Lancelot-Grail

| Lancelot–Grail | |

|---|---|

| Vulgate Cycle | |

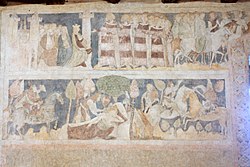

Scenes from theLancelot Properdepicted in a Polish 14th-century fresco atSiedlęcin Tower | |

| Author(s) | Unknown (in part directly based onRobert de BoronandChrétien de Troyes) |

| Ascribed to | Self-attributed toGautier Map |

| Language | Old French |

| Date | c.1210–1235 |

| Genre | Chivalric romance,pseudo-chronicle |

| Subject | Matter of Britain |

TheLancelot-Grail Cycle(a modern title invented byFerdinand Lot[1]), also known as theVulgate Cycle(from the Latineditio vulgata,"common version", a modern title invented by H. Oskar Sommer[2]) or thePseudo-Map Cycle(named so afterWalter Map,itspseudo-author), is an early 13th-century FrenchArthurianliterary cycleconsisting of interconnectedproseepisodes ofchivalric romanceoriginally written inOld French.The work of unknown authorship, presenting itself as a chronicle of actual events, retells the legend ofKing Arthurby focusing on the love affair betweenLancelotandGuinevere,the religious quest for theHoly Grail,and the life ofMerlin.The highly influential cycle expands onRobert de Boron's "Little Grail Cycle" and the works ofChrétien de Troyes,previously unrelated to each other, by supplementing them with additional details and side stories, as well as lengthy continuations, while tying the entire narrative together into a coherent single tale. Its alternate titles include Philippe Walter's 21st-century editionLe Livre du Graal( "The Book of the Grail" ).

There is no unity of place within the narrative, but most of the episodes take place in Arthur's kingdom ofLogres.One of the main characters is Arthur himself, around whom gravitates a host of other heroes, many of whom areKnights of the Round Table.The chief of them is the famed Lancelot, whose chivalric tale is centered around his illicit romance with Arthur's wife, Queen Guinevere. However, the cycle also tells of adventures of a more spiritual type. Most prominently, they involve the Holy Grail, the vessel that contained the blood of Christ, which is searched for by many members of the Round Table until Lancelot's sonGalahadultimately emerges as the winner of this sacred journey. Other major plotlines include the accounts of the life of Merlin and of the rise and fall of Arthur.

After its completion around 1230–1235, theLancelot–Grailwas soon followed by its major reworking known as thePost-Vulgate Cycle.Together, the two prose cycles with their abundance of characters and stories represent a major source of the legend of Arthur as they constituted the most widespread form of Arthurian literature of the late medieval period, during which they were both translated into multiple European languages and rewritten into alternative variants, including having been partially turned into verse. They also inspired various later works of Arthurian romance, eventually contributing the most to the compilationLe Morte d'Arthurthat formed the basis for a modern canon of Arthuriana that is still prevalent today.

Composition and authorship

[edit]

The Vulgate Cycle emphasizes Christian themes in the legend ofKing Arthur,in particular in the story of theHoly Grail.As inRobert de Boron's poemMerlin(c. 1195–1210), the cycle states that its first parts have been derived from theLivre du Graal( "The Book of the Grail" ) that is described as a text dictated byMerlinhimself to his confessorBlaisein the early years of Arthur's reign. Next, following the demise of Merlin, there are more supposed original (fictitious) authors of the later parts of the cycle, the following list using one of their multiple spelling variants: Arodiens de Cologne (Arodian ofCologne), Tantalides de Vergeaus (Tantalides ofVercelli), Thumas de Toulete (Thomas ofToledo), and Sapiens de Baudas (Sapient ofBaghdad).[3]These characters are described as the scribes in service of Arthur who recorded the deeds of theKnights of the Round Table,including the grand Grail Quest, as relayed to them by the eyewitnesses of the events beings told in the story. It is uncertain whether the medieval readers actually believed in the truthfulness of the centuries-old "chronicle" characterisation or if they recognised it as a contemporary work of creative fiction.[4]

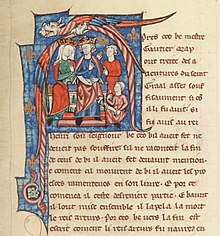

Welsh writerGautier (Walter) Map(c. 1140– c. 1209) is attributed to be the editing author, as can be seen in the notes and illustrations in some manuscripts describing his discovery in an archive atSalisburyof the chronicle ofCamelot,supposedly dating from the times of Arthur, and his translation of these documents fromLatintoOld Frenchas ordered byHenry II of England[5](the location was changed from Salisbury to the mysticalAvalonin a laterWelshredaction[6]). Map's connection has been discounted by modern scholarship, however, as he died too early to be the author and the work is distinctly continental.[7][8][9]

The cycle's actual authorship is unknown, but most scholars today believe it was written by multiple authors. There might have been either a single master-mind planner, the so-called "architect" (as first called so by Jean Frappier, who compared the process to building a cathedral[10]), who may have written the main section (Lancelot Proper), and then overseen the work of multiple other anonymous scribes.[11][12]One theory identified the initiator as French queenEleanor of Aquitaine,who would have set up the project already in 1194.[13][14][15]Alternately, each part may have been composed separately, arranged gradually, and rewritten for consistency and cohesiveness. Regarding the question of the author of theLancelot,Ferdinand Lotsuggested an anonymous clerical court clerk of aristocratic background.[16]

Today it is believed by some (such as editors of theEncyclopædia Britannica[17]) that a group of anonymous French Catholic monks wrote the cycle – or at least theQuestepart (where, according to Fanni Bogdanow, the text's main purpose is to convince sinners to repent[18]), as evident by its veryCistercianspirit ofChristian mysticism(withAugustinianintrusions[19]). Others doubt this, however, and a compromise theory postulates a more secular writer who had spent some time in a Cistercian monastery.[20]Richard Barberdescribed the Cistercian theology of theQuesteas unconventional and complex but subtle, noting its success in appealing to the courtly audience accustomed to more secular romances.[21]

Structure, history and synopsis

[edit]This sectionneeds expansionwith: more detailed synopsis for each branch of the cycle. You can help byadding to it.(August 2023) |

TheLancelot-Grail Cyclemay be divided into three[17]main branches, although more usually into five,[22]with the romancesQuesteandMortregarded as separate from the VulgateLancelot(the latter possibly initially standalone in the original so-called "short version" ).[23]In particular, theLancelot,theQuesteand theMorteare 'so divergent as to leave no doubt that they are the work of different authors'.[24]The story of Lancelot was actually the first to be written (beginningc. 1210–1215).[17][25]The stories of Joseph and Merlin joined the cycle late (beforec. 1235), serving as "prequels" to the main story.[26]

The cycle has a narrative structure close to that of a modern novel in which multiple overlapping events featuring different characters may simultaneously develop in parallel and intertwine with each other through the technique known as interlace (French:entrelacement). Narrative interlacing is most prominent in theQueste,aliterary techniqueused by modern authors such asJ. R. R. Tolkien.

History of the Holy Grail

[edit]

TheVulgateEstoire del Saint Graal(Story of the Holy Grail) is the religious tale of early ChristianJoseph of Arimatheaand how his sonJosephusbrought the Holy Grail to Britain from theHoly Land.Set several centuries prior to the main story, it is derived from Robert de Boron's poemJoseph d'Arimathiewith new characters and episodes added.

History of Merlin

[edit]TheVulgateEstoire de Merlin(Story of Merlin), or just theVulgateMerlin,concerns Merlin's complicated conception and childhood and the early life of Arthur, which Merlin has influence over. It is a redaction of theProseMerlin,itself a conversion of Robert de Boron's poem by the same title. It can be divided into:

- TheVulgateMerlin propre(Merlin Proper), also known asLe Roman de Merlin(The Novel of Merlin), directly based on Robert'sMerlin.

- TheVulgateSuite du Merlin(Continuation of Merlin) /Suite Vulgate du Merlin/Vulgate-Suite,also known asLes Premiers Faits[du roi Arthur][27](The First Acts of King Arthur) or theVulgateMerlin Continuation.Drawing from a variety of other sources, it adds more of Arthur's andGawain's early deeds in which they are being aided by Merlin, in particular in their early wars of internal struggles for power and against foreign enemies (SaxonsandRomans), ending in Arthur's marriage with Guinevere and the restoration of peace, as well as the disappearance of Merlin caused by theLady of the Lake.It is roughly four times longer than the first part.

- A distinctively alternate revision of theSuite du Merlin,found in a single massive yet fragmentary manuscript (BNF fr. 337) dating from after 1230 (contemporary to thePost-Vulgate Cycle) and possibly even the late 13th century,[28]is known asLe Livre d'Artus(The Book of Arthur), as named by H. Oskar Sommer. It was published by Sommer as a supplement to his edition of the Vulgate Cycle, but Carol Dover classified it as actually belonging to the Post-Vulgate Cycle.[29]Conversely, Fanni Bogdanow and Richard Trachsler considered it a text continued from the VulgateMerlinthat would be followed by a hypothetical similarly revised variant of the VulgateLancelot,[30]andHelen Nicholsonwrote about it as a third different sequel to Robert'sMerlinin addition to the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate versions.[31]Contrary to the title given to the work by Sommer, its principal hero is Gawain.[32]It incorporates elements of some Arthurian romances written after the Vulgate Cycle had been completed.[33]

ProseLancelot

[edit]

The cycle's centerpiece partLancelot en prose,also known theEstoire de Lancelot(Story of Lancelot) orLe Livre de Lancelot du Lac(The Life of Lancelot of the Lake), follows the adventures of the eponymous hero as well as many otherKnights of the Round Tableduring the later years of King Arthur's reign up until the appearance of Galahad and the start of the Grail Quest. The separate parts of theLancelot–Queste–Mort Artutrilogy differ greatly in tone, the first (composedc. 1215–1220) can be characterized as colorful, the second (c. 1220–1225) as pious, and the third (c. 1225–1230) as sober:[5][34]

TheVulgateLancelot propre(Lancelot Proper), also known asLe Roman de Lancelot(The Novel of Lancelot) or justLancelot du Lac,is the longest part, making up fully half of the entire cycle.[26]It is inspired by and in part based on Chrétien's poemLancelot, le Chevalier de la Charrette(Lancelot, or the Knight of the Cart).[35]It primarily deals with a series of episodes ofLancelot's early life and with thecourtly lovebetween him and QueenGuinevere,as well as his deep friendship withGalehaut,interlaced with the adventures of Gawain and other knights such asYvain,Hector,Lionel,andBors.TheLancelot Properis regarded as having been written first in the cycle.[16]The actual [Conte de la]Charrette( "[Tale of the] Cart" ), an incorporation of a prose rendition of Chrétien's poem, spans only a small part of the Vulgate text.[36]

Due to its length, modern scholars often divide theLancelotinto various sub-sections, including theEnfances Lancelot( "Lancelot's youth" ) orGalehaut(sometimesGaleaut), further split between theCharretteand its follow-up theSuite de la Charette(Continuation of the Charrette); theAgravain(named after Gawain's brotherAgravain); and thePreparation for the Questlinking the previous ones.[37][38][39][40]It was perhaps originally an independent romance that would begin with Lancelot's birth and finish with a happy ending for him, discovering his true identity and receiving a kiss from Guinevere when he confesses his love for her.[11][41]Elspeth Kennedyidentified the possible non-cyclic ProseLancelotin an early manuscript known as theBNF fr. 768.It is about three times shorter than the later editions and notably the Grail Quest (usually taking place later) is mentioned within the text as already having been completed by Perceval alone.[16][42][43]

Quest for the Holy Grail

[edit]TheVulgateQueste del Saint Graal(Quest for the Holy Grail), also known asLes Aventures ou La Queste del Saint Graal(The Adventures or The Quest for the Holy Grail) or just theVulgateQueste,is, like theEstoire del Saint Graal,another highly religious part of the cycle. It relates how the Grail Quest is undertaken by various knights includingPercevaland Bors, and achieved by Lancelot's sonGalahad,the perfect holy knight who here replaces both Lancelot and Perceval as the chosen hero.[26]Their interlacing adventures are purported to be narrated by Bors, the witness of these events after the deaths of Galahad and Perceval.[44]It is the most innovative part of the cycle as it was not derived from any known earlier stories, including the creation of the character of Galahad as a major new Arthurian hero.

Death of King Arthur

[edit]TheVulgateMort le roi Artu(Death of King Arthur), also known asLa Mort le Roy Artusor just theVulgateMort Artu/La Mort Artu,a tragic account of further wars culminating in the king and his illegitimate sonMordredkilling each other in a near-complete rewrite of the Arthurian chronicle tradition from the works ofGeoffrey of Monmouthand his redactors. It is also connected with the so-called "Mort Artu" epilogue section of theDidotPerceval,a text uncertainly attributed to Robert de Boron, and which itself was based onWace'sRoman de Brut.[45]In a new motif, the ruin of Arthur's kingdom is presented as the disastrous direct consequence of the sin of Lancelot's and Guinevere's adulterous affair.[26]Lancelot eventually dies too, as do the other protagonists who did not die in theQueste,leaving only Bors as a survivor of the Round Table.

Manuscripts

[edit]

As the stories of the cycle were immensely popular in medieval France and neighboring countries between the beginning of the 13th and the beginning of the 16th century, they survived in some two hundred manuscripts in various forms[23][46](not counting printed books since the late 15th century, starting with an edition of theLancelotin 1488). The Lancelot-Graal Project website lists (and links to the scans of many of them) close to 150 manuscripts in French,[47]some fragmentary, others, such asBritish LibraryAdd MS 10292–10294, containing the entire cycle. Besides the British Library, scans of various manuscripts can be seen online through digital library websites of theBibliothèque Nationale de France's Gallica[48](including these from theBibliothèque de l'Arsenal) and theUniversity of Oxford's Digital Bodleian; many illustrations can also be found at the IRHT's Initiale project.[49]The earliest copies are of French origin and date from 1220 to 1230.

Numerous copies were produced in French throughout the remainder of the 13th, 14th and well into the 15th centuries in France, England and Italy, as well as translations into other European languages. Some of the manuscripts are richly illuminated: British Library Royal MS 14 E III, produced in Northern France in the early 14th century and once owned by KingCharles V of France,contains over 100 miniatures with gilding throughout and decorated borders at the beginning of each section.[50]Other manuscripts were made for less wealthy owners and contain very little or no decoration, for example British Library MS Royal 19 B VII, produced in England, also in the early 14th century, with initials in red and blue marking sections in the text and larger decorated initials at chapter-breaks.[51]One notable manuscript is known as theRochefoucauld Grail.

However, very few copies of the entire Lancelot-Grail Cycle survive. Perhaps because it was so vast, copies were made of parts of the legend which may have suited the tastes of certain patrons, with popular combinations containing only the tales of either Merlin or Lancelot.[52][53]For instance, British Library Royal 14 E III contains the sections which deal with the Grail and religious themes, omitting the middle section, which relates Lancelot's chivalric exploits.

Legacy

[edit]Post-Vulgate Cycle

[edit]The Vulgate Cycle was soon afterwards subject to a major revision during the 1230s, in which much was left out and much added. In the resulting far-shorterPost-Vulgate Cycle,also known as theRoman du Graal,Lancelot is no longer the central character. The Post-Vulgate omits almost all of theLancelot Proper,and consequently most of Lancelot and Guinevere's content, instead focusing on the Grail Quest.[26]It also borrows characters and episodes from the first version of theProseTristan(1220), makingTristanone of the main characters.

Other reworkings and influence

[edit]The second version of the ProseTristan(1240) itself partially incorporated the Vulgate Cycle by copying parts of it.[35][54]Along with the ProseTristan,both the Post-Vulgate and the Vulgate original were among the most important sources forThomas Malory's seminal English compilation of Arthurian legend,Le Morte d'Arthur(1470),[26]which has become a template for many modern works.

The 14th-century English poemStanzaicMorte Arthuris a compressed verse translation of the VulgateMort Artu.In the 15th-century Scotland, the first part of the VulgateLancelotwas turned into verse inLancelot of the Laik,a romance love poem with political messages.[55]In the 15th-century England,Henry Lovelich's poemMerlinand the verse romanceOf Arthour and of Merlinwere based on the VulgateMerlinand theMerlin Continuation.

Outside Britain, the VulgateMerlinwas retold in Germany byAlbrecht von Scharfenbergin his lostDer Theure Mörlin,preserved over 100 years later in the "Mörlin" part ofUlrich Fuetrer'sBuch von Abenteuer(1471).Jacob van Maerlant's Dutch translation of theMerlinadded some original content in hisMerlijns Boekalso known asHistorie von Merlijn(1261), as did the Italian writer Paolino Pieri in theStoria di Merlino(1320). The DutchLancelot Compilation(1320) added an original romance to a translation of the ProseLancelot.The ItalianVita de Merlino con le suo Prophetiealso known as theHistoria di Merlino(1379) was loosely adapted from the VulgateMerlin.

The cycle's elements and characters have been also incorporated into various other works in France, such asLes Prophecies de Mérlin(or theProphéties de Merlin) andPalamedes,and elsewhere. Some episodes from the Vulgate Cycle have been adapted into the Third and Fourth Continuations of Chrétien's unfinishedPerceval, the Story of the Grail.[56]Other legacy can be found in the many so-called "pseudo-Arthurian" works in Spain and Portugal.[57]

Modern editions and translations

[edit]Oskar Sommer

[edit]H. Oskar Sommer published the entire original French text of the Vulgate Cycle in seven volumes in the years 1908–1916. Sommer's has been the only complete cycle published as of 2004.[58]The base text used was the British Library Add MS 10292–10294. It is however not a critical edition, but a composite text, where variant readings from alternate manuscripts are unreliably demarcated using square brackets.

- Sommer, H. Oskar. (ed.).The Vulgate Version of the Arthurian Romances

- Volume 1 of 8 (1909):Lestoire del Saint Graal.

- Volume 2 of 8 (1908):Lestoire de Merlin.

- Volume 3 of 8 (1910):Le livre de Lancelot del Lac,Part I.

- Volume 4 of 8 (1911):Le livre de Lancelot del Lac,Part II.

- Volume 5 of 8 (1912):Le livre de Lancelot del Lac,Part III.

- Volume 6 of 8 (1913):Les aventures ou la queste del Saint Graal,La mort le roi Artus.

- Volume 7 of 8 (1913): Supplement:Le livre d'Artus,with glossary

- Volume 8 of 8 (1916): Index of names and places to volumes I-VII

Norris J. Lacy

[edit]The first full English translations of the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate cycles were overseen byNorris J. Lacy.

- Lacy, Norris J. (ed.).Lancelot–Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation.New York: Garland.

- Five-volume set.ISBN0-8240-0700-X.

- Volume 1 of 5 (1 December 1992).ISBN0-8240-7733-4:The History of the Holy GrailandThe Story of Merlin.

- Volume 2 of 5 (1 August 1993).ISBN0-8153-0746-2:Lancelot,Parts I, II and III

- Volume 3 of 5 (1 March 1995).ISBN0-8153-0747-0:Lancelot,Parts IV, V, VI.

- Volume 4 of 5 (1 April 1995).ISBN0-8153-0748-9:The Quest for the Holy Grail,The Death of Arthur,and The Post-Vulgate, Part I: TheMerlin Continuation

- Volume 5 of 5 (1 May 1996).ISBN0-8153-0757-8:The Post-Vulgate, Parts I-III: TheMerlin Continuation(end),The Quest for the Holy Grail,The Death of Arthur,Chapter Summaries and Index of Proper Names

- Lacy, Norris J. (ed.).The Lancelot-Grail Reader: Selections from the Medieval French Arthurian Cycle(2000). New York: Garland.ISBN0-8153-3419-2

- Lacy, Norris J. (ed.).Lancelot–Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation.Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.

- Ten-volume set (March 2010).ISBN9780859917704.

- Volume 1 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842248:The History of the Holy Grail.

- Volume 2 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842347:The Story of Merlin.

- Volume 3 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842262:Lancelot,Parts I and II.

- Volume 4 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842354:Lancelot,Parts III and IV.

- Volume 5 of 10 (October 2010).ISBN9781843842361:Lancelot,Parts V and VI.

- Volume 6 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842378:The Quest for the Holy Grail.

- Volume 7 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842309:The Death of Arthur.

- Volume 8 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842385:The Post-Vulgate Cycle: TheMerlin Continuation.

- Volume 9 of 10 (October 2010).ISBN9781843842330:The Post-Vulgate Cycle:The Quest for the Holy GrailandThe Death of Arthur.

- Volume 10 of 10 (March 2010).ISBN9781843842521:Chapter Summaries for the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate Cycles and Index of Proper Names.

- Lacy, Norris J. (ed.).Lancelot–Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation.Routledge Revivals. Routledge.

- Five-volume set (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87727-5.

- Volume 1 of 5 (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87722-0.

- Volume 2 of 5 (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87723-7.

- Volume 3 of 5 (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87724-4

- Volume 4 of 5 (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87725-1.

- Volume 5 of 5 (April 19, 2010).ISBN978-0-415-87726-8.

Daniel Poirion

[edit]A modern French translation of the Vulgate Cycle in three volumes:

- Poirion, Daniel. (ed.)Le Livre du Graal,Paris: Gallimard[59]

- Volume 1 of 3 (2001):ISBN978-2-07-011342-2:Joseph d'Arimathie,Merlin,Les Premiers Faits du roi Arthur.

- Volume 2 of 3 (2003):ISBN978-2-07-011344-6:Lancelot De La Marche de Gaule à La Première Partie de la quête de Lancelot.

- Volume 3 of 3 (2009):ISBN978-2-07-011343-9:Lancelot: La Seconde Partie de la quête de Lancelot,La Quête du saint Graal,La Mort du roi Arthur.

Other

[edit]- Penguin Classicspublished a translation into English by Pauline Matarasso of theQuesteasThe Quest of the Holy Grailin 1969.[60]It was followed in 1971 with a translation by James Cable of theMort ArtuasThe Death of King Arthur.[61]

- Brepolspublished the original Old French text of theMort Artu(ISBN978-2-503-51676-9) in 2008 and theQueste(ISBN978-2-503-51678-3) in 2012, both based on MS Yale 229 and edited by Elizabeth M. Willingham with annotations in English, under the seriesThe Illustrated Prose Lancelot.

- Judith Shoaf's modern English translation of the VulgateQuestewas published byBroadview PressasThe Quest for the Holy Grailin 2018 (ISBN978-1-55481-376-6). It contains many footnotes explaining its connections with other works of Arthurian literature.[62]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^The History of the Holy Grail.Boydell & Brewer Ltd. 2010.ISBN978-1-84384-224-8.

- ^Korrel, Peter (January 1984).An Arthurian Triangle: A Study of the Origin, Development, and Characterization of Arthur, Guinevere, and Modred.Brill Archive.ISBN9004072721.

- ^Coleman, Joyce (2020)."The Matter of Pseudo-History: Textuality, Aurality, and Visuality in the Arthurian Vulgate Cycle".Mediaevalia.41:71–101.doi:10.1353/mdi.2020.0003.S2CID226438977.

- ^Brandsma 2010.

- ^abSmith, Joshua Byron (2017).Walter Map and the Matter of Britain.University of Pennsylvania Press.ISBN9780812294163.

- ^Carley, James P.; Carley, James Patrick (2001).Glastonbury Abbey and the Arthurian Tradition.Boydell & Brewer.ISBN9780859915724.

- ^Brandsma 2010,p. 200.

- ^Lacy 2010,p. 21–22.

- ^Loomis, Roger Sherman (1991).The Grail: From Celtic Myth to Christian Symbol.Princeton University Press.ISBN9780691020754.

- ^Brandsma, Frank. "LANCELOT PART 3."Arthurian Literature XIX: Comedy in Arthurian Literature,vol. 19, Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY, 2003, pp. 117–134. JSTOR. Accessed 1 Aug. 2020.

- ^abLacy, Norris J. (2005).The Fortunes of King Arthur.DS Brewer.ISBN9781843840619.

- ^Lie 1987,p. 13-14.

- ^Matarasso, Pauline Maud (1979).The Redemption of Chivalry: A Study of the Queste Del Saint Graal.Librairie Droz.ISBN9782600035699.

- ^Lie 1987.

- ^Carman, J. Neale (1973).A Study of the Pseudo-Map Cycle of Arthurian Romance.The University Press of Kansas.SBN7006-0100-7.

- ^abcDover 2003,p. 87.

- ^abc"Vulgate cycle | medieval literature".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved10 December2018.

- ^Norris, Ralph (2009). "Sir Thomas Malory and" The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnell "Reconsidered".Arthuriana.19(2): 82–102.doi:10.1353/art.0.0051.JSTOR27870964.S2CID162024940.

- ^Frese, Dolores Warwick (2008)."Augustinian Intrusions in the" Queste del Saint Graal ": Converting 'Pagan Gold' to Christian Currency".Arthuriana.18(1): 3–21.doi:10.1353/art.2008.0001.JSTOR27870892.

- ^Karen Pratt,The Cistercians and the Queste del Saint GraalArchived31 August 2020 at theWayback Machine.King's College, London.

- ^Barber, Richard (2003). "Chivalry, Cistercianism and the Grail".A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle.Boydell & Brewer. pp. 3–12.ISBN9780859917834.JSTOR10.7722/j.ctt9qdj80.7.

- ^Lupack, Alan (2005).The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-280287-3.

- ^ab"The Story: Outline of the Lancelot-Grail Romance".lancelot-project.pitt.edu.Retrieved9 June2019.

- ^Cable, James (1971).The Death of King Arthur.Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-14-044255-7.

- ^"Lancelot-Grail Cycle - Medieval Studies - Oxford Bibliographies - obo".oxfordbibliographies.Retrieved9 June2019.

- ^abcdefLacy 2010,p. 6.

- ^Sunderland 2010,p. 63.

- ^Bruce, James Douglas (1974).The Evolution of Arthurian Romance from the Beginnings Down to the Year 1300.Slatkine Reprints.

- ^Dover 2003,p. 16.

- ^The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature.University of Wales Press. 15 October 2020.ISBN9781786837431– via Google Books.

- ^Nicholson, Helen (22 April 2001).Love, War, and the Grail.BRILL.ISBN9004120149– via Google Books.

- ^Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; Ihle, Sandra Ness; Kalinke, Marianne E.; Thompson, Raymond H. (5 September 2013).The New Arthurian Encyclopedia: New edition.Routledge.ISBN9781136606335– via Google Books.

- ^Busby, Keith (8 June 2022).Codex and Context: Reading Old French Verse Narrative in Manuscript, Volume II.BRILL.ISBN9789004485983– via Google Books.

- ^Lacy 2010,p. 8.

- ^ab"What is the Lancelot-Grail?".lancelot-project.pitt.edu.Retrieved9 June2019.

- ^Weigand, Hermann J. (1956).Three Chapters on Courtly Love in Arthurian France and Germany.Vol. 17. University of North Carolina Press.doi:10.5149/9781469658629_weigand.ISBN9781469658629.JSTOR10.5149/9781469658629_weigand.

- ^Lie 1987,p. 14.

- ^Brandsma 2010,p. 11.

- ^Lacy, Norris J.; Kelly, Douglas; Busby, Keith (1987).The Legacy of Chrétien de Troyes: Chrétien et ses contemporains.Rodopi.ISBN9789062037384.

- ^Chase & Norris, p. 26-27.

- ^Brandsma 2010,p. 15.

- ^Sunderland 2010,p. 98.

- ^Brandsma 2010,p. 4.

- ^Archibald, Elizabeth; Johnson, David F. (2008).Arthurian Literature XXV.Boydell & Brewer Ltd.ISBN9781843841715.

- ^The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature.University of Wales Press. 15 October 2020.ISBN9781786837431– via Google Books.

- ^Dover 2003,p. 219.

- ^"Lancelot-Grail Manuscripts- Chronology and Geographical Distribution".lancelot-project.pitt.edu.Retrieved9 June2019.

- ^"BnF - La légende du roi Arthur: Manuscrits numérisées".expositions.bnf.fr(in French).Retrieved12 June2019.

- ^"Initiale".initiale.irht.cnrs.fr.Retrieved12 June2019.

- ^"Digitised Manuscripts".bl.uk.

- ^Wight, C."Details of an item from the British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts".bl.uk.

- ^Sunderland 2010,p. 99.

- ^Lacy 2010,p. 14.

- ^Sunderland 2010,p. 6.

- ^"Lancelot of the Laik: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects".d.lib.rochester.edu.

- ^Gaggero, Massimiliano (2013). "Verse and Prose in the Continuations of Chrétien de Troyes'" Conte du Graal "".Arthuriana.23(3): 3–25.doi:10.1353/art.2013.0027.JSTOR43855455.S2CID161312740.

- ^Michael Harney's "SpanishLancelot-GrailHeritage "inA Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle.

- ^Burns, E. Jane (1995),"Vulgate Cycle",in Kibler, William W. (ed.),Medieval France: An Encyclopedia,Garland, pp. 1829–1831,ISBN9780824044442

- ^Poirion, Daniel (2001).Le Livre du Graal.Paris: Gallimard.ISBN978-2-07-011342-2.

- ^"The Quest of the Holy Grail by Anonymous | PenguinRandomHouse: Books".PenguinRandomhouse.Retrieved9 June2019.

- ^The Death of King Arthur.Translated by Cable, James. Penguin Random House UK. 30 January 1975 [1971].ISBN978-0-141-90778-9.

- ^McCullough, Ann (12 August 2019)."The Quest of the Holy Grail ed. by Judith Shoaf (review)".Arthuriana.29(4): 85–86.doi:10.1353/art.2019.0048.S2CID212815856– via Project MUSE.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brandsma, Frank (2010).The Interlace Structure of the Third Part of the Prose Lancelot.Boydell & Brewer.ISBN9781843842576.

- Lacy, Norris J., ed. (2010).The History of the Holy Grail.Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. Vol. 1. Translated by Chase, Carol J. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer.ISBN9781843842248.

- Dover, Carol (2003).A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle.DS Brewer.ISBN9780859917834.

- Lie, Orlanda S. H. (1987).The Middle Dutch Prose Lancelot: A Study of the Rotterdam Fragments and Their Place in the French, German, and Dutch Lancelot en Prose Tradition.Uitgeverij Verloren.ISBN9780444856470.

- Sunderland, Luke (2010).Old French Narrative Cycles: Heroism Between Ethics and Morality.Boydell & Brewer.ISBN9781843842200.

External links

[edit]- The Lancelot-Grail Project by the University of Pittsburgh

- British Library Virtual Exhibition of Arthurian Manuscripts: The Prose Lancelot-Grail

- An Explanation Of The Vulgate Cycle - Timeless Myths

- (in French)The legend of King Arthur on the Bibliothèque Nationale de France website( "flip-book" exhibitions:Lancelot-Graal,Histoire de Saint Graal,Histoire de Merlin,Le Roman de Lancelot,byLa Quête du Graal,La mort du roi Arthur)

- (in French)Bibliography on the Archives de Littérature Médiévale