Taoist meditation

| Taoist meditation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Đạo gia minh tưởng | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Tao school deep thinking | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part ofa serieson |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Taoist meditation(/ˈdaʊɪst/,/ˈtaʊ-/), also spelledDaoist(/ˈdaʊ-/), refers to the traditionalmeditativepractices associated with the Chinese philosophy and religion ofTaoism,including concentration, mindfulness, contemplation, and visualization. The earliest Chinese references to meditation date from theWarring States period(475–221 BCE).

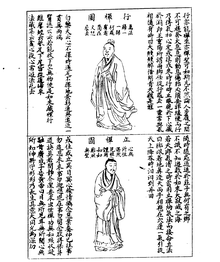

Traditional Chinese medicineandChinese martial artshave adapted certain Daoist meditative techniques. Some examples areDaoyin"guide and pull" breathing exercises,Neidan"internal alchemy" techniques,Neigong"internal skill" practices,Qigongbreathing exercises,Zhan zhuang"standing like a post" techniques. The opposite direction of adoption has also taken place, when the martial art ofTaijiquan,"great ultimate fist", became one of the practices of modern Daoist monks, while historically it was not among traditional techniques.

Terminology

[edit]

TheChinese languagehas several keywords for Daoist meditation practices, some of which are difficult to translate accurately into English.

Types of meditation

[edit]Livia Kohn distinguishes three basic types of Daoist meditation: "concentrative", "insight", and "visualization".[1]

DingĐịnhliterally means "decide; settle; stabilize; definite; firm; solid" and early scholars such asXuanzangused it to translateSanskritsamadhi"deep meditative contemplation" in ChineseBuddhist texts.In this sense, Kohn rendersdingas "intent contemplation" or "perfect absorption".[2]TheZuowanglunhas a section calledTaidingThái định"intense concentration"

GuanXembasically means "look at (carefully); watch; observe; view; scrutinize" (and names theYijingHexagram 20Guan"Viewing" ).Guanbecame the Daoist technical term for "monastery; abbey", exemplified byLouguanLâu xem"Tiered Abbey" temple, designating "Observation Tower", which was a major Daoist center from the 5th through 7th centuries (seeLouguantai). Kohn says the wordguan,"intimates the role of Daoist sacred sites as places of contact with celestial beings and observation of the stars".[3]Tang dynasty(618–907) Daoist masters developedguan"observation" meditation from Tiantai BuddhistzhiguanNgăn xem"cessation and insight" meditation, corresponding tośamatha-vipaśyanā– the two basic types of Buddhist meditation aresamatha"calm abiding; stabilizing meditation" andvipassanā"clear observation; analysis". Kohn explains, "The two words indicate the two basic forms of Buddhist meditation:zhiis a concentrative exercise that achieves one-pointedness of mind or "cessation" of all thoughts and mental activities, whileguanis a practice of open acceptance of sensory data, interpreted according to Buddhist doctrine as a form of "insight" or "wisdom".[4]Guanmeditators would seek to merge individual consciousness into emptiness and attain unity with the Dao.

CunTồnusually means "exist; be present; live; survive; remain", but has a sense of "to cause to exist; to make present" in the Daoist meditation technique, which both theShangqing SchoolandLingbao Schoolspopularized.

It thus means that the meditator, by an act of conscious concentration and focused intention, causes certain energies to be present in certain parts of the body or makes specific deities or scriptures appear before his or her mental eye. For this reason, the word is most commonly rendered "to visualize" or, as a noun, "visualization." Since, however, the basic meaning ofcunis not just to see or be aware of but to be actually present, the translation "to actualize" or "actualization" may at times be correct if somewhat alien to the Western reader.[5]

Other key words

[edit]Within the above three types of Daoist meditation, some important practices are:

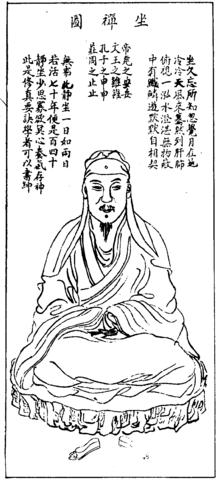

- ZuowangNgồi quên"sitting forgetting" was first recorded in the (c. 3rd century BCE)Zhuangzi.

- ShouyiThủ một"guarding the one; maintaining oneness" involvesding"concentrative meditation" on a single point or god within the body, and is associated with Daoist alchemical and longevity techniques.[6]The author, Dr. and MasterZhi Gang Shasaysshouyimeans meditational focus on thejindanKim Đana "golden light ball" in his own words.[7]

- NeiguanNội xem"inner observation; inner vision" is visualizing inside one's body and mind, includingzangfuorgans, inner deities,qimovements, and thought processes.

- YuanyouĐi xa"far-off journey; ecstatic excursion", best known as theChucipoem titleYuan You,was meditative travel to distant countries, sacred mountains, the sun and moon, and encounters with gods andxiantranscendents.

- ZuoboNgồi bát"sitting around the bowl (water clock) "was aQuanzhen Schoolcommunal meditation that was linked to Buddhistzuochan(Japanesezazen)Ngồi thiền"sitting meditation"

Warring States period

[edit]The earliest Chinese references to meditation date from theWarring States period(475–221 BCE), when the philosophicalHundred Schools of Thoughtflourished.

Guanzi and Neiye

[edit]Four chapters of theGuanzihave descriptions of meditation practices:XinshuRắp tâm"Mind techniques" (chapters 36 and 37),BaixinBạch tâm"Purifying the mind" (38), andNeiye"Inward training" (49). Modern scholars[8]believe theNeiyetext was written in the 4th century BCE, and the others were derived from it.A. C. Grahamregards theNeiyeas "possibly the oldest 'mystical' text in China";[9]Harold Roth describes it as "a manual on the theory and practice of meditation that contains the earliest references to breath control and the earliest discussion of the physiological basis of self-cultivation in the Chinese tradition".[10]Owing to the consensus that proto-DaoistHuang-Laophilosophers at theJixia AcademyinQicomposed the coreGuanzi,Neiyemeditation techniques are technically "Daoistic" rather than "Daoist".[11]

NeiyeVerse 8 associatesdingxinThảnh thơi"stabilizing the mind" with acute hearing and clear vision, and generatingjingTinh"vital essence". However, thought, says Roth, is considered "an impediment to attaining the well-ordered mind, particularly when it becomes excessive".[12]

If you can be aligned and be tranquil,

Only then can you be stable.

With a stable mind at your core,

With the eyes and ears acute and clear,

And with the four limbs firm and fixed,

You can thereby make a lodging place for the vital essence.

The vital essence: it is the essence of the vital energy.

When the vital energy is guided, it [the vital essence] is generated,

But when it is generated, there is thought,

When there is thought, there is knowledge,

But when there is knowledge, then you must stop.

Whenever the forms of the mind have excessive knowledge,

You lose your vitality.[13]

NeiyeVerse 18 contains the earliest Chinese reference to practicing breath-control meditation. Breathing is said to "coil and uncoil" or "contract and expand" ', "with coiling/contracting referring to exhalation and uncoiling/expanding to inhalation".[14]

For all [to practice] this Way:

You must coil, you must contract,

You must uncoil, you must expand,

You must be firm, you must be regular [in this practice].

Hold fast to this excellent [practice]; do not let go of it.

Chase away the excessive; abandon the trivial.

And when you reach its ultimate limit

You will return to the Way and its inner power. (18)[15]

NeiyeVerse 24 summarizes "inner cultivation" meditation in terms ofshouyiThủ một "maintaining the one" andyunqiVận khí"revolving theqi".Roth says this earliest extantshouyireference "appears to be a meditative technique in which the adept concentrates on nothing but the Way, or some representation of it.[16]It is to be undertaken when you are sitting in a calm and unmoving position, and it enables you to set aside the disturbances of perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and desires that normally fill your conscious mind. "

When you enlarge your mind and let go of it,

When you relax your vital breath and expand it,

When your body is calm and unmoving:

And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances.

You will see profit and not be enticed by it,

You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

In solitude you delight in your own person.

This is called "revolving the vital breath":

Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly. (24)[17]

Tao Te Ching

[edit]Several passages in the classicTao Te Chingare interpreted as referring to meditation. For instance, "Attain utmost emptiness, Maintain utter stillness" (16)[18]emphasizesxuHư"empty; void" andjingTĩnh"still; quiet", both of which are central meditative concepts. Randal P. Peerenboom describes Laozi's contemplative process as "apophaticmeditation ", the" emptying of all images (thoughts, feelings, and so on) rather than concentration on or filling the mind with images ", comparable with Buddhistnirodha-samapatti"cessation of feelings and perceptions" meditation.[19]

Verse 10 gives what Roth calls "probably the most important evidence for breathing meditation" in theTao Te Ching.[20]

While you

Cultivate the soul and embrace unity,

can you keep them from separating?

Focus your vital breath until it is supremely soft,

can you be like a baby?

Cleanse the mirror of mysteries,

can you make it free of blemish?

Love the people and enliven the state,

can you do so without cunning?

Open and close the gate of heaven,

can you play the part of the female?

Reach out with clarity in all directions,

can you refrain from action?

It gives birth to them and nurtures them,

It gives birth to them but does not possess them,

It rears them but does not control them.

This is called “mysterious integrity.”[21]

Three of theseTao Te Chingphrases resonate withNeiyemeditation vocabulary.BaoyiÔmMột "embrace unity" compares withshouyiThủ một"maintain the One" (24 above).[22]ZhuanqiChuyên khí"focus your vital breath" iszhuanqiĐoàn khí"concentrating your vital breath" (19).[23]Dichu xuan gianGột sạch huyền lãm"cleanse the mirror of mysteries" andjingchu qi sheKính trừ này xá"diligently clean out its lodging place" (13)[24]have the same verbchu"eliminate; remove".

TheTaodejingexists in two received versions, named after the commentaries. The "Heshang Gong version" (see below) explains textual references to Daoist meditation, but the "Wang Bi version" explains them away.Wang Bi(226–249) was a scholar ofXuanxue"mysterious studies; neo-Daoism", which adapted Confucianism to explain Daoism, and his version eventually became the standardTao Te Chinginterpretation.Richard Wilhelmsaid Wang Bi's commentary changed theTao Te Ching"from a compendiary of magical meditation to a collection of free philosophicalaperçus".[25]

Zhuangzi

[edit]The (c. 4th–3rd centuries BCE) DaoistZhuangzirefers to meditation in more specific terms than theTao Te Ching.Two well-known examples of mental disciplines areConfuciusand his favorite discipleYan HuidiscussingxinzhaiTâm trai"heart-mind fasting" andzuowang"sitting forgetting".[26]In the first dialogue, Confucius explainsxinzhai.

"I venture to ask what 'fasting of the mind' is," said Hui.

"Maintaining the unity of your will," said Confucius, "listen not with your ears but with your mind. Listen not with your mind but with your primal breath. The ears are limited to listening, the mind is limited to tallying. The primal breath, however, awaits things emptily. It is only through the Way that one can gather emptiness, and emptiness is the fasting of the mind." (4)[27]

In the second, Yan Hui explainszuowangmeditation.

Yen Hui saw Confucius again on another day and said, "I'm making progress."

"What do you mean?"

"I sit and forget."

"What do you mean, 'sit and forget'?" Confucius asked with surprise.

"I slough off my limbs and trunk," said Yen Hui, "dim my intelligence, depart from my form, leave knowledge behind, and become identical with the Transformational Thoroughfare. This is what I mean by 'sit and forget'."

"If you are identical," said Confucius, "then you have no preferences. If you are transformed, then you have no more constants. It's you who is really the worthy one! Please permit me to follow after you." (9)[28]

Roth interprets this "slough off my limbs and trunk" (Đọa tứ chi) phrase to mean, "lose visceral awareness of the emotions and desires, which for the early Daoists, have 'physiological' bases in the various organs".[29]Peerenboom further describeszuowangas "aphophatic or cessation meditation."

One does away with sense perceptions, with all forms of cognition (thoughts, knowledge, conceptions, idea, images), with all valuations (preferences, norms, mores). Cognate to and a variant ofwang(Quên—to forget) iswang(Vong—to destroy, perish, disappear, not exist). In the apophatic meditative process, all distinctions and ways of distinguishing are "forgotten" in the sense of eliminated: they cease to exist.[30]

AnotherZhuangzichapter describes breathing meditation that results in a body "like withered wood" and a mind "like dead ashes".

Sir Motley of Southurb sat leaning against his low table. He looked up to heaven and exhaled slowly. Disembodied, he seemed bereft of soul. Sir Wanderer of Countenance Complete, who stood in attendance before him, asked, "How can we explain this? Can the body really be made to become like withered wood? Can the mind really be made to become like dead ashes? The one who is leaning against the table now is not the one who was formerly leaning against the table." "Indeed," said Sir Motley, "your question is a good one, Yen. Just now, I lost myself. Can you understand this? You may have heard the pipes of man, but not the pipes of earth. You may have heard the pipes of earth, but not the pipes of heaven." (2)[31]

Victor Mair presentsZhuangzievidence for "close affinities between the Daoist sages and the ancient Indian holy men.[32]Yogic breath control andasanas(postures) were common to both traditions. "First, this reference to" breathing from the heels ", which is a modern explanation of thesirsasana"supported headstand".

The true man [i.e.,zhenren] of old did not dream when he slept and did not worry when he was awake. His food was not savory, his breathing was deep. The breathing of the true man is from his heels, the breathing of the common man is from his throat. The words of those who unwillingly yield catch in their throats as though they were retching. Those whose desires are deep-seated will have shallow natural reserves. (6)[33]

Second, this "bear strides and bird stretches" reference toxianpractices of yogic postures and breath exercises.

Retiring to bogs and marshes, dwelling in the vacant wilderness, fishing and living leisurely—all this is merely indicative of nonaction. But it is favored by the scholars of rivers and lakes, men who flee from the world and wish to be idle. Blowing and breathing, exhaling and inhaling, expelling the old and taking in the new, bear strides and bird stretches—all this is merely indicative of the desire for longevity. But it is favored by scholars who channel the vital breath and flex the muscles and joints, men who nourish the physical form so as to emulate the hoary age of Progenitor P'eng [i.e.,Peng Zu]. (15)[34]

Mair previously[35]noted the (c. 168 BCE)Mawangdui Silk Texts,famous for twoTao Te Chingmanuscripts, include a painted text that illustrates gymnastic exercises–including the "odd expression 'bear strides'".

Xingqijade inscription

[edit]Some writing on a Warring States era jade artifact could be an earlier record of breath meditation than theNeiye,Tao Te Ching,orZhuangzi.[36]This rhymed inscription entitledTính khíHành khí"circulatingqi"was inscribed on adodecagonalblock of jade, tentatively identified as a pendant or a knob for a staff. While the dating is uncertain, estimates range from approximately 380 BCE (Guo Moruo) to earlier than 400 BCE (Joseph Needham). In any case, Roth says, "both agree that this is the earliest extant evidence for the practice of guided breathing in China".[37]

The inscription says:

To circulate the Vital Breath:

Breathe deeply, then it will collect.

When it is collected, it will expand.

When it expands, it will descend.

When it descends, it will become stable.

When it is stable, it will be regular.

When it is regular, it will sprout.

When it sprouts, it will grow.

When it grows, it will recede.

When it recedes, it will become heavenly.

The dynamism of Heaven is revealed in the ascending;

The dynamism of Earth is revealed in the descending.

Follow this and you will live; oppose it and you will die.[38]

Practicing this series of exhalation and inhalation patterns, one becomes directly aware of the "dynamisms of Heaven and Earth" through ascending and descending breath.TianjiThiên cơ,translated "dynamism of Heaven", also occurs in theZhuangzi(6),[33]as "natural reserves" in "Those whose desires are deep-seated will have shallow natural reserves".Roth notes the final line's contrasting verbs,xunHuấn"follow; accord with" andniNghịch"oppose; resist", were similarly used in the (168 BCE)Huangdi SijingYin-yangsilk manuscripts.[39]

Han dynasty

[edit]As Daoism was flourishing during theHan dynasty(206 BCE–220 CE), meditation practitioners continued early techniques and developed new ones.

Huainanzi

[edit]The (139 BCE)Huainanzi,which is an eclectic compilation attributed toLiu An,frequently describes meditation, especially as a means for rulers to achieve effective government.

Internal evidence reveals that theHuainanziauthors were familiar with theGuanzimethods of meditation.[40]The text usesxinshuRắp tâm"mind techniques" both as a general term for "inner cultivation" meditation practices and as a specific name for theGuanzichapters.[41]

The essentials of the world: do not lie in the Other but instead lie in the self; do not lie in other people but instead lie in your own person. When you fully realize it [the Way] in your own person, then all the myriad things will be arrayed before you. When you thoroughly penetrate the teachings of the Techniques of the Mind, then you will be able to put lusts and desires, likes and dislikes, outside yourself.[42]

SeveralHuainanzipassages associate breath control meditation with longevity and immortality.[43]For example, two famousxian"immortals":

Now Wang Qiao and Chi Songzi exhaled and inhaled, spitting out the old and internalizing the new. They cast off form and abandoned wisdom; they embraced simplicity and returned to genuineness; in roaming with the mysterious and subtle above, they penetrated to the clouds and Heaven. Now if one wants to study their Way and does not attain their nurturing of theqiand their lodging of the spirit but only imitates their every exhale and inhale, their contracting and expanding, it is clear that one will not be able to mount the clouds and ascend on the vapors.[44]

Heshang gongcommentary

[edit]The (c. 2nd century CE)Tao Te Chingcommentary attributed toHeshang GongTrên sông công(lit. "Riverbank Elder" ) provides what Kohn calls the "first evidence for Daoist meditation" and "proposes a concentrative focus on the breath for harmonization with the Dao".[1]

Eduard Erkes says the purpose of the Heshang Gong commentary was not only to explicate theTao Te Ching,but chiefly to enable "the reader to make practical use of the book and in teaching him to use it as a guide to meditation and to a life becoming a Daoist skilled in meditative training".[45]

Two examples fromTao Te Ching10 (see above) are the Daoist meditation termsxuanlanHuyền lãm(lit. "dark/mysterious display" ) "observe with a tranquil mind" andtianmenThiên môn(lit. "gate of heaven" ) "middle of the forehead".Xuanlanoccurs in the lineGột sạch huyền lãmthat Mair renders "Cleanse the mirror of mysteries". Erkes translates "By purifying and cleansing one gets the dark look",[46]because the commentary says, "One must purify one's mind and let it become clear. If the mind stays in dark places, the look knows all its doings. Therefore it is called the dark look." Erkes explainsxuanlanas "the Daoist term for the position of the eyes during meditation, when they are half-closed and fixed on the point of the nose."Tianmenoccurs in the lineThiên môn khép mở"Open and close the gate of heaven". The Heshang commentary[47]says, "The gate of heaven is called the purple secret palace of the north-pole. To open and shut means to end and to begin with the five junctures. In the practice of asceticism, the gate of heaven means the nostrils. To open means to breathe hard; to shut means to inhale and exhale."

Taiping jing

[edit]The (c. 1st century BCE to 2nd century CE)Taiping Jing"Scripture of Great Peace" emphasizedshouyi"guarding the One" meditation, in which one visualizes different cosmic colors corresponding with different parts of one's body.

In a state of complete concentration, when the light first arises, make sure to hold on to it and never let it go. First of all, it will be red, after a long time it will change to be white, later again it will be green, and then it will pervade all of you completely. When you further persist in guarding the One, there will be nothing within that would not be brilliantly illuminated, and the hundred diseases will be driven out.[48]

Besides "guarding the One" where a meditator is assisted by the god of Heaven, theTaiping jingalso mentions "guarding the Two" with help from the god of Earth, "guarding the Three" with help from spirits of the dead, and "guarding the Four" or "Five" in which one is helped by the myriad beings.[49]

TheTaiping jing shengjun bizhiThái bình kinh thánh quân bí chỉ"Secret Directions of the Holy Lord on the Scripture of Great Peace" is a Tang-period collection ofTaiping jingfragments concerning meditation. It provides some detailed information, for instance, interpretations of the colors visualized.

In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light as bright the rising sun. This is a brilliance as strong as that of the sun at noon. In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light entirely green. When this green is pure, it is the light of lesser yang. In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light entirely red, just like fire. This is a sign of transcendence. In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light entirely yellow. When this develops a greenish tinge, it is the light of central harmony. This is a potent remedy of the Tao. In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light entirely white. When this is as clear as flowing water, it is the light of lesser yin. In guarding the light of the One, you may see a light entirely black. When this shimmers like deep water, it is the light of greater yin.[50]

In the year 142,Zhang Daolingfounded theTianshi"Celestial Masters" movement, which was the first organized form of Taoist religion. Zhang and his followers practicedTaiping jingmeditation and visualization techniques. After theWay of the Five Pecks of Ricerebellion against the Han dynasty, Zhang established a theocratic state in 215, which led to the downfall of the Han.

Six Dynasties

[edit]The historical term "Six Dynasties"collectively refers to theThree Kingdoms(220–280 CE),Jin dynasty (266–420),andSouthern and Northern Dynasties(420–589). During this period of disunity after the fall of the Han, Chinese Buddhism became popular and new schools of religious Daoism emerged.

Early visualization meditation

[edit]Daoism's "first formal visualization texts appear" in the 3rd century.[1]

TheHuangting jingHoàng đình kinh"Scripture of the Yellow Court" is probably the earliest text describing inner gods and spirits located in the human body. Meditative practices described in theHuangting jinginclude visualization of bodily organs and their gods, visualization of the sun and moon, and absorption ofneijingNội cảnh"inner light".

TheLaozi zhongjingLão tử trung kinh"Central Scripture of Laozi" similarly describes visualizing and activating gods within the body, along with breathing exercises for meditation and longevity techniques. The adept envisions the yellow and red essences of the sun and moon, which activatesLaoziandYunüNgọc nữ"Jade Woman" within the abdomen, producing theshengtaiThánh thai"sacred embryo".

TheCantong qi"Kinship of the Three", attributed toWei Boyang(fl. 2nd century), criticizes Daoist methods of meditation on inner deities.

Baopuzi

[edit]The Jin dynasty scholarGe Hong's (c. 320)Baopuzi"Master who Embraces Simplicity", which is an invaluable source for early Daoism, describesshouyi"guarding the One" meditation as a source for magical powers from thezhenyiThật một"True One".

Realizing the True One, the original unity and primordial oneness of all, meant placing oneself at the center of the universe, identifying one's physical organs with constellations in the stars. The practice led to control over all the forces of nature and beyond, especially over demons and evil forces.[51]

Ge Hong says his teacher Zheng YinTrịnh ẩntaught that:

If a man can preserve Unity, Unity will also preserve him. In this way the bare blade finds no place in his body to inserts its edge; harmful things find no place in him that will admit entrance to their evil. Therefore, in defeat it is possible to be victorious; in positions of peril, to feel only security. Whether in the shrine of a ghost, in the mountains or forests, in a place suffering the plague, within a tomb, in bush inhabited by tigers and wolves, or in the habitation of snakes, all evils will go far away as long as one remains diligent in the preservation of Unity. (18)[52]

TheBaopuzialso comparesshouyimeditation with a complexmingjingGương sáng"bright mirror"multilocationvisualization process through which an individual can mystically appear in several places at once.

My teacher used to say that to preserve Unity was to practice jointly Bright Mirror, and that on becoming successful in the mirror procedure a man would be able to multiply his body to several dozen all with the same dress and facial expression. (18)[53]

Shangqing meditation

[edit]The Daoist school ofShangqing"Highest Clarity" traces its origins toWei Huacun(252–334), who was a Tianshi adept proficient in meditation techniques. Shangqing adopted theHuangting jingas scripture, and thehagiographyof Wei Huacun claims axian"immortal" transmitted it (and thirty other texts) to her in 288. Additional divine texts were supposedly transmitted toYang Xifrom 364 to 370, constituting the Shangqing scriptures.

The practices they describe include not only concentration on thebajingTám cảnh(Eight Effulgences) and visualization of gods in the body, but also active interaction with the gods, ecstatic excursions to the stars and the heavens of the immortals (yuanyouĐi xa), and the activation of inner energies in a protoform of inner alchemy (neidan). The world of meditation in this tradition is incomparably rich and colorful, with gods, immortals, body energies, and cosmic sprouts vying for the adept's attention.[54]

Lingbao meditation

[edit]Beginning around 400 CE, theLingbao"NuminousTreasure "School eclectically adopted concepts and practices from Daoism and Buddhism, which had recently been introduced to China.Ge Chaofu,Ge Hong's grandnephew, "released to the world" theWufu jingNăm phù kinh"Talismans of the Numinous Treasure" and other Lingbao scriptures, and claimed family transmission down fromGe Xuan(164–244), Ge Hong's great uncle.[55]

The Lingbao School added the Buddhist concept ofreincarnationto the Daoist tradition ofxian"immortality; longevity", and viewed meditation as a means to unify body and spirit.[56]

Many Lingbao meditation methods came from native Chinese traditions, such as visualizing inner gods (Taiping jing), and circulating the solar and lunar essences (Huangting jingandLaozi zhongjing). Meditation rituals changed from individuals practicing privately to Lingbao clergy worshipping communally; frequently with the "multidimensional quality" of a priest performing interior visualizations while leading congregants in communal visualization rites.[57]

Buddhist influences

[edit]During the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, the introduction of traditionalBuddhist meditationmethods richly influenced Daoist meditation.

The (c. late 5th-century)The Northern Celestial MasterstextXishengjing"Scripture of Western Ascension" recommends cultivating an empty state of consciousness calledwuxinVô tâm(lit. "no mind" ) "cease all mental activity" (translatingSanskritacittafromcittaचित्त"mind" ), and advocates a simple form ofguanXem"observation" insight meditation (translatingvipassanāfromvidyāविद्या"knowledge" ).[54]

Two earlyChinese encyclopedias,the (c. 570) Daoist encyclopediaWushang biyaoVô thượng bí muốn"Supreme Secret Essentials" and the (7th century) BuddhisticDaojiao yishuĐạo giáo nghĩa xu"Pivotal Meaning of Daoist Teachings" distinguish various levels ofguanXem"observation" insight meditation, under the influence of the BuddhistMadhyamakaschool'sTwo truths doctrine.TheDaojiao yishu,for instance, says.

Realize also that in concentration and insight, one does not reach enlightenment and perfection of body and mind through the two major kinds of observation [of energy and spirit] alone. Rather, there are five different sets of three levels of observation. One such set of three is: 1. Observation of apparent existence. 2. Observation of real existence. 3. Observation of partial emptiness.[58]

Tang dynasty

[edit]Daoism was in competition with Confucianism and Buddhism during theTang dynasty(618–907), and Daoists integrated new meditation theories and techniques from Buddhists.

The 8th century was a "heyday" of Daoist meditation;[54]recorded in works such asSun Simiao'sCunshen lianqi mingTồn thần Luyện Khí minh"Inscription on Visualization of Spirit and Refinement of Energy", Sima ChengzhenTư Mã thừa trinh'sZuowanglun"Essay on Sitting in Forgetfulness", and Wu YunNgô quân'sShenxian kexue lunThần tiên nhưng học luận"Essay on How One May Become a Divine Immortal through Training". These Daoist classics reflect a variety of meditation practices, including concentration exercises, visualizations of body energies and celestial deities to a state of total absorption in the Dao, and contemplations of the world.

The (9th century)Qingjing Jing"Scripture of Clarity and Quiescence" associates the Tianshi tradition of a divinized Laozi with Daoistguanand Buddhistvipaśyanāmethods of insight meditation.

Song dynasty

[edit]Under theSong dynasty(960–1279), the Daoist schools ofQuanzhen"Complete Authenticity" andZhengyi"Orthodox Unity" emerged, andNeo-Confucianismbecame prominent.

Along with the continued integration of meditation methods, two new visualization and concentration practices became popular.[54]Neidan"inner alchemy" involved the circulation and refinement of inner energies in a rhythm based on theYijing.Meditation focused upon starry deities (e.g., theSantaiTam đài"Three Steps" stars inUrsa Major) and warrior protectors (e.g., theXuanwuHuyền Vũ"Dark Warrior;Black Tortoise"Northern Sky spirit).

Later dynasties

[edit]

During theYuan dynasty(1279–1367), Daoists continued to develop the Song period practices ofneidanalchemy and deity visualizations.

Under theMing dynasty(1368–1644),neidanmethods were interchanged between Daoism andChan Buddhism.Many literati in thescholar-officialclass practiced Daoist and Buddhist meditations, which exerted a stronger influence on Confucianism.[59]

In theQing dynasty(1644–1912), Daoists wrote the first specialized texts onnüdanNữ đan"inner alchemy for women", and developed new forms of physical meditation, notablyTaijiquan—sometimes described as meditation in motion or moving meditation. ThisNeijiainternal martial art is named after theTaijitusymbol, which was a traditional focus in both Daoist andNeo-Confucianmeditation.

Modern period

[edit]Daoism and other Chinese religions were suppressed under theRepublic of China(1912–1949) and in thePeople's Republic of Chinafrom 1949 to 1979. Many Daoist temples and monasteries have been reopened in recent years.

Western knowledge of Daoist meditation was stimulated byRichard Wilhelm's (German 1929, English 1962)The Secret of the Golden Flowertranslation of the (17th century)neidantextTaiyi jinhua zongzhiThái Ất kim hoa tôn chỉ.

In the 20th century, theQigongmovement has incorporated and popularized Daoist meditation, and "mainly employs concentrative exercises but also favors the circulation of energy in an inner-alchemical mode".[59]Teachers have created new methods of meditation, such asWang Xiangzhai'szhan zhuang"standing like a post" in theYiquanschool.

References

[edit]- Erkes, Eduard (1945). "Ho-Shang-Kung's Commentary on Lao-tse - Part I".Artibus Asiae.8(2/4): 121–196.doi:10.2307/3248186.JSTOR3248186.

- Harper, Donald (1999). "Warring States Natural Philosophy and Occult Thought". In M. Loewe; E. L. Shaughnessy (eds.).The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C.Cambridge University Press. pp. 813–884.

- Kohn, Livia, ed. (1989a).Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques.Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.ISBN9780892640850.

- Kohn, Livia (1989b). "Guarding the One: Concentrative Meditation in Taoism". In Livia Kohn (ed.).Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques.Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. pp. 125–158.ISBN978-0892640850.

- Kohn, Livia (1989c). "Taoist Insight Meditation: The Tang Practice of 'Neiguan'".In Livia Kohn (ed.).Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques.Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. pp. 193–224.ISBN978-0892640850.

- Kohn, Livia (1993).The Taoist Experience: An Anthology.SUNY Press.

- Kohn, Livia (2008a). "Meditation and visualization". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge.ISBN9780700712007.

- Kohn, Livia (2008c). "DingĐịnhconcentration ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge.ISBN9780700712007.

- Kohn, Livia (2008d). "GuanXemobservation ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge.ISBN9780700712007.

- Luk, Charles (1964),The Secrets of Chinese Meditation: self-cultivation by mind control as taught in the Ch'an Mahayana and Taoist schools in China,Rider and Co.

- Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu.Translated by Mair, Victor H. Bantam Books. 1994.

- Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah; Meyer, Andrew; Roth, Harold (2010).The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, by Liu An, King of Huainan.Columbia University Press.

- Maspero, Henri (1981),Taoism and Chinese Religion,tr. by Frank A. Kierman Jr., University of Massachusetts Press.

- Peerenboom, Randal P. (1995).Law and Morality in Ancient China: the Silk Manuscripts of Huang-Lao.SUNY Press.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1989c), "Visualization and Ecstatic Flight in Shangqing Taoism," in Kohn (1989a), 159–191

- Robinet, Isabelle (1993),Taoist Meditation: The Mao-shan Tradition of Great Purity,SUNY Press.

- Roth, Harold D. (December 1991). "Psychology and Self-Cultivation in Early Taoistic Thought".Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies.51(2): 599–650.doi:10.2307/2719289.JSTOR2719289.

- Roth, Harold D. (1997). "Evidence for Stages of Meditation in Early Taoism".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.60(2): 295–314.doi:10.1017/S0041977X00036405.JSTOR620386.S2CID162615630.

- Roth, Harold D. (1999).Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism.Columbia University Press.

- Sha, Zhi Gang (2010).Tao II: The Way of Healing, Rejuvenation, Longevity, and Immortality.New York City: Simon & Schuster.

- Ware, James R., ed. (1966).Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: TheNei Pienof Ko Hung.Translated by James R. Ware. Dover Pubns.

Footnotes

- ^abcKohn 2008a,p. 118.

- ^Kohn 2008c,p. 358.

- ^Kohn 2008d,p. 452.

- ^Kohn 2008d,p. 453.

- ^Kohn, Livia (2008). "CunTồnvisualization, actualization ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. p. 287.ISBN9780700712007.

- ^Kohn 1989b.

- ^Zhi Gang Sha (2010), pp. 135, 257.[full citation needed]

- ^E.g.,Harper 1999,p. 880;Roth 1999,p. 25.

- ^Graham, Angus C. (1989),Disputers of the Tao,Open Court Press. P. 100.

- ^Roth 1991,pp. 611–2.

- ^Roth 1991.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 114.

- ^Tr.Roth 1999,p. 60.

- ^Roth 1991,pp. 619.

- ^Tr.Roth 1999,p. 78.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 116.

- ^Tr.Roth 1999,p. 92.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 78.

- ^Peerenboom 1995,p. 179.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 150.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 69.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 92.

- ^Tr.Roth 1999,p. 82.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 70.

- ^Tr.Erkes 1945,p. 122.

- ^Roth 1991,p. 602.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 32.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 64.

- ^Roth 1999,p. 154.

- ^Peerenboom 1995,p. 198.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 10.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 371.

- ^abMair 1994,p. 52.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 145.

- ^Mair 1991,p. 159[full citation needed].

- ^Harper 1999,p. 881.

- ^Roth 1997,p. 298.

- ^Tr.Roth 1997,p. 298.

- ^Roth 1997,pp. 298–9.

- ^Roth 1991,pp. 630.

- ^Major et al. 2010,p. 44.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 71.

- ^Roth 1991,pp. 648.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 414.

- ^Erkes 1945,pp. 127–8.

- ^Erkes 1945,p. 142.

- ^Tr.Erkes 1945,p. 143.

- ^Tr.Kohn 1989b,p. 140.

- ^Kohn 1989b,p. 139.

- ^Tr.Kohn 1993,pp. 195–6.

- ^Kohn 1993,p. 197.

- ^Tr.Ware 1966,pp. 304–5.

- ^Tr.Ware 1966,p. 306.

- ^abcdKohn 2008a,p. 119.

- ^Bokenkamp, Stephen (2008). "Lingbao". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. p. 664.ISBN9780700712007.

- ^Robinet (1997), p. 157.[full citation needed]

- ^Robinet (1997), p. 167.[full citation needed]

- ^Tr.Kohn 1993,p. 225.

- ^abKohn 2008a,p. 120.

External links

[edit]- Daoist meditation,The Daoist Foundation

- On Sitting in Oblivion,FYSK Daoist Culture Centre

- Tàishàng Lǎojūn Nèiguānjīng Classic of Inner Contemplation,Tàishàng Lǎojūn Nèiguānjīng Classic of Inner Contemplation