Structuralism (biology)

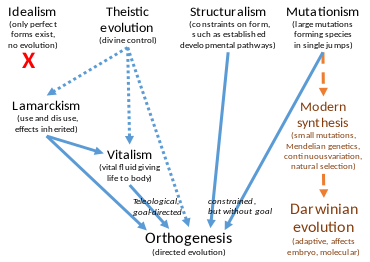

Biologicalorprocess structuralismis a school of biological thought that objects to an exclusivelyDarwinianoradaptationistexplanation ofnatural selectionsuch as is described in the20th century's modern synthesis.It proposes instead thatevolution is guided differently,basically by more or less physical forces which shape the development of an animal's body, and sometimes implies that these forces supersede selection altogether.

Structuralists have proposed different mechanisms that might have guided the formation ofbody plans.Before Darwin,Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaireargued that animals sharedhomologous parts,and that if one was enlarged, the others would be reduced in compensation. After Darwin,D'Arcy Thompsonhinted atvitalismand offered geometric explanations in his classic 1917 bookOn Growth and Form.Adolf Seilachersuggested mechanical inflation for "pneu" structures inEdiacaran biotafossils such asDickinsonia.Günter P. Wagnerargued for developmental bias, structural constraints onembryonic development.Stuart Kauffmanfavouredself-organisation,the idea that complex structure emergesholisticallyand spontaneously from the dynamic interaction of all parts of anorganism.Michael Dentonargued for laws of form by whichPlatonic universalsor "Types" are self-organised.Stephen J. GouldandRichard Lewontinproposedbiological "spandrels",features created as a byproduct of the adaptation of nearby structures.Gerd B. Müllerand Stuart A. Newman argued that the appearance in thefossil recordof most of the currentphylain theCambrian explosionwas "pre-Mendelian"[a]evolution caused by physical factors.Brian Goodwin,described by Wagner as part of "afringemovement in evolutionary biology ",[2]denies that biological complexity can bereducedto natural selection, and argues thatpattern formationis driven bymorphogenetic fields.

Darwinian biologists have criticised structuralism, emphasising that there is plentiful evidence both that natural selection is effective and, fromdeep homology,thatgeneshave been involved in shaping organisms throughoutevolutionary history.They accept that some structures such as thecell membraneself-assemble, but deny the ability of self-organisation to drive large-scale evolution.

History[edit]

Geoffroy's law of compensation[edit]

In 1830,Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaireargued a structuralist case against the functionalist (teleological) position ofGeorges Cuvier.Geoffroy believed thathomologiesof structure between animals indicated that they shared an ideal pattern; these did not imply evolution but a unity of plan, a law of nature.[b]He further believed that if one part was more developed within a structure, the other parts would necessarily be reduced in compensation, as nature always used the same materials: if more of them were used for one feature, less was available for the others.[4]

D'Arcy Thompson's morphology[edit]

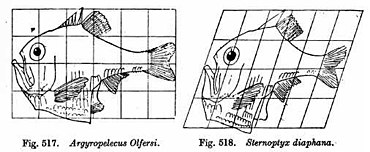

In his "eccentric, beautiful"[5]1917 bookOn Growth and Form,D'Arcy Wentworth Thompsonrevisited the old idea of "universal laws of form"to explain the observed forms of living organisms.[1]The science writerPhilip Ballstates that Thompson "presents mathematical principles as a shaping agency that may supersede natural selection, showing how the structures of the living world often echo those in inorganic nature", and notes his "frustration at the 'Just So' explanations ofmorphologyoffered by Darwinians. "Instead, Ball writes, Thompson elaborates on how not heredity but physical forces govern biological form.[6]Thephilosopher of biologyMichael Rusesimilarly wrote that Thompson "had little time for natural selection", certainly preferring "mechanical explanations" and possibly straying intovitalism.[1]

Seilacher's pneu structures[edit]

Like Thompson, the palaeontologistAdolf Seilacheremphasised fabricational constraints on form. He interpreted fossils such asDickinsoniain theEdiacaran biotaas "pneu" structures determined by mechanical inflation like a quiltedair mattress,rather than having been driven by natural selection.[7][8]

Wagner's constraints on development[edit]

In his 2014 bookHomology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation,the evolutionary biologistGünter P. Wagnerargues for "the study of novelty as distinct from adaptation." He defines novelty as occurring when some part of the body develops an individual and quasi-independent existence, in other words as a distinct and recognisable structure, which he implies might occur before natural selection begins to adapt the structure for some function.[2][9]He forms a structuralist picture ofevolutionary developmental biology,using empirical evidence, arguing thathomologyand biological novelty are key aspects requiring explanation, and that developmental bias (i.e. structural constraints on embryonic development) is a key explanation for these.[10][11]

Kauffman's self-organisation[edit]

The mathematical biologistStuart Kauffmansuggested in 1993 thatself-organizationmay play a role alongsidenatural selectionin three areas ofevolutionary biology,namelypopulation dynamics,molecular evolution,andmorphogenesis.With respect to molecular biology, Kauffman has been criticised for ignoring the role ofenergyin drivingbiochemical reactionsin cells, which can fairly be called self-catalysingbut which do not simply self-organise.[12]

Denton's 'Types'[edit]

The biochemistMichael Dentonhas argued a structuralist case for self-organization. In a 2013 paper, he claimed that "the basic forms of the natural world—the Types—are immanent in nature, and determined by a set of special natural biological laws, the so called 'laws of form'." He asserts that these "recurring patterns and forms" are "genuineuniversals".[c]Form is in this view not shaped by natural selection, but by "self-organizing properties of particular categories of matter" and by "cosmic fine-tuning of the laws of nature".[14]Denton has been criticised by the biochemist Laurence A. Moran as anti-Darwinian and favouringcreationism.[15]

Gould and Lewontin's spandrels[edit]

In 1979, influenced by Seilacher among others, thepaleontologistStephen J. Gouldand thepopulation geneticistRichard Lewontinwrote what Wagner called "the most influential structuralist manifesto", "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm".[16][2]They pointed out that biological features (likearchitectural spandrels) did not necessarily haveadaptationas their direct cause. Instead, architects couldn't help creating small triangular areas betweenarchesandpillars,as arches need (evolve) to be curved, and pillars need to be vertical. The resulting spandrels areexaptations,consequences of other evolutionary changes. Evolution, they argued, did not select for a protruding human chin: instead, reducing the length of the tooth row left the jaw protruding.[2]

Müller and Newman's pre-Mendelian evolution[edit]

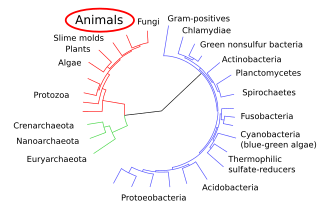

Extreme structuralists likeGerd B. Müllerand Stuart A. Newman, inheriting the viewpoint of D'Arcy Thompson, have proposed that physical laws of structure, notgenetics,govern major diversifications such as theCambrian explosion,followed later by co-opted genetic mechanisms.[17][18]They argued further that there was a "pre-Mendelian" phase of the evolution of animals, involving physical forces, before genes took over.[17][19]Darwinian biologists freely admit that physical factors such as surface tension can causeself-assembly,but insist thatgenesplay a crucial role. They note for example thatdeep homologiesbetween widely separated groups of organisms, such as thesignalling pathwaysandtranscription factorsofchoanoflagellatesandmetazoans,demonstrate that genes have been involved throughoutevolutionary history.[20]

Goodwin's morphogenetic fields[edit]

What Wagner calls "a fringe movement in evolutionary biology",[2]the form of structuralism exemplified byBrian Goodwin,[2][21]effectively denies that natural selection is important,[2][22]or at least that biological complexity could bereducedto natural selection.[22][23]This led to conflict with Darwinists such asRichard Dawkins.[24]Goodwin related the old concept of amorphogenetic fieldto the spatial distribution of chemical signals in a developing embryo.[25]He demonstrated with a mathematical model that a variety ofpatterns could be formedby choosing parameter values to set up either static geometric patterns or dynamic oscillations,[22][23]implying that the signalling system involved was somehow an alternative to natural selection.[15]Dawkins commented "He thinks he's anti-Darwinian, although he can't be, because he has no alternative explanation."[26]

Criticism[edit]

While agreeing that pattern formation mechanisms such as those described by Goodwin exist, the biologists Richard Dawkins, Stephen J. Gould,Lynn Margulis,andSteve Joneshave criticised Goodwin for suggesting that chemical signalling forms an alternative to natural selection.[15]

Moran, a "skeptical biochemist", comments that 'structuralism' is a "new buzzword... guaranteed to impress the creationist crowd because nobody understands what it means but it sounds very 'sciency' and philosophical."[15]The philosopher of sciencePaul E. Griffithswrites that structuralists "view this structuring of the space of biological possibility as part of the fundamental physical structure of nature. But the phenomena of phylogenetic inertia and developmental constraint do not support this interpretation. These phenomena show that the evolutionary pathways available to an organism are a function of the developmental structure of the organism."[27]

Moran summarizes: "There's nothing in science that supports the views of the structuralists. We have perfectly good explanations for why bumblebees are different than mushrooms and why all vertebrates have vertebrae and not exoskeletons. There's no evidence to support the idea that if you replay the tape of life it will come out looking anything like what we see today. You can be confident that when you visit another planet you will not find vertebrates."[15]

Theevolutionary developmental biologistLewis Heldwrote that "The notion that aspects of anatomy can be explained by physical forces (like expansion cracking) was advocated ~ 100 years earlier in D'Arcy Thompson's 1917On Growth and Formand inTheodore Cook's 1914 bookThe Curves of Life.[d]Over the intervening century, various traits have been proposed to arisemechanicallyrather thangenetically:brain convolutions, cartilage condensations, flower corrugations, tooth cusps, and fish otoliths. To this kooky list we can now add the crooked smile of the crocodile, or at least the cracked skin that surrounds it. "[e][28]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Gregor Mendelpioneered the study ofgenetics.

- ^In this, Geoffroy's homologies were likeAristotle's forms.

- ^Universals are central to theancient Greektheory,Platonic realism.[13]

- ^The artist Theodore Cook'sThe Curves of Life,Constable, 1914 to some extent anticipated D'Arcy Thompson, exploringspiralsin art and nature.

- ^Held's final point was that the cracks in the crocodile's skin are genuinely explained by cracking, unlike all the other examples he lists.[28]

References[edit]

- ^abcRuse, Michael (2013)."17. From Organicism to Mechanism-and Halfway Back?".In Henning, Brian G.; Scarfe, Adam (eds.).Beyond Mechanism: Putting Life Back Into Biology.Le xing ton Books. p. 419.ISBN9780739174371.

- ^abcdefgWagner, Günter P.,Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation.Princeton University Press. 2014.ISBN978-0691156460.Pages 7–38, 125

- ^Bowler, Peter J.(1989) [1983].The Eclipse of Darwinism: anti-Darwinian evolutionary theories in the decades around 1900.Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 261–262, 280–281.ISBN978-0-8018-4391-4.

- ^Racine, Valerie (7 October 2013)."Essay: The Cuvier-Geoffroy Debate".The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University.Retrieved10 December2016.

- ^Leroi, Armand Marie(2014).The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science.Bloomsbury. p. 13.ISBN978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^Ball, Philip (7 February 2013)."In retrospect: On Growth and Form".Nature.494(7435): 32–33.Bibcode:2013Natur.494...32B.doi:10.1038/494032a.S2CID205076253.

- ^Seilacher, Adolf (1991). "Self-Organizing Mechanisms in Morphogenesis and Evolution". In Schmidt-Kittler, Norbert; Vogel, Klaus (eds.).Constructional Morphology and Evolution.Springer. pp. 251–271.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-76156-0_17.ISBN978-3-642-76158-4.

- ^Seilacher, Adolf(July 1989). "Vendozoa: Organismic construction in the Proterozoic biosphere".Lethaia.22(3): 229–239.doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1989.tb01332.x.

- ^Simpson, Carl; Erwin, Douglas H. (quoted) (13 April 2014).Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation Günter P. Wagner.Princeton University Press.ISBN9780691156460.Retrieved9 December2016.

- ^Brown, Rachael L. (November 2015). "Why development matters".Biology & Philosophy.30(6): 889–899.doi:10.1007/s10539-015-9488-9.S2CID82602032.

- ^Muller, G. B.; Wagner, G. P. (1991)."Novelty in Evolution: Restructuring the Concept"(PDF).Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics.22(1): 229–256.doi:10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.001305.ISSN0066-4162.Archived(PDF)from the original on 26 September 2017.

- ^Fox, Ronald F. (December 1993)."Review of Stuart Kauffman, The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution".Biophys. J.65(6): 2698–2699.Bibcode:1993BpJ....65.2698F.doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(93)81321-3.PMC1226010.

- ^Silverman, Allan."Plato's Middle Period Metaphysics and Epistemology".InZalta, Edward N.(ed.).Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^Denton, Michael J. (August 2013)."The Types: A Persistent Structuralist Challenge to Darwinian Pan-Selectionism".BIO-Complexity.2013(3).doi:10.5048/BIO-C.2013.3.

- ^abcdefMoran, Laurence A. (2016-02-02)."What is" Structuralism "?".Sandwalk (blog of a recognised expert).Retrieved9 December2016.

- ^Stephen Jay Gould;Richard Lewontin(1979). "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme".Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B.205(1161): 581–598.Bibcode:1979RSPSB.205..581G.doi:10.1098/rspb.1979.0086.PMID42062.S2CID2129408.

- ^abErwin, Douglas H.(September 2011)."Evolutionary uniformitarianism".Developmental Biology.357(1): 27–34.doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.020.PMID21276788.

- ^Müller, Gerd B.;Newman, Stuart A. (2005). "The innovation triad: an EvoDevo agenda".J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev Evol).304B(6): 487–503.CiteSeerX10.1.1.501.1440.doi:10.1002/jez.b.21081.PMID16299770.

- ^Newman, Stuart A.; Forgacs, Gabor;Müller, Gerd B.(2006)."Before programs: The physical origination of multicellular forms".The International Journal of Developmental Biology.50(2–3): 289–299.doi:10.1387/ijdb.052049sn.PMID16479496.

- ^King, Nicole (2004)."The Unicellular Ancestry of Animal Development".Developmental Cell.7(3): 313–325.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.010.PMID15363407.

- ^Goodwin, Brian(2009).Ruse, Michael;Travis, Joseph (eds.).Beyond the Darwinian Paradigm: Understanding Biological Forms.Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0674062214.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^abcPrice, Catherine S. C.; Goodwin, Brian (1995). "Structurally Unsound".Evolution.49(6): 1298.doi:10.2307/2410461.JSTOR2410461.

- ^abWake, David B.(1996). "How the Leopard Changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity by Brian Goodwin".American Scientist.84(3): 300–301.JSTOR29775684.

- ^Brian Goodwin obituary -The Guardian,9 August 2009

- ^Dickinson, W. Joseph (1998). "Form and Transformation: Generative and Relational Principles in Biology. by Gerry Webster; Brian Goodwin".The Quarterly Review of Biology.73(1): 62–63.doi:10.1086/420070.

- ^Dawkins, Richard(1 May 1996)."Chapter 3" A Survival Machine "".Edge.Retrieved11 February2018.

- ^Griffiths, Paul E.(1996). "Darwinism, Process Structuralism, and Natural Kinds".Philosophy of Science.63(5): S1–S9.doi:10.1086/289930.JSTOR188505.S2CID146674266.

- ^abHeld, Lewis Irving (2014).How the snake lost its legs: curious tales from the frontier of evo-devo.Cambridge, United Kingdom New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 121.ISBN978-1-107-62139-8.