Thracians

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(April 2022) |

| This article is part ofa serieson |

|

| Thrace |

| Geography |

|---|

| Culture |

| Tribes |

| History |

| Warfare |

| Roman Thrace |

| Mythology |

| Legacy |

TheThracians(/ˈθreɪʃənz/;Ancient Greek:Θρᾷκες,romanized:Thrāikes;Latin:Thraci) were anIndo-European speaking peoplewho inhabited large parts ofSoutheast Europeinancient history.[1][2]Thracians resided mainly inSoutheast Europeinmodern-dayBulgaria,Romania,and northernGreece,but also in north-westernAnatolia (Asia Minor)inTurkey.

The exact origin of the Thracians is uncertain, but it is believed that Thracians descended from a purported mixture ofProto-Indo-EuropeansandEarly European Farmers.[3]

Around the 5th millennium BC, the inhabitants of the eastern region of theBalkansbecame organized in different groups ofindigenous peoplethat were later named by the ancientGreeksunder the single ethnonym of "Thracians".[4][5][6][7]

TheThracian cultureemerged during the earlyBronze Age,which began about 3500 BC.[4][8][9][10]From it also developed theGetae,theDaciansand other regional groups of tribes. Historical and archaeological records indicate that the Thracian culture flourished in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC.[4][11][12]Writing in the 6th century BC, Xenophanes described Thracians as "blue-eyed and red-haired".[13]

According toGreekandRomanhistorians, the Thracians were uncivilized and remained largely disunited, until the establishment of their first permanent state theOdrysian kingdomin the 5th century BC. The Thracian kingdom faced subjugation by theAchaemenid Empirearound the same time. After thePersianswere defeated by the Greeks in thePersian Wars,the Thracians experienced a short period of peace. In the late 4th century BC the Odrysian kingdom lost independence toMacedon,becoming incorporated into the empire, but it regained independence followingAlexander the Great's death.

The Thracians faced conquest by theRomansin the mid 2nd century BC under whom they faced internal strife. They composed major parts of rebellions against the Romans along with the Macedonians until theThird Macedonian War.Beginning in 73 BC,Spartacus,a Thracian warrior from theMaeditribe who was enslaved as agladiatorby the Romans, led arevoltthat posed a significant challenge to Roman authority, prompting a series of military campaigns against it. The aftermath of the rebellion saw thecrucifixionof 6,000 surviving rebels along theAppian Way.

Thracians were described as "warlike"and"barbarians"by theGreeksandRomanssince they were neither Romans nor Greeks but in spite of that they were favored as excellent mercenaries. While the Thracians were perceived as unsophisticated by the Romans and Greeks, their culture was reportedly noted for its sophisticatedpoetryandmusic.[14]Since the 19th century-early 20th century, Bulgaria and Romania have usedArchaeologyto learn more aboutThracian cultureand way of life.

Thracians followed apolytheistic religionwithmonotheisticelements. One of their customs wastattooing,common among both men and women.[15]The Thracians culturally interacted with the peoples surrounding them –Greeks,Persians,ScythiansandCelts[16][17]Thracians spoke the nowextinctThracian languageand shared a common culture.[1]The last reported use of aThracian languagewas bymonksin the 6th century AD. The scientific study of the Thracians is known asThracology.

Etymology

[edit]The first historical record of theethnonymThracianis found in theIliad,where the Thracians are described as allies of theTrojansin theTrojan Waragainst the Ancient Greeks.[18]TheethnonymThraciancomes from Ancient GreekΘρᾷξ(Thrāix;plural Θρᾷκες,Thrāikes) or Θρᾴκιος (Thrāikios;Ionic:Θρηίκιος,Thrēikios), and the toponymThracecomes from Θρᾴκη (Thrāikē;Ionic: Θρῄκη,Thrēikē).[19]These forms are allexonymsas applied by the Greeks.[20]

Mythological foundation

[edit]

InGreek mythology,Thrax(his name simply the quintessential Thracian) was regarded as one of the reputed sons of the godAres.[21]In theAlcestis,Euripidesmentions that one of the names of Ares himself was "Thrax". Since Ares was regarded as the patron of Thrace his golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia inThrace.[22]

Origins

[edit]The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records before they made contact with theGreeks.[23]Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts ofmaterial culture.Leo Klejnidentifies proto-Thracians with themulti-cordoned ware culturethat was pushed away from Ukraine by the advancingtimber grave cultureor Srubnaya. It is generally proposed that a Thracian people developed from a mixture ofindigenous peoplesandIndo-Europeansfrom the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in theEarly Bronze Age[24]when the latter, around 1500 BC, mixed with indigenous peoples.[25]According to one theory, their ancestors migrated in three waves from the northeast: the first in theLate Neolithic,forcing out thePelasgiansandAchaeans,the second in theEarly Bronze Age,and the third around 1200 BC. They reached theAegean islands,ending theMycenaean civilization.They did not speak the same language.[23]The lack of written archeological records left by Thracians suggests that the diverse topography did not make it possible for a single language to form.[23]

Ancient GreekandRomanhistorians agreed that the ancient Thracians were superior fighters; only their constant political fragmentation prevented them from overrunning the lands around the northeasternMediterranean.[26]Although these historians characterized the Thracians as "primitive" partly because they lived in simple, open villages, the Thracians in fact had a fairly advanced culture that was especially noted for its poetry and music. Their soldiers were valued as mercenaries, particularly by theMacedoniansandRomans.[26]

Identity and distribution

[edit]Thracians inhabited parts of the ancient provinces ofThrace,Moesia,Macedonia,Beotia,Attica,Dacia,Scythia Minor,Sarmatia,Bithynia,Mysia,Pannonia,and other regions of theBalkansandAnatolia.This area extended over most of the Balkans region, and theGetaenorth of theDanubeas far as beyond theBugand includingPannoniain the west.[27]

According toEthnica,a geographical dictionary byStephanus of Byzantium,Thrace—the land of the Thracians—was known as Perki (Περκη) and Aria (Αρια) before being named Thrace by the Greeks,[28][29]presumably due to the affiliation of the Thracians with the godAres[30]and Perki is the reflexive name of the god Ares as *Perkʷūnos.[31]

Thucydides[30]mentions about a period in the past, from his point of view, when Thracians had inhabited the region ofPhocis,also known as the location ofDelphi.He dates it to the lifetime ofTereus– mythological Thracian king and son of the godAres.

Due to the lack of historical records that predateClassical Greeceit's presumed that the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until theOdrysian statewas founded in the 5th century BC. In the 1st century BC, duringKing Burebista's rule, emerged the powerful state ofDacia.

Currently, there are about 200 identifiedThracian tribes.[32]The most prominent tribe, theMoesiachieved significant importance during Roman rule.[33]What's notable about the Moesians is that they practiced vegetarianism, feeding themselves on honey, milk, and cheese.[34]

Greek and Roman descriptions

[edit]Thracians were regarded by ancientGreeksandRomansas warlike, ferocious, bloodthirsty, and barbarian.[35][36][37]Platoin hisRepublicgroups them with theScythians,[38]calling them extravagant and high spirited; and in hisLawsportrays them as a warlike nation, grouping them withCelts,Persians,Scythians,IberiansandCarthaginians.[39]Polybiuswrote of Cotys's sober and gentle character being unlike that of most Thracians.[40]Tacitusin hisAnnalswrites of them being wild, savage and impatient, disobedient even to their own kings.[41]The Thracians have been said to have "tattooed their bodies, obtained their wives by purchase, and often sold their children".[37]TheFrenchhistorianVictor Duruyfurther notes that they "considered husbandry unworthy of a warrior, and knew no source of gain but war and theft".[37]He also states that they practicedhuman sacrifice,[37]which has been confirmed by archaeological evidence.[42]

PolyaenusandStrabowrite how the Thracians broke their pacts oftrucewith trickery.[43][44]Polyaneus testifies that the Thracians struck their weapons against each other before battle, "in the Thracian manner".[45]Diegylis,leader of theCaeni,was considered one of the most bloodthirsty chieftains byDiodorus Siculus.AnAthenianclub for lawless youths was named after the thracian tribeTriballi[46]which might be the origin of the wordtribe.

According to ancient Roman sources, theDii[47]were responsible for the worst[48]atrocities in thePeloponnesian War,killing every living thing, including children and dogs inTanagraandMycalessos.[47]TheDiiwould impaleRomanheads on their spears andrhomphaiassuch as in theKallinikosskirmish at 171 BC.[48]Strabo treated the Thracians as barbarians, and held that they spoke the same language as theGetae.[49]Some Roman authors noted that even after the introduction of Latin they still kept their "barbarous" ways.[37]Herodotuswrites that "the thracians sell their children and let their maidens commerce with whatever men they please".[50]

The accuracy and impartiality of these descriptions have been called into question in modern times, given the seeming embellishments in Herodotus's histories, for one.[51][52][53]Archaeologistshave attempted to piece together a fuller understanding of Thracian culture through the study of their artifacts.[54]

Physical appearance

[edit]

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the nameRufusinscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people withred hair[55]which led to associating the name with slaves when theRomansenslaved this particular group.[56]Ancient Greek artwork often depicts Thracians as redheads.[57]Rhesus of Thrace,a mythological Thracian king, was so named because of his red hair and is depicted on Greek pottery as having red hair and a red beard.[57] Ancient Greek writers also described the Thracians as red-haired. A fragment by the Greek poetXenophanesdescribes the Thracians as blue-eyed and red haired:

...Men make gods in their own image; those of the Ethiopians are black and snub-nosed, those of the Thracians have blue eyes and red hair.[58]

BacchylidesdescribedTheseusas wearing a hat with red hair, which classicists believe was Thracian in origin.[59]Other ancient writers who described the hair of the Thracians as red includeHecataeus of Miletus,[60]Galen,[61]Clement of Alexandria,[62]andJulius Firmicus Maternus.[63]

Nevertheless, academic studies[citation needed]have concluded that people often had different physical features from those described by primary sources. Ancient authors described as red-haired several groups of people. They claimed that allSlavs had red hair,and likewise described theScythiansas red haired. According to Beth Cohen, Thracians had "the same dark hair and the same facial features as theAncient Greeks."[64]However, Aris N. Poulianos states that Thracians, like modernBulgarians,belonged mainly to the Aegean anthropological type.[65]

History

[edit]Homeric period

[edit]The earliest known mention of Thracians is in the second song of Homer'sIliad,where the population inhabiting theThracian Chersonesusis said to have participated in theTrojan War,which is believed to have taken place around 12th century BC. This population is referred to with the following name:

"...And Hippothous led the tribes of thePelasgi,that rage with the spear, even them that dwelt in deep-soiledLarisa;these were led by Hippothous and Pylaeus, scion ofAres,sons twain of Pelasgian Lethus, son ofTeutamus.But the Thracians Acamas led andPeirous,the warrior, even all them that the strong stream of the Hellespont encloseth. "[66][67][68]

Archaic period

[edit]The firstGreek coloniesalong the Thracian coasts (first theAegean,then theMarmaraandBlack Seas) were founded in the 8th century BC.[69]Thracians and Greeks lived side-by-side. Ancient sources record a Thracian presence on theAegean islandsand inHellas(the broader "land of theHellenes").[70]

At some point in the 7th century BC, a portion of the ThracianTrerestribe migrated across theThracian Bosporusand invadedAnatolia.[71]In 637 BC, the Treres under their king Kobos (Ancient Greek:ΚώβοςKṓbos;Latin:Cobus), in alliance with theCimmeriansand theLycians,attacked the kingdom ofLydiaduring the seventh year of the reign of the Lydian kingArdys.[72]They defeated theLydiansand captured the capital city of Lydia,Sardis,except for its citadel, and Ardys might have been killed in this attack.[73]Ardys's son and successor,Sadyattes,might possibly also have been killed in another Cimmerian attack on Lydia.[73]Soon after 635 BC, with Assyrian approval[74]the Scythians under Madyes entered Anatolia. In alliance with Sadyattes's son, the Lydian kingAlyattes,[75][76]Madyes expelled the Treres from Asia Minor and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia[77]until they were themselves expelled by the Medes from Western Asia in the 600s BC.[72]

Achaemenid Thrace

[edit]

In the 6th century BC thePersianAchaemenid Empireconquered Thrace, starting in 513 BC, when the Achaemenid kingDarius Iamassed an army and marched from Achaemenid-ruled Anatolia into Thrace, and from there he crossed theArteskosriver and then proceeded through the valley-route of theHebrosriver. This was an act of conquest by Darius I, who sought to create a new satrapy in the Balkans, and had during his march sent emissaries to the Thracians found on the path of his army as well as to the many other Thracian tribes over a wide area. All these peoples of Thrace, including the Odrysae, submitted to the Achaemenid king until his army reached the territory of Thracian tribe of theGetaewho lived just south of the Danube river and who in vain attempted to resist the Achaemenid conquest. After the resistance of the Getae was defeated and they were forced to provide the Achaemenid army with soldiers, all the Thracian tribes between theAegean Seaand theDanuberiver had been subjected by the Achaemenid Empire. Once Darius had reached the Danube, he crossed the river andcampaigned against the Scythians,after which he returned to Anatolia through Thrace and left a large army in Europe under the command of his generalMegabazus.[78]

Following Darius I's orders to create a new satrapy for the Achaemenid Empire in the Balkans, Megabazus forced the Greek cities who had refused to submit to the Achaemenid Empire, starting withPerinthus,after which led military campaigns throughout Thrace to impose Achaemenid rule over every city and tribe in the area. With the help of Thracian guides, Megabazus was able to conquerPaeoniaup to but not including the area of Lake Prasias, and he gave the lands of thePaeoniansinhabiting these regions up to the Lake Prasias to Thracians loyal to the Achaemenid Empire. The last endeavours of Megabazus included his the conquest of the area between theStrymonandAxiusrivers, and at the end of his campaign, the king ofMacedonia,Amyntas I,accepted to become a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. Within the satrapy itself, the Achaemenid king Darius granted to the tyrantHistiaeusofMiletusthe district ofMyrcinuson the Strymon's east bank until Megabazus persuaded him to recall Histiaeus after he returned to Asia Minor, after which the Thracian tribe of theEdoniretook control of Myrcinus.[78]The new satrapy, once created, was namedSkudra(𐎿𐎤𐎢𐎭𐎼), derived from Scythian the nameSkuδa,which was the self-designation of theScythianswho inhabited the northern parts of the satrapy.[79]Once Megabazus had returned to Asia Minor, he was succeeded inSkudraby a governor whose name is unknown, and Darius appointed the generalOtanesto oversee the administrative division of the Hellespont, which extended on both sides of the sea and included theBosporus,thePropontis,and theHellespontproper and its approaches. Otanes then proceeded to captureByzantium,Chalcedon,Antandrus,Lamponeia,Imbros,andLemnosfor the Achaemenid Empire.[78]

The area included within the satrapy ofSkudraincluded both the Aegean coast of Thrace, as well as its Pontic coast till the Danube. In the interior, the Western border of the satrapy consisted of theAxiusriver and theBelasica-Pirin-Rilamountain ranges till the site of modern-dayKostenets.The importance of this satrapy rested in that it contained theHebrosriver, where a route in the river valley connected the permanent Persian settlement ofDoriscuswith the Aegean coast, as well as with the port-cities ofApollonia,MesembriaandOdessoson the Black Sea, and with thecentral Thracian plain,which gave this region an important strategic value. Persian sources describe the province as being populated by three groups: theSaka Paradraya( "Saka beyond the sea", the Persian term for allScythianpeoples to the north of theCaspianandBlackSeas[80][81]); theSkudrathemselves (most likely the Thracian tribes), andYauna Takabara.The latter term, which translates as "Ionianswith shield-like hats ", is believed to refer toMacedonians.The three ethnicities (Saka, Macedonian, Thracian) enrolled in theAchaemenid army,as shown in the Imperial tomb reliefs ofNaqsh-e Rostam,and participated in theSecond Persian invasion of Greeceon the Achaemenid side.[82]

When Achaemenid control over its European possessions collapsed once theIonian Revoltstarted, the Thracians did not help the Greek rebels, and they instead saw Achaemenid rule as more favourable because the latter had treated the Thracians with favour and even given them more land, and also because they realised that Achaemenid rule was a bulwark against Greek expansion and Scythian attacks. During the revolt, Aristagoras of Miletus captured Myrcinus from the Edones and died trying to attack another Thracian city.[78]

Once the Ionian Revolt had been fully quelled, the Achaemenid generalMardoniuscrossed the Hellespont with a large fleet and army, re-subjugated Thrace without any effort and made Macedonia full part of the satrapy ofSkudra.Mardonius was however attacked at night by theBrygesin the area ofLake Doiranand modern-dayValandovo,but he was able to defeat and submit them as well. Herodotus's list of tribes who provided the Achaemenid army with soldiers included Thracians from both the coast and from the central Thracian plain, attesting that Mardonius's campaign had reconquered all the Thracian areas which were under Achaemenid rule before the Ionian Revolt.[78]

When the Greeksdefeatedasecond invasion attemptby the Persian Empire in 479 BC, they started attacking the satrapy ofSkudra,which was resisted by both the Thracians and the Persian forces. The Thracians kept on sending supplies to the governor ofEionwhen the Greeks besieged it. When the city fell to the Greeks in 475 BC,Cimongave its land toAthensfor colonisation. Although Athens was now in control of the Aegean Sea and the Hellespont following the defeat of the Persian invasion, the Persians were still able to control the southern coast of Thrace from a base in central Thrace and with the support of the Thracians. Thanks to the Thracians co-operating with the Persians by sending supplies and military reinforcements down the Hebrus river route, Achaemenid authority in central Thrace lasted until around 465 BC, and the governorMascamesmanaged to resist many Greek attacks in Doriscus until then.[78]

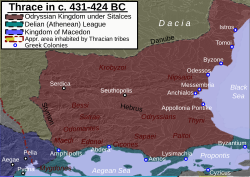

Around this time,Teres I,the king of the Odrysae tribe, in whose territory the Hebrus flowed, was starting to organise the rise of his kingdom into a powerful state. With the end of Achaemenid power in the Balkans, the ThracianOdrysian kingdom,theKingdom of Macedonia,and theAthenian thalassocracyfilled the ensuing power vacuum and formed their own spheres of influence in the area.[78]

Odrysian Kingdom

[edit]

The Odrysian Kingdom was a state union of over 40 Thracian tribes[83]and 22 kingdoms[84]that existed between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD. It consisted mainly of present-dayBulgaria,spreading to parts of SoutheasternRomania(Northern Dobruja), parts of NorthernGreeceand parts of modern-dayEuropean Turkey.[citation needed]

By the 5th century BC, the Thracian population was large enough thatHerodotuscalled them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after theIndians), and potentially the most powerful, if not for their lack of unity.[85]The Thracians in classical times were broken up into a large number of groups and tribes, though a number of powerful Thracian states were organized, the most important being theOdrysian kingdomof Thrace, and also the short livedDacian kingdomofBurebista.Thepeltastisa type of soldier of this period that originated in Thrace.[86]

At this time, a subculture ofcelibateasceticscalled the "ctistae"lived in Thrace, where they served as philosophers, priests and prophets. They were held in a place of honor by the Thracians, with their lives being dedicated to the gods.[87]

Macedonian Thrace

[edit]During this period, contacts between the Thracians andClassical Greeceintensified.[citation needed]

After the Persians withdrew from Europe and before the expansion of the Kingdom of Macedon, Thrace was divided into three regions (east, central, and west). A notable ruler of the East Thracians wasCersobleptes,who attempted to expand his authority over many of the Thracian tribes. He was eventually defeated by theMacedonians.[citation needed]

The Thracians were typically not city-builders[88][89]and their onlypoliswasSeuthopolis.[90][91]

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace byPhilip II of Macedonin the 4th century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such asLysimachusof theDiadochi.[citation needed]

In 336 BC,Alexander the Greatbegan recruiting thraciancavalryandjavelin menin his army, who accompnied him on his continuousconquestto expand the borders of theMacedonian Empire.[92]The strength of the thracian cavalry quickly grew from 150 men, to 1000 men by the time Alexander advanced intoEgypt,and numbered 1600 when he reached the persian city ofSusa.The thracian infantry was under the command of the Odrysian princeSitalces IIwho led them in the siege ofTelmissusand in the battles ofIssusandGaugamela.[92]

In 279 BC,Celtic Gaulsadvanced intoMacedonia,southern Greece andThrace.They were soon forced out of Macedonia and southern Greece, but theyremained in Thraceuntil the end of the 3rd century BC. From Thrace, three Celtic tribes advanced intoAnatoliaand established the kingdom ofGalatia.[citation needed]

In western parts ofMoesia,Celts (Scordisci) and Thracians lived alongside each other, as evident from the archaeological findings of pits and treasures, spanning from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century BC.[93]

Greek raids to enslave Thracians

[edit]Slave raidswere a specific form ofbanditrythat was the primary method employed by theancient Greeksfor gathering slaves. In regions such asThraceand the easternAegean,natives, or "barbarians",captured in these raids were the main source ofslaves,rather thanprisoners of war.As described byXenophon,andMenanderinAspis,after the slaves were captured in raids, their actual enslavement took place when they were resold throughslave-dealerstoAtheniansand otherslaveownersthroughoutGreece.The fragmentary list of slaves confiscated from the property of the mutilators of theHermaimentions 32 slaves whose origins have been ascertained: 13 came fromThrace,7 fromCaria,and the others came fromCappadocia,Scythia,Phrygia,Lydia,Syria,Ilyria,Macedon,andPeloponnese.The names given to slaves in thecomediesoften had a geographical link, thus Thratta, used byAristophanesinThe Wasps,The Acharnians,andPeace,simply meant a Thracian woman. Theethnicityof a slave was a significant criterion for major purchasers: Ancient practice was to avoid a concentration of too many slaves of the same ethnic origin in the same place, in order to limit the risk ofrevolt.

Roman Thrace

[edit]

During theMacedonian Wars,conflict between Rome and Thrace was unavoidable. The rulers of Macedonia were weak, and Thracian tribal authority resurged. But after theBattle of Pydnain 168 BC, Roman authority over Macedonia seemed inevitable, and the governance of Thrace passed to Rome.[citation needed]

Initially, Thracians and Macedonians revolted against Roman rule. For example, the revolt ofAndriscus,in 149 BC, drew the bulk of its support from Thrace. Incursions by local tribes into Macedonia continued for many years, though a few tribes, such as the Deneletae and the Bessi, willingly allied withRome.[citation needed]

After theThird Macedonian War,Thrace acknowledged Roman authority. Theclient state of Thraciacomprised several tribes.[citation needed]

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. TheSapaeitribe came to the forefront initially under the rule ofRhascuporis.He was known to have granted assistance to bothPompeyandCaesar,and later supported theRepublicanarmies againstMark AntonyandOctavianin the final days of the Republic.[citation needed]

The heirs of Rhascuporis became as deeply enmeshed in political scandal and murder as were their Roman masters. A series of royal assassinations altered the ruling landscape for several years in the early Roman imperial period. Various factions took control with the support of the Roman Emperor. The turmoil would eventually end with one final assassination.[citation needed]

AfterRhoemetalces IIIof the Thracian Kingdom ofSapeswas murdered in AD 46 by his wife, Thracia was incorporated as an official Roman province to be governed byProcurators,and laterPraetorian prefects.The central governing authority of Rome was inPerinthus,but regions within the province were under the command of military subordinates to the governor. The lack of large urban centers made Thracia a difficult place to manage, but eventually the province flourished under Roman rule. However, Romanization was not attempted in the province of Thracia. TheBalkan Sprachbunddoes not support Hellenization.[citation needed]

Roman authority in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed inMoesia.The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and distance from Roman authority, certainly inspired local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migratingGermanic tribes.The reign ofJustiniansaw the construction of over 100legionaryfortresses to supplement the defense.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]

The ancient languages of these people and their cultural influence were highly reduced due to the repeated invasions of the Balkans byRomans,Celts,Huns,Goths,Scythians,SarmatiansandSlavs,accompanied by,hellenization,romanizationand laterslavicisation.However, the Thracians as a group only disappeared in theEarly Middle Ages.[94]Towards the end of the 4th century,Nicetasthe Bishop ofRemesianabrought the gospel to "those mountain wolves", theBessi.[95]Reportedly his mission was successful, and the worship of Dionysus and other Thracian gods was eventually replaced by Christianity.

In 570, Antoninus Placentius said that in the valleys ofMount Sinaithere was a monastery in which the monks spoke Greek, Latin, Syriac, Egyptian and Bessian. The origin of the monasteries is explained in a medievalhagiographywritten bySimeon Metaphrastes,in Vita Sancti Theodosii Coenobiarchae in which he wrote thatTheodosius the Cenobiarchfounded on the shore of theDead Seaa monastery with four churches, in each being spoken a different language, among which Bessian was found. The place where the monasteries were founded was called "Cutila", which may be a Thracian name.[96]

The further fate of the Thracians is a matter of dispute. German historian Gottfried Schramm speculated that theAlbaniansderived from the Christianized Thracian tribeBessi,after their remnants were allegedly pushed bySlavsandBulgarsduring the 9th century westwards into modern dayAlbania.[95]However, archaeologically, there is absolutely no evidence of a 9th-century migration of any population, such as the Bessi, fromwestern Bulgariato Albania.[97]Also from a linguistic point of view it emerges that the Thracian-Bessian hypothesis of the origin of Albanian should be rejected, since only very little comparative linguistic material is available (the Thracian is attested only marginally, while the Bessian is completely unknown), but at the same time the individual phonetic history ofAlbanianand Thracian clearly indicates a very different sound development that cannot be considered as the result of one language. Furthermore, the Christian vocabulary of Albanian is mainlyLatin,which speaks against the construct of a "Thracian-Bessian church language".[98]Most probably the Thracians were assimilated into the Roman and later in the Byzantine society and became part of the ancestral groups of the modern Southeastern Europeans.[99]

Oddly the last mention of Thracians, in the 6th century, coincides with the first mention ofSlavs,when the Slavic tribes inhabited large territories of Central and Eastern Europe.[100]After the 6th century Thracians that weren't already assimilated in theByzantine Empire,were incorporated in the slavic speakingBulgarian Empire.[101]

Bulgarian Thrace

Slavic tribeshad mingled with the Thracian population, prior to the formation of theBulgarian state.[101]Under the leadership ofAsparuh,in 680 AD the Thracians,BulgarsandSlavsreadily united to establish theFirst Bulgarian Empire.[102][103]These three ethnic groups mingled to produce theBulgarianpeople.[104]TheByzantine Empire,retained control overThraceuntil the 7th century when the northern half of the entire region was claimed by theFirst Bulgarian Empireand the remainder was reorganized in theThracian theme.

Legacy

[edit]A recent Bulgarian study on the heritage of Thracian mounds in Bulgaria claims historical, cultural and ethnic links between Thracians andBulgarians.[105][104]Genetic studies on modernBulgariansshow that approximately 55% of Bulgarian autosomal genetic legacy is of Paleo-Balkan and Mediterranean origin which can be attributed to Thracians and other indigenousBalkanpopulations predatingSlavsandBulgars.[106][107][108][109]

Greek Thrace

Turkish Thrace

Culture

[edit]

Language

[edit]The records of Thracian writing are very scarce. There are only four inscriptions that have been discovered. One of them is a gold ring unearthed in the village ofEzerovo,Bulgaria. The thracian inscription is written using the Greek script and consists of 8 lines. Attempts to decipher the inscription have proven inconclusive.[110]

Religion

[edit]

One notable cult that existed inThrace,Moesia,Phrygiaand the lands of theDaciansand theGetae(Scythia Minor,nowDobrudja) was that of the "Thracian horseman",also known asSabaziosor "ThracianHeros"known by aThracianname as HerosKarabazmos,a god of theunderworld,who was usually depicted on funeral statues as a horseman slaying a beast with a spear.[111][112][113]Getaeand Dacians potentially had a monotheistic religion based on the god Zalmoxis, though this is heavily debated in the anthropological community.[114]The supreme Balkan thunder godPerkonwas part of the Thracian pantheon, although cults ofOrpheusandZalmoxislikely overshadowed his.[citation needed]

The Thracians are considered the first to worship the god of wine calledDionysusin Greek orZagreusin Thracian.[115]Later this cult reached Ancient Greece.[116][117]Some consider Thrace as the motherland of wine culture.[118]The works ofHomer,Herodotusand other historians of Ancient Greece also refer to theancient Thracians' love for winemaking and consumption, also related to religion[119]as early as 6000 years ago.[120]

Marriage

[edit]The male Thracians were polygamous.Menanderputs it: "All Thracians, especially us and theGetae,are not much abstaining, because no one takes less than ten, eleven, twelve wives, some even more. If one dies and has only four or five wives he is called ill-fated, unhappy and unmarried."[121]According to Herodotus virginity among women was not valued, and unmarried Thracian women could have sex with any man they wished to.[121] There were men perceived as holy Thracians, who lived without women and were called "ktisti".[121]In myth,Orpheusrebuked the sexual advances of theBistoneswomen after the death ofEurydice,and was killed for not engaging in the activities promoted by the followers ofDionysus.

Warfare

[edit]

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins.[122]Thracianpeltastshad a notable influence in Ancient Greece.[123]

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by AncientGreekand Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.[citation needed]

Genetics

[edit]A genetic study published inScientific Reportsin 2019 examined themtDNAof 25 Thracian remains inBulgariafrom the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. They were found to harbor a mixture of ancestry fromWestern Steppe Herders(WSHs) andEarly European Farmers(EEFs), supporting the idea that Southeast Europe was the link between Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean.[3]

A Bulgarian study from 2013 claims genetic similarity between Thracians (8-6 century BC), medieval Bulgarians (8–10 century AD), and modern Bulgarians, highlighting highest resemblance between them and Romanians, Northern Italians and Northern Greeks.[124]

Examinations of Iron Age and ancient Thracian remains in Bulgaria were found to mainly carry the Y-DNA haplogroupE-V13.[125]The tested samples were further specifically listed as: E-BY3880 x 3, E-L618 x 2, E-M78 x 2, R-Z93, E-CTS1273, E-BY14160.[126] Six of the samples were predicted for having brown eyes while two for having blue eyes, while majority of the samples were predicted for an intermediate skin color and hair color prediction ranged from majority brown on detailed, to light and dark.[127]

Notable people

[edit]

This is a list of historically important personalities being entirely or partly of Thracian and Dacian ancestry:

- Orpheus,mythological figure considered chief among poets and musicians; king of the Thracian tribe ofCicones

- Rhesus of Thrace,mythical king ofThraceinThe Iliadwho fought on the side ofTrojans

- Eumolpus,legendary king ofThracedescribed as having come toAtticaeither as a bard, a warrior, or a priest ofDemeterandDionysus

- Tereus,mythologicalThracianking,[128][129]the son ofAresand the naiadBistonis

- Spartacus,Thracian gladiator who led a large slave uprising in Southern Italy in 73–71 BC and defeated several Roman legions in what is known as theThird Servile War

- Amadocus,Thracian King, theAmadok Pointwas named after him

- Teres I,Thracian King who united many tribes of Thrace under the banner of theOdrysianstate

- Seuthes I

- Seuthes II

- Seuthes III

- Cotys I

- Sitalces,King of theOdrysianstate; an ally of theAtheniansduring thePeloponnesian War

- Burebista,King ofDacia

- Decebalus,King of Dacia

- Maximinus Thrax,Roman Emperor from 235 to 238.[130]

- Aureolus,Roman military commander

- Galerius,Roman Emperor from 305 to 311; born to a Thracian father and Dacian mother

- Constantine the Great,Roman Emperor from 306 to 337; born to Thracian father[131][132]fromNaissusand Thracian (Bithynian) mother inNaissus

- Licinius,Roman Emperor from 308 to 324

- Maximinus Daiaor Maximinus Daza, Roman Emperor from 308 to 313

- Justin I,Eastern Roman Emperor and founder of theJustinian dynasty

- Justinian the Great,Eastern Roman Emperor; either Illyrian or Thracian, born inDardania

- Belisarius,Eastern Roman general of reputed Illyrian, Greek or Thracian origin

- Marcian,Eastern Roman Emperor from 450 to 457; either Illyrian or Thracian

- Leo I the Thracian,Eastern Roman Emperor from 457 to 474

- Bouzesor Buzes, Eastern Roman general active during the reign of Justinian the Great (r. 527–565)

- Coutzesor Cutzes, general of the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Emperor Justinian I

Thracology

[edit]Archaeology

[edit]The branch of science that studies the ancient Thracians and Thrace is calledThracology.Archaeological research on theThracian culturestarted in the 20th century, especially afterWorld War II,mainly in southernBulgaria.As a result of intensive excavations in the 1960s and 1970s a number of Thracian tombs and sanctuaries were discovered. Most significant among them are: theGetic burial complexand theTomb of Sveshtari,theValley of the Thracian Rulersand theTomb of Kazanlak,Tatul,Seuthopolis,Perperikon,Tomb of Aleksandrovoin Bulgaria,Sarmizegetusain Romania and others.[citation needed] Also a large number of elaborately crafted gold and silver treasure sets from the 5th and 4th century BC were unearthed. In the following decades, those were exhibited in museums around the world, thus calling attention to ancient Thracian culture. Since the year 2000, Bulgarian archaeologistGeorgi Kitovhas made discoveries in Central Bulgaria, in an area now known as "The Valley of the Thracian Kings". The residence of theOdrysian kingswas found inStaroselin theSredna Goramountains.[133][134]A 1922 Bulgarian study claimed that there were at least 6,269necropolises[clarification needed]in Bulgaria.[135]

Multidisciplinary Studies

[edit]The dominant stance of history and archaeology as the two main disciplines dealing with the Thracians as a subject of research has been succeeded by a clear shift towards new multidisciplinary and more inclusive scientific perspectives. An example of this new trend was the large-scale multidisciplinary project "Thracians – Genesis and Development of the Ethnos, Cultural Identities, Civilization Relations and Heritage of the Antiquity", launched in 2016 in Bulgaria. The project was the first comprehensive study of the Thracian heritage including 72 scholars from 18 institutes of the Bulgarian Academy of Science, as well as researchers from Canada, Italy, Germany, Japan and Switzerland. The project studied 13 scientific themes among which: formation of the Thracian ethnos, outlining of its ethno-cultural territory, continuity of the gene pool and related DNA studies, architectural, botanical, microbiological, astronomical, acoustic and linguistic aspects, mining and ceramics technologies, food and drink customs, that resulted in an extensively illustrated book including 33 scientific articles.[136]

Gallery

[edit]-

Thracian tribes and heroes

-

Map of the territory of Philip II of Macedon

-

Kingdom of Lysimachus and the Diadochi

-

Map of the Diocese of Thrace (Dioecesis Thraciae)c. 400AD

-

Golden Dacian helmet of Cotofenesti, in Romania

-

Gold coins that have been minted by the Dacians, with the legend ΚΟΣΩΝ

-

A gold Thracian treasure fromPanagyurishte,Bulgaria

-

Thracian tomb Shushmanets,built in 4th century BC

-

The interior of theSveshtari tomb

-

Interior ofTomb of Seuthes III

-

Bronze head of Seuthes III

-

Thracian Cavalry

-

Thracian Horseman Relief

-

Coin of Seuthes III

-

TheThracian Horsemanon the modernBulgarian currency

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abWebber 2001,p. 3. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, Romania, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, divided among up to 40 tribes."

- ^Modi et al. 2019."One of the best documented Indo-European civilizations that inhabited Romania, Bulgaria is the Thracians..."

- ^abModi et al. 2019.

- ^abcNature(2019) Ancient human mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Bulgaria: new insights into the genetic history of Thracians

- ^Popov, D. The Greek intellectuals and the Thracian world.Iztok - Zapad2, 13–203 (2013).

- ^Fol, A. The Thracian orfeism.Sofia,145–244 (1986).

- ^Fol, A. The History of Bulgarian lands in antiquity.Tangra TanNakRa,11–300 (2008).

- ^Chichikova, M. The Thracian city - Terra Antiqua Balcanica.GSUIF C, 85–93 (1985).

- ^Danov, H. G. Thracian a source of knowledge.Veliko Tarnovo,50–58 (1998).

- ^Raicheva, L. Thracians and Orpheism.IK Ogledalo,5–59 (2014).

- ^Fol, A., Georgiev, V. & Danov, H. The History of Bulgaria. Primarily - communal and slavery.Thracians. BAS, Sofia1, 110–274 (1979).

- ^Mihailov, G. The Thracians.New Bulgarian University2, 1–491 (2015).

- ^Fragment B16 within "the well-known fragments" B14-B16,"Xenophanes", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Accessed: February 20, 2023).

- ^"Thrace".Britannica.Archived fromthe originalon 18 April 2021.Retrieved18 April2021.

- ^Vlassopoulos, Kostas (2013).Greeks and Barbarians.Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–125.ISBN978-1-107-24426-9.

- ^Shchukin, M. B. (1989).Rome and the Barbarians in Central and Eastern Europe: 1st Century B.C.-1st Century A.D.B.A.R. p. 79.ISBN978-0-86054-690-0.

- ^Hind, J. G. F. "Archaeology of the Greeks and Barbarian Peoples around the Black Sea (1982-1992)."Archaeological Reports,no. 39, 1992, pp. 82–112.JSTOR

- ^Boardman, John (1970).The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 1.Cambridge University Press. p. 836.ISBN0-521-85073-8.

- ^Navicula Bacchi – Θρηικίη(Accessed: October 13, 2008).

- ^Garašanin 1982,p. 597. "We have no way of knowing what the Thracians called themselves and if indeed they had a common name... Thus the name of Thracians and that of their country were given by the Greeks to a group of Hellenic tribes occupying the territory...".

- ^Lemprière and Wright,[full citation needed]p. 358. "Mars was father of Cupid, Anteros, and Harmonia, by the goddess Venus. He had Ascalaphus and Ialmenus by Astyoche; Alcippe by Agraulos; Molus, Pylus, Euenus, and oThestius, by Demonice the daughter of Agenor. Besides these, he was the reputed father of Romulus, Oenomaus, Bythis, Thrax, Diomedes of Thrace, &c."

- ^Euripides,Alcestisp. 95. "[Line] 58. 'Thrace's golden shield' – One of the names of Ares was Thrax, he being the Patron of Thrace. His golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia there. Like the other Thracian bucklers, it was of the shape of a half-moon ('Pelta'). His 'festival of Mars Gradivus' was kept annually by the Latins in the month of March, when this sort of shield was displayed."

- ^abcSchütz, István (2006).Fehér foltok a Balkánon[White spots in the Balkans](PDF).Balassi Kiadó. p. 57.

- ^Hoddinott 1981,p. 27.

- ^Casson 1977,p. 3.

- ^abBritannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Thrace".Encyclopedia Britannica,15 Mar. 2024

- ^The catalogue ofKimbell Art Museum's 1998 exhibitionAncient Gold: The Wealth of the Thraciansindicates a historical extent of Thracian settlement including most ofUkraine,all ofHungaryand parts ofSlovakia.(Kimbell Art – Exhibitions)

- ^Stephanus Of Byzantium - Ethnica,Theta 316.9

- ^Billerbeck, Margarethe (2010).Stephanus von Byzanz: Stephani Byzantii Ethnica / Delta - Iota(in German). pp. Theta.ISBN978-3111738505.

- ^abThucydides.History of the Peloponnesian War.Vol. 2.29.

- ^Fol et al. 1998,p. 32-71

- ^Eliade, Mircea; Culianu, Ioan Petru; Wiesner, Hillary S (1993).Dicţionar al religiilor[Dictionary of religions] (in Romanian). Humanitas. p. 267.ISBN978-973-28-0394-3.OCLC489886127.

- ^Schütz, István (2006).Fehér foltok a Balkánon[White spots in the Balkans](PDF).Balassi Kiadó. p. 58.

- ^Jones, Lindsay (2005).Encyclopedia of religion(13 ed.).Macmillan Reference USA.ISBN9780028659824.Archived from the original on April 5, 2023.

- ^Webber 2001,p. 3.

- ^Head, Duncan (1982).Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars, 359 BC to 146 BC: Organisation, Tactics, Dress and Weapons.Wargames Research Group. p. 51.ISBN978-0-904417-26-5.

- ^abcdeVictor Duruy(1886).History of Rome And of the Roman People, from Its Origin to the Invasion of the Barbarians · Volume 4, Part 1.Dana, Estes & Company. pp. 3–4.

- ^Plato.Republic:"Take the quality of passion or spirit;--it would be ridiculous to imagine that this quality, when found in States, is not derived from the individuals who are supposed to possess it, e.g. the Thracians, Scythians, and in general the northern nations;"

- ^Plato.Laws:"Are we to follow the custom of the Scythians, and Persians, and Carthaginians, and Celts, and Iberians, and Thracians, who are all warlike nations, or that of your countrymen, for they, as you say, altogether abstain?"

- ^Polybius.Histories,27.12.

- ^Tacitus.Annals:"In the Consulship of Lentulus Getulicus and Caius Calvisius, the triumphal ensigns were decreed to Poppeus Sabinus for having routed some clans of Thracians, who living wildly on the high mountains, acted thence with the more outrage and contumacy. The ground of their late commotion, not to mention the savage genius of the people, was their scorn and impatience, to have recruits raised amongst them, and all their stoutest men enlisted in our armies; accustomed as they were not even to obey their native kings further than their own humour, nor to aid them with forces but under captains of their own choosing, nor to fight against any enemy but their own borderers."

- ^Tonkova, Milenka (2010). "On human sacrifice in Thrace (on archaeological evidence)". In Cândea, Ionel; Sîrbu, Valeriu (eds.).Tracii şi vecinii lor în antichitate.Ed. Istros a Muzeului Brăilei. pp. 503–514.ISBN978-973-1871-58-5.OCLC844101517.

- ^Polyaenus.Strategems.Book 7,The Thracians.

- ^Strabo.History,9.401 (9.2.4).

- ^Polyaenus.Strategems.Book 7,Clearchus.

- ^Webber 2001,p. 6.

- ^abArchibald, Zofia (1998).The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace: Orpheus Unmasked.Clarendon Press. p. 100.ISBN978-0-19-815047-3.OCLC1000881553.

- ^abWebber 2001,p. 7.

- ^Friedrich Max Müller(1866).Lectures on the Science of Language Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in... 1861 [and]... 1863: [first And] Second Series · Volume 1.Longmans Green. p. 111.

- ^Herodotus (trans. G.C. Macaulay).The History of Herodotus(Volume II). "Of the other Thracians the custom is to sell their children to be carried away out of the country; and over their maidens they do not keep watch, but allow them to have commerce with whatever men they please, but over their wives they keep very great watch."

- ^Enos, R. L. (1976). Rhetorical intent in ancient historiography: Herodotus and the battle of marathon.Communication Quarterly,24(1), 24–31.

- ^Evans, J. A. S. "Father of History or Father of Lies; The Reputation of Herodotus."The Classical Journal,vol. 64,no. 1, 1968, pp. 11–17.JSTOR

- ^Hu, Rollin (February 11, 2016)."Herodotus' Histories and its reliability".The Johns Hopkins News-Letter.RetrievedMarch 13,2019.

- ^Klass, Rosanne (June 26, 1977)."Thracian Clues To Our 'Barbarian' Heritage".The New York Times.RetrievedMarch 13,2019.

- ^Webber 2001,p. 17.

- ^Reilly, Kevin; Kaufman, Stephen; Bodino, Angela (2003).Racism: A Global Reader.M.E. Sharpe. pp. 121–122.ISBN978-0-7656-1060-7.

- ^abCohen, Beth, ed. (2000).Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art.BRILL. p. 371.ISBN978-90-04-11712-9.

- ^Diels, B16,Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker,1903, pp.38–58 (Xenophanes fr. B16, Diels-Kranz, Kirk/Raven no. 171 [= Clem. Alex. Strom. Vii.4]

- ^Ode 18, Dithyramb 4, verse 51, quoted inBacchylides: a selection By Bacchylides,Herwig Maehler, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 191.

- ^Hecataeus mentions a Thracian tribe called theXanthoi(Nenci 1954: fragment 191 ) apparently named for their fair (red) hair (Helm 1988: 145), quoted inIndo-European origins: the anthropological evidence Institute for the Study of Man,John v. day, 2001 p. 39.

- ^De Temp. II. 5

- ^Clem. Alex. Strom. Vii.4

- ^Matheseos Libri Octo, II. 1,quoted inAncient Astrology Theory and Practice,Jean Rhys Bram 2005, pp. 14, 29.

- ^Beth Cohen (ed.)Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art.Leiden, 2000.[page needed]

- ^Poulianos, Aris N., 1961, The Origin of the Greeks, Ph.D. thesis, University of Moscow, supervised by F.G.Debets

- ^Homer, Illiad II 480

- ^Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924: at2.581

- ^Altschuler, Eric Lewin; Calude, Andreea S.; Meade, Andrew; Pagel, Mark (May 2013)."Linguistic evidence supports date for Homeric epics".BioEssays.35(5): 417–420.doi:10.1002/bies.201200165.PMC3654165.PMID23417708.

- ^abCormack & Wilkes 2015.

- ^Marinov 2015,p. 11.

- ^Diakonoff 1985,p. 94-55.

- ^abSpalinger, Anthony J. (1978)."The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications".Journal of the American Oriental Society.98(4): 400–409.doi:10.2307/599752.JSTOR599752.Retrieved25 October2021.

- ^abDale, Alexander (2015)."WALWET and KUKALIM: Lydian coin legends, dynastic succession, and the chronology of Mermnad kings".Kadmos.54:151–166.doi:10.1515/kadmos-2015-0008.S2CID165043567.Retrieved10 November2021.

- ^Grousset, René(1970).The Empire of the Steppes.Rutgers University Press. pp.9.ISBN0-8135-1304-9.

A Scythian army, acting in conformity with Assyrian policy, entered Pontis to crush the last of the Cimmerians

- ^Diakonoff 1985,p. 126.

- ^Ivantchik, Askold(1993).Les Cimmériens au Proche-Orient[The Cimmerians in the Near East] (in French).Fribourg,Switzerland;Göttingen,Germany: Editions Universitaires (Switzerland);Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht(Germany). pp. 95–125.ISBN978-3-7278-0876-0.

- ^Phillips, E. D. (1972)."The Scythian Domination in Western Asia: Its Record in History, Scripture and Archaeology".World Archaeology.4(2): 129–138.doi:10.1080/00438243.1972.9979527.JSTOR123971.Retrieved5 November2021.

- ^abcdefgHammond, N. G. L.(1980)."The Extent of Persian Occupation in Thrace".Chiron: Mitteilungen der Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts.10:53–61.Retrieved20 January2022.

- ^Szemerényi, Oswald(1980).Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian – Skudra – Sogdian – Saka(PDF).Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.pp. 23–25.ISBN978-3-7001-0367-7.

- ^J. M. Cook (6 June 1985)."The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire".In Ilya Gershevitch (ed.).The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2.Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255.ISBN978-0-521-20091-2.

- ^M. A. Dandamayev (1999).History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250.UNESCO. pp. 44–46.ISBN978-81-208-1540-7.

- ^Hammond, N. G. L.;Fol, Alexander."Persia in Europe, apart from Greece".The Cambridge Ancient History.Vol. 4.Cambridge University Press.pp. 246–253.ISBN978-0-521-22804-6.

- ^Thrace.The History Files.

- ^"Interview: Capital of largest Thracian kingdom discovered in Bulgaria".xinhuanet.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-02-04.Retrieved2016-05-26.

- ^Herodotus.Histories,Book V.

- ^Williams, Mary Frances (2004)."Philopoemen's Special Forces: Peltasts and a New Kind of Greek Light-Armed Warfare (Livy 35.27)".Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte.53(3): 257–277.JSTOR4436729.

- ^Strabo, Geography VII.3.3

- ^Garašanin 1982,p. 612. "Thrace possessed only fortified areas, and cities such as Cabassus would have been no more than large villages. In general the population lived in villages and hamlets.".

- ^Garašanin 1982,p. 612. "According to Strabo (vii.6.1cf.st.Byz.446.15) the Thracian suffix -bria meant polis but it is an inaccurate translation..

- ^Mogens Herman Hansen.An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation.Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 888. "It was meant to be a polis but there was no reason to think that it was anything other than a native settlement."

- ^Webber 2001.

- ^abAshley, James (2004).The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359-323 B.C.McFarland. pp. 34, 46.ISBN978-0786419180."James+R.+Ashley" &printsec=frontcover Ashley, The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great

- ^"Funerary Practices in Europe, before and after the Roman Conquest"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-18.Retrieved2010-09-21.

- ^Schütz, István (2006).Fehér foltok a Balkánon[White spots in the Balkans](PDF).Balassi Kiadó. p. 60.

- ^abGottfried Schramm: A New Approach to Albanian History 1994[full citation needed][verification needed]

- ^Linguistics Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 8 September 2012.[full citation needed]

- ^Curta, Florin (2020). "Migrations in the Archaeology of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages (Some Comments on the Current State of Research)". In Preiser-Kapeller, Johannes; Reinfandt, Lucian; Stouraitis, Yannis (eds.).Migration Histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone: Aspects of Mobility Between Africa, Asia and Europe, 300-1500 C.E.Studies in Global Migration History. Vol. 13. Brill. pp. 101–140.ISBN978-90-04-42561-3.ISSN1874-6705.p. 105.

- ^Matzinger, Joachim (30 November 2016)."Die albanische Autochthonie hypothese aus der Sicht der Sprachwissenschaft"[Hypotheses on the Albanian origins by the perspective of linguistics](PDF)(in German): 15–16.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^T.N. Pollio (2021) The Art of Medieval Jewelry. An Illustrated History. McFarland,ISBN9781476681757,p. 70.

- ^Origin of The Slavsp.2

- ^abAngelov et al 1981,p. 261

- ^Angelov et al 1981,p. 264

- ^Fine 1991,p. 128

- ^abGarrett Hellenthal et al

- ^Loulanski, Tolina; Loulanski, Vesselin (2017)."Thracian Mounds in Bulgaria: Heritage at Risk".The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice.8(3): 246–277.doi:10.1080/17567505.2017.1359918.

- ^Karachanak, S.; Grugni, V.; Fornarino, S.; Nesheva, D.; Al-Zahery, N.; Battaglia, V.; Carossa, V.; Yordanov, Y.; Torroni, A.; Galabov, A. S.; Toncheva, D.; Semino, O. (2013)."Y-Chromosome Diversity in Modern Bulgarians: New Clues about Their Ancestry".PLOS ONE.8(3): e56779.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856779K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056779.PMC3590186.PMID23483890.

- ^Hellenthal, G.; Busby, G. B.; Band, G.; Wilson, J. F.; Capelli, C.; Falush, D.; Myers, S. (2014)."A genetic atlas of human admixture history".Science.343(6172): 747–751.Bibcode:2014Sci...343..747H.doi:10.1126/science.1243518.PMC4209567.PMID24531965.

- ^Multi-way admixture in Eastern Europe,Genetic atlas of human admixture history (2014)

- ^Underhill, PA; Poznik, GD; Rootsi, S; Järve, M; Lin, AA; Wang, J; Passarelli, B; Kanbar, J; Myres, NM; King, RJ; Di Cristofaro, J; Sahakyan, H; Behar, DM; Kushniarevich, A; Sarac, J; Saric, T; Rudan, P; Pathak, AK; Chaubey, G; Grugni, V; Semino, O; Yepiskoposyan, L; Bahmanimehr, A; Farjadian, S; Balanovsky, O; Khusnutdinova, EK; Herrera, RJ; Chiaroni, J; Bustamante, CD; Quake, SR; Kivisild, T; Villems, R (2015). "European Journal of Human Genetics - Supplementary Information for article: The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a".European Journal of Human Genetics.23(1): 124–131.doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.50.PMC4266736.PMID24667786.

- ^"Golden ring with Thracian inscription. NAIM-Sofia exhibition".National Archaeological Institute with Museum, Sofia.

- ^Lurker, Manfred (1987).Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons.p. 151.

- ^Nicoloff, Assen (1983).Bulgarian Folklore.p. 50.

- ^Isaac, Benjamin H. (1986).The Greek Settlements in Thrace Until the Macedonian Conquest.p. 257.

- ^Eliade, Mircea (1985).De Zalmoxis à Gengis-Khan.p. 35.

- ^Patricia Turner and Charles Russell Coulter.Dictionary of Ancient Deities.Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 152.

- ^McEvilley, Thomas (2002).The Shape of Ancient Thought.New York, NY: Allsworth press. pp. 118–121.ISBN9781581159332.OCLC460134637.

- ^Ancient Greeks West and East.Gocha R. Tsetskhladze. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. 1999. p. 429.ISBN90-04-11190-5.OCLC41320191.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^(https:// codedevino /world-of-wine/the-way-of-wine/ancient-thrace-the-motherland-of-wine-culture)

- ^"Ancient Thrace, the Motherland of Wine Culture | Code de Vino".Retrieved2022-08-15.

- ^Advertorial (2021-11-17)."Who Are the Thracians and Why Wine Was an Integral Part of Their Culture and Tradition 6000 Years Ago?".Wine Industry Advisor.Retrieved2022-08-15.

- ^abcАнгел Гоев.Еротичното в историята Том 2(PDF).pp. 8, 13, 14.ISBN978-954-400-514-6.

- ^Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. 27 June 2016. p. 552.ISBN978-1-61069-020-1.

- ^Best 1969,p.[page needed].

- ^Karachanak et al., 2012.Karachanak, S., V. Carossa, D. Nesheva, A. Olivieri, M. Pala, B. Hooshiar Kashani, V. Grugni, et al. "Bulgarians vs the Other European Populations: A Mitochondrial DNA Perspective." International Journal of Legal Medicine 126 (2012): 497.

- ^The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe- Lazaridis et al

- ^The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe- Lazaridis et al

- ^The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe. Science 377, eabm4247. (PDF / SUPPLEMENT )- ChalcolithicBronzeAge Supplement

- ^Thucydides:History of the Peloponnesian War2:29

- ^Bibliotheca3.14.8

- ^Most likely he was ofThraco-Romanorigin, believed so by Herodian in his writings,(Herodian, 7:1:1-2) and the references to his "Gothic" ancestry might refer to aGetaeorigin (the two populations were often confused by later writers, most notably byJordanesin hisGetica), as suggested by the paragraphs describing how "he was singularly beloved by the Getae, moreover, as if he were one of themselves" and how he spoke "almost pure Thracian".(Historia Augusta,Life of Maximinus,2:5)

- ^Narodni muzej Niš 2015,p. 7.

- ^Papazoglu 1969,p. 64.

- ^"Bulgarian Archaeologists Make Breakthrough in Ancient Thrace Tomb".Novinite.March 11, 2010.RetrievedApril 3,2010.

- ^"Bulgarian Archaeologists Uncover Story of Ancient Thracians' War with Philip II of Macedon".Novinite.June 21, 2011.RetrievedJune 24,2011.

- ^Izvestii︠a︡: Bulletin.Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.1922. p. 104.[title missing]

- ^Bulgarian Academy of Science (BAS).Bulgarian Academy of Science (BAS); General Academic News/ Thursday, 15 February 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Best, Jan G. P. (1969).Thracian Peltasts: And Their Influence on Greek Warfare.Wolters-Noordhoff.

- Cormack, James Maxwell Ross; Wilkes, John (2015). "Thrace".Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics.doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6417.ISBN978-0-19-938113-5.

- Diakonoff, I. M.(1985). "Media". InGershevitch, Ilya(ed.).The Cambridge History of Iran.Vol. 2.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.pp. 94–95.ISBN978-0-521-20091-2.

- Dumitrescu, VL. (1982). "The Prehistory of Romania from the earliest times to 1000 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.).The Cambridge Ancient History.pp. 1–74.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521224963.002.ISBN978-1-139-05428-7.

- Erdem, Zeynep Koçel; Şahin, Reyhan (2023).Thrace through the ages: pottery as evidence for commerce and culture from prehistoric times to the Islamic period.Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Garašanin, M. (1982). "The Early Iron Age in the Central Balkan Area,c.1000–750 B.C. ". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.).The Cambridge Ancient History.pp. 582–618.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521224963.015.ISBN978-1-139-05428-7.

- Howe, Timothy; Reames, Jeanne (2008).Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza.Regina Books.ISBN978-1-930053-56-4.

- Loulanski, Tolina; Loulanski, Vesselin (2017)."Thracian Mounds in Bulgaria: Heritage at Risk".The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice.8(3): 246–277.doi:10.1080/17567505.2017.1359918.S2CID134064117.

- Marazov, Ivan, ed. (1998).Ancient gold: the wealth of the Thracians: treasures from the Republic of Bulgaria.Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Trust for Museum Exhibitions, in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Bulgaria.ISBN978-1-882507-06-1.

- Marinov, Tchavdar (2015). "Ancient Thrace in the Modern Imagination: Ideological Aspects of the Construction of Thracian Studies in Southeast Europe (Romania, Greece, Bulgaria)". In Daskalov, Roumen; Vezenkov, Alexander (eds.).Entangled Histories of the Balkans.pp. 10–117.doi:10.1163/9789004290365_003.ISBN978-90-04-29036-5.

- Best, Jan and De Vries, Nanny.Thracians and Mycenaeans.Boston, MA: E.J. Brill Academic Publishers, 1989.ISBN90-04-08864-4.

- Cardos, G.; Stoian, V.; Miritoiu, N.; Comsa, A.; Kroll, A.; Voss, S.; Rodewald, A. (2004). "Paleo-mtDNA analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian populations from South-East of Romania".Romanian Journal of Legal Medicine.12(4): 239–246.

- Casson, Lionel(Summer 1977). "The Thracians".The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin.35(1): 3–6.doi:10.2307/3258667.JSTOR3258667.

- Hoddinott, Ralph F. (1981).The Thracians.Thames & Hudson.ISBN0-500-02099-X.

- Modi, Alessandra; Nesheva, Desislava; Sarno, Stefania; Vai, Stefania; Karachanak-Yankova, Sena; Luiselli, Donata; Pilli, Elena; Lari, Martina; Vergata, Chiara; Yordanov, Yordan; Dimitrova, Diana; Kalcev, Petar; Staneva, Rada; Antonova, Olga; Hadjidekova, Savina; Galabov, Angel; Toncheva, Draga; Caramelli, David (December 2019)."Ancient human mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Bulgaria: new insights into the genetic history of Thracians".Scientific Reports.9(1): 5412.Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5412M.doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41945-0.PMC6443937.PMID30931994.

- Samsaris, D. (1980).The Hellenization of Thrace during the Hellenic and Roman Antiquity.Thessaloniki (Doctoral thesis in Greek).doi:10.26268/heal.uoi.3216.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Webber, Christopher (2001).The Thracians, 700 BC - AD 46.Osprey Publishing.ISBN978-1-84176-329-3.

- Webber, Christopher (2011).The Gods of Battle, The Thracians at War 1500 BC- 150 AD.Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books.ISBN978-1-84415-835-5.

Further reading

[edit]- The Yurta-Stroyno Archaeological Project. Studies on the Roman Rural Settlement in Thrace.P. Tušlová – B. Weissová – S. Bakardzhiev (eds.). Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts, 2022.ISBN978-80-7671-068-9(print),ISBN978-80-7671-069-6(online: pdf)

- Kaul, Flemming (2011). "The Gundestrup Cauldron: Thracian Art, Celtic Motifs".Études Celtiques.37(1): 81–110.doi:10.3406/ecelt.2011.2326.