Vaishnavism

|

| Part ofa serieson |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

| Part ofa serieson |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Vaishnavism(Sanskrit:वैष्णवसम्प्रदायः,romanized:Vaiṣṇavasampradāyaḥ) is one of the majorHindu denominationsalong withShaivism,Shaktism,andSmartism.[1]It is also calledVishnuismsince it considersVishnuas the solesupreme beingleading all otherHindu deities,that is,Mahavishnu.[2][3]Its followers are called Vaishnavites orVaishnavas (IAST:Vaiṣṇava), and it includes sub-sects likeKrishnaismandRamaism,which considerKrishnaandRamaas the supreme beings respectively.[4][5] According to a 2010 estimate by Johnson and Grim, Vaishnavism is the largest Hindu sect, constituting about 641 million or 67.6% of Hindus.[6][7]

The ancient emergence of Vaishnavism is unclear, and broadly hypothesized as afusionof various regional non-Vedic religions with worship ofVishnu.It is considered a merger of several popular non-Vedic theistic traditions, particularly theBhagavatacults ofVāsudeva-Krishna[8][9]andGopala-Krishna,[8][10]as well asNarayana,[11]developed in the 7th to 4th century BCE.[8][12]It was integrated with the Vedic GodVishnuin the early centuries CE, andfinalizedas Vaishnavism,[8][13][14]when it developed theavatardoctrine, wherein the various non-Vedic deities are revered as distinct incarnations of the supreme GodVishnu.Rama,Krishna,Narayana,Kalki,Hari,Vithoba,Venkateshvara,Shrinathji,RanganathaandJagannathare among the names of popular avatars all seen as different aspects of the same supreme being.[15][16][17]

The Vaishnavite tradition is known for the loving devotion to an avatar of Vishnu (often Krishna), and as such was key to the spread of theBhakti movementinIndian subcontinentin the 2nd millennium CE.[18][19]It has fourVedanta-schools of numerous denominations (sampradaya): the medieval-eraVishishtadvaitaschool ofRamanuja,theDvaitaschool ofMadhvacharya,theDvaitadvaitaschool ofNimbarkacharya,and theShuddhadvaitaofVallabhacharya.[20][21]There are also several other Vishnu-traditions.Ramananda(14th century) created a Rama-oriented movement, now the largest monastic group in Asia.[22][23]

Key texts in Vaishnavism include theVedas,theUpanishads,theBhagavad Gita,thePancharatra(Agama) texts,Naalayira Divya Prabhandham,and theBhagavata Purana.[6][24][25][26]

History

Origins

Northern India

The ancient emergence of Vaishnavism is unclear, the evidence inconsistent and scanty.[32]Syncretism of various traditions resulted in Vaishnavism.[13][14]AlthoughVishnuwas a Vedic solar deity,[9]he is mentioned less often compared to Agni, Indra, and other Vedic deities, thereby suggesting that he had a minor position in the Vedic religion.[33]

According toDandekar,what is understood today as Vaishnavism did not originate in Vedism at all, but emerged from the merger of several popular theistic traditions which developed after the decline of Brahmanism at the end of the Vedic period, closely before thesecond urbanisationof northern India, in the 7th to 4th century BCE.[note 1]It initially formed as Vasudevism aroundVāsudeva,a deified leader of theVrishnis,and one of theVrishni heroes.[8]Later, Vāsudeva was amalgamated withKrishna"the deified tribal hero and religious leader of the Yadavas",[8][9]to form the merged deityBhagavan Vāsudeva-Krishna,[8]due to the close relation between the tribes of theVrishnisand the Yadavas.[8]This was followed by a merger with the cult ofGopala-Krishnaof the cowherd community of the Abhıras[8]in the 4th century CE.[10]The character of Gopala Krishna is often considered to be non-Vedic.[34]According to Dandekar, such mergers consolidated the position ofKrishnaismbetween the heterodox sramana movement and the orthodox Vedic religion.[8]The "Greater Krsnaism", states Dandekar, then adopted theRigvedic Vishnuas Supreme deity to increase its appeal towards orthodox elements.[8]

According toKlostermaier,Vaishnavism originates in the latest centuries BCE and the early centuries CE, with the cult of the heroic Vāsudeva, a leading member of theVrishni heroes,which was then amalgamated withKrishna,hero of theYadavas,and still several centuries later with the "divine child"Bala Krishnaof theGopalatraditions.[note 2]According to Klostermaier, "In some books Krishna is presented as the founder and first teacher of theBhagavatareligion. "[35]According to Dalal, "The term Bhagavata seems to have developed from the concept of the Vedic deityBhaga,and initially it seems to have been a monotheistic sect, independent of the Brahmanical pantheon. "[36]

The development of the Krishna-traditions was followed by a syncretism of these non-Vedic traditions with theMahabharatacanon, thus affiliating itself withVedismin order to become acceptable to theorthodoxestablishment. The Vishnu of theRig Vedawas assimilated into non-Vedic Krishnaism and became the equivalent of the Supreme God.[9]The appearance of Krishna as one of theAvatarsof Vishnu dates to the period of theSanskrit epicsin the early centuries CE. TheBhagavad Gita—initially, a Krishnaite scripture, according toFriedhelm Hardy—was incorporated into the Mahabharata as a key text for Krishnaism.[4][37]

Finally, the Narayana worshippers were also included, which further brahmanized Vaishnavism.[38]The Nara-Narayana worshippers may have originated in Badari, a northern ridge of the Hindu Kush, and absorbed into the Vedic orthodoxy as Purusa Narayana.[38]Purusa Narayana may have later been turned into Arjuna and Krsna.[38]

In the late-Vedic texts (~1000 to 500 BCE), the concept of a metaphysicalBrahmangrows in prominence, and the Vaishnavism tradition considered Vishnu to be identical to Brahman, just like Shaivism and Shaktism consider Shiva and Devi to be Brahman respectively.[39]

This complex history is reflected in the two main historical denominations of Vishnavism. TheBhagavats,worship Vāsudeva-Krishna,[40]and are followers of Brahmanic Vaishnavism, while the Pacaratrins regard Narayana as their founder, and are followers of Tantric Vaishnavism.[38][41]

Southern India

S. Krishnaswami Aiyangarstates that the lifetime of the VaishnavaAlvarswas during the first half of the 12th century, their works flourishing about the time of the revival of Brahminism and Hinduism in the north, speculating that Vaishnavism might have penetrated to the south as early as about the first century CE.[42]There also exists secular literature that ascribes the commencement of the tradition in the south to the 3rd century CE. U. V. Swaminathan Aiyar,a scholar of Tamil literature, published the ancient work of theSangamperiod known as theParipatal,which contains seven poems in praise of Vishnu, including references to Krishna and Balarama. Aiyangar references an invasion of the south by theMauryasin some of the older poems of the Sangam, and indicated that the opposition that was set up and maintained persistently against northern conquest had possibly in it an element of religion, the south standing up for orthodox Brahmanism against the encroachment of Buddhism by the persuasive eloquence and persistent effort of the Buddhist emperorAshoka.The Tamil literature of this period has references scattered all over to the colonies of Brahmans brought and settled down in the south, and the whole output of this archaic literature exhibits unmistakably considerable Brahman influence in the making up of that literature.[43]

The Vaishnava school of the south based its teachings on the NaradiyaPancharatraand theBhagavatafrom the north and laid stress on a life of purity, high morality, worship and devotion to only one God. Although the monism ofShankarawas greatly appreciated by the intellectual class, the masses came increasingly within the fold of Vishnu. Vaishnavism checked the elaborate rituals, ceremonials, vratas, fasts, and feasts prescribed by theSmritisandPuranasfor the daily life of a Hindu, and also the worship of various deities like the sun, the moon, the grahas or planets, enjoined by the priestly Brahmin class for the sake of emoluments and gain. It enjoined the worship of no other deities exceptNarayanaof theUpanishads,who was deemed the primal cause ofsrsti(creation),sthiti(existence) andpralaya(destruction). The accompanying philosophies ofAdvaitaandVishishtadvaitabrought the lower classes into the fold of practical Hinduism, and extended to them the right and privilege of knowing God and attainingmukti(salvation).[citation needed]

ThePallavadynasty of Tamilakam patronised Vaishnavism.Mahendra Varmanbuilt shrines both of Vishnu and Shiva, several of his cave-temples exhibiting shrines to Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. In the age of the Pallava domination, which followed immediately, both Vaishnavism and Shaivism flourished, fighting the insurgent Buddhists and Jains.[44]The Pallavas were also the first of various dynasties that offered land and wealth to theVenkatesvara templeat Tirumala, which would soon become the most revered religious site of South India.[citation needed]TheSri VaishnavaacharyaRamanujais credited with the conversion of theHoysalakingVishnuvardhana(originally called Bittideva) from Jainism to Vaishnavism, consolidating the faith in Karnataka.[45]TheChalukyasand their rivals of the Pallavas appear to have employed Vaishnavism as an assertion of divine kingship, one of them proclaiming themselves as terrestrial emanations of Vishnu while the other promptly adopted Shaivism as their favoured tradition, neither of them offering much importance to the other's deity.[46]TheSri Vaishnavasampradayaof Ramanuja would hold sway in the south, the Vadakalai denomination subscribing to Vedanta philosophy and the Tenkalai adhering to regional liturgies known as Prabandham.[47]

According toHardy,[note 3]there is evidence of early "southern Krishnaism", despite the tendency to allocate the Krishna-traditions to the Northern traditions.[48]South Indian texts show close parallel with the Sanskrit traditions of Krishna and his gopi companions, so ubiquitous in later North Indian text and imagery.[50]Early writings inTamils' culture such asManimekalaiand theCilappatikarampresent Krishna,his brother,and favourite female companions in the similar terms.[50]Hardy argues that the Sanskrit Bhagavata Purana is essentially a Sanskrit "translation" of the bhakti of the Tamilalvars.[51]

Devotion to the southern Indian Mal (Perumal) may be an early form of Krishnaism, since Mal appears as a divine figure, largely like Krishna with some elements of Vishnu.[52]TheAlvars,whose name can be translated "immersed", were devotees of Perumal. They codified the Vaishnava canon of the south with their most significant liturgy, theNaalayira Divya Prabandham,traced to the 10th century as a compilation by Nathamuni.[53]Their poems show a pronounced orientation to the Vaishnava, and often Krishna, side of Mal. But they do not make the distinction betweenKrishnaandVishnuon the basis of the concept of theavatars.[52]Yet, according to Hardy, the term "Mayonism" should be used instead of "Krishnaism" when referring to Mal or Mayon.[48]The early Alvars speak of glorifyingVishnu bhakti(devotion to Vishnu), but at the same time, they do regardShiva bhakti(devotion to Shiva) with considerable sympathy, and make a visible effort to keep the Shaivas in countenance. The earliest Alvars go the length of describing Shiva and Vishnu as one, although they do recognise their united form as Vishnu.[54]

Srirangam,the site of the largest functioning temple in the world of 600 acres,[55]is devoted toRanganathaswamy,a form of Vishnu. The legend goes that KingVibhishana,who was carrying the idol of Ranganatha on his way toLanka,took rest for a while by placing the statue on the ground. When he prepared to depart, he realised that the idol was stuck to the ground. So, he built a small shrine, which became a popular abode for the deity Ranganatha on the banks of the river Kaveri. The entire temple campus with great walls, towards, mandapas, halls with 1000 pillars were constructed over a period of 300 years from the 14th to 17th century CE.[citation needed]

Gupta era

Most of the Gupta kings, beginning withChandragupta II(Vikramaditya) (375–413 CE) were known as Parama Bhagavatas orBhagavataVaishnavas.[57][38]But following theHunainvasions, especially those of theAlchon Hunscirca 500 CE, theGupta Empiredeclined and fragmented, ultimately collapsing completely, with the effect of discrediting Vaishnavism, the religion it had been so ardently promoting.[58]The newly arising regional powers in central and northern India, such as theAulikaras,theMaukharis,theMaitrakas,theKalacurisor theVardhanaspreferred adoptingSaivisminstead, giving a strong impetus to the development of the worship ofShiva,and its ideology of power.[58]Vaisnavism remained strong mainly in the territories which had not been affected by these events:South IndiaandKashmir.[58]

Early medieval period

After the Gupta age, Krishnaism rose to a major current of Vaishnavism,[35]and Vaishnavism developed into various sects and subsects, most of them emphasizingbhakti,which was strongly influenced by south Indian religiosity.[38]Modern scholarship positNimbarkacharya(c.7th century CE) to this period who propounded Radha Krishna worship and his doctrine came to be known as (dvaita-advaita).[59]

Vaishnavism in the 10th century started to employ Vedanta-arguments, possibly continuing an older tradition of Vishnu-oriented Vedanta predatingAdvaita Vedanta.Many of the early Vaishnava scholars such as Nathamuni, Yamunacharya and Ramanuja, contestedAdi ShankarasAdvaita interpretations and proposed Vishnu bhakti ideas instead.[60][61]Vaishnavism flourished in predominantlyShaiviteTamil Naduduring the seventh to tenth centuries CE with the twelveAlvars,saints who spread the sect to the common people with their devotionalhymns.The temples that the Alvars visited or founded are now known asDivya Desams.Their poems in praise ofVishnuand Krishna inTamil languageare collectively known asNaalayiraDivya Prabandha(4000 divine verses).[62][63]

Later medieval period

TheBhakti movementof late medieval Hinduism started in the 7th century, but rapidly expanded after the 12th century.[64]It was supported by the Puranic literature such as theBhagavata Purana,poetic works, as well as many scholarlybhasyasandsamhitas.[65][66][67]

This period saw the growth of Vashnavism Sampradayas (denominations or communities) under the influence of scholars such asRamanujacharya,Vedanta Desika,MadhvacharyaandVallabhacharya.[68]Bhakti poets or teachers such asManavala Mamunigal,Namdev,Ramananda,Sankardev,Surdas,Tulsidas,Eknath,Tyagaraja,Chaitanya Mahaprabhuand many others influenced the expansion of Vaishnavism. EvenMirabaitook part in this specific movement.[69][70][71]These scholars rejectedShankara's doctrines of Advaita Vedanta, particularlyRamanujain the 12th century, andVedanta DesikaandMadhvain the 13th century, building their theology on the devotional tradition of theAlvars(Sri Vaishnavas).[72]

In North and Eastern India, Vaishnavism gave rise to various late Medieval movementsRamanandain the 14th century,Sankaradevain the 15th andVallabhaandChaitanyain the 16th century. Historically, it wasChaitanya Mahaprabhuwho founded congregational chanting of holy names of Krishna in the early 16th century after becoming asannyasi.[73]

Modern times

During the 20th century, Vaishnavism spread from India and is now practised in many places around the globe, including North America, Europe, Africa, Russia and South America. A pioneer of Vaishnavite mission to the West was sannyasiBaba Premananda Bharati(1858–1914), the author of the first full-length treatment of Bengali Vaishnavism in English,Sree Krishna—the Lord of Love.He founded the "Krishna Samaj" society inNew York Cityin 1902 and a temple inLos Angeles.[74]The global status of Vaishnavism is largely due to the growth of theISKCONmovement, founded byA. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupadain 1966.[75][76][77]

Beliefs

Theism with many varieties

Vaishnavism is centred on the devotion of Vishnu and his avatars. According to Schweig, it is a "polymorphic monotheism, i.e. a theology that recognises many forms (ananta rupa) of the one, single unitary divinity, "since there are many forms of one original deity, with Vishnu taking many forms.[78]Okita, in contrast, states that the different denominations within Vaishnavism are best described as theism,pantheismandpanentheism.[79]

The Vaishnava sampradaya started by Madhvacharya is a monotheistic tradition wherein Vishnu (Krishna) is omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent.[80]In contrast, Sri Vaishnavism sampradaya associated with Ramanuja has monotheistic elements, but differs in several ways, such as goddess Lakshmi and god Vishnu are considered as inseparable equal divinities.[81]According to some scholars, Sri Vaishnavism emphasizes panentheism, and not monotheism, with its theology of "transcendence and immanence",[82][83]where God interpenetrates everything in the universe, and all of empirical reality is God's body.[84][85]The Vaishnava sampradaya associated with Vallabhacharya is a form of pantheism, in contrast to the other Vaishnavism traditions.[86]The Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition of Chaitanya, states Schweig, is closer to a polymorphic bi-monotheism because both goddess Radha and god Krishna are simultaneously supreme.[87]

Vaishnavism precepts include theavatar(incarnation) doctrine, wherein Vishnu incarnates numerous times, in different forms, to set things right and bring back the balance in the universe.[88][89][90]These avatars include Narayana, Vasudeva, Rama and Krishna; each the name of a divine figure with attributed supremacy, which each associated tradition of Vaishnavism believes to be distinct.[91]

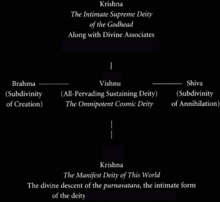

Vishnuism and Krishnaism

The term "Krishnaism" (Kṛṣṇaism) has been used to describe a large group of independent traditions-sampradayaswithin Vaishnavism regardedKrishnaas the Supreme God, while "Vishnuism" may be used for sects focusing on Vishnu in which Krishna is anAvatar,rather than a transcended Supreme Being.[4][5]Vishnuism believes in Vishnu as the supreme being. When all other Vaishnavas recognise Krishna as one of Vishnu'savatars,though only the Krishnites identify the Supreme Being (Svayam Bhagavan,Brahman,a source of the Trimurti) with Krishna and his forms (Radha Krishna,Vithobaand others), those manifested themselves as Vishnu. This is its difference from such groups asRamaism,Radhaism,Sitaism, etc.[4][92]As such Krishnaism is believed to be one of the early attempts to make philosophical Hinduism appealing to the masses.[93]In common language the term Krishnaism is not often used, as many prefer a wider term "Vaishnavism", which appeared to relate to Vishnu, more specifically as Vishnu-ism.

Vishnu

InVishnu-centeredsects, Vishnu orNarayanais the one supreme God. The belief in the supremacy of Vishnu is based upon the many avatars (incarnations) of Vishnu listed in thePuranictexts, which differs from other Hindu deities such asGanesha,Surya,orDurga.To the devotees of theSri Vaishnava Sampradaya,"Lord Vishnu is the Supreme Being and the foundation of all existence."[94]Lakshmi, his consort, is described to act as the mediatrix between Vishnu and his devotees, intervening to offer her grace and forgiveness.[95][96]According to Vedanta Desika,the supreme divine coupleLakshmi Narayanapervades and transcends the entire universe, which is described to be their body. They are described to support all life, both material and spiritual.[97]In this manner, Lakshmi is conceived to be the supreme mother and Narayana as the supreme father of creation.[98]

Krishna

In the Krishnaism group of Vaishnavism traditions, such as theNimbarka Sampradaya(the first Krishnaite Sampradaya developed byNimbarkac. 7th century CE),Ekasarana Dharma,Gaudiya Vaishnavism,Mahanubhava,Rudra Sampradaya(Pushtimarg),Vaishnava-Sahajiya,andWarkari,devotees worship Krishna as the One Supreme form ofGodand source of all avatars,Svayam Bhagavan.[4][100]

Krishnaism is often also called Bhagavatism—perhaps the earliest Krishnite movement was Bhagavatism with Krishna-Vasudeva(about 2nd century BCE)[40]—after theBhagavata Puranawhich asserts that Krishna is "Bhagavan Himself," and subordinates to itself all other forms:Vishnu,Narayana,Purusha,Ishvara,Hari,Vasudeva,Janardanaetc.[101]

Krishna is often described as having the appearance of a dark-skinned person and is depicted as a young cowherd boy playing afluteor as a youthful prince giving philosophical direction and guidance, as in theBhagavad Gita.[102]

Krishna is also worshiped across many other traditions of Hinduism. Krishna and the stories associated with him appear across a broad spectrum of different Hinduphilosophicaland theological traditions, where it is believed thatGodappears to his devoted worshippers in many different forms, depending on their particular desires. These forms include the differentavatarasof Krishna described in traditionalVaishnavatexts, but they are not limited to these. Indeed, it is said that the different expansions of theSvayam bhagavanare uncountable and they cannot be fully described in the finite scriptures of any one religious community.[103][104]Many of theHindu scripturessometimes differ in details reflecting the concerns of a particular tradition, while some core features of the view on Krishna are shared by all.[105]

Radha Krishna

Radha Krishna is the combination of both the feminine as well as the masculine aspects of God. Krishna is often referred asSvayam bhagavaninGaudiya Vaishnavismtheology andRadhais Krishna's internal potency and supreme beloved.[106]With Krishna, Radha is acknowledged as the supreme goddess, for it is said that she controls Krishna with her love.[107]It is believed that Krishna enchants the world, but Radha enchants even him. Therefore, she is the supreme goddess of all.[108][109]Radha and Krishna are avatars ofLakshmiandVishnurespectively. In the region of India called Braj, Radha and Krishna are worshipped together, and their separation cannot even be conceived. And, some communities ascribe more devotional significance to Radha.[110]

While there are much earlier references to the worship of this form of God, it is sinceJayadevawrote the poemGita Govindain the twelfth century CE, that the topic of the spiritual love affair between the divine Krishna and his consort Radha, became a theme celebrated throughout India.[111]It is believed that Krishna has left the "circle" of therasa danceto search for Radha. The Chaitanya school believes that the name and identity of Radha are both revealed and concealed in the verse describing this incident inBhagavata Purana.[112]It is also believed that Radha is not just one cowherd maiden, but is the origin of all thegopis,or divine personalities that participate in therasadance.[113]

Avatars

According to The Bhagavata Purana, there are twenty-two avatars of Vishnu, includingRamaandKrishna.The Dashavatara is a later concept.[38]

Vyuhas

The Pancaratrins follow thevyuhas doctrine, which says that God has four manifestations (vyuhas), namely Vasudeva, Samkarsana, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha. These four manifestations represent "the Highest Self, the individual self, mind, and egoism."[38]

Restoration of dharma

Vaishnavism theology has developed the concept of avatar (incarnation) around Vishnu as the preserver or sustainer. His avataras, asserts Vaishnavism, descend to empower the good and fight evil, thereby restoringdharma.This is reflected in the passages of the ancientBhagavad Gitaas:[114][115]

Whenever righteousness wanes and unrighteousness increases I send myself forth.

For the protection of the good and for the destruction of evil,

and for the establishment of righteousness,

I come into being age after age.

In Vaishnava theology, such as is presented in theBhagavata Puranaand thePancaratra,whenever the cosmos is in crisis, typically because the evil has grown stronger and has thrown the cosmos out of its balance, an avatar of Vishnu appears in a material form, to destroy evil and its sources, and restore the cosmic balance between the everpresent forces of good and evil.[114][90]The most known and celebrated avatars of Vishnu, within the Vaishnavism traditions of Hinduism, areKrishna,Rama,NarayanaandVasudeva.These names have extensive literature associated with them; each has its own characteristics, legends, and associated arts.[114]TheMahabharata,for example, includes Krishna, while theRamayanaincludes Rama.[16]

Texts

The Vedas, the Upanishads, theBhagavad Gita,and theAgamasare the scriptural sources of Vaishnavism.[26][118][119]The Bhagavata Purana is a revered and widely celebrated text, parts of which, a few scholars such as Dominic Goodall, include as a scripture.[118]Other important texts in the tradition include the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, as well as texts by varioussampradayas(denominations within Vaishnavism). In many Vaishnava traditions, Krishna is accepted as a teacher whose teachings are in theBhagavad Gitaand theBhagavata Purana.[35][note 2]

Scriptures

Vedas and Upanishads

Vaishnavism, just like all Hindu traditions, considers theVedasas the scriptural authority.[120][121]All traditions within Vaishnavism consider theBrahmanas,theAranyakasand theUpanishadsembedded within the four Vedas asSruti,while Smritis, which include all the epics, the Puranas and its Samhitas, states Mariasusai Dhavamony, are considered as "exegetical or expository literature" of the Vedic texts.[121]

The Vedanta schools ofHindu philosophy,which interpreted the Upanishads and theBrahma Sutra,provided the philosophical foundations of Vaishnavism. Due to the ancient and archaic language of the Vedic texts, interpretations varied among different schools, leading to differences between the denominations (sampradayas) of Vaishnavism.[122]These interpretations have created different traditions within Vaishnavism, from dualistic (Dvaita) Vedanta ofMadhvacharya,[123]to nondualistic (Advaita) Vedanta ofMadhusudana Sarasvati.[124]

Axiologyin a Vaishnava Upanishad

Thecharity or giftis the armour in the world,

All beings live on the gift of the other,

Through gifts strangers become friends,

Through gifts, they ward off difficulties,

On gifts and giving, everything rests,

That is why charity is the highest.

Vaishnava Upanishads

Along with the reverence and exegetical analysis of the ancientPrincipal Upanishads,Vaishnava-inspired scholars authored 14 Vishnu avatar-focussed Upanishads that are called the Vaishnava Upanishads.[127]These are considered part of 95 minor Upanishads in theMuktikāUpanishadic corpus of Hindu literature.[127][128]The earliest among these were likely composed in 1st millennium BCE, while the last ones in the late medieval era.[129][130][131]

All of the Vaishnava Upanishads either directly reference and quote from the ancient Principal Upanishads or incorporate some ideas found in them; most cited texts include theBrihadaranyaka Upanishad,Chandogya Upanishad,Katha Upanishad,Isha Upanishad,Mundaka Upanishad,Taittiriya Upanishadand others.[132][133]In some cases, they cite fragments from theBrahmanaandAranyakalayers of theRigvedaand theYajurveda.[132]

The Vaishnava Upanishads present diverse ideas, ranging frombhakti-style theistic themes to a synthesis of Vaishnava ideas with Advaitic, Yoga, Shaiva and Shakti themes.[132][134]

| Vaishnava Upanishad | Vishnu Avatar | Composition date | Topics | Reference |

| Mahanarayana Upanishad | Narayana | 6AD - 100 CE | Narayana, Atman, Brahman, Rudra, Sannyasa | [132][134] |

| Narayana Upanishad | Narayana | Medieval | Mantra, Narayana is one without a second, eternal, same as all gods and universe | [135] |

| Rama Rahasya Upanishad | Rama | ~17th century CE | Rama, Sita, Hanuman, Atman, Brahman, mantra | [136][137] |

| Rama tapaniya Upanishad | Rama | ~11th to 16th century | Rama, Sita, Atman, Brahman, mantra, sannyasa | [136][138] |

| Kali-Santarana Upanishad | Rama, Krishna | ~14th century | Hare Rama Hare Krishna mantra | [139] |

| Gopala Tapani Upanishad | Krishna | before the 14th century | Krishna, Radha, Atman, Brahman, mantra, bhakti | [140] |

| Krishna Upanishad | Krishna | ~12th-16th century | Rama predicting Krishna birth, symbolism, bhakti | [141] |

| Vasudeva Upanishad | Krishna, Vasudeva | ~2nd millennium | Brahman, Atman, Vasudeva, Krishna,Urdhva Pundra,Yoga | [142] |

| Garuda Upanishad | Vishnu | Medieval | The kite-like birdvahana(vehicle) of Vishnu | [143][144] |

| Hayagriva Upanishad | Hayagriva | medieval, after the 10th century CE | Mahavakya of Principal Upanishads, Pancaratra, Tantra | [133][145] |

| Dattatreya Upanishad | Narayana, Dattatreya | 14th to 15th century | Tantra, yoga, Brahman, Atman, Shaivism, Shaktism | [146] |

| Tarasara Upanishad | Rama, Narayana | ~11th to 16th century | Om, Atman, Brahman, Narayana, Rama, Ramayana | [147] |

| Avyakta Upanishad | Narasimha | before the 7th century | Primordial nature, cosmology,Ardhanarishvara,Brahman, Atman | [130] |

| Nrisimha Tapaniya Upanishad | Narasimha | before the 7th century CE | Atman, Brahman, Advaita, Shaivism, Avatars of Vishnu,Om | [148] |

Bhagavad Gita

TheBhagavad Gitais a central text in Vaishnavism, and especially in the context of Krishna.[149][150][151]TheBhagavad Gitais an important scripture not only within Vaishnavism, but also to other traditions of Hinduism.[152][153]It is one of three important texts of theVedantaschool ofHindu philosophy,and has been central to all Vaishnavism sampradayas.[152][154]

TheBhagavad Gitais a dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna, and presents Bhakti, Jnana and Karma yoga as alternate ways to spiritual liberation, with the choice left to the individual.[152]The text discussesdharma,and its pursuit as duty without craving for fruits of one's actions, as a form of spiritual path to liberation.[155]The text, state Clooney and Stewart, succinctly summarizes the foundations of Vaishnava theology that the entire universe exists within Vishnu, and all aspects of life and living is not only a divine order but divinity itself.[156]Bhakti, in Bhagavad Gita, is an act of sharing, and a deeply personal awareness of spirituality within and without.[156]

TheBhagavad Gitais a summary of the classical Upanishads and Vedic philosophy, and closely associated with the Bhagavata and related traditions of Vaishnavism.[157][158]The text has been commented upon and integrated into diverse Vaishnava denominations, such as by the medieval era Madhvacharya'sDvaitaVedanta school and Ramanuja'sVishishtadvaitaVedanta school, as well as 20th century Vaishnava movements such as the Hare Krishna movement by His Divine GraceA. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.[159]

Vaishnava Agamas

ThePancaratraSamhitas(literally, five nights) is a genre of texts where Vishnu is presented as Narayana and Vasudeva, and this genre of Vaishnava texts is also known as the VaishnavaAgamas.[24][25]Its doctrines are found embedded in the stories within the Narayaniya section of theMahabharata.[160]Narayana is presented as the ultimate unchanging truth and reality (Brahman), who pervades the entirety of the universe and is asserted to be the preceptor of all religions.[160][161]

The Pancaratra texts present theVyuhastheory of avatars to explain how the absolute reality (Brahman) manifests into material form of ever changing reality (Vishnu avatar).[160][162]Vasudeva, state the Pancaratra texts, goes through a series of emanations, where new avatars of him appear. This theory of avatar formation syncretically integrates the theories of evolution of matter and life developed by theSamkhyaschool of Hindu philosophy.[163][162]These texts also present cosmology, methods of worship, tantra, Yoga and principles behind the design and building of Vaishnava temples (Mandira nirmana).[163][164][165]These texts have guided religiosity and temple ceremonies in many Vaishnava communities, particularly in South India.[163]

ThePancaratra Samhitasare tantric in emphasis, and at the foundation of tantric Vaishnava traditions such as the Sri Vaishnava tradition.[166][167]They complement and compete with the vedic Vaishnava traditions such as the Bhagavata tradition, which emphasize the more ancient Vedic texts, ritual grammar and procedures.[166][165]While the practices vary, the philosophy of Pancaratra is primarily derived from the Upanishads, its ideas synthesize Vedic concepts and incorporate Vedic teachings.[168][169]

The three most studied texts of this genre of Vaishnava religious texts arePaushkara Samhita,Sattvata SamhitaandJayakhya Samhita.[163][170]The other important Pancaratra texts include theLakshmi TantraandAhirbudhnya Samhita.[25][171]Scholars place the start of this genre of texts to about the 7th or 8th century CE, and later.[163][172]

Other texts

Mahabharata and Ramayana

The twoIndianepics,theMahabharataand theRamayanapresent Vaishnava philosophy and culture embedded in legends and dialogues.[173]The epics are considered the fifth Veda in Hindu culture.[174]The Ramayana describes the story ofRama,an avatara of Vishnu, and is taken as a history of the 'ideal king', based on the principles ofdharma,morality and ethics.[175]Rama's wifeSita,his brotherLakshman,with his devotee and followerHanumanall play key roles within the Vaishnava tradition as examples of Vaishnava etiquette and behaviour.Ravana,the evil king and villain of the epic, is presented as an epitome ofadharma,playing the opposite role of how not to behave.[176]

The Mahabharata is centered aroundKrishna,presents him as the avatar of transcendental supreme being.[177]The epic details the story of a war between good and evil, each side represented by two families of cousins with wealth and power, one depicted as driven by virtues and values while other by vice and deception, with Krishna playing pivotal role in the drama.[178]The philosophical highlight of the work is the Bhagavad Gita.[179][120]

Puranas

ThePuranasare an important source of entertaining narratives and histories, states Mahony, that are embedded with "philosophical, theological and mystical modes of experience and expression" as well as reflective "moral and soteriological instructions".[182]

More broadly, the Puranic literature is encyclopedic,[183][184]and it includes diverse topics such ascosmogony,cosmology,genealogies of gods, goddesses, kings, heroes, sages, and demigods, folk tales, travel guides and pilgrimages,[185]temples, medicine, astronomy, grammar, mineralogy, humor, love stories, as well as theology and philosophy.[186][187][188]The Puranas were a living genre of texts because they were routinely revised,[189]their content is highly inconsistent across the Puranas, and each Purana has survived in numerous manuscripts which are themselves inconsistent.[190][191]The Hindu Puranas are anonymous texts and likely the work of many authors over the centuries.[190][191]

Of the 18 Mahapuranas (great Puranas), many have titles based on one of the avatars of Vishnu. However, quite many of these are actually, in large part, Shiva-related Puranas, likely because these texts were revised over their history.[192]Some were revised into Vaishnava treatises, such as theBrahma Vaivarta Purana,which originated as a Puranic text dedicated to theSurya(Sun god). Textual cross referencing evidence suggests that in or after 15th/16th century CE, it went through a series of major revisions, and almost all extant manuscripts ofBrahma Vaivarta Puranaare now Vaishnava (Krishna) bhakti oriented.[193]Of the extant manuscripts, the main Vaishnava Puranas areBhagavata Purana,Vishnu Purana,Nāradeya Purana,Garuda Purana,Vayu PuranaandVaraha Purana.[194]TheBrahmanda Puranais notable for theAdhyatma-ramayana,a Rama-focussed embedded text in it, which philosophically attempts to synthesizeBhaktiin god Rama withShaktismandAdvaita Vedanta.[195][196][197]While an avatar of Vishnu is the main focus of the Puranas of Vaishnavism, these texts also include chapters that revere Shiva, Shakti (goddess power), Brahma and a pantheon of Hindu deities.[198][199][200]

The philosophy and teachings of the Vaishnava Puranas arebhaktioriented (often Krishna, but Rama features in some), but they show an absence of a "narrow, sectarian spirit". To its bhakti ideas, these texts show a synthesis ofSamkhya,YogaandAdvaita Vedantaideas.[201][202][203]

InGaudiya Vaishnava,Vallabha SampradayaandNimbarka sampradaya,Krishna is believed to be a transcendent, Supreme Being and source of all avatars in the Bhagavata Purana.[204]The text describes modes of loving devotion to Krishna, wherein his devotees constantly think about him, feel grief and longing when Krishna is called away on a heroic mission.[205]

Practices

Bhakti

TheBhakti movementoriginated among Vaishnavas ofSouth Indiaduring the 7th-century CE,[207]spread northwards from Tamil Nadu throughKarnatakaandMaharashtratowards the end of 13th-century,[208]and gained wide acceptance by the fifteenth-century throughout India during an era of political uncertainty and Hindu-Islam conflicts.[209][210][211]

TheAlvars,which literally means "those immersed in God", were Vaishnava poet-saints who sang praises of Vishnu as they travelled from one place to another.[212]They established temple sites such asSrirangam,and spread ideas about Vaishnavism. Their poems, compiled asDivya Prabhandham,developed into an influential scripture for the Vaishnavas. TheBhagavata Purana's references to the South Indian Alvar saints, along with its emphasis onbhakti,have led many scholars to give it South Indian origins, though some scholars question whether this evidence excludes the possibility thatbhaktimovement had parallel developments in other parts of India.[213][214]

Vaishnava bhakti practices involve loving devotion to a Vishnu avatar (often Krishna), an emotional connection, a longing and continuous feeling of presence.[215]All aspects of life and living is not only a divine order but divinity itself in Vaishnava bhakti.[156]Community practices such as singing songs together (kirtanorbhajan), praising or ecstatically celebrating the presence of god together, usually inside temples, but sometimes in open public are part of varying Vaishnava practices.[216]Other practical methods includes devotional practices such as chanting mantras (japa), performing rituals, and engaging in acts of service (seva) within the community.[217]These help Vaishnavas socialize and form a community identity.[218]

Tilaka

Right: A Shaiva Hindu with Tilaka (Tripundra)[220][221]

Vaishnavas mark their foreheads withtilakamade up of Chandana, either as a daily ritual, or on special occasions. The different Vaishnava sampradayas each have their own distinctivestyle of tilaka,which depicts thesiddhantaof their particular lineage. The general tilaka pattern is of a parabolic shape resembling the letter U or two or more connected vertical lines on and another optional line on the nose resembling the letter Y, in which the two parallel lines represent the Lotus feet of Krishna and the bottom part on the nose represents thetulsileaf.[222][223]

Initiation

In tantric traditions of Vaishnavism, during the initiation (diksha) given by aguruunder whom they are trained to understand Vaishnava practices, the initiates accept Vishnu as supreme. At the time of initiation, the disciple is traditionally given a specificmantra,which the disciple will repeat, either out loud or within the mind, as an act of worship to Vishnu or one of his avatars. The practice of repetitive prayer is known asjapa.

In the Gaudiya Vaishnava group, one who performs an act of worship with the name of Vishnu or Krishna can be considered a Vaishnava by practice, "Who chants the holy name of Krishna just once may be considered a Vaishnava."[224]

Pilgrimage sites

indicatesChar Dham

indicatesChar Dham

Important sites of pilgrimage for Vaishnavas includeGuruvayur Temple,Srirangam,Kanchipuram,Vrindavan,Mathura,Ayodhya,Tirupati,Pandharpur (Vitthal),Puri (Jaggannath),Nira Narsingpur (Narasimha),Mayapur,Nathdwara,Dwarka,Udipi (Karnataka),Shree Govindajee Temple (Imphal),Govind Dev Ji Temple (Jaipur)andMuktinath.[225][226]

Holy places

Vrindavanais considered to be a holy place by several traditions of Krishnaism. It is a center of Krishna worship and the area includes places likeGovardhanaandGokulaassociated with Krishna from time immemorial. Many millions ofbhaktasor devotees ofKrishnavisit these places of pilgrimage every year and participate in a number of festivals that relate to the scenes from Krishna's life on Earth.[35][note 4]

On the other hand,Golokais considered the eternal abode ofKrishna,Svayam bhagavanaccording to someVaishnavaschools, includingGaudiya Vaishnavismand theSwaminarayan Sampradaya.The scriptural basis for this is taken inBrahma SamhitaandBhagavata Purana.[227]

Traditions

Four sampradayas and other traditions

The Vaishnavism traditions may be grouped within foursampradayas,each exemplified by a specific Vedic personality. They have been associated with a specific founder, providing the following scheme: Sri Sampradaya (Ramanuja), Brahma Sampradaya (Madhvacharya),[228]Rudra Sampradaya (Vishnuswami,Vallabhacharya),[229]Kumaras Sampradaya (Nimbarka).[230][note 5]These four sampradayas emerged in early centuries of the 2nd millennium CE, by the 14th century, influencing and sanctioning theBhakti movement.[68]

The philosophical systems of Vaishnava sampradayas range from qualifiedmonisticVishishtadvaitaof Ramanuja, to theisticDvaitaof Madhvacharya, to purenondualisticShuddhadvaitaof Vallabhacharya. They all revere an avatar of Vishnu, but have varying theories on the relationship between the soul (jiva) andBrahman,[182][233]on the nature of changing and unchanging reality, methods of worship, as well as on spiritual liberation for the householder stage of life versussannyasa(renunciation) stage.[20][21]

Beyond the four major sampradayas, the situation is more complicated,[234]with the Vaikhanasas being much older[235]than those four sampradayas, and a number of additional traditions and sects which originated later,[236]or aligned themselves with one of those four sampradayas.[231]Krishna sampradayas continued to be founded late into late medieval and during theMughal Empireera, such as theRadha Vallabh Sampradaya,Haridasa,Gaudiyaand others.[237]

Traditions List

Early traditions

Bhagavats

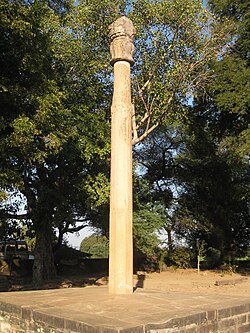

The Bhagavats were the early worshippers of Krishna, the followers ofBhagavat,the Lord, in the person ofKrishna,Vasudeva,VishnuorBhagavan.[245]The termbhagavatamay have denoted a general religious tradition or attitude of theistic worship which prevailed until the 11th century, and not a specific sect,[235][246]and is best known as a designation for Vishnu-devotees.[246]The earliest scriptural evidence of Vaishnava bhagavats is an inscription from 115 BCE, in whichHeliodoros,ambassador of the Greco-Bactrian king Amtalikita, says that he is a bhagavata of Vasudeva.[247]It was supported by the Guptas, suggesting a widespread appeal, in contrast to specific sects.[245]

| Heliodorus pillar | |

|---|---|

Heliodorus pillarinVidisha,India. | |

| Period/culture | late 2nd century BCE |

| Place | Vidisha,Madhya Pradesh,India. |

| Present location | Vidisha,India |

Pancaratra

ThePāñcarātrais the tradition of Narayana-worship.[160]The termpāñcarātrameans "five nights," frompañca,"five," andrātra,"nights,"[248][160]and may be derived from the "five night sacrifice" as described in theSatapatha Brahmana,which narrates how Purusa-Narayana intends to become the highest being by performing a sacrifice which lasts five nights.[160]

TheNarayaniyasection of the Mahabharata describes the ideas of thePāñcarātras.[160]Characteristic is the description of the manifestation of the Absolute through a series of manifestations, from thevyuhamanifestations of Vasudeva and pure creation, through thetattvasof mixed creation into impure or material creation.[24]

ThePāñcarātra Samhitasdeveloped from the 7th or 8th century onward, and belongs toAgamicor Tantras,[249][163]setting them at odds with vedic orthodoxy.[166]Vishnu worshipers in south India still follow the system of Pancharatra worship as described in these texts.[163]

Although thePāñcarātraoriginated in north India, it had a strong influence on south India, where it is closely related with the Sri Vaishnava tradition. According to Welbon, "Pāñcarātracosmological and ritual theory and practice combine with the unique vernacular devotional poetry of the Alvars, and Ramanuja, founder of the Sri Vaishnava tradition, propagatedPāñcarātraideas. "[250]Ramananda was also influenced byPāñcarātraideas through the influence of Sri Vaishnavism, wherebyPāñcarātrare-entered north India.[250]

Vaikhanasas

The Vaikhanasas are associated with thePāñcarātra,but regard themselves as a Vedic orthodox sect.[235][251]ModernVaikhanasasreject elements of thePāñcarātraandSri Vaishnavatradition, but the historical relationship with the orthodoxVaikhanasain south India is unclear.[citation needed]TheVaikhanasasmay have resisted the incorporation of the devotic elements of the Alvar tradition, while thePāñcarātraswere open to this incorporation.[250]

Vaikhanasas have their own foundational text, theVaikhanasasmarta Sutra,which describes a mixture of Vedic and non-Vedic ritual worship.[235]The Vaikhanasas became chief priests in a lot of south Indian temples, where they still remain influential.[235]

Early medieval traditions

Smartism

The Smarta tradition developed during the (early) Classical Period of Hinduism around the beginning of the Common Era, when Hinduism emerged from the interaction between Brahmanism and local traditions.[252][253]According to Flood, Smartism developed and expanded with thePuranasgenre of literature.[254]By the time of Adi Shankara,[252]it had developed thepancayatanapuja,the worship of five shrines with five deities, all treated as equal, namelyVishnu,Shiva,Ganesha,SuryaandDevi(Shakti),[254]"as a solution to varied and conflicting devotional practices."[252]

Traditionally, Sri Adi Shankaracharya (8th century) is regarded as the greatest teacher and reformer of the Smarta.[255][256]According to Hiltebeitel, Adi Shankara Acharya established the nondualist interpretation of the Upanishads as the touchstone of a revivedsmartatradition.[252][note 9]

Alvars

The Alvars, "those immersed in god," were twelve[210]Tamilpoet-saints ofSouth Indiawho espousedbhakti(devotion) to theHindugodVishnuor hisavatarKrishnain their songs of longing, ecstasy and service.[257]The Alvars appeared between the 5th century to the 10th century CE, though the Vaishnava tradition regards the Alvars to have lived between 4200 BCE - 2700 BCE.

The devotional writings of Alvars, composed during the early medieval period ofTamil history,are key texts in thebhakti movement.They praised theDivya Desams,108 "abodes" (temples) of the Vaishnava deities.[258]The collection of their hymns is known as theDivya Prabandha.Their Bhakti-poems has contributed to the establishment and sustenance of a culture that opposed the ritual-oriented Vedic religion and rooted itself in devotion as the only path for salvation.[259]

Contemporary traditions

Gavin Flood mentions five most important contemporary Vaishnava orders.[236]

Nimbarka Sampradaya

Nimbarka Sampradaya, also called Kumara Sampradaya is one of the four bonafied Vaishnavism tradition. It worshipKrishnawith his chief consort,Radha.The tradition was founded byNimbarkacharyaaround 7th CE-12 CE. Nimbarka's philosphical position is dualistic monism and he centered all his devotion to the unified form of the divine coupleRadha Krishnain Sakhya bhav.[260][261][262]

Sri Vaishnavism

Sri Vaishnavism is one of the major denomination within Vaishnavism that originated inSouth India,adopting the prefixSrias an homage to Vishnu's consort,Lakshmi.[263]The Sri Vaishnava community consists of both Brahmans and non-Brahmans.[264]It existed along with a larger Purana-based Brahamanical worshippers of Vishnu, and non-Brahmanical groups who worshipped and also adhered by non-Vishnu village deities.[264]The Sri Vaishnavism movement grew with its social inclusiveness, where emotional devotion to the personal god (Vishnu) has been open without limitation to gender or caste.[72][note 10]

The most striking difference between Sri Vaishnavas and other Vaishnava groups lies in their interpretation of Vedas. While other Vaishnava groups interpret Vedic deities like Indra, Savitar, Bhaga, Rudra, etc. to be same as their Puranic counterparts, Sri Vaishnavas consider these to be different names/roles/forms ofNarayana,claiming that the entire Veda is dedicated for Vishnu-worship alone. Sri Vaishnavas have remodelled Pancharatra homas like the Sudarshana homa to include Vedic Suktas in them, thus giving them a Vedic outlook.[citation needed]

Sri Vaishnavism developed inTamilakamin the 10th century.[266]It incorporated two different traditions, namely the tantric Pancaratra tradition, and the Puranic Vishnu worship of northern India with their abstract Vedantic theology, and the southern bhakti tradition of the Alvars of Tamil Nadu with their personal devotion.[266][72]The tradition was founded byNathamuni(10th century), who along withYamunacharya,combined the two traditions and gave the tradition legitimacy by drawing on the Alvars.[238]Its most influential leader wasRamanuja(1017-1137), who developed theVishistadvaita( "qualified non-dualism" ) philosophy.[267]Ramanuja challenged the then dominantAdvaita Vedantainterpretation of the Upanishads and Vedas, by formulating the Vishishtadvaita philosophy foundations for Sri Vaishnavism from Vedanta.[72]

Sri Vaishnava includes the ritual and temple life in the tantra traditions ofPancharatra,emotional devotion to Vishnu, and the contemplative formbhakti,in the context of householder social and religious duties.[72]The tantric rituals refers to techniques and texts recited during worship, and these include Sanskrit and Tamil texts in South Indian Sri Vaishnava tradition.[265]According to Sri Vaishnavism theology,mokshacan be reached by devotion and service to the Lord and detachment from the world. Whenmokshais reached, the cycle of reincarnation is broken and the soul is united with Vishnu after death, though maintaining their distinctions inVaikuntha,Vishnu's abode.[268]Moksha can also be reached by total surrender andsaranagati,an act of grace by the Lord.[269]Ramanuja's Sri Vaishnavism subscribes tovidehamukti(liberation in afterlife), in contrast tojivanmukti(liberation in this life) found in other traditions within Hinduism, such as the Smarta and Shaiva traditions.[270]

Two hundred years after Ramanuja, the Sri Vaishnava tradition split into theVadakalai(northern art) andTenkalai(southern art) sects. TheVadakalairegard the Vedas as the greatest source of religious authority, emphasising bhakti through devotion to temple-icons, while theTenkalairely more on Tamil scriptures and total surrender to God.[269]The philosophy of Sri Vaishnavism is adhered to and disseminated by theIyengarcommunity.[271]

Sadh Vaishnavism

Sadh Vaishnavism is one of the major denominations within Vaishnavism that originated inKarnataka,South India,adopting the prefixSadhwhich means 'true'. Madhvacharya named his Vaishnavism as Sadh Vaishnavism in order to distinguish it from the Sri Vaishnavism of Ramanuja. Sadh Vaishnavism was founded by the thirteenth-century philosopherMadhvacharya.[272][273]It is a movement inHinduismthat developed during its classical period around the beginning of the Common Era. Philosophically, Sadh Vaishnavism is aligned withDvaita Vedanta,and regardsMadhvacharyaas its founder or reformer.[274]The tradition traces its roots to the ancientVedasandPancharatratexts. The Sadh Vaishnavism or Madhva Sampradaya is also referred to as theBrahma Sampradaya,referring to its traditional origins in the succession of spiritual masters (gurus) have originated fromBrahma.[275]

In Sadh Vaishnavism, the creator is superior to the creation, and hencemokshacomes only from the grace ofVishnu,but not from effort alone.[276]Compared to other Vaishnava schools which emphasize only on Bhakti, Sadh Vaishnavism regardsJnana,BhaktiandVairagyaas necessary steps for moksha. So in Sadh Vaishnavism —Jnana Yoga,Bhakti YogaandKarma Yogaare equally important in order to attain liberation. TheHaridasamovement, a bhakti movement originated fromKarnatakais a sub-branch of Sadh Vaishnavism.[277]Sadh Vaishnavism worships Vishnu as the highest Hindu deity and regardsMadhva,whom they consider to be an incarnation of Vishnu's son,Vayu,as an incarnate saviour.[278]Madhvism regards Vayu asVishnu's agent in this world, andHanuman,Bhima,andMadhvacharyato be his three incarnations; for this reason, the roles of Hanuman in theRamayanaand Bhima in theMahabharataare emphasised, and Madhvacharya is particularly held in high esteem.[279]Vayu is prominently shown by Madhva in countless texts.[280][281]

The most striking difference between Sadh Vaishnavas and other Vaishnava groups lies in their interpretation of Vedas and their way of worship. While other Vaishnava groups deny the worship of Vedic deities such as Rudra, Indra etc., Sadh Vaishnavas worship all devatas including Lakshmi, Brahma, Vayu, Saraswati, Shiva (Rudra), Parvati, Indra, Subrahmanya and Ganesha as per "Taratamya". In fact, Madhvacharya in his Tantra Sara Sangraha clearly explained how to worship all devatas. In many of his works Madhvacharya also explained the Shiva Tattva, the procedure to worship PanchamukhaShiva(Rudra), thePanchakshari Mantraand even clearly explained why everyone should worship Shiva. Many prominent saints and scholars of Sadh Vaishnavism such asVyasatirthacomposed "Laghu Shiva Stuti",Narayana PanditacharyacomposedShiva StutiandSatyadharma Tirthawrote a commentary onSri Rudram(Namaka Chamaka) in praise of Shiva. Indologist B. N. K. Sharma says These are positive proofs of the fact that Madhvas are not bigots opposed to the worship of Shiva.[282]Sharma says, Sadh Vaishnavism is more tolerant and accommodative of the worship of other gods such asShiva,Parvati,Ganesha,Subrahmanyaand others of the Hindu pantheon compared to other Vaishnava traditions. This is the reason whyKanaka Dasathough under the influence of Tathacharya in his early life did not subscribe wholly to the dogmas ofSri Vaishnavismagainst the worship ofShivaetc., and later became the disciple ofVyasatirtha.[283]

The influence of Sadh Vaishnavism was most prominent on the Chaitanya school ofBengalVaishnavism, whose devotees later started the devotional movement on the worship ofKrishnaasInternational Society for Krishna Consciousness(ISKCON) - known colloquially as theHare Krishna Movement.[284]It is stated thatChaitanya Mahaprabhu(1496–1534) was a disciple of Isvara Puri, who was a disciple of Madhavendra Puri, who was a disciple of Lakshmipati Tirtha, was a disciple ofVyasatirtha(1469–1539), of the Sadh Vaishnava Sampradaya of Madhvacharya.[285]The Madhva school of thought also had a huge impact on Gujarat Vaishnava culture.[286]The famous bhakti saint of Vallabha Sampradaya,Swami Haridaswas a direct disciple ofPurandara Dasaof Madhva Vaishnavism. Hence Sadh Vaishnavism also have some influence on Vallabha's Vaishnavism as well.[287]

Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Gaudiya Vaishnavism, also known as Chaitanya Vaishnavism[288]and Hare Krishna, was founded byChaitanya Mahaprabhu(1486–1533) in India. "Gaudiya" refers to theGauḍa region(present dayBengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism meaning "the worship ofVishnuorKrishna".Its philosophical basis is primarily that of theBhagavad GitaandBhagavata Purana.

The focus of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is the devotional worship (bhakti) ofRadhaandKrishna,and their many divineincarnationsas the supreme forms ofGod,Svayam Bhagavan.Most popularly, this worship takes the form of singing Radha and Krishna'sholynames, such as "Hare", "Krishna" and "Rama", most commonly in the form of theHare Krishna (mantra),also known askirtan.It sees the many forms of Vishnu or Krishna as expansions or incarnations of the one Supreme God.

After its decline in the 18-19th century, it was revived in the beginning of the 20th century due to the efforts ofBhaktivinoda Thakur.His son SrilaBhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakurafounded sixty-four Gaudiya Matha monasteries in India, Burma and Europe.[289]Thakura's discipleSrila Prabhupadawent to the west and spread Gaudiya Vaishnavism by theInternational Society for Krishna Consciousness(ISKCON).

TheManipuri Vaishnavismis a regional variant of Gaudiya Vaishnavism with a culture-forming role among theMeitei peoplein the north-eastern Indian state ofManipur.[290]There, after a short period ofRamaismpenetration, Gaudiya Vaishnavism spread in the early 18th century, especially from beginning its second quarter. RajaGharib Nawaz (Pamheiba)was initiated into the Chaitanya tradition. Most devotee ruler and propagandist of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, under the influence ofNatottama Thakura's disciples, was rajaBhagyachandra,who has visited the holy for the ChaytanyaitsNabadwip.[291]

Warkari tradition

The Warkari sampradaya is a non-Brahamanical[note 11]bhakti tradition which worshipsVithoba,also known as Vitthal, who is regarded as a form of Krishna/Vishnu. Vithoba is often depicted as a dark young boy, standing arms akimbo on a brick, sometimes accompanied by his main consort Rakhumai (a regional name of Krishna's wifeRukmini). The Warkari-tradition is geographically associated with the Indian state ofMaharashtra.[292]

The Warkari movement includes a duty-based approach towards life, emphasizing moral behavior and strict avoidance ofalcoholandtobacco,the adoption of a strictlacto-vegetariandiet and fasting onEkadashiday (twice a month), self-restraint (brahmacharya) duringstudentlife, equality and humanity for all rejecting discrimination based on thecaste systemor wealth, the reading ofHindu texts,the recitation of theHaripathevery day and the regular practice ofbhajanandkirtan.The most important festivals of Vithoba are held on the eleventh (ekadashi) day of the lunar months "Shayani Ekadashiin the month ofAshadha,andPrabodhini Ekadashiin the month ofKartik.[292]

The Warkari poet-saints are known for their devotional lyrics, theabhang,dedicated to Vithoba and composed inMarathi.Other devotional literature includes the Kannada hymns of the Haridasa, and Marathi versions of the genericaartisongs associated with rituals of offering light to the deity. Notable saints andgurusof the Warkaris includeJñāneśvar,Namdev,Chokhamela,Eknath,andTukaram,all of whom are accorded the title ofSant.

Though the origins of both his cult and his main temple are debated, there is clear evidence that they already existed by the 13th century. VariousIndologistshave proposed a prehistory for Vithoba worship where he was previously ahero stone,a pastoral deity, a manifestation ofShiva,aJain saint,or even all of these at various times for various devotees.

Ramanandi tradition

The Ramanandi Sampradaya, also known as the Ramayats or the Ramavats,[293]is one of the largest and most egalitarian Hindu sects in India, around theGanges Plain,and Nepal today.[294]It mainly emphasizes the worship ofRama,[293]as well asVishnudirectly and other incarnations.[295]Most Ramanandis consider themselves to be the followers ofRamananda,aVaishnavasaint in medieval India.[296]Philosophically, they are in theVishishtadvaita(IASTViśiṣṭādvaita) tradition.[293]

Its ascetic wing constitutes the largest Vaishnavamonastic orderand may possibly be the largest monastic order in all of India.[297]Rāmānandīascetics rely upon meditation and strict ascetic practices and believe that the grace of god is required for them to achieve liberation.

Northern Sant tradition

Kabirwas a 15th-century Indianmysticpoetandsant,whose writings influenced theBhakti movement,but whose verses are also found in Sikhism's scriptureAdi Granth.[241][298][299]His early life was in a Muslim family, but he was strongly influenced by his teacher, the Hindu bhakti leaderRamananda,he becomes a Vaishnavite with universalist leanings. His followers formed theKabir panth.[241][1][300][298][301]

Dadu Dayal(1544—1603) was a poet-sant fromGujarat,a religious reformer who spoke against formalism and priestcraft. A group of his followers nearJaipur,Rajasthan, forming a Vaishnavite denomination that became known as the Dadu Panth.[1][302]

Other traditions

Odia Vaishnavism

TheOdiaVaishnavism (a.k.a.Jagannathism)—the particular cult of the godJagannath(lit. ''Lord of the Universe'') as the supreme deity, an abstract form of Krishna, thePurushottama,andPara Brahman—was origined in theEarly Middle Ages.[303]Jagannathism was a regional state temple-centered version ofKrishnaism,[304]but can also be regarded as a non-sectarian syncretic Vaishnavite and all-Hindu cult.[305]The notableJagannath templeinPuri,Odisha became particularly significant within the tradition since about 800 CE.[306]

Mahanubhava Sampradaya

The Mahanubhava Sampradaya/Pantha founded inMaharashtraduring the period of 12-13th century. SarvajnaChakradhar SwamiaGujaratiacharya was the main propagator of this Sampradaya. The Mahanubhavas venere Pancha-Krishna( "five Krishnas" ). Mahanubhava Pantha played essential role in the growth ofMarathiliterature.[307]

Sahajiya and Baul tradition

Since 15th century in Bengal andAssamflourishedTantricVaishnava-Sahajiya inspired by Bengali poetChandidas,as well as related to it Baul groups, where Krishna is the inner divine aspect of man and Radha is the aspect of woman.[308]

Ekasarana Dharma

The Ekasarana Dharma was propagated bySrimanta Sankardevin theAssamregion of India.It considersKrishnaas the only God.[309]Satrasare institutional centers associated with the Ekasarana dharma.[310][311]

Radha-vallabha Sampradaya

TheRadha-centered Radha Vallabh Sampradaya founded by theMathurabhakti poet-saintHith Harivansh Mahaprabhuin the 16th century occupies a unique place among other traditions. In its theology, Radha is worshiped as the supreme deity, and Krishna is in a subordinate position.[312]

Pranami Sampradaya

The Pranami Sampradaya (Pranami Panth) emerged in the 17th century inGujarat,based on the Radha-Krishna-focussed syncretic Hindu-Islamicteachings of Devchandra Maharaj and his famous successor, Mahamati Prannath.[313]

Swaminarayan Sampradaya

The Swaminarayan Sampradaya was founded in 1801 inGujaratbySahajanand SwamifromUttar Pradesh,who is worshipped asSwaminarayan,the supreme manifestation of God, by his followers. The first temple built inAhmedabadin 1822.[314]

Vaishnavism and other Hindu tradition table

The Vaishnavism sampradayas subscribe to various philosophies, are similar in some aspects and differ in others. When compared with Shaivism, Shaktism and Smartism, a similar range of similarities and differences emerge.[315]

| Vaishnava Traditions | Shaiva Traditions | Shakta Traditions | Smarta Traditions | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scriptural authority | Vedas and Upanishads | Vedas and Upanishads | Vedas and Upanishads | Vedas and Upanishads | [89][121] |

| Supreme deity | Vishnu asMahavishnuor Krishna asVishwarupa[citation needed] | Shiva asParashiva,[citation needed] | Devi asAdi Parashakti,[citation needed] | None, Varies | [315][316] |

| Creator | Vishnu | Shiva | Devi | Brahman principle | [315][317] |

| Avatar | Key concept | Minor | Significant | Minor | [89][318][319] |

| Monasticlife | Accepts | Recommends | Accepts | Recommends | [89][320][321] |

| Rituals,Bhakti | Affirms | Optional, Varies[322][323][324] | Affirms | Optional[325] | [326] |

| Ahimsaand Vegetarianism | Affirms, Optional, Varies | Recommends,[322]Optional | Optional | Recommends, Optional | [327][328] |

| Free will,Maya,Karma | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | [315] |

| Metaphysics | Brahman(Vishnu) andAtman(Soul, Self) | Brahman (Shiva), Atman | Brahman (Devi), Atman | Brahman, Atman | [315] |

| Epistemology (Pramana) |

|

|

|

|

[330][331][332] |

| Philosophy (Darshanam) | Vishishtadvaita(qualified Non dualism),Dvaita(Dualism), Shuddhadvaita(Pure Non Dualism),Dvaitadvaita(Dualistic Non Dualism), Advaita(Non Dualism),Achintya Bhedabheda(Non Dualistic Indifferentiation) |

Vishishtadvaita,Advaita | Samkhya,Shakti-Advaita | Advaita | [333][334] |

| Salvation (Soteriology) |

Videhamukti,Yoga, champions householder life, Vishnu is soul |

Jivanmukta, Shiva is soul,Yoga, champions monastic life |

Bhakti, Tantra,Yoga | Jivanmukta, Advaita,Yoga, champions monastic life |

[270][335] |

Demography

There is no data available on demographic history or trends for Vaishnavism or other traditions within Hinduism.[336]

Estimates vary on the relative number of adherents in Vaishnavism compared to other traditions of Hinduism.[note 12]Klaus Klostermaierand other scholars estimate Vaishnavism to be the largest Hindu denomination.[338][339][6][note 13]The denominations of Hinduism, states Julius Lipner, are unlike those found in major religions of the world, because Hindu denominations are fuzzy, individuals revere gods and goddessespolycentrically,with many Vaishnava adherents recognizing Sri (Lakshmi), Shiva, Parvati and others reverentially on festivals and other occasions. Similarly, Shaiva, Shakta and Smarta Hindus revere Vishnu.[340][341]

Vaishnavism is one of the major traditions within Hinduism.[342]Large Vaishnava communities exist throughout India, and particularly in Western Indian states, such as westernMadhya Pradesh,Rajasthan,MaharashtraandGujaratand SouthwesternUttar Pradesh.[225][226]Other major regions of Vaishnava presence, particularly after the 15th century, areOdisha,Bengaland northeastern India (Assam,Manipur).[343]Dvaita school Vaishnava have flourished inKarnatakawhere Madhavacharya established temples and monasteries, and in neighboring states, particularly thePandharpurregion.[344]Substantial presence also exists inTripuraandPunjab.[345]

Krishnaism has a limited following outside of India, especially associated with 1960s counter-culture, including a number of celebrity followers, such asGeorge Harrison,due to its promulgation throughout the world by the founder-acharya of theInternational Society for Krishna Consciousness(ISKCON)A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.[346][347][348]

Academic study

Vaishnava theology has been a subject of study and debate for many devotees, philosophers and scholars within India for centuries. Vaishnavism has its own academic wing inUniversity of Madras- Department of Vaishnavism.[349]In recent decades this study has also been pursued in a number of academic institutions in Europe, such as theOxford Centre for Hindu Studies,Bhaktivedanta College,and Syanandura Vaishnava Sabha, a moderate and progressive Vaishnava body headed by Gautham Padmanabhan in Trivandrum which intends to bring about a single and precise book calledHari-granthato include all Vaishnava philosophies.

Hymns

Mantras

Hails

See also

- Hindu denominations

- Divya Prabhandham

- Nanaghat Inscription– a 1st-century BCE Vaishnava inscription

- Vasu Doorjamb Inscription– a 1st-century CE inscription from Vaishnava temple

Explanatory notes

- ^Dandekar 1987,p. 9499: "The origin of Vaiṣṇavism as a theistic sect can by no means be traced back to the Ṛgvedic god Viṣṇu. In fact, Vaiṣṇavism is in no sense Vedic in origin. (...) Strangely, the available evidence shows that the worship of Vāsudeva, and not that of Viṣṇu, marks the beginning of what we today understand by Vaiṣṇavism. This Vāsudevism, which represents the earliest known phase of Vaiṣṇavism, must already have become stabilized in the days of Pāṇini (Seventh to fifth centuries bce)."

- ^abKlostermaier: "Present day Krishna worship is an amalgam of various elements. According to historical testimoniesKrishna-Vasudevaworship already flourished in and aroundMathuraseveral centuries before Christ. Next came the sect of Krishna Govinda. Later the worship of Bala-Krishna, the Divine Child Krishna was added — a quite prominent feature of modern Krishnaism. The last element seems to have been Krishna Gopijanavallabha, Krishna the lover of the Gopis, among whomRadhaoccupies a special position. In some books Krishna is presented as the founder and first teacher of the Bhagavata religion. "[35]

- ^Friedhelm Hardy in his "Viraha-bhakti" analyses the history of Krishnaism, specifically all pre-11th-century sources starting with the stories of Krishna and thegopi,andMayonmysticism of the VaishnavaTamilsaints, SangamTamil literatureandAlvars' Krishna-centred devotion in therasaof the emotional union and the dating and history of theBhagavata Purana.[48][49]

- ^Klostermaier: "Bhagavad Gitaand theBhagavata Purana,certainly the most popular religious books in the whole of India. Not only was Krsnaism influenced by the identification of Krsna with Vishnu, but also Vaishnavism as a whole was partly transformed and reinvented in the light of the popular and powerful Krishna religion. Bhagavatism may have brought an element of cosmic religion into Krishna worship; Krishna has certainly brought a strongly human element into Bhagavatism [...] The center of Krishna-worship has been for a long timeBrajbhumi,the district ofMathurathat embraces also Vrindavana, Govardhana, and Gokula, associated with Krishna from time immemorial. Many millions of Krishnabhaktasvisit these places ever year and participate in the numerous festivals that reenact scenes from Krshna's life on Earth. "[35]

- ^(a)Steven Rosen and William Deadwyler III: "the word sampradaya literally means 'a community'."[231]

(b)Federico Squarcini traces the semantic history of the wordsampradaya,calling it a tradition, and adds, "Besides its employment in the ancient Buddhist literature, the term sampradaya circulated widely in Brahamanic circles, as it became the most common word designating a specific religious tradition or denomination".[232] - ^Based on a list of gurus found in Baladeva Vidyabhusana'sGovinda-bhasyaandPrameya-ratnavali,ISKCON situates Gaudiya Vaishnavism within the Brahma sampradaya, calling itBrahma-Madhva-Gaudiya Vaisnava Sampradaya.[231]

- ^Stephen Knapp: "Actually there is some confusion about him, as it seems there have been three Vishnu Svamis: Adi Vishnu Svami (around the 3rd century BCE, who introduced the traditional 108 categories of sannyasa), Raja Gopala Vishnu Svami (8th or 9th century CE), and Andhra Vishnu Svami (14th century)."[239]

- ^Gavin Flood notes that Jñāneśvar is sometimes regarded as the founder of the Warkari sect, but that Vithoba-worship predates him.[240]

- ^Hiltebeitel: "Practically, Adi Shankara Acharya fostered a rapprochement between Advaita andsmartaorthodoxy, which by his time had not only continued to defend thevarnasramadharmatheory as defining the path ofkarman,but had developed the practice ofpancayatanapuja( "five-shrine worship" ) as a solution to varied and conflicting devotional practices. Thus one could worship any one of five deities (Vishnu, Siva, Durga, Surya, Ganesa) as one'sistadevata( "deity of choice" ). "[252]

- ^Vishnu is regionally called by other names, such as Ranganatha at Srirangam temple in Tamil Nadu.[265]

- ^Zelliot & Berntsen 1988,p. xviii: "Varkari cult is rural and non-Brahman in character.",Sand 1990,p. 34: "the more or less anti-ritualistic and anti-brahmanical attitudes of Warkari sampradaya."

- ^Website Adherents gives numbers as of year 1999.[337]

- ^According to Jones and Ryan, "The followers of Vaishnavism are many fewer than those of Shaivism, numbering perhaps 200 million."[120]}[dubious–discuss]

Citations

- ^abcdefDandekar 1987.

- ^Pratapaditya Pal (1986).Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 BCE–700 CE.University of California Press. pp. 24–25.ISBN978-0-520-05991-7.

- ^Stephan Schuhmacher (1994).The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion: Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Zen.Shambhala. p. 397.ISBN978-0-87773-980-7.

- ^abcdeHardy 1987.

- ^abFlood 1996,p. 117.

- ^abcJohnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013).The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography.John Wiley & Sons. p. 400.ISBN978-1-118-32303-8.

- ^"Chapter 1 Global Religious Populations"(PDF).January 2012. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 October 2013.

- ^abcdefghijkDandekar 1987,p. 9499.

- ^abcd"Vaishnava".philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 12 February 2012.Retrieved22 May2008.

- ^abFlood 1996,p. 120.

- ^Flood 1996,p. 119,120-121.

- ^Eliade, Mircea; Adams, Charles J. (1987).The Encyclopedia of religion.Macmillan. p.168.ISBN978-0-02-909880-6.

- ^abGonda 1993,p. 163.

- ^abKlostermaier 2007,pp. 206–217, 251–252.

- ^Matchett 2001,pp. 3–9.

- ^abAnna King 2005,pp. 32–33.

- ^abMukherjee 1981;Eschmann, Kulke & Tripathi 1978;Hardy 1987,pp. 387–392;Patnaik 2005;Miśra 2005,chapter 9. Jagannāthism;Patra 2011.

- ^Hawley 2015,pp. 10–12, 33–34.

- ^Lochtefeld 2002b,pp. 731–733.

- ^abBeck 2005a,pp. 76–77.

- ^abFowler 2002,pp. 288–304, 340–350.

- ^Raj & Harman 2007,pp. 165–166.

- ^Lochtefeld 2002b,pp. 553–554.

- ^abcFlood 1996,pp. 121–122.

- ^abcSchrader 1973,pp. 2–21.

- ^abKlostermaier 2007,pp. 46–52, 76–77.

- ^Singh, Upinder (2008).A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century.Pearson Education India. pp. 436–438.ISBN978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^Osmund Bopearachchi,Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence,2016.

- ^Srinivasan, Doris (1997).Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art.BRILL. p. 215.ISBN978-90-04-10758-8.

- ^F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995).The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States.Cambridge University Press. pp. 303–304.ISBN978-0-521-37695-2.

- ^Radhakumud Mookerji (1959).The Gupta Empire.Motilal Banarsidass. p. 3.ISBN978-81-208-0440-1.

- ^Preciado-Solís 1984,p. 1–16.

- ^Dandekar 1987,p. 9498.

- ^Ramkrishna Gopal Bhandarkar;Ramchandra Narayan Dandekar (1976).Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar as an Indologist: A Symposium.India: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 38–40.

- ^abcdefKlostermaier 2007.

- ^Dalal 2010,pp. 54–55.

- ^Dandekar 1971,p. 270.

- ^abcdefghDandekar 1987,p. 9500.

- ^William K. Mahony (1998).The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination.New York: SUNY Press. pp. 13–14.ISBN978-0-7914-3579-3.

- ^abcWelbon 1987a.

- ^abWelbon 1987b.

- ^Aiyangar 2019,p. 16.

- ^Aiyangar 2019,pp. 93–94.

- ^Aiyangar 2019,p. 95.

- ^Thapar, Romila (28 June 1990).A History of India.Penguin UK.ISBN978-0-14-194976-5.

- ^Inden, Ronald B. (2000).Imagining India.C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 249.ISBN978-1-85065-520-6.

- ^Chari, S. M. Srinivasa (1997).Philosophy and Theistic Mysticism of the Āl̲vārs.Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 244.ISBN978-81-208-1342-7.

- ^abcHardy, Friedhelm (2001).Viraha-Bhakti: The Early History of Krsna Devotion in South India (Oxford University South Asian Studies Series).Oxford University Press, USA.ISBN978-0-19-564916-1.

- ^"Book review - FRIEDHELM HARDY, Viraha Bhakti: The Early History of Krishna Devotion in South India. Oxford University Press, Nagaswamy 23 (4): 443 – Indian Economic & Social History Review".ier.sagepub.Retrieved29 July2008.

- ^abMonius 2005,pp. 139–149.

- ^Norman Cutler (1987)Songs of Experience: The Poetics of Tamil Devotion,p. 13

- ^ab"Devotion to Mal (Mayon)".philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 12 February 2012.Retrieved22 May2008.

- ^Singh, Upinder (2008).A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century.Pearson Education India. p. 617.ISBN978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^Aiyangar 2019,pp. 77–78.

- ^GANGASHETTY, RAMESH (30 October 2019).THIRTHA YATRA: A GUIDE TO HOLY TEMPLES AND THIRTHA KSHETRAS IN INDIA.Notion Press.ISBN978-1-68466-134-3.

- ^For English summary, see p. 80Schmid, Charlotte (1997)."Les Vaikuṇṭha gupta de Mathura: Viṣṇu ou Kṛṣṇa?".Arts Asiatiques.52:60–88.doi:10.3406/arasi.1997.1401.

- ^Ganguli 1988,p. 36.

- ^abcBakker, Hans T. (12 March 2020).The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia.Barkhuis. pp. 98–99, 93.ISBN978-94-93194-00-7.

- ^Ramnarace 2014,p. 180.

- ^S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1988).Tattva-muktā-kalāpa.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–5.ISBN978-81-208-0266-7.

- ^Klaus K. Klostermaier (1984).Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India.Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 101–103.ISBN978-0-88920-158-3.

- ^Annangaracariyar 1971.

- ^Seth 1962.

- ^Smith 1976,pp. 143–156.

- ^Gupta & Valpey 2013,pp. 2–10.

- ^Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H., eds. (1987).The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–5.ISBN978-81-208-0277-3.

- ^C. J. Bartley (2013).The Theology of Ramanuja: Realism and Religion.Routledge. pp. 1–4, 52–53, 79.ISBN978-1-136-85306-7.

- ^abBeck 2005,p. 6.

- ^Jackson 1992.

- ^Jackson 1991.

- ^John Stratton Hawley (2015), A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, Harvard University Press,ISBN978-0-674-18746-7,pp. 304–310

- ^abcdeC. J. Bartley (2013).The Theology of Ramanuja: Realism and Religion.Routledge. pp. 1–4.ISBN978-1-136-85306-7.

- ^Delmonico, Neal (4 April 2004)."Caitanya Vais.n. avism and the Holy Names"(PDF).Bhajan Kutir.Retrieved29 May2017.

- ^Carney 2020;Jones & Ryan 2007,pp. 79–80, Bharati, Baba Premanand.

- ^Selengut, Charles (1996)."Charisma and Religious Innovation:Prabhupada and the Founding of ISKCON".ISKCON Communications Journal.4(2). Archived fromthe originalon 13 July 2011.

- ^Herzig, T.; Valpey, K (2004)."Re—visioning Iskcon".The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant.Columbia University Press.ISBN978-0-231-12256-6.Retrieved10 January2008.

- ^Prabhupada - He Built a House,Satsvarupa dasa Goswami,Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1983,ISBN0-89213-133-0p. xv

- ^Schweig 2013,p. 18.