachycephalosaurHomalocephaleshow that the back curved downwards just before the neck (which was not preserved), and unless the neck curved upwards, the head would point to the ground. He therefore inferred that the necks ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs were held in a curved posture (as is the norm in dinosaurs), and that they would therefore not have been able to align their head, neck, and body horizontally straight, which would be needed to transmit stress. Their necks would have to be held below the level of the back, which would have risked damaging the spinal cord on impact. Modern bighorn sheep andbisonovercome this problem by having strong ligaments from the neck to the tall neural spines over the shoulders (which absorb the force of impact), but such features are not known in pachycephalosaurs. These animals also absorb the force of impact through sinus chambers at the base of their horns, and their foreheads and horns form a broad contact surface, unlike the narrow surface of pachycephalosaur domes. Because the dome ofStegoceraswas rounded, it would have given a very small area for potential impact, and the domes would have glanced off each other (unless the impact was perfectly centred). Combating pachycephalosaurs would have had difficulty seeing each other while their heads were lowered, due to the bony ridges above the eyes.[36]

Because of the problems he found with the head-butting hypothesis, Carpenter instead suggested the domes were adaptations for flank-butting (as seen in some large African mammals); he imagined that two animals would stand parallel, facing each other or the same direction, and direct blows to the side of the opponent. The relatively large body width of pachycephalosaurs may consequently have served to protect vital organs from harm during flank-butting. It is possible thatStegocerasand similar pachycephalosaurs would have delivered the blows with a movement of the neck from the side and a rotation of the head. The upper sides of the dome have the greatest surface area, and may have been the point of impact. The thickness of the dome would have increased the power behind a blow to the sides, and this would ensure that the opponent felt the force of the impact, without being seriously injured. The bone rim above the orbit may have protected the aggressor's eye when making a blow. Carpenter suggested that the pachycephalosaurs would have first engaged inthreat displayby bobbing and presenting their heads to show the size of their domes (intimidation), and thereafter delivered blows to each other, until one opponent signalled submission.[36]

In 2008, Eric Snively and Adam Cox tested the performance of 2D and 3D pachycephalosaur skulls throughfinite element analysis,and found that they could withstand considerable impact; greater vaulting of the domes allowed for higher forces of impact. They also considered it likely that pachycephalosaur domes were covered inkeratin,a strong material that can withstand much energy without being permanently damaged (like theosteodermsofcrocodilians), and therefore incorporated keratin into their test formula.[51]In 2011, Snively and Jessica M. Theodor conducted a finite element analysis by simulating head-impacts withCT scannedskulls ofS. validum(UALVP 2),Prenocephale prenesand several extant head-buttingartiodactyls.They found that the correlations between head-striking and skull morphologies found in the living animals also existed in the studied pachycephalosaurs.StegocerasandPrenocephaleboth had skull shapes similar to the bighorn sheep withcancellous boneprotecting the brain. They also shared similarities in the distribution of compact and cancellous regions with the bighorn sheep,white-bellied duikerand thegiraffe.The white-bellied duiker was found to be the closest morphological analogue toStegoceras;this head-butting species has a dome which is smaller but similarly rounded.Stegoceraswas better capable of dissipating force than artiodactyls that butt heads at high forces, but the less vascularized domes of older pachycephalosaurs, and possibly diminished ability to heal from injuries, argued against such combat in older individuals. The study also tested the effects of a keratinous covering of the dome, and found it to aid in performance. ThoughStegoceraslacked thepneumaticsinuses that are found below the point of impact in the skulls of head-striking artiodactyls, it instead had vascular struts which could have similarly acted as braces, as well as conduits to feed the development of a keratin covering.[52]

In 2012, Caleb M. Brown and Anthony P. Russell suggested that the stiffened tails were probably not used as defence against flank-butting, but may have enabled the animals to take a tripodal stance during intra-specific combat, with the tail as support. Brown and Russell found that the tail could thereby help in resisting compressive, tensile, and torsional loading when the animal delivered or received blows with the dome.[9]A 2013 study by Joseph E. Peterson and colleagues identified lesions in skulls ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs, which were interpreted as infections caused by trauma. Lesions were found on 22% of sampled pachycephalosaur skulls (a frequency consistent across genera), but were absent from flat-headed specimens (which have been interpreted as juveniles or females), which is consistent with use in intra-specific combat (for territory or mates). The distribution of lesions in these animals tended to concentrate at the top of the dome, which supports head-butting behaviour. Flank-butting would probably result in fewer injuries, which would instead be concentrated on the sides of the dome. These observations were made while comparing the lesions with those on the skulls and flanks of modern sheep skeletons. The researchers noted that modern head-butting animals use their weapons for both combat and display, and that pachycephalosaurs could therefore also have used their domes for both. Displaying a weapon and willingness to use it can be enough to settle disputes in some animals.[47]

Bryan R. S. Moore and colleagues examined and reconstructed the limb musculature ofStegocerasin 3D in 2022, using the very complete UALVP 2 specimen as basis. They found that the musculature of the forelimbs was conservative, particularly compared to those of early bipedalsaurischiandinosaurs, but the pelvic and hindlimb musculature was instead morederived(or "advanced" ), due to peculiarities of the skeleton. These areas had large muscles, and combined with the wide pelvis and stout hind limbs (and possibly enlarged ligaments), this resulted in a strong, stable pelvic structure that would have helped during head-butting between individuals. Since the skull domes of pachycephalosaurs grew withpositive allometry,and may have been used in combat, these researchers suggested it may have been the case for the hindlimb muscles as well, if they were used to propel the body forwards during head-butting. They cautioned that while UALVP 2 is very complete for a pachycephalosaur, their study was limited by it missing large portions of its vertebral column and outer limb elements.[53]

Other suggested functions

[edit]

In 1987, J. Keith Rigby and colleagues suggested that pachycephalosaur domes wereheat-exchangeorgans used forthermoregulation,based on their internal "radiating structures" (trabeculae). This idea was supported by a few other writers in the mid-1990s.[48]In 1998, Goodwin and colleagues considered the lack of sinuses in the skull ofStegocerasand the "honeycomb"-like network of vascular bone in the dome ill-suited for head-butting, and pointed out that the bones adjacent to the dome risked fracture during such contact. Building on the idea that the ossified tendons that stiffened the tails ofStegocerasand other pachycephalosaurs enabled them to take a tripodal stance (first suggested by Maryańska and Osmólska in 1974), Goodwin et al. suggested these structures could have protected the tail against flank-butting, or that the tail itself could have been used as a weapon.[17]In 2004, Goodwin and colleagues studied the cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs, and found that the vascularity (including the trabeculae) of the domes decreased with age, which they found inconsistent with a function in either head-butting or heat-exchange. They also suggested that a dense layer ofSharpey's fibersnear the surface of the dome indicated that it had an external covering in life, which makes it impossible to know the shape of the dome in a living animal. These researchers instead concluded that the domes were mainly for species recognition and communication (as in some Africanbovids) and that use in sexual display was only secondary. They further speculated that the external covering of the domes was brightly coloured in life, or may have changed colour seasonally.[48]

In 2011, American palaeontologistsKevin PadianandJohn R. Hornerproposed that "bizarre structures" in dinosaurs in general (including domes, frills, horns, and crests) were primarily used for species recognition, and dismissed other explanations as unsupported by evidence. Among other studies, these authors cited Goodwin et al.'s 2004 paper on pachycephalosaur domes as support of this idea, and they pointed out that such structures did not appear to be sexually dimorphic.[54]In a response to Padian and Horner the same year, Rob J. Knell andScott D. Sampsonargued that species recognition was not unlikely as a secondary function for "bizarre structures" in dinosaurs, but thatsexual selection(used in display or combat to compete for mates) was a more likely explanation, due to the high cost of developing them, and because such structures appear to be highly variable within species.[55]In 2013, the British palaeontologists David E. Hone andDarren Naishcriticized the "species recognition hypothesis", and argued that no extant animals use such structures primarily for species recognition, and that Padian and Horner had ignored the possibility of mutual sexual selection (where both sexes are ornamented).[56]

In 2012, Schott and Evans suggested that the regularity in squamosal ornamentation throughout the ontogeny ofStegoceraswas consistent with species recognition, but the change from flat to domed frontoparietals in late age suggests that the function of this feature changed through ontogeny, and was perhaps sexually selected, possibly for intra-specific combat.[46]Dyer and colleagues found in 2023 thatStegocerasspecimens differed in the thickness of the frontonasal Boss, and that skulls with the most bone pathologies were those with the tallest Boss es, which they considered indication that variation in Boss thickness represents intersexual variation.[22]In 2023, Horner and colleagues stated that since the dome and associated ornamentation ofStegocerasand the ornamentation ofPachycephalosaurusdeveloped early in life, this indicates they were used for visual communication, so that juveniles could recognise other juveniles and adults other adults. They did not rule out that these features could have been used for other purposes, including head-butting, but did not consider trauma seen in specimens as evidence for this. They also suggested that features in some pachycephalosaurid skulls indicate the dome would have supported a greater, keratinous structure than just a cap.[57]

Palaeoenvironment

[edit]

S. validumis known from the lateLate CretaceousBelly River Group (the Canadian equivalent to theJudith River Groupin the US), and specimens have been recovered from theDinosaur Park Formation(late Campanian, 76.5 to 75 mya) inDinosaur Provincial Park(including the lectotype specimen), and theOldman Formation(middle Campanian, 77.5 to 76.5 mya) of Alberta, Canada. The pachycephalosaursHanssuesia(if not a synonym ofStegoceras) andForaminacephaleare also known from both formations.[4][22]S. novomexicanumis known from theFruitland(late Campanian, about 75 mya) and lowerKirtland Formation(lateCampanian,about 74 mya) of New Mexico, and if this species correctly belongs inStegoceras,the genus would have had a broad geographic distribution.[25]The presence of similar pachycephalosaurs in both the west and north of North America during the latest Cretaceous shows that they were an important part of the dinosaur faunas there.[27]

It has traditionally been suggested that pachycehalosaurs inhabited mountain environments; wear of their skulls was supposedly a result of them having been rolled by water from upland areas, and comparisons with bighorn sheep reinforced the theory. In 2014, Jordan C. Mallon and Evans disputed this idea, as the wear and original locations of the skulls is not consistent with having been transported in such a way, and they instead proposed that North American pachycephalosaurs inhabitedalluvial(associated with water) andcoastal plainenvironments.[58]

The Dinosaur Park Formation is interpreted as a low-relief setting ofriversandfloodplainsthat became moreswampyand influenced bymarineconditions over time as theWestern Interior Seawaytransgressedwestward.[59]Theclimatewas warmer than present-day Alberta, withoutfrost,but with wetter and drier seasons.Coniferswere apparently the dominantcanopyplants, with anunderstoryofferns,tree ferns,andangiosperms.[60]Dinosaur Park is known for its diverse community of herbivores. As well asStegoceras,the formation has also yielded fossils of the ceratopsiansCentrosaurus,StyracosaurusandChasmosaurus,thehadrosauridsProsaurolophus,Lambeosaurus,Gryposaurus,Corythosaurus,andParasaurolophus,and theankylosaursEdmontoniaandEuoplocephalus.Theropods present include thetyrannosauridsGorgosaurusandDaspletosaurus.[61]Other dinosaurs known from the Oldman Formation include the hadrosaurBrachylophosaurus,the ceratopsiansCoronosaurusandAlbertaceratops,ornithomimids,therizinosaursand possibly ankylosaurs. Theropods includedtroodontids,oviraptorosaurs,thedromaeosauridSaurornitholestesand possibly an albertosaurine tyrannosaur.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abLambe, L. M. (1902)."New genera and species from the Belly River Series (mid-Cretaceous)".Geological Survey of Canada, Contributions to Canadian Palaeontology.3:68.

- ^abcHatcher, J.B.; Lull, R.S.; Marsh, O.C.; Osborn, H. F. (1907)."The Ceratopsia".Monographs of the United States Geological Survey.XLIX.doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60500.

- ^abcdefghijklSues, H. D. & Galton, P. M. (1987)."Anatomy and classification of the North American Pachycephalosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)".Palaeontographica Abteilung A.198:1–40.

- ^abcdefgSullivan, R. M. (2003). "Revision of the dinosaurStegocerasLambe (Ornithischia, Pachycephalosauridae) ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.23(1): 181–207.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[181:rotdsl]2.0.co;2.S2CID85894105.

- ^Nopcsa, F. (1903). "ÜberStegocerasundStereocephalus".Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie.1903:266–267.

- ^Lambe, L.M. (1903)."Recent Zoopaleontology".Science.18(445): 60.Bibcode:1903Sci....18...60L.doi:10.1126/science.18.445.60.JSTOR1631645.PMID17746863.

- ^Lambe, L. M. (1918)."The Cretaceous genusStegocerastypifying a new family referred provisionally to the Stegosauria ".Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada.12(4): 23–36.

- ^Gilmore, C. W. (1924). "OnTroodon validus,an orthopodous dinosaur from the Belly River Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada ".Department of Geology, University of Alberta Bulletin.1:1–43.

- ^abcdBrown, C. M.; Russell, A. P.; Farke, A. A. (2012)."Homology and Architecture of the Caudal Basket of Pachycephalosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia): The First Occurrence of Myorhabdoi in Tetrapoda".PLOS ONE.7(1): e30212.Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730212B.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030212.PMC3260247.PMID22272307.

- ^abBrown, B.; E. M., Schlaikjer (1943). "A study of the troödont dinosaurs, with the description of a new genus and four new species".Bulletin of the AMNH.82.hdl:2246/387.

- ^Sternberg, C. M. (1945). "Pachycephalosauridae Proposed for Dome-Headed Dinosaurs,Stegoceras lambei,n. sp., Described ".Journal of Paleontology.19(5): 534–538.JSTOR1299007.

- ^Russell, L. S. (1948). "The dentary ofTroödon,a genus of theropod dinosaurs ".Journal of Paleontology.22(5): 625–629.JSTOR1299599.

- ^Bohlin, B., 1953. Fossil reptiles from Mongolia and Kansu. Reports from the Scientific Expedition to the North-western Provinces of China under Leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin. VI. Vertebrate Palaeontology 6. The Sino-Swedish Expedition Publication 37:1–113

- ^Kuhn, O., 1964,Fossilium Catalogus I: Animalia Pars 105. Ornithischia (Supplementum I),IJsel Pers, Deventer, 80 pp

- ^abWall, W. P.; Galton, P. M. (1979). "Notes on pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithischia) from North America, with comments on their status as ornithopods".Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.16(6): 1176–1186.Bibcode:1979CaJES..16.1176W.doi:10.1139/e79-104.

- ^Galton, P. M.; Sues, H.-D. (1983). "New data on pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithischia) from North America".Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.20(3): 462–472.Bibcode:1983CaJES..20..462G.doi:10.1139/e83-043.

- ^abcGoodwin, M. B.; Buchholtz, E. A.; Johnson, R. E. (1998). "Cranial anatomy and diagnosis ofStygimoloch spinifer(Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauria) with comments on cranial display structures in agonistic behavior ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.18(2): 363–375.Bibcode:1998JVPal..18..363G.doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011064.

- ^Sullivan, Robert M. (2000)."Prenocephale edmontonensis(Brown and Schlaikjer) new comb. andP. brevis(Lambe) new comb. (Dinosauria: Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of North America ".New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin.17:177–90.

- ^abWilliamson, T. E.; Carr, T. D. (2003). "A new genus of derived pachycephalosaurian from western North America".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.22(4): 779–801.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0779:ANGODP]2.0.CO;2.S2CID86112901.

- ^abSchott, R. K.; Evans, D. C. (2016). "Cranial variation and systematics ofForaminacephale brevisgen. nov. and the diversity of pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Cerapoda) in the Belly River Group of Alberta, Canada ".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.doi:10.1111/zoj.12465.

- ^Evans, David C.; Brown, Caleb M.; You, Hailu; Campione, Nicolás E. (October 2021). "Description and revised diagnosis of Asia's first recorded pachycephalosaurid, Sinocephale bexelli gen. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China".Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.58(10): 981–992.Bibcode:2021CaJES..58..981E.doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0190.S2CID244227050.

- ^abcdDyer, Aaron; Powers, Mark; Currie, Philip (2023)."Problematic putative pachycephalosaurids: Synchrotron µCT imaging shines new light on the anatomy and taxonomic validity ofGravitholus albertaefrom the Belly River Group (Campanian) of Alberta, Canada ".Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology.10(1).doi:10.18435/vamp29388.

- ^Sullivan, R. M.; Lucas, S. G. (2006)."The pachycephalosaurid dinosaurStegoceras validumfrom the Upper Cretaceous Fruitland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico ".New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin.35:329–330.

- ^Williamson, T. E.; Carr, T. D. (2002). "A juvenile pachycephalosaur (Dinosauria: Pachycephalosauridae) from the Fruitland Formation".New Mexico: New Mexico Geology.24:67–68.

- ^abcdJasinski, S. E.; Sullivan, R. M. (2011)."Re-evaluation of pachycephalosaurids from the Fruitland-Kirtland transition (Kirtlandian, late Campanian), San Juan Basin, New Mexico, with a description of a new species ofStegocerasand a reassessment ofTexascephale langstoni"(PDF).Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin.53:202–215.

- ^Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Sullivan, R. M. (2011)."A new pachycephalosaurid from the Baynshire Formation (Cenomanian-late Santonian), Gobi Desert, Mongolia"(PDF).Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin.53:489–497.

- ^abcdWilliamson, T. E.; Brusatte, S. L. (2016)."Pachycephalosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous (upper Campanian) of New Mexico: A reassessment ofStegoceras novomexicanum".Cretaceous Research.62:29–43.Bibcode:2016CrRes..62...29W.doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.01.012.

- ^abJasinski, S. E.; Sullivan, R. M. (2016)."The validity of the Late Cretaceous pachycephalosauridStegoceras novomexicanum(Dinosauria: Pachycephalosauridae) ".In Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.).Fossil Record 5: Bulletin 74.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 107–116.

- ^Wick, Steven L.; Lehman, Thomas M. (19 September 2024). "A rare 'flat-headed' pachycephalosaur (Dinosauria: Pachycephalosauridae) from West Texas, USA, with morphometric and heterochronic considerations".Geobios.86:89–106.doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2024.08.006.ISSN0016-6995.

- ^Glut, D. F.(1997).Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia.Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 834–838.ISBN978-0-89950-917-4.

- ^Lambert, D. (1993).The Ultimate Dinosaur Book.New York: Dorling Kindersley. p.155.ISBN978-1-56458-304-8.

- ^abcSullivan, R. M. (2006)."A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)".New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin.35:347–365.S2CID4243316.

- ^Peczkis, J. (1995). "Implications of Body-Mass Estimates for Dinosaurs".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.14(4): 520–533.Bibcode:1995JVPal..14..520P.doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011575.JSTOR4523591.

- ^abPaul, G. S.(2010).The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs.Princeton University Press. pp.241–242.ISBN978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^abcdSchott, Ryan K.; Evans, David C.; Goodwin, Mark B.; Horner, John R.; Brown, Caleb Marshall; Longrich, Nicholas R. (29 June 2011)."Cranial Ontogeny inStegoceras validum(Dinosauria: Pachycephalosauria): A Quantitative Model of Pachycephalosaur Dome Growth and Variation ".PLOS ONE.6(6): e21092.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621092S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021092.PMC3126802.PMID21738608.

- ^abcdCarpenter, Kenneth (1 December 1997)."Agonistic behavior in pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia, Dinosauria); a new look at head-butting behavior".Rocky Mountain Geology.32(1): 19–25.

- ^Perle, A.; Osmólska, H. (1982)."Goyocephale lattimoreigen. et sp. n., a new flat-headed pachycephalosaur (Ornlthlschia, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica ".Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.27:115–127.

- ^Sereno, P. C., 2000. The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia. 480–516 in Benton, M.J., M.A. Shishkin, D.M. Unwin & E.N. Kurochkin (eds.),The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia.Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ^abEvans, D. C.; Schott, R. K.; Larson, D. W.; Brown, C. M.; Ryan, M. J. (2013)."The oldest North American pachycephalosaurid and the hidden diversity of small-bodied ornithischian dinosaurs".Nature Communications.4:1828.Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1828E.doi:10.1038/ncomms2749.PMID23652016.

- ^Maryańska, T.; Chapman, R. E.; Weishampel, D. B. (2004). "Pachycephalosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.).The Dinosauria(2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp.464–477.ISBN978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^Nabavizadeh, A. (2016)."Evolutionary Trends in the Jaw Adductor Mechanics of Ornithischian Dinosaurs".The Anatomical Record.299(3): 271–294.doi:10.1002/ar.23306.PMID26692539.

- ^Hudgins, Michael Naylor; Currie, Philip J.; Sullivan, Corwin (16 October 2021). "Dental assessment ofStegoceras validum(Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae) andThescelosaurus neglectus(Ornithischia: Thescelosauridae): paleoecological inferences ".Cretaceous Research.130:105058.doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105058.S2CID239253658.

- ^Giffin, E. B. (1989). "Pachycephalosaur Paleoneurolagy (Archosauria: Ornithischia)".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.9(1): 67–77.Bibcode:1989JVPal...9...67G.doi:10.1080/02724634.1989.10011739.JSTOR4523238.

- ^Bourke, J. M.; Porter, Wm. R.; Ridgely, R. C.; Lyson, T. R.; Schachner, E. R.; Bell, P. R.; Witmer, L. M. (2014)."Breathing life into dinosaurs: tackling challenges of soft-tissue restoration and nasal airflow in extinct species".Anatomical Record.297(11): 2148–2186.doi:10.1002/ar.23046.PMID25312371.S2CID4660680.

- ^Chapman, R. E.; Galton, Pe. M.; Sepkoski, J. J.; Wall, W. P. (1981). "A Morphometric Study of the Cranium of the Pachycephalosaurid DinosaurStegoceras".Journal of Paleontology.55(3): 608–618.JSTOR1304275.

- ^abSchott, R. K.; Evans, D. C. (2012). "Squamosal Ontogeny and Variation in the Pachycephalosaurian DinosaurStegoceras validumLambe, 1902, from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.32(4): 903–913.Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..903S.doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.679878.JSTOR23251281.S2CID84526252.

- ^abPeterson, J. E.; Dischler, C.; Longrich, N. R.; Dodson, P. (2013)."Distributions of Cranial Pathologies Provide Evidence for Head-Butting in Dome-Headed Dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae)".PLOS ONE.8(7): e68620.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868620P.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068620.PMC3712952.PMID23874691.

- ^abcGoodwin, M. B.; Horner, J. R. (2004)."Cranial Histology of Pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Marginocephalia) Reveals Transitory Structures Inconsistent with Head-Butting Behavior"(PDF).Paleobiology.30(2): 253–267.Bibcode:2004Pbio...30..253G.doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0253:chopom>2.0.co;2.JSTOR4096846.S2CID84961066.

- ^Galton, P. M. (1971). "A Primitive Dome-Headed Dinosaur (Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of England and the Function of the Dome of Pachycephalosaurids".Journal of Paleontology.45(1): 40–47.JSTOR1302750.

- ^Sues, H. D. (1978). "Functional morphology of the dome in pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs".Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Monatshefte.8:459–472.

- ^Snively, E.; Cox, A. (2008)."Structural Mechanics of Pachycephalosaur Crania Permitted Head-butting Behavior".Palaeontologia Electronica.11:1–17.

- ^Snively, E.; Theodor, J. M. (2011)."Common Functional Correlates of Head-Strike Behavior in the Pachycephalosaur Stegoceras validum (Ornithischia, Dinosauria) and Combative Artiodactyls".PLOS ONE.6(6): e21422.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621422S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021422.PMC3125168.PMID21738658.

- ^Moore, Bryan R. S.; Roloson, Mathew J.; Currie, Philip J.; Ryan, Michael J.; Patterson, R. Timothy; Mallon, Jordan C. (2022)."The appendicular myology ofStegoceras validum(Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae) and implications for the head-butting hypothesis ".PLOS ONE.17(9): e0268144.Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1768144M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268144.PMC9436104.PMID36048811.

- ^Padian, K.; Horner, J. R. (2011). "The evolution of 'bizarre structures' in dinosaurs: biomechanics, sexual selection, social selection or species recognition?".Journal of Zoology.283(1): 3–17.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00719.x.

- ^Knell, R. J.; Sampson, S. (January 2011)."Bizarre structures in dinosaurs: species recognition or sexual selection? A response to Padian and Horner: Bizarre structures in dinosaurs".Journal of Zoology.283(1): 18–22.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00758.x.

- ^Hone, D. W. E.; Naish, D. (2013)."The 'species recognition hypothesis' does not explain the presence and evolution of exaggerated structures in non-avialan dinosaurs".Journal of Zoology.290(3): 172–180.doi:10.1111/jzo.12035.

- ^Horner, John R.; Goodwin, Mark B.; Evans, David C. (2023). "A new pachycephalosaurid from the Hell Creek Formation, Garfield County, Montana, U.S.A.".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.42(4).doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2190369.

- ^Mallon, J. C.; Evans, D. C. (2014). "Taphonomy and habitat preference of North American pachycephalosaurids (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)".Lethaia.47(4): 567–578.Bibcode:2014Letha..47..567M.doi:10.1111/let.12082.

- ^Eberth, David A. (2005)."The Geology".In Currie, Philip J.; Koppelhus, Eva Bundgaard (eds.).Dinosaur Provincial Park.Indiana University Press. pp.54–82.ISBN978-0-253-34595-0.

- ^Braman, Dennis R.; Koppelhus, Eva B. (2005)."Campanian palynomorphs".In Currie, Philip J.; Koppelhus, Eva Bundgaard (eds.).Dinosaur Provincial Park.Indiana University Press. pp.101–30.ISBN978-0-253-34595-0.

- ^Weishampel, D. B.; Barrett, P. M.; Coria, R. A.; Le Loeuff, J.; Xu Xing; Z. X.; Sahni, A.; Gomani M.P., Elizabeth; Noto, C. R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.).The Dinosauria(2nd ed.). University of California Press. pp.517–606.ISBN978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^Eberth, D. A. (1997). "Judith River Wedge". InCurrie, Philip J.;Padian, Kevin (eds.).Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs.San Diego: Academic Press. pp.199–204.ISBN978-0-12-226810-6.

External links

[edit] Media related toStegocerasat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toStegocerasat Wikimedia Commons Data related toStegocerasat Wikispecies

Data related toStegocerasat Wikispecies