Organ (biology)

| Organ | |

|---|---|

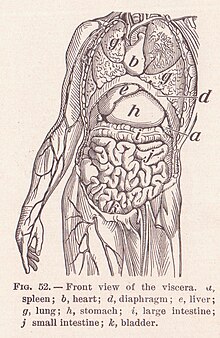

Many of the internal organs of thehuman body | |

| Details | |

| System | Organ systems |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | organum |

| Greek | oργανο |

| FMA | 67498 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In a multicellularorganism,anorganis a collection oftissuesjoined in a structural unit to serve a common function.[1]In thehierarchy of life,an organ lies betweentissueand anorgan system.Tissues are formed from same typecellsto act together in a function. Tissues of different types combine to form an organ which has a specific function. Theintestinal wallfor example is formed byepithelial tissueandsmooth muscle tissue.[2]Two or more organs working together in the execution of a specific body function form an organ system, also called abiological systemor body system.

An organ's tissues can be broadly categorized asparenchyma,the functional tissue, andstroma,the structural tissue with supportive, connective, orancillaryfunctions. For example, thegland's tissue that makes thehormonesis theparenchyma,whereas the stroma includes thenervesthat innervate the parenchyma, theblood vesselsthat oxygenate and nourish it and carry away itsmetabolicwastes, and theconnective tissuesthat provide a suitable place for it to be situated and anchored. The main tissues that make up an organ tend to have commonembryologicorigins, such as arising from the samegerm layer.Organs exist in most multicellularorganisms.Insingle-celled organismssuch as members of theeukaryotes,thefunctional analogueof an organ is known as anorganelle.In plants, there are three main organs.[3]

The number of organs in any organism depends on the definition used. By one widely adopted definition, 79 organs have been identified in the human body.[4]

Animals[edit]

Except forplacozoans,multicellularanimalsincluding humans have a variety oforgan systems.These specific systems are widely studied inhuman anatomy.The functions of these organ systems often share significant overlap. For instance, thenervousandendocrine systemboth operate via a shared organ, thehypothalamus.For this reason, the two systems are combined and studied as theneuroendocrine system.The same is true for themusculoskeletal systembecause of the relationship between themuscularandskeletal systems.

- Cardiovascular system:pumping and channelingbloodto and from thebodyandlungswithheart,bloodandblood vessels.

- Digestive system:digestionand processing food withsalivary glands,esophagus,stomach,liver,gallbladder,pancreas,intestines,colon,mesentery,rectumandanus.

- Endocrine system:communication within the body usinghormonesmade byendocrine glandssuch as thehypothalamus,pituitarygland,pineal bodyor pineal gland,thyroid,parathyroidsandadrenals,i.e., adrenal glands.

- Excretory system:kidneys,ureters,bladderandurethrainvolved in fluid balance,electrolytebalance and excretion ofurine.

- Lymphatic system:structures involved in the transfer oflymphbetweentissuesand theblood stream,the lymph and thenodesandvesselsthat transport it including theimmune system:defending againstdisease-causing agents withleukocytes,tonsils,adenoids,thymusandspleen.

- Integumentary system:skin,hairandnailsof mammals. Alsoscalesoffish,reptiles,andbirds,andfeathersof birds.

- Muscular system:movement withmuscles.

- Nervous system:collecting, transferring and processing information withbrain,spinal cordandnerves.

- Reproductive system:thesex organs,such asovaries,oviducts,uterus,vulva,vagina,testicles,vas deferens,seminal vesicles,prostateandpenis.

- Respiratory system:the organs used forbreathing,thepharynx,larynx,trachea,bronchi,lungsanddiaphragm.

- Skeletal system:structural support and protection withbones,cartilage,ligamentsandtendons.

Viscera[edit]

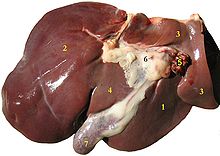

In the study ofanatomy,viscera(sg.:viscus) refers to theinternal organsof theabdominal,thoracic,andpelvic cavities.[5]The abdominal organs may be classified assolid organsorhollow organs.The solid organs are theliver,pancreas,spleen,kidneys,andadrenal glands.The hollow organs of the abdomen are thestomach,intestines,gallbladder,bladder,andrectum.[6]In thethoracic cavity,theheartis a hollow, muscular organ.[7]Splanchnologyis the study of the viscera.[8]The term "visceral" is contrasted with the term "parietal",meaning" of or relating to the wall of a body part,organ or cavity".[9]The two terms are often used in describing a membrane or piece of connective tissue, referring to the opposing sides.[10]

Origin and evolution[edit]

The organ level of organisation inanimalscan be first detected inflatwormsand the more derivedphyla,i.e. thebilaterians.The less-advancedtaxa(i.e.Placozoa,Porifera,CtenophoraandCnidaria) do not show consolidation of their tissues into organs.

More complex animals are composed of different organs, which have evolved over time. For example, the liver and heart evolved in thechordatesabout 550-500 million years ago, while the gut and brain are even more ancient, arising in the ancestor of vertebrates, insects, molluscs, and worms about 700-650 million years ago.

Given the ancient origin of most vertebrate organs, researchers have looked for model systems, where organs have evolved more recently, and ideally have evolved multiple times independently. An outstanding model for this kind of research is theplacenta,which has evolved more than 100 times independently in vertebrates, has evolved relatively recently in some lineages, and exists in intermediate forms in extant taxa.[11]Studies on the evolution of the placenta have identified a variety of genetic and physiological processes that contribute to the origin and evolution of organs, these include the re-purposing of existing animal tissues, the acquisition of new functional properties by these tissues, and novel interactions of distinct tissue types.[11]

Plants[edit]

The study of plant organs is covered inplant morphology.Organs ofplantscan be divided into vegetative and reproductive. Vegetative plant organs includeroots,stems,andleaves.The reproductive organs are variable. Inflowering plants,they are represented by theflower,seedandfruit.[citation needed]Inconifers,the organ that bears the reproductive structures is called acone.In other divisions (phyla) of plants, the reproductive organs are calledstrobili,inLycopodiophyta,or simply gametophores inmosses.Common organ system designations in plants include the differentiation of shoot and root. All parts of the plant above ground (in non-epiphytes), including the functionally distinct leaf and flower organs, may be classified together as the shoot organ system.[12]

The vegetative organs are essential for maintaining the life of a plant. While there can be 11 organ systems in animals, there are far fewer in plants, where some perform the vital functions, such asphotosynthesis,while the reproductive organs are essential inreproduction.However, if there isasexualvegetative reproduction,the vegetative organs are those that create the new generation of plants (seeclonal colony).

Society and culture[edit]

Many societies have a system fororgan donation,in which a living or deceased donor's organ aretransplantedinto a person with a failing organ. The transplantation of larger solid organs often requiresimmunosuppressionto preventorgan rejectionorgraft-versus-host disease.

There is considerable interest throughout the world in creatinglaboratory-grownorartificial organs.[citation needed]

Organ transplants[edit]

Beginning in the 20th century[13]organ transplantsbegan to take place as scientists knew more about the anatomy of organs. These came later in time as procedures were often dangerous and difficult.[14]Both the source and method of obtaining the organ to transplant are major ethical issues to consider, and because organs as resources for transplant are always more limited than demand for them, various notions of justice, includingdistributive justice,are developed in the ethical analysis. This situation continues as long as transplantation relies upon organ donors rather than technological innovation, testing, and industrial manufacturing.[citation needed]

History[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(February 2018) |

The English word "organ" dates back to the twelfth century and refers to any musical instrument. By the late 14th century, the musical term's meaning had narrowed to refer specifically to thekeyboard-based instrument.At the same time, a second meaning arose, in reference to a "body part adapted to a certain function".[15]

Plant organs are made from tissue composed of different types of tissue. The three tissue types are ground, vascular, and dermal.[16]When three or more organs are present, it is called an organ system.[17]

The adjectivevisceral,alsosplanchnic,is used for anything pertaining to the internal organs. Historically, viscera of animals were examined byRomanpaganpriestslike theharuspicesor theaugursin order to divine the future by their shape, dimensions or other factors.[18]This practice remains an important ritual in some remote, tribal societies.

The term "visceral" is contrasted with the term "parietal",meaning" of or relating to the wall of a body part,organ or cavity"[9]The two terms are often used in describing a membrane or piece of connective tissue, referring to the opposing sides.[19]

Antiquity[edit]

Aristotleused the word frequently in his philosophy, both to describe the organs of plants or animals (e.g. the roots of a tree, the heart or liver of an animal), and to describe more abstract "parts" of an interconnected whole (e.g. his logical works, taken as a whole, are referred to as theOrganon).[20]

Some alchemists (e.g.Paracelsus) adopted theHermetic Qabalahassignment between the seven vital organs and the sevenclassical planetsas follows: [21]

| Planet | Organ |

|---|---|

| Sun | Heart |

| Moon | Brain |

| Mercury | Lungs |

| Venus | Kidneys |

| Mars | Gall bladder |

| Jupiter | Liver |

| Saturn | Spleen |

Chinese traditional medicinerecognizes eleven organs, associated with thefive Chinese traditional elementsand withyin and yang,as follows:

| Element | Yin/yang | Organ |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | yin | liver |

| yang | gall bladder | |

| Fire | yin | heart |

| yang | small intestine /san jiao | |

| Earth | yin | spleen |

| yang | stomach | |

| Metal | yin | lungs |

| yang | large intestine | |

| Water | yin | kidneys |

| yang | bladder |

The Chinese associated the five elements with the five planets (Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Saturn, and Mercury) similar to the way the classical planets were associated with different metals. Theyinandyangdistinction approximates the modern notion of solid and hollow organs.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Widmaier, E P; Raff, H; Strang, KT (2014).Vander's Human Physiology(12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education.ISBN978-0-07-128366-3.[page needed]

- ^Kent, Michael (2000).Advanced biology.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 81.ISBN0199141959.

- ^"Botany/Plant structure – Wikibooks, open books for an open world".en.wikibooks.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-02-07.Retrieved2018-02-06.

- ^"New organ named in digestive system".BBC News.2017.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-03-24.Retrieved2018-02-05.

- ^Bell, Daniel J."Viscera | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org".Radiopaedia.

- ^Bell, Daniel J."Solid and hollow abdominal viscera | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org".Radiopaedia.Retrieved24 November2021.

- ^"Biology of the Heart – Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders".MSD Manual Consumer Version.Retrieved24 November2021.

- ^"Medical Definition of SPLANCHNOLOGY".Merriam-Webster.Retrieved25 November2021.

- ^ab"Parietal – Learning brain structure, function and variability from neuroimaging data".team.inria.fr.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-02-10.Retrieved2018-02-10.

- ^"Thoracic cavity".Am Boss.Archivedfrom the original on 21 July 2019.Retrieved8 September2019.

- ^abGriffith, Oliver W.; Wagner, Günter P. (23 March 2017). "The placenta as a model for understanding the origin and evolution of vertebrate organs".Nature Ecology & Evolution.1(4): 0072.Bibcode:2017NatEE...1...72G.doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0072.PMID28812655.S2CID32213223.

- ^"The Plant Body | Boundless Biology".courses.lumenlearning.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-01-21.Retrieved2019-03-19.

- ^"Timeline of Historical Events and Significant Milestones".Organ Donor Government Web.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2019.Retrieved19 March2019.

- ^"transplant | Definition, Types, & Rejection".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-03-27.Retrieved2019-03-19.

- ^"organ (n.)".Online Etymology Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2019.Retrieved22 March2019.

- ^"Plant Development I: Tissue differentiation and function".Biology 1520 (Georgia Tech).Georgia Tech.Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2019.Retrieved8 September2019.

- ^"Organ System – Definition and Examples | Biology Dictionary".Biology Dictionary.2016-10-31.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-02-10.Retrieved2018-02-10.

- ^Dickie, Matthew W. (February 23, 2003).Magic and Magicians in the Greco-Roman World(1 ed.). Routledge. p. 274.ISBN0415311292.

- ^"Thoracic cavity".Am Boss.Archivedfrom the original on 21 July 2019.Retrieved8 September2019.

- ^Lennox, James (31 Jan 2017)."Aristotle's Biology".Plato.Stanford University.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2019.Retrieved23 March2019.

Section 2: Aristotle's Philosophy of Science

- ^Ball, Philip (2007).The devil's doctor.London: Arrow.ISBN978-0-09-945787-9.OCLC124919518.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-08-02.Retrieved2021-08-02.

External links[edit]

Media related toOrgans (anatomy)at Wikimedia Commons

Media related toOrgans (anatomy)at Wikimedia Commons