The Nightmare

| The Nightmare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Henry Fuseli |

| Year | 1781 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 101.6 cm × 127 cm (40.0 in × 50 in) |

| Location | Detroit Institute of Arts,Detroit, Michigan |

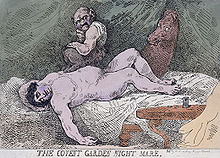

The Nightmareis a 1781oil paintingby Swiss artistHenry Fuseli.It shows a woman in deep sleep with her arms thrown below her, and with a demonic and ape-likeincubuscrouched on her chest. The painting's dreamlike and haunting erotic evocation of infatuation and obsession was a huge popular success.

After its first exhibition, at the 1782Royal Academy of London,critics and patrons reacted with horrified fascination and the work became widely popular, to the extent that it was parodied in political satire and an engraved version was widely distributed. In response, Fuseli produced at least three other versions.

Interpretations vary. The canvas seems to portray simultaneously a dreaming woman and the content of her nightmare. The incubus and horse's head refer to contemporary belief and folklore aboutnightmaresbut have been ascribed more specific meanings by some theorists.[1]Contemporary critics were taken aback by the overt sexuality of the painting, since interpreted by some scholars as anticipatingJungianideas about theunconscious.

Description[edit]

The Nightmaresimultaneously offers both the image of a dream—by indicating the effect of the nightmare on the woman—and a dream image—in symbolically portraying the sleeping vision.[2]It depicts a sleeping woman draped over the end of a bed with her head hanging down, exposing her long neck. She is surmounted by anincubusthat peers out at the viewer. The sleeper seems lifeless and, lying on her back, takes a position then believed to encourage nightmares.[3]Her brilliant coloration is set against the darker reds, yellows, andochresof the background; Fuseli used achiaroscuroeffect to create strong contrasts between light and shade. The interior is contemporary and fashionable and contains a small table on which rests a mirror,phial,and book. The room is hung with red velvet curtains which drape behind the bed. Emerging from a parting in the curtain is the head of a horse with bold, featureless eyes.

For contemporary viewers, the relationship of the incubus and the horse (mare) evoked the notion ofnightmares.The work was likely inspired by thewaking dreamsexperienced by Fuseli and his contemporaries, who found that these experiences related to folkloric beliefs like the Germanic tales about demons and witches that possessed people who slept alone. In these stories, men were visited by horses orhags,giving rise to the terms "hag-riding" and "mare-riding", and women were believed to engage in sex with the devil.[4]The etymology of the word "nightmare", however, does not relate to horses. Rather, the word is derived frommara,aScandinavian mythologicalterm referring to a spirit sent to torment or suffocate sleepers. The early meaning ofnightmareincluded the sleeper's experience of weight on the chest combined withsleep paralysis,dyspnea,or a feeling of dread.[5]The painting incorporates a variety of imagery associated with these ideas, depicting a mare's head and a demon crouched atop the woman.

Sleep and dreams were common subjects for theZürich-born Henry Fuseli, thoughThe Nightmareis unique among his paintings for its lack of reference to literary or religious themes (Fuseli was an ordained minister).[6]His first known painting isJosephInterpreting the Dreams of the Butler and Baker of Pharaoh(1768), and later he producedThe Shepherd's Dream(1798) inspired byJohn Milton'sParadise Lost,andRichard III Visited by Ghosts(1798) based onShakespeare's play.

Fuseli's knowledge of art history was broad, allowing critics to propose sources for the painting's elements in antique, classical, and Renaissance art. According to art critic Nicholas Powell, the woman's pose may derive from theVaticanAriadne,and the style of the incubus fromfigures at Selinunte,an archaeological site inSicily.[4]A source for the woman inGiulio Romano'sThe Dream of Hecuba[b]at thePalazzo del Tehas also been proposed.[7]Powell links the horse to a woodcut by theGerman RenaissanceartistHans Baldungor to the marbleHorse TamersonQuirinal Hill,Rome.[3][7]Fuseli may have added the horse as an afterthought, since a preliminary chalk sketch did not include it. Its presence in the painting has been viewed as avisual punon the word "nightmare" and a self-conscious reference to folklore—the horse destabilises the painting's conceit and contributes to its Gothic tone.[2]

Exhibition[edit]

The painting is housed at theDetroit Institute of Arts.It was first shown at theRoyal Academy of Londonin 1782, where it "excited... an uncommon degree of interest",[8]according to Fuseli's early biographer and friendJohn Knowles.

It remained well-known decades later, and Fuseli painted other versions on the same theme. Fuseli sold the original for twentyguineas,and an inexpensiveengravingbyThomas Burkecirculated widely beginning in January 1783, earning publisher John Raphael Smith more than 500pounds.[8]The engraving was underscored by a short poem byErasmus Darwin,"Night-Mare":[9]

So on his Nightmare through the evening fog

Flits the squab Fiend o'er fen, and lake, and bog;

Seeks some love-wilder'd maid with sleep oppress'd,

Alights, and grinning sits upon her breast.

Darwin included these lines and expanded upon them in his long poemThe Loves of the Plants(1789), for which Fuseli provided the frontispiece:

—Such as of late amid the murky sky

Was mark'd by Fuseli's poetic eye;

Whose daring tints, with Shakspeare's happiest grace,

Gave to the airy phantom form and place.—

Back o'er her pillow sinks her blushing head,

Her snow-white limbs hang helpless from the bed;

Her interrupted heart-pulse swims in death.

O'er her fair limbs convulsive tremors fleet,

Start in her hands, and struggle in her feet;

In vain to scream with quivering lips she tries,

And strains in palsy'd lids her tremulous eyes;

In vain shewillsto run, fly, swim, walk, creep;

The Will presides not in the bower of Sleep.

—On her fair bosom sits the Demon-Ape

Erect, and balances his bloated shape;

Rolls in their marble orbs his Gorgon-eyes,

And drinks with leathern ears her tender cries.[10]

Interpretation[edit]

Contemporary critics often found the work scandalous due to its sexual themes.[citation needed]A few years earlier Fuseli had fallen for a woman named Anna Landholdt in Zürich, while travelling from Rome to London. Landholdt was the niece of his friend, the SwissphysiognomistJohann Kaspar Lavater.Fuseli wrote of his fantasies to Lavater in 1779; "Last night I had her in bed with me—tossed my bedclothes hugger-mugger—wound my hot and tight-clasped hands about her—fused her body and soul together with my own—poured into her my spirit, breath and strength. Anyone who touches her now commits adultery and incest! She is mine, and I am hers. And have her I will.…"[11]

Fuseli's marriage proposal met with disapproval from Landholdt's father, and in any case seems to have been unrequited—she married a family friend soon after.The Nightmare,then, can be seen as a personal portrayal of the erotic aspects of love lost. Art historianH. W. Jansonsuggests that the sleeping woman represents Landholdt and that the demon is Fuseli himself. Bolstering this claim is an unfinished portrait of a girl on the back of the painting's canvas, which may portray Landholdt. Anthropologist Charles Stewart characterises the sleeping woman as "voluptuous,"[5]and one scholar of the Gothic describes her as lying in a "sexually receptive position."[12]InWoman as Sex Object(1972), Marcia Allentuck similarly argues that the painting's intent is to show female orgasm. This is supported by Fuseli's sexually overt and even pornographic private drawings (e.g.,Symplegma of Man with Two Women,1770–78).[4]Fuseli's painting has been considered representative ofsublimatedsexual instincts.[3]Related interpretations of the painting view the incubus as a dream symbol of malelibido,with the sexual act represented by the horse's intrusion through the curtain.[13]Fuseli himself provided no commentary on his painting.

Both the English wordnightmare[14]and its German equivalent,Albtraum(literally'elf dream'), evoke the image of a malevolent being that causes bad dreams by sitting on the chest of the sleeper.[15]

The Royal Academy exhibition brought Fuseli and his painting enduring fame. The exhibition included Shakespeare-themed works by Fuseli, which won him a commission to produce eight paintings for publisherJohn Boydell'sShakespeare Gallery.[13]One version ofThe Nightmarehung in the home of Fuseli's close friend and publisherJoseph Johnson,gracing his weekly dinners for London thinkers and writers.[16]

Fuseli painted other versions ofThe Nightmarefollowing the success of the first; at least three survive. The other important canvas was painted between 1790 and 1791 and is held at theGoethe Museumin Frankfurt.[17]It is smaller than the original, and the woman's head lies to the left; a mirror opposes her on the right. The demon is looking at the woman rather than out of the picture, and it has pointed, catlike ears. The most significant difference in the remaining two versions is an erotic statuette of a couple on the table.[18]

Legacy[edit]

Works by other artists[edit]

The Nightmarewas widely plagiarised, and parodies of it were commonly used for politicalcaricature,byGeorge Cruikshank,[d]Thomas Rowlandson,and others. In these satirical scenes, the incubus afflicts subjects such asNapoleon Bonaparte,Louis XVIII,British politicianCharles James Fox,and Prime MinisterWilliam Pitt.In another example, admiralLord Nelsonis the demon, and his mistressEmma, Lady Hamilton,the sleeper.[18]

While some observers have viewed the parodies as mocking Fuseli, it is more likely thatThe Nightmarewas simply a vehicle for ridicule of the caricatured subject.[19]The Danish painter,Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard,whom Fuseli had met in Rome, produced his own version ofThe Nightmare(Danish:Mareridt) which develops on the eroticism of Fuseli's work. Abildgaard's painting shows two naked women asleep in the bed; it is the woman in the foreground who is experiencing the nightmare and the incubus—which is crouched on the woman's stomach, facing her parted legs—has its tail nestling between her exposed breasts.[20]

Yje German-Danish painterFitlev Blunckcreated another version of the painting in 1846 (NivaagaardNivaagaard Museum).

Influence on literature[edit]

The Nightmarelikely influencedMary Shelleyin a scene from her famousGothic novelFrankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus(1818). Shelley would have been familiar with the painting; her parents,Mary WollstonecraftandWilliam Godwin,knew Fuseli. The iconic imagery associated with the Creature's murder of the protagonist Victor's wife seems to draw from the canvas: "She was there, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features half covered by hair."[11]The novel and Fuseli's biography share a parallel theme: just as Fuseli's incubus is infused with the artist's emotions in seeing Landholdt marry another man, Shelley's monster promises to get revenge on Victor on the night of his wedding. Like Frankenstein's monster, Fuseli's demon symbolically seeks to forestall a marriage.[11]

Edgar Allan Poemay have evokedThe Nightmarein his short story "The Fall of the House of Usher"(1839). His narrator compares a painting hanging in Usher's house to a Fuseli work, and reveals that an" irrepressible tremor gradually pervaded my frame; and, at length, there sat upon my heart an incubus of utterly causeless alarm ".[21]Poe and Fuseli shared an interest in the subconscious; Fuseli is often quoted as saying, "One of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams".[21]

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries[edit]

Fuseli'sNightmarereverberated with twentieth-century psychological theorists. In 1926, American writerMax Eastmanpaid a visit toSigmund Freudand claimed to have seen a print ofThe Nightmaredisplayed next toRembrandt'sThe Anatomy Lessonin Freud'sViennaapartment. Psychoanalyst and Freud biographerErnest Joneschose another version of Fuseli's painting as thefrontispieceof his bookOn the Nightmare(1931); however, neither Freud nor Jones mentioned these paintings in their writings about dreams.Carl JungincludedThe Nightmareand other Fuseli works in hisMan and His Symbols(1964).[22]

Tate Britainheld an exhibition titledGothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imaginationbetween 15 February and 1 May 2006, with theNightmareas the central exhibit. The catalogue indicated the painting's influence on films such as the originalFrankenstein(1931) andThe Marquise of O(1976). Among modern artists,Balthusincorporated elements ofThe Nightmarein his work (e.g.,The Room(1952–54).[d][23]

The 2015 documentaryThe Nightmaremay be a reference to the painting as it documentssleep paralysissufferers (who often hallucinate creatures sitting on their chest).

Famousdrag queenKatya Zamolodchikovareleased anEPtitledVampire Fitnessin November 2020. The EP cover art is a direct reference to The Nightmare, with Katya portraying both the woman and the demon over her body. She even included a horse statue in one corner of the room. It serves as a modern reinterpretation of the painting, with the woman appearing completely nude, except for a pair of sunglasses.

In February 2021,Amaia Salazar,a postdoctoral researcher and visual artist, conducts intense research on the pictorial representation of sleep paralysis throughout the history of art (18th - 21st century), analysing and discovering similar prototypes and archetypes of artistic representation, inspired by Fuseli's artwork.

In January 2023Martin Rowsonproduced a cartoon, "after Fuseli (and everyone else)", forThe Guardianto comment on the ethical problems of theUK government,with aConservative Partymajority. The cartoon featuresRishi Sunak,Boris Johnson,andNadhim Zahawiplus a horse with a hot water bottle.[24]

Notes[edit]

^b:Web imageofGiulio Romano'sThe Dream of Hecuba.

^c:Web imageof Cruikshank's satirical portraitNapoleon Dreaming in His Cell at the Military College(1814), afterThe Nightmare.

^d:Web imageofBalthus'sThe Room(1952–54).

References[edit]

- ^The etymology of the word "nightmare", however, does not relate to horses. Rather, the word is derived from mara, a Scandinavian mythological term referring to a spirit sent to torment or suffocate sleepers.

- ^abEllis, Markman (2000).The History of Gothic Fiction.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 5–8.ISBN0-7486-1195-9.

- ^abcPalumbo, Donald (1986).Eros in the Mind's Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film.Greenwood Press. pp. 40–42.

- ^abcRusso, Kathleen (1990). "Henry Fuseli" in James Vinson (ed.),International Dictionary of Art and Artistsvol. 2,Art.Detroit: St. James Press; pp. 598–99.ISBN1-55862-001-X.

- ^abStewart, Charles (2002). "Erotic Dreams and Nightmares from Antiquity to the Present".Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute.8(2): 279–309.doi:10.1111/1467-9655.00109.

- ^Ferruccio Busoni."JOHANN HEINRICH FÜSSLI"(in Italian).

- ^abChappell, Miles L. (June 1986). "Fuseli and the 'Judicious Adoption' of the Antique in the 'Nightmare'".The Burlington Magazine.128(999): 420–422.

- ^abKnowles, John (1831).The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, Vol. 1.H. Colburn and R. Bentley. pp.64–65.Retrieved21 October2007.

- ^Moffitt, John F. (2002). "A Pictorial Counterpart to 'Gothick' Literature: Fuseli'sThe Nightmare".Mosaic.35(1). University of Manitoba.

- ^Darwin, Erasmus (1825).The Botanic Garden: A Poem in Two Parts….Jones & Company. p.165.Retrieved21 October2007.

- ^abcWard, Maryanne C. (Winter 2000). "A Painting of the Unspeakable: Henry Fuseli's 'The Nightmare' and the Creation of Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein'".The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association.33(1). Midwest Modern Language Association: 20–31.doi:10.2307/1315115.JSTOR1315115.

- ^Davenport-Hines, Richard (1999).Gothic: Four Hundred Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin.North Point Press. p.235.ISBN0-86547-544-X.

- ^abChu, Petra Ten-Doesschate (2006).Nineteenth Century European Art, 2nd Edition.Prentice Hall Art. p. 81.ISBN0-13-196269-8.

- ^Liberman, Anatoly(2005).Word Origins And How We Know Them.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 87.ISBN978-0-19-538707-0.Retrieved29 March2012.

- ^Bjorvand and Lindeman (2007), pp. 719–720.

- ^Chard, Leslie. "Joseph Johnson: Father of the Book Trade".Bulletin of the New York Public Library78 (1975): 63.

- ^"Room 3—Henry Fuseli (Johann Heinrich Füssli): tales told anew".The Frankfurt Goethe-Museum. Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2007.Retrieved5 October2007.

- ^abMurray, Christopher John (2004).Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850.Taylor & Francis. pp.810–11.ISBN1-57958-423-3.

- ^Tomory, Peter (1972).The Life and Art of Henry Fuseli.New York: Praeger Publishers. p.201.LCCN72077546.

- ^Abildgaard's painting was owned for a time by the poet, dramatist and painterHolger Drachmannand hung in his house inSkagen

- ^abShackelford, Lynne P. (Fall 1986). "Poe's THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER".Explicator.45(1): 18–19.doi:10.1080/00144940.1986.11483955.

- ^Packer, Sharon (2002).Dreams in Myth, Medicine, and Movies.Praeger/Greenwood. pp.42,144.ISBN0-275-97243-7.

- ^Perl, Jed (July–August 2006). "anaTroubled classicism: The hyper personality of Henry Fuseli's work".Modern Painters:80–85.

- ^"Martin Rowson on Rishi Sunak's sleaze nightmares - cartoon".Retrieved23 January2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Recent exhibit and publication:Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Imagination.15 February–1 May 2006.Tate Britain,London.ISBN1-85437-582-2

- Jones, E.On the Nightmare.London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1931.

External links[edit]