Sun Yat-sen

Guófù( quốc phụ ) Sun Yat-sen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tôn Trung Sơn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sun in the 1910s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Provisional President of the Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 January 1912 – 10 March 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Li Yuanhong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yuan Shikai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier of the Kuomintang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 October 1919 – 12 March 1925 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Zhang Renjie(as Chairman) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Sun Te-ming (Tôn đức minh) 12 November 1866 Cuiheng,Guangdong, Qing dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 12 March 1925(aged 58) Peking Union Medical College Hospital,Beijing,Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Kuomintang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4, includingSun Fo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese(MD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Politician, writer, physician | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature (Chinese) |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Republic of China Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1917–1925 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Grand marshal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common name in English (Sun Yat-sen) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Tôn dật tiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Tôn dật tiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sūn Yìxiān | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Syun1 Jat6-sin1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common name in Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Tôn Trung Sơn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Tôn Trung Sơn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sūn Zhōngshān | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Syun1 Zung1-saan1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Tôn tái chi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Tôn tái chi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sūn Zàizhī | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Syun1 Zoi3-zi1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sun Yat-sen(/ˈsʊnˈjɑːtˈsɛn/;[1]traditional Chinese:Tôn dật tiên;simplified Chinese:Tôn dật tiên;pinyin:Sūn Yìxiān;12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)[2][3][4][a]was a Chinese revolutionary, statesman, andpolitical philosopherwho served as theprovisional first presidentof theRepublic of Chinaand the first leader of theKuomintang(KMT). Uniquely among 20th-century Chinese leaders, Sun is revered by both theRepublic of Chinaon Taiwan (where he is officially the "Father of the Nation") and by thePeople's Republic of China(where he is officially the "Forerunner of the Revolution" ) for his instrumental role in the1911 Revolutionthat successfully overthrew theQing dynasty.[5]

Educated overseas, Sun is considered one of the most important leaders of modern China, but his political life featured constant struggles and frequent periods of exile. After the success of the 1911 Revolution, Sun quickly resigned as president of the nascent Republic of China, relinquishing the position to the generalYuan Shikaiand ultimately going into exile in Japan. He later returned to found a revolutionary government inSouthern Chinato challenge thewarlordswho controlled much of the country following Yuan's death. In 1923, Sun invited representatives of theCommunist InternationaltoGuangzhouto reorganize the KMT, resulting in the brittleFirst United Frontwith theChinese Communist Party(CCP). He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor,Chiang Kai-shek,in theNorthern Expedition.Now residing in Beijing, Sun died of gallbladder cancer in 1925.[6]

A vital component of Sun's legacy is his political philosophy, known as theThree Principles of the People:the peoples' independence from foreign domination, their rights, and their livelihood.[7][8][9]He also composed the lyrics to theNational Anthem of the Republic of China.

Names

[edit]

Sun'sgenealogical namewasSun Deming(Syūn Dāk-mìhng;Tôn đức minh).[3][10]As a child, hispet namewas Tai Tseung (Dai-jeuhng;Đế tượng).[3]In school, the teacher gave him the nameSun Wen(Cantonese:Syūn Màhn;Tôn văn), which was used by Sun for most of his life. Sun'scourtesy namewas Zaizhi (Jai-jī;Tái chi), and his baptized name was Rixin (Yaht-sān;Ngày tân).[11]While at school inHong Kong under British rule,he got theart nameYat-sen (Chinese:Dật tiên;pinyin:Yìxiān).[12]Sun Zhongshan(Tôn Trung Sơn;Cantonese:syūn jūng sāan,romanizedChung Shan), the most popular of his Chinese names in China, is derived from hisJapanese nameKikori Nakayama(Trung sơn tiềuNakayama Kikori), the pseudonym given to him byTōten Miyazakiwhen he was in hiding in Japan.[3]His birthplace city was renamedZhongshanin his honour probably shortly after his death in 1925 and uses that name. Zhongshan is one of the fewcities named after peoplein China and has remained as the official name of the city during Communist rule.

Early years

[edit]Birthplace and early life

[edit]Sun Te-ming was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng andMadame Yang.[4]His birthplace was the village ofCuiheng,Xiangshan County(nowZhongshanCity), Canton Province (nowGuangdong).[4]He is ofHakka[13][14]descent. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor inMacauand as a journeyman and a porter.[15]After finishing primary education and meeting childhood friendLu Haodong,[3]he moved toHonoluluin theKingdom of Hawaii,where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brotherSun Mei.[16][17][18][19]

Education

[edit]

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun began his education at the age of 10,[3]attending secondary school in Hawaii.[20]In 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, a 13-year-old Sun went to live with his elder brotherSun Mei,[3]who would later make major contributions to overthrowing theQing dynasty,and who financed Sun's attendance of theʻIolani School.[16][17][18][19]There, he studied English,British history,mathematics, science, and Christianity.[3]Sun was initially unable to speak English, but quickly acquired it, received a prize for academic achievement from KingKalākaua,and graduated in 1882.[21]He then attendedOahu College(now known asPunahou School) for one semester.[3][22]By 1883, Sun's interest in Christianity had become deeply worrisome for his brother—who, seeing his conversion as inevitable, sent Sun back to China.[3]

Upon returning to China, a 17-year-old Sun met with his childhood friend Lu Haodong at the Beiji Temple (Bắc cực điện) in Cuiheng,[3]where villagers engaged in traditionalfolk healingand worshipped aneffigyof the Beiji (literally 'North Pole') emperor-god. Feeling contemptuous of these practices,[3]Sun and Lu incurred the wrath of their fellow villagers by breaking the wooden idol; as a result, Sun's parents felt compelled to dispatch him to Hong Kong.[3][23]In November 1883, Sun began attending the Diocesan Home and Orphanage onEastern Street(now theDiocesan Boys' School),[24][25]and from 15 April 1884 he attended The Government Central School onGough Street(nowQueen's College), until graduating in 1886.[26][27]

In 1886, Sun studied medicine at theGuangzhou Boji Hospitalunder the Christian missionaryJohn Glasgow Kerr.[3]According to his book "Kidnapped in London", in 1887 Sun heard of the opening of theHong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese(the forerunner of theUniversity of Hong Kong).[28]He immediately sought to attend, and went on to obtain a license to practice medicine from the institution in 1892;[3][12]out of a class of twelve students, Sun was one of two who graduated.[29][30][31]

Religious views and Christian baptism

[edit]In the early 1880s, Sun Mei had sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of theChurch of Hawaiiand directed by anAnglicanprelate,Alfred Willis,with the language of instruction being English. At the school, the young Sun first came in contact with Christianity.

Sun was laterbaptizedin Hong Kong (on 4 May 1884) byRev.Charles Robert Hager[32][33][34]an American missionary of theCongregational Church of the United States(American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions) to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[35][36]Sun attended To Tsai Church (Nói tế hội đường), founded by theLondon Missionary Societyin 1888,[37]while he studied medicine inHong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of theChristian church.His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[36]

Becoming a revolutionary

[edit]Four Bandits

[edit]

During the Qing-dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers, nicknamed theFour Bandits,at theHong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.[38]

From Furen Literary Society to Revive China Society

[edit]In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong includingYeung Ku-wanwho was the leader and founder of theFuren Literary Society.[39]The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000-character petition to QingViceroyLi Hongzhangpresenting his ideas for modernizing China.[40][41][42]He traveled toTianjinto personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience.[43]After that experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded theRevive China Society,which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. It was the first Chinese nationalist revolutionary society.[44]Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially from the lower social classes. The same month in 1894, the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.[39]Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China Society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.[45]They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club"[46]: 90 (Càn hừ hành).

Heaven and Earth Society and overseas travels to seek financial support

[edit]A "Heaven and Earth Society" sect known asTiandihuihad been around for a long time.[47]The group has also been referred to as the "three cooperating organizations", as well as thetriads.[47]Sun mainly used the group to leverage his overseas travels to gain further financial and resource support for his revolution.[47]

First Sino-Japanese War

[edit]In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during theFirst Sino-Japanese War.There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that theManchuQing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.[48]Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals likeKang YouweiandLiang Qichaosupported responding with initiatives like theHundred Days' Reform.[48]In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others likeZou Rongwanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modernnation-statein the form of arepublic.[48]The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.[49]

First uprising and exile

[edit]First Guangzhou Uprising

[edit]

In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China Society, on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched theFirst Guangzhou uprisingagainst the Qing inGuangzhou.[41]Yeung Ku-wandirected the uprising starting from Hong Kong.[45]However, plans were leaked out, and more than 70 members, includingLu Haodong,were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother, who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.[16]Additionally, members of his family and relatives of Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole inKula,Maui.[16][17][18][19][50]

Exile in Japan

[edit]While in exile inLondonin 1896, Sun raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, Sun Yat-sen was detained at theChinese Legation in London,where the Chinese secret service planned to smuggle him back to China to execute him for his revolutionary actions.[51]He was released after 12 days by the efforts ofJames Cantlie,The Globe,The Times,and theForeign Office,which left Sun a hero in the United Kingdom.[note 1]James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and later wrote an early biography of him[53]Sun wrote a book in 1897 about his detention, "Kidnapped in London."[28]

Sun traveled by way ofCanadatoJapanto begin his exile there. He arrived inYokohamaon 16 August 1897 and met with the Japanese politicianTōten Miyazaki.Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by apan-Asianopposition toWestern imperialism.[54]In Japan, Sun also met and befriendedMariano Ponce,a diplomat of theFirst Philippine Republic.[55]

During thePhilippine Revolutionand thePhilippine–American War,Sun helped Ponce procure weapons that had been salvaged from theImperial Japanese Armyand ship the weapons to the Philippines. By helping the Philippine Republic, Sun hoped that the Filipinos would win their independence so that he could use its islands as a staging point of another revolution. However, as the war ended in July 1902, the United States emerged victorious from a bitter three-year war against the Republic. Therefore, the Filipino dream of independence vanished with Sun's hopes of allying with the Philippines in his revolution in China.[56]

From failed uprisings to revolution

[edit]Huizhou Uprising

[edit]On 22 October 1900, Sun ordered the launch of theHuizhou Uprisingto attackHuizhouand provincial authorities in Guangdong.[57]That came five years after the failed Guangzhou Uprising. This time, Sun appealed to thetriadsfor help.[58]The uprising was another failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of the revolutionary effort under the title "33-Year Dream" (33 năm chi mộng) in 1902.[59][60][61]

Getting support from Siamese Chinese

[edit]In 1903, Sun made a secret trip toBangkokin which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals amongSiamese ChineseinSiam.In Bangkok, Sun visitedYaowarat Road,in the city'sChinatown.On that street, Sun gave a speech claiming thatOverseas Chinesewere "the Mother of the Revolution." He also met the local Chinese merchant Seow Houtseng,[62]who sent financial support to him.

Sun's speech on Yaowarat Road was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" (Thai:ซอยซุนยัตเซ็น) in his honour.[63]

Getting support from American Chinese

[edit]According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States since theChinese Exclusion Act of 1882would have otherwise blocked him.[64]

In March 1904, while residing inKula,Maui,Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by theTerritory of Hawaii,stating that "he was born in theHawaiian Islandson the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870. "[65][66]He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act.[66]Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.[67]

On 6 April 1904, on his first attempt to enter the United States, Sun Yat-sen landed inSan Francisco.He was detained and faced with possible deportation.[64]Sun, represented by the law firm of Ralston & Siddons, based inWashington DC,filed an appeal with the Commissioner-General of Immigration on 26 April 1904. On 28 April 1904, the acting secretary of theDepartment of Commerce and Laborin a four-page decision contained in the case file, set aside the order of deportation and ordered the Commissioner of Immigration in San Francisco to "permit the said Sun Yat-sen to land." Sun was then freed to embark on his fundraising tour in the United States.[64]

Unifying forces of Tongmenghui in Tokyo

[edit]

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel theTatarbarbarians (specifically, the Manchu), to reviveZhonghua,to establish a Republic, and todistribute landequally among the people "(Loại bỏ thát lỗ, khôi phục Trung Hoa, sáng lập dân quốc, bình quân quyền sở hữu ruộng đất).[68]One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of theThree Principles of the People.These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu,Dân tộc), of democracy (minquan,Dân quyền), and of welfare (minsheng,Dân sinh).[68]

On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo to form the unified groupTongmenghui(United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.[68][69]By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963.[68]

Getting support from Malayan Chinese

[edit]

Sun's notability and popularity extended beyond theGreater Chinaregion, particularly toNanyang(Southeast Asia), where a large concentration ofoverseas Chineseresided inMalaya(Malaysiaand Singapore). In Singapore, he met the local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock (Trương Vĩnh Phúc), Tan Chor Nam (Trần sở nam) and Lim Nee Soon (Lâm nghĩa thuận), which mark the commencement of direct support from theNanyangChinese. The Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui was established on 6 April 1906,[71]but some records claim the founding date to be end of 1905.[71]Thevillaused by Sun was known asWan Qing Yuan.[71][72]Singapore then was the headquarters of the Tongmenghui.[71]

After founding the Tongmenghui, Sun advocated the establishment of theChong Shing Yit Paoas the alliance's mouthpiece to promote revolutionary ideas. Later, he initiated the establishment of reading clubs across Singapore and Malaysia to disseminate revolutionary ideas by the lower class through public readings of newspaper stories. The United Chinese Library, founded on 8 August 1910, was one such reading club, first set up at leased property on the second floor of the Wan He Salt Traders in North Boat Quay.[73]

The first actual United Chinese Library building was built between 1908 and 1911 below Fort Canning, on 51 Armenian Street, commenced operations in 1912. The library was set up as a part of the 50 reading rooms by the Chinese republicans to serve as an information station and liaison point for the revolutionaries. In 1987, the library was moved to its present site at Cantonment Road.

Uprisings

[edit]On 1 December 1907, Sun led theZhennanguan Uprisingagainst the Qing atFriendship Pass,which is the border betweenGuangxiandVietnam.[74]The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.[74][75]In 1907, there were a total of four failed uprisings, includingHuanggang uprising,Huizhou seven women lake uprisingandQinzhou uprising.[71]In 1908, two more uprisings failed: theQin-lian UprisingandHekou Uprising.[71]

Anti-Sun factionalism

[edit]Because of the failures, Sun's leadership was challenged by elements from within the Tongmenghui who wished to remove him as leader. In Tokyo, members from the recently mergedRestoration societyraised doubts about Sun's credentials.[71]Tao ChengzhangandZhang Binglinpublicly denounced Sun in an open leaflet, "A declaration of Sun Yat-sen's Criminal Acts by the Revolutionaries in Southeast Asia",[71]which was printed and distributed in reformist newspapers likeNanyang Zonghui Bao.[71][76]The goal was to target Sun as a leader leading a revolt only forprofiteering.[71]

The revolutionaries were polarized and split between pro-Sun and anti-Sun camps.[71]Sun publicly fought off comments about how he had something to gain financially from the revolution.[71]However, by 19 July 1910, the Tongmenghui headquarters had to relocate from Singapore to Penang to reduce the anti-Sun activities.[71]It was also in Penang that Sun and his supporters would launch the first Chinese "daily" newspaper, theKwong Wah Yit Poh,in December 1910.[74]

1911 revolution

[edit]

To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at thePenang conference,held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.[77]The high-powered preparatory meeting of Sun's supporters was subsequently held in Ipoh, Singapore, at the villa of Teh Lay Seng, the chairman of the Tungmenghui, to raise funds for theHuanghuagang Uprising,also known as the Yellow Flower Mound Uprising.[78]The Ipoh leaders were Teh Lay Seng, Wong I Ek, Lee Guan Swee, and Lee Hau Cheong.[79]The leaders launched a major drive for donations across theMalay Peninsula[77]and raisedHK$187,000.[77]

On 27 April 1911, the revolutionaryHuang Xingled theYellow Flower MoundUprising against the Qing. The revolt failed and ended in disaster. The bodies of only 72 revolutionaries were identified of the 86 that were found.[80]The revolutionaries are remembered asmartyrs.[80] Despite the failure of this uprising, which was due to a leak, it was successful in triggering off the trend of nation-wide revolts.[81]

On 10 October 1911, the militaryWuchang Uprisingtook place and was led again by Huang Xing. The uprising expanded to theXinhai Revolution,also known as the "Chinese Revolution", to overthrow the last emperor,Puyi.[82]Sun had no direct involvement in it, as he was inDenver,Colorado,and had spent much of the year in the United States in search of support fromChinese Americans.That made Huang be in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. On 12 October, when Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States and was accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American "General"Homer Lea,an adventurer whom Sun had met in London when they attempted to arrange British financing for the future Chinese republic. Both sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.[83]

Republic of China with multiple governments

[edit]Provisional government

[edit]

On 29 December 1911, a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanjing elected Sun as theprovisional president.[84]1 January 1912 was set as theepochof the newrepublican calendar.[85]Li Yuanhongwas made provisional vice-president, and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. A newprovisional governmentfor the Republic of China was created, along with aprovisional constitution.Sun is credited for funding the revolutions and for keeping revolutionary spirit alive, even after a series of false starts. His successful merger of smaller revolutionary groups into a single coherent party provided a better base for those who shared revolutionary ideals. Under Sun's provisional government, several innovations were introduced, such as the aforementioned calendar system, and fashionableZhongshan suits.

Beiyang government

[edit]Yuan Shikai,who was in control of theBeiyang Army,had been promised the position of president of the Republic of China if he could get the Qing court to abdicate.[86]On 12 February 1912, the Emperor did abdicate the throne.[85]Sun stepped down as president, and Yuan became the new provisional president in Beijing on 10 March 1912.[86]The provisional government did not have any military forces of its own. Its control over elements of the new army that had mutinied was limited, and significant forces still had not declared against the Qing.

Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces to request them to elect and to establish theNational Assembly of the Republic of Chinain 1912.[87]In May 1912, the legislative assembly moved from Nanjing to Beijing, with its 120 members divided between members of the Tongmenghui and a republican party that supported Yuan Shikai.[88]Many revolutionary members were already alarmed by Yuan's ambitions and the northern-basedBeiyang government.

New Nationalist party in 1912, failed Second Revolution and new exile

[edit]The Tongmenghui memberSong Jiaorenquickly tried to control the assembly. He mobilized the old Tongmenghui at the core with the mergers of a number of new small parties to form a new political party, theKuomintang(Chinese Nationalist Party, commonly abbreviated as "KMT" ) on 25 August 1912 atHuguang Guild Hall,Beijing.[88]The1912–1913 National assembly electionwas considered a huge success for the KMT, which won 269 of the 596 seats in the lower house and 123 of the 274 seats in the upper house.[86][88]In retaliation, the KMT leaderSong Jiaorenwas assassinated, almost certainly by a secret order of Yuan, on 20 March 1913.[86]TheSecond Revolutiontook place by Sun and KMT military forces trying to overthrow Yuan's forces of about 80,000 men in an armed conflict in July 1913.[89]The revolt against Yuan was unsuccessful. In August 1913, Sun fled to Japan, where he later enlisted financial aid by the politician and industrialistFusanosuke Kuhara.[90]

Warlords chaos

[edit]In 1915, Yuan proclaimed theEmpire of Chinawith himself asEmperor of China.Sun took part in theNational Protection Warof theConstitutional Protection Movementand also supported bandit leaders likeBai Langduring theBai Lang Rebellion,which marked the beginning of theWarlord Era.In 1915, Sun wrote to theSecond International,asocialist-based organization inParis,and asked it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic.[91]The same year, Sun received theIndiancommunistM.N. Royas a guest.[92]There were thenmany theories and proposalsof what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen andXu Shichangwere announced as president of the Republic of China.[93]

Alliance with Communist Party and Northern Expedition

[edit]Guangzhou militarist government

[edit]

China had become divided among regional military leaders. Sun saw the danger and returned to China in 1916 to advocateChinese reunification.In 1921, he started a self-proclaimed military government inGuangzhouand was electedGrand Marshal.[94]Between 1912 and 1927, three governments were set up in South China: theProvisional government in Nanjing (1912),the Military government in Guangzhou (1921–1925), and the National government in Guangzhou and laterWuhan(1925–1927).[95]The governments in the south were established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.[94]Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short-livedChinese Revolutionary Partywas a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919, Sun resurrected the KMT with the new nameChung-kuoKuomintang,or "Nationalist Party of China."[88]

First United Front

[edit]

Sun was now convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period ofpolitical tutelage,which would culminate in the transition to democracy. To hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active co-operation with theChinese Communist Party(CCP). Sun and theSoviet Union'sAdolph Joffesigned theSun-Joffe Manifestoin January 1923.[5]Sun received help from theCominternfor his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Sun received assistance from Soviet advisorMikhail Borodin,whom Sun described as his "Lafayette".[96]: 54 The Russian revolutionary and socialist leaderVladimir Leninpraised Sun and his KMT for its ideology, principles, attempts at social reformation, and fight against foreign imperialism.[97][98][99]Sun also returned the praise by calling Lenin a "great man" and indicated that he wished to follow the same path as Lenin.[100]In 1923, after having been in contact with Lenin and other Moscow communists, Sun sent representatives to study theRed Army,and in turn, the Soviets sent representatives to help reorganize the KMT at Sun's request.[101]

With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for theNorthern Expeditionagainst the military at the north. He established theWhampoa Military Academynear Guangzhou withChiang Kai-shekas thecommandantof theNational Revolutionary Army(NRA).[102]Other Whampoa leaders includeWang JingweiandHu Hanminas political instructors. This full collaboration was called theFirst United Front.

Financial concerns

[edit]In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-lawT. V. Soongto set up the first Chinese central bank, theCanton Central Bank.[103]To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT.[104]However, Sun met opposition by theCanton Merchant Volunteers Corps Uprisingagainst him.

Final speeches

[edit]

In February 1923, Sun made a presentation to theStudents' UnioninHong Kong Universityand declared that the corruption of China and thepeace, order, and good governmentof Hong Kong had turned him into a revolutionary.[105][106]The same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed hisThree Principles of the Peopleas the foundation of the country and theFive-Yuan Constitutionas the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into theNational Anthem of the Republic of China.

On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north toTianjinand delivered a speech to suggest a gathering for a "national conference" for the Chinese people. He called for the end of warlord rules and the abolition of allunequal treatieswith theWestern powers.[107]Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Among the people whom he met was the Muslim warlord GeneralMa Fuxiang,who informed Sun that he would welcome Sun's leadership.[108]On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave aspeech on Pan-AsianismatKobe,Japan.[109]

Illness and death

[edit]For many years, it was popularly believed that Sun died ofliver cancer.On 26 January 1925, Sun underwent anexploratory laparotomyatPeking Union Medical College Hospital(PUMCH) to investigate a long-term illness. It was performed by the head of the Department of Surgery, Adrian S. Taylor, who stated that the procedure "revealed extensive involvement of the liver bycarcinoma"and that Sun had only about ten days to live. Sun was hospitalized, and his condition was treated withradium.[110]Sun survived the initial ten-day period, and on 18 February, against the advice of doctors, he was transferred to the KMT headquarters and treated withtraditional Chinese medicine.That was also unsuccessful, and he died on 12 March, at the age of 58.[111]Contemporary reports inThe New York Times,[111]Time,[112]and the Chinese newspaperQun Qiang Baoall reported the cause of death as liver cancer, based on Taylor's observation.[113]He also left ashort political will(Tổng lý di chúc), penned byWang Jingwei,which had a widespread influence in the subsequent development of theRepublic of ChinaandTaiwan.[114]

His body then was preserved inmineral oil[115]and taken to theTemple of Azure Clouds,aBuddhistshrine in theWestern Hillsa few miles outside Beijing.[116]A glass-covered steel coffin was sent by theSoviet Unionto the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall at Temple of Azure Clouds as a permanent repository for the body but was ultimately declined by the family as unsuitable.[117]The body was embalmed for preservation byPeking Union Medical Collegewho reportedly guaranteed its preservation for 150 years.[117]

In 1926, construction began on a majestic mausoleum at the foot ofPurple Mountainin Nanjing, which was completed in the spring of 1929. On 1 June 1929, Sun's remains were moved from Beijing and interred in theSun Yat-sen Mausoleum.

By pure chance, in May 2016, an American pathologist, Rolf F. Barth, was visiting theSun Yat-sen Memorial HallinGuangzhouwhen he noticed a faded copy of the original autopsy report on display. The autopsy was performed immediately after Sun's death by James Cash, a pathologist at PUMCH. Based on atissue sample,Cash concluded that the cause of death was anadenocarcinomain thegallbladderthat hadmetastasizedto the liver. In modern China, liver cancer is far more common thangallbladder cancer.Although the incidence rates for either one in 1925 are not known, if one assumes that they were similar at the time, the original diagnosis by Taylor was a reasonable conclusion. From the time of Sun's death to the appearance of Barth's report[110]in theChinese Journal of Cancerin September 2016, Sun's true cause of death was not reported in any English-language publication. Even in Chinese-language sources, it appeared in only one non-medical online report in 2013.[110][118]

Legacy

[edit]Power struggle

[edit]

After Sun's death, a power struggle between his young protégéChiang Kai-shekand his old revolutionary comradeWang Jingweisplit the KMT. At stake in the struggle was the right to lay claim to Sun's ambiguous legacy. In 1927, Chiang marriedSoong Mei-ling,a sister of Sun's widowSoong Ching-ling,and he could now claim to be a brother-in-law of Sun. When theCommunists and the Kuomintang splitin 1927, which marked the start of theChinese Civil War,each group claimed to be his true heirs, and the conflict that continued untilWorld War II.Sun's widow,Soong Ching-ling,sided with the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and was critical of Chiang's regime since theShanghai massacrein 1927. She served from 1949 to 1981 as vice-president (or vice-chairwoman) of the People's Republic of China and as honorary president shortly before her death in 1981.[119]

Personality cult

[edit]Apersonality cultin the Republic of China was centered on Sun and his successor,GeneralissimoChiang Kai-shek.The cult was created after Sun Yat-sen died. Chinese Muslim generals and imams participated in the personality cult and theone-party state,with Muslim GeneralMa Bufangmaking people bow to Sun's portrait and listen to the national anthem during aTibetanandMongolreligious ceremony for theQinghai Lakegod.[120]Quotes from theQur'anand theHadithwere used byHuiMuslims to justify Chiang's rule over China.[121]

The Kuomintang's constitution designated Sun as the party president. After his death, the Kuomintang opted to keep that language in its constitution to honor his memory forever. The party has since been headed by a director-general (1927–1975) and a chairman (since 1975), who discharge the functions of the president.[citation needed]

Though took a stance againstidolatryin life, Sun sometimes becameworshiped as a godamong people. For example, a KMT committee member Hsieh Kun-hong controversially referred to Sun as having "become immortal"after death under the posthumous name of" Great Merciful True Monarch "(Chinese:Vĩ từ chân quân) in 2021. Sun is already worshipped in the syncretic Vietnamese religion ofCaodaism.[122]

Father of the Nation

[edit]

Sun Yat-sen remains unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation in bothMainland ChinaandTaiwan.In Taiwan, he is seen as the Father of theRepublic of Chinaand is known by theposthumous nameFather of the Nation,Mr. Sun Zhongshan(Chinese:Quốc phụ Tôn Trung Sơn tiên sinh,and theone-character spaceis a traditional homage symbol).[10]

Forerunner of revolution

[edit]

In Mainland China, Sun is seen as a Chinese nationalist, a proto-socialist, and the first president of a Republican China and is highly regarded as the Forerunner of the Revolution (Cách mạng người mở đường).[5]He is even mentioned by name in thepreambleto theConstitution of the People's Republic of China.In recent years, the leadership of theChinese Communist Partyhas increasingly invoked Sun, partly as a way of bolsteringChinese nationalismin light of theChinese economic reformand partly to increase connections with supporters of the Kuomintang on Taiwan, which thePeople's Republic of Chinasees as allies againstTaiwan independence.Sun's tombwas one of the first stops made by the leaders of both the Kuomintang and thePeople First Partyon theirpan-blue visit to mainland China in 2005.[123]A massive portrait of Sun continues to appear inTiananmen Squarefor May Day andNational Day.

In 1956,Mao Zedongsaid, "Let us pay tribute to our great revolutionary forerunner, Dr. Sun Yat-sen!... he bequeathed to us much that is useful in the sphere of political thought."[124][125]

Xi Jinpingincorporates Sun's legacy into his discourse on national rejuvenation.[126]Xi describes Sun as the first person to propose a method for Chinese revival, including adopting the first blueprint for China's modernization.[126]

New Three Principles of the People

[edit]Sun's Three Principles of the People has been reinterpreted by the Chinese Communist Party to argue that communism is a necessary conclusion of them and thus provide legitimacy for the government. This reinterpretation of the Three Principles of the People is commonly referred to as the New Three Principles of the People (Chinese:Tân chủ nghĩa Tam Dân,also translated as "neo-tridemism" ), a word coined by Mao's 1940 essayOn New Democracyin which he argued that the Communist Party is a better enforcer of the Three Principles of the People compared to the bourgeois Kuomintang and that the new three principles are about allying with the communists and the Russians (Soviets) and supporting the peasants and the workers.[127]Proponents of the New Three Principles of the People claim that Sun's book Three Principles of the People acknowledges that the principles of welfare is inherently socialistic and communistic.[128]

During the 90th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution in 2001, former CCP General SecretaryJiang Zeminclaimed that Sun supposedly advocated for the "New Three Principles of the People."[129][130]In 2001, Sun's granddaughter Lily Sun said that the Chinese Communists were distorting Sun's legacy. She again voiced her displeasure in 2002 in a private letter to Jiang about the distortion of history.[129]In 2008 Jiang Zemin was willing to offer US$10 million to sponsor a Xinhai Revolution anniversary celebration event. According toMing Pao,she did not take the money because then she would not "have the freedom to properly communicate the Revolution."[129]

KMT emblem removal case

[edit]In 1981, Lily Sun took a trip to Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in Nanjing. The emblem of the KMT had been removed from the top of his sacrificial hall at the time of her visit but was later restored. On another visit in May 2011, she was surprised to find the four-character "General Rules of Meetings" (Hội nghị quy tắc chung), a document that Sun wrote in reference toRobert's Rules of Orderhad been removed from a stone carving.[129]

Founding father of the nation debate

[edit]In 1940, the Republic of China (ROC) government had bestowed the title of "father of the nation" on Sun. However, after 1949, as a result of the Chiang regime's arrival in Taiwan, his "father of the nation" designation continued only in Taiwan.[131]

Sun visited Taiwan briefly on only three occasions (in 1900, 1913, and 1918) or four by counting 1924, when his boat had stopped in Keelung Harbor, but he did not disembark.[131]

In November 2004, theTaiwanese Ministry of Educationproposed that Sun was not the father of Taiwan. Instead, Sun was a foreigner from mainland China.[132]Taiwanese Education MinisterTu Cheng-shengand theExamination YuanmemberLin Yu-ti,both of whom supported the proposal, had their portraits pelted with eggs in protest.[133]At a Sun Yat-sen statue inKaohsiung,a 70-year-old retired soldier of the Republic of China committed suicide on Sun's birthday, 12 November, to protest the ministry's proposal.[132][133]

Views

[edit]| Part ofa serieson |

| Three Principles of the People |

|---|

|

Western culture

[edit]As a lifelong Christian who never left Christianity, Sun Yat-sen was a loyal follower of Western modernity and Christianity[134]and saw it as the best way to develop the Chinese nation. He went on foreign trips to gather support and resources of Western and Christian nations.[135]He was highly critical of anything from ancient Chinese which didn't confirm to Western standards and idols, this led him and his group to break idols and denounce Chinese medicine amongst other things.[136][137]

Economic development

[edit]Sun Yat-sen spent years in Hawaii as a student in the late 1870s and early 1880s and was highly impressed with the economic development that he saw there. He used the Kingdom of Hawaii as a model to develop his vision of a technologically modern, politically independent, activelyanti-imperialistChina.[138]Sun, an important pioneer of international development, proposed in the 1920s international institutions of the sort that appeared after World War II. He focused on China, with its vast potential and weak base of mostly local entrepreneurs.[139]

His key proposal was socialism. He proposed:

- The State will take over all the large enterprises; we shall encourage and protect enterprises which may reasonably be entrusted to the people; the nation will possess equality with other nations; every Chinese will be equal to every other Chinese both politically and in his opportunities of economic advancement.[140]

He also proposed, "If we use existing foreign capital to build up a future communist society in China, half the work will bring double the results."[141][142][143]He also said, "It is my idea to make capitalism create socialism in China."[144][145]

Sun promoted the ideas of the economistHenry Georgeand was influenced byGeorgistideas on land ownership and aland value tax.[146][147]

Culture

[edit]Sun supportednatalismand hadeugenicideals.[148]: 41 He favored premarital health examinations,sterilizationof those perceived as unfit, and other programs for socially engineering China's population.[148]: 41–42 In Sun's view, China had only endured Western invasions and colonial rule because of its large population.[148]: 41 Those views led him to oppose the use ofbirth control.[148]: 41

Pan-Asianism

[edit]Sun was a proponent ofPan-Asianism.He said that Asia was the "cradle of the world's oldest civilisation" and that "even the ancient civilisations of the West, of Greece and Rome, had their origins on Asiatic soil." He thought that it was only in recent times that Asians "gradually degenerated and become weak."[149]For Sun, "Pan-Asianism is based on the principle of the Rule of Right, and justifies the avenging of wrongs done to others." He advocated overthrowing the Western "Rule of Might" and "seeking a civilisation of peace and equality and the emancipation of all races."[150]

Family

[edit]

Sun Yat-sen was born to Sun Dacheng (Tôn đạt thành) and his wife,Lady Yang(Dương thị) on 12 November 1866.[151]At the time, his father was 53, and his mother was 38 years old. He had an older brother, Sun Dezhang (Tôn đức chương), and an older sister, Sun Jin xing (Tôn sao Kim), who died at the early age of 4. Another older brother, Sun Deyou (Tôn đức hữu), died at the age of 6. He also had an older sister, Sun Miaoqian (Tôn diệu thiến), and a younger sister, Sun Qiuqi (Tôn thu khỉ).[30]

At age 20, Sun had anarranged marriagewith the fellow villagerLu Muzhen.She bore a son,Sun Fo,and two daughters, Sun Jinyuan (Tôn kim viện) and Sun Jinwan (Tôn kim uyển).[30]Sun Fo was the grandfather of Leland Sun, who spent 37 years working inHollywoodas an actor andstuntman.[152]Sun Yat-sen was also the godfather of Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, an American author and poet who wrote under the nameCordwainer Smith.

Sun's firstconcubine,the Hong Kong-bornChen Cuifen,lived inTaiping, Perak(now inMalaysia) for 17 years. The couple adopted a local girl as their daughter. Cuifen subsequently relocated to China, where she died.[153]

During Sun's exile in Japan, he had relationships with two Japanese women: the 15-year-oldHaru Asada,whom he took as a concubine up to her death in 1902, and another 15-year-old schoolgirl,Kaoru Otsuki,whom Sun married in 1905 and abandoned the next year while she was pregnant.[154]Otsuki later had their daughter, Fumiko, adopted by the Miyagawa family in Yokohama, who did not discover her parentage until 1951,[154]26 years after Sun's death.

On 25 October 1915 in Japan, Sun marriedSoong Ching-ling,one of theSoong sisters.[30][155]Soong Ching-ling's father was the American-educatedMethodistministerCharles Soong,who made a fortune in banking and in printing of Bibles. Although Charles had been a personal friend of Sun, he was enraged by Sun announcing his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian, hekept two wives:Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki. Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion.

Soong Ching-Ling's sister,Soong Mei-ling,later marriedChiang Kai-shek.

Cultural references

[edit]Memorials and structures in Asia

[edit]

In most majorChinese cities,one of the main streets isZhongshan Lu(Trung đường núi) to celebrate Sun's memory. There are also numerous parks, schools, and geographical features named after him. Xiangshan, Sun's hometown in Guangdong, was renamedZhongshanin his honor, and there is a hall dedicated to his memory at theTemple of Azure Cloudsin Beijing. There are also a series ofSun Yat-sen stamps.

Other references to Sun include theSun Yat-sen Universityin Guangzhou andNational Sun Yat-sen UniversityinKaohsiung.Other structures includeSun Yat-sen Mausoleum,Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall subway station,Sun Yat-sen housein Nanjing,Dr Sun Yat-sen Museumin Hong Kong,Chung-Shan Building,Sun Yat-sen Memorial HallinGuangzhou,Sun Yat-sen Memorial HallinTaipeiandSun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hallin Singapore.Zhongshan Memorial Middle Schoolhas also been a name used by many schools.Zhongshan Parkis also a common name used for a number of places named after him. The first highway in Taiwan is called theSun Yat-sen expressway.Two ships are also named after him; theChinese gunboat Chung Shanand theChinese cruiser Yat Sen.The old Chinatown inCalcutta(now known asKolkata), India, has the prominent Sun Yat-sen Street.

In Russia, a village inMikhaylovsky DistrictofPrimorsky Kraiwas namedSunyatsenskoein honor of him. There are streets named after him inAstrakhan,UfaandAldan.There was a street that was named after Sun in the Russian city ofOmskuntil 2005, when it was renamed in honor of the recipient of the titleHero of Soviet UnionMikhail Ivanovich Leonov.[156][157][158][159]

InGeorge Town,Penang,Malaysia,the Penang Philomatic Union had its premises at 120Armenian Streetin 1910, while Sun spent more than four months inPenangand convened the historic "Penang Conference" to launch the fundraising campaign for the Huanghuagang Uprising and founded theKwong Wah Yit Poh.The house, which has been preserved as theSun Yat-sen Museum(formerly called the Sun Yat Sen Penang Base), was visited by President-designateHu Jintaoin 2002. The Penang Philomatic Union subsequently moved to a bungalow at 65Macalister Road,which has been preserved as the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Centre Penang.

As a dedication, the 1966Chinese Cultural Renaissancewas launched on Sun's birthday on 12 November.[160]

TheNanyangWan Qing Yuan in Singapore have since been preserved and renamed as theSun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.[72]A Sun Yat-sen heritage trail was also launched on 20 November 2010 in Penang.[161]

Sun's Hawaiian birth certificate, which claimed that he was not born in China but in the United States, was on public display at theAmerican Institute in TaiwanonUS Independence Dayon 4 July 2011.[162]

A street inMedan,Indonesia,is named "Jalan Sun Yat-Sen" in honor of him.[163]

A street named "Tôn Dật Tiên" (theSino-Vietnamesename for Sun Yat-Sen) is located inPhú Mỹ Hưng Urban Area,Ho Chi Minh City,Vietnam.

The "Trail of Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh"[164]was established in 2019, based on the book "Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh."[165]

Gallery

[edit]-

Sun Yat-sen Memorial Centre,George Town,Penang, Malaysia.

-

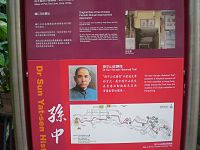

A marker on theSun Yat-sen Historical TrailonHong Kong Island.

-

Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall atTemple of Azure CloudsinBeijing,China.

-

Coffin (unused) for Sun Yat-sen, gifted by theСССР,inTemple of Azure Clouds.

-

Bronze statue in the Kang Le Yuan Garden at the South Guangzhou Campus ofSun Yat-sen University.Originally presented byUmeya ShokichiatGuangzhouNational Sun Yat-sen University Shipai Campus, which is now home to theSouth China University of Technology.

-

The Museum of Dr. Sun Yat-sen inCuiheng

Memorials and structures outside Asia

[edit]

St. John's University,inNew York City,has a facility built in 1973, the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall, which built to resemble a traditional Chinese building in honor of Sun.[166]Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden,located inVancouver,is the largest classical Chinese gardens outside Asia. The Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park is inChinatown, Honolulu.[167]On the island ofMaui,the little Sun Yat-sen Park at Kamaole is near where his older brother had a ranch on the slopes ofHaleakalain theKularegion.[17][18][19][50]

InLos Angeles,there is a seated statue of him in Central Plaza.[168]InSacramento,California, there is a bronze statue of Sun in front of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Sacramento. Another statue of Sun, byJoe Rosenthal,can be found atRiverdale Parkin Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and there is another statue in Toronto's downtownChinatown.There is also theMoscow Sun Yat-sen University.InChinatown, San Franciscois a 12-footstatue of SunonSaint Mary's Square.[169]

In late 2011, the Chinese Youth Society ofMelbourne,in celebration of the100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of China,unveiled in alion danceblessing ceremony amemorial statue of Sunoutside theChinese Museumin thecity's Chinatownon the spot that its traditionalChinese New Yearlion dance always ends.[170]

In 1993,Lily Sun,one of Sun Yat-sen's granddaughters, donated books, photographs, artwork and other memorabilia to theKapiʻolani Community Collegelibrary as part of the Sun Yat-sen Asian Collection.[171]During October and November every year the entire collection is shown.[171]In 1997, the Dr Sun Yat-sen Hawaii Foundation was formed online as a virtual library.[171]In 2006, theNASAMars Exploration RoverSpiritcalled one of the hills that was explored "Zhongshan."[172]

In 2019, astatue of Dr. Sun Yat-senby Lu Chun-Hsiung and Michael Kang was permanently installed in the northern plaza of Manhattan'sColumbus Park.[173][174]

In popular culture

[edit]Opera

[edit]Dr. Sun Yat-sen[175](Trung sơn dật tiên;ZhōngShān yì xiān) is a 2011Chinese-language western-style operain three acts by the New York-based American composerHuang Ruo,who was born in China and is a graduate ofOberlin College's Conservatory as well as the Juilliard School. The libretto was written byCandace Mui-ngam Chong,a recent collaborator with playwrightDavid Henry Hwang.[176]It was performed in Hong Kong in October 2011 and was given itsNorth Americapremiere on 26 July 2014 at theSanta Fe Opera.

Television series and films

[edit]Sun Yat-sen's life is portrayed in various films, mainlyThe Soong SistersandRoad to Dawn.A fictionalized assassination attempt on his life was featured inBodyguards and Assassins.He is also portrayed during his struggle to overthrow the Qing dynasty inOnce Upon a Time in China II.The television seriesTowards the RepublicfeaturesMa Shaohuaas Sun. In1911,a film commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution,Winston Chaoplayed Sun.[177]InSpace: Above and Beyond,one of the starships of the China Navy is named theSun Yat-sen.[178]

Performances

[edit]In 2010, the theatrical playYellow Flower on Slopes(Đường tà đạo hoa cúc) was created and performed.[179]

In 2011, theMandopopgroup Zhongsan Road 100 (Trung đường núi 100 hào) was known for singing the song "Our Father of the Nation" (Chúng ta quốc phụ).[180]

Works

[edit]- Kidnapped in London(1897)

- The Outline of National Reconstruction/Chien Kuo Ta Kang(1918)

- The Fundamentals of National Reconstruction/Jianguo fanglue(1924)

- The Principle of Nationalism(1953)

See also

[edit]- Chiang Kai-shek

- Chiang Ching-kuo

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Sun Yat-sen Museum Penang

- United States Constitution and worldwide influence

- Zhongshan suit

- Kuomintang

- Three Principles of the People

Notes

[edit]- ^Usually known asSun Zhongshan(traditional Chinese:Tôn Trung Sơn;simplified Chinese:Tôn Trung Sơn) in Chinese; also known byseveral other names.

- ^Contrary to a popular legend, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily although he was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him and to return his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ ofhabeas corpusbecause of the Legation'sdiplomatic immunity,but he began a campaign throughThe Times.Through diplomatic channels, theBritish Foreign Officepersuaded the Legation to release Sun.[52]

References

[edit]- ^

- "Sun Yat-sen".Collins English Dictionary.2020.

- "Sun Yat-sen".Dictionary.2023.

- ^Steinberg, Jessica (10 February 2021)."China's century-old support for Zionism surfaces in letter".The Times of Israel.Retrieved11 August2022.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoSingtaodaily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010.Đặc biệt kế hoạchsection A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary editionDân quốc chi phụ.

- ^abc"Chronology of Dr. Sun Yat-sen".Taipei: [[Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall (Taipei)|]]. Archived fromthe originalon 16 April 2014.Retrieved12 March2014.

- ^abcTung, William L. (1968).The political institutions of modern China.Springer publishing.ISBN978-9024705528.pp. 92, 106.

- ^Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (2 September 2016)."What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death".Chinese Journal of Cancer.35(1): 81.doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9.PMC5009495.PMID27586157.

- ^"Three Principles of the People".Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Schoppa, R. Keith (2000).The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History.Columbia University Press. p. 73, 165, 186.ISBN978-0-231-50037-1.

- ^Sun, Yat-sen (3 August 1924).Chủ nghĩa Tam Dân: Chủ nghĩa dân sinh đệ nhất giảng[Three Principles of the People: People's living, Lecture 1].Quốc phụ toàn tập[Complete collection of the National Father's scripts] (in Chinese). pp. 129–145. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2019.Retrieved30 December2019– via trung sơn học thuật cơ sở dữ liệu hệ thống.Chúng ta quốc dân đảng đề xướng chủ nghĩa dân sinh, đã có hơn hai mươi năm, không nói xã hội chủ nghĩa, chỉ nói chủ nghĩa dân sinh. Xã hội chủ nghĩa cùng chủ nghĩa dân sinh phạm vi là cái gì quan hệ đâu? Gần đây nước Mỹ có một vị Marx tín đồ William thị, miệt mài theo đuổi Marx chủ nghĩa, thấy được chính mình đồng môn cho nhau phân tranh, nhất định là Marx học thuyết còn có không nguyên vẹn địa phương, cho nên hắn liền phát biểu ý kiến, nói Marx lấy vật chất vì lịch sử trọng tâm là không đúng, xã hội vấn đề mới là lịch sử trọng tâm; mà xã hội vấn đề trung lại lấy sinh tồn làm trọng tâm, kia mới là hợp lý. Dân sinh vấn đề chính là sinh tồn vấn đề......

- ^abWang, Ermin ( vương ngươi mẫn ) (2011).Tư tưởng sáng tạo thời đại: Tôn Trung Sơn cùng Trung Hoa dân quốc.Showwe Information Co., Ltd. p. 274.ISBN978-9862217078.

- ^Wang, Shounan ( vương thọ nam ) (2007).Sun Zhong-san.Commercial PressTaiwan. p. 23.ISBN978-9570521566.

- ^abDu tử tường (2006).Lãnh tụ thanh âm: Hai bờ sông người lãnh đạo chính trị ngữ nghệ phê bình, 1906–2006.Wu-Nan Book Inc.p. 82.ISBN978-9571142685.

- ^Môn kiệt đan (4 December 2003).Nồng đậm hương tình hệ Trung Nguyên — phóng Tôn Trung Sơn tiên sinh cháu gái tôn tuệ phương tiến sĩ[Central Plains Nostalgia-Interview with Dr. Sun Suifang, granddaughter of Sun Yat-sen].China News(in Chinese).Archivedfrom the original on 8 July 2011.Translate this Chinese article to English

- ^Bohr, P. Richard (2009)."Did the Hakka Save China? Ethnicity, Identity, and Minority Status in China's Modern Transformation".Headwaters.26(3): 16.

- ^Sun Yat-sen.Stanford University Press. 1998. p.24.ISBN978-0804740111.

- ^abcdKubota, Gary (20 August 2017)."Students from China study Sun Yat-sen on Maui".Star-Advertiser.Honolulu.Retrieved21 August2017.

- ^abcdKHON web staff (3 June 2013)."Chinese government officials attend Sun Mei statue unveiling on Maui".KHON2.Honolulu.Archived fromthe originalon 22 August 2017.Retrieved21 August2017.

- ^abcd"Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park".Hawaii Guide.Retrieved21 August2017.

- ^abcd"Sun Yet Sen Park".County of Maui.Retrieved21 August2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^Gonschor, Lorenz (2 January 2017)."Revisiting the Hawaiian Influence on the Political Thought of Sun Yat-sen".The Journal of Pacific History.52(1): 52–67.doi:10.1080/00223344.2017.1319128.ISSN0022-3344.S2CID157738017.

- ^"Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882)".ʻIolani School.Archived fromthe originalon 20 July 2011.

- ^Brannon, John (16 August 2007)."Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen".Honolulu Star-Bulletin.Archived fromthe originalon 4 October 2012.Retrieved17 August2007.

Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College—now known as Punahou School—for one semester.

- ^Đạo Cơ Đốc cùng cận đại Trung Quốc cách mạng khởi nguyên: Lấy Tôn Trung Sơn vì lệ.Big5.chinanews:89. Archived fromthe originalon 28 October 2011.Retrieved26 September2011.

- ^"Central and Western Heritage Trail".Archived fromthe originalon 9 July 2021.Retrieved6 July2021.

- ^"The Diocesan Home and Orphanage".Sun Yat-sen Historic Trail.17 November 2017.Retrieved6 July2021.

- ^Trung sơn sử tích kính một ngày du.Lcsd.gov.hk. Archived fromthe originalon 2 November 2011.Retrieved26 September2011.

- ^"The Government Central School".Sun Yat-sen Historic Trail.14 January 2018.Retrieved6 July2021.

- ^abSun, Yat-sen. "The Imbroglio".Kidnapped in London.

- ^Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years.Hong Kong University Press. 2003.ISBN978-962-209-613-4.

- ^abcdSingtaoDaily.28 February 2011. Đặc biệt kế hoạch section A10. "Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition".

- ^South China Morning Post. "Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China". 11 November 1999.

- ^"...At present there are some seven members in the interior belonging to our mission, and two here, one I baptized last Sabbath, a young man who is attending the Government Central School. We had a very pleasant communion service yesterday..." – Hager to Clark, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.17, p.3

- ^"...We had a pleasant communion yesterday and received one Chinaman into the church..." – Hager to Pond, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.18, p.3 postscript

- ^Rev. C. R. Hager, 'The First Citizen of the Chinese Republic', The Medical Missionary v.22 1913, p.184

- ^Bergère:26

- ^abSoong, (1997) p. 151-178

- ^Trung Quốc và Phương Tây kẻ hèn hội nghị [Central & Western District Council] (November 2006),Tôn Trung Sơn tiên sinh sử tích kính[Dr Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail](PDF),Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum(in Chinese and English), Hong Kong, China, p. 30, archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 February 2012,retrieved15 September2012

- ^Bard, Solomon.Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918.(2002). HK University Press.ISBN978-9622095748.p. 183.

- ^abCurthoys, Ann; Lake, Marilyn (2005).Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective.ANU publishing.ISBN978-1920942441.p. 101.

- ^Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. (1994).Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen.Hoover press.ISBN978-0817992811.

- ^abVương hằng vĩ (2006).#5 thanh[Chapter 5. Qing dynasty].Trung Quốc lịch sử giảng đường.Trung Hoa thư cục. p. 146.ISBN9628885286.

- ^Bergère:39–40

- ^Bergère:40–41

- ^Yang, Zhiyi (2023).Poetry, History, Memory: Wang Jingwei and China in Dark Times.Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. p. 31.doi:10.3998/mpub.12697845.ISBN978-0-472-07650-5.OCLC1404445939,1417484741.

- ^ab(Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (2010).Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member.Bookoola. p. 17.ISBN978-9881804167

- ^Faure, David (1997).Society.Hong Kong University Press.ISBN978-9622093935.,founderTse Tsan-tai's account

- ^abcJoão de Pina-Cabral. (2002).Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao.Berg publishing.ISBN978-0-8264-5749-3.p. 209.

- ^abcBevir, Mark (2010).Encyclopedia of Political Theory.Sage publishing.ISBN978-1412958653.p 168.

- ^Lin, Xiaoqing Diana. (2006). Peking University:Chinese Scholarship And Intellectuals, 1898–1937.SUNY Press,ISBN978-0791463222.p. 27.

- ^abPaul Wood (November–December 2011)."The Other Maui Sun".Wailuku, Hawaii:Maui Nō Ka ʻOi Magazine.Retrieved2 February2017.

- ^"Sun Yat-sen | Chinese leader".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved31 March2018.

- ^Wong, J.Y. (1986).The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896–1987.Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

as summarized in

Clark, David J.; Gerald McCoy (2000).The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 162.ISBN978-0198265849. - ^Cantlie, James (1913).Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China.London: Jarrold & Sons.

- ^"JapanFocus".Old.japanfocus.org. Archived fromthe originalon 16 March 2012.Retrieved26 September2011.

- ^Thornber, Karen Laura. (2009).Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature.Harvard University Press. p. 404.

- ^Ocampo, Ambeth (2010).Looking Back 2.Pasig: Anvil Publishing. pp. 8–11.

- ^Gao, James Zheng. (2009).Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949).Scarecrow Press.ISBN978-0810849303.Chronology section.

- ^Bergère:86

- ^Lưu Sùng lăng (2004).Nhật Bản cận đại văn học tinh đọc.Năm nam sách báo xuất bản cổ phần công ty hữu hạn. p. 71.ISBN978-9571136752.

- ^Frédéric, Louis. (2005).Japan Encyclopedia.Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0674017535.p. 651.

- ^33 năm hoa rơi mộngTaiwan Ebook,National Central Library

- ^Eiji Murashima."The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand"(PDF).Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 March 2017.Retrieved30 March2017.

- ^Eric Lim."Soi Sun Yat Sen the legacy of a revolutionary".Tour Bangkok Legacies.Retrieved30 March2017.

- ^abcTôn Trung Sơn tư tưởng 3 học giả diễn thuyết xuất sắc.World journal.4 March 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2013.Retrieved26 September2011.

- ^"Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii".San Francisco, CA, US:Scribd.Retrieved15 September2012.

- ^abSmyser, A.A. (2000).Sun Yat-sen's strong links to Hawaii.Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."

- ^Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office."Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925"(PDF).Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004 ].Washington, DC, US:National Archives and Records Administration.pp. 92–152.Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925at theNational Archives and Records Administration.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 October 2013.Retrieved15 September2012.Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun was born inKula,a district ofMaui,Hawaii.

- ^abcdKế thu phong, chu khánh bảo. (2001). Trung Quốc cận đại sử, Volume 1. Chinese University Press.ISBN978-9622019874.p. 468.

- ^"Internal Threats – The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) – Imperial China – History – China – Asia".Countriesquest.Retrieved26 September2011.

- ^Streets of George Town, Penang.Areca Books. 2007. pp.34–.ISBN978-9839886009.

- ^abcdefghijklmYan, Qinghuang. (2008).The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions.World Scientific publishing.ISBN978-9812790477.pp. 182–187.

- ^ab"Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall".Wanqingyuan.org.sg. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2013.Retrieved7 May2015.

- ^"United Chinese Library".Roots.National Heritage Board. Archived fromthe originalon 3 December 2019.Retrieved15 September2019.

- ^abcKhoo, Salma Nasution. (2008).Sun Yat Sen in Penang.Areca publishing.ISBN978-9834283483.

- ^Tang Jiaxuan (2011).Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze: A Memoir of China's Diplomacy.HarperCollins publishing.ISBN978-0062067258.

- ^Nanyang Zonghui bao. The Union Times paper. 11 November 1909 p2.

- ^abcBergère:188

- ^Chan, Sue Meng (2013).Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh. Singapore.Singapore: Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall. p. 17.ISBN978-9810782092.

- ^Khoo & Lubis, Salma Nassution & Abdur-Razzaq (2005).Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development.Areca Books. p. 231.

- ^abVương hằng vĩ. (2005) (2006) Trung Quốc lịch sử giảng đường No. 5 thanh. Trung Hoa thư cục.ISBN9628885286.pp. 195–198.

- ^Bronze Relief of the 1911 Guangzhou ( Quảng Châu ) Uprising in Taipei Revolutionary Martyrs’ Shrine (YouTube)

- ^Carol, Steven. (2009).Encyclopedia of Days: Start the Day with History.iUniverse publishing.ISBN978-0595482368.

- ^Bergère:210

- ^Lane, Roger deWardt. (2008).Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins.ISBN978-0615244792.

- ^abWelland, Sasah Su-ling. (2007).A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters.Rowman Littlefield Publishing.ISBN978-0742553149.p. 87.

- ^abcdFu, Zhengyuan. (1993).Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics(Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0521442282). pp. 153–154.

- ^Bergère:226

- ^abcdCh'ien Tuan-sheng.The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949.Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0804705516.pp. 83–91.

- ^Ernest Young, "Politics in the Aftermath of Revolution", in John King Fairbank, ed.,The Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912–1949,Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983;ISBN978-0521235419), p. 228.

- ^Altman, Albert A., and Harold Z. Schiffrin. "Sun Yat-Sen and the Japanese: 1914–16." Modern Asian Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1972, pp. 385–400. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/311539

- ^South China Morning post.Sun Yat-sen's durable and malleable legacy. 26 April 2011.

- ^Thampi, Madhavi.India and China in the Colonial World.Taylor & Francis. p. 229.

- ^South China morning post. 1913–1922. 9 November 2003.

- ^abBergère & Lloyd:273

- ^Kirby, William C. [2000] (2000).State and economy in republican China: a handbook for scholars,volume 1. Harvard publishing.ISBN978-0674003682.p. 59.

- ^Crean, Jeffrey (2024).The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History.New Approaches to International History series. London, UK:Bloomsbury Academic.ISBN978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^Robert Payne (2008).Mao Tse-tung: Ruler of Red China.Read Books. p. 22.ISBN978-1443725217.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Ross, Harold Wallace; White, Katharine Sergeant Angell (1980).Great Soviet Encyclopedia.p. 237.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982).Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25.Macmillan.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Bernice A Verbyla (2010).Aunt Mae's China.Xulon Press. p. 170.ISBN978-1609574567.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^M.N. Roy's Mission to China.University of California Press. pp. 19–20.

- ^Gao. James Zheng. (2009).Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949).Scarecrow press.ISBN978-0810849303.p. 251.

- ^Spence, Jonathan D.[1990] (1990).The search for modern China.WW Norton & company publishing.ISBN978-0-393-30780-1.p. 345.

- ^Ji, Zhaojin. (2003).A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism.M.E. Sharpe Publishing.ISBN978-0765610034.p. 165.

- ^Ho, Virgil K.Y. (2005).Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period.Oxford University Press.ISBN0199282714

- ^Carroll, John Mark.Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong.Harvard University Press.ISBN0674017013

- ^Ma Yuxin (2010).Women journalists and feminism in China, 1898–1937.Cambria Press.ISBN978-1604976601.p. 156.

- ^Mã phúc tường, lâm hạ hồi tộc châu tự trị mã phúc tường, mã phúc tường giới thiệu – đi khắp Trung Quốc.elycn.Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2013.Retrieved23 June2017.

- ^Calder, Kent; Ye, Min (2010).The Making of Northeast Asia.Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0804769228.

- ^abcBarth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (1 January 2016)."What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death".Chinese Journal of Cancer.35(1): 81.doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9.ISSN1944-446X.PMC5009495.PMID27586157.

- ^ab"Dr. Sun Yat-sen Dies in Peking".The New York Times.12 March 1925.Retrieved28 December2017.

- ^"Lost Leader".Time.23 March 1925. Archived fromthe originalon 4 May 2008.Retrieved3 August2008.

A year ago his death was prematurely announced; but it was not until last January that he was taken to the Rockefeller Hospital at Peking and declared to be in the advanced stages of cancer of the liver.

- ^Sharman, L. (1968) [1934].Sun Yat-sen: His life and times.Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 305–306, 310.

- ^Quốc phụ di chúc[Founding Father's Will].Vincent's Calligraphy.Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^Bullock, M.B. (2011).The oil prince's legacy: Rockefeller philanthropy in China.Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 81.ISBN978-0804776882.

- ^Leinwand, Gerald (2002).1927: High Tide of the 1920s.Basic Books. p. 101.ISBN978-1568582450.Retrieved29 December2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ab"The Sydney Morning Herald. Sun Yat-Sen's Coffin. Soviet's Tawdry Gift".National Library of Australia.25 April 1925.Retrieved6 July2023.

- ^"Clinical record copies from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital decrypt the real cause of death of Sun Yat-sen".Nanfang Daily(in Chinese). 11 November 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 7 November 2017.Retrieved28 December2017.

- ^"Nàng là Trung Hoa dân quốc quốc phụ thê tử nhưng là toàn lực duy trì Trung Quốc Đảng Cộng Sản -- đăng báo / sinh hoạt".

- ^Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002).Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51.ISBN0742511448.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006).Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication.Taylor & Francis. pp. 134, 375.ISBN978-0415368353.Retrieved28 June2010.

- ^"KMT Divided Over God-Status of Founder Sun Yat-sen".The News Lens.28 April 2021.

- ^Rosecrance, Richard N. Stein, Arthur A. (2006).No more states?: globalization, national self-determination, and terrorism.Rowman & Littlefield publishing.ISBN978-0742539440.p. 269.

- ^Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung: Volume 5, Volume 5.2014. p. 333.

- ^Dimitrakis, Panagiotis (2017).The Secret War for China: Espionage, Revolution and the Rise of Mao.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 4.

- ^abShan, Patrick Fuliang (2024). "What Did the CCP Learn from the Past?". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.).China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment.Leiden University Press.p. 41.ISBN9789087284411.

- ^Mao, Zedong."On New Democracy".marxists.org.Retrieved7 May2022.

- ^.(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

- ^abcdKenneth Tan (3 October 2011)."Granddaughter of Sun Yat-Sen accuses China of distorting his legacy".Shanghaiist. Archived fromthe originalon 11 October 2011.Retrieved8 October2011.

- ^Quốc phụ cháu gái oanh trung cộng vặn vẹo chủ nghĩa Tam Dân ngu dân _ nhiều duy tân nghe võng(in Chinese). China.dwnews. 1 October 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 7 October 2011.Retrieved8 October2011.

- ^ab"Is Sun Yat-sen the 'founding father'?".Taipei Times.29 February 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 29 December 2019.Retrieved9 November2022.

- ^abNhân dân võng — Tôn Trung Sơn tao nhục mạ "Đài độc" tưởng làm "Đài Loan quốc phụ".People's Daily.Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2013.Retrieved12 October2011.

- ^abChiu Hei-yuan (5 October 2011)."History should be based on facts".Taipei Times.p. 8.

- ^Lu, P.C.; Brown, J.R. (2023).Ways of Confucius and of Christ: From Prime Minister of China to Benedictine Monk.Ignatius Press.ISBN978-1-64229-279-4.Retrieved29 July2024.

- ^Doyle, G. Wright (10 October 1911)."Sun Yat-sen".BDCC.Retrieved29 July2024.

- ^Ruokanen, M.; Huang, P.; Huang, B. (2010).Christianity and Chinese Culture.Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 93.ISBN978-0-8028-6556-4.Retrieved29 July2024.

- ^Schiffrin, H. (2023).Sun Yat-Sen and the Origins of the Chinese Revolution.University of California Press. p. 14.ISBN978-0-520-35101-1.Retrieved29 July2024.

- ^Lorenz Gonschor, "Revisiting the Hawaiian Influence on the Political Thought of Sun Yat-sen."Journal of Pacific History52.1 (2017): 52–67.

- ^Eric Helleiner, "Sun Yat-sen as a Pioneer of International Development."History of Political Economy50.S1 (2018): 76–93.

- ^Stephen Shen, and Robert Payne,Sun Yat-Sen: A Portrait(1946) p 182

- ^Unger, Jonathan (2015).Using the Past to Serve the Present: Historiography and Politics in Contemporary China.Routledge. p. 248.

- ^Godley, Michael R. (1987)."Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: Sun Yatsen and the International Development of China".The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs.18(18): 109–125.doi:10.2307/2158585.JSTOR2158585.S2CID155947428.

- ^The Far East in the Modern World.Dryden Press. 1975. p. 384.

- ^Westad, Odd Arne (2012).Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750.Random House. p. 155.

- ^France-Malone, Derek (2011).Political Dissent: A Global Reader: Modern Sources.Le xing ton Books. p. 175.

- ^Sun Yat-sen.Stanford University Press. 1998. p. 168.

- ^Peng, Chun (2018).Rural Land Takings Law in Modern China: Origin and Evolution.Cambridge University Press. p. 135.

- ^abcdRodriguez, Sarah Mellors (2023).Reproductive realities in modern China: birth control and abortion, 1911-2021.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1009027335.OCLC1366057905.

- ^Pan-Asianism A Documentary History, 1920–Present.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2011. p. 78.

- ^Pan-Asianism A Documentary History, 1920–Present.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2011. p. 85.

- ^Tôn Trung Sơn học thuật nghiên cứu tin tức võng – quốc phụ gia thế cùng cầu học[Dr. Sun Yat-sen's family background and schooling].[sun.yatsen.gov.tw/ sun.yatsen.gov.tw](in Chinese). 16 November 2005. Archived fromthe originalon 24 September 2011.Retrieved2 October2011.

- ^"Sun Yat-sen's descendant wants to see unified China".News.xinhuanet. 11 September 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 30 October 2014.Retrieved2 October2011.

- ^"Antong Cafe, The Oldest Coffee Mill in Malaysia".Archived fromthe originalon 12 January 2018.Retrieved12 January2018.

- ^abCorrespondent, Our."Japan-Revolution".asiasentinel.Retrieved31 January2022.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^Isaac F. Marcosson, Turbulent Years (1938), p.249

- ^"Россия, Астраханская область, Астрахань, улица Сун Ят-Сена".mapdata.ru.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^"Россия, Башкортостан, Уфа, улица Сун-Ят-Сена".mapdata.ru.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^"Россия, Якутия, Алданский улус, Алдан, улица Сунь-ят-Сена".mapdata.ru.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^"ЮБИЛЕЙНЫЕ ПЕРЕИМЕНОВАНИЯ".omsknews.ru.16 May 2005.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^Guy, Nancy. (2005).Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan.University of Illinois Press.ISBN0252029739.p. 67.

- ^"Sun Yet Sen Penang Base – News 17".Sunyatsenpenang. 19 November 2010.Retrieved2 October2011.[dead link]

- ^"Sun Yat-sen's US birth certificate to be shown".Taipei Times.2 October 2011. p. 3.Retrieved8 October2011.

- ^"Google Maps".Retrieved6 December2015.

- ^Kaur, Manjit (2 January 2020). "On the trail of Sun Yat Sen and comrades".The Star.

- ^Chan, Sue Meng (2013).Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh.Singapore: Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.ISBN978-9810782092.

- ^"Queens Campus".youvisit.Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2017.Retrieved23 June2017.

- ^"City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen".The City and County of Honolulu. 12 November 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 27 October 2011.Retrieved9 April2010.

- ^"Sun Yat-sen".Archived fromthe originalon 20 October 2017.Retrieved6 December2015.

- ^"St. Mary's Square in San Francisco Chinatown – The largest chinatown outside of Asia".Retrieved6 December2015.

- ^"Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne".cysm.org.Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne. Archived fromthe originalon 29 July 2012.Retrieved23 January2012.

- ^abc"Char Asian-Pacific Study Room".Library.kcc.hawaii.edu. 23 June 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 2 April 2012.Retrieved26 September2011.