Tartessian language

| Tartessian | |

|---|---|

| Region | SouthwestIberian Peninsula |

| Extinct | after 5th century BC[1] |

| Southwest Paleo-Hispanic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | txr |

txr | |

| Glottolog | tart1237 |

Approximate extension of the area under Tartessian influence | |

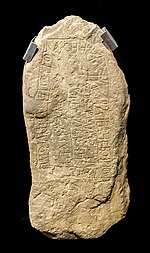

Tartessianis an extinctPaleo-Hispanic languagefound in theSouthwestern inscriptionsof theIberian Peninsula,mainly located in the south ofPortugal(Algarveand southernAlentejo), and the southwest ofSpain(south ofExtremaduraand westernAndalusia). There are 95 such inscriptions, the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one third of them were found in EarlyIron Agenecropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them to the 7th century BC and to consider the southwestern script to be the most ancientPaleo-Hispanic script,with characters most closely resembling specificPhoenician letter formsfound in inscriptions dated toc.825 BC. Five of the inscriptions occur onstelaethat have been interpreted as LateBronze Agecarved warrior gear from theUrnfield culture.[2]

Name[edit]

Most researchers use the termTartessianto refer to the language as attested on thestelaewritten in the Southwestern script,[3]but some researchers would prefer to reserve the termTartessianfor the language of the core Tartessian zone, which is attested for those researchers with somearchaeological graffiti[4]– like the Huelva graffito[5]and maybe with somestelae[6]such asVillamanrique de la Condesa(J.52.1).[7]Such researchers consider that the language of the inscriptions found outside the core Tartessian zone would be either a different language[8]or maybe a Tartessian dialect[9]and so they would prefer to identify the language of thestelaewith a different title: "southwestern"[10]or "south-Lusitanian".[11]There is general agreement that the core area ofTartessosis aroundHuelva,extending to the valley of theGuadalquivir,but the area under Tartessian influence is much wider[12](see maps). Three of the 95stelaeand some graffiti, belong to the core area:Alcalá del Río(Untermann J.53.1),Villamanrique de la Condesa(J.52.1) andPuente Genil(J.51.1). Four have also been found in the Middle Guadiana (in Extremadura), and the rest have been found in the south of Portugal (Algarve and Lower Alentejo), where the Greek and Roman sources locate the pre-RomanCempsi and SefesandCynetespeoples.

History[edit]

The most confident dating is for the Tartessian inscription (J.57.1) in the necropolis atMedellín,Badajoz,Spain to 650/625 BC.[13]Further confirmatory dates for the Medellín necropolis include painted ceramics of the 7th–6th centuries BC.[14]

In addition, a graffito on a Phoenician shard dated to the early to mid 7th century BC and found at the Phoenician settlement of Doña Blanca near Cadiz has been identified as Tartessian by the shape of the signs. It is only two signs long, reading]tetu[or perhaps]tute[.It does not show the syllable-vowel redundancy more characteristic of the southwestern script, but it is possible that this developed as indigenous scribes adapted the script from archaic Phoenician and other such exceptions occur (Correa and Zamora 2008).

The script used in the mint of Salacia (Alcácer do Sal,Portugal) from around 200 BC may be related to the Tartessian script, though it has no syllable-vowel redundancy; violations of this are known, but it is not clear if the language of this mint corresponds with the language of thestelae(de Hoz 2010).

TheTurdetaniof the Roman period are generally considered the heirs of the Tartessian culture.Strabomentions that: "The Turdetanians are ranked as the wisest of the Iberians; and they make use of an Alpha bet, and possess records of their ancient history, poems, and laws written in verse that are six thousand years old, as they assert."[15]It is not known when Tartessian ceased to be spoken, but Strabo (writing c. 7 BC) records that "The Turdetanians... and particularly those that live about the Baetis, have completely changed over to the Roman mode of life; with most of the populace not even remembering their own language any more."[16]

Writing[edit]

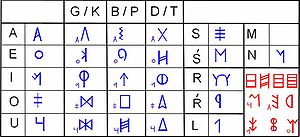

Tartessian inscriptions are in theSouthwestern script,which is also known as the Tartessian or South Lusitanian script. Like all otherPaleo-Hispanic scripts,except for theGreco-Iberian Alpha bet,Tartessian uses syllabic glyphs forplosive consonantsand Alpha betic letters for other consonants. Thus, it is a mixture of anAlpha betand asyllabarythat is called asemi-syllabary.Some researchers believe these scripts are descended solely from thePhoenician Alpha bet,but others think that theGreek Alpha bethad an influence as well.

The Tartessian script is very similar to theSoutheastern Iberian script,both in the shapes of the signs and in their values. The main difference is that the Southeastern Iberian script does not redundantly mark the vocalic values of syllabic characters, which was discovered by Ulrich Schmoll and allows the classification of most of the characters intovowels,consonantsand syllabic characters. As of the 1990s, the decipherment of the script was largely complete and so the sound values of most of the characters are known.[17][18]Like most other Paleo-Hispanic scripts, Tartessian does not distinguish betweenvoiced and unvoiced consonants([t]from[d],[p]from[b]or[k]from[ɡ]).[19]

Tartessian is written inscriptio continua,which complicates the identification of individual words.

Classification[edit]

Tartessian is generally left unclassified for lack of data or proposed to be alanguage isolatefor lack of connections to theIndo-European languages.[20][21]Some Tartessian names have been interpreted as Indo-European, more specifically asCeltic.[22]However, the language as a whole remains inexplicable from the Celtic or Indo-European point of view; the structure of Tartessian syllables appears to be incompatible with Celtic or even Indo-Europeanphoneticsand more compatible withIberianorBasque;some scholars consider that all Celtic elements are borrowings.[23]

Since 2009,John T. Kochhas argued that Tartessian is aCeltic languageand that the texts can be translated.[24][25][26][27]Koch's thesis has been popularised by the BBC TV seriesThe Celts: Blood, Iron and Sacrifice[28]and the associated book byAlice Roberts.[29][better source needed]

Although others such asTerrence Kaufman[30]have suggested that Tartessian may be a Celtic language, this proposal is widely rejected by linguists.[31]The current academic consensus regarding the classification of Tartessian as a Celtic language is summarized by de Hoz:[32]

J. Koch’s recent proposal that the south-western inscriptions should be deciphered as Celtic has had considerable impact, above all in archaeological circles. However, the almost unanimous opinion of scholars in the field of Palaeohispanic studies is that, despite the author’s indisputable academic standing, this is a case of a false decipherment based on texts that have not been sufficiently refined, his acceptance of a wide range of unjustified variations, and on purely chance similarities that cannot be reduced to a system; these deficiencies give rise to translations lacking in parallels in the recorded epigraphic usage.

Texts[edit]

(The following are examples of Tartessian inscriptions. Untermann's numbering system, or location name in newer transcriptions, is cited in brackets, e.g. (J.19.1) or (Mesas do Castelinho). Transliterations are by Rodríguez Ramos [2000].)

Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar):

- tᶤilekᵘuṟkᵘuarkᵃastᵃaḇᵘutᵉebᵃantᶤilebᵒoiirerobᵃarenaŕḵᵉ[en?]aφiuu

- lii*eianiitᵃa

- eanirakᵃaltᵉetᵃao

- bᵉesaru[?]an

Segmentation:Tᶤilekᵘuṟkᵘuarkᵃastᵃaḇᵘutᵉebᵃan.Tᶤile bᵒoii tᵉero bᵃarenaŕkᵉeaφiuuliieianii.TᵃaeaniraKᵃaltᵉe.Tᵃaobᵉesaru[?]an.

This is the longest Tartessian text known at present, with 82 signs, 80 of which have an identifiable phonetic value. The text is complete if it is assumed that the damaged portion contains a common, if poorly-understood, Tartessian phrase-formbᵃare naŕkᵉe[n—].[33]The formula contains two groups of Tartessian stems that appear to inflect as verbs:naŕkᵉe,naŕkᵉen,naŕkᵉeii,naŕkᵉenii,naŕkᵉentᶤi,naŕkᵉenaiandbᵃare,bᵃaren,bᵃareii,bᵃarentᶤifrom comparison with other inscriptions.[33]

Fonte Velha (Bensafrim) (J.53.1):

- lokᵒobᵒoniirabᵒotᵒoaŕaiaikᵃaltᵉelokᵒonanenaŕ[–]ekᵃa[?]ᶤiśiinkᵒolobᵒoiitᵉerobᵃarebᵉetᵉasiioonii[34]

Segmentation:Logoboniira botoaŕaiaigalte,logonanenaŕeŋaginśiiugoloboii tero barebetasiioonii.

Herdade da Abobada (Almodôvar) (J.12.1):

- iŕualkᵘusielnaŕkᵉentᶤimubᵃatᵉerobᵃare[?]ᵃatᵃaneatᵉe[34]

Segmentation:iŕual kᵘusielnaŕkᵉentᶤimubᵃatᵉero bᵃare-[?]ᵃa.Tᵃane atᵉe.

In the texts above, there are repetition ofbᵃare-,naŕkᵉe-, tᶤile-, bᵒoii-, -tᵉero-, kᵃaltᵉe-, lok-, -ᵒonii,whereasbᵒoii tᵉero-bᵃarerepeats three times, with assumablyreroas a corruption oftᵉeroin Mesas do Castelinho transcription.tᶤile-andlokᵒoappear in the beginning of their sentences.

See also[edit]

- Arganthonios

- Celtiberian language

- Hispano-Celtic languages

- Iberian language

- Lusitanian language

- National Museum of Archaeology (Portugal)

- Paleohispanic languages

- Phoenician language

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

References[edit]

- ^"Tartessian".Archived fromthe originalon December 20, 2012.Retrieved2024-01-31.

- ^Koch, John T. (2013).Celtic from the West 2 - Prologue: The Earliest Hallstatt Iron Age cannot equal Proto-Celtic.Oxford:Oxbow Books.pp. 10–11.ISBN978-1-84217-529-3.Archived fromthe originalon 2013-01-21.Retrieved2014-03-14.

- ^Untermann (1997);Koch 2009-2012, Villar Liebana 2004–2012, Yocum 2012, &c.

- ^Correa (2009),p. 277; de Hoz 2007, p. 33; 2010, pp. 362–364.

- ^Untermann (1997),pp. 102–103; Mederos and Ruiz 2001.

- ^Correa 2009,p. 276.

- ^Catalogue numbers for inscriptions refer toUntermann (1997)

- ^Villar Liebana (2000),p. 423; Rodríguez Ramos 2009, p. 8; de Hoz 2010, p. 473.

- ^Correa 2009,p. 278.

- ^Villar Liebana (2000);de Hoz 2010.

- ^Rodríguez Ramos 2009

- ^Koch 2010 2011

- ^Almagro-Gorbea, M (2004). "Inscripciones y grafitos tartésicos de la necrópolis orientalizante de Medellín".Palaeohispanica:4.13–44.

- ^Ruiz, M M (1989). "Las necrópolis tartésicas: prestigio, poder y jerarquas".Tartessos: Arqueología Protohistórica del Bajo Guadalquivir:269.

- ^Strabo,Geography,book 3, chapter 1, section 6.

- ^Strabo,Geography,book 3, chapter 2, section 15.

- ^Untermann, Jürgen(1995). "Zum Stand der Deutung der" tartessischen "Inschriften".Hispano- Gallo-Brittonica: essays in honour of Professor D. Ellis Evans on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday.Cardiff:University of Wales Press.pp. 244–59.

- ^Untermann, Jürgen, ed. (1997).Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum; herausgegeben von Jürgen Untermann; unter Mitwirkungen von Dagmar Wodtko. Band IV, Die tartessischen, keltiberischen und lusitanischen Inschriften[Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum; edited by Jürgen Untermann; with the participation of Dagmar Wodtko. Volume IV, The Tartessian, Celtiberian and Lusitanian Inscriptions] (in German). Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert.

- ^"O'Donnell Lecture 2008 Appendix"(PDF).

- ^Rodríguez Ramos (2002)

- ^de Hoz (2010)

- ^Correa (1989);Untermann (1997)

- ^(Rodríguez Ramos 2002, de Hoz 2010)

- ^Koch, John T. (2009).Tartessian. Celtic in the South-West at the Dawn of History.Celtic Studies Publications, Aberystwyth.ISBN978-1-891271-17-5.

- ^Koch, John T (2011).Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology.Celtic Studies Publications, Aberystwyth. pp. 1–198.ISBN978-1-907029-07-3.

- ^Villar Liebana, Francisco(2011).Lenguas, genes y culturas en la prehistoria de Europa y Asia suroccidental[Languages, genes and cultures in the prehistory of Europe and Southwest Asia] (in Spanish). Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca. p. 100.ISBN978-84-7800-135-4.

- ^Koch, John T."Common Ground and Progress on the Celtic of the South-western SW Inscriptions".Academia.edu.Retrieved3 March2017.

- ^"The Celts: Blood, Iron and Sacrifice".BBC.Retrieved9 October2015.

- ^Roberts, Alice (2015).The Celts: Search for a Civilisation.Heron Books.ISBN978-1784293321.

- ^Terrence Kaufman. 2015. Notes on the Decipherment of Tartessian as Celtic. Institute for the Study of Man Incorporated

- ^Sims-Williams, Patrick (2 April 2020)."An Alternative to 'Celtic from the East' and 'Celtic from the West'".Cambridge Archaeological Journal.30(3): 511–529.doi:10.1017/s0959774320000098.hdl:2160/317fdc72-f7ad-4a66-8335-db8f5d911437.ISSN0959-7743.S2CID216484936.

- ^Hoz, J. de (28 February 2019),"Method and methods",Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies,Oxford University Press,pp. 1–24,doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790822.003.0001,ISBN978-0-19-879082-2,retrieved29 May2021

- ^abGuerra 2009.

- ^abUntermann 1997.

Further reading[edit]

- Ballester, Xaverio(2004): «Hablas indoeuropeas y anindoeuropeas en la Hispania prerromana»,Estudios de lenguas y epigrafía Antiguas – ELEA6, pp. 107–138.

- Broderick, George (2010):«Das Handbuch der Eurolinguistik»,Die vorrömischen Sprachen auf der iberischen Halbinsel,ISBN3-447-05928-1,pp. 304–305

- Correa, José Antonio (1989). ""Posibles antropónimos en las inscripciones en escritura del S.O. (o Tartesia)""[«Possible anthroponyms in the inscriptions in writing of the S.O. (or Tartessia)»].Veleia(in Spanish).6:243–252.

- Correa, José Antonio (1992): «La epigrafía tartesia»,Andalusien zwischen Vorgeshichte und Mittelalter,eds. D. Hertel & J. Untermann, pp. 75–114.

- Correa, José Antonio (1995): «Reflexiones sobre la epigrafía paleohispánica del suroeste de la Península Ibérica»,Tartessos 25 años después,pp. 609–618.

- Correa, José Antonio (2009). "«Identidad, cultura y territorio en la Andalucía prerromana a través de la lengua y la epigrafía»". In Alonso, F. Wulff; Martí-Aguilar, M. Álvarez (eds.).Identidades, culturas y territorios en la Andalucía prerromana.Málaga. pp. 273–295.

- Correa, José Antonio, Zamora, José Ángel (2008):«Un graffito tartessio hallado en el yacimiento del Castillo do Dona Blanca»,Palaeohispanica8, pp. 179–196.

- Correia, Virgílio-Hipólito (1996): «A escrita pré-romana do Sudoeste peninsular»,De Ulisses a Viriato: o primeiro milenio a.c.,pp. 88–94.

- Eska, Joseph (2013): Review:"John T. Koch, Barry W. Cunliffe (ed.), Celtic from the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo-European in Atlantic Europe. Celtic studies publications, 16. Oxford; Oakville, CT: Oxbow Books, 2013".Bryn Mawr Classical Review2013.12.35.

- Eska, Joseph (2014):«Comments on John T. Koch’s Tartessian-as-Celtic Enterprise»,Journal of Indo-European Studies42/3-4, pp. 428–438.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (2013):“Hispania Indoeuropea y no Indoeuropea”,inIberia e Sardegna: Legami linguistici, archeologici e genetici dal Mesolitico all’Età del Bronzo - Proceedings of the International Congress «Gorosti U5b3» (Cagliari-Alghero, June 12–16, 2012),pp. 47–64.

- Guerra, Amilcar (2002):«Novos monumentos epigrafados com escrita do Sudoeste da vertente setentrional da Serra do Caldeirão»,Revista Portuguesa de arqueologia5-2, pp. 219–231.

- Guerra, Amilcar (2009)."Novidades no âmbito da epigrafia pré-romana do sudoeste hispânico"[Novelties within the pre-Roman epigraphy of the Hispanic southwest](PDF).Acta Palaeohispanica X, Palaeohispanica(in Portuguese).9:323–338.

- Guerra, Amilcar (2013):“Algumas questões sobre as escritas pré-romanas do Sudoeste Hispánico”,inActa Palaeohispanica XI: Actas del XI coloquio internacional de lenguas y culturas prerromanas de la Península Ibérica (Valencia, 24-27 de octubre de 2012) (Palaeohispanica 13),pp. 323–345.

- Hoz, Javier de (1995): «Tartesio, fenicio y céltico, 25 años después»,Tartessos 25 años después,pp. 591–607.

- Hoz, Javier de (2007):«Cerámica y epigrafía paleohispánica de fecha prerromana»,Archivo Español de Arqueología80, pp. 29–42.

- Hoz, Javier de (2010):Historia lingüística de la Península Ibérica en la antigüedad: I. Preliminares y mundo meridional prerromano,Madrid, CSIC, coll. « Manuales y anejos de Emerita » (ISBN978-84-00-09260-3,ISBN978-84-00-09276-4).

- Koch, John T.(2010):«Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic»[permanent dead link],Oxbow Books, Oxford,ISBN978-1-84217-410-4pp. 187–295.

- Koch, John T.(2011):«Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology»,Oxbow Books, Oxford,ISBN978-1-907029-07-3pp. 1–198.

- Koch, John T.(2011):«The South-Western (SW) Inscriptions and the Tartessos of Archaeology of History»,Tarteso, El emporio del Metal,Huelva.

- Koch, John T.(2013):«Celtic from the West 2 Chapter 4: Out of the Flow and Ebb of the European Bronze Age: Heroes, Tartessos, and Celtic»Archived2013-01-21 at theWayback Machine,Oxbow Books, Oxford,ISBN978-1-84217-529-3pp. 101–146.

- Koch, John T. (2014a):«On the Debate over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, also known as Tartessian»,Journal of Indo-European Studies42/3-4, pp. 335–427.

- Koch, John T. (2014b):«A Decipherment Interrupted: Proceeding from Valério, Eska, and Prósper»,Journal of Indo-European Studies42/3-4, pp. 487–524.

- Mederos, Alfredo; Ruiz, Luis (2001):«Los inicios de la escritura en la Península ibérica. Grafitos en cerámicas del bronce final III y fenicias»[permanent dead link],Complutum12, pp. 97–112.

- Mikhailova, T. A. (2010) Review: "J.T. Koch. Tartessian: Celtic in the South-West at the Dawn of history (Celtic Studies Publication XIII). Aberystwyth: Centre for advanced Welsh and Celtic studies, 2009"Вопросы языкознания2010 №3; 140-155.

- Prósper, Blanca M. (2014):"Some Observations on the Classification of Tartessian as a Celtic Language".Journal of Indo-European Studies42/3-4, pp. 468–486.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2000):“La lectura de las inscripciones sudlusitano-tartesias”.Faventia22/1, pp 21–48.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002a):“El origen de la escritura sudlusitano-tartesia y la formación de alfabetos a partir de alefatos”.Rivista di Studi Fenici30/2, pp. 187–216.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002b):"Las inscripciones sudlusitano-tartesias: su función, lingua y contexto socioeconómico".Complutum13, pp. 85–95.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2009): «La lengua sudlusitana»,Studia Indogermanica LodziensiaVI, pp. 83–98.

- Valério, Miguel (2008 [2009]): “Origin and Development of the Paleohispanic scripts: The Orthography and Phonology of the Southwestern Alphabet".Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia11-2, pp. 107–138.[1]

- Valério, Miguel (2014):"The Interpretative Limits of the Southwestern Script".Journal of Indo-European Studies42/3-4, pp. 439–467.

- Untermann, Jürgen(2000). "Lenguas y escrituras en torno a Tartessos" [Languages and scripts around Tartessos].Argantonio: Rey de Tartessos[Argantonio: King of Tartessos] (in Spanish). Madrid. pp. 69–77.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Villar Liebana, Francisco(2000).Indoeuropeos y no indoeuropeos en la Hispania prerromana[Indo-Europeans and non-Indo-Europeans in pre-Roman Hispania] (in Spanish). Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.ISBN978-84-78-00968-8.

- Villar Liebana, Francisco (2004). "The Celtic Language of the Iberian Peninsula".Studies in Baltic and Indo-European Linguistics in Honor of William R. Schmalstieg.Current Issues in Linguistic Theory.254:243–274.doi:10.1075/cilt.254.30vil.ISBN978-90-272-4768-1.

- Wikander, Stig(1966): «Sur la langue des inscriptions Sud-Hispaniques», inStudia Linguistica20, 1966, pp. 1–8.

- Wodtko, Dagmar (2021). "De Ortografía Tartésica". In:Palaeohispanica.Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua 21 (diciembre), pp. 219–234.https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v21i0.411.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related toTartessian languageat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toTartessian languageat Wikimedia Commons