Wiley Rutledge Supreme Court nomination

| Wiley Rutledge Supreme Court nomination | |

|---|---|

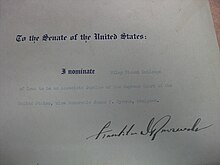

Rutledge's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, signed by Roosevelt | |

| Nominee | Wiley Rutledge |

| Nominated by | Franklin D. Roosevelt(president of the United States) |

| Succeeding | James F. Byrnes(associate justice) |

| Date nominated | January 11, 1943 |

| Date confirmed | February 8, 1943 |

| Outcome | Confirmed by theU.S. Senate |

| Vote of subcommittee of theSenate Judiciary Committee | |

| Result | Reported favorably |

| Vote of the Senate Judiciary Committee | |

| Votes in favor | 11 |

| Votes against | 0 |

| Not voting | 4 |

| Result | Reported favorably |

| Senate confirmation vote | |

| Result | Confirmed byvoice vote |

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

Wiley Rutledgewasnominatedto serve as anassociate justiceof theSupreme Court of the United Statesby U.S. PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelton January 11, 1943, after the resignation ofJames F. Byrnescreated a vacancy on the court. Per theConstitution of the United States,Rutledge's nomination was subject to theadvice and consentof theUnited States Senate,which holds the determinant power to confirm or reject nominations to the U.S. Supreme Court. After being favorably reported on by both a subcommittee of theSenate Committee on the Judiciaryand the full Judiciary Committee, the nomination was confirmed by the full Senate through avoice voteon February 8, 1943.

Background[edit]

In October 1942, Associate JusticeJames F. Byrnesresigned from theSupreme Court of the United States,creating the ninth and final vacancy on the Supreme Court ofFranklin D. Roosevelt's presidency.[1]Per theConstitution of the United States,thepresident of the United Statesfills Supreme Court vacancies with theadvice and consentof theUnited States Senate.

Rutledge had previously been given some consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court previous to 1942. In 1938, the well-regarded journalistIrving Brantand others encouraged Roosevelt to consider Rutledge as a successor to JusticeBenjamin N. Cardozowhen Cardozo retired in 1938. Brant appreciated Rutledge's views on legal reform and Rutledge's support for restrictions onchild labor.Brant believed that Rutledge was a youthful liberal intellectual. He also believed that Rutledge possessed the strong interpersonal skills, legal talent, and tenacity needed to persuade the Court's more moderate and conservative justices in decisions. Brant worked vigorously to amass endorsements from politicians and lawyers for the appointment of Rutledge. However, Roosevelt instead opted to appointFelix Frankfurterto fill the vacancy. While Frankfurter had been seen as thefront-runnerto fill the vacancy, Roosevelt had considered Rutledge and others before settling on him due to pressure to nominate an individual from the "western" United States (west of theMississippi River).[2]

In 1939, Rutledge was given serious consideration for appointment to the court whenLouis Brandeisretired. However,William O. Douglaswas instead selected.[2]Rutledge, however, was appointed by Roosevelt that year to theUnited States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbiawith the advice and consent of the United States Senate.[3]He would not be given serious consideration as a candidate for the Supreme Court for any of the four vacancies to arise between then and Byrne's 1943 resignation.[2]

Selection of Rutledge[edit]

As a result of Roosevelt's many previous appointments to the Court, there was "no obvious successor, no obvious political debt to be paid", according to the scholarHenry J. Abraham.[4]Some, including JusticesFelix FrankfurterandHarlan F. Stone,encouraged Roosevelt to appoint the distinguished juristLearned Hand.[4]Frankfurter, with what Abraham called "not uncharacteristic overkill", lobbied with particular vigor on Hand's behalf: Roosevelt noted that he had received pleas to appoint Hand from "twenty [people], and every one of them a messenger from Felix Frankfurter" in a single day.[4]But the president was uncomfortable appointing the seventy-one-year-old Hand due to his age. Roosevelt had previously cited the advanced age of Supreme Court justices to justifyhis 1937 proposal to expand the Courtand he feared that he would appear hypocritical if he appointed an elderly jurist himself.[5]

Francis Biddle,theattorney general,was unwilling to accept an appointment himself. Roosevelt asked Biddle to search for a suitable nominee.[1]: 292 A number of candidates were considered, including federal judgeJohn J. Parker,Solicitor GeneralCharles Fahy,U.S. SenatorAlben W. Barkley,andDean Acheson.[4]But the journalistDrew Pearsonsoon brought up another possibility, who he identified as "the candidate of Chief Justice Stone" in his columns and radio broadcasts: Wiley Rutledge.[5]

Irving Brant also again promoted Rutledge as a candidate for the court. Brant worked relentlessly to campaign for Roosevelt to appoint Rutledge. Brant solicited endorsements of Rutledge from politicians and lawyers and even paid a visit to Roosevelt to promote Rutledge as a candidate.[2]Brant's avid support for the appointment of Rutledge was fueled by strong impression that Rutledge had given Brant. Brant admired how Rutledge had publicly criticized the president of theAmerican Bar Associationafter the president had defended decisions by the Supreme Court decision which stuck down limitations on child labor. Brant successfully directed Roosevelt's attention to Rutledge, in part, by touting him as the most likely candidate from a state west of the Mississippi River to support the principles of Roosevelt'sNew Deal.[6]A strong reason for Brant's avid support for the appointment of Rutledge was the strong impression that Rutledge had given Brant. Brant admired how Rutledge had publicly criticized the president of theAmerican Bar Associationafter the president had defended decisions by the Supreme Court decision which stuck down limitations on child labor.[6]Additionally, Brant successfully directed Roosevelt's attention to Rutledge, in part, by touting him as the most likely candidate from a state west of theMississippi Riverto support the principles of Roosevelt'sNew Deal.[6]

Rutledge was considered about the workload of the position,[2]and had no desire to be nominated to the Supreme Court, but his friends nonetheless wrote to Roosevelt and Biddle on his behalf.[5]He wrote to Biddle disclaiming all interest in the position, and he admonished his friends with the words: "For God's sake, don't do anything about stirring up the matter! I am uncomfortable enough as it is."[5]Still, Rutledge's supporters, most notably Irving Brant, continued to lobby the White House to nominate him, and Rutledge stated in private that he would not decline the nomination if Roosevelt offered it to him.[5][4]

When Attorney General Biddle inquired with Supreme Court JusticesHugo Black,and William O. Douglas, andHarlan Stoneabout who they advised be appointed, each named Rutledge as the best among the candidates. Black and Douglas were particularly enthusiastic towards Rutledge joining them on the court.[2]Biddle directed his assistantHerbert Wechslerto review the judicial records of Rutledge and several other candidates for the vacancy. Wechsler's report convinced Biddle that Rutledge's judicial opinions were "a bit pedestrian" but nonetheless "sound".[2][5]Biddle, joined by Roosevelt loyalists such as Douglas, SenatorGeorge W. Norris,and JusticeFrank Murphy,thus recommended to the president that Rutledge be appointed.[1]: 292

After meeting with Rutledge at the White House and being convinced by Biddle that the judge's judicial philosophy was fully aligned with his own, Roosevelt agreed to appoint Rutledge.[4]: 186 Despite having appointed him years earlier to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Roosevelt had never before met Rutledge.[6]According to the scholar Fred L. Israel, Roosevelt found Rutledge to be "a liberal New Dealer who combined the president's respect for the academic community with four years of service on a leading federal appellate court".[7]Additionally, the fact that Rutledge was a Westerner weighed in his favor.[1]: 292 The president told his nominee: "Wiley, we had a number of candidates for the Court who were highly qualified, but they didn't re geography—you have that".[7]: 1318 Roosevelt also remarked to Wiley, who had lived inColorado,Iowa,Kentucky,Missouri,New Mexico,North Carolina,andTennesseeat different points in his life, "You have a lot of geography."[2]

Roosevelt formally nominated Rutledge, who was then forty-eight years old, to the Supreme Court on January 11, 1943.[8]Rutledge was the only of Roosevelt's nominees to the Supreme Court that had experience serving as a member of aUnited States courts of appeals.[9]

Judiciary Committee review[edit]

Subcommittee[edit]

A subcommittee of theSenate Committee on the Judiciary(Judiciary Committee) which was chaired by SenatorJoseph C. O'Mahoneyreviewed the nomination.[10]A single hearing was held on January 22, 1943.[11]The hearing was a public hearing.[12]In the hearing, the subcommittee heard from lawyerEdmond C. Fletcher.Along withreal estate developerJohn T. Risher,Fletcher had been urging the committee to examine the disposition of Rutledge as a justice in cases involving them that Rutledge had heard while sitting on theUnited States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.[13]

The subcommittee gave its approval to the nomination.[10]This vote was announced by O'Mahoney on January 28, 1943. While they had been urged by Fletcher and Risher to hold further hearings, the subcommittee voted against this and instead approved the nomination without conducting further hearings. The subcommittee wrote a favorable report for presentation to the full Judiciary Committee.[14]

Full Judiciary Committee[edit]

The Judiciary Committee voted on February 1, 1943, to approve Rutledge's nomination; the vote was 11–0, with four abstentions.[10]Those four senators—North Dakota'sWilliam Langer,West Virginia'sChapman Revercomb,Montana'sBurton K. Wheeler,and Michigan'sHomer S. Ferguson—abstained due to uneasiness about Rutledge's support for Roosevelt's 1937 court-expansion plan.[5]Ferguson later spoke with Rutledge and indicated that his concerns had been resolved, but Wheeler, who had strongly opposed Roosevelt's efforts to enlarge the Court, said that he would vote against the nomination when it came before the full Senate.[5]

Confirmation vote[edit]

The only senator to speak on the Senate floor in opposition to Rutledge's nomination was William Langer.[5]Langer cited Ruteledge's lack of experience practicing law as alawyer.[15]He characterized Rutledge as "a man who, so far as I can ascertain, never practiced law inside a courtroom or, so far as I know, seldom even visited one until he came to take a seat on the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia" and commented that "[t]he Court is not without a professor or two already."[5]The Senate overwhelmingly confirmed Rutledge by avoice voteon February 8, 1943,[16]and he subsequently took theoath of officeon February 15.[17]

See also[edit]

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Supreme Court candidates

- List of federal judges appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt

- List of nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States

References[edit]

- ^abcdAbraham, Henry J.(February 1983)."A Bench Happily Filled: Some Historical Reflections on the Supreme Court Appointment Process".Judicature.66:292, 294.

- ^abcdefghGreen, Craig (2006)."Wiley Rutledge, Executive Detention, and Judicial Conscience at War".Washington College Law Review.84(1).Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^"Previous Associate Justices: Wiley B. Rutledge, 1943-1949".Supreme Court Historical Society.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^abcdefAbraham, Henry J.(2008).Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II.Lanham, Maryland:Rowman & Littlefield.p. 186.ISBN978-0-7425-5895-3.

- ^abcdefghijFerren, John M.(2004).Salt of the Earth, Conscience of the Court: The Story of Justice Wiley Rutledge.Chapel Hill, North Carolina:University of North Carolina Press.pp. 208–211, 213, 216–217, 220–221.ISBN978-0-8078-2866-3.

- ^abcdFerren, John M."Justice Wiley Rutledge: Court of Appeals Years – and After"(PDF).dcchs.org.Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^abIsrael, Fred L. (1997)."Wiley Rutledge".In Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.).The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions.Vol. 4. New York:Chelsea House.p. 1318.ISBN978-0-7910-1377-9.

- ^Cushman, Clare, ed. (2013).Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies.Thousand Oaks, California:CQ Press.p. 375.ISBN978-1-60871-832-0.

- ^"Nominations".Newspapers.Lancaster New Era. The Associated Press. January 11, 1943.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^abc"Senate Committee Favors Rutledge".Fort Worth Star-Telegram.February 1, 1943. p. 2.RetrievedDecember 18,2021.

- ^McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018)."Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President"(PDF).Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.RetrievedMarch 9,2022.

- ^"Rutledge Hearing Called".Newspapers.Evening Star. January 14, 1943.Retrieved26 October2022.

- ^"Protesters Delay Rutledge Hearing".The Idaho Statesman. The Associated Press. January 23, 1943.Retrieved26 October2022– via Newspapers.

- ^"Subcommittee OK's Rutledge".The Courier. The Associated Press. January 28, 1943.Retrieved26 October2022– via Newspapers.

- ^"Nomination of Rutledge is Confirmed".Newspapers.Greeley Daily Tribune. The Associated Press. February 8, 1943.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^Hall, Timothy L. (2001).Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary.New York:Facts on File.p. 331.ISBN978-0-8160-4194-7.

- ^Biskupic, Joan;Witt, Elder (1997).Guide to the U.S. Supreme Court.Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC:Congressional Quarterly.p. 938.ISBN978-1-56802-130-0.