Thalassocracy

| Part of thePolitics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

Athalassocracyorthalattocracy,[1]sometimes alsomaritime empire,is a state with primarily maritime realms, anempireat sea, or a seaborne empire.[2]Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples of this were thePhoenicianstates ofTyre,SidonandCarthage;theItalianmaritime republicsofVeniceandGenoaof theMediterranean;theChola dynastyofTamil NaduinIndia;theOmani EmpireofArabia;and theAustronesianempires ofSrivijayaandMajapahitinMaritime Southeast Asia.Thalassocracies can thus be distinguished from traditional empires, where a state's territories, though possibly linked principally or solely by thesea lanes,generally extend into mainland interiors[3][4]in atellurocracy( "land-based hegemony" ).[5]

The termthalassocracycan also simply refer tonaval supremacy,in either military or commercial senses. TheAncient Greeksfirst used the wordthalassocracyto describe the government of theMinoan civilization,whose power depended on its navy.[6]Herodotusdistinguished sea-power from land-power and spoke of the need to counter the Phoenician thalassocracy by developing a Greek "empire of the sea".[7]

Its realization and ideological construct is sometimes calledmaritimism(cf.PluricontinentalismorAtlanticism), contrastingcontinentalism(cf.Eurasianism).

Origin of the concept: Eusebius' list[edit]

Thalassocracy was a resurrection of a word known from a very specific classical document, which British classical scholarJohn Linton Myrestermed "the List of Thalassocracies".[8]: 87–88 The list was in theChronicon,a work ofuniversal historyofEusebius,an early 4th century bishop ofCaesarea Maritima.Eusebius categorized several historical polities in the Mediterranean as "sea-controlling", and listed them in a chronology.[9]

The list includes a successive series of "thalassocracies", begins from theLydiansafter the fall ofTroy,and ends withAegina,each controlled the sea for a number of years. The list therefore presents a series of the successive exclusive naval domains, as the total control of the seas changed hands between these thalassocracies.[10]Since it does not mention Aegina's final submission of its naval force to Athens, the original list was likely compiled before the consolidation of the Athenian-ledDelian League.[11]

Eusebius' list survived through fragments ofDiodorus Siculus' works, while also appeared in 4th-century theologian and historianJerome'sChronicon,[12]and Byzantine chroniclerGeorge Syncellus'Extract of Chronography.German classical scholarChristian Gottlob Heynereconstructed the list through fragments in 1771.[13]The list was then further surveyed by John Myres in 1906-07 and extensively studied by Molly Miller in the 1970s.[14]

History and examples[edit]

Indo-Pacific[edit]

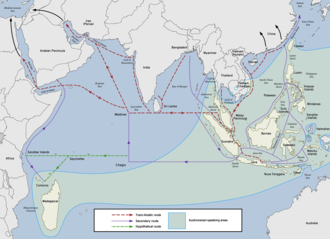

TheAustronesian peoplesofMaritime Southeast Asiadeveloped theIndian Ocean's first true maritime trade network.[15]They established trade routes withSouthern IndiaandSri Lankaas early as 1500 BC, ushering in an exchange of material culture (likecatamarans,outrigger boats,lashed-lugandsewn-plank boats,andpaan) andcultigens(likecoconuts,sandalwood,bananas,andsugarcane); as well as connecting the material cultures ofIndiaandChina.Indonesiansin particular traded in spices (mainlycinnamonandcassia) withEast Africa,usingcatamaranand outrigger boats and sailing with the help of theWesterliesin the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded west toAfricaand theArabian Peninsula,resulting in the Austronesian colonization ofMadagascarby the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued into historic times, later becoming theMaritime Silk Road.[15][16][17][18][19]

The first thalassocracies in the Indo-Pacific region began to emerge around the 2nd century AD, through the rise ofemporiaexploiting the prosperous trade routes betweenFunanandIndiathrough theMalacca Straitusing advanced Austronesian sailing technologies. Numerous coastal city-states emerged, centered on trading ports built near or aroundriver mouthswhich allowed easy access to goods from inland for maritime trade. These city-states established commercial networks with other trading centers inSoutheast Asiaand beyond. Their rulers also graduallyIndianizedby adopting the social structures and religions of India to consolidate theirpower.[20]

The thalassocratic empire ofSrivijayaemerged by the 7th century through conquest and subjugation of neighboring thalassocracies. These includedMelayu,Kedah,Tarumanagara,andMataram,among others. These polities controlled the sea lanes in Southeast Asia and exploited the spice trade of theSpice Islands,as well as maritime trade-routes betweenIndiaandChina.[20]Srivijaya was in turn subjugated bySinghasariaround 1275, before finally being absorbed by the successor thalassocracy ofMajapahit(1293–1527).[21]

TheArakkalAli Rajas ofKannur,Keralaare another example. Ali Moossa, the fifth ruler is said to have conquered some of the Maladweep (Maldives) islands in 1183-84 CE.

The connection with the Maldives andLakshadweep(Laccadives) was well-known to the Portuguese and other Europeans, with the 9° channel separating Minicoy from the Laccadive group being referred to as the 'Mammali’s Channel' after the Arakkal kings. Even during the beginning of the 16th century, the king of Maldives was a tributary of this House. The Jagir of Laccadive islands, received by the Ali Rajas fromKolathirisin the 16th century, enhanced the status of the House.[22]Kannur (Cannanore) could effectively be characterised as a Muslim thalassocracy, acknowledging that the religious identity of the Ali Rajas had a significant role in their political prominence. A link can be made of the income from importing horses from West Asia to the political power of the Ali Rajas throughout the sixteenth century.[23]

Europe and the Mediterranean[edit]

Ancient maritime-centered or seaborne powers in the Mediterranean includePhoenicians,Athens(Delian League),Carthage,Liburniansand to a lesser degreeAeginaandRhodes.[24]

TheMiddle Agessaw multiple thalassocracies, often land-based empires which controlled areas of the sea, the best known of them were theRepublic of Venice,theRepublic of Genoaand theRepublic of Pisa;the others were: theDuchy of Amalfi,theRepublic of Ancona,theRepublic of Ragusa,theDuchy of Gaetaand theRepublic of Noli.They were known asmaritime republics,controlling trade and territories in the Mediterranean Sea for centuries. These contacts were not only commercial, but also cultural and artistic. They also had an essential role in theCrusades.[25][26][27]

The Venetian republic was conventionally divided in the fifteenth century into theDogadoof Venice and the Lagoon, theStato di Terrafermaof Venetian holdings in northern Italy, and theStato da Màrof the Venetian outlands bound by the sea. According to the French historianFernand Braudel,Venice was a scattered empire, a trading-post empire forming a longcapitalistantenna.[28]

From the 12th to the 15th century the Genoese Republic had the monopoly on theWestern Mediterraneantrade, establishing colonies and trading posts in numerous countries, and eventually came to control regions in the Black Sea as well. It was also one of the largest naval powers of Europe during theLate Middle Ages.[25][29]

TheEarly Middle Ages(c.500–1000 AD) saw many of the coastal cities ofSouthern Italydevelop into minor thalassocracies whose chief powers lay in their ports and in their ability to sail navies to defend friendly coasts and to ravage enemy ones. These include the duchies ofGaetaandAmalfi.[30][31]

InNorthern Europe,Kingdom of the Isleslasted from the 9th to 13th centuries AD, and comprised theIsle of Man,theHebridesand other islands off the coast ofGreat Britain.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, theCrown of Aragonwas also a thalassocracy controlling a large portion of present-day easternSpain,parts of what is nowsouthern Franceand other territories in the Mediterranean. The extent of theCatalan languageis a result of this; it's spoken inAlgheroon Sardinia.[32]

Transcontinental[edit]

With the modern age, theAge of Explorationsaw some transcontinental thalassocracies emerge. Anchored in their European territories, several nations established colonial empires held together by naval supremacy. First among them chronologically was thePortuguese Empire,followed soon by theSpanish Empire,which was challenged by theDutch Empire,itself replaced on the high seas by theBritish Empire,which had large landed possessions held together by the Royal Navy. With naval arms-races (especially betweenGermanyandBritain), the end of colonialism, and the winning of independence by many colonies, European thalassocracies, which had controlled the world's oceans for centuries, diminished—though Britain's power-projection in theFalklands Warof 1982 demonstrated continuing thalassocratic clout.[33][34]

TheOttoman Empireexpanded from a land-based region to dominate theEastern Mediterraneanand to expandinto the Indian Oceanas a thalassocracy from the 15th century AD.[35]

List of historical thalassocracies[edit]

- Ajuran Sultanate

- Ancient Carthage

- Arakkal kingdom

- British Empire

- Bruneian Sultanate (1368–1888)(Old Brunei)

- Champa

- Chola Empire

- Crown of Aragon

- Dál Riata

- Delian League

- Demak Sultanate

- Denmark–Norway

- Doric Hexapolis

- Dutch Empire

- Empire of Japan

- Frisian Kingdom

- Hanseatic League

- Johor Sultanate

- Kedah

- Kediri Kingdom

- Kilwa Sultanate

- Kingdom of the Isles

- Liburnia

- Majapahit

- Malacca Sultanate

- Maratha Empire

- Maritime republics

- Maynila

- Mataram Kingdom

- Melayu Kingdom

- Minoan civilization

- Muscat and Oman

- North Sea Empire

- Norwegian Empire

- Omani Empire

- Phoenicia

- Portuguese Empire

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Republic of Pirates

- Republic of Venice

- Ryukyu Kingdom

- Singhasari

- Spanish Empire

- Srivijaya

- Sultanate of Gowa

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Sultanate of Ternate

- Sultanate of Tidore

- Swedish Empire

- Tarumanagara

- Tundun Kingdom

- Tungning Kingdom

- Tuʻi Tonga Empire

- Yapese Empire

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^(fromClassical Greek:θάλασσα,romanized:thalassa,Attic Greek:θάλαττα,romanized:thalatta,transl. 'sea',andAncient Greek:κρατεῖν,romanized:kratein,lit. 'power'; givingKoinē Greek:θαλασσοκρατία,romanized:thalassokratia,lit. 'sea power'),

- ^

Alpers, Edward A. (2013).The Indian Ocean in World History.New Oxford World History. Oxford University Press. p. 80.ISBN978-0199929948.Retrieved2016-02-06.

Portugal's was in every sense a seaborne empire or thalassocracy.

- ^P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (1977).The Cambridge History of Islam.Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–.ISBN978-0-521-29137-8.

- ^Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (2015).A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400–1830.Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–.ISBN978-0-521-88992-6.

- ^Lukic, Rénéo; Brint, Michael, eds. (2001).Culture, politics, and nationalism in the age of globalization.Ashgate. p. 103.ISBN978-0754614364.Retrieved2015-10-12.

- ^ D. Abulafia, "Thalassocracies", in P. Horden – S. Kinoshita (eds.),A Companion to Mediterranean History,Oxford, 2014, pp. 139–153, here 139–140.

- ^A. Momigliano, "Sea-Power in Greek Thought",The Classical Review,May 1944, 1–7.

- ^Myres, John L. (1906). "On the 'List of Thalassocracies' in Eusebius".The Journal of Hellenic Studies.26:84–130.doi:10.2307/624343.JSTOR624343.S2CID163998082.

- ^"Eusebius: Chronicle".attalus.org.Retrieved28 May2017.

- ^InChristian Gottlob Heyne's words, "to thalattokratize" is "to rule the sea", not just to hold sea power like any other ruler with a strong navy; the thalassocrat holds the exclusive imperium over the watery domain just as if it were a country, which explains how such a people can "obtain" and "have" the sea.

- ^Myres 1906,pp. 87–88

- ^The relevant section of the Chronicon in Latin may be found at"Hieronymi Chronicon pp.16-187".tertullian.org.Retrieved29 May2017..

- ^Heyne, Christian Gottlob (1771)."Commentario I: Super Castori Epochis etc".Novi Commentarii Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis.

- ^Molly Miller,The Thalassocracies(SUNY Press, 1971)

- ^abcManguin, Pierre-Yves (2016)."Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships".In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.).Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World.Palgrave Macmillan.pp. 51–76.ISBN978-3319338224.

- ^Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974)."Outrigger Ages".The Journal of the Polynesian Society.83(2): 130–140. Archived fromthe originalon 2019-06-08.Retrieved2019-10-15.

- ^Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.).Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts, languages and texts.One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179.ISBN0415100542.

- ^Doran, Edwin B. (1981).Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins.Texas A&M University Press.ISBN978-0890961070.

- ^Blench, Roger (2004)."Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region".Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association.24(The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- ^abSulistiyono, Singgih Tri; Masruroh, Noor Naelil; Rochwulaningsih, Yety (2018)."Contest For Seascape: Local Thalassocracies and Sino-Indian Trade Expansion in the Maritime Southeast Asia During the Early Premodern Period".Journal of Marine and Island Cultures.7(2).doi:10.21463/jmic.2018.07.2.05.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann (2016)."Śrīvijaya Revisited: Reflections on State Formation of a Southeast Asian Thalassocracy".Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient.102(1): 45–95.doi:10.3406/befeo.2016.6231.

- ^Kurup, KKN (1970)."Ali Rajas of Cannanore, English East India Company and Laccadive Islands".Proceedings of the Indian History Congress.32:44–53.JSTOR44138504.Retrieved12 January2024.

- ^Prange, Sebastian.Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast.

- ^Andrew Lambert,Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires and the Conflict That Made the Modern World(Yale University Press, 2020)

- ^ab"Genoa | Geography, History, Facts, & Points of Interest".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-16.

- ^stage."History of Pisa".About Pisa: full tourist guide about the city of Pisa, Tuscany.Retrieved2021-04-16.

- ^"Pisa | Italy".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-16.

- ^Fernand Braudel,The Perspective of the World,vol. III ofCivilization and Capitalism(Harper & Row) 1984:119.

- ^Walton, Nicholas.Genoa, 'La Superba': The Rise and Fall of a Merchant Pirate Superpower.Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^"Amalfi | Italy".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-16.

- ^Gino BenvenutiLe Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia– Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini,Le repubbliche del mare,Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma.

- ^N. Bisson, Thomas (1991).The Medieval Crown of Aragon 'a Short History'.OUP Oxford.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^"Western colonialism – Spain's American empire".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-17.

- ^"British Empire | Countries, Map, At Its Height, & Facts".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-04-17.

- ^

Fattori, Niccolò (2019). "The Conquering Ottoman Merchant".Migration and Community in the Early Modern Mediterranean: The Greeks of Ancona, 1510–1595.Palgrave Studies in Migration History. Cham (Zug): Springer. p. 44.ISBN978-3030169046.Retrieved3 February2020.

The rise of an Ottoman thalassocracy over the eastern half of the Mediterranean [...].