Third Dynasty of Ur

Ur III dynasty 𒋀𒀕𒆠 URIM2KI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2112 BC– c. 2004 BC | |||||||||||

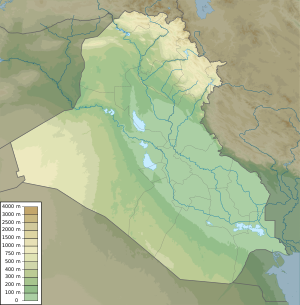

Map showing the Ur III state and its sphere of influence. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ur | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Sumerian,Akkadian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sumerian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Lugal | |||||||||||

•c. 2112–2095 BC (MC) | Ur-Nammu(first) | ||||||||||

•c. 2028–2004 BC (MC) | Ibbi-Sin(last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Established | c. 2112 BC (MC) | ||||||||||

| c. 2004 BC (MC) | |||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 2004 BC (MC) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

TheThird Dynasty of Ur,also called theNeo-Sumerian Empire,refers to a 22nd to 21st centuryBC(middle chronology)Sumerianruling dynasty based in the city ofUrand a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider to have been a nascent empire.

The Third Dynasty of Ur is commonly abbreviated asUr IIIby historians studying the period. It is numbered in reference to previous dynasties, such as theFirst Dynasty of Ur(26-25th century BC), but it seems the once supposed Second Dynasty of Ur was never recorded.[1]

The Third Dynasty of Ur was the last Sumerian dynasty which came to preeminent power inMesopotamia.It began after several centuries of control, exerted first by theAkkadian Empire,and then, after its fall, byGutianand independent Sumerian city-state kings. It controlled the cities ofIsin,Larsa,andEshnunnaand extended as far north asUpper Mesopotamia.

History[edit]

The Third Dynasty of Ur arose some time after the fall of theAkkad Dynasty.The period between the last powerful king of the Akkad Dynasty,Shar-Kali-Sharri,and the first king of Ur III,Ur-Nammu,is not well documented, but most Assyriologists posit that there was a brief "dark age", followed by a power struggle among the most powerful city-states. On the king-lists, Shar-Kali-Sharri is followed by two more kings of Akkad and six in Uruk; however, there are no year names surviving for any of these, nor even any artifacts confirming that any of these reigns was historical — save one artifact forDudu of Akkad(Shar-Kali-Sharri's immediate successor on the list). Akkad's primacy, instead, seems to have been usurped byGutianinvaders from theZagros Mountains,whose kings ruled in Mesopotamia for an indeterminate period (124 years according to some copies of theking list,only 25 according to others). An illiterate and nomadic people, their rule was not conducive to agriculture, nor record-keeping, and by the time they were expelled, the region was crippled by severe famine and skyrocketing grain prices.[citation needed]Their last king,Tirigan,was driven out byUtu-hengalofUruk.

Following Utu-Hengal's reign,Ur-Nammu(originally a general) founded the Third Dynasty of Ur, but the precise events surrounding his rise are unclear. TheSumerian King Liststates that Utu-hengal had reigned for seven years (or 426, or 26 in other copies), although only one year-name for him is known from records, that of his accession, suggesting a shorter reign.

It is possible that Ur-Nammu was originally his governor. There are twostelaediscovered inUrthat include this detail in an inscription about Ur-Nammu's life.

Ur-Nammu rose to prominence as a warrior-king when he crushed the ruler ofLagashin battle, killing the king himself. After this battle, Ur-Nammu seems to have earned the title 'king of Sumer and Akkad.'

Ur's dominance over the Neo-Sumerian Empire was consolidated with the famousCode of Ur-Nammu,probably the first such law-code for Mesopotamia since that ofUrukaginaofLagashcenturies earlier.

Many significant changes occurred in the empire underShulgi's reign. He took steps to centralize and standardize the procedures of the empire. He is credited with standardizing administrative processes, archival documentation, the tax system, and the national calendar. He captured the city ofSusaand the surrounding region, topplingElamitekingKutik-Inshushinak,while the rest of Elam fell under control ofShimashki dynasty.[2]

The military and conquests of Ur III[edit]

In the last century of the 3rd millennium BCE, it is believed that the kings of Ur waged several conflicts around the frontiers of the kingdom. These conflicts are believed to have been influenced by the king of Akkad. As there is little evidence of how the kings organized their forces, it is unclear whether defensive forces were in the center or outside the kingdom. What is known is that the second ruler of the dynasty,Šulgiachieved some expansion and conquest. These were continued by his three successors but their conquests are less frequent with time.[3]

At the very height of the expansion of Ur, they had taken territory from southeasternAnatolia(modernTurkey) to the Iranian shore of the Persian Gulf, a testimony to the strength of the dynasty. There are hundreds of texts that explain how treasures were seized by the Ur III armies and brought back to the kingdom after many victories. In some texts, it also appears that the Shulgi campaigns were the most profitable for the kingdom, although it is likely that the kings and temples of Ur were primarily those that benefited from the spoils of war.[3]

Conflicts with northeastern mountain tribes[edit]

The rulers of Ur III were often in conflict with the highland tribes of theZagros mountainarea who dwelled in the northeastern portion of Mesopotamia. The most important of these tribes were theSimurrumand theLullubitribal kingdoms.[4][5]They were also often in conflict withElam.

Military rulers of Mari[edit]

In the northern area ofMari,Semitic military rulers called theShakkanakkusapparently continued to rule contemporaneously with the Third Dynasty of Ur, or possibly in the period that just preceded it,[6]with rulers such as military governors likePuzur-Ishtar,who was probably contemporary withAmar-Sin.[7][8]

Timeline of rulers[edit]

Assyriologists employ many complicated methods for establishing the most precise dates possible for this period, but controversy still exists. Generally, scholars use either the conventional (middle, generally preferred) or the low (short) chronologies. They are as follows:

| Ruler | Middle Chronology | Short Chronology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Utu-hengal) | c. 2119– c. 2112 BC | c. 2055– c. 2048 BC | |

| Ur-Nammu | c. 2112– c. 2094 BC | c. 2048– c. 2030 BC | |

| Shulgi | c. 2094– c. 2046 BC | c. 2030– c. 1982 BC | |

| Amar-Sin | c. 2046– c. 2037 BC | c. 1982– c. 1973 BC | |

| Shu-Sin | c. 2037– c. 2028 BC | c. 1973– c. 1964 BC | |

| Ibbi-Sin | c. 2028– c. 2004 BC | c. 1964– c. 1940 BC |

The list of the Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur with the length of their reigns, appears on a cuneiform document listing the kings of Ur andIsin,the "List of Reigns of Kings of Ur and Isin" (MS 1686). The list explains: "18 yearsUr-Namma[was] king, 48 yearsShulgi[was] king, 9 yearsAmar-Suen,9 yearsSu-Suen,24 yearsIbbi-Suen."[11]

Fall of Ur III[edit]

The power of the Neo-Sumerians was waning.Ibbi-Sinin the 21st century launched military campaigns intoElam,but did not manage to penetrate far into the country. In 2004/1940 BC (middle/short chronology respectively), the Elamites, allied with the people ofSusaand led byKindattu,king of the ElamiteShimashki dynasty,was able to surround Ur and managed to sackUr(early summer?)[12]and leadIbbi-Sininto captivity, ending thethird dynasty of Ur.After this victory, the Elamites destroyed the kingdom, and ruled through military occupation for the next 21 years.[13][14]

Mesopotamiathen fell underAmoriteinfluence. The Amorite kings of theDynasty of Isinformedsuccessor statesto Ur III, starting theIsin-Larsa period.They managed to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuilt the city, and returned the statue ofNannathat the Elamites had plundered. The Amorites were nomadic tribes from the northernLevantwho wereNorthwest Semiticspeakers, unlike the nativeAkkadiansof southern Mesopotamia andAssyria,who spokeEast Semitic.By around the19th century BC,much of southern Mesopotamia was occupied by the Amorites. The Amorites at first did not practice agriculture, preferring a semi-nomadic lifestyle, herding sheep. Over time, Amorite grain merchants rose to prominence and established their own independent dynasties in several south Mesopotamian city-states, most notablyIsin,Larsa,Eshnunna,Lagash,and later, foundingBabylonas a state.

Dating systems[edit]

When Kings of the Third Ur dynasty ruled they had specific dates and names for each period of their rule. One example was "the year of Ur-nammu king," which marked Ur-Nammu's coronation. Another important time was the year named "The threshed grain of Largas." This year name references an event in which Ur-Nammu attacked the territory of Largas and took grain back to Ur. Another year-name that has been discovered was the year that Ur-Nammu's daughter becameenof the god Nanna and was renamed with the priestess-name of En-Nirgal-ana. This designation asenof Nanna makes the year's designation almost certain.[15]

Social and political organization[edit]

Political organization[edit]

The Ur III state followed apatrimonialsystem. The state was organized into a hierarchical pyramid of households with the royal household at the top. As described by Steinkeller it was a network of households linked together by mutual rights and obligations. All resources of the state were exclusively owned by the royal household. All inferior households were considered dependants of the higher ones. Inferior households contributed corvee labour to the royal household and received economic support, land, and protection in return.[16][17][18]

In each province, administrative and economic responsibility were split between two households: one headed by a governor (ensi) and one headed by a general (Šagina) who represented the crown.

Each province had a redistribution center where provincial taxes, calledbala,would all go to be shipped to the capital. The bala tax worked on a rotating basis, with only one province supporting the kingdom at a time. Each province would support the kingdom for an amount of time determined by the size of their economy. Taxes could be paid in various forms, from crops to livestock to land.[16][19]The government would then apportion out goods as needed, including funding temples and giving food rations to the needy.

The city of Nippur and its importance[edit]

The city ofNippurwas one of the most important cities in the Third Dynasty of Ur. Nippur is believed to be the religious center of Mesopotamia. It was home to the shrine ofEnlil,who was the lord of all gods. This was where the God Enlil spoke the king's name and was calling the king to his existence. This was used as a legitimacy for every king in order to secure power. The city is also believed to be a place where people would often take disputes according to some tablets that were found near the city. Politically it is hard to say how significant Nippur was because the city had no status as a dynastic or military power. However, the fact that Nippur never really gave kings any real political or military advantages suggests to some that it was never really conquered. The city itself was more viewed as "national Cult Center." Because it was viewed this way it was thought that any conquest of the city would give the Mesopotamian rulers unacceptable political risks. Also as the city was seen as a holy site this enabled Nippur to survive numerous conflicts that wiped out many other cities in the region.[20]

Social system[edit]

This is an area where scholars have many different views. It had long been posited that the common laborer was nothing more than a serf, but new analysis and documents reveal a possible different picture. Gangs of labourers can be divided into various groups.

Certain groups indeed seem to work under compulsion. Others work in order to keep property or get rations from the state. Still other laborers were free men and women for whom social mobility was a possibility. Many families travelled together in search of labor. Such laborers could amass private property and even be promoted to higher positions. This is quite a different picture of a laborer's life than the previous belief that they were afforded no way to move out of the social group they were born into.

Slaves also made up a crucial group of labor for the state. One scholar[who?]estimates that 2/5 of chattel slaves mentioned in documents were not born slaves but became slaves due to accumulating debt, being sold by family members, or other reasons. However, one surprising feature of this period is that slaves seem to have been able to accumulate some assets and even property during their lifetimes such that they could buy their freedom. Extant documents give details about specific deals for slaves' freedoms negotiated with slaveowners.

An early code of law[edit]

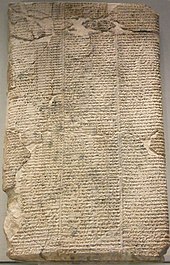

One salient feature of Ur III is its establishment of one of the earliest known law-codes, theCode of Ur-Nammu.It is quite similar to the famousCode of Hammurabi,resembling its prologue and bodily structure. Extant copies, written inOld Babylonian,exist fromNippur,Sippar,and alsoUritself. Although the prologue creditsUr-Nammu,the author is still somewhat under dispute; some scholars attribute it to his son,Shulgi.[22]

The prologue to the law-code, written in the first person, established the king as the beacon of justice for his land, a role that previous kings normally did not play. He claims to want justice for all, including traditionally unfortunate groups in the kingdom like the widower or the orphan.

Most legal disputes were dealt with locally by government officials called mayors, although their decision could be appealed and eventually overturned by the provincial governor. Sometimes legal disputes were publicly aired with witnesses present at a place like the town square or in front of the temple. However, the image of the king as the supreme judge of the land took hold, and this image appears in many literary works and poems. Citizens sometimes wrote letters of prayer to the king, either present or past.

Industry and commerce[edit]

The Ur III kings oversaw many substantial state-run projects, including intricateirrigationsystems and centralization of agriculture. An enormous labor force was amassed to work in agriculture, particularly in irrigation, harvesting, and sowing.

Textiles were a particularly important industry in Ur during this time. Thetextile industrywas run by the state. Many men, women, and children alike were employed to producewoolandlinenclothing.The detailed documents from the administration of this period exhibit a startling amount of centralization; some scholars have gone so far as to say no other period in Mesopotamian history reached the same level.

Trade with the Gulf Region[edit]

Trade was very important to the Ur Dynasty because it was a way to ensure that the empire had enough ways to grow its wealth and care for those Ur ruled. One of the areas that Mesopotamia traded with was the Persian Gulf area, trading mostly raw materials such as metal, wood, ivory, and also semi-precious stones. One specific kind of item traded with the two regions were conch shells. These were made by craftsmen who would turn them into lamps and cups dating back to the 3rd millennium. They have been discovered in graves, palaces, temples, and even residential homes. The fact that this item was mostly found in upper class contexts could show that only the wealthy at the time had access to the item. Additionally, Ur consumed jewelry, inlays, carvings, and cylinder seals in significant amounts. The high demand for these items shows a heavy trade relationship with the Gulf region.[23]

Commercial relations with the Indus[edit]

Evidence for imports from the Indus toUrcan be found from around 2350 BC.[24]Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularlyTrubinella PyrumandFasciolaria Trapezium,have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500-2000 BC.[25]Several Indus seals with Harappan script have also been found in Mesopotamia, particularly inUrandBabylon.[26][27][28][29]About twenty seals have been found from the Akkadian and Ur III sites, that have connections withHarappaand often use theIndus script.[30]

These exchanges came to a halt with the decline of theIndus valley civilizationafter around 1900 BC.[31]

Art and culture[edit]

Sumerian dominated the cultural sphere and was the language of legal, administrative, and economic documents, while signs of the spread of Akkadian could be seen elsewhere. New towns that arose in this period were virtually all given Akkadian names. Culture also thrived through many different types ofart forms.

Literature[edit]

Sumerian texts were mass-produced in the Ur III period; however, the word 'revival' or 'renaissance' to describe this period is misleading because archaeological evidence does not offer evidence of a previous period of decline.[33]Instead, Sumerian began to take on a different form. As the Semitic Akkadian language became the common spoken language, Sumerian continued to dominate literature and also administrative documents. Government officials learned to write at special schools that used only Sumerian literature.

Some scholars believe that the UrukEpic of Gilgameshwas written down during this period into its classicSumerianform. The Ur III Dynasty attempted to establish ties to the early kings of Uruk by claiming to be their familial relations.

For example, the Ur III kings often claimed Gilgamesh's divine parents,NinsunandLugalbanda,as their own, probably to evoke a comparison to the epic hero.

Another text from this period, known as "The Death of Urnammu", contains an underworld scene in which Ur-Nammu showers "his brother Gilgamesh" with gifts.

-

Cuneiform tablet impressed with cylinder seal. Receipt of goats,c. 2040 BC.Neo-Sumerian (drawing).[35]

-

Administrative Tablet, Third Dynasty of Ur, 2026 BC.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"The so-called Second Dynasty of Ur is a phantom and is not recorded in the SKL" inFrayne, Douglas (2008).Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC).University of Toronto Press. p. 910.ISBN978-1-4426-9047-9.

- ^Encyclopedia Iranica: Elam - Simashki dynasty, F. Vallat

- ^abLafont, Bertrand. "The Army of the Kings of Ur: The Textual Evidence".Cuneiform Digital Library Journal.

- ^Eidem, Jesper (2001).The Shemshāra Archives 1: The Letters.Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 24.ISBN9788778762450.

- ^Frayne, Douglas (1990).Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC).University of Toronto Press. pp. 707 ff.ISBN9780802058737.

- ^Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020).Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins.Getty Publications. p. 14.ISBN978-1-60606-649-2.

- ^Leick, Gwendolyn (2002).Who's Who in the Ancient Near East.Routledge.ISBN978-1-134-78796-8.

- ^Durand, M.L. (2008).Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible: TELL HARIRI/MARI: TEXTES(PDF).p. 227.

- ^ab"Hash-hamer Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu".British Museum.

- ^Barton, George A. (George Aaron) (1918).Miscellaneous Babylonian inscriptions.New Haven, Yale University Press. pp. 45–50.

- ^George, A. R.Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists(PDF).pp. 206–210.

- ^Abram(PDF).Cary Cook. 2007. p. 1.

- ^Bryce, Trevor (2009).The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire.Routledge. p. 221.ISBN9781134159079.

- ^D. T. Potts (12 November 2015).The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State.Cambridge University Press. p. 133.ISBN978-1-107-09469-7.

- ^Frayne, Douglas (1997).Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC).Canadian Electronic Library.

- ^abSteinkeller, Piotr (March 2021). "The Sargonic and Ur III Empires".The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume Two: The History of Empires.Oxford University Press. pp. 43–72.ISBN9780197532799.

- ^Notizia, Palmiro (2019)."HOW TO" INSTITUTIONALIZE "A HOUSEHOLD IN UR III ĜIRSU/LAGAŠ: THE CASE OF THE HOUSE OF UR-DUN".Journal of Cuneiform Studies.71:11–12.doi:10.1086/703851.JSTOR48569340.

- ^Garfinkle, Steven (2008). "Was the Ur III state bureaucratic? Patrimonialism and Bureaucracy in the Ur III period".The Growth of an Early State in Mesopotamia: Studies in Ur III Administration.Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 55–61.

- ^Podany, Amanda (December 2013). "The Third Dynasty of Ur, 2193–2004 bce".The Ancient Near East: A Very Short Introduction.Oxford University Press. pp. 58–61.

- ^Fish, T. (1938). "The Sumerian City Nippur in the Period of the Third Dynasty of Ur".Iraq.5:157–179.doi:10.2307/4241631.JSTOR4241631.S2CID193037384.

- ^John Bagnell Bury; et al. (1925).The Cambridge Ancient History.Cambridge University Press.p. 607.ISBN0-521-07791-5.

- ^Potts, D. T. (1999).The Archaeology of Elam.Cambridge University Press. p. 132.ISBN9780521564960.

- ^Edens, Cristopher. "Dynamics of Trade in the Ancient Mesopotamian" World System "".American Anthropologist.New Series: 22.

- ^Reade, Julian E. (2008).The Indus-Mesopotamia relationship reconsidered (Gs Elisabeth During Caspers).Archaeopress. pp. 14–17.ISBN978-1-4073-0312-3.

- ^Gensheimer, T. R. (1984). "The Role of shell in Mesopotamia: evidence for trade exchange with Oman and the Indus Valley".Paléorient.10:71–72.doi:10.3406/paleo.1984.4350.

- ^"Indus stamp-seal found in Ur BM 122187".British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 123208".British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 120228".British Museum. - ^Gadd, G. J. (1958).Seals of Ancient Indian style found at Ur.

- ^Podany, Amanda H. (2012).Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East.Oxford University Press. p. 49.ISBN978-0-19-971829-0.

- ^Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003).Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus.Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 246.ISBN978-1-58839-043-1.

Square-shaped Indus seals of fired steatite have been found at a few sites in Mesopotamia.

- ^McIntosh, Jane (2008).The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives.ABC-CLIO. pp. 182–190.ISBN9781576079072.

- ^Stiebing, William H. (2016).Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture.Routledge. p. 85.ISBN9781315511160.

- ^"Seated figure approached by a goddess leading a worshiper".metmuseum.org.

- ^Cooper, Jerrold S. (2016). "Sumerian literature and Sumerian identity".Problems of canonicity and identity formation in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.Kim Ryholt, Gojko Barjamovic, Københavns universitet, Denmark) Problems of Canonicity and Identity Formation in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (2010: Copenhagen, Denmark) Literature and Identity Formation (2010: Copenhagen. Copenhagen. pp. 1–18.ISBN978-87-635-4372-9.OCLC944087535.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"The Stela of the Flying Angels".The Museum Journal.

- ^abSpar, Ira (1988).Cuneiform Texts in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Volume I Tablets Cones and Bricks of the Third Ur Dynasty(PDF).The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 38, Nb 35.

Further reading[edit]

- Jacob L. Dahl, "The ruling family of Ur III Umma. A Prosopographical Analysis of an Elite Family in Southern Iraq 4000 Years ago", Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten, 2007

- Frayne, Douglas (1997).Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC).University of Toronto Press.ISBN9781442623767– via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Robertson, John F. (1984). "The Internal Political and Economic Structure of Old Babylonian Nippur: The Guennakkum and His 'House'".Journal of Cuneiform Studies.36(2): 145–190.doi:10.2307/1360054.JSTOR1360054.S2CID156528750.

- Sallaberger, Walther; Westenholz, Aage (1999).Mesopotamien. Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit.Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Vol. 160/3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.ISBN3-525-53325-X.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc(2007).A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. Second Edition.Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Malden: Blackwell.ISBN978-1-4051-4911-2.

External links[edit]

- Third Dynasty of Ur

- States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 3rd millennium BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 20th century BC

- Sumer

- Ur

- Middle Eastern royal families

- 22nd-century BC establishments

- Former empires in Asia

- Former monarchies

![Stele of Ur-Nammu, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology.[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Stele_of_Ur-Nammu_%28front_and_back%29.jpg/200px-Stele_of_Ur-Nammu_%28front_and_back%29.jpg)

![Cuneiform tablet impressed with cylinder seal. Receipt of goats, c. 2040 BC, year 7 of Amar-Sin. Neo-Sumerian.[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Cuneiform_tablet_impressed_with_cylinder_seal._Receipt_of_goats%2Cca._2040_B.C._Neo-Summerian.jpg/200px-Cuneiform_tablet_impressed_with_cylinder_seal._Receipt_of_goats%2Cca._2040_B.C._Neo-Summerian.jpg)

![Cuneiform tablet impressed with cylinder seal. Receipt of goats, c. 2040 BC. Neo-Sumerian (drawing).[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/24/Cuneiform_tablet_impressed_with_cylinder_seal._Receipt_of_goats%2Cca._2040_B.C._Neo-Summerian_%28drawing%29.jpg/200px-Cuneiform_tablet_impressed_with_cylinder_seal._Receipt_of_goats%2Cca._2040_B.C._Neo-Summerian_%28drawing%29.jpg)