Taishō era

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(April 2014) |

| TaishōĐại chính | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 July 1912 – 25 December 1926 | |||

Emperor Taishō (1900) | |||

| Location | Japan | ||

| Including | |||

| Monarch(s) | Taishō | ||

Chronology

| |||

| Part ofa serieson the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

TheTaishō era(Đại chính thời đại,Taishō jidai,[taiɕoːdʑidai])was a period in thehistory of Japandating from 30 July 1912 to 25 December 1926, coinciding with the reign ofEmperor Taishō.[1]The new emperor was a sickly man, which prompted the shift in political power from the oldoligarchicgroup of elder statesmen (orgenrō) to theImperial Diet of Japanand thedemocraticparties.Thus, the era is considered the time of theliberalmovement known asTaishō Democracy;it is usually distinguished from the preceding chaoticMeiji eraand the followingmilitaristic-driven first part of theShōwa era.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The two kanji characters in Taishō (Đại chính) were from a passage of theClassical ChineseI Ching:Trùm lấy chính thiên chi đạo cũng(Translated: "Great prevalence is achieved through rectitude, and this is theDaoof Heaven. ")[3]The term could be roughly understood as meaning "great rectitude", or "great righteousness".

Meiji legacy

[edit]

On 30 July 1912,Emperor Meijidied and Crown PrinceYoshihitosucceeded to the throne asEmperor of Japan.In his coronation address, the newly enthroned Emperor announced his reign'snengō(era name)Taishō,meaning "great righteousness".[4]

The end of the Meiji period was marked by huge government, domestic, and overseas investments and defense programs, nearly exhausted credit, and a lack of foreign reserves to pay debts. The influence ofWestern cultureexperienced in the Meiji period also continued. Notable artists, such asKobayashi Kiyochika,adopted Western painting styles while continuing to work inukiyo-e;others, such asOkakura Kakuzō,kept an interest in traditionalJapanese painting.Authors such asMori Ōgaistudied in the West, bringing back with them to Japan different insights on human life influenced by developments in the West.

The events following theMeiji Restorationin 1868 had seen not only the fulfillment of many domestic and foreign economic and political objectives—without Japan suffering the colonial fate of other Asian nations—but also a new intellectual ferment, in a time when there was worldwide interest in communism and socialism and an urbanproletariatwas developing. Universal malesuffrage,social welfare,workers' rights,and nonviolent protests were ideals of the early leftist movement.[citation needed]Government suppression of leftist activities, however, led to more radical leftist action and even more suppression, resulting in the dissolution of theJapan Socialist Party(Nhật Bản xã hội đảng,Nihon Shakaitō)only a year after its founding and general failure of the socialist movement in 1906.[citation needed]

The beginning of the Taishō period was marked by theTaishō political crisisin 1912–13 that interrupted the earlier politics of compromise. WhenSaionji Kinmochitried to cut the military budget, the army minister resigned, bringing down theRikken Seiyūkaicabinet. BothYamagata Aritomoand Saionji refused to resume office, and thegenrōwere unable to find a solution. Public outrage over the military manipulation of the cabinet and the recall ofKatsura Tarōfor a third term led to still more demands for an end togenrōpolitics. Despite old guard opposition, the conservative forces formed a party of their own in 1913, theRikken Dōshikai,a party that won a majority in the House over the Seiyūkai in late 1914.

On February 12, 1913,Yamamoto Gonnohyōesucceeded Katsura asprime minister.In April 1914,Ōkuma Shigenobureplaced Yamamoto.

Crown Prince Yoshihito marriedSadako Kujōon 10 May 1900. Their coronation took place on November 11, 1915.

World War I and hegemony in China

[edit]

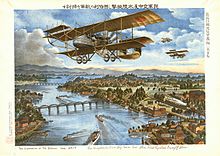

World War Ipermitted Japan, which fought on the side of the victoriousAllied Powers,to expand its influence in Asia and its territorial holdings in the north equatorial Pacific. Japan declared war on Germany on August 23, 1914, and quickly occupied German-leased territories in China'sShandongand theMariana,Caroline,andMarshallislands in the north Pacific Ocean. On November 7,Jiaozhousurrendered to Japan.

With its Western allies heavily involved in the war in Europe, Japan sought further to consolidate its position in China by presenting theTwenty-One Demands(Japanese:Đối hoa 21 ヶ điều yêu cầu;Chinese:21 điều) to theGovernmentin January 1915. Besides expanding its control over German holdings,ManchuriaandInner Mongolia,Japan also sought joint ownership of a major mining and metallurgical complex in central China, prohibitions on China's ceding or leasing any coastal areas to a third power, and miscellaneous other political, economic and military controls, which, if achieved, would have reduced China to a Japanese protectorate. In the face of slow negotiations with the Chinese government, widespreadanti-Japanese sentiment in Chinaand international condemnation forced Japan to withdraw the final group of demands and treaties were signed in May of 1915.

Japan's hegemony in northern China and other parts of Asia was facilitated through other international agreements. One with Russia in 1916 helped further secure Japan's influence in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, and agreements with France, Britain, and the United States in 1917 recognized Japan's territorial gains in China and the north Pacific. TheNishihara Loans(named after Nishihara Kamezo, Tokyo's representative in Beijing) of 1917 and 1918, while aiding the Chinese government, put China still deeper into Japan's debt. Toward the end of the war, Japan increasingly filled orders for its European allies' needed war material, thus helping to diversify the country's industry, increase its exports, and transform Japan from a debtor to a creditor nation for the first time.

Japan's power in Asia grew following the collapse of the Imperial Russian government in 1917 after theRussian Revolution.Wanting to seize the opportunity, the Japanese army planned to occupySiberiaas far west asLake Baikal.To do so, Japan had to negotiate an agreement with China allowing the transit of Japanese troops through Chinese territory. Although the force was scaled back to avoid antagonizing the United States, more than 70,000 Japanese troops joined the much smaller units of theAllied expeditionary forcesent to Siberia in July 1918 as part of theAllied intervention in the Russian Civil War.

On October 9, 1916,Terauchi Masataketook over asprime ministerfromŌkuma Shigenobu.On November 2, 1917, theLansing–Ishii Agreementnoted the recognition of Japan's interests in China and pledges of keeping an "Open Door Policy"(Môn hộ mở ra chính sách).From July to September 1918,rice riotserupted due to increasing price of rice. The large scale rioting and collapse of public order led to the end of Terauchi Masatake government.

Japan after World War I: Taishō Democracy

[edit]

The postwar era brought Japan unprecedented prosperity.[citation needed]Japan went to the1919 Paris Peace Conferenceas one of the great military and industrial powers of the world and received official recognition as one of the "Big Five" nations of the new international order.[5]Tokyo was granted a permanent seat on the Council of theLeague of Nationsand the peace treaty confirmed the transfer to Japan of Germany's rights inShandong,a provision that led to anti-Japanese riots and a mass political movement throughout China. Similarly, Germany's former north Pacific islands were put under aJapanese mandate.Japan was also involved in the post-war Allied intervention in Russia and was the last Allied power to withdraw (doing so in 1925). Despite its small role in World War I and the Western powers' rejection of itsbid for a racial equality clausein the peace treaty, Japan emerged as a major actor in international politics at the close of the war.

The two-party political system that had been developing in Japan since the turn of the century came of age after World War I, gave rise to the nickname for the period, "Taishō Democracy".In 1918,Hara Takashi,a protégé of Saionji and a major influence in the prewar Seiyūkai cabinets, had become the first commoner to serve as prime minister. He took advantage of long-standing relationships he had throughout the government, won the support of the survivinggenrōand the House of Peers, and brought into his cabinet as army ministerTanaka Giichi,who had a greater appreciation of favorable civil-military relations than his predecessors. Nevertheless, major problems confronted Hara: inflation, the need to adjust the Japanese economy to postwar circumstances, the influx of foreign ideas, and an emerging labor movement. Prewar solutions were applied by the cabinet to these postwar problems, and little was done to reform the government. Hara worked to ensure a Seiyūkai majority through time-tested methods, such as new election laws and electoral redistricting, and embarked on major government-funded public works programs.[6]

The public grew disillusioned with the growing national debt and the new election laws, which retained the old minimum tax qualifications for voters. Calls were raised for universal suffrage and the dismantling of the old political party network. Students, university professors, and journalists, bolstered by labor unions and inspired by a variety of democratic, socialist, communist, anarchist, and other Western schools of thought, mounted large but orderly public demonstrations in favor of universal male suffrage in 1919 and 1920.[citation needed]New elections brought still another Seiyūkai majority, but barely so. In the political milieu of the day, there was a proliferation of new parties, including socialist and communist parties.

In the midst of this political ferment, Hara was assassinated by a disenchanted railroad worker in 1921. Hara was followed by a succession of nonparty prime ministers and coalition cabinets. Fear of a broader electorate, left-wing power, and the growing social change engendered by the influx of Western popular culture together led to the passage of thePeace Preservation Lawin 1925, which forbade any change in the political structure or the abolition of private property.

In 1921, during theInterwar period,Japan developed and launched theHōshō,which was the first purpose-designedaircraft carrierin the world.[7][a]Japan subsequently developed a fleet of aircraft carriers that was second to none.

Unstable coalitions and divisiveness in the Diet led theKenseikai(Chính trị dân chủ sẽ,Constitutional Government Association)and theSeiyū Hontō(Chính hữu bổn đảng,TrueSeiyūkai)to merge as theRikken Minseitō(Lập hiến dân chính đảng,Constitutional Democratic Party)in 1927. TheRikken Minseitōplatform was committed to the parliamentary system, democratic politics, and world peace. Thereafter, until 1932, theSeiyūkaiand theRikken Minseitōalternated in power.

Despite the political realignments and hope for more orderly government, domestic economic crises plagued whichever party held power. Fiscal austerity programs and appeals for public support of such conservative government policies as the Peace Preservation Law—including reminders of the moral obligation to make sacrifices for the emperor and the state—were attempted as solutions. While the impact of theAmerican panic of October 1929was still reverberating throughout the world, the Japanese government lifted the gold embargo at the old parity in January 1930. These two blows struck the Japanese economy simultaneously, and the country was plunged into a severe depression.[8]There was a sense of rising discontent that was heightened with the assault uponRikken Minseitōprime ministerOsachi Hamaguchiin 1930. Though Hamaguchi survived the attack and tried to continue in office despite the severity of his wounds, he was forced to resign the following year and died not long afterwards.

Communism and socialism and the Japanese response

[edit]Thevictory of the Bolsheviks in Russiain 1922 and their hopes for aworld revolutionled to the establishment of theComintern.The Comintern realized the importance of Japan in achieving successful revolution in East Asia and actively worked to form theJapanese Communist Party,which was founded in July 1922. The announced goals of the Japanese Communist Party in 1923 included the unification of the working class as well as farmers, recognition of the Soviet Union, and withdrawal of Japanese troops from Siberia, Sakhalin, China, Korea, and Taiwan. In the coming years, authorities tried to suppress the party, especially after theToranomon Incidentwhen a radical student under the influence of Japanese Marxist thinkers tried to assassinate Prince RegentHirohito.The1925 Peace Preservation Lawwas a direct response to the perceived "dangerous thoughts" perpetrated by communist and socialist elements in Japan.

The liberalization of election laws with theGeneral Election Lawin 1925 benefited communist candidates, even though the Japan Communist Party itself was banned. A new Peace Preservation Law in 1928, however, further impeded communist efforts by banning the parties they had infiltrated. The police apparatus of the day was ubiquitous and quite thorough in attempting to control the socialist movement. By 1926, the Japan Communist Party had been forced underground, by the summer of 1929 the party leadership had been virtually destroyed, and by 1933 the party had largely disintegrated.

Pan-Asianismwas characteristic ofright-wing politicsand conservative militarism since the inception of the Meiji Restoration, contributing greatly to the pro-war politics of the 1870s. Disenchanted formersamuraihad established patriotic societies and intelligence-gathering organizations, such as theGen'yōsha(Huyền dương xã,"Black Ocean Society", founded in 1881)and its later offshoot, theKokuryūkai(Hắc long sẽ,"Black Dragon Society" or "Amur River Society", founded in 1901).These groups became active in domestic and foreign politics, helped foment pro-war sentiments, and supported ultra-nationalist causes through the end ofWorld War II.After Japan's victories over China and Russia, the ultra-nationalists concentrated on domestic issues and perceived domestic threats such as socialism and communism.

Taishō foreign policy

[edit]

Emerging Chinese nationalism, the victory of the communists in Russia, and the growing presence of the United States in East Asia all worked against Japan's postwar foreign policy interests. The four-yearSiberian expeditionand activities in China, combined with big domestic spending programs, had depleted Japan's wartime earnings. Only through more competitive business practices, supported by further economic development and industrial modernization, all accommodated by the growth of thezaibatsu,could Japan hope to become dominant in Asia. The United States, long a source of many imported goods and loans needed for development, was seen as becoming a major impediment to this goal because of its policies of containing Japanese imperialism.

An international turning point inmilitary diplomacywas theWashington Conference of 1921–22,which produced a series of agreements that effected a new order in the Pacific region. Japan's economic problems made a naval buildup nearly impossible and, realizing the need to compete with the United States on an economic rather than a military basis, rapprochement became inevitable. Japan adopted a more neutral attitude toward the civil war in China, dropped efforts to expand its hegemony intoChina proper,and joined the United States, Britain, and France in encouraging Chinese self-development.

In theFour-Power Treatyon Insular Possessions signed on December 13, 1921, Japan, the United States, Britain, and France agreed to recognize the status quo in the Pacific, and Japan and Britain agreed to formally terminate theAnglo-Japanese Alliance.TheWashington Naval Treaty,signed on February 6, 1922, established an international capital ship ratio for the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy (5, 5, 3, 1.75, and 1.75, respectively) and limited the size and armaments of capital ships already built or under construction. In a move that gave the Japanese Imperial Navy greater freedom in the Pacific Ocean, Washington and London agreed not to build any new military bases between Singapore and Hawaii.

The goal of theNine-Power Treatyalso signed on February 6, 1922, by Belgium, China, the Netherlands, and Portugal, along with the original five powers, was to prevent a war in the Pacific. The signatories agreed to respect China's independence and integrity, not to interfere in Chinese attempts to establish a stable government, to refrain from seeking special privileges in China or threatening the positions of other nations there, to support a policy of equal opportunity for commerce and industry of all nations in China, and to reexamine extraterritoriality and tariff autonomy. Japan also agreed to withdraw its troops fromShandong,relinquishing all but purely economic rights there, and to evacuate its troops from Siberia.

End of the Taishō Democracy

[edit]Overall, during the 1920s, Japan changed its direction toward a democratic system of government. However,parliamentary governmentwas not rooted deeply enough to withstand the economic and political pressures of the 1930s, during which military leaders became increasingly influential. These shifts in power were made possible by the ambiguity and imprecision of theMeiji Constitution,particularly regarding the position of the Emperor in relation to the constitution.[citation needed]

Timeline

[edit]- 1912: TheCrown Prince Yoshihitoassumes the throne because of his father,Emperor Meiji's death (July 30). GeneralKatsura Tarōbecomesprime ministerfor a third term (May 26).

- 1913: Katsura is forced to resign, and AdmiralYamamoto Gonnohyōebecomes prime minister (February 20).

- 1914:Ōkuma Shigenobubecomes prime minister for a second term (April 16). Japan declares war onGerman Empire,joining theAlliesside ofWorld War I(August 23).

- 1915: Japan sends theTwenty-One DemandstoChina(January 18).

- 1916:Terauchi Masatakebecomes prime minister (October 9).

- 1917:Lansing–Ishii Agreementgoes into effect (November 2).

- 1918-20:Spanish flupandemic began to devastate Japan, which killed 400,000 people.

- 1918:Siberian interventionlaunched (July).Hara Takashibecomes prime minister (September 29).

- 1919:March 1st Movementbegins againstJapanese colonial rule in Korea(March 1).

- 1920: Japan helps found theLeague of Nations.

- 1921: Prime Minister Hara is assassinated and he is succeeded byTakahashi Korekiyo(November 4).Crown Prince Hirohitobecomesregentbecause his father, Emperor Taishō has an illness (November 29).Four-Power Treatyis signed (December 13).

- 1922:Five Power Naval Disarmament Treatyis signed (February 6). AdmiralKatō Tomosaburōbecomes prime minister (June 12). Japan withdraws troops fromSiberia(August 28).

- 1923: TheGreat Kantō earthquakedevastatesTokyo(September 1). Yamamoto becomes prime minister for a second term (September 2).

- 1924:Kiyoura Keigobecomes prime minister (January 7). Crown Prince Hirohito (the future Emperor Shōwa) marries Princess Nagako of Kuni (the futureEmpress Kōjun) (January 26).Katō Takaakibecomes prime minister (June 11).

- 1925:General Election Lawwas passed, all men above age 25 gained the right to vote (May 5). Besides,Peace Preservation Lawis passed. Hirohito's first issue,Shigeko, Princess Teruis born (December 9).

- 1926:Wakatsuki Reijirōbecomes prime minister (30 January). Emperor Taishō dies; He is succeeded by his eldest son, Crown Prince Hirohito (December 25).

Equivalent calendars

[edit]By coincidence, Taishō year numbering just happens to be the same as that of theMinguo calendarof the Republic of China, and theJuche calendarofNorth Korea.

Conversion table

[edit]To convert anyGregorian calendaryear between 1912 and 1926 toJapanese calendaryear in Taishō era, subtract 1911 from the year in question.

| Taishō | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | XIII | XIV | XV | |

| AD | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 |

| MCMXII | MCMXIII | MCMXIV | MCMXV | MCMXVI | MCMXVII | MCMXVIII | MCMXIX | MCMXX | MCMXXI | MCMXXII | MCMXXIII | MCMXXIV | MCMXXV | MCMXXVI |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Nussbaum & Roth 2005,p.929atGoogle Books.

- ^Hoffman, Michael (July 29, 2012),"The Taisho Era: When modernity ruled Japan's masses",The Japan Times,p. 7.

- ^Lynn, Richard John (1994).The Classic of Changes.New York: Columbia University Press.ISBN0-231-08294-0.

- ^Bowman 2000,p. 149.

- ^Dower, John W(1999),Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II,New York: W. W. Norton & Co., p. 21.

- ^Hoffman, Michael, "'Taisho Democracy' pays the ultimate price",The Japan Times,July 29, 2012, p. 8

- ^Polmar, Norman (1 September 2006).Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events, Volume I: 1909-1945.Potomac Books, Inc. p. 35.ISBN978-1-57488-663-4.Retrieved4 September2023.

- ^Nakamura, T. (1997). "Depression, Recovery, and War, 1920–1945". In K. Yamamura (ed.).The Economic Emergence of Modern Japan.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–158.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511572814.004.ISBN9780521571173.

Bibliography

[edit]- Benesch, Oleg (December 2018)."Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan"(PDF).Transactions of the Royal Historical Society.28:107–134.doi:10.1017/S0080440118000063.ISSN0080-4401.S2CID158403519.

- Bowman, John Stewart (2000).Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture.New York: Columbia University Press.ISBN9780231500043.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.War and National Reinvention: Japan in the Great War, 1914–1919(Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1999).

- Duus, Peter, ed.The Cambridge History of Japan: The Twentieth Century(Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric; Roth, Käthe (2005),Japan Encyclopedia,Cambridge:Harvard University Press,ISBN978-0-674-01753-5,OCLC58053128.Louis-Frédéric is a pseudonym of Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum,seeAuthority File,Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, archived fromthe originalon May 24, 2012.

- Strachan, Hew.The First World War: Volume I: To Arms(Oxford University Press, 2003) 455–94.

- Takeuchi, Tatsuji (1935).War and Diplomacy in the Japanese Empireonline free

- Vogel, Ezra F. (2019).China and Japan: Facing Historyexcerpt

Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain."Japan".Country Studies.Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain."Japan".Country Studies.Federal Research Division.

External links

[edit]- Meiji Taisho 1868–1926(in Japanese)