Terminology of the Low Countries

TheLow Countriescomprise the coastalRhine–Meuse–Scheldt deltaregion inWestern Europe,whose definition usually includes the modern countries ofLuxembourg,Belgiumand theNetherlands.[1][2]Both Belgium and the Netherlands derived their names from earlier names for the region, due tonethermeaning "low" andBelgicabeing theLatinized namefor all the Low Countries,[3]anomenclaturethat became obsolete afterBelgium's secession in 1830.

The Low Countries—and the Netherlands and Belgium—had in their history exceptionally many and widely varying names, resulting in equally varying names in different languages. There is diversity even within languages: the use of one word for the country and another for the adjective form is common. This holds for English, whereDutchis the adjective form for the country "the Netherlands". Moreover, many languages have the same word for both the country of the Netherlands and the region of the Low Countries, e.g., French (les Pays-Bas) and Spanish (los Países Bajos). The complicated nomenclature is a source of confusion for outsiders, and is due to the long history of the language, the culture and the frequent change of economic and military power within the Low Countries over the past 2,000 years.

History

[edit]The historic Low Countries made up much ofFrisia,home to theFrisii,and theRomanprovinces ofGallia BelgicaandGermania Inferior,home to theBelgaeandGermanic peopleslike theBatavi.Throughout the centuries, the names of these ancestors have been in use as a reference to the Low Countries, in an attempt to define a collective identity. In the 4th and 5th centuries aFrankishconfederation of Germanic tribes significantly made a lasting change by entering the Roman provinces and starting to build theCarolingian Empire,of which the Low Countries formed a core part.

By the 8th century, most of the Franks had exchanged their GermanicFrankish languagefor the Latin-derivedRomancesofGaul.The Franks that stayed in the Low Countries had kept their original language, i.e.,Old Dutch,also known as "Old Low Franconian" among linguists. At the time the language was spoken, it was known as *þiudisk,meaning "of the people" —as opposed to the Latin language "of theclergy"—which is the source of the English wordDutch.Now an international exception, it used to have in the Dutch language itself acognatewith the same meaning, i.e.,Diets(c)orDuuts(c).

The designation "low" to refer to the region has also been in use many times. First by the Romans, who called it Germania "Inferior". After theFrankish empirewas divided several times, most of it became the Duchy ofLower Lorrainein the 10th century, where the Low Countries politically have their origin.[4][5]Lower Lorraine disintegrated into a number of duchies, counties and bishoprics. Some of these became so powerful, that their names were used as apars pro totofor the Low Countries, i.e.,Flanders,Hollandand to a lesser extentBrabant.Burgundian,and laterHabsburg rulers[6][7]added one by one the Low Countries' polities in a single territory, and it was at theirfrancophonecourts that the termles pays de par deçàarose, that would develop inLes Pays-Basor in English "Low Countries" or "Netherlands".

Theodiscusand derivatives

[edit]

Dutch,DietsandDuyts

[edit]English is one of the only languages to use the adjectiveDutchfor the language of the Netherlands and Flanders. The word is derived fromProto-Germanic*þiudiskaz.The stem of this word,*þeudō,meant "people" in Proto-Germanic, and*-iskazwas an adjective-forming suffix, of which-ishis theModern Englishform.[8]Theodiscuswas itsLatinisedform[9]and used as anadjectivereferring to theGermanicvernacularsof theEarly Middle Ages.In this sense, it meant "the language of the common people", that is, the native Germanic language. The term was used as opposed toLatin,thenon-native language of writing and theCatholic Church.[10]It was first recorded in 786, when theBishop of Ostiawrites toPope Adrian Iabout asynodtaking place inCorbridge,England,where the decisions are being written down "tam Latine quam theodisce" meaning "in Latin as well as Germanic".[11][12][13]So in this sensetheodiscusreferred to the Germanic language spoken in Great Britain, which was later replaced by the nameEnglisc.[14]

By the late 14th century,þēodischad given rise toMiddle Englishducheand its variants, which were used as a blanket term for all the non-ScandinavianGermanic languagesspoken on the European mainland. Historical linguists have noted that the medieval "Duche" itself most likely shows an externalMiddle Dutchinfluence, in that it shows avoiced alveolar stoprather than the expectedvoiced dental fricative.This would be a logical result of theMedieval English wool trade,which brought the English in close linguistic contact with the cloth merchants living in the Dutch-speaking cities ofBrugesandGhent,who at the time, referred to their language asdietsc.[15]

Its exact meaning is dependent on context, but tends to be vague regardless.[16]When concerning language, the wordduchecould be used as a hypernym for several languages (The North est Contrey which lond spekyn all maner Duche tonge – The North [of Europe] is an area, in which all lands speak all manner of "Dutch" languages) but it could also suggest singular use (In Duche a rudder is a knyght – In "Dutch" a rudder [cf.Dutch:ridder] is a knight) in which case linguistic and/or geographic pointers need to be used to determine or approximate what the author would have meant in modern terms, which can be difficult.[17]For example, in his poemConstantyne,the English chroniclerJohn Hardyng(1378–1465) specifically mentions the inhabitants of three Dutch-speaking fiefdoms (Flanders, Guelders and Brabant) as travel companions, but also lists the far more general "Dutchemēne" and "Almains", the latter term having an almost equally broad meaning, though being more restricted in its geographical use; usually referring to people and locaties within modernGermany,SwitzerlandandAustria:

He went to Roome with greate power of Britons strong, |

He went to Rome with a large number of Britons, |

| —Excerpt from "Constantyne",John Hardyng | —J. Rivington, The Chronicle of Iohn Hardyng |

By early 17th century, general use of the word Dutch had become exceedingly rare inGreat Britainand it became anexonymspecifically tied tothe modern Dutch,i.e. theDutch-speakinginhabitants of theLow Countries.Many factors facilitated this, including close geographic proximity, trade and military conflicts, for instance theAnglo-Dutch Wars.[20][21]Due to the latter, "Dutch" also became a pejorative label pinned by English speakers on almost anything they regard as inferior, irregular, or contrary to their own practice. Examples include "Dutch treat" (each person paying for himself), "Dutch courage" (boldness inspired by alcohol), "Dutch wife" (a type ofsex doll) and "Double Dutch" (gibberish, nonsense) among others.[22]

In theUnited States,the word "Dutch" remained somewhat ambiguous until the start of the 19th century. Generally, it referred to the Dutch, their language or theDutch Republic,but it was also used as an informal monniker (for example in the works ofJames Fenimore CooperandWashington Irving) for people who would today be considered Germans or German-speaking, most notably thePennsylvania Dutch.This lingering ambiguity was most likely caused by close proximity to German-speaking immigrants, who referred to themselves or (in the case of the Pennsylvania Dutch) their language as "Deutsch" or "Deitsch", rather than archaic use of the term "Dutch"[23][24][25][26][27][28]

In the Dutch language itself,Old Dutch*thiudiskevolved into a southern variantduutscand a western variantdietscinMiddle Dutch,which were both known asduytschin Early Modern Dutch. In the earliest sources, its primary use was to differentiate between Germanic and the Romance dialects, as expressed by the Middle Dutch poetJan van Boendale,who wrote:[20][29]

Want tkerstenheit es gedeelt in tween, |

|

| —Excerpt from "Brabantsche Yeesten",by Jan van Boendale (1318)[30] |

During theHigh Middle Ages"Dietsc/Duutsc" was increasingly used as an umbrella term for the specific Germanic dialects spoken in theLow Countries,its meaning being largely implicitly provided by the regional orientation of medieval Dutch society: apart from the higher echelons of the clergy and nobility, mobility was largely static and hence while "Dutch" could by extension also be used in its earlier sense, referring to what to today would be called Germanic dialects as opposed toRomance dialects,in many cases it was understood or meant to refer to the language now known as Dutch.[20][21][31]Apart from the sparsely populated eastern borderlands, there was little to no contact with contemporary speakers of German dialects, let alone a concept of the existence of German as language in its modern sense among the Dutch. Because medieval trade focused on travel by water and with the most heavily populated areas adjacent to Northwestern France, the average 15th century Dutchman stood a far greater chance of hearing French or English than a dialect of the German interior, despite its relative geographical closeness.[32]Medieval Dutch authors had a vague, generalized sense of common linguistic roots between their language and various German dialects, but no concept of speaking the same language existed. Instead they saw their linguistic surroundings mostly in terms of small scale regiolects.[33]

In the 19th century, the term "Diets" was revived by Dutch linguists and historians as a poetic name forMiddle Dutchandits literature.[34]

Nederduits

[edit]In the second half of the 16th century theneologism"Nederduytsch" (literally: Nether-Dutch, Low-Dutch) appeared in print, in a way combining the earlier "Duytsch" and "Nederlandsch" into one compound. The term was preferred by many leading contemporary grammarians such as Balthazar Huydecoper, Arnold Moonen and Jan ten Kate because it provided a continuity withMiddle Dutch( "Duytsch" being the evolution of medieval "Dietsc" ), was at the time considered the proper translation of the Roman Province ofGermania Inferior(which not only encompassed much of the contemporary Dutch-speaking area / Netherlands, but also added classical prestige to the name) and amplified the dichotomy between Early Modern Dutch and the "Dutch" (German) dialects spoken around theMiddleandUpper Rhinewhich had begun to be calledoverlantschofhoogduytsch(literally: Overlandish, High- "Dutch" ) by Dutch merchants sailing upriver.[35]Though "Duytsch" forms part of the compound in both Nederduytsch and Hoogduytsch, this should not be taken to imply that the Dutch saw their language as being especially closely related to the German dialects spoken in Southerwestern Germany. On the contrary, the term "Hoogduytsch" specifically came into being as a special category because Dutch travelers visiting these parts found it hard to understand the local vernacular: in a letter dated to 1487 a Flemish merchant from Bruges instructs his agent to conduct trade transactions inMainzin French, rather than the local tongue to avoid any misunderstandings.[35]In 1571 use of "Nederduytsch" greatly increased because theSynod of Emdenchose the name "Nederduytsch Hervormde Kerk" as the official designation of theDutch Reformed Church.The synods choice of "Nederduytsch" over the more dominant "Nederlandsch", was inspired by the phonological similarities between "neder-" and "nederig" (the latter meaning "humble" ) and the fact that it did not contain a worldly element ( "land" ), whereas "Nederlandsch" did.[35]

As the Dutch increasingly referred to their own language as "Nederlandsch" or "Nederduytsch", the term "Duytsch" became more ambiguous. Dutchhumanists,started to use "Duytsch" in a sense which would today be called "Germanic", for example in a dialogue recorded in the influential Dutch grammar book "Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst", published in 1584:

R. ghy zeyde flux dat de Duytsche taal by haar zelven bestaat/ ick heb my wel laten segghen, |

R: You've just said that the Dutch language exists in its own right, |

| —Excerpt from "Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst", byHendrik Laurenszoon Spiegel(1584)[36][30] |

In the Dutch language itself,Diets(c)(laterDuyts) was used as one of severalExonym and endonyms.As the Dutch increasingly referred to their own language as "Nederlandsch" or "Nederduytsch", the term "Duytsch" became more ambiguous. Dutchhumanists,started to use "Duytsch" in a sense which would today be called "Germanic". Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the nomenclature gradually became more fixed, with "Nederlandsch" and "Nederduytsch" becoming the preferred terms for Dutch and with "Hooghduytsch" referring to the language today called German. Initially the word "Duytsch" itself remained vague in exact meaning, but after the 1650s a trend emerges in which "Duytsch" is taken as the shorthand for "Hooghduytsch". This process was probably accelerated by the large number of Germans employed as agricultural day laborers and mercenary soldiers in theDutch Republicand the ever increasing popularity of "Nederlandsch" and "Nederduytsch" over "Duytsch", the use of which had already been in decline for over a century, thereby acquiring its current meaning (German) in Dutch.[37][29][38]

In the late 19th century "Nederduits" was reintroduced to Dutch through the German language, where prominent linguists, such as theBrothers GrimmandGeorg Wenker,in the nascent field of German and Germanic studies used the term to refer to Germanic dialects which had not taken part in theHigh German consonant shift.Initially this group consisted of Dutch,English,Low GermanandFrisian,but in modern scholarship only refers toLow German-varieties. Hence in contemporary Dutch, "Nederduits" is used to describe Low German varieties, specifically those spoken in Northern Germany as the varieties spoken in the eastern Netherlands, while related, are referred to as "Nedersaksisch".[39]

Names from low-lying geographical features

[edit]

Place names with "low(er)" orneder,lage,nieder,nether,nedre,basandinferiorare used everywhere in Europe. They are often used in contrast with an upstream or higher area whose name contains words such as "upper",boven,oben,supérieureandhaut.Both downstream at theRhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta,and low at the plain near theNorth Seaapply to theLow Countries.[clarification needed]The related geographical location of the "upper" ground changed over time tremendously, and rendered over time several names for the area now known as the Low Countries:

- Germania inferior:Roman province established in AD 89 (parts of Belgium and the Netherlands), downstream fromGermania Superior(southern Germany). In the 16th century the term was used again, though without this contrastive counterpart.

- Lower Lorraine:10th century duchy (covered much of the Low Countries), downstream fromUpper Lorraine(northern France)

- Niderlant: Since the 12th century,Niderlant( "Low land" ) was mentioned in theNibelungenliedas the region between theMeuseand the lowerRhine.In this context the higher ground began approximately at upstreamCologne.[clarification needed]

- Les pays de par deçà:used by 15th century Burgundian rulers who resided in the Low Countries, meaning "the lands over here". On the other hand,Les pays de par delàor "the lands over there" was used for their original homelandBurgundy(central France).[40]

- Pays d'embas:used by 16th century Habsburg rulerMary, Queen of Hungary,meaning "land down here", used as opposed to her other possessions on higher grounds in Europe (Austria and Hungary). Possibly developed from "Les pays de par deçà".[41]

Netherlands

[edit]

Apart from its topographic usage for the then multi-government area of the Low Countries, the 15th century saw the first attested use ofNederlandschas a term for the Dutch language, by extension hinting at a commonethnonymfor people living in different fiefdoms.[42][43]This was used alongside the long-standingDuytsch(the Early Modern spelling of the earlierDietscorDuutsc). The most common Dutch term for the Dutch language remainedNederduytschorNederduitschuntil it was gradually superseded byNederlandschin the early 1900s, the latter becoming the sole name for the language by 1945. Earlier, from the mid-16th century on, theEighty Years' War(1568–1648) had divided the Low Countries into the northernDutch Republic(Latin:Belgica Foederata) and the southernSpanish Netherlands(Latin:Belgica Regia), introducing a distinction, i.e. Northern vs. Southern Netherlands; the latter evolved into the present-day Belgium after a brief unification in the early 19th century.

The English adjective "Netherlandish", meaning "from the Low Countries", is derived directly from the Dutch adjectiveNederlandsorNederlandsch,and the French and German equivalents. It is now rare in general use, but remains used in history, especially in reference to art or music produced anywhere in the Low Countries during the 15th and early 16th centuries. "Early Netherlandish painting",has replaced" Flemish Primitives ", despite the equivalents remaining current in French, Dutch and other languages; the latter is now only seen in poorly-translated material from a language that uses it. In English the pejorative sense of" primitive "makes the term impossible to use in such a context.

In music theFranco-Flemish Schoolis also known as the Netherlandish School. Later art and artists from the southernCatholicprovinces of the Low Countries are usually calledFlemishand those from the northernProtestantprovinces Dutch, but art historians sometimes use "Netherlandish art" forart of the Low Countriesproduced before 1830, i.e., until the secession of Belgium from the Netherlands to distinguish the period from what came after.

Apart from this largely intellectual use, the term "Netherlandish" as adjective is not commonly used in English, unlike its Dutch equivalent. Many languages have acognateorcalquederived from the Dutch adjectiveNederlands:

|

|

Toponyms

[edit]- Burgundian Netherlands:Low Countries provinces held by theHouse of Valois-Burgundy(1384–1482)

- Habsburg Netherlands:Low Countries provinces held by theHouse of Habsburgand later theSpanish Empire(1482–1581)

- Seven United Netherlands:Dutch Republic (1581–1795)

- Southern Netherlands:comprising present Belgium, Luxembourg and parts of northern France (1579–1794)

- Spanish Netherlands:comprising present Belgium, Luxembourg and parts of northern France (1579–1713)

- Austrian Netherlands:comprising present Belgium, Luxembourg and parts of northern France under Habsburg rule (after 1713)

- Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands:short-lived precursor of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1813–1815)

- United Kingdom of the Netherlands:unification of the Northern Netherlands and the Southern Netherlands (Belgium and Luxembourg) (1815–1830)

- Kingdom of the Netherlands:kingdom with the Netherlands, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten as constituent countries

- Netherlands:European part of the kingdom of the Netherlands

- New Netherland:Former Dutch colony established in 1625 centred onNew Amsterdam(the modernNew York City)

Low Countries

[edit]TheLow Countries(Dutch:Lage Landen) refers to the historical regionde Nederlanden:those principalities located on and near the mostly low-lying land around theRhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta.That region corresponds to all of the Netherlands,BelgiumandLuxembourg,forming theBenelux.The name "Benelux" is formed from joining the first two or three letters of each country's nameBelgium,Netherlands andLuxembourg. It was first used to namethe customs agreement that initiated the union(signed in 1944) and is now used more generally to refer to the geopolitical and economical grouping of the three countries, while "Low Countries" is used in a more cultural or historical context.

In many languages the nomenclature "Low Countries" can both refer to the cultural and historical region comprising present-day Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, and to "the Netherlands" alone, e.g.,Les Pays-Basin French,Los Países Bajosin Spanish andi Paesi Bassiin Italian. Several other languages have literally translated "Low Countries" into their own language to refer to the Dutch language:

- Croatian:Nizozemski

- Czech:Nizozemština

- Irish:Ísiltíris

- Southern Min:Vùng đất thấp ngữ/Vùng đất thấp ngữ(Kē-tē-gú)

- Serbian:низоземски (nizozemski)

- Slovene:nizozemščina

- Welsh:Iseldireg

Names from local polities

[edit]Flanders (pars pro toto)

[edit]

Flemish(Dutch:Vlaams) is derived from the name of theCounty of Flanders(Dutch:Graafschap Vlaanderen), in the early Middle Ages the most influential county in theLow Countries,and the residence of theBurgundian dukes.Due to its cultural importance, "Flemish" became in certain languages apars pro totofor the Low Countries and the Dutch language. This was certainly the case in France, since the Flemish are the first Dutch speaking people for them to encounter. In French-Dutch dictionaries of the 16th century, "Dutch" is almost always translated asFlameng.[45]

A calque ofVlaamsas a reference to the language of the Low Countries was also in use in Spain. In the 16th century, when Spain inherited theHabsburg Netherlands,the whole area of the Low Countries was indicated asFlandes,and the inhabitants ofFlandeswere calledFlamencos.For example, theEighty Years' Warbetween the rebelliousDutch Republicand the Spanish Empire was calledLas guerras de Flandes[46]and the Spanish army that was based in the Low Countries was named theArmy of Flanders(Spanish:Ejército de Flandes).

The English adjective "Flemish" (first attested asflemmysshe,c. 1325;[47]cf.Flæming,c. 1150),[48]was probably borrowed fromOld Frisian.[49]The nameVlaanderenwas probably formed from a stemflām-,meaning "flooded area" (cf.Norwegianflaum‘flood’,Englishdialectalfleam‘millstream; trench or gully in a meadow that drains it’), with a suffix-ðr-attached.[50]TheOld Dutchform isflāmisk,which becomesvlamesc,vlaemschinMiddle DutchandVlaamsinModern Dutch.[51]Flemish is now exclusively used to describe the majority of Dutch dialects found inFlanders,and as a reference to that region. Calques ofVlaamsin other languages:

|

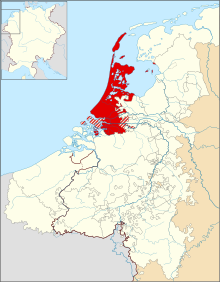

Holland (pars pro toto)

[edit]In many languages including English, (acalqueof) "Holland" is a common name for theNetherlandsas a whole. Even the Dutch use this sometimes, although this may be resented outside the two modern provinces that make up historical Holland. Strictly speaking,Hollandis only the central-western region of the country comprising two of the twelve provinces. They areNorth HollandandSouth Holland.Holland has, particularly for outsiders, long become apars pro totoname for the whole nation, similar to the use ofRussiafor the (former)Soviet Union,orEnglandfor theUnited Kingdom.

The use is sometimes discouraged. For example, the "Holland" entry in thestyle guideofThe GuardianandThe Observernewspapers states: "Do not use when you mean the Netherlands (of which it is a region), with the exception of theDutch football team,which is conventionally known as Holland ".[52]

In 2019, the Dutch government announced that it would only communicate and advertise under its real name "the Netherlands" in the future, and stop describing itself as Holland. They stated: “It has been agreed that the Netherlands, the official name of our country, should preferably be used.”[53][54]From 2019 onwards, thenation's football teamwill solely be called the Netherlands in any official setting.[53]Nonetheless, the name "Holland" is still widely used for the Netherlands national football team.[55][56]

From the 17th century onwards, theCounty of Hollandwas the most powerful region in the current Netherlands. Thecounts of Hollandwere also counts ofHainaut,FrieslandandZeelandfrom the 13th to the 15th centuries. Holland remained most powerful during the period of theDutch Republic,dominating foreign trade, and hence most of the Dutch traders encountered by foreigners were from Holland, which explains why the Netherlands is often called Holland overseas.[57]

After the demise of the Dutch Republic under Napoleon, that country became known as theKingdom of Holland(1806–1810). This is the only time in history that "Holland" became an official designation of the entire Dutch territory. Around the same time, the former countship of Holland was dissolved and split up into two provinces, later known asNorth HollandandSouth Holland,because one Holland province by itself was considered too dominant in area, population and wealth compared to the other provinces. Today the two provinces making up Holland, including the cities ofAmsterdam,The HagueandRotterdam,remain politically, economically and demographically dominant – 37% of theDutch populationlive there. In most other Dutch provinces, particularly in the south includingFlanders(Belgium), the wordHollanderis commonly used in either colloquial orpejorativesense to refer to the perceived superiority or supposed arrogance of people from theRandstad– the mainconurbationof Holland proper and of the Netherlands.

In 2009, members of theFirst Chamberdrew attention to the fact that in Dutch passports, for some EU-languages a translation meaning "Kingdom of Holland" was used, as opposed to "Kingdom of the Netherlands". As replacements for theEstonianHollandi Kuningriik,HungarianHolland Királyság,RomanianRegatul OlandeiandSlovakHolandské kráľovstvo,the parliamentarians proposedMadalmaade Kuningriik,Németalföldi Királyság,Regatul Țărilor de JosandNizozemské Kráľovstvo,respectively. Their reasoning was that "if in addition to Holland a recognisable translation of the Netherlands does exist in a foreign language, it should be regarded as the best translation" and that "the Kingdom of the Netherlands has a right to use the translation it thinks best, certainly on official documents".[58]Although the government initially refused to change the text except for the Estonian, recent Dutch passports feature the translation proposed by the First Chamber members. Calques derived fromHollandto refer to the Dutch language in other languages:

|

|

Toponyms:

- County of Holland:former county in the Netherlands, dissolved in the provinces North and South Holland

- South Holland(Zuid-Holland): province in the Netherlands

- North Holland(Noord-Holland): province in the Netherlands

- Holland:region, former county in the Netherlands consisting of the provinces Noord- en Zuid-Holland

- Kingdom of Holland:puppet state set up byNapoleonwho took the name of the leading province for the whole country (1806–1810)

- New Holland(Nova Hollandia):historical name for mainlandAustralia(1644–1824)

- New Holland:Dutch colony inBrazil(1630–1654)

- Holland, Michigan

- Hollandia (city):between 1910 and 1949 the capital of a district of the same name inWest New Guinea,nowJayapura

Brabant (pars pro toto)

[edit]

As the Low Country's prime duchy, with the only and oldest scientific centre (theUniversity of Leuven),Brabanthas served as a pars pro toto for the whole of the Low Countries, for example in the writings ofDesiderius Erasmusin the early 16th century.[59]

Perhaps of influence for this pars pro toto usage is the Brabantian holding of the ducal title ofLower Lorraine.In 1190, after the death ofGodfrey III,Henry Ibecame Duke of Lower Lorraine, where the Low Countries have their political origin. By that time the title had lost most of its territorial authority. According to protocol, all his successors were thereafter called Dukes of Brabant and Lower Lorraine (often called Duke of Lothier).

Brabant symbolism served again a role as national symbols during the formation of Belgium. Thenational anthemof Belgium is called theBrabançonne(English: "the Brabantian" ), and the Belgium flag has taken its colors from the Brabant coat of arms: black, yellow and red. This was influenced by theBrabant Revolution(French:Révolution brabançonne,Dutch:Brabantse Omwenteling), sometimes referred to as the "Belgian Revolution of 1789–90" in older writing, that was an armedinsurrectionthat occurred in theAustrian Netherlands(modern-dayBelgium) between October 1789 and December 1790. The revolution led to the brief overthrow ofHabsburg ruleand the proclamation of a short-lived polity, theUnited Belgian States.Some historians have seen it as a key moment inthe formation of a Belgian nation-state,and an influence on theBelgian Revolutionof 1830.

Seventeen and Seven Provinces

[edit]Holland, Flanders and 15 other counties, duchies and bishoprics in the Low Countries were united as theSeventeen Provincesin apersonal unionduring the 16th century, covered by thePragmatic Sanction of 1549ofHoly Roman EmperorCharles V,which freed the provinces from their archaic feudal obligations.

In 1566,Philip II of Spain,heir of Charles V, sent an army of Spanish mercenaries to suppress political upheavals to the Seventeen Provinces. A number of southern provinces (Hainaut,Artois,Walloon Flanders,Namur,LuxembourgandLimburg) united in theUnion of Arras(1579), and begun negotiations for a peace treaty with Spain. In response, nine northern provinces united in theUnion of Utrecht(1579) against Spain. After theFlandersand theBrabantwhere reconquered by Spain, the remaining seven provinces (Frisia,Gelre,Holland,Overijssel,Groningen,UtrechtandZeeland) signed 2 years later the declaration of independence of theSeven United Provinces.Since then, several ships of theRoyal Netherlands Navyhave bared that name.

Names from tribes of the pre-Migration Period

[edit]Belgae

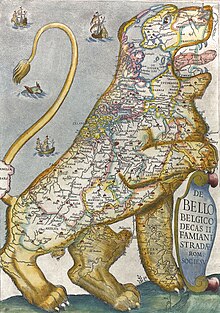

[edit]The nomenclatureBelgicais harking back to the ancient local tribe of theBelgaeand the Roman province named after that tribeGallia Belgica.Although a derivation of that name is now reserved for the Kingdom ofBelgium,from the 15th to the 17th century the name was the usual Latin translation to refer to the entireLow Countries,which was on maps sometimes heroically visualised as theLeo Belgicus.[60] Other use:

- Lingua Belgica: Latinized name for the Dutch language in 16th century dictionaries, popular under the influence ofHumanism[61]

- Belgica Foederata:literally "United Belgium", Latinized name for the Dutch Republic (also known as United Netherlands, Northern Netherlands or United Provinces), after the northern part of the Low Countries declared its independence from theSpanish Empire

- Belgica Regia:literally "King's Belgium", Latinized name for the Southern Netherlands, remained faithful to the Spanish king

- Nova Belgica:Latined name for the former colonyNew Netherland

- Fort Belgica:fort built by the Dutch in the IndonesianBanda Islandsin the 17th century.

- United Belgian States:also known as "United Netherlandish States" (Dutch:Verenigde Nederlandse Staten) or "United States of Belgium", short-lived Belgian precursor state established after theBrabant Revolutionagainst theHabsburg(1790)

- Belgium:state in Europe

Batavi

[edit]

Throughout the centuries the Dutch attempted to define their collective identity by looking at their ancestors, the Batavi. As claimed by the Roman historianTacitus,the Batavi were a brave Germanic tribe living in the Netherlands, probably in theBetuweregion. In Dutch, the adjectiveBataafs( "Batavian" ) was used from the 15th to the 18th century, meaning "of, or relating to the Netherlands" (but not the southern Netherlands).

Other use:

- Lingua Batava or Batavicus: in use as Latin names for the Dutch language[61]

- Batavisme: in French an expression copied from the Dutch language[62]

- Batave: in French a person from the Netherlands[63]

- Batavian Legion:a unit of Dutch volunteers under French command, created and dissolved in 1793

- Batavian Revolution:political, social and cultural turmoil in the Netherlands (end 18th century)

- Batavian Republic(Dutch:Bataafse Republiek;French:République Batave), Dutchclient stateof France (1795–1806)

- Batavia, Dutch East Indies:capital city of theDutch East Indies,corresponds to the present-day city ofJakarta

Frisii

[edit]Names from confederations of Germanic tribes

[edit]Franconian

[edit]Frankishwas theWest Germanic languagespoken by theFranksbetween the 4th and 8th century. Between the 5th and 9th centuries, the languages spoken by theSalian Franksin Belgium and the Netherlands evolved intoOld Low Franconian(Dutch:Oudnederfrankisch), which formed the beginning of a separate Dutch language and is synonymous withOld Dutch.Compare the synonymous usage, in a linguistic context, ofOld EnglishversusAnglo-Saxon.

Frisian

[edit]Frisiiwere an ancient tribe who lived in the coastal area of the Netherlands in Roman times. After theMigration PeriodAnglo-Saxons,coming from the east, settled the region.Franksin the south, who were familiar with Roman texts, called the coastal regionFrisia,and hence its inhabitantsFrisians,even though not all of the inhabitants had Frisian ancestry.[64][65][66]After aFrisian Kingdomemerged in the mid-7th century in the Netherlands, with its center of power the city ofUtrecht,[67]the Franks conquered the Frisians and converted them to Christianity. From that time on a colony of Frisians was living in Rome and thus the old name for the people from theLow Countrieswho came to Rome has remained in use in the national church of the Netherlands in Rome, which is called theFrisian church(Dutch:Friezenkerk;Italian:chiesa nazionale dei Frisoni). In 1989, this church was granted to the Dutch community in Rome.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Low Countries".Encyclopædia Britannica.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2015.Retrieved26 January2014.

- ^"Low Countries - definition of Low Countries by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia".Farlex, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2019.Retrieved26 January2014.

- ^derived from the ancientBelgaeconfederation of tribes.

- ^"Franks".Columbia Encyclopedia.Columbia University Press.2013.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2016.Retrieved1 February2014.

- ^"Lotharingia / Lorraine ( Lothringen )".5 September 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2019.Retrieved1 February2014.

- ^"1. De landen van herwaarts over".Vre.leidenuniv.nl. Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2016.Retrieved1 January2014.

- ^Alastair Duke."The Elusive Netherlands. The question of national identity in the Early Modern Low Countries on the Eve of the Revolt".Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2013.Retrieved1 January2014.

- ^Mallory, J. P.;Adams, D. Q.(2006),The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World,USA: Oxford University Press,ISBN0-19-929668-5,archivedfrom the original on 31 August 2021,retrieved6 April2016,p. 269.

- ^W. Haubrichs, "Theodiscus,Deutsch und Germanisch - drei Ethnonyme, drei Forschungsbegriffe. Zur Frage der Instrumentalisierung und Wertbesetzung deutscher Sprach- und Volksbezeichnungen. "In: H. Beck et al.,Zur Geschichte der Gleichung "germanisch-deutsch"(2004), 199–228

- ^Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary,2nd revised edn., s.v. "Dutch" (Random House Reference, 2005).

- ^M. Philippa e.a. (2003–2009) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands [diets]

- ^Strabo, Walafridus (1996).Walahfrid Strabo's Libellus de Exordiis Et Incrementis Quarundam in... a translation by Alice L. Harting-Correa.BRILL.ISBN9004096698.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023.Retrieved6 April2016.

- ^Cornelis Dekker: The Origins of Old Germanic Studies in the Low Countries[1]Archived24 March 2023 at theWayback Machine

- ^Roland Willemyns (2013).Dutch: Biography of a Language.Oxford University Press. p. 5.ISBN9780199323661.Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2023.Retrieved3 October2020.

- ^P.A.F. van Veen en N. van der Sijs (1997), Etymologisch woordenboek: de herkomst van onze woorden, 2e druk, Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht/Antwerpen

- ^H. Kurath: Middle English Dictionary, part 14, University of Michigan Press, 1952, 1346.

- ^H. Kurath: Middle English Dictionary, part 14, University of Michigan Press, 1952, 1345.

- ^F.C. and J. Rivington, T. Payne, Wilkie and Robinson: The Chronicle of Iohn Hardyng, 1812, p. 99.

- ^F.C. and J. Rivington, T. Payne, Wilkie and Robinson: The Chronicle of Iohn Hardyng, 1812, p. 99

- ^abcM. Philippa e.a. (2003-2009) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits]

- ^abL. Weisgerber, Deutsch als Volksname 1953

- ^Rawson, Hugh, Wicked Words, Crown Publishers, 1989.

- ^Hughes Oliphant Old: The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Volume 6: The Modern Age. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, p. 606.

- ^Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p.2

- ^Irwin Richman: The Pennsylvania Dutch Country. Arcadia Publishing, 2004, p.16.

- ^The Pennsylvania Dutch Country, by I. Richman, 2004: "Taking the name Pennsylvania Dutch from a corruption of their own word for themselves," Deutsch, "the first German settlers arrived in Pennsylvania in 1683. By the time of the American Revolution, their influence was such that Benjamin Franklin, among others, worried that German would become the commonwealth's official language."

- ^Moon Spotlight Pennsylvania Dutch Country, by A. Dubrovsk, 2004.

- ^Pennsylvania Dutch Alphabet, by C. Williamson.

- ^abJ. de Vries (1971), Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek

- ^abL. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102–103

- ^L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 98-110.

- ^A. Duke: Dissident Identities in the Early Modern Low Countries (2016)

- ^L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102.

- ^M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal: Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p. 30.

- ^abcG.A.R. de Smet, Die Bezeichnungen der niederländischen Sprache im Laufe ihrer Geschichte; in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 37 (1973), p. 315-327

- ^"L.H. Spiegel: Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst (1584)".Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2021.Retrieved2 February2021.

- ^L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102–103.

- ^M. Philippa e.a. (2003–2009) Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits]

- ^M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal: Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p. 82.

- ^Peters, Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier; translated by Elizabeth Fackelman; translation revised and edited by Edward (1999).The promised lands the Low Countries under Burgundian rule, 1369–1530.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 85.ISBN0-8122-0070-5.Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021.Retrieved3 October2020.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Elton, G. R. (2 August 1990).The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 2, The Reformation, 1520–1559.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521345361.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2023.Retrieved13 October2016.

- ^Rijpma & Schuringa,Nederlandse spraakkunst,Groningen 1969, p. 20.)

- ^M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal: Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p.29.

- ^"Netherlandish",The Free Dictionary,archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2020,retrieved1 August2020

- ^Frans, Claes (1970)."De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw".Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde(86): 297.Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2016.Retrieved13 March2016.

- ^Pérez, Yolanda Robríguez (2008).The Dutch Revolt through Spanish eyes: self and other in historical and literary texts of Golden Age Spain (c. 1548–1673)(Transl. and rev. ed.). Oxford: Peter Lang. p. 18.ISBN978-3-03911-136-7.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2023.Retrieved3 October2020.

- ^"entry Flēmish".Middle English Dictionary(MED).Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016.Retrieved6 April2016.

- ^"MED, entry" Flēming "".Quod.lib.umich.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016.Retrieved17 October2013.

- ^"entry Flemish".Online Etymological Dictionary.Etymonline.Archivedfrom the original on 19 April 2016.Retrieved6 April2016.which citesFlemischeas an Old Frisian form; but cf."entry FLĀMISK, which givesflēmisk".Oudnederlands Woordenboek (ONW).Gtb.inl.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2016.Retrieved6 April2016.

- ^"Entry VLAENDREN; ONW, entry FLĀMINK; Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT), entry VLAMING".Vroeg Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek (VMNW).Gtb.inl.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2021.Retrieved6 April2016.

- ^ONW, entry FLĀMISK.

- ^"Guardian and Observer style guide: H".The Guardian.London. 19 December 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2013.Retrieved1 July2010.

- ^ab"Dutch government ditches Holland to rebrand as the Netherlands".the Guardian.4 October 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 11 June 2022.Retrieved1 June2022.

- ^"Why Dutch Officials Want You to Forget the Country of Holland".The New York Times.New York City. 13 January 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2020.Retrieved15 January2020.

- ^Netherlands TourismArchived7 July 2022 at theWayback Machine"Holland vs Netherlands – Is the Netherlands the same as Holland?"

- ^"Holland vs Netherlands: Everything you need to know".Explore Holland.17 January 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2020.Retrieved17 January2020.

- ^"Holland or the Netherlands?".The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived fromthe originalon 11 July 2010.Retrieved2 July2010.

- ^(in Dutch)Article on website of First ChamberArchived4 March 2016 at theWayback Machine

- ^Prevenier, W.;Uytven, R. van;Poelhekke, J. J.; Bruijn, J. R.; Boogman, J. C.; Bornewasser, J. A.; Hegeman, J. G.; Carter, Alice C.;Blockmans, W.;Brulez, W.;Eenoo, R. van (6 December 2012).Acta Historiae Neerlandicae: Studies on the History of The Netherlands VII.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 83–87.ISBN978-94-011-5948-7.Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2023.Retrieved3 October2020.

- ^For example, the map "Belgium Foederatum" byMatthaeus Seutter,from 1745, which show the current Netherlands.[2]Archived25 August 2012 at theWayback Machine

- ^abFrans, Claes (1970)."De benaming van onze taal in woordenboeken en andere vertaalwerken uit de zestiende eeuw".Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde(86): 296.Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2016.Retrieved13 March2016.

- ^"Le Dictionnaire - Définition batavisme et traduction".le-dictionnaire.Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2016.Retrieved13 March2016.

- ^"Le Dictionnaire - Définition batave et traduction".le-dictionnaire.Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2016.Retrieved13 March2016.

- ^De Koning, Jan (2003).Why did they leave? Why did they stay? On continuity versus discontinuity from Roman times to Early Middle Ages in the western coastal area of the Netherlands. In: Kontinuität und Diskontinuität: Germania inferior am Beginn und am Ende der römischen Herrschaft; Beiträge des deutsch-niederländischen Kolloquiums in der Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, (27. bis 30.6.2001).Walter de Gruyter. pp. 53–83.ISBN9783110176889.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2023.Retrieved3 October2020.

- ^Vaan, Michiel de (15 December 2017).The Dawn of Dutch: Language contact in the Western Low Countries before 1200.John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 42–44.ISBN9789027264503.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2023.Retrieved3 October2020.

- ^Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and TraditionArchived6 April 2023 at theWayback Machine,Volume 13 van Amsterdam archaeological studies, redacteurs: Ton Derks, Nico Roymans, Amsterdam University Press, 2009,ISBN90-8964-078-9,pp. 332–333

- ^Dijkstra, Menno (2011).Rondom de mondingen van Rijn & Maas. Landschap en bewoning tussen de 3e en 9e eeuw in Zuid-Holland, in het bijzonder de Oude Rijnstreek(in Dutch). Leiden: Sidestone Press. p. 386.ISBN978-90-8890-078-5.Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2023.Retrieved5 March2021.