Triceratops

| Triceratops Temporal range:Late Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal mount of aT. prorsusspecimen at theNatural History Museum of Los Angeles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Family: | †Ceratopsidae |

| Subfamily: | †Chasmosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Triceratopsini |

| Genus: | †Triceratops Marsh,1889b |

| Type species | |

| †Ceratops horridus Marsh, 1889a

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Triceratops(/traɪˈsɛrətɒps/try-SERR-ə-tops;[1]lit. 'three-horned face') is agenusofchasmosaurineceratopsiandinosaurthat lived during the lateMaastrichtianage of the LateCretaceousperiod,about 68 to 66million years agoin what is now western North America. It was one of the last-known non-avian dinosaurs and lived until theCretaceous–Paleogene extinction event66 million years ago. The nameTriceratops,which means 'three-horned face', is derived from theGreekwordstrí-(τρί-) meaning 'three',kéras(κέρας) meaning 'horn', andṓps(ὤψ) meaning 'face'.

Bearing a large bonyfrill,three horns on the skull, and a large, four-legged body, exhibitingconvergent evolutionwithbovinesandrhinoceroses,Triceratopsis one of the most recognizable of all dinosaurs and the best-known ceratopsian. It was also one of the largest, measuring around 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) long and weighing up to 6–10 metric tons (6.6–11.0 short tons). It shared the landscape with and was most likely preyed upon byTyrannosaurus,though it is less certain that two adults would battle in the fanciful manner often depicted in museum displays and popular media. The functions of the frills and three distinctive facial horns on its head have inspired countless debates. Traditionally, these have been viewed as defensive weapons against predators. More recent interpretations find it probable that these features were primarily used in species identification, courtship, and dominance display, much like the antlers and horns of modernungulates.

Triceratopswas traditionally placed within the "short-frilled" ceratopsids, but moderncladisticstudies show it to be a member ofChasmosaurinae,which usually have long frills. Twospecies,T. horridusandT. prorsus,are considered valid today. Seventeen different species, however, have been named throughout history. Research published in 2010 concluded that the contemporaneousTorosaurus,a ceratopsid long regarded as a separate genus, representsTriceratopsin its mature form. This view has still been highly disputed and much more data is needed to settle this ongoing debate.

Triceratopshas been documented by numerous remains collected since the genus was first described in 1889 by American paleontologistOthniel Charles Marsh.Specimens representing life stages from hatchling to adult have been found. As thearchetypalceratopsian,Triceratopsis one of the most beloved, popular dinosaurs and has been featured in numerous films, postage stamps, and many other types of media.[2]

Discovery and identification[edit]

The first namedfossilspecimen now attributed toTriceratopsis a pair of brow horns attached to a skull roof that were found by George Lyman Cannon nearDenver,Colorado,in the spring of 1887.[3]This specimen was sent toOthniel Charles Marsh,who believed that theformationfrom which it came from dated from thePlioceneand that the bones belonged to a particularly large and unusualbison,which he namedBison alticornis.[3][4]He realized that there were horned dinosaurs by the next year, which saw his publication of the genusCeratopsfrom fragmentary remains,[5]but he still believedB. alticornisto be a Pliocenemammal.It took a third and much more complete skull to fully change his mind.

Although not confidentially assignable, fossils possibly belonging toTriceratopswere described as two taxa,Agathaumas sylvestrisandPolyonax mortuarius,in 1872 and 1874, respectively, by Marsh's archrivalEdward Drinker Cope.[6][7]Agathaumaswas named based on a pelvis, several vertebrae, and a few ribs collected byFielding Bradford Meekand Henry Martyn Bannister near theGreen Riverof southeasternWyomingfrom layers coming from the MaastrichtianLance Formation.[8]Due to the fragmentary nature of the remains, it can only confidently be assigned to Ceratopsidae.[9][10]Polyonax mortuariuswas collected by Cope himself in 1873 from northeastern Colorado, possibly coming from the MaastrichtianDenver Formation.[11][7]The fossils only consisted of fragmentary horn cores, 3 dorsal vertebrae, and fragmentary limb elements.[7]Polyonaxhas the same issue asAgathaumas,with the fragmentary remains non-assignable beyond Ceratopsidae.[12][9]

TheTriceratopsholotype,YPM 1820, was collected in 1888 from theLance Formationof Wyoming by fossil hunterJohn Bell Hatcher,but Marsh initially described this specimen as another species ofCeratops.[13]Cowboy Edmund B. Wilson had been startled by the sight of a monstrous skull poking out of the side of a ravine. He tried to recover it by throwing a lasso around one of the horns. When it broke off, the skull tumbling to the bottom of the cleft, Wilson brought the horn to his Boss. His Boss was rancher and avid fossil collector Charles Arthur Guernsey, who just so happened to show it to Hatcher. Marsh subsequently ordered Hatcher to locate and salvage the skull.[9]The holotype was first namedCeratops horridus.When further preparation uncovered the third nose horn, Marsh changed his mind and gave the piece the new generic nameTriceratops(lit. 'three horn face'), accepting hisBison alticornisas another species ofCeratops.[14]It would, however, later be added toTriceratops.[15]The sturdy nature of the animal's skull has ensured that many examples have been preserved as fossils, allowing variations between species and individuals to be studied.Triceratopsremains have subsequently been found inMontanaandSouth Dakota(and more in Colorado and Wyoming), as well as the Canadian provinces ofSaskatchewanandAlberta.

Species[edit]

AfterTriceratopswas described, between 1889 and 1891, Hatcher collected another thirty-one of its skulls with great effort. The first species had been namedT. horridusby Marsh. Itsspecific namewas derived from the Latin wordhorridusmeaning "rough" or "rugose", perhaps referring to the type specimen's rough texture, later identified as an aged individual. The additional skulls varied to a lesser or greater degree from the original holotype. This variation is unsurprising, given thatTriceratopsskulls are large three-dimensional objects from individuals of different ages and both sexes that which were subjected to different amounts and directions of pressure during fossilization.[9]

In the first attempt to understand the many species,Richard Swann Lullfound two groups, although he did not say how he distinguished them. One group composed ofT. horridus,T. prorsus,andT. brevicornus('the short-horned'). The other composed ofT. elatusandT. calicornis.Two species (T. serratusandT. flabellatus) stood apart from these groups.[15]By 1933, alongside his revision of the landmark 1907 Hatcher–Marsh–Lullmonographof all known ceratopsians, he retained his two groups and two unaffiliated species, with a third lineage ofT. obtususandT. hatcheri('Hatcher's') that was characterized by a very small nasal horn.[10]T. horridus–T. prorsus–T. brevicornuswas now thought to be the most conservative lineage, with an increase in skull size and a decrease in nasal horn size.T. elatus–T. calicorniswas defined by having large brow horns and small nasal horns.[10][16]Charles Mortram Sternbergmade one modification by addingT. eurycephalus('the wide-headed') and suggesting that it linked the second and third lineages closer together than they were to theT. horriduslineage.[17]

With time, the idea that the differing skulls might be representative of individual variation within one (or two) species gained popularity. In 1986,John OstromandPeter Wellnhoferpublished a paper in which they proposed that there was only one species,Triceratops horridus.[18]Part of their rationale was that there are generally only one or two species of any large animal in a region. To their findings, Thomas Lehman added the old Lull–Sternberg lineages combined with maturity andsexual dimorphism,suggesting that theT. horridus–T. prorsus–T. brevicornuslineage was composed of females, theT. calicornis–T. elatuslineage was made up of males, and theT. obtusus–T. hatcherilineage was of pathologic old males.[19]

These findings were contested a few years later by paleontologistCatherine Forster,who reanalyzedTriceratopsmaterial more comprehensively and concluded that the remains fell into two species,T. horridusandT. prorsus,although the distinctive skull ofT.( "Nedoceratops")hatcheridiffered enough to warrant a separate genus.[20]She found thatT. horridusand several other species belonged together and thatT. prorsusandT. brevicornusstood alone. Since there were many more specimens in the first group, she suggested that this meant the two groups were two species. It is still possible to interpret the differences as representing a single species with sexual dimorphism.[9][21]

In 2009, John Scannella and Denver Fowler supported the separation ofT. prorsusandT. horridus,noting that the two species are also separated stratigraphically within the Hell Creek Formation, indicating that they did not live together at the same time.[22]

Valid species[edit]

- T. horridus(Marsh, 1889) Marsh, 1889 (originallyCeratops)(type species)

- T. prorsusMarsh, 1890

Synonyms and doubtful species[edit]

Some of the following species aresynonyms,as indicated in parentheses ( "=T. horridus"or" =T. prorsus"). All the others are each considered anomen dubium(lit. 'dubious name') because they are based on remains too poor or incomplete to be distinguished from pre-existingTriceratopsspecies.

- T. albertensisC. M. Sternberg,1949

- T. alticornis(Marsh 1887)Hatcher,Marsh,andLull,1907 [originallyBisonalticornis,Marsh 1887, andCeratopsalticornis,Marsh 1888]

- T. brevicornusHatcher, 1905(=T. prorsus)

- T. calicornisMarsh, 1898(=T. horridus)

- T. elatusMarsh, 1891(=T. horridus)

- T. eurycephalusSchlaikjer,1935

- T. flabellatusMarsh, 1889(=SterrholophusMarsh, 1891) (=T. horridus)

- T. galeusMarsh, 1889

- T. hatcheri(Hatcher & Lull 1905) Lull, 1933(contentious; seeNedoceratopsbelow)

- T. ingensMarsh videLull,1915

- T. maximusBrown,1933

- T. mortuarius(Cope,1874) Kuhn, 1936(nomen dubium;originallyPolyonax mortuarius)

- T. obtususMarsh, 1898(=T. horridus)

- T. serratusMarsh, 1890(=T. horridus)

- T. sulcatusMarsh, 1890

- T. sylvestris(Cope, 1872) Kuhn, 1936(nomen dubium;originallyAgathaumas sylvestris)

Description[edit]

Size[edit]

Triceratopswas a very large animal, measuring around 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) in length and weighing up to 6–10 metric tons (6.6–11.0 short tons).[23][24][25]A specimen ofT. horridusnamed Kelsey measured 6.7–7.3 meters (22–24 ft) long, has a 2-meter (6.5 ft) skull, stood about 2.3 meters (7.5 ft) tall, and was estimated by theBlack Hills Instituteto weigh approximately 5.4 metric tons (6.0 short tons).[26][27]

Skull[edit]

Like allchasmosaurines,Triceratopshad a large skull relative to its body size, among the largest of all land animals. The largest-known skull, specimenMWC7584 (formerlyBYU12183), is estimated to have been 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) in length when complete[28]and could reach almost a third of the length of the entire animal.[29]

The front of the head was equipped with a large beak in front of its teeth. The core of the top beak was formed by a special rostral bone. Behind it, thepremaxillaebones were located, embayed from behind by very large, circular nostrils. In chasmosaurines, the premaxillae met on their midline in a complex bone plate, the rear edge of which was reinforced by the "narial strut". From the base of this strut, a triangular process jutted out into the nostril.Triceratopsdiffers from most relatives in that this process was hollowed out on the outer side. Behind the toothless premaxilla, themaxillabore thirty-six to forty tooth positions, in which three to five teeth per position were vertically stacked. The teeth were closely appressed, forming a "dental battery" curving to the inside. The skull bore a single horn on the snout above the nostrils. InTriceratops,the nose horn is sometimes recognisable as a separate ossification, the epinasal.[30]

The skull also featured a pair of supraorbital "brow" horns approximately 1 meter (3.3 ft) long, with one above each eye.[31][32]Thejugal bonespointed downward at the rear sides of the skull and were capped by separate epijugals. WithTriceratops,these were not particularly large and sometimes touched the quadratojugals. The bones of the skull roof were fused and by a folding of thefrontal bones,a "double" skull roof was created. InTriceratops,some specimens show afontanelle,an opening in the upper roof layer. The cavity between the layers invaded the bone cores of the brow horns.[30]

At the rear of the skull, the outersquamosal bonesand the innerparietal bonesgrew into a relatively short, bony frill, adorned withepoccipitalsin young specimens. These were low triangular processes on the frill edge, representing separate skin ossifications orosteoderms.Typically, withTriceratopsspecimens, there are two epoccipitals present on each parietal bone, with an additional central process on their border. Each squamosal bone had five processes. Most other ceratopsids had large parietalfenestrae,openings in their frills, but those ofTriceratopswere noticeably solid,[33]unless the genusTorosaurusrepresents matureTriceratopsindividuals, which it most likely does not. Under the frill, at the rear of the skull, a hugeoccipital condyle,up to 106 millimeters (4.2 in) in diameter, connected the head to the neck.[30]

The lower jaws were elongated and met at their tips in a shared epidentary bone, the core of the toothless lower beak. In the dentary bone, the tooth battery curved to the outside to meet the battery of the upper jaw. At the rear of the lower jaw, thearticular bonewas exceptionally wide, matching the general width of the jaw joint.[30]T. horriduscan be distinguished fromT. prorsusby having a shallower snout.[23]

Postcranial skeleton[edit]

Chasmosaurines showed little variation in their postcranial skeleton.[30]The skeleton ofTriceratopsis markedly robust. BothTriceratopsspecies possessed a very sturdy build, with strong limbs, short hands with three hooves each, and short feet with four hooves each.[34]Thevertebral columnconsisted of ten neck, twelve back, ten sacral, and about forty-five tailvertebrae.The front neck vertebrae were fused into a syncervical. Traditionally, this was assumed to have incorporated the first three vertebrae, thus implying that the frontmostatlaswas very large and sported a neural spine. Later interpretations revived an old hypothesis byJohn Bell Hatcherthat, at the very front, a vestige of the real atlas can be observed, the syncervical then consisting of four vertebrae. The vertebral count mentioned is adjusted to this view. InTriceratops,the neural spines of the neck are constant in height and don't gradually slope upwards. Another peculiarity is that the neck ribs only begin to lengthen with the ninth cervical vertebra.[30]

The rather short and high vertebrae of the back were, in its middle region, reinforced by ossified tendons running along the tops of theneural arches.The straight sacrum was long and adult individuals show a fusion of all sacral vertebrae. InTriceratopsthe first four and last two sacrals had transverse processes, connecting the vertebral column to the pelvis, that were fused at their distal ends. Sacrals seven and eight had longer processes, causing the sacrum to have an oval profile in top view. On top of the sacrum, a neural plate was present formed by a fusion of the neural spines of the second through fifth vertebrae.Triceratopshad a large pelvis with a longilium.Theischiumwas curved downwards. The foot was short with four functional toes. The phalangeal formula of the foot is 2-3-4-5-0.[30]

Although certainlyquadrupedal,the posture of horned dinosaurs has long been the subject of some debate. Originally, it was believed that the front legs of the animal had to besprawlingat a considerable angle from thethoraxin order to better bear the weight of the head.[9]This stance can be seen in paintings byCharles KnightandRudolph Zallinger.Ichnologicalevidence in the form oftrackwaysfrom horned dinosaurs and recent reconstructions of skeletons (both physical and digital) seem to show thatTriceratopsand other ceratopsids maintained an upright stance during normal locomotion, with the elbows flexed to behind and slightly bowed out, in an intermediate state between fully upright and fully sprawling, comparable to the modern rhinoceros.[34][35][36][37]

The hands and forearms ofTriceratopsretained a fairly primitive structure when compared to other quadrupedal dinosaurs, such asthyreophoransand manysauropods.In those two groups, the forelimbs of quadrupedal species were usually rotated so that the hands faced forward with palms backward ( "pronated" ) as the animals walked.Triceratops,like other ceratopsians and related quadrupedalornithopods(together forming theCerapoda), walked with most of their fingers pointing out and away from the body, the original condition for dinosaurs. This was also retained by bipedal forms, liketheropods.InTriceratops,the weight of the body was carried by only the first three fingers of the hand, while digits 4 and 5 were vestigial and lacked claws or hooves.[34]The phalangeal formula of the hand is 2-3-4-3-1, meaning that the first or innermost finger of the forelimb has two bones, the next has three, the next has four, etc.[38]

Skin[edit]

Preserved skin fromTriceratopsis known. This skin consist of large scales, some of which exceed 100 millimetres (3.9 in) across, which have conical projections rising from their center. A preserved piece of skin from the frill of a specimen is also known, which consists of small polygonal basement scales.[39]

Classification[edit]

Triceratopsis the best-known genus ofCeratopsidae,a family of large, mostly North Americanceratopsians.The exact relationship ofTriceratopsamong the other ceratopsids has been debated over the years. Confusion stemmed mainly from the combination of a short, solid frill (similar to that ofCentrosaurinae), with long brow horns (more akin toChasmosaurinae).[40]In the first overview of ceratopsians,R. S. Lullhypothesized the existence of two lineages, one ofMonocloniusandCentrosaurusleading toTriceratops,the other withCeratopsandTorosaurus,makingTriceratopsa centrosaurine as the group is understood today.[15]Later revisions supported this view whenLawrence Lambe,in 1915, formally describing the first, short-frilled group as Centrosaurinae (includingTriceratops), and the second, long-frilled group as Chasmosaurinae.[10][41]

In 1949,Charles Mortram Sternbergwas the first to question this position, proposing instead thatTriceratopswas more closely related toArrhinoceratopsandChasmosaurusbased on skull and horn features, makingTriceratopsa chasmosaurine ( "ceratopsine" in his usage) genus.[17]He was largely ignored, withJohn Ostrom[42]and later David Norman placingTriceratopswithin the Centrosaurinae.[43]

Subsequent discoveries and analyses, however, proved the correctness of Sternberg's view on the position ofTriceratops,with Thomas Lehman defining both subfamilies in 1990 and diagnosingTriceratopsas "ceratopsine" on the basis of several morphological features. Apart from the one feature of a shortened frill,Triceratopsshares no derived traits with centrosaurines.[19]Further research byPeter Dodson,including a 1990cladisticanalysis and a 1993 study using resistant-fit theta-rho analysis, or RFTRA (amorphometric techniquewhich systematically measures similarities in skull shape), reinforcesTriceratops'placement as a chasmosaurine.[44][45]

The cladogram below follows Longrich (2014), who named a new species ofPentaceratops,and included nearly all species of chasmosaurine.[46]

| Chasmosaurinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For many years after its discovery, the deeper evolutionary origins ofTriceratopsand its close relatives remained largely obscure. In 1922, the newly discoveredProtoceratopswas seen as its ancestor byHenry Fairfield Osborn,[9]but many decades passed before additional findings came to light. Recent years have been fruitful for the discovery of several antecedents ofTriceratops.Zuniceratops,the earliest-known ceratopsian with brow horns, was described in the late 1990s, andYinlong,the first knownJurassicceratopsian, was described in 2005.

These new finds have been vital in illustrating the origins of ceratopsians in general, suggesting an Asian origin in the Jurassic and the appearance of truly horned ceratopsians by the beginning of the Late Cretaceous in North America.[30]

Inphylogenetic taxonomy,the genusTriceratopshas been used as a reference point in the definition of Dinosauria. Dinosaurs have been designated as all descendants of themost recent common ancestorofTriceratopsandmodern birds.[47]Furthermore,Ornithischiahas been defined as those dinosaurs more closely related toTriceratopsthan to modern birds.[48]

Paleobiology[edit]

AlthoughTriceratopsis commonly portrayed as aherdinganimal, there is currently little evidence to suggest that they lived in herds. While several other ceratopsians are known frombone bedspreserving bones from two to hundreds or even thousands of individuals, there is currently only one documented bonebed dominated byTriceratopsbones: a site in southeastern Montana with the remains of three juveniles. It may be significant that only juveniles were present.[49]In 2012, a group of threeTriceratopsin relatively complete condition, each of varying sizes from a full-grown adult to a small juvenile, were found nearNewcastle, Wyoming.The remains are currently under excavation by paleontologist Peter Larson and a team from theBlack Hills Institute.It is believed that the animals were traveling as a family unit, but it remains unknown if the group consists of a mated pair and their offspring, or two females and a juvenile they were caring for. The remains also show signs of predation or scavenging fromTyrannosaurus,particularly on the largest specimen, with the bones of the front limbs showing breakage and puncture wounds fromTyrannosaurusteeth.[50]In 2020, Illies and Fowler described theco-ossifieddistal caudal vertebrae ofTriceratops.According to them, this pathology could have arisen after oneTriceratopsaccidentally stepped on the tail of another member of the herd.[51][52]

For many years,Triceratopsfinds were known only from solitary individuals.[49]These remains are very common. For example,Bruce Erickson,a paleontologist of theScience Museum of Minnesota,has reported having seen 200 specimens ofT. prorsusin theHell Creek FormationofMontana.[53]Similarly,Barnum Brownclaimed to have seen over 500 skulls in the field.[9]: 79 BecauseTriceratopsteeth, horn fragments, frill fragments, and other skull fragments are such abundant fossils in theLancian faunal stageof the lateMaastrichtian(Late Cretaceous,66 mya) of western North America, it is regarded as one of the dominant herbivores of the time, if not the most dominant. In 1986,Robert Bakkerestimated it as making up five sixths of the large dinosaur fauna at the end of the Cretaceous.[54]Unlike most animals, skull fossils are far more common thanpostcranialbones forTriceratops,suggesting that the skull had an unusually highpreservation potential.[55]

Analysis of the endocranial anatomy ofTriceratopssuggest its sense of smell was poor compared to that of other dinosaurs. Its ears were attuned to low frequency sounds, given the short cochlear lengths recorded in an analysis by Sakagamiet al,.This same study also suggests thatTriceratopsheld its head about 45 degrees to the ground, an angle which would showcase the horns and frill most effectively that simultaneously allowed the animal to take advantage of food through grazing.[56]

A 2022 study by Wiemann and colleagues of various dinosaur genera, includingTriceratops,suggests that it had anectothermic(cold blooded) orgigantothermicmetabolism, on par with that of modern reptiles. This was uncovered using thespectroscopyof lipoxidation signals, which are byproducts ofoxidative phosphorylationand correlate with metabolic rates. They suggested that such metabolisms may have been common for ornithischian dinosaurs in general, with the group evolving towards ectothermy from an ancestor with anendothermic(warm blooded) metabolism.[57]

Dentition and diet[edit]

Triceratopswereherbivorousand, because of their low slung head, their primary food was probably low growing vegetation, although they may have been able to knock down taller plants with their horns,beak,and sheer bulk.[30][58]The jaws were tipped with a deep, narrow beak, believed to have been better at grasping and plucking than biting.[42]

Triceratopsteeth were arranged in groups called batteries, which contained 36 to 40 tooth columns in each side of each jaw and 3 to 5 stacked teeth per column, depending on the size of the animal.[30]This gives a range of 432 to 800 teeth, of which only a fraction were in use at any given time (as tooth replacement was continuous throughout the life of the animal).[30]They functioned by shearing in a vertical to near-vertical orientation.[30]The great size and numerous teeth ofTriceratopssuggests that they ate large volumes of fibrous plant material. Some researchers suggest it atepalmsandcycads[59][60]and others suggest it ateferns,which then grew in prairies.[61]

Functions of the horns and frill[edit]

There has been much speculation over the functions ofTriceratops'head adornments. The two main theories have revolved around use in combat and in courtship display, with the latter now thought to be the most likely primary function.[30]

Early on, Lull postulated that the frills may have served as anchor points for the jaw muscles to aid chewing by allowing increased size and power for the muscles.[62]This has been put forward by other authors over the years, but later studies do not find evidence of large muscle attachments on the frill bones.[63]

Triceratopswere long thought to have used their horns and frills in combat with large predators, such asTyrannosaurus,the idea being discussed first byCharles H. Sternbergin 1917 and 70 years later by Robert Bakker.[54][64]There is evidence thatTyrannosaurusdid have aggressive head-on encounters withTriceratops,based on partially healed tyrannosaur tooth marks on aTriceratopsbrow horn andsquamosal.The bitten horn is also broken, with new bone growth after the break. Which animal was the aggressor, however, is unknown.[65]Paleontologist Peter Dodson estimates that, in a battle against a bullTyrannosaurus,theTriceratopshad the upper hand and would successfully defend itself by inflicting fatal wounds to theTyrannosaurususing its sharp horns.Tyrannosaurusis also known to have fed onTriceratops,as shown by a heavily tooth-scoredTriceratopsiliumandsacrum.[66]

In addition to combat with predators using its horns,Triceratopsare popularly shown engaging each other in combat with horns locked. While studies show that such activity would be feasible, if unlike that of present-day horned animals,[67]there is disagreement about whether they did so. Although pitting, holes, lesions, and other damage onTriceratopsskulls (and the skulls of other ceratopsids) are often attributed to horn damage in combat, a 2006 study finds no evidence for horn thrust injuries causing these forms of damage (with there being no evidence of infection or healing). Instead, non-pathologicalbone resorption,or unknown bone diseases, are suggested as causes.[68]A newer study compared incidence rates of skull lesions andperiosteal reactioninTriceratopsandCentrosaurus,showing that these were consistent withTriceratopsusing its horns in combat and the frill being adapted as a protective structure, while lower pathology rates inCentrosaurusmay indicate visual use over physical use of cranial ornamentation or a form of combat focused on the body rather than the head.[69]The frequency of injury was found to be 14% inTriceratops.[70]The researchers also concluded that the damage found on the specimens in the study was often too localized to be caused by bone disease.[71]Histological examination reveals that the frill ofTriceratopsis composed of fibrolamellar bone.[72]This containsfibroblaststhat play a critical role in wound healing and is capable of rapidly depositing bone during remodeling.[73][74]

One skull was found with a hole in thejugal bone,apparently a puncture wound sustained while the animal was alive, as indicated by signs of healing. The hole has a diameter close to that of the distal end of aTriceratopshorn. This and other apparent healed wounds in the skulls of ceratopsians has been cited as evidence of non-fatal intraspecific competition in these dinosaurs.[75][76]Another specimen, referred to as "Big John", has a similar fenestra to the squamosal caused by what appears to be anotherTriceratopshorn and the squamosal bone shows signs of significant healing, further vindicating the hypothesis that this ceratopsian used its horns for intra-specific combat.[77]

The large frill also may have helped to increase body area toregulate body temperature.[78]A similar theory has been proposed regarding the plates ofStegosaurus,[79]although this use alone would not account for the bizarre and extravagant variation seen in different members ofCeratopsidae,which would rather support the sexual display theory.[30]

The theory that frills functioned as a sexual display was first proposed by Davitashvili in 1961 and has gained increasing acceptance since.[19][63][80]Evidence that visual display was important, either in courtship or other social behavior, can be seen in the ceratopsians differing markedly in their adornments, making each species highly distinctive. Also, modern living creatures with such displays of horns and adornments use them similarly.[75]A 2006 study of the smallestTriceratopsskull, ascertained to be a juvenile, shows the frill and horns developed at a very early age, predating sexual development and probably important for visual communication and species recognition in general.[81]The use of the exaggerated structures to enable dinosaurs to recognize their own species has been questioned, as no such function exists for such structures in modern species.[82]

Growth and ontogeny[edit]

In 2006, the first extensive ontogenetic study ofTriceratopswas published in the journalProceedings of the Royal Society.The study, byJohn R. Hornerand Mark Goodwin, found that individuals ofTriceratopscould be divided into four general ontogenetic groups: babies, juveniles, subadults, and adults. With a total number of 28 skulls studied, the youngest was only 38 centimeters (15 in) long. Ten of the 28 skulls could be placed in order in a growth series with one representing each age. Each of the four growth stages were found to have identifying features. Multiple ontogenetic trends were discovered, including the size reduction of the epoccipitals, development and reorientation of postorbital horns, and hollowing out of the horns.[83]

Torosaurusas growth stage ofTriceratops[edit]

Torosaurusis a ceratopsid genus first identified from a pair of skulls in 1891, two years after the identification ofTriceratopsby Othneil Charles Marsh. The genusTorosaurusresemblesTriceratopsin geological age, distribution, anatomy, and size, so it has been recognised as a close relative.[84]Its distinguishing features are an elongated skull and the presence of two ovular fenestrae in the frill. Paleontologists investigating dinosaurontogenyin Montana'sHell Creek Formationhave recently presented evidence that the two represent a single genus.

John Scannella, in a paper presented inBristolat the conference of theSociety of Vertebrate Paleontology(September 25, 2009), reclassifiedTorosaurusas especially matureTriceratopsindividuals, perhaps representing a single sex. Horner, Scannella's mentor at Bozeman Campus,Montana State University,noted that ceratopsian skulls consist of metaplastic bone. A characteristic of metaplastic bone is that it lengthens and shortens over time, extending and resorbing to form new shapes. Significant variety is seen even in those skulls already identified asTriceratops,Horner said, "where the horn orientation is backwards in juveniles and forward in adults". Approximately 50% of all subadultTriceratopsskulls have two thin areas in the frill that correspond with the placement of "holes" inTorosaurusskulls, suggesting that holes developed to offset the weight that would otherwise have been added as maturingTriceratopsindividuals grew longer frills.[85]A paper describing these findings in detail was published in July 2010 by Scannella and Horner. It formally argues thatTorosaurusand the similar contemporaryNedoceratopsare synonymous withTriceratops.[28]

The assertion has since ignited much debate. Andrew Farke had, in 2006, stressed that no systematic differences could be found betweenTorosaurusandTriceratops,apart from the frill.[84]He nevertheless disputed Scannella's conclusion by arguing in 2011 that the proposed morphological changes required to "age" aTriceratopsinto aTorosauruswould be without precedent among ceratopsids. Such changes would include the growth of additionalepoccipitals,reversion of bone texture from an adult to immature type and back to adult again, and growth of frill holes at a later stage than usual.[86]A study by Nicholas Longrich and Daniel Field analyzed 35 specimens of bothTriceratopsandTorosaurus.The authors concluded thatTriceratopsindividuals too old to be considered immature forms are represented in the fossil record, as areTorosaurusindividuals too young to be considered fully mature adults. The synonymy ofTriceratopsandTorosauruscannot be supported, they said, without more convincing intermediate forms than Scannella and Horner initially produced. Scannella'sTriceratopsspecimen with a hole on its frill, they argued, could represent a diseased or malformed individual rather than a transitional stage between an immatureTriceratopsand matureTorosaurusform.[87][88]

Other genera as growth stages ofTriceratops[edit]

Opinion has varied on the validity of a separate genus forNedoceratops.Scannella and Horner regarded it as an intermediate growth stage betweenTriceratopsandTorosaurus.[28][89]Farke, in his 2011 redescription of the only known skull, concluded that it was an aged individual of its own validtaxon,Nedoceratops hatcheri.[86]Longrich and Fields also did not consider it a transition betweenTorosaurusandTriceratops,suggesting that the frill holes were pathological.[88]

As described above, Scannella had argued in 2010 thatNedoceratopsshould be considered a synonym ofTriceratops.[28]Farke (2011) maintained that it represents a valid distinct genus.[86]Longrich agreed with Scannella aboutNedoceratopsand made a further suggestion that the recently describedOjoceratopswas likewise a synonym. The fossils, he argued, are indistinguishable from theTriceratops horridusspecimens that were previously attributed to the defunct speciesTriceratops serratus.

Longrich observed that another newly described genus,Tatankaceratops,displayed a strange mix of characteristics already found in adult and juvenileTriceratops.Rather than representing a distinct genus,Tatankaceratopscould as easily represent a dwarfTriceratopsor aTriceratopsindividual with a developmental disorder that caused it to stop growing prematurely.[90]

Paleoecology[edit]

Triceratopslived during the Late Cretaceous of western North America, its fossils coming from theEvanston Formation,Scollard Formation,Laramie Formation,Lance Formation,Denver Formation,andHell Creek Formation.[91]These fossil formations date back to the time of theCretaceous–Paleogene extinction event,which has been dated to 66 ± 0.07 million years ago.[92]Many animals and plants have been found in these formations, but mostly from the Lance Formation and Hell Creek Formation.[91]Triceratopswas one of the last ceratopsian genera to appear before the end of the Mesozoic. The relatedTorosaurusand more distantly related diminutiveLeptoceratopswere also present, though their remains have been rarely encountered.[9]

Theropods from these formations include genera ofdromaeosaurids,tyrannosaurids,ornithomimids,troodontids,[91]avialans,[93]andcaenagnathids.[94]Dromaeosaurids from the Hell Creek Formation areAcheroraptorandDakotaraptor.Indeterminate dromaeosaurs are known from other fossil formations. Common teeth previously referred toDromaeosaurusandSaurornitholesteswere considered to be those ofAcheroraptor.[95]The tyrannosaurids from the formation areNanotyrannusandTyrannosaurus,although the former is most likely a junior synonym of the latter. Among ornithomimids are the generaStruthiomimusandOrnithomimus.[91]An undescribed animal named "Orcomimus"could be from the formation.[96]Troodontids are only represented byPectinodonandParonychodonin the Hell Creek Formation with a possible species ofTroodonfrom the Lance Formation. One species of unknowncoelurosauris known from teeth in the Hell Creek and similar formations by a single species,Richardoestesia.Only threeoviraptorosaursare from the Hell Creek Formation:Anzu,Leptorhynchos[94]and a giant species of caenagnathid, very similar toGigantoraptor,from South Dakota. However, only fossilized foot prints were discovered.[97]The avialans known from the formation areAvisaurus,[91]multiple species ofBrodavis,[98]and several other species ofhesperornithoforms,as well as several species of truebirds,includingCimolopteryx.[93]

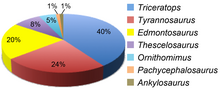

Ornithischiansare abundant in the Scollard, Laramie, Lance, Denver, and Hell Creek Formation. The main groups of ornithischians areankylosaurians,ornithopods,ceratopsians,andpachycephalosaurians.Three ankylosaurians are known:Ankylosaurus,Denversaurus,and possibly a species ofEdmontoniaor an undescribed genus. Multiple genera of ceratopsians are known from the formation other thanTriceratops.These include theleptoceratopsidLeptoceratopsand thechasmosaurineceratopsidsTorosaurus,[91]Nedoceratops,andTatankaceratops.[99]Ornithopods are common in the Hell Creek Formation and are known from several species of thethescelosaurineThescelosaurusand thehadrosauridEdmontosaurus.[91][100]Severalpachycephalosaurianshave been found in the Hell Creek Formation and in similar formations. Among them are the derivedpachycephalosauridsStygimoloch,[91]Dracorex,[101]Pachycephalosaurus,[91]Sphaerotholus,and an undescribed specimen from North Dakota. The first two might be junior synonyms ofPachycephalosaurus.

Mammalsare plentiful in the Hell Creek Formation. Groups represented includemultituberculates,metatherians,andeutherians.The multituberculates represented includeParacimexomys,[102]thecimolomyidsParessonodon,[103]Meniscoessus,Essonodon,Cimolomys,Cimolodon,andCimexomys,and theneoplagiaulacidsMesodmaandNeoplagiaulax.The metatherians are represented by theAlpha dontidsAlphadon,Protalphodon,andTurgidodon,thepediomyidsPediomys,[102]Protolambda,andLeptalestes,[104]thestagodontidDidelphodon,[102]thedeltatheridiidNanocuris,theherpetotheriidNortedelphys,[103]and theglasbiidGlasbius.A few eutherians are known, being represented byAlostera,[102]Protungulatum,[104]thecimolestidsCimolestesandBatodon,thegypsonictopsidGypsonictops,and the possiblenyctitheriidParanyctoides.[102]

Cultural significance[edit]

Triceratopsis the officialstate fossilofSouth Dakota.[105]It is also the official state dinosaur ofWyoming.[106]In 1942,Charles R. Knightpainted a mural incorporating a confrontation between aTyrannosaurusand aTriceratopsin theField Museum of Natural Historyfor theNational Geographic Society,establishing them as enemies in the popular imagination.[107]PaleontologistRobert Bakkersaid of the imagined rivalry betweenTyrannosaurusandTriceratops,"No matchup between predator and prey has ever been more dramatic. It's somehow fitting that those two massive antagonists lived out their co-evolutionary belligerence through thelast daysof thelast epochof theAge of Dinosaurs."[107]

References[edit]

- ^"Definition of triceratops | Dictionary".dictionary.RetrievedSeptember 30,2022.

- ^"Melbourne Museum acquires world's most complete triceratops skeleton in 'immense' dinosaur deal".the Guardian.December 2, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

- ^abCarpenter, K. (2006). "Bison"alticornisand O.C. Marsh's early views on ceratopsians ". In Carpenter, K. (ed.).Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs.Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 349–364.ISBN978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^Marsh, O.C. (1887)."Notice of new fossil mammals".American Journal of Science.34(202): 323–331.Bibcode:1887AmJS...34..323M.doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-34.202.323.S2CID129984410.Archivedfrom the original on September 29, 2018.RetrievedOctober 19,2021.

- ^Marsh, O.C. (1888)."A new family of horned Dinosauria, from the Cretaceous".American Journal of Science.36(216): 477–478.Bibcode:1888AmJS...36..477M.doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-36.216.477.S2CID130243398.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2020.RetrievedOctober 19,2021.

- ^Cope, E.D. (1872). "On the existence of Dinosauria in the Transition Beds of Wyoming".Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.12:481–483.

- ^abcCope, E.D. (1874). Report on the stratigraphy and Pliocene vertebrate paleontology of northern Colorado. Bulletin of the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories.9:9-28.

- ^Lull, R. S.,& Wright, N. E. (1942). Hadrosaurian dinosaurs of North America(Vol. 40). Geological Society of America.

- ^abcdefghiDodson, P. (1996).The Horned Dinosaurs.Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0-691-02882-8.

- ^abcdLull, R. S. (1933)."A revision of the Ceratopsia or horned dinosaurs".Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Natural History.3(3): 1–175.doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5716.RetrievedNovember 20,2010.

- ^"Division of Paleontology".research.amnh.org.RetrievedApril 12,2022.

- ^Dodson, P.; Forster, C.A.; Sampson, S.D. (2004). "Ceratopsidae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmo´lska, Halszka (eds.).The dinosauria.Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. pp. 494–513.ISBN978-0-520-94143-4.OCLC801843269..

- ^Marsh, O.C. (1889a)."Notice of new American Dinosauria".American Journal of Science.37(220): 331–336.Bibcode:1889AmJS...37..331M.doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-37.220.331.S2CID131729220.Archivedfrom the original on September 29, 2018.RetrievedOctober 19,2021.

- ^Marsh, O.C. (1889b)."Notice of gigantic horned Dinosauria from the Cretaceous".American Journal of Science.38(224): 173–175.Bibcode:1889AmJS...38..173M.doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-38.224.173.S2CID131187857.Archivedfrom the original on September 28, 2018.RetrievedOctober 19,2021.

- ^abcHatcher, J. B.; Marsh, O. C.; Lull, R. S. (1907).The Ceratopsia.Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.ISBN978-0-405-12713-7.

- ^Goussard, Florent (2006)."The skull of Triceratops in the palaeontology gallery, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris".Geodiversitas.28(3): 467–476.Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021.RetrievedDecember 22,2017– via ResearchGate.

- ^abSternberg, C. M. (1949). "The Edmonton fauna and description of a newTriceratopsfrom the Upper Edmonton member; phylogeny of the Ceratopsidae ".National Museum of Canada Bulletin.113:33–46.

- ^Ostrom, J. H.; Wellnhofer, P. (1986). "The Munich specimen ofTriceratopswith a revision of the genus ".Zitteliana.14:111–158.

- ^abcLehman, T. M. (1990). "The ceratopsian subfamily Chasmosaurinae: sexual dimorphism and systematics". In Carpenter, K.; Currie, P. J. (eds.).Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–229.ISBN978-0-521-36672-4.

- ^Forster, C.A. (1996). "Species resolution inTriceratops:cladistic and morphometric approaches ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.16(2): 259–270.Bibcode:1996JVPal..16..259F.doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011313.

- ^Lehman, T. M. (1998). "A gigantic skull and skeleton of the horned dinosaurPentaceratops sternbergifrom New Mexico ".Journal of Paleontology.72(5): 894–906.Bibcode:1998JPal...72..894L.doi:10.1017/S0022336000027220.JSTOR1306666.S2CID132807103.

- ^Scannella, J. B.; Fowler, D. W. (2009). "Anagenesis inTriceratops:evidence from a newly resolved stratigraphic framework for the Hell Creek Formation ".9th North American Paleontological Convention Abstracts.Cincinnati Museum Center Scientific Contributions 3. pp. 148–149.

- ^abPaul, G. S.(2010).The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs.Princeton University Press. pp.265–267.ISBN978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012).Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages(PDF).

Winter 2011 Appendix

- ^Stein, Walter W. (2019)."TAKING COUNT: A Census of Dinosaur Fossils Recovered From the Hell Creek and Lance Formations (Maastrichtian)"(PDF).The Journal of Paleontological Sciences.8:1–42.

- ^"ATriceratopsNamed 'Kelsey'".bhigr.Archivedfrom the original on December 23, 2017.RetrievedDecember 22,2017.

- ^"Kesley theTriceratops".bhigr.

- ^abcdScannella, J.; Horner, J.R. (2010). "TorosaurusMarsh, 1891, isTriceratopsMarsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): synonymy through ontogeny ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.30(4): 1157–1168.Bibcode:2010JVPal..30.1157S.doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483632.S2CID86767957.

- ^Lambert, D. (1993).The Ultimate Dinosaur Book.Dorling Kindersley, New York. pp.152–167.ISBN978-1-56458-304-8.

- ^abcdefghijklmnDodson, P.; Forster, C. A.; Sampson, S. D. (2004). "Ceratopsidae". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.).The Dinosauria(second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 494–513.ISBN978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^"Denver museum unveils 7-foot-long, 1,000-pound Triceratops skull".The Daily Courier. November 18, 2003.Archivedfrom the original on May 19, 2021.RetrievedDecember 26,2013.

- ^Scannella, John B.; Fowler, Denver W.; Goodwin, Mark B.; Horner, John R. (July 15, 2014)."Evolutionary trends in Triceratops from the Hell Creek Formation, Montana".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.111(28): 10245–10250.Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110245S.doi:10.1073/pnas.1313334111.ISSN0027-8424.PMC4104892.PMID24982159.

- ^"Making A Triceratops. Science Supplies Missing Part! Of Skeleton".Boston Evening Transcript. October 24, 1901.Archivedfrom the original on May 19, 2021.RetrievedDecember 26,2013.

- ^abcFujiwara, Shin-Ichi (December 12, 2009). "A reevaluation of the manus structure inTriceratops(Ceratopsia: Ceratopsidae) ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.29(4): 1136–1147.Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1136F.doi:10.1671/039.029.0406.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID86519018.

- ^Christiansen, P.; Paul, G.S. (2001)."Limb bone scaling, limb proportions, and bone strength in neoceratopsian dinosaurs"(PDF).Gaia.16:13–29.Archived(PDF)from the original on August 19, 2018.RetrievedOctober 29,2012.

- ^Thompson, S.; Holmes, R. (2007)."Forelimb stance and step cycle inChasmosaurus irvinensis(Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) ".Palaeontologia Electronica.10(1): 17 p.Archivedfrom the original on December 11, 2018.RetrievedNovember 20,2010.

- ^Rega, E.; Holmes, R.; Tirabasso, A. (2010). "Habitual locomotor behavior inferred from manual pathology in two Late Cretaceous chasmosaurine ceratopsid dinosaurs,Chasmosaurus irvinensis(CMN 41357) andChasmosaurus belli(ROM 843) ". In Ryan, Michael J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, Brenda J.; Eberth, David A. (eds.).New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium.Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 340–354.ISBN978-0-253-35358-0.

- ^Martin, Anthony J. (2006).Introduction to the study of dinosaurs(2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.ISBN978-1405134132.OCLC61130756.

- ^Bell, Phil R.; Hendrickx, Christophe; Pittman, Michael; Kaye, Thomas G.; Mayr, Gerald (August 12, 2022)."The exquisitely preserved integument of Psittacosaurus and the scaly skin of ceratopsian dinosaurs".Communications Biology.5(1): 809.doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03749-3.ISSN2399-3642.PMC9374759.PMID35962036.

- ^"What is special about the Triceratops?".Dinosaurios.org. July 24, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on May 31, 2020.RetrievedDecember 26,2013.

- ^Lambe, Lawrence M. (1915).On Eoceratops canadensis, gen. nov., with remarks on other genera of Cretaceous horned dinosaurs.Ottawa: Geological Survey of Canada, Government Printing Bureau.ISBN0-665-82611-7.OCLC920394016.

- ^abOstrom, J. H. (1966). "Functional morphology and evolution of the ceratopsian dinosaurs".Evolution.20(3): 290–308.doi:10.2307/2406631.JSTOR2406631.PMID28562975.

- ^Norman, David (1985).The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Dinosaurs.London: Salamander Books.ISBN978-0-517-46890-6.

- ^Dodson, P.;Currie, P. J. (1990). "Neoceratopsia". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.).The Dinosauria.Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 593–618.ISBN978-0-520-06727-1.

- ^Dodson, P. (1993)."Comparative craniology of the Ceratopsia"(PDF).American Journal of Science.293:200–234.Bibcode:1993AmJS..293..200D.doi:10.2475/ajs.293.A.200.Archived(PDF)from the original on August 19, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 21,2007.

- ^Longrich, N. R. (2014). "The horned dinosaurs Pentaceratops and Kosmoceratops from the upper Campanian of Alberta and implications for dinosaur biogeography".Cretaceous Research.51:292–308.Bibcode:2014CrRes..51..292L.doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.06.011.

- ^Gauthier, J. A. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight, K. Padian (ed.)".Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences.8:1–55.

- ^Sereno, P. C. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria".Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen.210(1): 41–83.doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41.

- ^abMathews, Joshua C.; Brusatte, Stephen L.; Williams, Scott A.; Henderson, Michael D. (2009). "The firstTriceratopsbonebed and its implications for gregarious behavior ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.29(1): 286–290.Bibcode:2009JVPal..29..286M.doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10010382.S2CID196608646.

- ^Smith, Matt (June 4, 2013)."Triceratops trio unearthed in Wyoming – CNN".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on August 1, 2017.RetrievedDecember 22,2017.

- ^Illies, M. M. Canoy; Fowler, D. W. (2020). "Triceratopswith a kink: Co-ossification of five distal caudal vertebrae from the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota ".Cretaceous Research.108:104355.Bibcode:2020CrRes.10804355C.doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104355.S2CID214215413.

- ^Barrera, Nathanial A. (January 9, 2020)."More than old bones: New study sheds light on Triceratops behavior and living habits".The Dickinson Press.Archivedfrom the original on May 27, 2020.RetrievedMarch 31,2020.

- ^Erickson, B. R. (1966). "Mounted skeleton ofTriceratops prorsusin the Science Museum ".Scientific Publications of the Science Museum.1:1–16.

- ^abBakker, R. T. (1986).The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking The Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction.New York: William Morrow. p.438.ISBN978-0-14-010055-6.

- ^Derstler, K. (1994). "Dinosaurs of the Lance Formation in eastern Wyoming". In Nelson, G. E. (ed.).The Dinosaurs of Wyoming.Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, 44th Annual Field Conference. Wyoming Geological Association. pp. 127–146.

- ^Sakagami, Rina; Kawabe, Soichiro (2020)."Endocranial anatomy of the ceratopsid dinosaur Triceratops and interpretations of sensory and motor function".PeerJ.8:e9888.doi:10.7717/peerj.9888.PMC7505063.PMID32999761.

- ^Wiemann, J.; Menéndez, I.; Crawford, J.M.; Fabbri, M.; Gauthier, J.A.; Hull, P.M.; Norell, M.A.; Briggs, D.E.G. (2022)."Fossil biomolecules reveal an avian metabolism in the ancestral dinosaur".Nature.606(7914): 522–526.Bibcode:2022Natur.606..522W.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04770-6.PMID35614213.S2CID249064466.

- ^Tait, J.; Brown, B. (1928). "How the Ceratopsia carried and used their head".Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada.22:13–23.

- ^Ostrom, J. H. (1964)."A functional analysis of jaw mechanics in the dinosaurTriceratops"(PDF).Postilla.88:1–35. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on June 26, 2010.RetrievedNovember 20,2010.

- ^Weishampel, D. B. (1984).Evolution of Jaw Mechanisms in Ornithopod Dinosaurs.Advances in Anatomy Embryology and Cell Biology. Vol. 87. pp. 1–110.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69533-9.ISBN978-3-540-13114-4.PMID6464809.S2CID12547312.

- ^Coe, M. J.; Dilcher, D. L.; Farlow, J. O.; Jarzen, D. M.; Russell, D. A. (1987). "Dinosaurs and land plants". In Friis, E. M.; Chaloner, W. G.; Crane, P. R. (eds.).The Origins of Angiosperms and their Biological Consequences.Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–258.ISBN978-0-521-32357-4.

- ^Lull, R. S. (1908)."The cranial musculature and the origin of the frill in the ceratopsian dinosaurs".American Journal of Science.4(25): 387–399.Bibcode:1908AmJS...25..387L.doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-25.149.387.Archivedfrom the original on November 15, 2019.RetrievedJune 12,2019.

- ^abForster, C. A. (1990).The cranial morphology and systematics ofTriceratops,with a preliminary analysis of ceratopsian phylogeny(Ph.D. Dissertation thesis). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. p. 227.

- ^Sternberg, C. H. (1917).Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada.San Diego, California. p. 261.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Happ, J. (2008). "An analysis of predator-prey behavior in a head-to-head encounter betweenTyrannosaurus rexandTriceratops".In Larson, P.; Carpenter, K. (eds.).Tyrannosaurus rex, the Tyrant King (Life of the Past).Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 355–368.ISBN978-0-253-35087-9.

- ^Erickson, Gregory M.; Olson, Kenneth H. (March 19, 1996)."Bite marks attributable to Tyrannosaurus rex: Preliminary description and implications".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.16(1): 175–178.Bibcode:1996JVPal..16..175E.doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011297.ISSN0272-4634.Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021.RetrievedJune 3,2020.

- ^Farke, A. A. (2004)."Horn Use inTriceratops(Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae): Testing Behavioral Hypotheses Using Scale Models "(PDF).Palaeo-electronica.7(1): 1–10.Archived(PDF)from the original on March 3, 2016.RetrievedNovember 20,2010.

- ^Tanke, D. H.; Farke, A. A. (2006). "Bone resorption, bone lesions, and extracranial fenestrae in ceratopsid dinosaurs: a preliminary assessment". In Carpenter, K. (ed.).Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs.Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 319–347.ISBN978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^Farke, A.A.; Wolff, E.D.S.; Tanke, D.H.; Sereno, Paul (2009). Sereno, Paul (ed.)."Evidence of Combat inTriceratops".PLOS ONE.4(1): e4252.Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4252F.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004252.PMC2617760.PMID19172995.

- ^Peterson, JE; Dischler, C; Longrich, NR (2013)."Distributions of Cranial Pathologies Provide Evidence for Head-Butting in Dome-Headed Dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae)".PLOS ONE.8(7): e68620.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868620P.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068620.PMC3712952.PMID23874691.

- ^Wall, Michael (January 27, 2009)."Scars Reveal How Triceratops Fought –".Wired.Archivedfrom the original on January 12, 2014.RetrievedAugust 3,2010.

- ^Reid, R.E.H. (1997). "Histology of bones and teeth". In Currie, P. J.; Padian, K. (eds.).Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs.San Diego, CA.: Academic Press. pp. 329–339.

- ^Horner, JR; Goodwin, MB (2009)."Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus".PLOS ONE.4(10): e7626.Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7626H.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626.PMC2762616.PMID19859556.

- ^Horner, JR; Lamm, E (2011). "Ontogeny of the parietal frill of Triceratops: a preliminary histological analysis".Comptes Rendus Palevol.10(5–6): 439–452.doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.04.006.

- ^abFarlow, J. O.; Dodson, P. (1975). "The behavioral significance of frill and horn morphology in ceratopsian dinosaurs".Evolution.29(2): 353–361.doi:10.2307/2407222.JSTOR2407222.PMID28555861.

- ^Martin, A. J. (2006).Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs(Second ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 299–300.ISBN978-1-4051-3413-2.

- ^D’Anastasio, Ruggero; Cilli, Jacopo; Bacchia, Flavio; Fanti, Federico; Gobbo, Giacomo; Capasso, Luigi (April 7, 2022)."Histological and chemical diagnosis of a combat lesion in Triceratops".Scientific Reports.12(1): 3941.Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.3941D.doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08033-2.ISSN2045-2322.PMC8990019.PMID35393445.

- ^Wheeler, P.E. (1978). "Elaborate CNS cooling structures in large dinosaurs".Nature.275(5679): 441–443.Bibcode:1978Natur.275..441W.doi:10.1038/275441a0.PMID692723.S2CID4160470.

- ^Farlow, J. O.; Thompson, C. V.; Rosner, D. E. (1976). "Plates of the dinosaurStegosaurus:Forced convection heat loss fins? ".Science.192(4244): 1123–5.Bibcode:1976Sci...192.1123F.doi:10.1126/science.192.4244.1123.PMID17748675.S2CID44506996.

- ^Davitashvili, L. Sh. (1961).Teoriya Polovogo Otbora (Theory of Sexual Selection).Izdatel'stvo Akademii nauk SSSR. p. 538.

- ^Goodwin, M.B.; Clemens, W.A.; Horner, J.R. & Padian, K. (2006)."The smallest knownTriceratopsskull: new observations on ceratopsid cranial anatomy and ontogeny "(PDF).Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.26(1): 103–112.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[103:TSKTSN]2.0.CO;2.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID31117040.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on November 5, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 21,2007.

- ^Hone, D. W. E.; Naish, D. (2013)."The 'species recognition hypothesis' does not explain the presence and evolution of exaggerated structures in non-avialan dinosaurs".Journal of Zoology.290(3): 172–180.doi:10.1111/jzo.12035.

- ^Horner, J.R.; Goodwin, M.B. (2006)."Major cranial changes duringTriceratopsontogeny ".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.273(1602): 2757–2761.doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3643.PMC1635501.PMID17015322.

- ^abFarke, A. A. (2006). "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsidTorosaurus latus".In Carpenter, K. (ed.).Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs.Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 235–257.ISBN978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^"New Analyses Of Dinosaur Growth May Wipe Out One-third Of Species".Science News.ScienceDaily. October 31, 2009.Archivedfrom the original on February 5, 2019.RetrievedNovember 3,2009.

- ^abcFarke, Andrew A. (2011). Claessens, Leon (ed.)."Anatomy and taxonomic status of the chasmosaurine ceratopsidNedoceratops hatcherifrom the Upper Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A ".PLOS ONE.6(1): e16196.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616196F.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016196.PMC3024410.PMID21283763.

- ^Longrich, Nicholas R.; Field, Daniel J. (February 29, 2012)."Torosaurus Is Not Triceratops: Ontogeny in Chasmosaurine Ceratopsids as a Case Study in Dinosaur Taxonomy".PLOS ONE.7(2): e32623.Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732623L.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032623.ISSN1932-6203.PMC3290593.PMID22393425.

- ^abBowdler, Neil (March 1, 2012)."Triceratops and Torosaurus dinosaurs 'two species, not one'".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on March 15, 2013.RetrievedJuly 29,2013.

- ^Scannella, J. B.; Horner, J. R. (2011). Claessens, Leon (ed.)."'Nedoceratops': An Example of a Transitional Morphology ".PLOS ONE.6(12): e28705.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628705S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028705.PMC3241274.PMID22194891.

- ^Longrich, Nicholas R. (2011). "Titanoceratops ouranous,a giant horned dinosaur from the Late Campanian of New Mexico ".Cretaceous Research.32(3): 264–276.Bibcode:2011CrRes..32..264L.doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.007.

- ^abcdefghiWeishampel, D.B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, H. (2004).The Dinosauria(Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 861.ISBN978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^Husson, D. E.; Galbrun, B.; Laskar, J.; Hinnov, L. A.; Thibault, N.; Gardin, S.; Locklair, R. E. (2011). "Astronomical calibration of the Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous)".Earth and Planetary Science Letters.305(3–4): 328–340.Bibcode:2011E&PSL.305..328H.doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.03.008.

- ^abLongrich, N. R.; Tokaryk, T.; Field, D. J. (2011)."Mass extinction of birds at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.108(37): 15253–15257.Bibcode:2011PNAS..10815253L.doi:10.1073/pnas.1110395108.PMC3174646.PMID21914849.

- ^abLamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014)."A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America".PLOS ONE.9(3): e92022.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992022L.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.PMC3960162.PMID24647078.

- ^Evans, D. C.; Larson, D. W.; Currie, P. J. (2013). "A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) with Asian affinities from the latest Cretaceous of North America".Naturwissenschaften.100(11): 1041–1049.Bibcode:2013NW....100.1041E.doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1107-5.PMID24248432.S2CID14978813.

- ^Triebold, M. (1997). Wolberg, D.; Stump, E.; Rosenberg, G. (eds.). "The Sandy site: Small dinosaurs from the Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota".Dinofest International: Proceedings of a Symposium:245–248.

- ^Maltese, Anthony (December 17, 2013)."Giant Oviraptor Tracks from the Hell Creek".RMDRC paleo lab.Archivedfrom the original on November 12, 2020.RetrievedDecember 17,2013.

- ^Martin, L. D.; Kurochkin, E. N.; Tokaryk, T. T. (2012). "A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia".Palaeoworld.21:59–63.doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2012.02.005.

- ^Ott, C.J.; Larson, P.L. (2010). "A New, Small Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, Northwest South Dakota, United States: A Preliminary Description". In Ryan, M.J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, B.J.; Eberth, D.A. (eds.).New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium.Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 656.

- ^Campione, N. S. E.; Evans, D. C. (2011)."Cranial Growth and Variation in Edmontosaurs (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae): Implications for Latest Cretaceous Megaherbivore Diversity in North America".PLOS ONE.6(9): e25186.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625186C.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025186.PMC3182183.PMID21969872.

- ^Bakker, R.T.; Sullivan, R.M.; Porter, V.; Larson, P.; Saulsbury, S.J. (2006). Lucas, S.G.; Sullivan, R.M. (eds.)."Dracorex hogwartsia,n. gen., n. sp., a spiked, flat-headed pachycephalosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota ".Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin.35:331–345.Archivedfrom the original on November 19, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 6,2015.

- ^abcdeKielan-Jaworowska, Zofia;Cifelli, Richard L.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (2004).Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs: Origins, Evolution, and Structure.New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 98–99.ISBN978-0-231-11918-4.

- ^abWilson, G. P. (2013)."Mammals across the K/Pg boundary in northeastern Montana, U.S.A.: Dental morphology and body-size patterns reveal extinction selectivity and immigrant-fueled ecospace filling".Paleobiology.39(3): 429–469.Bibcode:2013Pbio...39..429W.doi:10.1666/12041.S2CID36025237.

- ^abArchibald, J. D.; Zhang, Y.; Harper, T.; Cifelli, R. L. (2011). "Protungulatum, Confirmed Cretaceous Occurrence of an Otherwise Paleocene Eutherian (Placental?) Mammal".Journal of Mammalian Evolution.18(3): 153–161.doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9162-1.S2CID16724836.

- ^State of South Dakota."Signs and Symbols of South Dakota..."Archived fromthe originalon February 20, 2008.RetrievedJanuary 20,2007.

- ^State of Wyoming."State of Wyoming – General Information".Archived fromthe originalon February 10, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 20,2007.

- ^abBakker, R. T. (1986).The Dinosaur Heresies.New York: Kensington Publishing. p. 240.On that page, Bakker has his ownT. rex/Triceratopsfight.

External links[edit]

Media related toTriceratopsat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toTriceratopsat Wikimedia Commons Wikijunior Dinosaurs/Triceratopsat Wikibooks

Wikijunior Dinosaurs/Triceratopsat Wikibooks Works related toNotice of Gigantic Horned Dinosauria from the Cretaceousat Wikisource

Works related toNotice of Gigantic Horned Dinosauria from the Cretaceousat Wikisource Data related toTriceratopsat Wikispecies

Data related toTriceratopsat Wikispecies- Triceratopsat The Dinosaur Picture Database

- LiveScience: Facts aboutTriceratopsat LiveScience

- Clash of the Dinosaurs: The Defenders – The Triceratops ThreatonYouTube

- Dinosaur Mailing List post onTriceratopsstanceArchivedOctober 13, 2007, at theWayback Machine

- Smithsonian Exhibit

- Triceratopsin the Dino Directory

- Triceratops(short summary and good color illustration)

- TriceratopsFor Kids(a fact sheet about theTriceratopswith activities for kids)

- Triceratops,BBCDinosaurs

- (in French)TriceratopsArchivedOctober 17, 2016, at theWayback Machine–ListedeDinosauriaetExtinction

- Chasmosaurines

- Fossil taxa described in 1889

- Hell Creek fauna

- Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America

- Maastrichtian genera

- Symbols of South Dakota

- Symbols of Wyoming

- Taxa named by Othniel Charles Marsh

- Lance fauna

- Scollard fauna

- Paleontology in Colorado

- Paleontology in Wyoming

- Paleontology in South Dakota

- Paleontology in Alberta

- Paleontology in Saskatchewan

- Laramie Formation

- Ornithischian genera

- Multispecific non-avian dinosaur genera

- Late Cretaceous ceratopsians

- Ceratopsians of North America