Coconut

| Coconut Temporal range:EarlyEocene– Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Subfamily: | Arecoideae |

| Tribe: | Cocoseae |

| Genus: | Cocos L. |

| Species: | C. nucifera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cocos nucifera L.

| |

| |

| Possible native range prior todomestication | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Thecoconut tree(Cocos nucifera) is a member of thepalm treefamily(Arecaceae) and the only livingspeciesof thegenusCocos.[1]The term "coconut"(or the archaic"cocoanut")[2]can refer to the wholecoconut palm,theseed,or thefruit,which botanically is adrupe,not anut.They are ubiquitous in coastal tropical regions and are a cultural icon of thetropics.

The coconut tree provides food, fuel, cosmetics, folk medicine and building materials, among many other uses. The inner flesh of the mature seed, as well as thecoconut milkextracted from it, forms a regular part of the diets of many people in the tropics andsubtropics.Coconuts are distinct from other fruits because theirendospermcontains a large quantity of an almost clear liquid, called "coconut water"or" coconut juice ". Mature, ripe coconuts can be used as edible seeds, or processed foroilandplant milkfrom the flesh,charcoalfrom the hard shell, andcoirfrom the fibroushusk.Dried coconut flesh is calledcopra,and the oil and milk derived from it are commonly used in cooking –fryingin particular – as well as insoapsandcosmetics.Sweet coconut sap can be made into drinks or fermented intopalm wineorcoconut vinegar.The hard shells, fibrous husks and long pinnate leaves can be used as material to make a variety of products forfurnishingand decoration.

The coconut has cultural and religious significance in certain societies, particularly in theAustronesiancultures of theWestern Pacificwhere it is featured in their mythologies, songs, and oral traditions. The fall of its mature fruit has led to a preoccupation withdeath by coconut.[3][4]It also had ceremonial importance in pre-colonialanimisticreligions.[3][5]It has also acquired religious significance inSouth Asiancultures, where it is used inritualsofHinduism.It forms the basis of wedding and worship rituals in Hinduism. It also plays a central role in theCoconut Religionfounded in 1963 inVietnam.

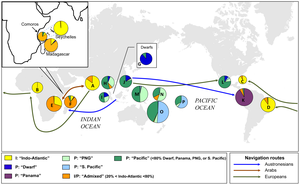

Coconuts were firstdomesticatedby theAustronesian peoplesinIsland Southeast Asiaand were spread during theNeolithicvia theirseaborne migrationsas far east as thePacific Islands,and as far west asMadagascarand theComoros.They played a critical role in the long sea voyages of Austronesians by providing a portable source of food and water, as well as providing building materials for Austronesianoutrigger boats.Coconuts were also later spread in historic times along the coasts of theIndianandAtlanticOceansbySouth Asian,Arab,andEuropeansailors. Based on these separate introductions, coconut populations can still be divided into Pacific coconuts and Indo-Atlantic coconuts, respectively. Coconuts were introduced by Europeans to theAmericasduring thecolonial erain theColumbian exchange,but there is evidence of a possiblepre-Columbianintroduction of Pacific coconuts toPanamaby Austronesian sailors. The evolutionary origin of the coconut is under dispute, with theories stating that it may have evolved inAsia,South America, or Pacific islands.

Trees can grow up to 30 metres (100 feet) tall and can yield up to 75 fruits per year, though fewer than 30 is more typical. Plants are intolerant to cold and prefer copious precipitation and full sunlight. Many insect pests and diseases affect the species and are a nuisance for commercial production. In 2022, about 73% of the world's supply of coconuts was produced byIndonesia,India,and thePhilippines.

Description

Cocos nuciferais a large palm, growing up to 30 metres (100 feet) tall, withpinnateleaves 4–6 m (13–20 ft) long, and pinnae 60–90 centimetres (2–3 ft) long; old leaves break away cleanly, leaving thetrunksmooth.[6]On fertile soil, a tall coconut palm tree can yield up to 75fruitsper year, but more often yields less than 30.[7][8][9]Given proper care and growing conditions, coconut palms produce their first fruit in six to ten years, taking 15 to 20 years to reach peak production.[10]

True-to-typedwarfvarieties of Pacific coconuts have been cultivated by theAustronesian peoplessince ancient times. These varieties were selected for slower growth, sweeter coconut water, and often brightly colored fruits.[11]Many modern varieties are also grown, including theMaypan,King,andMacapuno.These vary by the taste of the coconut water and color of the fruit, as well as other genetic factors.[12]

Fruit

Botanically,the coconut fruit is adrupe,not atrue nut.[13]Like other fruits, it hasthree layers:theexocarp,mesocarp,andendocarp.The exocarp is the glossy outer skin, usually yellow-green to yellow-brown in color. The mesocarp is composed of afiber,calledcoir,which has many traditional and commercial uses. Both the exocarp and the mesocarp make up the "husk" of the coconut, while the endocarp makes up the hard coconut "shell". The endocarp is around4 millimetres (1⁄8inch) thick and has three distinctivegerminationpores (micropyles) on the distal end. Two of the pores are plugged (the "eyes" ), while one is functional.[14][15]

The interior of the endocarp is hollow and is lined with a thin brownseed coataround0.2 mm (1⁄64in) thick. The endocarp is initially filled with a multinucleate liquidendosperm(thecoconut water). As development continues, cellular layers of endosperm deposit along the walls of the endocarp up to11 mm (3⁄8in) thick, starting at the distal end. They eventually form the edible solid endosperm (the "coconut meat" or "coconut flesh" ) which hardens over time. The small cylindricalembryois embedded in the solid endosperm directly below the functional pore of the endosperm. During germination, the embryo pushes out of the functional pore and forms ahaustorium(thecoconut sprout) inside the central cavity. The haustorium absorbs the solid endosperm to nourish the seedling.[14][16][17]

Coconut fruits have two distinctive forms depending on§ domestication.Wild coconuts feature an elongated triangular fruit with a thicker husk and a smaller amount of endosperm. These allow the fruits to be more buoyant and make it easier for them to lodge into sandy shorelines, making their shape ideal for ocean dispersal.[18][19][20] Domesticated Pacific coconuts, on the other hand, are rounded in shape with a thinner husk and a larger amount of endosperm. Domesticated coconuts also contain morecoconut water.[18][19][20] These two forms are referred to by theSamoantermsniu kafafor the elongated wild coconuts, andniu vaifor the rounded domesticated Pacific coconuts.[18][19][20]

A full-sized coconut fruit weighs about 1.4 kilograms (3 pounds 1 ounce). Coconuts sold domestically in coconut-producing countries are typically not de-husked. Especially immature coconuts (6 to 8 months from flowering) are sold for coconut water and softer jelly-like coconut meat (known as "green coconuts", "young coconuts", or "water coconuts" ), where the original coloration of the fruit is more aesthetically pleasing.[21][22]

Whole mature coconuts (11 to 13 months from flowering) sold for export, however, typically have the husk removed to reduce weight and volume for transport. This results in the naked coconut "shell" with three pores more familiar in countries where coconuts are not grown locally. De-husked coconuts typically weigh around 750 to 850 grams (1 lb 10 oz to 1 lb 14 oz).De-huskedcoconuts are also easier for consumers to open, but have a shorter postharvest storage life of around two to three weeks at temperatures of 12 to 15 °C (54 to 59 °F) or up to 2 months at 0 to 1.5 °C (32.0 to 34.7 °F). In comparison, mature coconuts with the husk intact can be stored for three to five months at normal room temperature.[21][22]

Roots

Unlike some other plants, thepalm treehas neither ataprootnorroot hairs,but has afibrous root system.[23]The root system consists of an abundance of thin roots that grow outward from the plant near the surface. Only a few of the roots penetrate deep into the soil for stability. This type of root system is known as fibrous or adventitious, and is a characteristic of grass species. Other types of large trees produce a single downward-growing tap root with a number of feeder roots growing from it. 2,000–4,000adventitious rootsmay grow, each about1 cm (1⁄2in) large. Decayed roots are replaced regularly as the tree grows new ones.[24]

Inflorescence

The palm produces both the female and maleflowerson the sameinflorescence;thus, the palm ismonoecious.[23]However, there is some evidence that it may bepolygamomonoeciousand may occasionally have bisexual flowers.[25]The female flower is much larger than the male flower. Flowering occurs continuously. Coconut palms are believed to be largely cross-pollinated,although most dwarf varieties are self-pollinating.[20]

Taxonomy

Phylogeny

Theevolutionary historyandfossildistribution ofCocos nuciferaand other members of the tribeCocoseaeis more ambiguous than modern-day dispersal and distribution, with its ultimate origin and pre-human dispersal still unclear. There are currently two major viewpoints on the origins of the genusCocos,one in the Indo-Pacific, and another in South America.[26][27]The vast majority ofCocos-like fossils have been recovered generally from only two regions in the world:New Zealandand west-centralIndia.However, like most palm fossils,Cocos-like fossils are still putative, as they are usually difficult to identify.[27] The earliestCocos-like fossil to be found wasCocos zeylandica,a fossil species described as small fruits, around3.5 cm (1+1⁄2in) ×1.3 to 2.5 cm (1⁄2to 1 in) in size, recovered from theMiocene(~23 to 5.3 million years ago) ofNew Zealandin 1926. Since then, numerous other fossils of similar fruits were recovered throughout New Zealand from theEocene,Oligocene,and possibly theHolocene.But research on them is still ongoing to determine their phylogenetic affinities.[27][28]Endt & Hayward (1997) have noted their resemblance to members of the South American genusParajubaea,rather thanCocos,and propose a South American origin.[27][29][30]Conranet al.(2015), however, suggests that their diversity in New Zealand indicate that they evolved endemically, rather than being introduced to the islands by long-distance dispersal.[28]In west-central India, numerous fossils ofCocos-like fruits, leaves, and stems have been recovered from theDeccan Traps.They includemorphotaxalikePalmoxylon sundaran,Palmoxylon insignae,andPalmocarpon cocoides.Cocos-like fossils of fruits includeCocos intertrappeansis,Cocos pantii,andCocos sahnii.They also include fossil fruits that have been tentatively identified as modernCocos nucifera.These include two specimens namedCocos palaeonuciferaandCocos binoriensis,both dated by their authors to theMaastrichtian–Danianof the earlyTertiary(70 to 62 million years ago).C. binoriensishas been claimed by their authors to be the earliest known fossil ofCocos nucifera.[26][27][31]

Outside of New Zealand and India, only two other regions have reportedCocos-like fossils, namelyAustraliaandColombia.In Australia, aCocos-like fossil fruit, measuring10 cm × 9.5 cm (3+7⁄8in ×3+3⁄4in), were recovered from the Chinchilla Sand Formation dated to the latestPlioceneor basalPleistocene.Rigby (1995) assigned them to modernCocos nuciferabased on its size.[26][27]In Colombia, a singleCocos-like fruit was recovered from themiddle to late PaleoceneCerrejón Formation.The fruit, however, was compacted in the fossilization process and it was not possible to determine if it had the diagnostic three pores that characterize members of the tribeCocoseae.Nevertheless, Gomez-Navarroet al.(2009), assigned it toCocosbased on the size and the ridged shape of the fruit.[32]

Further complicating measures to determine the evolutionary history ofCocosis the genetic diversity present withinC. nuciferaas well as its relatedness to other palms. Phylogenetic evidence supports the closest relatives ofCocosbeing eitherSyagrusorAttalea,both of which are found in South America. However,Cocosis not thought to be indigenous to South America, and the highest genetic diversity is present in AsianCocos,indicating that at least the modern speciesCocos nuciferais native to there.In addition, fossils of potentialCocosancestors have been recovered from both Colombia and India. In order to resolve this Enigma, a 2014 study proposed that the ancestors ofCocoshad likely originated on theCaribbeancoast of what is now Colombia, and during theEocenethe ancestralCocosperformed a long-distance dispersal across theAtlantic OceantoNorth Africa.From here, island-hopping viacoral atollslining theTethys Sea,potentially boosted by ocean currents at the time, would have proved crucial to dispersal, eventually allowing ancestral coconuts to reach India. The study contended that an adaptation to coral atolls would explain the prehistoric and modern distributions ofCocos,would have provided the necessary evolutionary pressures, and would account for morphological factors such as a thick husk to protect against ocean degradation and provide a moist medium in which to germinate on sparse atolls.[33]

Etymology

The namecoconutis derived from the 16th-centuryPortuguesewordcoco,meaning 'head' or 'skull' after the three indentations on the coconut shell that resemble facial features.[34][35][36][37]Cocoandcoconutapparently came from 1521 encounters byPortugueseandSpanishexplorers withPacific Islanders,with the coconut shell reminding them of aghostorwitchin Portuguese folklore calledcoco(alsocôca).[37][38]In the West it was originally callednux indica,a name used byMarco Poloin 1280 while inSumatra.He took the term from the Arabs, who called it جوز هنديjawz hindī,translating to 'Indian nut'.[39]Thenga,itsTamil/Malayalamname, was used in the detailed description of coconut found inItinerariobyLudovico di Varthemapublished in 1510 and also in the laterHortus Indicus Malabaricus.[40]

Carl Linnaeusfirst wanted to name the coconut genusCoccusfromlatinizingthe Portuguese wordcoco,because he saw works by other botanists in middle of the 17th century use the name as well. He consulted the catalogueHerbarium AmboinensebyGeorg Eberhard Rumphiuswhere Rumphius said thatcoccuswas ahomonymofcoccumandcoccusfromGreekκόκκοςkokkosmeaning "grain"[41]or "berry", butRomansidentifiedcoccuswith "kermes insects";Rumphius preferred the wordcocusas a replacement. However, the wordcocuscould also mean "cook" likecoquusin Latin,[42]so Linnaeus choseCocosdirectly from the Portuguese wordcocoinstead.[43]

Thespecific namenuciferais derived from theLatinwordsnux(nut) andfera(bearing), for 'nut-bearing'.[44]

Distribution and habitat

Coconuts have a nearly cosmopolitan distribution due to human cultivation and dispersal. However, their original distribution was in theCentral Indo-Pacific,in the regions ofMaritime Southeast AsiaandMelanesia.[45]

Origin

Modern genetic studies have identified the center of origin of coconuts as being theCentral Indo-Pacific,the region between westernSoutheast AsiaandMelanesia,where it shows greatest genetic diversity.[45][24][48][49]Their cultivation and spread was closely tied to the early migrations of theAustronesian peopleswho carried coconuts ascanoe plantsto the islands they settled.[48][49][50][51]The similarities of the local names in theAustronesianregion is also cited as evidence that the plant originated in the region. For example, thePolynesianandMelanesiantermniu;TagalogandChamorrotermniyog;and theMalaywordnyiurornyior.[52][53]Other evidence for aCentral Indo-Pacificorigin is the native range of thecoconut crab;and the higher amounts ofC. nucifera-specific insect pests in the region (90%) in comparison to the Americas (20%), and Africa (4%).[5]

A study in 2011 identified two highly genetically differentiated subpopulations of coconuts, one originating fromIsland Southeast Asia(the Pacific group) and the other from the southern margins of theIndian subcontinent(the Indo-Atlantic group). The Pacific group is the only one to display clear genetic and phenotypic indications that they were domesticated; including dwarf habit, self-pollination, and the round "niu vai"fruit morphology with larger endosperm-to-husk ratios. The distribution of the Pacific coconuts correspond to regions settled by Austronesian voyagers indicating that its spread was largely the result of human introductions. It is most strikingly displayed inMadagascar,an island settled by Austronesian sailors at around 2000 to 1500BP.The coconut populations on the island show genetic admixture between the two subpopulations indicating that Pacific coconuts were first brought by the Austronesian settlers, which then interbred with the later Indo-Atlantic coconuts brought by Europeans from India.[49][50]

Genetic studies of coconuts have also confirmedpre-Columbianpopulations of coconuts inPanamain South America. However, it is not native and displays a genetic bottleneck resulting from afounder effect.A study in 2008 showed that the coconuts in the Americas are genetically closest related to the coconuts in thePhilippines,and not to any other nearby coconut populations (includingPolynesia). Such an origin indicates that the coconuts were not introduced naturally, such as by sea currents. The researchers concluded that it was brought by early Austronesian sailors to the Americas from at least 2,250 BP, and may be proof of pre-Columbian contact between Austronesian cultures and South American cultures. It is further strengthened by other similar botanical evidence of contact, like the pre-colonial presence ofsweet potatoin Oceanian cultures.[48][51][57]During thecolonial era,Pacific coconuts were further introduced toMexicofrom theSpanish East Indiesvia theManila galleons.[49]

In contrast to the Pacific coconuts, Indo-Atlantic coconuts were largely spread by Arab and Persian traders into theEast Africancoast. Indo-Atlantic coconuts were also introduced into theAtlantic OceanbyPortugueseships from their colonies in coastalIndiaandSri Lanka;first introduced to coastalWest Africa,then onwards into theCaribbeanand the east coast ofBrazil.All of these introductions are within the last few centuries, relatively recent in comparison to the spread of Pacific coconuts.[49]

Natural habitat

The coconut palm thrives on sandy soils and is highly tolerant ofsalinity.It prefers areas with abundant sunlight and regular rainfall (1,500–2,500 mm [59–98 in] annually), which makes colonizing shorelines of the tropics relatively straightforward.[58]Coconuts also need highhumidity(at least 70–80%) for optimum growth, which is why they are rarely seen in areas with low humidity. However, they can be found in humid areas with low annual precipitation such as inKarachi,Pakistan,which receives only about250 mm (9+3⁄4in) of rainfall per year, but is consistently warm and humid.

Coconut palms require warm conditions for successful growth, and are intolerant of cold weather. Some seasonal variation is tolerated, with good growth where mean summer temperatures are between 28 and 37 °C (82 and 99 °F), and survival as long as winter temperatures are above 4–12 °C (39–54 °F); they will survive brief drops to 0 °C (32 °F). Severe frost is usually fatal, although they have been known to recover from temperatures of −4 °C (25 °F). Due to this, there are not manycoconut palms in California.[58]They may grow but not fruit properly in areas with insufficient warmth or sunlight, such asBermuda.

The conditions required for coconut trees to grow without any care are:

- Mean daily temperature above 12–13 °C (54–55 °F) every day of the year

- Mean annual rainfall above 1,000 mm (39 in)

- No or very little overheadcanopy,since even small trees require direct sun

The main limiting factor for most locations which satisfy the rainfall and temperature requirements is canopy growth, except those locations near coastlines, where the sandy soil and salt spray limit the growth of most other trees.

Domestication

Wild coconuts are naturally restricted to coastal areas in sandy, saline soils. The fruit is adapted for ocean dispersal. Coconuts could not reach inland locations without human intervention (to carry seednuts, plant seedlings, etc.) and early germination on the palm (vivipary) was important.[59]

Coconuts today can be grouped into two highly genetically distinct subpopulations: the Indo-Atlantic group originating from southernIndiaand nearby regions (includingSri Lanka,theLaccadives,and theMaldives); and the Pacific group originating from the region betweenmaritime Southeast AsiaandMelanesia.Linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence all point to the early domestication of Pacific coconuts by theAustronesian peoplesin maritime Southeast Asia during theAustronesian expansion(c. 3000 to 1500 BCE). Although archaeological remains dating to 1000 to 500 BCE also suggest that the Indo-Atlantic coconuts were also later independently cultivated by theDravidian peoples,only Pacific coconuts show clear signs of domestication traits like dwarf habits, self-pollination, and rounded fruits. Indo-Atlantic coconuts, in contrast, all have the ancestral traits of tall habits and elongated triangular fruits.[49][5][48][60]

The coconut played a critical role in the migrations of the Austronesian peoples. They provided a portable source of both food and water, allowing Austronesians to survive long sea voyages to colonize new islands as well as establish long-range trade routes. Based on linguistic evidence, the absence of words for coconut in the Taiwanese Austronesian languages makes it likely that the Austronesian coconut culture developed only after Austronesians started colonizing thePhilippine islands.The importance of the coconut in Austronesian cultures is evidenced by shared terminology of even very specific parts and uses of coconuts, which were carried outwards from the Philippines during the Austronesian migrations.[49][5]Indo-Atlantic type coconuts were also later spread byArabandSouth Asiantraders along theIndian Oceanbasin, resulting in limited admixture with Pacific coconuts introduced earlier toMadagascarand theComorosvia the ancientAustronesian maritime trade network.[49]

Coconuts can be broadly divided into two fruit types – the ancestralniu kafaform with a thick-husked, angular fruit, and theniu vaiform with a thin-husked, spherical fruit with a higher proportion ofendosperm.The terms are derived from theSamoan languageand was adopted into scientific usage by Harries (1978).[49][18][61]

Theniu kafaform is the wild ancestral type, with thick husks to protect the seed, an angular, highly ridged shape to promote buoyancy during ocean dispersal, and a pointed base that allowed fruits to dig into the sand, preventing them from being washed away duringgerminationon a new island. It is the dominant form in the Indo-Atlantic coconuts.[18][49]However, they may have also been partially selected for thicker husks forcoirproduction, which was also important in Austronesian material culture as a source for cordage in building houses and boats.[5]

Theniu vaiform is the domesticated form dominant in Pacific coconuts. They were selected for by the Austronesian peoples for their larger endosperm-to-husk ratio as well as higher coconut water content, making them more useful as food and water reserves for sea voyages. The decreased buoyancy and increased fragility of this spherical, thin-husked fruit would not matter for a species that had started to be dispersed by humans and grown in plantations.[18][19]Niu vaiendocarp fragments have been recovered in archaeological sites in theSt. Matthias Islandsof theBismarck Archipelago.The fragments are dated to approximately 1000 BCE, suggesting that cultivation and artificial selection of coconuts were already practiced by the AustronesianLapita people.[5]

Coconuts can also be broadly divided into two general types based on habit: the "Tall" (var.typica) and "Dwarf" (var.nana) varieties.[62]The two groups are genetically distinct, with the dwarf variety showing a greater degree of artificial selection for ornamental traits and for early germination and fruiting.[61][63]The tall variety isoutcrossingwhile dwarf palms areself-pollinating,which has led to a much greater degree ofgenetic diversitywithin the tall group.[64]

The dwarf coconut cultivars are fully domesticated, in contrast to tall cultivars which display greater diversity in terms of domestication (and lack thereof).[65][64]The fact that all dwarf coconuts share three genetic markers out of thirteen (which are only present at low frequencies in tall cultivars) makes it likely that they all originate from a single domesticated population. Philippine and Malayan dwarf coconuts diverged early into two distinct types. They usually remain genetically isolated when introduced to new regions, making it possible to trace their origins. Numerous other dwarf cultivars also developed as the initial dwarf cultivar was introduced to other regions and hybridized with various tall cultivars. The origin of dwarf varieties isSoutheast Asia,which contain the tall cultivars that are genetically closest to dwarf coconuts.[49][11][65][64]

Sequencing of the genome of the tall and dwarf varieties revealed that they diverged 2 to 8 million years ago and that the dwarf variety arose through alterations in genes involved in the metabolism of the plant hormonegibberellin.[66]

Another ancestral variety is theniu lekaofPolynesia(sometimes called the "Compact Dwarfs" ). Although it shares similar characteristics to dwarf coconuts (including slow growth), it is genetically distinct and is thus believed to be independently domesticated, likely inTonga.Other cultivars ofniu lekamay also exist in other islands of the Pacific, and some are probably descendants of advanced crosses between Compact Dwarfs and Southeast Asian Dwarf types.[11][65]

Dispersal

Coconut fruit in the wild is light, buoyant, and highly water resistant. It is claimed that they evolved to disperse significant distances viamarine currents.[67]However, it can also be argued that the placement of the vulnerable eye of the nut (down when floating), and the site of the coir cushion are better positioned to ensure that the water-filled nut does not fracture when dropping on rocky ground, rather than for flotation.

It is also often stated that coconuts can travel 110 days, or 5,000 km (3,000 mi), by sea and still be able to germinate.[68]This figure has been questioned based on the extremely small sample size that forms the basis of the paper that makes this claim.[57]Thor Heyerdahlprovides an alternative, and much shorter, estimate based on his first-hand experience crossing the Pacific Ocean on the raftKon-Tiki:[69]

The nuts we had in baskets on deck remained edible and capable of germinating the whole way toPolynesia.But we had laid about half among the special provisions below deck, with the waves washing around them. Every single one of these was ruined by the sea water. And no coconut can float over the sea faster than abalsaraft moves with the wind behind it.

He also notes that several of the nuts began to germinate by the time they had been ten weeks at sea, precluding an unassisted journey of 100 days or more.[57]

Drift models based on wind and ocean currents have shown that coconuts could not have drifted across the Pacific unaided.[57]If they were naturally distributed and had been in the Pacific for a thousand years or so, then we would expect the eastern shore of Australia, with its own islands sheltered by theGreat Barrier Reef,to have been thick with coconut palms: the currents were directly into, and down along this coast. However, bothJames CookandWilliam Bligh[70](put adrift after theBountymutiny) found no sign of the nuts along this 2,000 km (1,200 mi) stretch when he needed water for his crew. Nor were there coconuts on the east side of the African coast untilVasco da Gama,nor in the Caribbean when first visited byChristopher Columbus.They were commonly carried by Spanish ships as a source of fresh water.

These provide substantial circumstantial evidence that deliberateAustronesianvoyagers were involved in carrying coconuts across the Pacific Ocean and that they could not have dispersed worldwide without human agency. More recently, genomic analysis of cultivated coconut (C. nuciferaL.) has shed light on the movement. However,admixture,the transfer of genetic material, evidently occurred between the two populations.[71]

Given that coconuts are ideally suited for inter-island group ocean dispersal, obviously some natural distribution did take place. However, the locations of the admixture events are limited toMadagascarand coastal east Africa, and exclude theSeychelles.This pattern coincides with the known trade routes of Austronesian sailors. Additionally, a genetically distinct subpopulation of coconut on the Pacific coast of Latin America has undergone a genetic bottleneck resulting from afounder effect;however, its ancestral population is the Pacific coconut from the Philippines. This, together with their use of the South Americansweet potato,suggests that Austronesian peoples may have sailed as far east as the Americas.[71]In theHawaiian Islands,the coconut is regarded as aPolynesianintroduction,first brought to the islands by early Polynesian voyagers (also Austronesians) from their homelands in the southern islands of Polynesia.[39]

Specimens have been collected from the sea as far north asNorway(but it is not known where they entered the water).[72]They have been found in the Caribbean and the Atlantic coasts of Africa and South America for less than 500 years (the Caribbean native inhabitants do not have a dialect term for them, but use the Portuguese name), but evidence of their presence on the Pacific coast of South America antedates Columbus's arrival in the Americas.[45]They are now almost ubiquitous between 26° N and 26° S except for the interiors of Africa and South America.

The 2014 coral atoll origin hypothesis proposed that the coconut had dispersed in an island hopping fashion using the small, sometimes transient, coral atolls. It noted that by using these small atolls, the species could easily island-hop. Over the course of evolutionary time-scales the shifting atolls would have shortened the paths of colonization, meaning that any one coconut would not have to travel very far to find new land.[33]

Ecology

Coconuts are susceptible to thephytoplasmadisease,lethal yellowing.One recently selectedcultivar,the'Maypan',has been bred for resistance to this disease.[73]Yellowing diseases affect plantations in Africa, India, Mexico, the Caribbean and thePacific Region.[74]Konanet al.,2007 explains muchresistancewith a fewallelesat a fewmicrosatellites.[75]They find that 'Vanuatu Tall' and 'Sri-Lanka Green Dwarf' are the most resistant while 'West African Tall' breeds are especially susceptible.[75]

The coconut palm is damaged by thelarvaeof manyLepidoptera(butterflyandmoth) species which feed on it, including theAfrican armyworm(Spodoptera exempta) andBatrachedraspp.:B. arenosella,B. atriloqua(feeds exclusively onC. nucifera),B. mathesoni(feeds exclusively onC. nucifera), andB. nuciferae.[76]

Brontispa longissima(coconut leaf beetle) feeds on young leaves, and damages bothseedlingsand mature coconut palms. In 2007, the Philippines imposed aquarantineinMetro Manilaand 26 provinces to stop the spread of thepestand protect the Philippine coconut industry managed by some 3.5 million farmers.[77]

The fruit may also be damaged byeriophyidcoconut mites(Eriophyes guerreronis). This mite infests coconut plantations, and is devastating; it can destroy up to 90% of coconut production. The immature seeds are infested and desapped by larvae staying in the portion covered by theperianthof the immature seed; the seeds then drop off or survive deformed. Spraying with wettablesulfur0.4% or withNeem-based pesticides can give some relief, but is cumbersome and labor-intensive.

In Kerala, India, the main coconut pests are thecoconut mite,therhinoceros beetle,thered palm weevil,and thecoconut leaf caterpillar.Research into countermeasures to these pests has as of 2009[update]yielded no results; researchers from theKerala Agricultural Universityand the Central Plantation Crop Research Institute, Kasaragode, continue to work on countermeasures. The Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Kannur under Kerala Agricultural University has developed an innovative extension approach called the compact area group approach to combat coconut mites.

Production and cultivation

| Country | Production (millions oftonnes) |

|---|---|

| 17.2 | |

| 14.9 | |

| 13.3 | |

| 2.7 | |

| 2.2 | |

| World | 62.4 |

| Source:FAOSTATof theUnited Nations[78] | |

In 2022, world production of coconuts was 62 milliontonnes,led byIndonesia,India, and the Philippines, with 73% combined of the total (table).[78]

Cultivation

Coconut palms are normally cultivated in hot and wet tropical climates. They need year-round warmth and moisture to grow well and fruit. Coconut palms are hard to establish in dry climates, and cannot grow there without frequent irrigation; in drought conditions, the new leaves do not open well, and older leaves may become desiccated; fruit also tends to be shed.[58]

The extent of cultivation in the tropics is threatening a number of habitats, such asmangroves;an example of such damage to an ecoregion is in the Petenes mangroves of theYucatán.[79]

Unique among plants, coconut trees can be irrigated with sea water.[80]

Cultivars

Coconut has a number of commercial and traditionalcultivars.They can be sorted mainly into tall cultivars, dwarf cultivars, and hybrid cultivars (hybrids between talls and dwarfs). Some of the dwarf cultivars such as 'Malayan dwarf' have shown some promising resistance to lethal yellowing, while other cultivars such as 'Jamaican tall' are highly affected by the same plant disease. Some cultivars are more drought resistant such as 'West coast tall' (India) while others such as 'Hainan Tall' (China) are more cold tolerant. Other aspects such as seed size, shape and weight, andcoprathickness are also important factors in the selection of new cultivars. Some cultivars such as 'Fiji dwarf' form a large bulb at the lower stem and others are cultivated to produce very sweet coconut water with orange-colored husks (king coconut) used entirely in fruit stalls for drinking (Sri Lanka, India).[citation needed]

Harvesting

Center:Worker harvesting coconuts inVeracruz,Mexicousing ropes andpulleys;

Right:Coconut workers in theMaldivesusing a loop of cloth around the ankles

The two most common harvesting methods are the climbing method and the pole method. Climbing is the most widespread, but it is also more dangerous and requires skilled workers.[81]Manually climbing trees is traditional in most countries and requires a specific posture that exerts pressure on the trunk with the feet. Climbers employed on coconut plantations often develop musculoskeletal disorders and risk severe injury or death from falling.[82][83][84]

To avoid this, coconuts workers in the Philippines andGuamtraditionally usebolostied with a rope to the waist to cut grooves at regular intervals on the coconut trunks. This basically turns the trunk of the tree into a ladder, though it reduces the value of coconut timber recovered from the trees and can be an entry point for infection.[85][81][86]Other manual methods to make climbing easier include using a system of pulleys and ropes; using pieces of vine, rope, or cloth tied to both hands or feet; using spikes attached to the feet or legs; or attaching coconut husks to the trunk with ropes.[87]Modern methods use hydraulic elevators mounted on tractors or ladders.[88]Mechanical coconut climbing devices and even automated robots have also been recently developed in countries like India, Sri Lanka, andMalaysia.[89][90][91][87]

The pole method uses a long pole with a cutting device at the end. In the Philippines, the traditional tool is known as thehalabasand is made from a long bamboo pole with a sickle-like blade mounted at the tip. Though safer and faster than the climbing method, its main disadvantage is that it does not allow workers to examine and clean the crown of coconuts for pests and diseases.[92]

Determiningwhetherto harvest is also important. Gatchalian et al. 1994 developed asonometrytechnique for precisely determining the stage of ripeness of young coconuts.[93]

A system of bamboo bridges and ladders directly connecting the tree canopies are also utilized in the Philippines for coconut plantations that harvest coconut sap (not fruits) forcoconut vinegarandpalm wineproduction.[94][88]In other areas, like inPapua New Guinea,coconuts are simply collected when they fall to the ground.[81]

A more controversial method employed by a small number of coconut farmers inThailandand Malaysia use trainedpig-tailed macaquesto harvest coconuts. Thailand has been raising and training pig-tailed macaques to pick coconuts for around 400 years.[95][96][97]Training schools for pig-tailed macaques still exist both in southern Thailand and in the Malaysian state ofKelantan.[98]

The practice of using macaques to harvest coconuts was exposed inThailandby thePeople for the Ethical Treatment of Animals(PETA) in 2019, resulting in calls forboycottson coconut products. PETA later clarified that the use of macaques is not practiced in the Philippines, India,Brazil,Colombia,Hawaii,and other major coconut-producing regions.[88]

Substitutes for cooler climates

In cooler climates (but not less thanUSDA Zone 9), a similar palm, thequeen palm(Syagrus romanzoffiana), is used inlandscaping.Its fruits are similar to coconut, but smaller. The queen palm was originally classified in the genusCocosalong with the coconut, but was later reclassified inSyagrus.A recently discovered palm,Beccariophoenix alfrediifromMadagascar,is nearly identical to the coconut, more so than the queen palm and can also be grown in slightly cooler climates than the coconut palm. Coconuts can only be grown in temperatures above 18 °C (64 °F) and need a daily temperature above 22 °C (72 °F) to produce fruit.[citation needed]

Production by country

Indonesia

Indonesia is the world's largest producer of coconuts, with a gross production of 15 million tonnes.[99]

Philippines

The Philippines is the world's second-largest producer of coconuts. It was the world's largest producer for decades until a decline in production due to aging trees as well as from typhoon devastations. Indonesia overtook it in 2010. It is still the largest producer ofcoconut oilandcopra,accounting for 64% of global production. The production of coconuts plays an important role in theeconomy,with 25% of cultivated land (around 3.56 million hectares) used for coconut plantations and approximately 25 to 33% of the population reliant on coconuts for their livelihood.[100][101][102]

Two important coconut products were first developed in the Philippines,MacapunoandNata de coco.Macapuno is a coconut variety with a jelly-like coconut meat. Its meat is sweetened, cut into strands, and sold in glass jars as coconut strings, sometimes labeled as "coconut sport".Nata de coco,also called coconut gel, is another jelly-like coconut product made from fermented coconut water.[103][104]

India

Traditional areas of coconut cultivation in India are the states ofKerala,Tamil Nadu,Karnataka,Puducherry,Andhra Pradesh,Goa,Maharashtra,Odisha,West Bengaland,Gujaratand the islands ofLakshadweepandAndaman and Nicobar.As per 2014–15 statistics from Coconut Development Board of Government of India, four southern states combined account for almost 90% of the total production in the country: Tamil Nadu (33.8%), Karnataka (25.2%), Kerala (24.0%), and Andhra Pradesh (7.2%).[105]Other states, such as Goa, Maharashtra, Odisha, West Bengal, and those in the northeast (TripuraandAssam) account for the remaining productions. Though Kerala has the largest number of coconut trees, in terms of production per hectare, Tamil Nadu leads all other states. In Tamil Nadu,CoimbatoreandTirupurregions top the production list.[106]The coconut tree is the official state tree of Kerala, India.

In Goa, the coconut tree has been reclassified by the government as a palm (rather than a tree), enabling farmers and developers to clear land with fewer restrictions and without needing permission from the forest department before cutting a coconut tree.[107][108]

Middle East

This sectionpossibly containsoriginal research.(April 2024) |

The main coconut-producing area in the Middle East is theDhofarregion ofOman,but they can be grown all along thePersian Gulf,Arabian Sea,andRed Seacoasts, because these seas are tropical and provide enough humidity (through seawater evaporation) for coconut trees to grow. The young coconut plants need to be nursed and irrigated with drip pipes until they are old enough (stem bulb development) to be irrigated withbrackish wateror seawater alone, after which they can be replanted on the beaches. In particular, the area aroundSalalahmaintains large coconut plantations similar to those found across the Arabian Sea in Kerala. The reasons why coconut are cultivated only inYemen'sAl MahrahandHadramautgovernorates and in the Sultanate of Oman, but not in other suitable areas in theArabian Peninsula,may originate from the fact that Oman and Hadramaut had longdhowtrade relations withBurma,Malaysia, Indonesia, East Africa, andZanzibar,as well as southern India and China. Omani people needed the coir rope from the coconut fiber to stitch together their traditional seagoingdhowvessels in which nails were never used. The know-how of coconut cultivation and necessarysoil fixationandirrigationmay have found its way into Omani, Hadrami and Al-Mahra culture by people who returned from those overseas areas.

The ancient coconut groves of Dhofar were mentioned by the medieval Moroccan travellerIbn Battutain his writings, known asAlRihla.[109]The annual rainy season known locally askhareeformonsoonmakes coconut cultivation easy on the Arabian east coast.

Coconut trees also are increasingly grown for decorative purposes along the coasts of theUnited Arab EmiratesandSaudi Arabiawith the help of irrigation. The UAE has, however, imposed strict laws on mature coconut tree imports from other countries to reduce the spread ofpeststo other native palm trees, as the mi xing of date and coconut trees poses a risk of cross-species palm pests, such asrhinoceros beetlesandred palm weevils.[110]The artificial landscaping may have been the cause forlethal yellowing,a viral coconut palm disease that leads to the death of the tree. It is spread by host insects that thrive on heavy turf grasses. Therefore, heavy turf grass environments (beach resortsandgolf courses) also pose a major threat to local coconut trees. Traditionally,dessert bananaplants and local wild beach flora such asScaevola taccadaandIpomoea pes-capraewere used as humidity-supplying green undergrowth for coconut trees, mixed withsea almondandsea hibiscus.Due to growingsedentary lifestylesand heavy-handed landscaping, a decline in these traditional farming and soil-fi xing techniques has occurred.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lankais the world's fourth-largest producer of coconuts and is the second-largest producer of coconut oil and copra, accounting for 15% of the global production.[111]The production of coconuts is the main source ofSri Lanka economy,with 12% of cultivated land and 409,244 hectares used for coconut growing (2017). Sri Lanka established its Coconut Development Authority and Coconut Cultivation Board and Coconut Research Institute in the earlyBritish Ceylonperiod.[111]

United States

In theUnited States,coconut palms can be grown and reproduced outdoors without irrigation inHawaii,southern and centralFlorida,[112]and the territories ofPuerto Rico,Guam,American Samoa,theU.S. Virgin Islands,and theNorthern Mariana Islands.Coconut palms are also periodically successful in theLower Rio Grande Valleyregion ofsouthern Texasand in other microclimates in thesouthwest.

InFlorida,wild populations of coconut palms extend up the East Coast fromKey WesttoJupiter Inlet,and up the West Coast fromMarco IslandtoSarasota.Many of the smallest coral islands in theFlorida Keysare known to have abundant coconut palms sprouting from coconuts that have drifted or been deposited by ocean currents. Coconut palms are cultivated north of South Florida to roughlyCocoa Beachon the East Coast andClearwateron the West Coast.

Australia

Coconuts are commonly grown around the northern coast of Australia, and in some warmer parts ofNew South Wales.However, they are mainly present as decoration, and the Australian coconut industry is small; Australia is a net importer of coconut products. Australian cities put much effort into de-fruiting decorative coconut trees to ensure that mature coconuts do not fall and injure people.[113]

Allergens

Food

Coconut oilis increasingly used in the food industry.[114]Proteins from coconutmay cause allergic reactions,includinganaphylaxis,in some people.[114]

In the United States, theFood and Drug Administrationdeclared that coconut must be disclosed as an ingredient on package labels as a "tree nut" with potentialallergenicity.[115]

Topical

Cocamidopropyl betaine(CAPB) is asurfactantmanufactured from coconut oil that is increasingly used as an ingredient in personal hygiene products and cosmetics, such asshampoos,liquidsoaps,cleansers andantiseptics,among others.[116]CAPB may cause mild skin irritation,[116]but allergic reactions to CAPB are rare[117]and probably related to impurities rendered during the manufacturing process (which includeamidoamineanddimethylaminopropylamine) rather than CAPB itself.[116]

Uses

The coconut palm is grown throughout thetropicsfor decoration, as well as for its many culinary and nonculinary uses; virtually every part of the coconut palm can be used by humans in some manner and has significant economic value. Coconuts' versatility is sometimes noted in its naming. InSanskrit,it iskalpa vriksha( "the tree which provides all the necessities of life" ). In theMalay language,it ispokok seribu guna( "the tree of a thousand uses" ). In the Philippines, the coconut is commonly called the "tree of life".[118]

It is one of the most useful trees in the world.[16]

Culinary

Nutrition

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,480 kJ (350 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15.23 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 6.23 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 9.0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

33.49 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 29.698 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 1.425 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 0.366 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3.33 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 0.039 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 0.121 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 0.131 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 0.247 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 0.147 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 0.062 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cystine | 0.066 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 0.169 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 0.103 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 0.202 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 0.546 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.077 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 0.170 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 0.325 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 0.761 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 0.158 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 0.138 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 0.172 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 47 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[119]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[120] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference serving of raw coconut flesh supplies 1,480 kilojoules (354 kilocalories) offood energyand a high amount of totalfat(33 grams), especiallysaturated fat(89% of total fat), along with a moderate quantity ofcarbohydrates(15g), andprotein(3g).Micronutrientsin significant content (more than 10% of theDaily Value) include thedietary minerals,manganese,copper,iron,phosphorus,selenium,andzinc(table).

Coconut meat

The edible white, fleshy part of the seed (theendosperm) is known as the "coconut meat", "coconut flesh", or "coconut kernel".[121]In the coconut industry, coconut meat can be classified loosely into three different types depending on maturity – namely"Malauhog", "Malakanin" and "Malakatad".The terminology is derived from theTagalog language.Malauhog (literally "mucus-like ") refers to very young coconut meat (around 6 to 7 months old) which has a translucent appearance and a gooey texture that disintegrates easily. Malakanin (literally"cooked rice-like ") refers to young coconut meat (around 7–8 months old) which has a more opaque white appearance, a soft texture similar to cooked rice, and can still be easily scraped off the coconut shell. Malakatad (literally" leather-like ") refers to fully mature coconut meat (around 8 to 9 months old) with an opaque white appearance, a tough rubbery to leathery texture, and is difficult to separate from the shell.[122][123]

Maturity is difficult to assess on an unopened coconut, and there is no technically proven method for determining maturity. Based on color and size, younger coconuts tend to be smaller and have brighter colors, while more mature coconuts have browner colors and are larger.[124]They can also be determined traditionally by tapping on the coconut fruit. Malauhog has a "solid" sound when tapped, while Malakanin and Malakatad produce a "hollow" sound.[122][123]Another method is to shake the coconut. Immature coconuts produce a sloshing sound when shaken (the sharper the sound, the younger it is), while fully mature coconuts do not.[125][126]

Both"Malauhog"and"Malakanin"meats of immature coconuts can be eaten as is or used in salads, drinks, desserts, and pastries such asbuko pieandes kelapa muda.Because of their soft textures, they are unsuitable for grating. Mature Malakatad coconut meat has a tough texture and thus is processed before consumption or made intocopra.Freshly shredded mature coconut meat, known as "grated coconut", "shredded coconut", or "coconut flakes", is used in the extraction ofcoconut milk.They are also used as agarnishfor various dishes, as inkleponandputo bumbong.They can also be cooked in sugar and eaten as a dessert in the Philippines known asbukayo.[121][127][128][129][130]

Grated coconut that is dehydrated by drying or baking is known as "desiccated coconut". It contains less than 3% of the original moisture content of coconut meat. It is predominantly used in thebakeryandconfectioneryindustries (especially in non-coconut-producing countries) because of its longer shelf life compared to freshly grated coconut.[131][132][133]Desiccated coconut is used in confections and desserts such asmacaroons.Dried coconut is also used as the filling for manychocolate bars.Some dried coconut is purely coconut, but others are manufactured with other ingredients, such assugar,propylene glycol,salt,andsodium metabisulfite.

Coconut meat can also be cut into larger pieces or strips, dried, and salted to make "coconut chips" or "coco chips".[129]These can be toasted or baked to make bacon-like fi xing s.[134]

Macapuno

A special cultivar of coconut known asmacapunoproduces a large amount of jelly-like coconut meat. Its meat fills the entire interior of the coconut shell, rather than just the inner surfaces. It was first developed for commercial cultivation in the Philippines and is used widely inPhilippine cuisinefor desserts, drinks, and pastries. It is also popular inIndonesia(where it is known askopyor) for making beverages.[104]

Coconut milk

Coconut milk, not to be confused with coconut water, is obtained by pressing the grated coconut meat, usually with hot water added which extracts the coconut oil, proteins, and aromatic compounds. It is used for cooking various dishes. Coconut milk contains 5% to 20% fat, while coconut cream contains around 20% to 50% fat.[135][89]Most of the fat issaturated(89%), withlauric acidbeing the majorfatty acid.[136]Coconut milk can be diluted to createcoconut milk beverages.These have a much lower fat content and are suitable asmilk substitutes.[135][89]

Coconut milk powder,a protein-rich powder, can be processed from coconut milk followingcentrifugation,separation,andspray drying.[137]

Coconut milk andcoconut creamextracted from grated coconut is often added to various desserts and savory dishes, as well as incurriesand stews.[138][139]It can also be diluted into a beverage. Various other products made from thickened coconut milk with sugar and/or eggs likecoconut jamandcoconut custardare also widespread in Southeast Asia.[140][141]In the Philippines, sweetened reduced coconut milk is marketed ascoconut syrupand is used for various desserts.[142]Coconut oil extracted from coconut milk or copra is also used forfrying,cooking, and makingmargarine,among other uses.[138][143]

Coconut water

Coconut water serves as a suspension for theendospermof the coconut during itsnuclear phaseof development. Later, the endosperm matures and deposits onto the coconut rind during the cellular phase.[13]The water is consumed throughout the humid tropics, and has been introduced into theretail marketas a processedsports drink.Mature fruits have significantly less liquid than young, immature coconuts, barring spoilage. Coconut water can be fermented to produce coconut vinegar.

Per 100-gram serving, coconut water contains 19caloriesand no significant content ofessential nutrients.

Coconut water can be drunk fresh or used in cooking as inbinakol.[144][145]It can also be fermented to produce a jelly-like dessert known asnata de coco.[103]

Coconut flour

Coconut flour has also been developed for use in baking, to combat malnutrition.[138]

Sprouted coconut

Newly germinated coconuts contain a spherical edible mass known as the sprouted coconut or coconut sprout. It has a crunchy watery texture and a slightly sweet taste. It is eaten as is or used as an ingredient in various dishes. It is produced as theendospermnourishes thedeveloping embryo.It is ahaustorium,a spongy absorbent tissue formed from the distal part of embryo during coconut germination, which facilitates absorption of nutrients for the growing shoot and root.[146]

Heart of palm

Apical budsof adult plants are edible, and are known as "palm cabbage" or heart of palm. They are considered a rare delicacy, as harvesting the buds kills the palms. Hearts of palm are eaten in salads, sometimes called "millionaire's salad".

Toddy and sap

The sap derived from incising the flower clusters of the coconut is drunk astoddy,also known astubâin the Philippines (both fermented and fresh),tuak(Indonesia and Malaysia),karewe(fresh and not fermented, collected twice a day, for breakfast and dinner) inKiribati,andneerainSouth Asia.When left to ferment on its own, it becomes palm wine. Palm wine is distilled to producearrack.In the Philippines, this alcoholic drink is calledlambanog(historically also calledvino de cocoin Spanish) or "coconut vodka".[147]

The sap can be reduced by boiling to create a sweet syrup or candy such aste kamamaiin Kiribati ordhiyaa hakuruandaddu bondiin the Maldives. It can be reduced further to yieldcoconut sugaralso referred to aspalm sugarorjaggery.A young, well-maintained tree can produce around 300 litres (79 US gallons) of toddy per year, while a 40-year-old tree may yield around 400 L (110 US gal).[148]

Coconut sap, usually extracted from cut inflorescence stalks is sweet when fresh and can be drunk as is such as intuba frescaofMexico(derived from the Philippinetubâ).[149]They can also be processed to extract palm sugar.[150]The sap when fermented can also be made into coconut vinegar or various palm wines (which can be furtherdistilledto make arrack).[151][152]

Coconut vinegar

Coconut vinegar, made from fermentedcoconut wateror sap, is used extensively in Southeast Asian cuisine (notably the Philippines, where it is known assukang tuba), as well as in some cuisines of India and Sri Lanka, especiallyGoan cuisine.A cloudy white liquid, it has a particularly sharp, acidic taste with a slightly yeasty note.[127]

Coconut oil

Coconut oil is commonly used in cooking, especially for frying. It can be used in liquid form as would othervegetable oils,or in solid form similar tobutterorlard.

Long-term consumption of coconut oil may have negative health effects similar to those from consuming other sources ofsaturated fats,including butter,beef fat,andpalm oil.[153]Its chronic consumption may increase the risk ofcardiovascular diseasesby raising totalblood cholesterollevels through elevated blood levels ofLDL cholesterolandlauric acid.[154][155]

Coconut butter

Coconut butteris often used to describe solidified coconut oil, but has also been adopted as an alternate name forcreamed coconut,a specialty product made of coconut milk solids orpuréedcoconut meat and oil.[121]Having a creamy Consistency that is spreadable, reminiscent of Peanut butter albeit a little richer.[156]

Copra

Copra is the dried meat of the seed and after processing produces coconut oil and coconut meal. Coconut oil, aside from being used in cooking as an ingredient and for frying, is used in soaps, cosmetics, hair oil, and massage oil. Coconut oil is also a main ingredient inAyurvedic oils.InVanuatu,coconut palms for copra production are generally spaced 9 m (30 ft) apart, allowing a tree density of 100 to 160 per hectare (40 to 65 per acre).

It takes around 6,000 full-grown coconuts to produce one tonne of copra.[157]

Husks and shells

The husk and shells can be used for fuel and are a source ofcharcoal.[158]Activated carbonmanufactured from coconut shell is considered extremely effective for the removal of impurities. The coconut's obscure origin in foreign lands led to the notion of using cups made from the shell to neutralise poisoned drinks. Thecupswere frequently engraved and decorated with precious metals.[159]

The husks can be used asflotation devices.As anabrasive,[160]a dried half coconut shell with husk can be used to buff floors. It is known as abunotin the Philippines and simply a "coconut brush" inJamaica.The fresh husk of a brown coconut may serve as a dish sponge or body sponge. Acoco chocolaterowas a cup used to serve small quantities of beverages (such as chocolate drinks) between the 17th and 19th centuries in countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, and Venezuela.

In Asia, coconut shells are also used as bowls and in the manufacture of various handicrafts, including buttons carved from the dried shell. Coconut buttons are often used for Hawaiianaloha shirts.Tempurung,as the shell is called in the Malay language, can be used as a soup bowl and – if fixed with a handle – a ladle. In Thailand, the coconut husk is used as a potting medium to produce healthy forest treesaplings.The process of husk extraction from the coir bypasses the retting process, using a custom-built coconut husk extractor designed byASEAN–Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre in 1986. Fresh husks contain moretanninthan old husks. Tannin produces negative effects on sapling growth.[161]The shell and husk can be burned for smoke torepelmosquitoes[160]and are used in parts of South India for this purpose.

Half coconut shells are used in theatreFoley sound effectswork, struck together to create the sound effect of a horse's hoofbeats. Dried half shells are used as the bodies of musical instruments, including the Chineseyehuandbanhu,along with the Vietnameseđàn gáoand Arabo-Turkicrebab.In the Philippines, dried half shells are also used as a musical instrument in a folk dance calledmaglalatik.

The shell, freed from the husk, and heated on warm ashes, exudes an oily material that is used to soothe dental pains intraditional medicineof Cambodia.[162]

In World War II,coastwatcherscoutBiuku Gasawas the first of two from theSolomon Islandsto reach the shipwrecked and wounded crew ofMotor Torpedo BoatPT-109commanded by future U.S. presidentJohn F. Kennedy.Gasa suggested, for lack of paper, delivering by dugout canoe a message inscribed on a husked coconut shell, reading "Nauru Isl commander / native knows posit / he can pilot / 11 alive need small boat / Kennedy."[163]This coconut was later kept on the president's desk, and is now in theJohn F. Kennedy Library.[164]

ThePhilippine Coast Guardusedunconventionalcoconut huskboomto clean up the oil slick in the2024 Manila Bay oil spill.[165]

Coir

Coir(the fiber from the husk of the coconut) is used inropes,mats,doormats,brushes,and sacks, ascaulkingfor boats, and as stuffing fiber formattresses.[166]It is used inhorticulturein potting compost, especially in orchid mix. The coir is used to make brooms in Cambodia.[162]

Leaves

The stiff midribs of coconut leaves are used for makingbroomsin India, Indonesia (sapu lidi), Malaysia, the Maldives, and the Philippines (walis tingting). The green of the leaves (lamina) is stripped away, leaving the veins (long, thin, woodlike strips) which are tied together to form a broom or brush. A long handle made from some other wood may be inserted into the base of the bundle and used as a two-handed broom.

The leaves also provide material forbasketsthat can draw well water and for roofingthatch;they can be woven into mats, cookingskewers,and kindlingarrowsas well. Leaves are also woven into small pouches that are filled with rice and cooked to makepusôandketupat.[167]

Dried coconut leaves can be burned to ash, which can be harvested forlime.In India, the woven coconut leaves are used to build weddingmarquees,especially in the states of Kerala,Karnataka,andTamil Nadu.

The leaves are used forthatchinghouses, or for decorating climbing frames andmeeting roomsin Cambodia, where the plant is known asdôô:ng.[162]

Timber

Coconut trunks are used for building small bridges and huts; they are preferred for their straightness, strength, and salt resistance. In Kerala, coconut trunks are used for house construction.Coconut timbercomes from the trunk, and is increasingly being used as an ecologically sound substitute for endangered hardwoods. It has applications in furniture and specialized construction, as notably demonstrated inManila'sCoconut Palace.

Hawaiians hollowed out the trunk to form drums, containers, or small canoes. The "branches" (leafpetioles) are strong and flexible enough to make aswitch.The use of coconut branches in corporal punishment was revived in the Gilbertese community on Choiseul in theSolomon Islandsin 2005.[168]

Roots

The roots are used as adye,amouthwash,and a folk medicine fordiarrheaanddysentery.[7]A frayed piece of root can also be used as atoothbrush.In Cambodia, the roots are used in traditional medicine as a treatment for dysentery.[162]

Other uses

The leftover fiber from coconut oil and coconut milk production, coconut meal, is used as livestock feed. The driedcalyxis used as fuel in wood-firedstoves.Coconut water is traditionally used as a growth supplement inplant tissue cultureandmicropropagation.[169]The smell of coconuts comes from the6-pentyloxan-2-onemolecule, known as δ-decalactone in the food and fragrance industries.[170]

Tool and shelter for animals

Researchers from theMelbourne Museumin Australia observed theoctopusspeciesAmphioctopus marginatususe tools,specifically coconut shells, for defense and shelter. The discovery of this behavior was observed inBaliandNorth Sulawesiin Indonesia between 1998 and 2008.[171][172][173]Amphioctopus marginatusis the firstinvertebrateknown to be able to use tools.[172][174]

A coconut can be hollowed out and used as a home for a rodent or a small bird. Halved, drained coconuts can also be hung up as bird feeders, and after the flesh has gone, can be filled with fat in winter to attracttits.

In culture

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2016) |

The coconut was a critical food item for the people ofPolynesia,and the Polynesians brought it with them as they spread to new islands.[175]

In theIlocos regionof the northern Philippines, theIlocano peoplefill two halved coconut shells withdiket(cooked sweet rice), and placeliningta nga itlog(halved boiled egg) on top of it. This ritual, known asniniyogan,is an offering made to the deceased and one's ancestors. This accompanies thepalagip(prayer to the dead).

A coconut (Sanskrit:narikela) is an essential element ofritualsinHindutradition.[176]Often it is decorated with bright metal foils and other symbols of auspiciousness. It is offered during worship to a Hindu god or goddess.Narali Purnimais celebrated on afull moonday which usually signifies the end ofmonsoonseason in India. The wordNaraliis derived fromnaralimplying "coconut" inMarathi.Fishermen give an offering of coconut to the sea to celebrate the beginning of a new fishing season.[177]Irrespective of their religious affiliations, fishermen of India often offer it to the rivers and seas in the hopes of having bountiful catches. Hindus often initiate the beginning of any new activity by breaking a coconut to ensure the blessings of the gods and successful completion of the activity. The Hindu goddess of well-being and wealth,Lakshmi,is often shown holding a coconut.[178]In the foothills of the temple town ofPalani,before going to worshipMuruganfor theGanesha,coconuts are broken at a place marked for the purpose. Every day, thousands of coconuts are broken, and some devotees break as many as 108 coconuts at a time as per the prayer.[citation needed]They are also used in Hindu weddings as a symbol of prosperity.[179]

The flowers are used sometimes in wedding ceremonies in Cambodia.[162]

TheZulu Social Aid and Pleasure ClubofNew Orleanstraditionally throws hand-decorated coconuts, one of the most valuableMardi Grassouvenirs, to parade revelers. The tradition began in the 1910s, and has continued since. In 1987, a "coconut law" was signed by GovernorEdwin Edwardsexempting from insurance liability any decorated coconut "handed" from a Zulu float.[180]

The coconut is also used as a target and prize in the traditional British fairground gamecoconut shy.The player buys some small balls which are then thrown as hard as possible at coconuts balanced on sticks. The aim is to knock a coconut off the stand and win it.[181]

It was the main food of adherents of the now discontinued Vietnamese religionĐạo Dừa.[182]

Myths and legends

Some South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Pacific Ocean cultures haveorigin mythsin which the coconut plays the main role. In theHainuwelemyth fromMaluku,a girl emerges from the blossom of a coconut tree.[183]InMaldivian folklore,one of the main myths of origin reflects the dependence of theMaldivianson the coconut tree.[184]In the story ofSina and the Eel,the origin of the coconut is related as the beautiful woman Sina burying an eel, which eventually became the first coconut.[185]

According to urban legend,more deaths are caused by falling coconuts than by sharksannually.[186]

Historical records

Literary evidence from theRamayanaandSri Lankan chroniclesindicates that the coconut was present in theIndian subcontinentbefore the 1st century BCE.[187]The earliest direct description is given byCosmas Indicopleustesin hisTopographia Christianawritten around 545, referred to as "the great nut of India".[188]Another early mention of the coconut dates back to the "One Thousand and One Nights"story ofSinbad the Sailorwherein he bought and sold a coconut during his fifth voyage.[189]

In March 1521, a description of the coconut was given byAntonio Pigafettawriting in Italian and using the words "cocho"/"cochi",as recorded in his journal after the first European crossing of the Pacific Ocean during theMagellancircumnavigationand meeting the inhabitants of what would become known as Guam and the Philippines. He explained how at Guam "they eat coconuts" ( "mangiano cochi") and that the natives there also" anoint the body and the hair with coconut andbeniseedoil "("ongieno el corpo et li capili co oleo de cocho et de giongioli").[190]

In politics

United States Vice PresidentKamala Harrissaid during a May 2023White Houseceremony "You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?",which became amemeamong her supporters duringher run for President in 2024.[191]

See also

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

- Central Plantation Crops Research Institute

- Coconut production in Kerala

- Coir Board of India

- List of coconut dishes

- List of dishes made using coconut milk

- Ravanahatha– a musical instrument sometimes made of coconuts

- Voanioala gerardii– forest coconut, the closest relative of the modern coconut

References

- ^ab"CocosL., Sp. Pl.: 1188 (1753) ".World Checklist of Selected Plant Families.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.2022. Archived fromthe originalon May 29, 2022.RetrievedMay 29,2022.

- ^Pearsall, J., ed. (1999). "Coconut".Concise Oxford Dictionary(10th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.ISBN0-19-860287-1.

- ^abNayar, N Madhavan (2017).The Coconut: Phylogeny, Origins, and Spread.Academic Press.pp. 10–21.ISBN978-0-12-809778-6.

- ^Michaels, Axel. (2006) [2004].Hinduism: past and present.Orient Longman.ISBN81-250-2776-9.OCLC398164072.

- ^abcdefLew, Christopher."Tracing the origin of the coconut (Cocos nuciferaL.) "(PDF).Prized Writing 2018–2019.University of California, Davis:143–157. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on June 23, 2021.RetrievedApril 22,2021.

- ^Pradeepkumar, T.; Sumajyothibhaskar, B.; Satheesan, K.N. (2008).Management of Horticultural Crops.Horticulture Science Series.Vol. 11, 2nd of 2 Parts.New India Publishing.pp. 539–587.ISBN978-81-89422-49-3.

- ^abGrimwood,p. 18.

- ^Sarian, Zac B. (August 18, 2010)."New coconut yields high".TheManila Bulletin.Archived fromthe originalon November 19, 2011.RetrievedApril 21,2011.

- ^Ravi, Rajesh (March 16, 2009)."Rise in coconut yield, farming area put India on top".TheFinancial Express.Archived fromthe originalon May 15, 2013.RetrievedApril 21,2011.

- ^"How Long Does It Take for a Coconut Tree to Get Coconuts?".Home Guides – SF Gate.August 20, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on November 13, 2014.

- ^abcLebrun, P.; Grivet, L.; Baudouin, L. (2013). "Use of RFLP markers to study the diversity of the coconut palm". In Oropeza, C.; Verdeil, J.K.; Ashburner, G.R.; Cardeña, R.; Santamaria, J.M. (eds.).Current Advances in Coconut Biotechnology.Springer Science & Business Media.pp. 83–85.ISBN978-94-015-9283-3.

- ^"Coconut Varieties".floridagardener.Archivedfrom the original on October 20, 2015.RetrievedMay 19,2016.

- ^ab"Coconut botany".Agritech Portal.Tamil Nadu Agricultural University.December 2014.RetrievedDecember 14,2017.

- ^abLédo, Ana da Silva; Passos, Edson Eduardo Melo; Fontes, Humberto Rolemberg; Ferreira, Joana Maria Santos; Talamini, Viviane; Vendrame, Wagner A.; Lédo, Ana da Silva; Passos, Edson Eduardo Melo; Fontes, Humberto Rolemberg; Ferreira, Joana Maria Santos; Talamini, Viviane; Vendrame, Wagner A. (2019)."Advances in Coconut palm propagation".Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura.41(2).doi:10.1590/0100-29452019159.ISSN0100-2945.

- ^Armstrong, W.P."Edible Palm Fruits".Wayne's Word: An On-Line Textbook of Natural History.Palomar College.Archived fromthe originalon September 2, 2018.RetrievedApril 20,2021.

- ^ab"Cocos nuciferaL. (Source: James A. Duke. 1983. Handbook of Energy Crops; unpublished) ".Purdue University,NewCROP – New Crop Resource. 1983.Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2015.RetrievedJune 4,2015.

- ^Sugimuma, Yukio; Murakami, Taka (1990)."Structure and Function of the Haustorim in Germinating Coconut Palm Seed"(PDF).JARQ.24:1–14.

- ^abcdefLebrun, P.; Seguin, M.; Grivet, L.; Baudouin, L. (1998). "Genetic diversity in coconut (Cocos nuciferaL.) revealed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) markers ".Euphytica.101:103–108.doi:10.1023/a:1018323721803.S2CID19445166.

- ^abcdShukla, A.; Mehrotra, R. C.; Guleria, J. S. (2012). "Cocos sahnii Kaul: ACocos nuciferaL.-like fruit from the Early Eocene rainforest of Rajasthan, western India ".Journal of Biosciences.37(4): 769–776.doi:10.1007/s12038-012-9233-3.PMID22922201.S2CID14229182.

- ^abcdeLutz, Diana (June 24, 2011)."Deep history of coconuts decoded".The Source.RetrievedJanuary 10,2019.

- ^abPaull, Robert E.; Ketsa, Saichol (March 2015).Coconut: Postharvest Quality-Maintenance Guidelines(PDF).College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources,University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

- ^abCoconut: Postharvest Care and Market Preparation(PDF).Technical Bulletin No. 27.Ministry of Fisheries, Crops and Livestock,New Guyana Marketing Corporation,National Agricultural Research Institute.May 2004.

- ^abThampan, P.K. (1981).Handbook on Coconut Palm.Oxford &IBH Publishing Co.

- ^abElevitch, C.R., ed. (April 2006). "Cocos nucifera(coconut), version 2.1 ".Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry(PDF).Hōlualoa,Hawai‘i:Permanent Agriculture Resources.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 20, 2013.RetrievedDecember 22,2016.

- ^Willmer, Pat (July 25, 2011).Pollination and Floral Ecology.Princeton University Press. p. 57.ISBN978-0-691-12861-0.

- ^abcSrivastava, Rashmi; Srivastava, Gaurav (2014)."Fossil fruit ofCocosL. (Arecaceae) from Maastrichtian-Danian sediments of central India and its phytogeographical significance ".Acta Palaeobotanica.54(1): 67–75.doi:10.2478/acpa-2014-0003.

- ^abcdefNayar, N. Madhavan (2016).The Coconut: Phylogeny, Origins, and Spread.Academic Press.pp. 51–66.ISBN978-0-12-809779-3.

- ^abConran, John G.; Bannister, Jennifer M.; Lee, Daphne E.; Carpenter, Raymond J.; Kennedy, Elizabeth M.; Reichgelt, Tammo; Fordyce, R. Ewan (2015)."An update of monocot macrofossil data from New Zealand and Australia".Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society.178(3). TheLinnean Society:394–420.doi:10.1111/boj.12284.

- ^Endt, D.; Hayward, B. (1997). "Modern relatives of New Zealand's fossil coconuts from high altitude South America".New Zealand Geological Society Newsletter.113:67–70.

- ^Hayward, Bruce (2012). "Fossil Oligocene coconut from Northland".Geocene.7(13).

- ^Singh, Hukam; Shukla, Anumeha; Mehrotra, R.C. (2016)."A Fossil Coconut Fruit from the Early Eocene of Gujarat".Journal of Geological Society of India.87(3): 268–270.Bibcode:2016JGSI...87..268S.doi:10.1007/s12594-016-0394-9.S2CID131318482.RetrievedJanuary 10,2019.

- ^abHarries, Hugh C.; Clement, Charles R. (2014)."Long-distance dispersal of the coconut palm by migration within the coral atoll ecosystem".Annals of Botany.113(4): 565–570.doi:10.1093/aob/mct293.PMC3936586.PMID24368197.

- ^Dalgado, Sebastião (1919).Glossário luso-asiático.Vol. 1. Coimbra, Imprensa da Universidade. p. 291.

- ^"coco".Online Etymology Dictionary.RetrievedMay 3,2020.

- ^"coconut".Online Etymology Dictionary.RetrievedMay 3,2020.

- ^abLosada, Fernando Díez (2004).La tribuna del idioma(in Spanish). Editorial Tecnologica de CR. p. 481.ISBN978-9977-66-161-2.

- ^Figueiredo, Cândido (1940).Pequeno Dicionário da Lingua Portuguesa(in Portuguese). Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand.

- ^abElzebroek, A. T. G. (2008).Guide to Cultivated Plants.CABI. pp. 186–192.ISBN978-1-84593-356-2.

- ^Grimwood,p. 1.

- ^Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940)."κόκκος".A Greek-English Lexicon.Perseus Digital Library.

- ^Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879)."cŏquus".A Latin Dictionary.Perseus Digital Library.

- ^Furtado, C. X. (1964)."On The Etymology Of The Word Cocos"(PDF).Principes.8:107-112.RetrievedNovember 5,2022– via International Palm Society.

- ^"National Flower – Nelumbo nucifera"(PDF).ENVIS Resource Partner on Biodiversity.RetrievedFebruary 19,2021.

- ^abcVollmann, Johann; Rajcan, Istvan (September 18, 2009).Oil Crops.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 370–372.ISBN978-0-387-77594-4.

- ^Chambers, Geoff (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians".eLS.John Wiley & Sons, Inc.doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2.ISBN978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^Blench, Roger (2009)."Remapping the Austronesian expansion"(PDF).In Evans, Bethwyn (ed.).Discovering History Through Language: Papers in Honour of Malcolm Ross.Pacific Linguistics.ISBN978-0-85883-605-1.