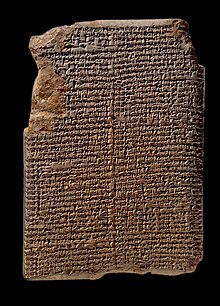

Babylonian calendar

TheBabylonian calendarwas alunisolar calendarused inMesopotamiafrom around thesecond millennium BCEuntil theSeleucid Era(294 BCE), and it was specifically used inBabylonfrom theOld Babylonian Period(1780 BCE) until the Seleucid Era. The civil lunisolar calendar was used contemporaneously with an administrative calendar of 360 days, with the latter used only in fiscal or astronomical contexts.[1]The lunisolar calendar descends from an older Sumerian calendar used in the4thand3rd millennia BCE.[2]

The civil lunisolar calendar had years consisting of 12lunar months,each beginning when a newcrescent moonwas first sighted low on the western horizon at sunset, plus anintercalary monthinserted as needed, at first by decree and then later systematically according to what is now known as theMetonic cycle.[3]

Month names from the Babylonian calendar appear in theHebrew calendar,Assyrian calendar,Syriac calendar,Old Persian calendar,andTurkish calendar.

Civil calendar

[edit]The Babylonian civil calendar, also called the cultic calendar, was a lunisolar calendar descended from the Nippur calendar, which has evidence of use as early as 2600 BCE and descended from the even olderThird Dynasty of Ur(Ur III) calendar. The original Sumerian names of the months are seen in the orthography for the next couple millennia, albeit in more and more shortened forms. When the calendar came into use in Babylon circa 1780 BCE, the spoken month names became a mix from the calendars of the local subjugated cities, which were Akkadian. Historians agree that it was probablySamsu-ilunawho effected this change.[3]During the sixth century BCEBabylonian captivity of the Jews,these month names were adopted into theHebrew calendar.

The first month of the civil calendar during the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods wasŠekinku(Akk.Addaru), or the month of barley harvesting, and it aligned with thevernal equinox.However, during the intervening Nippur period, it was the twelfth month instead.[3]

Until the5th century BCE,the calendar was fully observational, and the intercalary month was inserted approximately every two to three years, at first by guidelines which survive in theMUL.APINtablet. Beginning in around499 BCE,the intercalation began to be regulated by a predictablelunisolarcycle, so that 19 years comprised 235 months.[3]Although this 19-year cycle is usually called theMetonic cycleafterMeton of Athens(432 BCE), the Babylonians used this cycle before Meton, and it may be that Meton learned of the cycle from the Babylonians.[4]After no more than three isolated exceptions, by380 BCEthe months of the calendar were regulated by the cycle without exception. In the cycle of 19 years, the monthAddaru2was intercalated, except in the year that was number 17 in the cycle, when the monthUlūlu 2was inserted instead.[3]

During this period, the first day of each month (beginning at sunset) continued to be the day when a new crescent moon was first sighted—the calendar never used a specified number of days in any month. However, as astronomical science grew in Babylon, the appearance of the new moon was predictable with some accuracy into the short-term future. Still, during theNeo-Assyrian period(c. 700 BCE) the calendar was sometimes retroactively "shifted back" a day to account for the fact that the king should have declared a new month, but only did so the following day because ofobstructive weather.[5]

| Sumerian month names[3] | Akkadian month names[3] | Equivalents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | Mandaean[6] | Levantine and Iraqi | Gregorian | |||

| 1 | 𒌚𒁈𒍠(𒃻)ITIBARA2.ZAG(.GAR) – 'Month [the proxies of the gods are] placed besides the throne' | Araḫ Nisānu–𒌚𒁈[7][8] | Nisan

נִיסָן |

Nisan

ࡍࡉࡎࡀࡍ |

Naysān نَيْسَان | Mar/April |

| 2 | 𒌚[𒂡]𒄞𒋛𒋢ITI[EZEM.]GU4.SI.SU – 'Month the horned oxen marched forth' | Araḫ Āru-𒌚𒄞– 'Month of the Blossoming'[7] | Iyar

אִיָּיר |

Ayar

ࡀࡉࡀࡓ |

Ayyār أَيَّار | Apr/May |

| 3 | 𒌚𒋞𒄷𒋛𒊒𒁀𒂷𒃻ITISIG4.U5.ŠUB.BA.GÁ.GAR – 'Month the brick is placed in the mold' | Araḫ Simanu– 𒌚𒋞 | Sivan

סִיוָן |

Siwan

ࡎࡉࡅࡀࡍ |

Ḥazīrān حَزِيرَان | May/Jun |

| 4 | 𒌚𒋗𒆰ITIŠU.NUMUN – 'Month of preparing for seed, festival' | Araḫ Dumuzu– 𒌚𒋗 | Tammuz

תַּמּוּז |

Tamuz/Tammuz

ࡕࡀࡌࡅࡆ |

Tammūz تَمُّوز | Jun/Jul |

| 5 | 𒌚𒉈𒉈𒃻ITINE.IZI.GAR – 'Month when the braziers are lit' | Araḫ Abu– 𒌚𒉈 | Av (month)

אָב |

Ab

ࡀࡁ |

Āb آب | Jul/Aug |

| 6 | 𒌚𒆥𒀭𒈹ITIKIN.dINANNA – 'Month of the rectification of Inanna' | Araḫ Ulūlu– 𒌚𒆥 | Elul

אֱלוּל |

Aylul

ࡀࡉࡋࡅࡋ |

Aylūl أَيْلُول | Aug/Sep |

| 7 | 𒌚𒇯𒆬ITIDU6.KÙ – 'Month of the Sacred Mound' | Araḫ Tišritum– 𒌚𒇯

'Month of Beginning'[9] |

Tishrei

תִּשְׁרֵי |

Tišrin

ࡕࡉࡔࡓࡉࡍ |

Tishrīn al-Awwal تِشْرِين الْأَوَّل | Sep/Oct |

| 8 | 𒌚(𒄑)𒀳𒂃𒀀ITI(GIŠ)APIN.DU8.A – 'Month the plow is let go' | Araḫ Samnu– 𒌚𒀳

'Month the Eighth'[9] |

Cheshvan

מַרְחֶשְׁוָן/חֶשְׁוָן |

Mašrwan

ࡌࡀࡔࡓࡅࡀࡍ |

Tishrīn ath-Thānī تِشْرِين الثَّانِي | Oct/Nov |

| 9 | 𒌚𒃶𒃶(𒈬)𒌓𒁺ITIGAN.GAN.(MU.)E3– 'Month when the clouds(?) come out' | Araḫ Kislimu– 𒌚𒃶 | Kislev

כִּסְלֵו |

Kanun

ࡊࡀࡍࡅࡍ |

Kānūn al-Awwal كَانُون الْأَوَّل | Nov/Dec |

| 10 | 𒌚𒀊𒌓𒁺ITIAB.E3– 'Month of the father' | Araḫ Ṭebētum– 𒌚𒀊

'Muddy Month'[9] |

Tebeth

טֵבֵת |

Ṭabit

ࡈࡀࡁࡉࡕ |

Kānūn ath-Thānī كَانُون الثَّانِي | Dec/Jan |

| 11 | 𒌚𒍩𒀀ITIZIZ2.A – 'Month foremmer' | Araḫ Šabaṭu–𒌚𒍩 | Shebat

שְׁבָט |

Šabaṭ

ࡔࡀࡁࡀࡈ |

Shubāṭ شُبَاط | Jan/Feb |

| 12 | 𒌚𒊺𒆥𒋻ITIŠE.KIN.KU5– 'Month of the cutting of corn, harvest month'[9][10][11] | Araḫ Addaru /Adār–𒌚𒊺 | Adar

אֲדָר (אֲדָר א׳/אֲדָר רִאשׁון if there is an intercalary month that year) |

Adar

ࡀࡃࡀࡓ |

Ādhār آذَار | Feb/Mar |

| 13 | 𒌚𒋛𒀀𒊺𒆥𒋻ITIDIRI.ŠE.KIN.KU5– 'Additional harvest month' | Araḫ Makaruša Addari[citation needed]

Araḫ Addaru Arku–𒌚𒋛𒀀𒊺 |

Adar II

אֲדָר ב׳/אֲדָר שֵׁנִי |

Mart (Âzâr) | ||

Accuracy

[edit]As a lunisolar calendar, the civil calendar aimed to keep calendar months in sync with thesynodic monthand calendar years in sync with thetropical year.Since new months of the civil calendar were declared by observing the crescent moon, the calendar months could not drift from the synodic month. On the other hand, since the length of a calendar year was handled by the Metonic cycle starting after 499 BCE, there is some inherent drift present in the formulaic computation of the new year when compared to the true new year. While on any given year the first day of the first month could be up to 20 days off from thevernal equinox,on average the length of a year was very well approximated by the Metonic cycle; the computed average length is within 30 minutes of the true solar year length.[12]

Administrative calendar

[edit]

Since the civil calendar was not standardized and predictable for at least the first millennium of its use, a second calendar system thrived in Babylon during the same time spans, known today as the administrative or schematic calendar. The administrative year consisted of 12 months of exactly 30 days each. In the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, extra months were occasionally intercalated (in which case the year is 390 days), but by the beginning of the 2nd millenium BCE it did not make any intercalations or modifications to the 360-day year.[3]This calendar saw use in areas requiring precision in dates or long-term planning; there is tablet evidence demonstrating it was used to date business transactions andastronomical observations,and thatmathematics problems,wage calculations, and tax calculations all assumed the administrative calendar instead of the civil calendar.[1]

Babylonian astronomers in particular made all astral calculations and predictions in terms of the administrative calendar. Discrepancies were accounted for in different ways according to the heavenly measurements being taken. When predicting thephase of the moon,it was treated as if each ideal month began with anew moon,even though this could not be true. In fact, this guideline appears in the MUL.APIN, which goes on further to specify that months that began "too early" (on the 30th of the previous month) were considered unlucky, and months that began "on time" (the day after the 30th of the previous month) were considered auspicious. When discussing the dates ofequinoxesandsolstices,the events were assigned fixed days of the administrative calendar, withshortening or lengtheningof intervening days taking place to ensure that the celestial phenomena would fall on the "correct" day. Which fixed day each phenomenon was assigned varied throughout time, for one because which month was designated first varied throughout history. In general, they were assigned to the 15th day of four equally spaced months.[3]

Seven-day week and Sabbath

[edit]Counting from thenew moon,the Babylonians celebrated every seventh day as a "holy-day", also called an "evil-day" (meaning "unsuitable" for prohibited activities). On these days officials were prohibited from various activities and common men were forbidden to "make a wish", and at least the 28th was known as a "rest-day". On each of them, offerings were made to a different god and goddess, apparently at nightfall to avoid the prohibitions:MardukandIshtaron the 7th,NinlilandNergalon the 14th,SinandShamashon the 21st, andEnkiandMahon the 28th. Tablets from the sixth-century BC reigns ofCyrus the GreatandCambyses IIindicate these dates were sometimes approximate. Thelunationof 29 or 30 days basically contained threeseven-day weeks,and a final week of eight or nine days inclusive, breaking the continuous seven-day cycle.[13]

Among other theories ofShabbatorigin, theUniversal Jewish EncyclopediaofIsaac Landmanadvanced a theory ofAssyriologistslikeFriedrich Delitzsch[14]thatShabbatoriginally arose from thelunar cycle,[15][16]containing four weeks ending in Sabbath, plus one or two additional unreckoned days per month.[17]The difficulties of this theory include reconciling the differences between an unbroken week and a lunar week, and explaining the absence of texts naming the lunar week asShabbatin any language.[18]

The rarely attestedSapattumorSabattumas thefull moonis cognate or merged with HebrewShabbat,but is monthly rather than weekly; it is regarded as a form of Sumeriansa-bat( "mid-rest" ), attested in Akkadian asum nuh libbi( "day of mid-repose" ). According toMarcello Craveri,Sabbath "was almost certainly derived from the BabylonianShabattu,the festival of the full moon, but, all trace of any such origin having been lost, the Hebrews ascribed it to Biblical legend. "[19]This conclusion is a contextual restoration of the damagedEnûma Elišcreation account, which is read as: "[Sa]bbath shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly."[13]

Impact

[edit]The Akkadian names for months surface in a number of calendars still used today. InIraqand theLevant,the solarGregorian calendarsystem is used, withClassical Arabic names replacing the Roman ones,[20]and the month names in theAssyrian calendardescend directly from Aramaic, which descended from Akkadian.[21]Similarly, while Turkey uses the Gregorian calendar in the present day, the names ofTurkish monthswere inspired by the 1839Rumi calendarof theOttoman Empire,itself derived from the Ottoman fiscal calendar of 1677 based on theJulian calendar.This last calendar month names of both Syriac and Islamic origin, and in the modern calendar four of these names descend from the original Akkadian names.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abBrack-Bernsen, Lis (2007). "The 360-Day Year in Mesopotamia". In Steele, John M. (ed.).Calendars and Years: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient Near East.Oxbow Books. pp. 83–100.ISBN978-1-84217-302-2.

- ^Sharlach, Tonia (2013-08-29)."Calendars and Counting".In Crawford, Harriet (ed.).The Sumerian World.Routledge. pp. 311–318.ISBN978-1-136-21912-2.

- ^abcdefghiBritton, John P. (2007). "Calendars, Intercalations and Year-Lengths in Mesopotamian Astronomy". In Steele, John M. (ed.).Calendars and Years: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient Near East.Oxbow Books. pp. 115–132.ISBN978-1-84217-302-2.

- ^Hannah, Robert (2005).Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World.London: Duckworth. p. 56.ISBN0-7156-3301-5.

- ^Steele, John M. (2007). "The Length of the Month in Mesopotamian Calendars of the First Millenium BC". In Steele, John M. (ed.).Calendars and Years: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient Near East.Oxbow Books. pp. 133–148.ISBN978-1-84217-302-2.

- ^Häberl, Charles (2022).The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World: A Universal History from the Late Sasanian Empire.Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.ISBN978-1-80085-627-1.

- ^abcW. Muss-Arnolt (1892). "The Names of the Assyro-Babylonian Months and Their Regents".Journal of Biblical Literature.11(1): 72–94.doi:10.2307/3259081.hdl:2027/mdp.39015030576584.JSTOR3259081.S2CID165247741.

- ^Tinney, Steve (2017)."barag [SANCTUM] N".Oracc: The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus.RetrievedJune 5,2023.

- ^abcdMuss-Arnolt, W.,The Names of the Assyro-Babylonian Months and Their Regents,Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 11, No. 2 (1892), pp. 160-176 [163], accessed 9-8-2020

- ^Finkelstein, J. J. (1969). "THE EDICT OF AMMIṢADUQA: A NEW TEXT".Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie Orientale.63(1): 45–64.JSTOR23283452.

- ^Tinney, Steve (2017)."ŠE.KIN kud [REAP]".Oracc: The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus.RetrievedJune 5,2023.

- ^Richards, E. G. (1998-10-01).Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History.Oxford University Press. p. 95.doi:10.1093/oso/9780198504139.001.0001.ISBN978-1-383-02079-3.

- ^abPinches, T.G. (1919)."Sabbath (Babylonian)".In Hastings, James (ed.).Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics.Selbie, John A., contrib. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 889–891.

- ^Landau, Judah Leo.The Sabbath.Johannesburg:Ivri Publishing Society, Ltd. pp. 2, 12.Retrieved2009-03-26.

- ^Joseph, Max (1943). "Holidays". InLandman, Isaac(ed.).The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times.Vol. 5. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 410.

- ^Joseph, Max (1943). "Sabbath". InLandman, Isaac(ed.).The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times.Vol. 9. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 295.

- ^Cohen, Simon (1943). "Week". InLandman, Isaac(ed.).The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times.Vol. 10. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 482.

- ^Sampey, John Richard (1915)."Sabbath: Critical Theories".InOrr, James(ed.).The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia.Howard-Severance Company. p. 2630.

- ^Craveri, Marcello (1967).The Life of Jesus.Grove Press.p.134.

- ^Fröhlich, Werner."The months of the Gregorian (Christian) calendar in various languages".GEONAMES.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-17.Retrieved2011-07-17.

- ^Coakley, J.F. (2013-11-15).Robinson's Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar(6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 148.ISBN978-0-19-968717-6.

- ^Sener, Ömer; Sener, Mehmet."Turkish Months of the Year".ielanguages.Archived fromthe originalon 2023-09-30.Retrieved2024-01-25.

Bibliography

[edit]- Parker, Richard Anthony and Waldo H. Dubberstein.Babylonian Chronology 626 BC.–AD. 75.Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1956.

- W. Muss-Arnolt,The Names of the Assyro-Babylonian Months and Their Regents,Journal of Biblical Literature (1892).

- Sacha Stern, "The Babylonian Calendar at Elephantine" inZeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik130 (2000) 159–171 (PDF document,94 KB)

- Fales, Frederick Mario, “A List of Umma Month Names”, Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale, 76 (1982), 70–71.

- Gomi, Tohru, “On the Position of the Month iti-ezem-dAmar-dSin in the Neo-Sumerian Umma Calendar”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, 75 (1985), 4–6.

- Pomponio, Francesco, “The Reichskalender of Ur III in the Umma Texts”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiastische Archäologie, 79 (1989), 10–13.

- Verderame, Lorenzo, “Le calendrier et le compte du temps dans la pensée mythique suméro-akkadienne”, De Kêmi à Birit Nâri, Revue Internationale de l'Orient Ancien, 3 (2008), 121–134.

- Steele, John M., ed., "Calendars and Years: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient Near East", Oxford: Oxbow, 2007.