Sumo

A sumo match (tori-kumi) betweenyokozunaAsashōryū(left) andkomusubiKotoshōgikuin January 2008 | |

| Focus | Clinch fighting |

|---|---|

| Hardness | Full contact |

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Ancestor arts | Tegoi |

| Descendant arts | Jujutsu,Jieitaikakutōjutsu |

| Olympic sport | No, butIOCrecognized |

| Official website | www |

| Highestgoverning body | International Sumo Federation(Amateur) Japan Sumo Association(Professional) |

|---|---|

| First played | Japan, mid-17th century (Edo period) |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Team members | No |

| Mixed-sex | Yes (Amateur, separate divisions) No (Professional, men only) |

| Type | Grappling sport |

| Equipment | Mawashi |

| Venue | Dohyō |

| Glossary | Glossary of sumo terms |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide (Amateur) Japan (Professional) |

| Olympic | No |

| Paralympic | No |

| World Games | 2001(invitational) 2005–Present |

| Sumo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Sumo" inkanji | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | Đô vật | ||||

| |||||

Sumo(Japanese:Đô vật,Hepburn:sumō,Japanese pronunciation:[ˈsɯmoː],lit. 'striking one another')[1]is a form of competitive full-contactwrestlingwhere arikishi(wrestler) attempts to force his opponent out of a circular ring (dohyō) or into touching the ground with any body part other than the soles of his feet (usually by throwing, shoving or pushing him down).

Sumo originated inJapan,the only country where it is practiced professionally and where it is considered thenational sport.[2][3]It is considered agendai budō,which refers to modernJapanese martial arts,but the sport has a history spanning many centuries. Many ancient traditions have been preserved in sumo, and even today the sport includes many ritual elements, such as the use of salt purification, fromShinto.

Life as a wrestler is highly regimented, with rules regulated by theJapan Sumo Association.Most sumo wrestlers are required to live in communal sumo training stables, known in Japanese asheya,where all aspects of their daily lives—from meals to their manner of dress—are dictated by strict kyara tradition. The lifestyle has a negative effect on their health, with sumo wrestlers having a much lower life expectancy than the average Japanese man.

From 2008 to 2016, a number of high-profilecontroversies and scandalsrocked the sumo world, with an associated effect on its reputation and ticket sales. These have also affected the sport's ability to attract recruits.[4]Despite this setback, sumo's popularity and general attendance has rebounded due to having multipleyokozuna(or grand champions) for the first time in a number of years and other high-profile wrestlers grabbing the public's attention.[5]

Etymology[edit]

The spoken wordsumōgoes back to the verbsumau/sumafu,meaning 'compete' or 'fight'. The written word goes back to the expressionsumai no sechi(Đô vật の tiết),which was a wrestling competition at the imperial court during theHeian period.The characters fromsumai,orsumōtoday, mean 'to strike each other'. There are instances of "sumo" alternatively being written with thekanji"Đấu sức",as in theNihon Shoki.Here, the first character means 'corner', but serves as a phonetic element as one reading of it issumi,while the second character means 'force'.

Sumōis also a general term for wrestling in Japanese. For example,udezumō(Cổ tay đô vật,'arm sumō')means 'arm wrestling', andyubizumō(Chỉ đô vật,'finger sumō')means 'finger wrestling'. The professional sumo observed by theJapan Sumo Associationis calledōzumō(Đại đô vật),or 'grand sumo'.

History[edit]

Antiquity (pre-1185)[edit]

Prehistoric wall paintings indicate that sumo originated from an agriculturalritual danceperformed in prayer for a good harvest.[6]The first mention of sumo can be found in aKojikimanuscript dating back to 712, which describes how possession of the Japanese islands was decided in a wrestling match between thekamiknown asTakemikazuchiandTakeminakata.

Takemikazuchi was a god of thunder, swordsmanship, and conquest, created from the blood that was shed whenIzanagislew the fire-demonKagu-tsuchi.Takeminakata was a god of water, wind, agriculture and hunting, and a distant descendant of the storm-godSusanoo.When Takemikazuchi sought to conquer the land ofIzumo,Takeminakata challenged him in hand-to-hand combat. In their melee, Takemikazuchi grappled Takeminakata's arm and crushed it "like a reed", defeating Takeminakata and claiming Izumo.[7][8]

TheNihon Shoki,published in 720, dates the first sumo match between mortals to the year 23 BC, when a man namedNomi no Sukunefought against Taima no Kuehaya at the request ofEmperor Suininand eventually killed him, making him the mythological ancestor of sumo.[6][9]According to theNihon Shoki,Nomi broke a rib of Taima with one kick, and killed him with a kick to the back as well.[7]Until the Japanese Middle Ages, this unregulated form of wrestling was often fought to the death of one of the fighters.[6]In theKofun period(300–538),Haniwaof sumo wrestlers were made.[10]The first historically attested sumo fights were held in 642 at the court ofEmpress Kōgyokuto entertain a Korean legation. In the centuries that followed, the popularity of sumo within the court increased its ceremonial and religious significance. Regular events at the Emperor's court, thesumai no sechie,and the establishment of the first set of rules for sumo fall into the cultural heyday of theHeian period.

Japanese Middle Ages (1185–1603)[edit]

With the collapse of the Emperor's central authority, sumo lost its importance in the court; during theKamakura period,sumo was repurposed from a ceremonial struggle to a form of military combat training amongsamurai.[6][9]By theMuromachi period,sumo had fully left the seclusion of the court and became a popular event for the masses, and among thedaimyōit became common to sponsor wrestlers.Sumotoriwho successfully fought for adaimyō's favor were given generous support andsamuraistatus.Oda Nobunaga,a particularly avid fan of the sport, held a tournament of 1,500 wrestlers in February 1578. Because several bouts were to be held simultaneously within Oda Nobunaga's castle, circular arenas were delimited to hasten the proceedings and to maintain the safety of the spectators. This event marks the invention of thedohyō,which would be developed into its current form up until the 18th century.[6]The winner of Nobunaga's tournament was given a bow for being victorious and he began dancing to show the war-lord his gratitude.[7]

Edo period (1603–1867)[edit]

Because sumo had become a nuisance due to wild fighting on the streets, particularly in Edo, sumo was temporarily banned in the city during theEdo period.In 1684, sumo was permitted to be held for charity events on the property of Shinto shrines, as was common inKyotoandOsaka.The first sanctioned tournament took place in theTomioka Hachiman Shrineat this time. An official sumo organization was developed, consisting of professional wrestlers at the disposal of the Edo administration. Many elements date from this period, such as thedohyō-iri,theheyasystem, thegyōjiand themawashi.The 18th century brought forth several notable wrestlers such asRaiden Tameemon,Onogawa KisaburōandTanikaze Kajinosuke,the first historicalyokozuna.

WhenMatthew Perrywas shown sumo wrestling during his 1853 expedition to Japan, he found it distasteful and arranged a military showcase to display the merits of Western organization.[11]

Since 1868[edit]

TheMeiji Restorationof 1868 brought about the end of the feudal system, and with it the wealthydaimyōas sponsors. Due to a new fixation onWestern culture,sumo had come to be seen as an embarrassing and backward relic, and internal disputes split the central association. The popularity of sumo was restored whenEmperor Meijiorganized a tournament in 1884; his example would make sumo a national symbol and contribute to nationalist sentiment following military successes against Korea and China. The Japan Sumo Association reunited on 28 December 1925 and increased the number of annual tournaments from two to four, and then to six in 1958. The length of tournaments was extended from ten to fifteen days in 1949.[7]

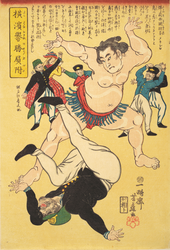

- Gallery

-

Kanjin Grand Sumo Tournament (c. 1843)

-

Sumo wrestling scenec. 1851

-

Somagahana Fuchiemon,c. 1850

-

American sailors of thePerry Expeditionexamining a sumo wrestler (1854)

Rules and customs[edit]

The elementary principle of sumo is that a match is decided by a fighter first either being forced out of the circulardohyō(ring) (not necessarily having to touch the ground outside the ring with any part of the body), or touching the ground inside the ring with any part of the body other than the soles of the feet. The wrestlers try to achieve this by pushing, tossing, striking and often by outwitting the opponent.[12]TheJapan Sumo Associationcurrently distinguishes 82kimarite(winning techniques), some of which come fromjudo.[13]Illegal moves are calledkinjite,which include strangulation, hair-pulling, bending fingers, gripping the crotch area, kicking, poking eyes, punching and simultaneously striking both the opponent's ears. The most common basic forms are grabbing the opponent by themawashi(belt) and then forcing him out, a style calledyotsu-zumō(Bốn つ đô vật),or pushing the opponent out of the ring without a firm grip, a style calledoshi-zumō(Áp し đô vật).

Thedohyō,which is constructed and maintained by theyobidashi,consists of a raised pedestal on which a circle 4.55 m (14.9 ft) in diameter is delimited by a series of rice-straw bales. In the middle of the circle there are two starting lines (shikiri-sen), behind which the wrestlers line up for thetachi-ai,the synchronized charge that initiates the match.[14][15]The direction of the match is incumbent on thegyōji,a referee who is supported by fiveshimpan(judges). In some situations, a review of thegyōji's decision may be needed. Theshimpanmay convene a conference in the middle of the ring, called amono-ii.This is done if the judges decide that the decision over who won the bout needs to be reviewed; for example, if both wrestlers appear to touch the ground or step out of the ring at the same time. In these cases, sometimes video is reviewed to see what happened. Once a decision is made, the chief judge will announce the decision to the spectators and the wrestlers alike. They may order a bout to be restarted, or leave the decision as given by thegyōji.Occasionally theshimpanwill overrule thegyōjiand give the bout to the other wrestler. On rare occasions the referee or judges may award the win to the wrestler who touched the ground first. This happens if both wrestlers touch the ground at nearly the same time and it is decided that the wrestler who touched the ground second had no chance of winning, his opponent's superiorsumohaving put him in an irrecoverable position. The losing wrestler is referred to as beingshini-tai( "dead body" ) in this case.[16]

The maximum length of a match varies depending on the division. In the top division, the limit is four minutes, although matches usually only last a few seconds. If the match has not yet ended after the allotted time has elapsed, amizu-iri(water break) is taken, after which the wrestlers continue the fight from their previous positions. If a winner is still not found after another four minutes, the fight restarts from thetachi-aiafter anothermizu-iri.If this still does not result in a decision, the outcome is considered ahikiwake(draw). This is an extremely rare result, with the last such draw being called in September 1974.[17]

A special attraction of sumo is the variety of observed ceremonies and rituals, some of which have been cultivated in connection with the sport and unchanged for centuries. These include the ring-entering ceremonies (dohyō-iri) at the beginning of each tournament day, in which the wrestlers appear in the ring in elaboratekesho-mawashi,but also such details as the tossing of salt into the ring by the wrestlers, which serves as a symbolic cleansing of the ring,[16]and rinsing the mouth withchikara-mizu(Lực thủy,power water)before a fight, which is similar to the ritual before entering a Shinto shrine. Additionally, before a match begins the two wrestlers perform and repeat a warm up routine calledshikiri.The top division is given four minutes forshikiri,while the second division is given three, after which the timekeeping judge signals to thegyōjithat time is up.[16]

Traditionally, sumo wrestlers are renowned for their great girth and body mass, which is often a winning factor in sumo. No weight divisions are used in professional sumo; a wrestler can sometimes face an opponent twice his own weight. However, with superior technique, smaller wrestlers can control and defeat much larger opponents.[18]The average weight of top division wrestlers has continued to increase, from 125 kilograms (276 lb) in 1969 to over 150 kilograms (330 lb) by 1991, and was a record 166 kilograms (366 lb) as of January 2019.[19]

Professional sumo[edit]

Professional sumo is organized by theJapan Sumo Association.[17]The members of the association, calledoyakata,are all former wrestlers, and are the only people entitled to train new wrestlers. All professional wrestlers must be a member of a training stable (orheya) run by one of theoyakata,who is the stablemaster for the wrestlers under him. In 2007, 43 training stables hosted 660 wrestlers.[20]

To turn professional, wrestlers must have completed at least nine years ofcompulsory educationand meet minimum height and weight requirements.[16]In 1994, the Japanese Sumo Association required that all sumo wrestlers be a minimum 173 cm (5 ft 8 in) in height. This prompted 16-year-old Takeji Harada of Japan (who had failed six previous eligibility tests) to have four separate cosmetic surgeries over a period of 12 months to add an extra 15 cm (6 in) of silicone to his scalp, which created a large, protruding bulge on his head.[21]In response to this, the JSA stated that they would no longer accept aspiring wrestlers who surgically enhanced their height, citing health concerns.[22]In 2019,The Japan Timesreported that the height requirement was 167 cm (5 ft 6 in), and the weight requirement was 67 kg (148 lb), although they also claimed that a "blind eye" is turned for those "just shy" of the minimums.[23]In 2023 the Sumo Association loosened the height and weight requirements, announcing that prospective recruits not meeting the minimums could still enter sumo by passing aphysical fitness exam.[24]

All sumo wrestlers take wrestling names calledshikona(Bốn cổ danh),which may or may not be related to their real names. Often, wrestlers have little choice in their names, which are given to them by their stablemasters, or by a supporter or family member who encouraged them into the sport. This is particularly true of foreign-born wrestlers. A wrestler may change his wrestling name during his career, with some changing theirs several times.[17]

Professional sumo wrestling has a strict hierarchy based on sporting merit. The wrestlers are ranked according to a system that dates back to the Edo period. They are promoted or demoted according to their performance in six official tournaments held throughout the year, which are calledhonbasho.A carefully preparedbanzukelisting the full hierarchy is published two weeks prior to each sumo tournament.[25]

In addition to the professional tournaments, exhibition competitions are held at regular intervals every year in Japan, and roughly once every two years, the top-ranked wrestlers visit a foreign country for such exhibitions. None of these displays are taken into account in determining a wrestler's future rank. Rank is determined only by performance in grand sumo tournaments.[14]

Sumo divisions[edit]

The six divisions in sumo, in descending order of prestige, are:

- makuuchi(Mạc nội)ormakunouchi(Mạc の nội).[16]Maximum 42 wrestlers; Further divided into five ranks

- jūryō(Mười lạng).Fixed at 28 wrestlers

- makushita(Mạc hạ).Fixed at 120 wrestlers

- sandanme(Tam đoạn mục).Fixed at 180 wrestlers

- jonidan(Tự nhị đoạn).About 200 wrestlers

- jonokuchi(Tự ノ khẩu or tự の khẩu).Around 50 wrestlers

Wrestlers enter sumo in the lowestjonokuchidivision and, ability permitting, work their way up to the top division. A broad demarcation in the sumo world can be seen between the wrestlers in the top two divisions known assekitori(Quan lấy)and those in the four lower divisions, known commonly by the more generic termrikishi(Lực sĩ).The ranks receive different levels of compensation, privileges, and status.[26]

The topmostmakuuchidivision receives the most attention from fans and has the most complex hierarchy. The majority of wrestlers aremaegashira(Đằng trước)and are ranked from the highest level 1 down to about 16 or 17. In each rank are two wrestlers, the higher rank is designated as "east" and the lower as "west", so the list goes #1 east, #1 west, #2 east, #2 west, etc.[27]Above themaegashiraare the three champion or titleholder ranks, called thesan'yaku,which are only numbered if the number of wrestlers in each rank exceeds two. These are, in ascending order,komusubi(Tiểu kết),sekiwake(Quan hiếp),andōzeki(Đại quan).At the pinnacle of the ranking system is the rank ofyokozuna(Hoành cương).[26]

Yokozuna,or grand champions, are generally expected to compete for and to win the top division tournament title on a regular basis, hence the promotion criteria foryokozunaare very strict. In general, anōzekimust win the championship for two consecutive tournaments or an "equivalent performance" to be considered for promotion toyokozuna.[17]More than one wrestler can hold the rank ofyokozunaat the same time.

In antiquity, sumo was solely a Japanese sport. Since the 1900s, however, the number of foreign-born sumo wrestlers has gradually increased. In the beginning of this period, these few foreign wrestlers were listed as Japanese, but particularly since the 1960s, a number of high-profileforeign-born wrestlersbecame well-known, and in more recent years have even come to dominate in the highest ranks. In the 10 years since January 2009, five of the nine wrestlers promoted toōzekihave been foreign-born,[28]and a Japanese had not been namedyokozunafrom 1998 until the promotion ofKisenosato Yutakain 2017. This and other issues eventually led the Sumo Association to limit the number of foreigners allowed to one in each stable.

Women and sumo[edit]

Women are not allowed to compete in professional sumo. They are also not allowed to enter the wrestling ring (dohyō), a tradition stemming from Shinto and Buddhist beliefs thatwomen are "impure" because of menstrual blood.[29][30][31]

A form of female sumo(Nữ đô vật,onnazumo)existed in some parts of Japan before professional sumo was established.[32]The 2018 filmThe Chrysanthemum and the Guillotinedepicts female sumo wrestlers at the time of civil unrest following the1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

Professional sumo tournaments[edit]

Since 1958, six Grand Sumo tournaments orhonbashohave been held each year: three at theKokugikanin Tokyo (January, May, and September), and one each inOsaka(March),Nagoya(July), andFukuoka(November). Until the end of 1984, the Kokugikan was located inKuramae,Tokyo, but moved in 1985 to the newly built venue atRyōgoku.[33]Each tournament begins on a Sunday and runs for 15 days, ending also on a Sunday, roughly in the middle of the month.[16][34]The tournaments are organized in a manner akin to aMcMahon system tournament;each wrestler in the top two divisions (sekitori) has one match per day, while the lower-ranked wrestlers compete in seven bouts, about one every two days.

Each day is structured so that the highest-ranked contestants compete at the end of the day. Thus, wrestling starts in the morning with thejonokuchiwrestlers and ends at around six o'clock in the evening with bouts involving theyokozuna.The wrestler who wins the most matches over the 15 days wins the tournament championship (yūshō) for his division. If two wrestlers are tied for the top, they wrestle each other and the winner takes the title. Three-way ties for a championship are rare, at least in the top division. In these cases, the three wrestle each other in pairs with the first to win two in a row take the tournament. More complex systems for championship playoffs involving four or more wrestlers also exist, but these are usually only seen in determining the winner of one of the lower divisions.

The matchups for each day of the tournament are determined by the sumo elders who are members of the judging division of theJapan Sumo Association.They meet every morning at 11 am and announce the following day's matchups around 12 pm. An exception are the final day 15 matchups, which are announced much later on day 14.[16]Each wrestler only competes against a selection of opponents from the same division, though small overlaps can occur between two divisions. The first bouts of a tournament tend to be between wrestlers who are within a few ranks of each other.[16]Afterwards, the selection of opponents takes into account a wrestler's prior performance. For example, in the lower divisions, wrestlers with the same record in a tournament are generally matched up with each other and the last matchups often involve undefeated wrestlers competing against each other, even if they are from opposite ends of the division. In the top division, in the last few days, wrestlers with exceptional records often have matches against much more highly ranked opponents, includingsan'yakuwrestlers, especially if they are still in the running for the top division championship. Similarly, more highly ranked wrestlers with very poor records may find themselves fighting wrestlers much further down the division.

For theyokozunaandōzeki,the first week and a half of the tournament tends to be taken up with bouts against the topmaegashira,komusubi,andsekiwake,with the bouts within these ranks being concentrated into the last five days or so of the tournament (depending on the number of top-ranked wrestlers competing). Traditionally, on the final day, the last three bouts of the tournament are between the top six ranked wrestlers, with the top two competing in the final matchup, unless injuries during the tournament prevent this.

Certain match-ups are prohibited in regular tournament play. Wrestlers who are from the same training stable cannot compete against each other, nor can wrestlers who are brothers, even if they join different stables. The one exception to this rule is that training stable partners and brothers can face each other in a championship-deciding playoff match.

The last day of the tournament is calledsenshūraku,which literally means "the pleasure of a thousand autumns". This colorful name for the culmination of the tournament echoes the words of the playwrightZeamito represent the excitement of the decisive bouts and the celebration of the victor. The Emperor's Cup is presented to the wrestler who wins the top-divisionmakuuchichampionship. Numerous other (mostly sponsored) prizes are also awarded to him. These prizes are often rather elaborate, ornate gifts, such as giant cups, decorative plates, and statuettes. Others are quite commercial, such as one trophy shaped like a giant Coca-Cola bottle.

Promotion and relegation for the next tournament are determined by a wrestler's score over the 15 days. In the top division, the termkachikoshimeans a score of 8–7 or better, as opposed tomakekoshi,which indicates a score of 7–8 or worse. A wrestler who achieveskachikoshialmost always is promoted further up the ladder, the level of promotion being higher for better scores.[16]See themakuuchiarticle for more details on promotion and relegation.

A top-division wrestler who is not anōzekioryokozunaand who finishes the tournament withkachikoshiis also eligible to be considered for one of the three prizes awarded for "technique", "fighting spirit", and defeating the mostyokozunaandōzekithe "outstanding performance" prize. For more information seesanshō.

For the list of upper divisions champions since 1909, refer to thelist of top division championsandthe list of second division champions.

A professional sumo bout[edit]

At the initial charge, both wrestlers must jump up from thecrouchsimultaneously after touching the surface of the ring with two fists at the start of the bout. The referee (gyōji) can restart the bout if this simultaneous touch does not occur.[16]

Upon completion of the bout, the referee must immediately designate his decision by pointing hisgunbaior war-fan towards the winning side. The winning technique (kimarite) used by the winner would then be announced to the audience. The wrestlers then return to their starting positions and bow to each other before retiring.

The referee's decision is not final and may be disputed by the fivejudgesseated around the ring. If this happens, they meet in the center of the ring to hold amono-ii(a talk about things). After reaching a consensus, they can uphold or reverse the referee's decision or order a rematch, known as atorinaoshi.

A winning wrestler in the top division may receive additional prize money in envelopes from the referee if the matchup has been sponsored. If ayokozunais defeated by a lower-ranked wrestler, it is common and expected for audience members to throw their seat cushions into the ring (and onto the wrestlers), though this practice is technically prohibited.

In contrast to the time in bout preparation, bouts are typically very short, usually less than a minute (most of the time only a few seconds). Extremely rarely, a bout can go on for several minutes.

Life as a professional sumo wrestler[edit]

A professional sumo wrestler leads a highly regimented way of life. The Sumo Association prescribes the behavior of its wrestlers in some detail. For example, the association prohibits wrestlers from driving cars, although this is partly out of necessity as many wrestlers are too big to fit behind a steering wheel.[35]Breaking the rules can result in fines and/or suspension for both the offending wrestler and his stablemaster.

On entering sumo, they are expected to grow their hair long to form a topknot, orchonmage,similar to thesamuraihairstyles of the Edo period. Furthermore, they are expected to wear thechonmageand traditional Japanese dress when in public, allowing them to be identified immediately as wrestlers.

The type and quality of the dress depends on the wrestler's rank.Rikishiinjonidanand below are allowed to wear only a thin cotton robe called ayukata,even in winter. Furthermore, when outside, they must wear a form of wooden sandal calledgeta.Wrestlers in themakushitaandsandanmedivisions can wear a form of traditional short overcoat over theiryukataand are allowed to wear straw sandals, calledzōri.The higher-rankedsekitorican wear silk robes of their own choice, and the quality of the garb is significantly improved. They also are expected to wear a more elaborate form of topknot called anōichō(bigginkgoleaf) on formal occasions.

Similar distinctions are made in stable life. The junior wrestlers must get up earliest, around 5 am, for training, whereas thesekitorimay start around 7 am. When thesekitoriare training, the junior wrestlers may have chores to do, such as assisting in cooking lunch, cleaning, and preparing baths, holding asekitori's towel, or wiping the sweat from him. The ranking hierarchy is preserved for the order of precedence in bathing after training, and in eating lunch.

Wrestlers are not normally allowed to eat breakfast and are expected to have asiesta-like nap after a large lunch.[16]The most common type of lunch served is the traditional sumo meal ofchankonabe,which consists of a simmering stew of various meat and vegetables cooked at the table, and usually eaten with rice.[16]This regimen of no breakfast and a large lunch followed by a sleep is intended to help wrestlers put on a lot of weight so as to compete more effectively. Sumo wrestlers also drink large amounts of beer.[36]

In the afternoon, the junior wrestlers again usually have cleaning or other chores, while theirsekitoricounterparts may relax, or deal with work issues related to their fan clubs. Younger wrestlers also attend classes, although their education differs from the typical curriculum of their non-sumo peers. In the evening,sekitorimay go out with their sponsors, while the junior wrestlers generally stay at home in the stable, unless they are to accompany the stablemaster or asekitorias histsukebito(manservant) when he is out. Becoming atsukebitofor a senior member of the stable is a typical duty. Asekitorihas a number oftsukebito,depending on the size of the stable or in some cases depending on the size of thesekitori.The junior wrestlers are given the most mundane tasks such as cleaning the stable, running errands, and even washing or massaging the exceptionally largesekitoriwhile only the seniortsukebitoaccompany thesekitoriwhen he goes out.

Thesekitoriare given their own room in the stable, or may live in their own apartments, as do married wrestlers; the junior wrestlers sleep in communal dormitories. Thus, the world of the sumo wrestler is split broadly between the junior wrestlers, who serve, and thesekitori,who are served. Life is especially harsh for recruits, to whom the worst jobs tend to be allocated, and the dropout rate at this stage is high.

The negative health effects of the sumo lifestyle can become apparent later in life. Sumo wrestlers have alife expectancyof 65,[36]which is about 15 years shorter than that of the average Japanese male, as the diet and sport take a toll on the wrestler's body. Those having a higher body mass are at greater risk of death.[37][38]Many developtype 2 diabetesorhigh blood pressure,and they are prone to heart attacks due to the enormous amount of body mass and fat that they accumulate. The excessive intake ofalcoholcan lead toliver problemsand the stress on their joints due to their excess weight can causearthritis.[36]The repeated blows to the head sumo wrestlers take can also causelong-term cognitive issues,similar to those seen in boxers.[39][40]In the 21st century the standards of weight gain became less strict to try and increase the health of the wrestlers.[36][41][39]

Salary and payment[edit]

As of 2018[update],the monthly salary figures (inJapanese yen) for the top two divisions were:[42]

- yokozuna:¥3 million, about US$26,500

- ōzeki:¥2.5 million, about US$22,000

- san'yaku:¥1.8 million, about US$16,000

- maegashira:¥1.4 million, about US$12,500

- jūryō:¥1.1 million, about US$9,500

Wrestlers lower than the second-highest division, who are considered trainees, receive only a fairly small allowance instead of a salary.

In addition to the basic salary,sekitoriwrestlers also receive additional bonus income, calledmochikyūkin,six times a year (once every tournament, orbasho) based on the cumulative performance in their career to date. This bonus increases every time the wrestler scores akachikoshi(with largerkachikoshigiving larger raises). Special increases in this bonus are also awarded for winning the top division championship (with an extra large increase for a "perfect" championship victory with no losses orzenshō-yūshō), and also for scoring a gold star orkinboshi(an upset of ayokozunaby amaegashira).

San'yakuwrestlers also receive a relatively small additional tournament allowance, depending on their rank, andyokozunareceive an additional allowance every second tournament, associated with the making of a newtsunabelt worn in their ring entering ceremony.

Also, prize money is given to the winner of each divisional championship, which increases from ¥100,000 for ajonokuchivictory up to ¥10 million for winning the top division. In addition to prizes for a championship, wrestlers in the top division giving an exceptional performance in the eyes of a judging panel can also receive one or more of three special prizes (thesanshō), which are worth ¥2 million each.[43]

Individual top division matches can also be sponsored by companies, with the resulting prize money calledkenshōkin.[16]For bouts involvingyokozunaandōzeki,the number of sponsors can be quite large, whereas for lower-ranked matchups, no bout sponsors may be active at all unless one of the wrestlers is particularly popular, or unless a company has a policy of sponsoring all his matchups. As of 2019[update],a single sponsorship cost ¥70,000, with ¥60,000 going to the winner of the bout and ¥10,000 deducted by the Japan Sumo Association for costs and fees.[44]Immediately after the match, the winner receives an envelope from the referee with half of his share of the sponsorship, while the other half is put in a fund for his retirement.[44]No prize money is awarded for bouts decided by afusenshōor forfeit victory.

Amateur sumo[edit]

Sumo is also practiced as anamateur sportin Japan, with participants in college, high school, grade school or company workers onworks teams.Open amateur tournaments are also held. The sport at this level is stripped of most of the ceremony. Most new entries into professional sumo are junior high school graduates with little to no previous experience,[45]but the number of wrestlers with a collegiate background in the sport has been increasing over the past few decades.[46]The International Herald Tribunereported on this trend in November 1999, when more than a third of the wrestlers in the top two divisions were university graduates.[47]Nippon Sport Science UniversityandNihon Universityare the colleges that have produced the most professional sumo wrestlers.[45]The latter producedHiroshi Wajima,who in 1973 became the first, and remains the only, wrestler with a collegiate background to attain the rank ofyokozuna.[46]

The most successful amateur wrestlers (usually college champions) are allowed to enter professional sumo atmakushita(third division) orsandanme(fourth division) rather than from the very bottom of the ladder. These ranks are calledmakushita tsukedashiandsandanme tsukedashi,and are currently equivalent tomakushita10,makushita15, orsandanme100 depending on the level of amateur success achieved. All amateur athletes entering the professional ranks must be under 23 to satisfy the entry, except those who qualify formakushita tsukedashiorsandanme tsukedashi,who may be up to 25.

TheInternational Sumo Federationwas established to encourage the sport's development worldwide, including holding international championships. A key aim of the federation is to have sumo recognized as anOlympic sport.Accordingly, amateur tournaments are divided into weight classes (men: Lightweight up to 85 kg (187 lb), Middleweight up to 115 kg (254 lb), Heavyweight over 115 kg (254 lb), and Open Weight (unrestricted entry), and include competitions for female wrestlers (Lightweight up to 65 kg (143 lb), Middleweight up to 80 kg (180 lb), Heavyweight over 80 kg (180 lb), and Open Weight).

Amateur sumo clubs are gaining in popularity in the United States, with competitions regularly being held in major cities across the country. The US Sumo Open, for example, was held in the Los Angeles Convention Center in 2007 with an audience of 3,000.[48]The sport has long been popular on the West Coast and in Hawaii, where it has played a part in the festivals of the Japanese ethnic communities. Now, however, the sport has grown beyond the sphere ofJapanese diasporaand athletes come from a variety of ethnic, cultural, and sporting backgrounds.

Amateur sumo is particularly strong in Europe. Many athletes come to the sport from a background injudo,freestyle wrestling,or othergrapplingsports such assambo.Some Eastern European athletes have been successful enough to be scouted into professional sumo in Japan, much like their Japanese amateur counterparts. The most notable of these to date is the BulgarianKotoōshū,who is the highest-ranking foreign wrestler who was formerly an amateur sumo athlete.

Brazil is another center of amateur sumo, introduced by Japanese immigrants who arrived during the first half of the twentieth century. The first Brazilian sumo tournament was held in 1914.[49]Sumo took root in immigrant centers in southern Brazil, especially São Paulo, which is now home to the only purpose-built sumo training facility outside Japan.[50]Beginning in the 1990s, Brazilian sumo organizations made an effort to interest Brazilians without Japanese ancestry in the sport, and by the mid-2000s an estimated 70% of participants came from outside the Japanese-Brazilian community.[49]Brazil is also a center for women's sumo.[50]A small number of Brazilian wrestlers have made the transition to professional sumo in Japan, includingRyūkō GōandKaisei Ichirō.

Clothing[edit]

Sumo wrestlers wearmawashi,a 30-foot-long belt, that they tie in knots in the back.[51]They have an official thickness and strength requirement. During matches, the wrestler will grab onto the other wrestler'smawashiand use it to help them and make moves during a match.[52]Themawashithey wear practicing versus in a tournament is essentially the same except for the material. The differentmawashithat the wrestlers wear differentiate their rank. Top rated wrestlers wear different colors of silkmawashiduring tournament, while lower rated wrestlers are limited to just black cotton.[52]

Their hair is put in a topknot, and wax is used to get the hair to stay in shape. Wax is applied to sumo wrestlers' hair daily by sumo hairdressers (tokoyama).[53]The topknot is a type of samurai hairstyle which was once popular in Japan during theEdo period.[53]The topknot is hard for some foreigners' hair because their hair is not as coarse and straight as Japanese hair. Once a wrestler joins a stable, he is required to grow out his hair in order to form a topknot.[53]

Outside of tournaments and practices, in daily life, sumo wrestlers are required to wear traditional Japanese clothes.[54]They must wear these traditional clothes all the time in public. What they can wear in public is also determined by rank. Lower rated wrestlers must wear ayukataat all times, even in winter, where higher rated wrestlers have more choice in what they wear.[54]

Gallery[edit]

-

Initialfull squatwith heels up,Sonkyo(Ngồi xổm)in Japanese

-

Partial squatbefore engaging

-

Yumitori-shiki

See also[edit]

- Controversies in professional sumo

- Culture of Japan

- Glossary of sumo terms

- Kimarite,list of winning moves in sumo

- List of active sumo wrestlers

- List of past sumo wrestlers

- List of sumo stables

- List of sumo record holders

- List of sumo tournament top division champions

- List of sumo tournament second division champions

- List of sumo video games

- List of years in sumo

- List of yokozuna

- Lists of sumo wrestlers

- Ssireum,traditional Korean wrestling

- Robot-sumo,robot competition inspired by sumo

- Naki Sumo Crying Baby Festival

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^"Sumo".Archivedfrom the original on June 9, 2020.RetrievedMay 15,2020.

- ^"What Is Sumo?".Kids Web Japan.Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2019.RetrievedMay 16,2020.

- ^"Yoroku: The pride of Japan's 'national sport'".The Mainichi.January 25, 2016.Archivedfrom the original on December 30, 2022.RetrievedDecember 30,2022.

- ^"Decline in apprentices threatens future of national sport".Asahi Shimbun.Archived fromthe originalon June 28, 2013.RetrievedJune 23,2013.

- ^"Revival of sumo's popularity"(in Japanese). Saga Shinbun.Archivedfrom the original on January 5, 2015.RetrievedDecember 8,2014.

- ^abcdeSharnoff, Lora (August 13, 2013)."History of Sumo".USA Dojo.Archivedfrom the original on December 29, 2019.RetrievedDecember 29,2019.

- ^abcdBlaine Henry (April 14, 2020)."History Lesson: Sumo Wrestling's Ancient Origins".Fight-Library.Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2020.RetrievedApril 26,2020.

- ^Ashkenazi, Michael (2003).Handbook of Japanese Mythology.ABC-CLIO. p.266.ISBN9781576074671.

- ^abShigeru Takayama."Encyclopedia of Shinto: Sumō".Kokugakuin University. Archived fromthe originalon November 24, 2020.RetrievedDecember 29,2019.

- ^"Nam tử lập tượng ( lực sĩ giống ) đất sét luân văn hóa di sản オンライン".bunka.nii.ac.jp(in Japanese).RetrievedJune 4,2023.

- ^Worth Davison, Michael, ed. (1993).When, Where, Why, and How It Happened.Reader's Digest. p. 243.

- ^"Winning a Sumo Bout".Kids Web Japan.Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2020.RetrievedMay 16,2020.

- ^"Kimarite Menu".Japan Sumo Association.Archived fromthe originalon July 9, 2009.RetrievedJanuary 20,2010.

- ^abHall, Mina (1997).The Big Book of Sumo: History, Practice, Ritual, Fight.Stone Bridge Press.ISBN1-880656-28-0.

- ^Pathade, Mahesh."what is Dohyo".Kheliyad.Archived fromthe originalon March 17, 2020.RetrievedMarch 9,2020.

- ^abcdefghijklmMorita, Hiroshi."Sumo Q&A".NHK World-Japan.Archivedfrom the original on December 7, 2019.RetrievedDecember 25,2020.

- ^abcdSharnoff, Lora (1993).Grand Sumo.Weatherhill.ISBN0-8348-0283-X.

- ^"Rules of Sumo".Beginner's Guide of Sumo.Japan Sumo Association.Archived fromthe originalon June 1, 2007.RetrievedJune 26,2007.

- ^"SUMO/ Heavier wrestlers blamed for increase in serious injuries".Asahi Shimbun.February 19, 2019. Archived fromthe originalon February 28, 2019.RetrievedMarch 8,2019.

- ^"Sumo Beya Guide".Japan Sumo Association.Archived fromthe originalon July 15, 2007.RetrievedJuly 8,2007.

- ^Ashmun, Chuck (1994)."Wrestlers Go Great Lengths To Qualify".Seattle Times.Archivedfrom the original on October 15, 2018.RetrievedOctober 15,2018.

- ^"Silicone Raises Sumo Hopeful to New Heights".July 7, 1994.Archivedfrom the original on March 18, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 20,2020– via LA Times.

- ^Gunning, John(January 13, 2019)."Sumo 101: Becoming a rikishi".The Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 7, 2020.RetrievedAugust 13,2020.

- ^"Want to be a sumo wrestler? Weight, height no longer matter".The Asahi Shimbun.September 29, 2023.RetrievedOctober 27,2023.

- ^Kamiya, Setsuko (February 19, 2010)."Steeped in tradition, Shinto, sumo is also scandal-stained".Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on August 25, 2017.RetrievedAugust 16,2017.

- ^ab"Banzuke".Beginner's Guide of Sumo.Japan Sumo Association.Archived fromthe originalon June 30, 2007.RetrievedJune 27,2007.

- ^"Sumo FAQ - Professional rankings: The Banzuke".scgroup.Archived fromthe originalon October 1, 2012.

- ^"SumoDB Ozeki promotion search".Archivedfrom the original on April 3, 2023.RetrievedAugust 4,2020.

- ^Yoshida, Reiji (April 30, 2018)."Banning women from the sumo ring: centuries-old tradition, straight-up sexism or something more complex?".The Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on May 16, 2021.RetrievedDecember 11,2019.

- ^Pathade, Mahesh."women sumo wrestling restrictions".Kheliyad.RetrievedMarch 9,2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^"Female Medics Rushed to Help a Man Who Collapsed on a Sumo Ring. They Were Promptly Told to Leave".news.yahoo.April 5, 2018.Archivedfrom the original on August 11, 2019.RetrievedDecember 1,2020.

- ^Miki, Shuji (April 21, 2018)."SUMO ABC (75) / Banning women from the dohyo is groundless in this day and age - The Japan News".Japan News/Yomiuri Shimbun. Archived fromthe originalon April 23, 2018.RetrievedApril 23,2018.

- ^"すみだスポット - quốc kỹ quán | giống nhau xã đoàn pháp nhân mặc điền khu quan quang hiệp hội 【 bổn vật が sinh きる phố すみだ quan quang サイト】".July 5, 2015.

- ^An exception to this rule occurred whenHirohito,the formerEmperor of Japan,died on Saturday, January 7, 1989. The tournament that was to start on the following day was postponed to start on Monday, January 9 and finish on Monday, January 24.

- ^Seales, Rebecca (December 1, 2017)."Inside the scandal-hit world of sumo".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on September 25, 2018.RetrievedOctober 1,2018.

- ^abcd"Becoming a Sumo Wrestler".Sumo East and West.Discovery Channel.Archived fromthe originalon August 31, 2005.RetrievedNovember 18,2005.

- ^Hoshi, Akio; Inaba, Yutaka (1995)."Risk Factors for Mortality and Mortality Rate of Sumo Wrestlers".Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi (Japanese Journal of Hygiene).50(3): 730–736.doi:10.1265/jjh.50.730.ISSN0021-5082.PMID7474495.

- ^Kanda, Hideyuki; Hayakawa, Takehito; Tsuboi, Satoshi; Mori, Yayoi; Takahashi, Teruna; Fukushima, Tetsuhito (2009)."Higher Body Mass Index is a Predictor of Death Among Professional Sumo Wrestlers".Journal of Sports Science & Medicine.8(4): 711–712.ISSN1303-2968.PMC3761530.PMID24137100.

- ^abSuzuki, Takahiro (2018)."Quý nãi hoa vấn đề で ai も xúc れない hoành cương の リアル thọ mệnh"[Yokozuna's real life span that no one touches on the Takanohana issue].Toyo Keizai.

- ^McCurry, Justin (February 6, 2021)."Conservative world of sumo slow to take action on concussion".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.RetrievedJuly 3,2023.

- ^"United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics".Archivedfrom the original on September 21, 2004.RetrievedNovember 18,2005.

- ^"Rikishi Salaries"(in Japanese). November 29, 2018.Archivedfrom the original on May 28, 2019.RetrievedDecember 3,2018.

- ^"Sumo Questions".Archivedfrom the original on April 28, 2006.RetrievedNovember 18,2005.

- ^ab"Thu nơi から tiền thưởng truy nã ngạch アップ, tay lấy り変わらず tích lập kim ↑"(in Japanese).Nikkan Sports.May 30, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2020.RetrievedJuly 22,2020.

- ^abGunning, John (March 18, 2019)."Sumo 101: College graduates in sumo".The Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2021.RetrievedDecember 25,2020.

- ^abGunning, John (November 11, 2020)."Universities offer foreign wrestlers new path to pro sumo".The Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 25, 2020.RetrievedDecember 25,2020.

- ^Kattoulas, Velisarios (November 9, 1999)."College Sumo Wrestlers Overshadow Old Guard".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on May 12, 2021.RetrievedDecember 25,2020.

- ^My First Date With Sumo (2007) Gould, ChrisArchivedSeptember 28, 2012, at theWayback Machine

- ^abBenson, Todd (January 27, 2005)."Brazil's Japanese Preserve Sumo and Share It With Others".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 1, 2017.RetrievedNovember 21,2016.

- ^abKwok, Matt (August 2, 2016)."'Sumo feminino': How Brazil's female sumo wrestlers are knocking down gender barriers ".CBC News.Archivedfrom the original on November 22, 2016.RetrievedNovember 21,2016.

- ^"Sumo Equipment".December 5, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on November 16, 2019.RetrievedNovember 22,2019.

- ^ab"What Do Sumo Wrestlers Wear During a Match?".LIVESTRONG.COM.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2019.RetrievedOctober 19,2019.

- ^abc"The Topknot".Sportsrec.September 14, 2018.Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2020.RetrievedNovember 22,2019.

- ^ab"Things You Didn't Know About Sumo Wrestlers".September 16, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on December 7, 2019.RetrievedDecember 7,2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Adams, Andy; Newton, Clyde (1989).Sumo.London, UK: Hamlyn.ISBN0600563561.

- Benjamin, David (2010).Sumo: A Thinking Fan's Guide to Japan's National Sport.North Clarendon, Vermont, USA: Tuttle Publishing.ISBN978-4-8053-1087-8.

- Bickford, Lawrence (1994).Sumo And The Woodblock Print Masters.Tokyo, New York: Kodansha International.ISBN4770017529.

- Buckingham, Dorothea M. (1997).The Essential Guide to Sumo.Honolulu, USA: Bess Press.ISBN1880188805.

- Cuyler, P.L.; Simmons, Doreen (1989).Sumo From Rite to Sport.New York: Weatherhill.ISBN0834802031.

- Hall, Mina (1997).The Big Book of Sumo.Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press.ISBN1880656280.

- Ito, Katsuharu (2017).The Perfect Guide To Sumo, in Japanese and English.Translated by Shapiro, David. Kyoto, Japan: Seigensha.ISBN978-4-86152-632-9.

- Kenrick, Douglas M. (1969).The Book of Sumo: Sport, Spectacle, and Ritual.New York: Weatherhill.ISBN083480039X.

- Newton, Clyde (2000).Dynamic Sumo.New York and Tokyo: Kodansha International.ISBN4770025084.

- Patmore, Angela (1991).The Giants of Sumo.London, UK: Macdonald Queen Anne Press.ISBN0356181200.

- PHP Institute; Kitade, Seigoro, eds. (1998).Grand Sumo Fully Illustrated.Translated by Iwabuchi, Deborah. Tokyo: Yohan Publications.ISBN978-4-89684-251-7.

- Sacket, Joel (1986).Rikishi The Men of Sumo.text by Wes Benson. New York: Weatherhill.ISBN0834802147.

- Sargent, John A. (1959).Sumo The Sport and The Tradition.Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Company.ISBN0804810842.

- Schilling, Mark (1984).Sumo: A Fan's Guide.Tokyo, Japan: The Japan Times, Ltd.ISBN4-7890-0725-1.

- Shapiro, David (1995).Sumo: A Pocket Guide.Rutland, Vermont, USA & Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company.ISBN0-8048-2014-7.

- Sharnoff, Lora (1993) [1st pub. 1989].Grand Sumo: The Living Sport and Tradition(2nd ed.). New York: Weatherhill.ISBN0-8348-0283-X.

- Sports Watching Association (Japan); Kakuma, Tsutomu, eds. (1994).Sumo Watching.Translated by Iwabuchi, Deborah. New York: Weatherhill.ISBN4896842367.

- Takamiyama, Daigoro;Wheeler, John (1973).Takamiyama The World of Sumo.Tokyo, New York: Kodansha International.ISBN0870111957.

- Yamaki, Hideo (2017).Discover Sumo: Stories From Yobidashi Hideo.Translated by Newton, Clyde. Tokyo: Gendai Shokan.ISBN978-4768457986.