Trade route

| Business logistics |

|---|

| Distribution methods |

| Management systems |

| Industry classification |

Atrade routeis alogistical networkidentified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowinggoodsto reach distantmarkets,a single trade route contains long-distancearteries,which may further be connected to smaller networks of commercial and noncommercial transportation routes. Among notable trade routes was theAmber Road,which served as a dependable network for long-distance trade.[1]Maritime tradealong theSpice Routebecame prominent during theMiddle Ages,when nations resorted to military means for control of this influential route.[2]During the Middle Ages, organizations such as theHanseatic League,aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade became increasingly prominent.[3]

Inmodern times,commercial activity shifted from the major trade routes of theOld Worldto newer routes between modernnation-states.This activity was sometimes carried out without traditional protection of trade and under internationalfree-tradeagreements, which allowed commercial goods to cross borders with relaxed restrictions.[4]Innovative transportation of modern times includespipeline transportand the relatively well-known trade involvingrail routes,automobiles,andcargo airlines.

History

[edit]Development of early routes

[edit]Early development

[edit]Long-distance trade routes were developed in theChalcolithicperiod. The period from the middle of the 2nd millenniumBCEto the beginning of theCommon Erasaw societies in Southeast Asia, Western Asia, the Mediterranean, China, and the Indian subcontinent develop major transportation networks for trade.[5]

One of the vital instruments which facilitated long-distance trade wasportageand the domestication ofbeasts of burden.[6]Organized caravans, visible by the 2nd millennium BCE,[7]could carry goods across a large distance as fodder was mostly available along the way.[6]The domestication ofcamelsallowedArabiannomadsto control the long-distance trade inspicesandsilkfrom theFar Eastto theArabian Peninsula.[8]Caravans were useful in long-distance trade largely for carrying luxury goods, the transportation of cheaper goods across large distances was not profitable for caravan operators.[9]With productive developments in iron and bronze technologies, newer trade routes – dispensing innovations of civilizations – began to rise.[10]

Maritime trade

[edit]

Navigation was known inSumerbetween the 4th and the 3rd millennium BCE.[7]TheEgyptianshad trade routes through theRed Sea,importing spices from the "Land of Punt"(East Africa) and from Arabia.[11]

In Asia, the earliest evidence of maritime trade was theNeolithictrade networks of theAustronesian peoplesamong which is thelingling-ojadeindustry of thePhilippines,Taiwan,southernVietnamand peninsularThailand.It also included the long-distance routes of Austronesian traders fromIndonesiaandMalaysiaconnectingChinawithSouth Asiaand theMiddle Eastsince approximately 500 BCE. It facilitated the spread of Southeast Asian spices and Chinese goods to the west, as well as the spread ofHinduismandBuddhismto the east. This route would later become known as theMaritime Silk Road,although that is a misnomer, since spices, rather than silk, were traded along this route. Many Austronesian technologies like theoutriggerandcatamaran,as well as Austronesian ship terminologies, still persist in many of the coastal cultures in theIndian Ocean.[12][13][14]

Maritime trade began with safer coastal trade and evolved with the manipulation of the monsoon winds, soon resulting in trade crossing boundaries such as theArabian Seaand theBay of Bengal.[15]South Asiahad multiple maritime trade routes which connected it toSoutheast Asia,thereby making the control of one route resulting in maritime monopoly difficult.[15]Indian connections to various Southeast Asian states buffered it from blockages on other routes.[15]By making use of the maritime trade routes,bulk commodity tradebecame possible for theRomansin the 2nd century BCE.[16]A Roman trading vessel could span the Mediterranean in a month atone-sixtieth the costofover-land routes.[17]

Visible trade routes

[edit]

The peninsula ofAnatolialay on the commercial land routes to Europe from Asia as well as the sea route from the Mediterranean to theBlack Sea.[18]Records from the 19th century BCE attest to the existence of anAssyrianmerchant colony atKaneshinCappadocia(now in modernTurkey).[18]Trading networks of the Old World included theGrand Trunk Roadof India and theIncense RoadofArabia.[5]A transportation network consisting of hard-surfaced highways, using concrete made from volcanic ash and lime, was built by the Romans as early as 312 BCE, during the times of theCensorAppius Claudius Caecus.[19]Parts of the Mediterranean world,Roman Britain,Tigris-Euphratesriver system and North Africa fell under the reach of this network at some point of their history.[19]

According to Robert Allen Denemark (2000):[20]

"The spread of urban trading networks, and their extension along thePersian Gulfand eastern Mediterranean, created a complex molecular structure of regional foci so that as well as the zonation of core and periphery (originally created aroundMesopotamia) there was a series of interacting civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, theIndus Valley;then alsoSyria,central Anatolia (Hittites) and theAegean(MinoansandMycenaeans). Beyond this was a margin which included not onlytemperateareas such as Europe, but the drysteppecorridor ofcentral Asia.This was truly a world system, even though it occupied only a restricted portion of the western Old World. Whilst each civilization emphasized its ideological autonomy, all were identifiably part of a common world of interacting components. "

These routes – spreadingreligion,trade and technology – have historically been vital to the growth of urban civilization.[21]The extent of development of cities, and the level of their integration into a larger world system, has often been attributed to their position in various active transport networks.[22]

Historic trade routes

[edit]Combined land and waterway routes

[edit]Incense Route

[edit]The Incense Route served as a channel for trading of Indian, Arabian and East Asian goods.[23]The incense trade flourished from South Arabia to the Mediterranean between roughly the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[24]This trade was crucial to the economy ofYemenand thefrankincenseandmyrrhtrees were seen as a source of wealth by its rulers.[25]

Ptolemy II Philadelphus,emperor ofPtolemaic Egypt,may have forged an alliance with theLihyanitesin order to secure the incense route atDedan,thereby rerouting the incense trade from Dedan to the coast along the Red Sea to Egypt.[26]I. E. S. Edwardsconnects theSyro-Ephraimite Warto the desire of theIsraelitesand theAramaeansto control the northern end of the Incense route, which ran up from Southern Arabia and could be tapped by commandingTransjordan.[27]

Gerrha– inhabited byChaldeanexiles fromBabylon– controlled the Incense trade routes across Arabia to the Mediterranean and exercised control over the trading ofaromaticsto Babylon in the 1st century BCE.[28]TheNabateansexercised control over the routes along the Incense Route, and their hold was challenged – without success – byAntigonus Cyclops,emperor of Syria.[29]The Nabatean control over trade further increased and spread in many directions.[29]

The replacement of Greece by theRoman empireas the administrator of the Mediterranean basin led to the resumption of direct trade with the East and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of the south.[30]According to Milo Kearney (2003) "The South Arabs in protest took to pirate attacks over the Roman ships in theGulf of Aden.In response, the Romans destroyed Aden and favored the Western Abyssinian coast of the Red Sea. "[31]Indian ships sailed to Egypt as the maritime routes of Southern Asia were not under the control of a single power.[30]

Pre-Columbian trade

[edit]Some similarities between theMesoamericanand theAndeancultures suggest that the two regions became a part of a wider world system, as a result of trade, by the 1st millennium BCE.[32]The current academic view is that the flow of goods across the Andean slopes was controlled by institutions distributing locations to local groups, who were then free to access them for trading.[33]This trade across the Andean slopes – described sometimes as "vertical trade" – may have overshadowed the long-distance trade between the people of the Andes and the neighboring forests.[33]TheCallawayaherbalists traded in tropical plants between 6th and the 10th centuries, while copper was dealt by specialized merchants in thePeruvianvalley ofChincha.[33]Long-distance trade may have seen local elites resorting to struggle in order for manipulation and control.[33]

Prior to theIncadominance, specialized long-distance merchants provided the highlanders with goods such as gold nuggets, copper hatchets, cocoa, salt etc. for redistribution among the locals, and were key players in the politics of the region.[34]Hatchet shaped copper currency was produced by thePeruvian people,in order to obtain valuables frompre ColumbianEcuador.[34]A maritime exchange system stretched from the west coast of Mexico to southernmost Peru, trading mostly inSpondylus,which represented rain and fertility and was considered the principal food of the gods by the people of theInca empire.[34]Spondylus was used in elite rituals, and the effective redistribution of it had political effect in the Andes during the pre-Hispanic times.[34]

Predominantly overland routes

[edit]Silk Road

[edit]

The Silk Road was one of the first trade routes to join theEasternand theWestern worlds.[35]According to Vadime Elisseeff (2000):[35]

"Along the Silk Roads, technology traveled, ideas were exchanged, and friendship and understanding between East and West were experienced for the first time on a large scale. Easterners were exposed to Western ideas and life-styles, and Westerners, too, learned about Eastern culture and its spirituality-oriented cosmology.Buddhismas an Eastern religion received international attention through the Silk Roads. "

Cultural interactions patronized often by powerful emperors, such asKanishka,led to development of art due to introduction of a rich variety of influences.[35]Buddhist missionsthrived along the Silk Roads, partly due to the conducive intermi xing of trade and cultural values, which created a series of safe stoppages for both thepilgrimsand thetraders.[36]The Silk Roads led to the creation of a merchant class urban centers and the growth of trade-based economies. Among the frequented routes of the Silk Route was theBurmeseroute extending fromBhamo,which served as a path forMarco Polo's visit toYunnanand Indian Buddhist missions toCantonin order to establishBuddhist monasteries.[37]This route – often under the presence of hostile tribes – also finds mention in the works ofRashid-al-Din Hamadani.[37]

Grand Trunk Road

[edit]

The Grand Trunk Road – connectingChittagongin Bangladesh toPeshawarin Pakistan – has existed for over two and a halfmillennia.[38]One of the important trade routes of the world, this road has been a strategic artery withfortresses,halting posts,wells,post offices,milestonesand other facilities.[38]Part of this road through Pakistan also coincided with the Silk Road.[38]

This highway has been associated with emperorsChandragupta MauryaandSher Shah Suri,the latter became synonymous with this route due to his role in ensuring the safety of the travelers and the upkeep of the road.[39]Emperor Sher Shah widened and realigned the road to other routes, and provided approximately 1700 roadsideinnsthrough his empire.[39]These inns provided free food and lodgings to the travelers regardless of their status.[39]

The British occupation of this road was of special significance for theBritish Rajin India.[40]Bridges, pathways and newer inns were constructed by the British for the first thirty-seven years of their reign since the occupation ofPunjabin 1849.[40]The British followed roughly the same alignment as the old routes, and at some places the newer routes ran parallel to the older routes.[40]

Vadime Elisseeff (2000) comments on the Grand Trunk Road:[41]

"Along this road marched not only the mighty armies of conquerors, but also the caravans of traders, scholars, artists, and common folk. Together with people, moved ideas, languages, customs, and cultures, not just in one, but in both directions. At different meeting places – permanent as well as temporary – people of different origins and from different cultural backgrounds, professing different faiths and creeds, eating different foods, wearing different clothes, and speaking different languages and dialects would meet one another peacefully. They would understand one another's food, dress, manner, and etiquette, and even borrow words, phrases, idioms and, at times, whole languages from others."

Amber Road

[edit]The Amber Road was a European trade route associated with the trade and transport ofamber.[1]Amber satisfied the criteria for long-distance trade as it was light in weight and was in high demand for ornamental purposes around the Mediterranean.[1]Before the establishment of Roman control over areas such asPannonia,the Amber Road was virtually the only route available for long-distance trade.[1]

Towns along the Amber Road began to rise steadily during the 1st century CE, despite the troop movements underTitus Flavius Vespasianusand his sonTitus Flavius Domitianus.[42] Under the reign ofTiberius Caesar Augustus,the Amber Road was straightened and paved according to the prevailing urban standards.[43]Roman towns began to appear along the road, initially founded near the site ofCelticoppida.[43]

The 3rd century saw theDanuberiver become the principal artery of trade, eclipsing the Amber Road and other commercial routes.[1]The redirection of investment to the Danubian forts saw the towns along the Amber Road growing slowly, though yet retaining their prosperity.[44]The prolonged struggle between the Romans and the barbarians further left its mark on the towns along the Amber Road.[45]

Via Maris

[edit]

Via Maris, literallyLatinfor "the way of the sea",[46]was an ancient highway used by the Romans and theCrusaders.[47]The states controlling the Via Maris were in a position to grant access for trade to their own citizens and collect tolls from the outsiders to maintain the trade route.[48]The nameVia Marisis a Latin translation of aHebrewphrase related toIsaiah.[47]Due to thebiblicalsignificance of this ancient route, many attempts to find its present-day location have been made byChristianpilgrims.[47]13th-century traveler and pilgrim Burchard ofMount Zionrefers to the Via Maris route as a way leading along the shore of theSea of Galilee.[47]

Trans Saharan trade

[edit]

Early Muslim writings confirm that the people ofWest Africaoperated a sophisticated network of trade, usually under the authority of a monarch who levied taxes and provided bureaucratic and military support to his kingdom.[50]Sophisticated mechanisms for the economic and political development of the involved African areas were in place beforeIslamfurther strengthened trade, towns and government in western Africa.[50]The capital, court and trade of the region find mention in the works of scholarAbū 'Ubayd 'Abd Allāh al-Bakrī;the mainstay of the transSaharantrade was gold and salt.[50]

The powerful Saharan tribes,Berberin origin and later adapting to Muslim and Arab cultures, controlled the channels to western Africa by making efficient use of horse-drawn vehicles and pack animals.[50]TheSonghaiengaged in a struggle against the Sa'di dynasty ofMoroccoover the control of the trans Saharan trade, resulting in damage on both sides and a weak Moroccan victory, further strengthening the uninvolved Saharan tribes.[50]Struggles and disturbances continued till the 14th century, by which theMandémerchants were trading with theHausa,betweenLake Chadand theNiger.[50]Newer trade routes developed following extension of trade.[50]

Predominantly maritime routes

[edit]Austronesian maritime trade network

[edit]

Long-distance maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean also had run by theAustronesian peoplesofIsland Southeast Asia.[52][51]They established trade routes withSouthern IndiaandSri Lankaas early as 1500 BCE, ushering an exchange of material culture (likecatamarans,outrigger boats,sewn-plank boats, andpaan) andcultigens(likecoconuts,sandalwood,bananas,sugarcane,cloves,andnutmeg); as well as connecting the material cultures of India and China..[53][54][55][14]They constituted the majority of the Indian Ocean component of thespice tradenetwork.Indonesians,in particular were trading in spices (mainlycinnamonandcassia) withEast Africausingcatamaranand outrigger boats and sailing with the help of theWesterliesin the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far asAfricaand theArabian Peninsula,resulting in the Austronesian colonization ofMadagascarby the first half of the first millennium AD. It continued up to historic times, later becoming theMaritime Silk Road.[51][13][14][56][57]This trade network also included smaller trade routes withinIsland Southeast Asia,including thelingling-ojade network, and thetrepangingnetwork.

In easternAustronesia,various traditional maritime trade networks also existed. Among them was the ancientLapita trade networkofIsland Melanesia;[58]theHiri trade cycle,Sepik Coast exchange,and theKula ringofPapua New Guinea;[58]the ancient trading voyages inMicronesiabetween theMariana Islandsand theCaroline Islands(and possibly alsoNew Guineaand thePhilippines);[59]and the vast inter-island trade networks ofPolynesia.[60]

Roman-India routes

[edit]

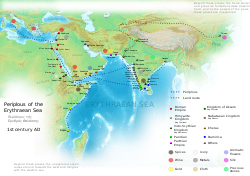

ThePtolemaic dynasty(305 to 30 BC) had initiatedGreco-Romanmaritime trade contact with India using the Red Sea ports.[61]The Roman historianStrabomentions a vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt, indicating that monsoon was known and manipulated for trade in his time.[62]By the time ofAugustusup to 120 ships were setting sail every year fromMyos Hormosto India,[63]trading in a diverse variety of goods.[64]Arsinoe,[65]Berenice Troglodyticaand Myos Hormos were the principal Roman ports involved in this maritime trading network,[66]while the Indian ports includedBarbaricum,Barygaza,MuzirisandArikamedu.[64]

The Indians were present inAlexandria[67]and the Christian andJewishsettlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the fall of the Roman empire,[68]which resulted in Rome's loss of theRed Seaports,[69]previously used to secure trade with India by the Greco-Roman world since the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[65]

Hanseatic trade

[edit]

Shortly before the 12th century theGermansplayed a relatively modest role in the north European trade.[70]However, this was to change with the development of Hanseatic trade, as a result of which German traders became prominent in theBalticand theNorth Searegions.[71]Following the death ofEric VI of Denmark,German forces attacked and sacked Denmark, bringing with them artisans and merchants under the new administration which controlled the Hansa regions.[72]During the third quarter of the 14th century the Hanseatic trade faced two major difficulties: economic conflict with theFlandersand hostilities with Denmark.[3]These events led to the formation of an organized association of Hanseatic towns, which replaced the earlier union of German merchants.[3]This new Hansa of the towns, aimed at protecting interests of the merchants and trade, was prominent for the next hundred and fifty years.[3]

Philippe Dollinger associates the downfall of the Hansa to a new alliance betweenLübeck,HamburgandBremen,which outshadowed the older institution.[73]He further sets the date of dissolution of the Hansa at 1630[73]and concludes that the Hansa was almost entirely forgotten by the end of the 18th century.[74]ScholarGeorg Friedrich Sartoriuspublished the firstmonographregarding the community in the early years of the 19th century.[74]

From the Varangians to the Greek

[edit]The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks (Russian:Путь "из варяг в греки",Put' iz varyag v greki,Swedish:Vägen från varjagerna till grekerna,Greek:Εμπορική Οδός Βαράγγων – Ελλήνων,Emporikḗ Odós Varángōn-Ellḗnōn) was a trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Byzantine Empire. The route allowed traders along the route to establish a direct prosperous trade with Byzantium, and prompted some of them to settle in the territories of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

The route began in Scandinavian trading centres such as Birka, Hedeby, and Gotland, crossed the Baltic Sea entered the Gulf of Finland, followed the Neva River into the Lake Ladoga. Then it followed the Volkhov River, upstream past the towns of Staraya Ladoga and Velikiy Novgorod, crossed Lake Ilmen, and up the Lovat River. From there, ships had to be portaged to the Dnieper River near Gnezdovo. A second route from the Baltic to the Dnieper was along the Western Dvina (Daugava) between the Lovat and the Dnieper in the Smolensk region, and along the Kasplya River to Gnezdovo. Along the Dnieper, the route crossed several majorrapidsand passed through Kiev, and after entering the Black Sea followed its west coast to Constantinople.

Maritime republics' Mediterranean trade

[edit]

The economic growth ofEuropearound the year 1000, together with the lack of safety on the mainland trading routes, eased the development of major commercial routes along the coast of theMediterranean.The growing independence of some coastal cities gave them a leading role in this commerce:Maritime Republics,Italian "Repubbliche Marinare"(Venice,Genoa,Amalfi,Pisa,Gaeta,AnconaandRagusa[75]), developed their own "empires" in theMediterraneanshores.

From the 8th until the 15th century, Venetian and genoese merchants held the monopoly of European trade with the Middle East. Thesilkandspice trade,involvingspices,incense,herbs,drugsandopium,made these Mediterranean city-states phenomenally rich. Spices were among the most expensive and demanded products of the Middle Ages. They were all imported from Asia and Africa. Muslim traders – mainly descendants of Arab sailors fromYemenandOman– controlled maritime routes throughout the Indian Ocean, tapping source regions in theFar Eastand shipping for trading emporiums in India, westward toOrmusinPersian GulfandJeddahin theRed Sea.From there, overland routes led to the Mediterranean coasts. Venetian merchants distributed then the goods through Europe until the rise of theOttoman Empire,that eventually led to thefall of Constantinoplein 1453, barring Europeans from important combined-land-sea routes.

Spice Route

[edit]

As trade between India and theGreco-Roman worldincreased[76]spices became the main import from India to the Western world,[77]bypassing silk and other commodities.[78]The Indian commercial connection with South East Asia proved vital to the merchants of Arabia and Persia during the 7th and 8th centuries.[79]

TheAbbasidsused Alexandria,Damietta,AdenandSirafas entry ports to India and China.[80]Merchants arriving from India in the port city of Aden paid tribute in form ofmusk,camphor,ambergrisand sandalwood toIbn Ziyad,thesultanof Yemen.[80]Moluccanproducts shipped across the ports of Arabia to the Near East passed through the ports of India andSri Lanka.[81]Indian exports of spices find mention in the works of Ibn Khurdadhbeh (850 CE), al-Ghafiqi (1150), Ishak bin Imaran (907) and Al Kalkashandi (14th century).[81]After reaching either the Indian or the Sri Lankan ports, spices were sometimes shipped to East Africa, where they were used for many purposes, including burial rites.[81]

On the orders ofManuel I of Portugal,four vessels under the command of navigator Vasco da Gama rounded theCape of Good Hope,continuing to the eastern coast of Africa toMalindito sail across the Indian Ocean toCalicut.[82]The wealth of theIndieswas now open for the Europeans to explore; thePortuguese Empirewas one of the early European empires to grow from spice trade.[82]

Maritime Jade Road

[edit]

TheMaritime Jade Roadwas an extensive trading network connecting multiple areas in Southeast and East Asia. Its primary products were made of jade mined fromTaiwanby animistTaiwanese indigenous peoplesand processed mostly in thePhilippinesby animist indigenous Filipinos, especially inBatanes,Luzon,andPalawan.Some were also processed inVietnam,while the peoples ofMalaysia,Brunei,Singapore,Thailand,Indonesia,andCambodiaalso participated in the massive animist-led trading network. Participants in the network at the time had a majority animist population. The maritime road is one of the most extensive sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the prehistoric world. It was in existence for at least 3,000 years, where its peak production was from 2000 BCE to 500 CE, older than theSilk Roadin mainland Eurasia or the laterMaritime Silk Road.A notable artifact that the trading network made, theLingling-oartifacts, were made by artisans around 500 BCE. The network began to wane during its final centuries from 500 CE until 1000 CE. The entire period of the network was a golden age for the diverse animist societies of the region.[83][84][85][86]

Maritime Silk Road

[edit]

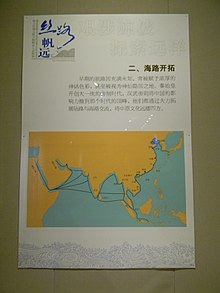

The Maritime Silk Road refers to themaritimesection of historicSilk Roadthat connectsChina,Southeast Asia,theIndian subcontinent,Arabian Peninsula,Somaliaand all the way toEgyptand finallyEurope.It flourished between 2nd-century BCE and 15th-century CE.[87]Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated byAustronesiansailors in Southeast Asia, and byPersianandArabtraders in theArabian Sea.[88]

The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlierAustronesianspice tradenetworks ofIslander Southeast AsianswithSri LankaandSouthern India(established 1000 to 600 BCE), as well as the earlierMaritime Jade Road,known forlingling-oartifacts, in Southeast Asia, based inTaiwanand thePhilippines.[12][14]For most of its history, Austronesianthalassocraciescontrolled the flow of the Maritime Silk Road, especially thepolitiesaround thestraitsofMalaccaandBangka,theMalay Peninsula,and theMekong Delta;although Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to theIndianizationof these regions. Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, althoughTamilandPersiantraders also sailed them.[88]The route was influential in the early spread ofHinduismandBuddhismto the east.[89]

China later built its own fleets starting from theSong dynastyin the 10th century, participating directly in the trade route up until the end of theColonial Eraand the collapse of theQing dynasty.[88]

Modern routes

[edit]

The modern times saw development of newer means of transport and often controversial free trade agreements, which altered the political and logistical approach prevalent during the Middle Ages. Newer means of transport led to the establishment of new routes, and countries opened up borders to allow trade in mutually agreed goods as per the prevailing free trade agreement. Some old trading route were reopened during the modern times, although in different political and logistical scenarios.[90]The entry of harmful foreign pollutants by the way of trade routes has been a cause of alarm during the modern times.[91]A conservative estimate stresses that future damages from harmful animal and plant diseases may be as high as 134 billion US dollars in the absence of effective measures to prevent the introduction of unwanted pests through various trade routes.[91]

Wagonway routes

[edit]Networks, like theSanta Fe Trailand theOregon Trail,became prominent in the United States withwagon trainsgaining popularity as a mode of long-distance overland transportation for both people and goods.[92]TheOregon–Californiaroutes were highly organized with planned rendezvous locations and essential supplies.[92]The settlers in the United States used these wagon trains – sometimes made up of 100 of moreConestoga wagons– for westward emigration during the 18th and the 19th centuries.[92]Among the challenges faced by the wagon route operators were crossing rivers, mountains and hostileNative Americans.[92]Preparations were also made according to the weather and protection of trade and travelers was ensured by a few guards on horseback.[92] Wagon freighting was also essential to American growth until it was replaced by therailroadand thetruck.[92]

Railway routes

[edit]

The 1844 Railway act of England compelled at least onetrainto a station every day with the third class fares priced at apennya mile.[93]Trade benefited as the workers and the lower classes had the ability to travel to other towns frequently.[94]Suburban communities began to develop and towns began to spread outwards.[94]The British constructed a vast railway network in India, but it was considered to serve a strategic purpose in addition to the commercial purpose.[95]The efficient use of rail routes helped in the unification of theUnited States of America,[96]and thefirst transcontinental railroadwas completed in 1869.

The modern times saw nations struggle for the control of rail routes: TheTrans-Siberian Railwaywas intended to be used by the Russian government for control ofManchuriaand later China; the German forces wanted to establishBerlin-Baghdad Railwayin order to influence the Near East; and the Austrian government planned a route fromViennatoSalonikafor control of theBalkans.[96] According to theEncyclopædia Britannica(2002):

Railroads reached their maturity in the early 20th century, as trains carried the bulk of land freight and passenger traffic in theindustrialized countriesof the world. By the mid-20th century, however, they had lost their preeminent position. The private automobile had replaced the railroad for short passenger trips, while the airplane had usurped it for long-distance travel, especially in the United States. Railroads remained effective, however, for transporting people in high-volume situations, such as commuting between the centres of large cities and their suburbs, and medium-distance travel of less than about 300 miles between urban centres.

Although railroads have lost much of the general-freight-carrying business to semi-trailer trucks, they remain the best means of transporting large volumes of such bulk commodities as coal, grain, chemicals, and ore over long distances. The development ofcontainerizationhas made the railroads more effective in handling finished merchandise at relatively high speeds. In addition, the introduction of piggyback flatcars, in which truck trailers are transported long distances on specially-designed cars, has allowed railroads to regain some of the business lost to trucking.

Modern road networks

[edit]

The advent ofmotor vehiclescreated a demand for better use of highways.[97]Roads evolved into two way roads,expressways,freewaysandtollwaysduring the modern times.[98]Existing roads were developed and highways were designed according to intended use.[97]

Truckscame into widespread use in the Western World during World War I, and quickly gained reputation as a means of long-distance transportation of goods.[99]Modern highways, such as theTrans-Canada Highway,Highway 1 (Australia)andPan-American Highwayallowed transport of goods and services across great distances. Automobiles continue to play a crucial role in the economies of the Industrialized countries, resulting in rise of businesses such as motor freight operation and truck transportation.[97]

The emission rate for cars using highways has been on a decline between 1975 and 1995 due to regulations and the introduction ofunleaded petrol.[100]This trend is especially notable since there has been a growth in vehicles and vehicle miles traveled by automobiles using these highways.[100]

Modern maritime routes

[edit]

A consistent shift from land based trade to sea-based trade has been recorded since the last three millennia.[101]The strategic advantages of port cities as trading centers are many: they are both less dependent on vital connections and less vulnerable to blockages.[102]Oceanic ports can help forge trading relationships with other parts of the world easily.[102]

Modern maritime trade routes – sometimes in the form of artificialcanalslike theSuez Canal– had visible impact on the economic and political standing of nations.[103]The opening of the Suez Canal altered British interactions with the colonies of theBritish Empireas the dynamics of transportation, trade and communication had now changed drastically.[103]Otherwaterways,like thePanama Canalplayed an important role in the histories of many nations.[104]Inland water transportation remained significantly important even as the advent of railroads and automobiles resulted in a steady decline of canals.[105]Inland water transport is still used for the transportation of bulk commodities e.g. grains, coal, and ore.[106]

Waterway commerce was historically important to Europe, particularly to Russia.[105]According to theEncyclopædia Britannica(2002): "Russia has been a significant beneficiary. Not only have inland waterways opened vast areas of its interior to development, but Moscow – linked to theWhite,Baltic,Black,Caspian,andAzovseas by canals and rivers – has become a major inland port. "[105]

Oil spillsare recorded both in case of maritime routes and pipeline routes to the main refineries.[107]Oil spills, amounting to as much as 7.56 billion liters of oil entering the oceans every year, occur due to damaged equipment or human error.[107]

The21st Century Maritime Silk Roadis a current project of the Chinese government to expand and intensify trade on the maritimeSilk Road.This is leading to major investments in ports, traffic routes and other infrastructure in Europe and Africa as well. The maritime silk road essentially runs from the Chinese coast toSingaporeandKuala Lumpur,via the Sri Lankan Colombo towards the southern tip of India, to the East AfricanMombasa,from there toDjibouti,then via theSuez Canalto the Mediterranean, there viaHaifa,IstanbulandAthensto the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub ofTriestewith its international free port and its rail connections toCentralandEastern Europeand the North Sea.[108][109][110][111][112][113]

Free trade areas

[edit]

Historically, many governments followed a policy of protection of trade.[4]Internationalfree tradebecame visible in 1860 with the Anglo-French commercial treaty, and the trend gained further momentum[why?]during the period after World War II.[4] According toThe Columbia Encyclopedia,Sixth Edition:[4]

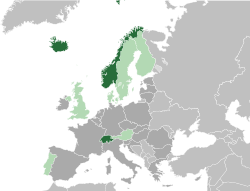

"After World War II, strong sentiment developed throughout the world against protection and high tariffs and in favor of freer trade. The results were new organizations and agreements on international trade such as theGeneral Agreement on Tariffs and Trade(1948), theBenelux Economic Union(1948), theEuropean Economic Community(Common Market, 1957), theEuropean Free Trade Association(1959),Mercosur(the Southern Cone Common Market, 1991), and theWorld Trade Organization(1995). In 1993, theNorth American Free Trade Agreement(NAFTA) was approved by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. In the early 1990s, the nations of theEuropean Union(the successor organization to theCommon Market) undertook to remove all barriers to the free movement of trade and employment across their mutual borders. "

In May 2004 the United States of America signed the American Free trade Agreement with five Central American nations.[4]

Air routes

[edit]

Air transport has become an indispensable part of modern society.[114]People have come to use air transport both for long and middle distances, with the average route length of long distances being 720 kilometers in Europe and 1220 kilometers in the US.[115]This industry annually carries 1.6 billion passengers worldwide, covers a 15 million kilometer network, and has an annual turnover of 260 billion dollars.[115]

This mode of transportation links national, international and global economies, making it vital to many other industries.[115]Newer trends ofliberalization of tradehave fostered routes among nations bound by agreements.[115]One such example, the AmericanOpen Skies policy,led to greater openness in many international markets, but some international restrictions have survived even during the present times.[115]

Express delivery through internationalcargo airlinestouched US$20 billion in 1998 and, according to the World Trade Organization, is expected to triple in 2015.[116]In 1998, 50 pure cargo-service companies operated internationally.[116]

Air transport particularly favors light, expensive and small products: electronic media rather than books, for example, and refined drugs rather than bulk food.

Pipeline networks

[edit]

The economic importance of pipeline transport – responsible for a high percentage of oil and natural gas transportation – is often unrecognized by the general public due to the lack of visibility of this mode.[117]Generally held to be safer and more economical and reliable than the other modes of transport, this mode has many advantages over rival modes, such as trucks and railways.[117]Examples of modern pipeline transport includeAlashankou-Dushanzi Crude Oil PipelineandIran-Armenia Natural Gas Pipeline.International pipeline transport projects, like theBaku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline,presently connect modern nation states – in this case,Azerbaijan,Georgiaand Turkey – through pipeline networks.[118]

In some select cases, pipelines can even transport solids, such as coal and other minerals, over long distances; short-distance transportation of goods such as grain, cement, concrete, solid wastes, pulp etc. is also feasible.[117]

Notes

[edit]- ^abcdeBurns 2003: 213.

- ^Donkin 2003: 169.

- ^abcdDollinger 1999: 62.

- ^abcde"free trade; The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05".Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2007.Retrieved22 October2013.

- ^abDenemark 2000: 274

- ^abDenemark 2000: 207

- ^abDenemark 2000: 208

- ^Stearns 2001: 41.

- ^Denemark 2000: 213.

- ^Denemark1 2000: 39.

- ^Rawlinson 2001: 11–12.

- ^abBellina, Bérénice (2014)."Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road".In Guy, John (ed.).Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century.Yale University Press. pp. 22–25.ISBN9781588395245.

- ^abDoran, Edwin Jr. (1974)."Outrigger Ages".The Journal of the Polynesian Society.83(2): 130–140. Archived fromthe originalon 18 January 2020.Retrieved20 June2019.

- ^abcdMahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.).Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts.One World Archaeology. Vol. 34.Routledge.pp. 144–179.ISBN978-0415100540.

- ^abc"Ancient Trade and Civilization | World | Aurlaea".

- ^Toutain 1979: 243.

- ^Scarre 1995.

- ^abStearns 2001: 37.

- ^abRoman road system (Encyclopædia Britannica2002).

- ^Denemark 2000: 124.

- ^Denemark 2000: 126

- ^Denemark 2000: 273.

- ^"Traders of the Gold and Incense Road".Message of the Republic of Yemen, Berlin. Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2007.

- ^"Incense Route – Desert Cities in the Negev".UNESCO.

- ^Glasse 2001: 59.

- ^Kitchen 1994: 46.

- ^Edwards 1969: 329.

- ^Larsen 1983: 56.

- ^abEckenstein 2005: 49.

- ^abLach 1994: 13.

- ^Kearney 2003: 42.

- ^Denemark 2000: 252.

- ^abcdDenemark 2000: 239.

- ^abcdDenemark 2000: 241

- ^abcElisseeff 2000: 326.

- ^Elisseeff 2000: 5.

- ^abElisseeff 2000: 14

- ^abcElisseeff 2000: 158.

- ^abcElisseeff 2000: 161.

- ^abcElisseeff 2000: 163

- ^Elisseeff 2000: 178.

- ^Burns 2003: 216.

- ^abBurns 2003: 211.

- ^Burns 2003: 229.

- ^Burns 2003: 231.

- ^Orlinsky 1981: 1064.

- ^abcdOrlinsky 1981: 1065

- ^Silver 1983: 49.

- ^"Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a modern world".Smithsonian National Museum of African art.

- ^abcdefgwestern Africa, history of (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^abcManguin, Pierre-Yves (2016)."Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships".In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.).Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World.Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76.ISBN9783319338224.

- ^Sen, Tansen (January 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century".TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia.2(1): 31–59.doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15.

- ^Olivera, Baldomero; Hall, Zach; Granberg, Bertrand (31 March 2024). "Reconstructing Philippine history before 1521: the Kalaga Putuan Crescent and the Austronesian maritime trade network".SciEnggJ.17(1): 71–85.doi:10.54645/2024171ZAK-61.

- ^Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008)."The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond".eJournal of Indian Medicine.1:87–140.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2019.

- ^Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.).Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry.Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185.ISBN9780521419994.

- ^Doran, Edwin B. (1981).Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins.Texas A&M University Press.ISBN9780890961070.

- ^Blench, Roger (2004)."Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region".Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association.24(The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- ^abFriedlaender, Jonathan S. (2007).Genes, Language, & Culture History in the Southwest Pacific.Oxford University Press. p. 28.ISBN9780195300307.

- ^Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992).Ancient Chamorro Society.Bess Press. p. 195.ISBN9781880188057.

- ^Borrell, Brendan (27 September 2007)."Stone tool reveals lengthy Polynesian voyage".Nature:news070924–9.doi:10.1038/news070924-9.S2CID161331467.

- ^Shaw 2003: 426.

- ^Young 2001: 20.

- ^"The Geography of Strabo".Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917.

- ^abHalsall, Paul."Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century".Fordham University.

- ^abLindsay 2006: 101

- ^Freeman 2003: 72

- ^Lach 1994: 18.

- ^Curtin 1984: 100.

- ^Holl 2003: 9.

- ^Dollinger 1999: 9.

- ^Dollinger 1999: 42.

- ^Dollinger 1999: page 54

- ^abDollinger 1999: page xix

- ^abDollinger 1999: xx.

- ^G. Benvenuti - Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia - Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini,Le repubbliche del mare,Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma.

- ^At any rate, whenGalluswas prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended theNileas far asSyeneand the frontiers ofEthiopia,and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise. – Strabo (II.5.12.);Source.

- ^Ball 2000: 131

- ^Ball 2000: 137.

- ^Donkin 2003: 59.

- ^abDonkin 2003: 91–92.

- ^abcDonkin 2003: 92

- ^abGama, Vasco daArchived14 February 2009 at theWayback Machine.The Columbia Encyclopedia,Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press.

- ^Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- ^Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan’s relations with the Philippines date back millenia, so it’s a mystery that it’s not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- ^Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- ^Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- ^"Maritime Silk Road".SEAArch.Archived fromthe originalon 5 January 2014.Retrieved20 June2019.

- ^abcGuan, Kwa Chong (2016)."The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea"(PDF).NSC Working Paper(23): 1–30. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 March 2021.Retrieved20 June2019.

- ^Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century".TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia.2(1): 31–59.doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15.S2CID140665305.

- ^Historic India–China link opens (BBC)

- ^abSchulze & Ursprung 2003: 104

- ^abcdefwagon train (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^Seaman 1973: 29–30.

- ^abSeaman 1973: 30.

- ^Seaman 1973: 348

- ^abSeaman 1973: 379.

- ^abcautomotive industry (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^roads and highways (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^truck (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^abSchwela & Zali 2003: 156

- ^Denemark 2000: 282

- ^abDenemark 2000: 283.

- ^abCarter 2004.

- ^Major 1993.

- ^abccanal (Encyclopædia Britannica2002).

- ^canals and inland waterways (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002).

- ^abKrech et al. 2003: 966

- ^Guido Santevecchi: Di Maio e la Via della Seta: «Faremo i conti nel 2020», siglato accordo su Trieste in Corriere della Sera: 5. November 2019.

- ^Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstraße. Frankfurt am Main 2017, pp 59.

- ^"Global shipping and logistic chain reshaped as China’s Belt and Road dreams take off" in Hellenic Shipping News, 4 December 2018.

- ^Bernhard Simon: Can The New Silk Road Compete with the Maritime Silk Road? in The Maritime Executive, 1 January 2020.

- ^Harry de Wilt: Is One Belt, One Road a China crisis for North Sea main ports? in World Cargo News, 17. December 2019.

- ^Harry G. Broadman "Afrika´s Silk Road" (2007), pp 59.

- ^Button 2004

- ^abcdeButton 2004: 9

- ^abHindley 2004: 41.

- ^abcpipeline (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

- ^BP Caspian: Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline (Overview).

References

[edit]- Stearns, Peter N.;William L. Langer (2001).The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged.Houghton Mifflin Company.ISBN0-395-65237-5.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George (1916).Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times to the Fall of Rome.Cambridge University Press.

- Denemark, Robert Allen; el al. (2000).World System History: The Social Science of Long-Term Change.Routledge.ISBN0-415-23276-7.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011).China's Ancient Tea Horse Road.Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.ASINB005DQV7Q2

- Glasse, Cyril (2001).The New Encyclopedia of Islam.Rowman Altamira.ISBN0-7591-0190-6.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson(1994).Documentation for Ancient Arabia.Liverpool University Press.ISBN0-85323-359-4.

- Edwards, I. E. S.;Boardman, John;Bury, John B.;Cook, S.A. (1969).The Cambridge Ancient History.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-22717-8.

- Larsen, Curtis E. (1983).Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society.University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-46906-9.

- Eckenstein, Lina (2005).A History of Sinai.Adamant Media Corporation.ISBN0-543-95215-0.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994).Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1.University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-46731-7.

- Shaw, Ian(2003).The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-280458-8.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (2000).The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce.Berghahn Books.ISBN1-57181-221-0.

- Orlinsky, Harry Meyer (1981).Israel Exploration Journal Reader.KTAV Publishing House Inc.ISBN0-87068-267-9.

- Silver, Morris (1983).Prophets and Markets: The Political Economy of Ancient Israel.Springer.ISBN0-89838-112-6.

- Ball, Warwick(2000).Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire.Routledge.ISBN0-415-11376-8.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003).Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans.Diane Publishing Company.ISBN0-87169-248-1.

- Burns, Thomas Samuel (2003).Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.–A.D. 400.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN0-8018-7306-1.

- Seaman, Lewis Charles Bernard (1973).Victorian England: Aspects of English and Imperial History 1837-1901.Routledge.ISBN0-415-04576-2.

- Hindley, Brian (2004).Trade Liberalization in Aviation Services: Can the Doha Round Free Flight?.American Enterprise Institute.ISBN0-8447-7171-6.

- Dollinger, Philippe (1999).The German Hansa.Routledge.ISBN0-415-19072-X.

- "western Africa, history of".Encyclopædia Britannica.Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003).The Straits of Malacca: Gateway Or Gauntlet?.McGill-Queen's Press.ISBN0-7735-2515-7.

- Lindsay, W S (2006).History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce.Adamant Media Corporation.ISBN0-543-94253-8.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003).Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements.Le xing ton Books.ISBN0-7391-0407-1.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond; el al. (1984).Cross-Cultural Trade in World History.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-26931-8.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001).Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC–AD 305.Routledge.ISBN0-415-24219-3.

- Scarre, Chris (1995).The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome.Penguin Books.ISBN0-14-051329-9.

- Toutain, Jules (1979).The Economic Life of the Ancient World.Ayer Publishing.ISBN0-405-11578-4.

- Carter, Mia; Harlow, Barbara (2004).Archives of Empire: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal.Duke University Press.ISBN0-8223-3189-6.

- Major, John (1993).Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal, 1903–1979.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-52126-2.

- "Roman road system".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "wagon train".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "canal".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "roads and highways".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "automotive industry".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "truck".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "canals and inland waterways".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- "pipeline".Encyclopædia Britannica.2002.

- Button, Kenneth John (2004).Wings Across Europe: Towards An Efficient European Air Transport System.Ashgate Publishing.ISBN0-7546-4321-2.

- G. Schulze, Gunther; Ursprung, Heinrich W., eds. (2003).International Environmental Economics: A Survey of the Issues.US: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-926111-3.

- Krech III, Shepard; Merchant, Carolyn; McNeill, John Robert, eds. (2003).Encyclopedia of World Environmental History.US: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-93735-1.

- Schwela, Dietrich; Zali, Olivier (1998).Urban Traffic Pollution.Taylor & Francis, Inc.ISBN978-0-419-23720-4.

- Kearney, Milo (2003).The Indian Ocean in World History.Routledge.ISBN0-415-31277-9.

- Traderroute, Turkey (2023). TheTurkish import and exporter.İstanbulTrader Faulkner

External links

[edit]- Trade Routes: The Growth of Global Trade. ArchAtlas, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford.Archived22 April 2008 at theWayback Machine

- Ancient Trade Routes between Europe and Asia. Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art