Dermatophytosis

| Dermatophytosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ringworm, tinea |

| |

| Ringworm on a human leg | |

| Specialty | Dermatology,Internal Medicine |

| Symptoms | Red, itchy, scaly, circular skin rash[1] |

| Causes | Fungal infection[2] |

| Risk factors | Using public showers, contact sports, excessive sweating, contact with animals,obesity,poor immune function[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms,microbial culture,microscopic examination[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dermatitis,psoriasis,pityriasis rosea,tinea versicolor[6] |

| Prevention | Keep the skin dry, not walking barefoot in public, not sharing personal items[3] |

| Treatment | Antifungal creams(clotrimazole,miconazole)[7] |

| Frequency | 20% of the population[8] |

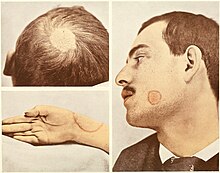

Dermatophytosis,also known astineaandringworm,is afungal infectionof theskin[2](adermatomycosis), that may affect skin, hair, and nails.[1]Typically it results in a red, itchy, scaly, circular rash.[1]Hair loss may occur in the area affected.[1]Symptoms begin four to fourteen days after exposure.[1]Thetypes of dermatophytosisare typically named for area of the body that they affect.[2]Multiple areas can be affected at a given time.[4]

About 40 types of fungus can cause dermatophytosis.[2]They are typically of theTrichophyton,Microsporum,orEpidermophytontype.[2]Risk factors include using public showers, contact sports such aswrestling,excessive sweating, contact with animals,obesity,andpoor immune function.[3][4]Ringworm can spread from other animals or between people.[3]Diagnosis is often based on the appearance and symptoms.[5]It may be confirmed by eitherculturingor looking at a skin scraping under amicroscope.[5]

Prevention is by keeping the skin dry, not walking barefoot in public, and not sharing personal items.[3]Treatment is typically withantifungal creamssuch asclotrimazoleormiconazole.[7]If the scalp is involved, antifungals by mouth such asfluconazolemay be needed.[7]

Dermatophytosis has spread globally, and up to 20% of the world's population may be infected by it at any given time.[8]Infections of the groin are more common in males, while infections of the scalp and body occur equally in both sexes.[4]Infections of the scalp are most common in children while infections of the groin are most common in the elderly.[4]Descriptions of ringworm date back toancient history.[9]

Types

A number of different species of fungus are involved in dermatophytosis.Dermatophytesof the generaTrichophytonandMicrosporumare the most common causative agents. These fungi attack various parts of the body and lead to the conditions listed below. The Latin names are for the conditions (disease patterns), not the agents that cause them. The disease patterns below identify the type of fungus that causes them only in the cases listed:

- Dermatophytosis

- Tinea pedis(athlete's foot): fungal infection of the feet

- Tinea unguium:fungal infection of thefingernailsandtoenails,and the nail bed

- Tinea corporis:fungal infection of the arms, legs, and trunk

- Tinea cruris(jock itch): fungal infection of the groin area

- Tinea manuum:fungal infection of thehandsand palm area

- Tinea capitis:fungal infection of the scalp and hair

- Tinea faciei(face fungus): fungal infection of the face

- Tinea barbae:fungal infestation of facial hair

- Other superficial mycoses (not classic ringworm, since not caused by dermatophytes)

- Tinea versicolor:caused byMalassezia furfur

- Tinea nigra:caused byHortaea werneckii

Signs and symptoms

Infectionson the body may give rise to typical enlarging raised red rings of ringworm. Infection on the skin of the feet may causeathlete's footand in the groin,jock itch.Involvement of the nails is termedonychomycosis.

Animals including dogs and cats can also be affected by ringworm, and the disease can be transmitted between animals and humans, making it azoonotic disease.

Specific signs can be:

- red, scaly, itchy or raised patches

- patches may be redder on outside edges or resemble a ring

- patches that begin to ooze or develop a blister

- bald patches may develop when the scalp is affected

Causes

Fungithrive in moist, warm areas, such aslocker rooms,tanning beds,swimming pools,andskin folds;accordingly, those that cause dermatophytosis may be spread by usingexercise machinesthat have not been disinfected after use, or by sharing towels, clothing, footwear, or hairbrushes.

Diagnosis

Dermatophyte infections can be readily diagnosed based on the history, physical examination, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy.[10]

Prevention

Advice often given includes:

- Avoid sharing clothing, sports equipment, towels, or sheets.

- Wash clothes in hot water withfungicidalsoap after suspected exposure to ringworm.

- Avoid walking barefoot; instead wear appropriate protective shoes in locker rooms and sandals at the beach.[11][12][13]

- Avoid touching pets with bald spots, as they are often carriers of the fungus.

Vaccination

As of 2016,[update]no approved human vaccine exist against dermatophytosis. Forhorses,dogsandcatsthere is available an approved inactivated vaccine calledInsol Dermatophyton(Boehringer Ingelheim) which provides time-limited protection against severaltrichophytonandmicrosporumfungal strains.[14]With cattle, systemic vaccination has achieved effective control of ringworm. Since 1979 a Russian live vaccine (LFT 130) and later on a Czechoslovakian live vaccine against bovine ringworm has been used. In Scandinavian countries vaccination programmes against ringworm are used as apreventive measureto improve the hide quality. In Russia, fur-bearing animals (silver fox, foxes, polar foxes) and rabbits have also been treated with vaccines.[15]

Treatment

Antifungal treatmentsincludetopical agentssuch asmiconazole,terbinafine,clotrimazole,ketoconazole,ortolnaftateapplied twice daily until symptoms resolve — usually within one or two weeks.[16]Topical treatments should then be continued for a further 7 days after resolution of visible symptoms to prevent recurrence.[16][17]The total duration of treatment is therefore generally two weeks,[18][19]but may be as long as three.[20]

In more severe cases or scalp ringworm,systemic treatmentwith oral medications (such asitraconazole,terbinafine,andketoconazole) may be given.[21]

To prevent spreading the infection, lesions should not be touched, and good hygiene maintained with washing of hands and the body.[22]

Misdiagnosis and treatment of ringworm with atopical steroid,a standard treatment of the superficially similarpityriasis rosea,can result intinea incognito,a condition where ringworm fungus grows without typical features, such as a distinctive raised border.[citation needed]

History

Dermatophytosis has been prevalent since before 1906, at which time ringworm was treated with compounds ofmercuryor sometimessulfuroriodine.Hairy areas of skin were considered too difficult to treat, so thescalpwas treated withX-raysand followed up withantifungalmedication.[23]Another treatment from around the same time was application ofAraroba powder.[24]

Terminology

The most common term for the infection, "ringworm", is amisnomer,since the condition is caused byfungiof several differentspeciesand not byparasitic worms.

Other animals

Ringworm caused byTrichophyton verrucosumis a frequent clinical condition incattle.Young animals are more frequently affected. The lesions are located on the head, neck, tail, andperineum.[25]The typical lesion is a round, whitish crust. Multiple lesions may coalesce in "map-like" appearance.

-

Multiple lesions, head

-

Around the eyes and on ears

-

On cheeks: crusted lesion (right)

-

Old lesions, with regrowing hair

-

On neck and withers

-

On perineum

Clinical dermatophytosis is also diagnosed insheep,dogs,cats,andhorses.Causative agents, besidesTrichophyton verrucosum, areT. mentagrophytes,T. equinum,Microsporum gypseum,M. canis,andM. nanum.[26]

Dermatophytosis may also be present in theholotypeof theCretaceouseutriconodontmammalSpinolestes,suggesting aMesozoicorigin for this disease.

Diagnosis

Ringworm in pets may often be asymptomatic, resulting in acarrier conditionwhich infects other pets. In some cases, the disease only appears when the animal develops animmunodeficiencycondition. Circular bare patches on the skin suggest the diagnosis, but no lesion is truly specific to the fungus. Similar patches may result fromallergies,sarcoptic mange,and other conditions. Three species of fungi cause 95% of dermatophytosis in pets:[citation needed]these areMicrosporum canis,Microsporum gypseum,andTrichophyton mentagrophytes.

Veterinarianshave several tests to identify ringworm infection and identify the fungal species that cause it:

Woods test: This is anultraviolet lightwith a magnifying lens. Only 50% ofM. caniswill show up as an apple-green fluorescence on hair shafts, under the UV light. The other fungi do not show. The fluorescent material is not the fungus itself (which does not fluoresce), but rather an excretory product of the fungus which sticks to hairs. Infected skin does not fluoresce.

Microscopic test: The veterinarian takes hairs from around the infected area and places them in a staining solution to view under the microscope. Fungal spores may be viewed directly on hair shafts. This technique identifies a fungal infection in about 40%–70% of the infections, but cannot identify the species of dermatophyte.

Culture test: This is the most effective, but also the most time-consuming, way to determine if ringworm is on a pet. In this test, the veterinarian collects hairs from the pet, or else collects fungal spores from the pet's hair with a toothbrush, or other instrument, and inoculates fungal media for culture. These cultures can be brushed with transparent tape and then read by the veterinarian using a microscope, or can be sent to a pathological lab. The three common types of fungi which commonly cause pet ringworm can be identified by their characteristic spores. These are different-appearingmacroconidiain the two common species ofMicrospora,and typicalmicroconidiainTrichophytoninfections.[26]

Identifying the species of fungi involved in pet infections can be helpful in controlling the source of infection.M. canis,despite its name, occurs more commonly in domestic cats, and 98% of cat infections are with this organism.[citation needed]It can also infect dogs and humans, however.T. mentagrophyteshas a major reservoir inrodents,but can also infect petrabbits,dogs, and horses.M. gypseumis a soil organism and is often contracted from gardens and other such places. Besides humans, it may infect rodents, dogs, cats, horses, cattle, andswine.[27]

Treatment

Pet animals

Treatment requires both systemic oral treatment with most of the same drugs used in humans—terbinafine, fluconazole, or itraconazole—as well as a topical "dip" therapy.[28]

Because of the usually longer hair shafts in pets compared to those of humans, the area of infection and possibly all of the longer hair of the pet must be clipped to decrease the load of fungal spores clinging to the pet's hair shafts. However, close shaving is usually not done because nicking the skin facilitates further skin infection.

Twice-weekly bathing of the pet with dilutedlime sulfurdip solution is effective in eradicating fungal spores. This must continue for 3 to 8 weeks.[29]

Washing of household hard surfaces with 1:10 householdsodium hypochloritebleachsolution is effective in killing spores, but it is too irritating to be used directly on hair and skin.

Pet hair must be rigorously removed from all household surfaces, and then thevacuum cleanerbag, and perhaps even the vacuum cleaner itself, discarded when this has been done repeatedly. Removal of all hair is important, since spores may survive 12 months or even as long as two years on hair clinging to surfaces.[30]

Cattle

Inbovines,an infestation is difficult to cure, assystemic treatmentis uneconomical. Local treatment withiodinecompounds is time-consuming, as it needs scraping of crusty lesions. Moreover, it must be carefully conducted usinggloves,lest the worker become infested.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, superficial fungal infections caused by dermatophytes are estimated to infect around 20-25% of the population and it is thought that dermatophytes infect 10-15% of the population during their lifetime.[31][32]The highestincidenceof superficial mycoses result from dermatophytoses which are mostprevalentin tropical regions.[31][33]Onychomycosis, a common infection caused by dermatophytes, is found with varying prevalence rates in many countries.[34]Tinea pedis+ onychomycosis,Tinea corporis,Tinea capitisare the most common dermatophytosis found in humans across the world.[34]Tinea capitishas a greater prevalence in children.[31]The increasing prevalence of dermatophytes resulting inTinea capitishas been causingepidemicsthroughout Europe and America.[34]In pets, cats are the most affected by dermatophytosis.[35]Pets are susceptible to dermatophytoses caused byMicrosporum canis,Microsporum gypseum,andTrichophyton.[35]For dermatophytosis in animals, risk factors depend on age, species, breed, underlying conditions, stress, grooming, and injuries.[35]

Numerous studies have foundTinea capitisto be the most prevalent dermatophyte to infect children across the continent of Africa.[32]Dermatophytosis has been found to be most prevalent in children ages 4 to 11, infecting more males than females.[32]Lowsocioeconomic statuswas found to be a risk factor forTinea capitis.[32]Throughout Africa, dermatophytoses are common in hot- humid climates and with areas of overpopulation.[32]

Chronicityis a common outcome for dermatophytosis in India.[33]The prevalence of dermatophytosis in India is between 36.6 and 78.4% depending on the area, clinical subtype, and dermatophyte isolate.[33]Individuals ages 21–40 years are most commonly affected.[33]

A 2002 study looking at 445 samples of dermatophytes in patients in Goiânia, Brazil found the most prevalent type to beTrichophyton rubrum(49.4%), followed byTrichophyton mentagrophytes(30.8%), andMicrosporum canis(12.6%).[36]

A 2013 study looking at 5,175 samples ofTineain patients in Tehran, Iran found the most prevalent type to beTinea pedis(43.4%), followed byTinea unguium.(21.3%), andTinea cruris(20.7%).[37]

See also

- Lichen planus—An autoimmune disease that produces similar skin blotching to ringworm.

- Mycobiota—A group of all thefungipresent in a particular niche like the human body.

References

- ^abcde"Symptoms of Ringworm Infections".CDC.December 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2016.Retrieved5 September2016.

- ^abcde"Definition of Ringworm".CDC.December 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2016.Retrieved5 September2016.

- ^abcde"Ringworm Risk & Prevention".CDC.December 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 7 September 2016.Retrieved5 September2016.

- ^abcdeDomino FJ, Baldor RA, Golding J (2013).The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2014.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1226.ISBN9781451188509.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-09-15.

- ^abc"Diagnosis of Ringworm".CDC.December 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 8 August 2016.Retrieved5 September2016.

- ^Teitelbaum JE (2007).In a Page: Pediatrics.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 274.ISBN9780781770453.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-04-26.

- ^abc"Treatment for Ringworm".CDC.December 6, 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2016.Retrieved5 September2016.

- ^abMahmoud A. Ghannoum, John R. Perfect (24 November 2009).Antifungal Therapy.CRC Press. p. 258.ISBN978-0-8493-8786-9.Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV (2012).Dermatology(3 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1255.ISBN978-0702051821.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-09-15.

- ^Hainer BL (2003)."Dermatophyte Infections".Am Fam Physician.67(1): 101–109.PMID12537173.

- ^Klemm L (2 April 2008)."Keeping footloose on trips".The Herald News.Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2009.

- ^Fort Dodge Animal Health:Milestones from Wyeth. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^"Ringworm In Your Dog, Cat And Other Pets".Vetspace.Retrieved14 November2020.

- ^"Insol Dermatophyton 5x2 ml".GROVET - The veterinary warehouse.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-08-17.Retrieved2016-02-01.

- ^F. Rochette, M. Engelen, H. Vanden Bossche (2003), "Antifungal agents of use in animal health - practical applications",Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics,26(1): 31–53,doi:10.1046/j.1365-2885.2003.00457.x,PMID12603775

- ^abKyle AA, Dahl MV (2004). "Topical therapy for fungal infections".Am J Clin Dermatol.5(6): 443–51.doi:10.2165/00128071-200405060-00009.PMID15663341.S2CID37500893.

- ^McClellan KJ, Wiseman LR, Markham A (July 1999). "Terbinafine. An update of its use in superficial mycoses".Drugs.58(1): 179–202.doi:10.2165/00003495-199958010-00018.PMID10439936.S2CID195691703.

- ^Tinea~treatmentateMedicine

- ^Tinea Corporis~treatmentateMedicine

- ^"Antifungal agents for common paediatric infections".Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol.19(1): 15–8. January 2008.doi:10.1155/2008/186345.PMC2610275.PMID19145261.

- ^Gupta AK, Cooper EA (2008). "Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis".Mycopathologia.166(5–6): 353–67.doi:10.1007/s11046-008-9109-0.PMID18478357.S2CID24116721.

- ^"Ringworm on Body Treatment"ateMedicineHealth

- ^Sequeira, J.H. (1906)."The Varieties of Ringworm and Their Treatment"(PDF).British Medical Journal.2(2378): 193–196.doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2378.193.PMC2381801.PMID20762800.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2009-11-22.

- ^Mrs. M. Grieve.A Modern Herbal.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-03-25.

- ^Scott DW (2007).Colour Atlas of Animal Dermatology.Blackwell.ISBN978-0-8138-0516-0.

- ^abDavid W. Scott, Colour Atlas of Animal Dermatology, Blackwell Publishing Professional 2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014, USA; ISBN 978-0-8138-0516-0/2007.

- ^"General ringworm information".Ringworm.au.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-12-21.Retrieved2011-01-10.

- ^"Facts About Ringworm".Archivedfrom the original on 2011-10-06.Retrieved2011-10-03.Detailed veterinary discussion of animal treatment

- ^"Veterinary treatment site page".Marvistavet. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-01-04.Retrieved2011-01-10.

- ^"Persistence of spores".Ringworm.au.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-12-21.Retrieved2011-01-10.

- ^abcPires, C. A. A., Cruz, N. F. S. da, Lobato, A. M., Sousa, P. O. de, Carneiro, F. R. O., & Mendes, A. M. D. (2014). Clinical, epidemiological, and therapeutic profile of dermatophytosis.Anais Brasileiros de Dermatología,89(2), 259–264.[1]

- ^abcdeOumar Coulibaly, Coralie L'Ollivier, Renaud Piarroux, Stéphane Ranque, Epidemiology of human dermatophytoses in Africa,Medical Mycology,Volume 56, Issue 2, February 2018, Pages 145–161.

- ^abcdRajagopalan, M., Inamadar, A., Mittal, A., Miskeen, A. K., Srinivas, C. R., Sardana, K., Godse, K., Patel, K., Rengasamy, M., Rudramurthy, S., & Dogra, S. (2018). Expert Consensus on The Management of Dermatophytosis in India (ECTODERM India).BMC dermatology,18(1), 6.[2]

- ^abcHayette, M.-P., & Sacheli, R. (2015). Dermatophytosis, Trends in Epidemiology and Diagnostic Approach.Current Fungal Infection Reports,9(3), 164–179.[3]

- ^abcGordon, E., Idle, A., & DeTar, L. (2020). Descriptive epidemiology of companion animal dermatophytosis in a Canadian Pacific Northwest animal shelter system.The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne,61(7), 763–770.

- ^Costa, M., Passos, X. S., Hasimoto e Souza, L. K., Miranda, A. T. B., Lemos, J. de A., Oliveira, J., & Silva, M. do R. R. (2002). Epidemiology and etiology of dermatophytosis in Goiânia, GO, Brazil.Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical,35(1), 19–.

- ^Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A., Makimura, K., de Hoog, S., Shidfar, M. R., Zaini, F., Eshraghian, M., Naghan, P. A., & Mirhendi, H. (2013). Molecular epidemiology of dermatophytosis in Tehran, Iran, a clinical and microbial survey.Medical Mycology (Oxford),51(2), 203–207.[4]

Further reading

- Pietro Nenoff, Constanze Krüger, Gabriele Ginter-Hanselmayer, Hans-Jürgen Tietz (2014).Mycology– an update.Part 1: Dermatomycoses: Causative agents, epidemiology and pathogenesis

- Weitzman I, Summerbell RC (1995)."The dermatophytes".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.8(2): 240–259.doi:10.1128/cmr.8.2.240.PMC172857.PMID7621400.

External links

- Tinea photo library at DermnetArchived2008-10-15 at theWayback Machine