Wolf

| Wolf Temporal range:

Middle Pleistocene– present(400,000–0YBP) | |

|---|---|

| |

Eurasian wolf(Canis lupus lupus) atPolar Parkin Bardu, Norway

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Canis lupus | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Global wolf range based on IUCN's 2023 assessment.[1] | |

Thewolf(Canis lupus;[b]pl.:wolves), also known as thegray wolforgrey wolf,is a largecaninenative toEurasiaandNorth America.More than thirtysubspecies ofCanis lupushave been recognized, including thedoganddingo,though gray wolves, as popularly understood, only comprise naturally-occurring wild subspecies. The wolf is the largestextantmember of the familyCanidae,and is further distinguished from otherCanisspecies by its less pointed ears and muzzle, as well as a shorter torso and a longer tail. The wolf is nonetheless related closely enough to smallerCanisspecies, such as thecoyoteand thegolden jackal,to produce fertilehybridswith them. The wolf's fur is usually mottled white, brown, gray, and black, although subspecies in the arctic region may be nearly all white.

Of all members of thegenusCanis,the wolf is mostspecializedforcooperativegame huntingas demonstrated by its physical adaptations to tackling large prey, its moresocial nature,and its highly advancedexpressive behaviour,including individual or grouphowling.It travels innuclear familiesconsisting of amated pairaccompanied by their offspring. Offspring may leave to form their ownpackson the onset of sexual maturity and in response to competition for food within the pack. Wolves are alsoterritorial,and fights over territory are among the principal causes of mortality. The wolf is mainly acarnivoreand feeds on large wildhooved mammalsas well as smaller animals, livestock,carrion,and garbage. Single wolves or mated pairs typically have higher success rates in hunting than do large packs.Pathogensand parasites, notably therabies virus,may infect wolves.

The global wild wolf population was estimated to be 300,000 in 2003 and is considered to be ofLeast Concernby theInternational Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN). Wolves have a long history of interactions with humans, having been despised and hunted in mostpastoralcommunities because of their attacks on livestock, while conversely being respected in someagrarianandhunter-gatherersocieties. Although the fear of wolves exists in many human societies, the majority of recorded attacks on people have been attributed to animals suffering fromrabies.Wolf attackson humans are rare because wolves are relatively few, live away from people, and have developed a fear of humans because of their experiences with hunters, farmers, ranchers, and shepherds.

Etymology

The English "wolf" stems from theOld Englishwulf,which is itself thought to be derived from theProto-Germanic*wulfaz.TheProto-Indo-European root*wĺ̥kʷosmay also be the source of theLatinword for the animallupus(*lúkʷos).[4][5]The name "gray wolf" refers to the grayish colour of the species.[6]

Since pre-Christian times,Germanic peoplessuch as theAnglo-Saxonstook onwulfas aprefixorsuffixin their names. Examples include Wulfhere ( "Wolf Army" ), Cynewulf ( "Royal Wolf" ), Cēnwulf ( "Bold Wolf" ), Wulfheard ( "Wolf-hard" ), Earnwulf ( "Eagle Wolf" ), Wulfstān ( "Wolf Stone" ) Æðelwulf ( "Noble Wolf" ), Wolfhroc ( "Wolf-Frock" ), Wolfhetan ( "Wolf Hide" ), Scrutolf ( "Garb Wolf" ), Wolfgang ( "Wolf Gait" ) and Wolfdregil ( "Wolf Runner" ).[7]

Taxonomy

| Canine phylogeny with ages of divergence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram and divergence of the gray wolf (including the domestic dog) among its closest extant relatives[8] |

In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologistCarl Linnaeuspublished in hisSystema Naturaethebinomial nomenclature.[3]Canisis the Latin word meaning "dog",[9]and under thisgenushe listed the doglike carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, andjackals.He classified the domestic dog asCanis familiaris,and the wolf asCanis lupus.[3]Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its "cauda recurvata" (upturning tail) which is not found in any othercanid.[10]

Subspecies

In the third edition ofMammal Species of the Worldpublished in 2005, themammalogistW. Christopher Wozencraftlisted underC. lupus36 wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies:familiaris(Linnaeus, 1758) anddingo(Meyer, 1793). Wozencraft includedhallstromi—theNew Guinea singing dog—as ataxonomic synonymfor thedingo.Wozencraft referred to a 1999mitochondrial DNA(mtDNA) study as one of the guides in forming his decision, and listed the 38subspecies ofC. lupusunder the biologicalcommon nameof "wolf", thenominate subspeciesbeing theEurasian wolf(C. l. lupus) based on thetype specimenthat Linnaeus studied in Sweden.[11]Studies usingpaleogenomictechniques reveal that the modern wolf and the dog aresister taxa,as modern wolves are not closely related to the population of wolves that was firstdomesticated.[12]In 2019, a workshop hosted by theIUCN/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea singing dog and the dingo to beferalCanis familiaris,and therefore should not be assessed for theIUCN Red List.[13]

Evolution

Thephylogeneticdescent of the extant wolfC. lupusfrom the earlierC. mosbachensis(which in turn descended fromC. etruscus) is widely accepted.[14]Among the oldest fossils of the modern grey wolf is from Ponte Galeria in Italy, dating to 406,500 ± 2,400 years ago,[15],though material from Cripple Creek Sump in Alaska may be considerably older, around 1 million years old.[16]Considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves by theLate Pleistocene.Many Late Pleistocene wolf populations had more robust skulls and teeth than modern wolves, often with a shortenedsnout,a pronounced development of thetemporalismuscle, and robustpremolars.It is proposed that these features were specialized adaptations for the processing of carcass and bone associated with the hunting and scavenging ofPleistocene megafauna.Compared with modern wolves, some Pleistocene wolves showed an increase in tooth breakage similar to that seen in the extinctdire wolf.This suggests they either often processed carcasses, or that they competed with other carnivores and needed to consume their prey quickly. Compared with those found in the modernspotted hyena,the frequency and location of tooth fractures in these wolves indicates they were habitual bone crackers.[17]

Genomicstudies suggest modern wolves and dogs descend from a common ancestral wolf population.[18][19][20]A 2021 study found that theHimalayan wolfand theIndian plains wolfare part of alineagethat isbasalto other wolves andsplitfrom them 200,000 years ago.[21]Other wolves appear to share most of their common ancestry much more recently, within the last 23,000 years (around the peak and the end of theLast Glacial Maximum), originating fromSiberia[22]orBeringia.[23]While some sources have suggested that this was a consequence of apopulation bottleneck,[23]other studies have suggested that this a result ofgene flowhomogenising ancestry.[22]

A 2016 genomic study suggests that Old World and New World wolves split around 12,500 years ago followed by thedivergenceof the lineage that led to dogs from other Old World wolves around 11,100–12,300 years ago.[20]An extinctLate Pleistocene wolfmay have been the ancestor of the dog,[24][17]with the dog's similarity to the extant wolf being the result ofgenetic admixturebetween the two.[17]The dingo,Basenji,Tibetan Mastiffand Chinese indigenous breeds are basal members of the domestic dog clade. The divergence time for wolves in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia is estimated to be fairly recent at around 1,600 years ago. Among New World wolves, theMexican wolfdiverged around 5,400 years ago.[20]

Admixture with other canids

In the distant past, there wasgene flowbetweenAfrican wolves,golden jackals,and gray wolves. The African wolf is a descendant of a genetically admixed canid of 72% wolf and 28% Ethiopian wolf ancestry. One African wolf from the EgyptianSinai Peninsulashowed admixture with Middle Eastern gray wolves and dogs.[25]There is evidence of gene flow between golden jackals and Middle Eastern wolves, less so with European and Asian wolves, and least with North American wolves. This indicates the golden jackal ancestry found in North American wolves may have occurred before the divergence of the Eurasian and North American wolves.[26]

The common ancestor of the coyote and the wolf admixed with aghost populationof an extinct unidentified canid. This canid was genetically close to thedholeand evolved after the divergence of theAfrican hunting dogfrom the other canid species. The basal position of thecoyotecompared to the wolf is proposed to be due to the coyote retaining more of the mitochondrial genome of this unidentified canid.[25]Similarly, a museum specimen of a wolf from southern China collected in 1963 showed a genome that was 12–14% admixed from this unknown canid.[27]In North America, some coyotes and wolves show varying degrees of pastgenetic admixture.[26]

In more recent times, some maleItalian wolvesoriginated from dog ancestry, which indicates female wolves will breed with male dogs in the wild.[28]In theCaucasus Mountains,ten percent of dogs includinglivestock guardian dogs,are first generation hybrids.[29]Although mating between golden jackals and wolves has never been observed, evidence ofjackal-wolf hybridizationwas discovered through mitochondrial DNA analysis of jackals living in the Caucasus Mountains[29]and in Bulgaria.[30]In 2021, a genetic study found that the dog's similarity to the extant gray wolf was the result of substantial dog-into-wolfgene flow,with little evidence of the reverse.[31]

Description

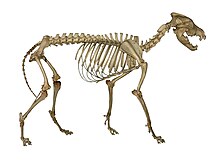

The wolf is the largest extant member of the familyCanidae,[32]and is further distinguished from coyotes and jackals by a broader snout, shorter ears, a shorter torso and a longer tail.[33][32]It is slender and powerfully built, with a large, deeply descendingrib cage,a sloping back, and a heavily muscled neck.[34]The wolf's legs are moderately longer than those of other canids, which enables the animal to move swiftly, and to overcome the deep snow that covers most of its geographical range in winter.[35]The ears are relatively small and triangular.[34]The wolf's head is large and heavy, with a wide forehead, strong jaws and a long, blunt muzzle.[36]The skull is 230–280 mm (9–11 in) in length and 130–150 mm (5–6 in) in width.[37]The teeth are heavy and large, making them better suited to crushing bone than those of other canids, though they are not as specialized as those found inhyenas.[38][39]Itsmolarshave a flat chewing surface, but not to the same extent as the coyote, whose diet contains more vegetable matter.[40]Females tend to have narrower muzzles and foreheads, thinner necks, slightly shorter legs, and less massive shoulders than males.[41]

Adult wolves measure 105–160 cm (41–63 in) in length and 80–85 cm (31–33 in) at shoulder height.[36]The tail measures 29–50 cm (11–20 in) in length, the ears90–110 mm (3+1⁄2–4+3⁄8in) in height, and the hind feet are220–250 mm (8+5⁄8–9+7⁄8in).[42]The size and weight of the modern wolf increases proportionally with latitude in accordance withBergmann's rule.[43]The mean body mass of the wolf is 40 kg (88 lb), the smallest specimen recorded at 12 kg (26 lb) and the largest at 79.4 kg (175 lb).[44][36]On average, European wolves weigh 38.5 kg (85 lb), North American wolves 36 kg (79 lb), and Indian andArabian wolves25 kg (55 lb).[45]Females in any given wolf population typically weigh 2.3–4.5 kg (5–10 lb) less than males. Wolves weighing over 54 kg (119 lb) are uncommon, though exceptionally large individuals have been recorded in Alaska and Canada.[46]In central Russia, exceptionally large males can reach a weight of 69–79 kg (152–174 lb).[42]

Pelage

The wolf has very dense and fluffy winter fur, with a shortundercoatand long, coarseguard hairs.[36]Most of the undercoat and some guard hairs are shed in spring and grow back in autumn.[45]The longest hairs occur on the back, particularly on the front quarters and neck. Especially long hairs grow on the shoulders and almost form a crest on the upper part of the neck. The hairs on the cheeks are elongated and form tufts. The ears are covered in short hairs and project from the fur. Short, elastic and closely adjacent hairs are present on the limbs from theelbowsdown to thecalcaneal tendons.[36]The winter fur is highly resistant to the cold. Wolves in northern climates can rest comfortably in open areas at −40 °C (−40 °F) by placing their muzzles between the rear legs and covering their faces with their tail. Wolf fur provides better insulation than dog fur and does not collect ice when warm breath is condensed against it.[45]

In cold climates, the wolf can reduce the flow of blood near its skin to conserve body heat. The warmth of the foot pads is regulated independently from the rest of the body and is maintained at just abovetissue-freezingpoint where the pads come in contact with ice and snow.[47]In warm climates, the fur is coarser and scarcer than in northern wolves.[36]Female wolves tend to have smoother furred limbs than males and generally develop the smoothest overall coats as they age. Older wolves generally have more white hairs on the tip of the tail, along the nose, and on the forehead. Winter fur is retained longest by lactating females, although with some hair loss around their teats.[41]Hair length on the middle of the back is60–70 mm (2+3⁄8–2+3⁄4in), and the guard hairs on the shoulders generally do not exceed90 mm (3+1⁄2in), but can reach110–130 mm (4+3⁄8–5+1⁄8in).[36]

A wolf's coat colour is determined by its guard hairs. Wolves usually have some hairs that are white, brown, gray and black.[48]The coat of the Eurasian wolf is a mixture ofochreous(yellow to orange) andrustyochreous (orange/red/brown) colours with light gray. The muzzle is pale ochreous gray, and the area of the lips, cheeks, chin, and throat is white. The top of the head, forehead, under and between the eyes, and between the eyes and ears is gray with a reddish film. The neck is ochreous. Long, black tips on the hairs along the back form a broad stripe, with black hair tips on the shoulders, upper chest and rear of the body. The sides of the body, tail, and outer limbs are a pale dirty ochreous colour, while the inner sides of the limbs, belly, and groin are white. Apart from those wolves which are pure white or black, these tones vary little across geographical areas, although the patterns of these colours vary between individuals.[49]

In North America, the coat colours of wolves followGloger's rule,wolves in the Canadian arctic being white and those in southern Canada, the U.S., and Mexico being predominantly gray. In some areas of theRocky Mountainsof Alberta and British Columbia, the coat colour is predominantly black, some being blue-gray and some with silver and black.[48]Differences in coat colour between sexes is absent in Eurasia;[50]females tend to have redder tones in North America.[51]Black-coloured wolvesin North America acquired their colour from wolf-dog admixture after the first arrival of dogs across the Bering Strait 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[52]Research into the inheritance of white colour from dogs into wolves has yet to be undertaken.[53]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Wolves occur across Eurasia and North America. However, deliberate human persecution because of livestock predation and fear of attacks on humans has reduced the wolf's range to about one-third of its historic range; the wolf is nowextirpated(locally extinct) from much of its range in Western Europe, the United States and Mexico, and completely in theBritish Islesand Japan. In modern times, the wolf occurs mostly in wilderness and remote areas. The wolf can be found between sea level and 3,000 m (9,800 ft). Wolves live in forests, inlandwetlands,shrublands,grasslands(including Arctictundra),pastures,deserts, and rocky peaks on mountains.[1]Habitat use by wolves depends on the abundance of prey, snow conditions, livestock densities, road densities, human presence andtopography.[40]

Diet

Like all land mammals that arepack hunters,the wolf feeds predominantly onungulatesthat can be divided into large size 240–650 kg (530–1,430 lb) and medium size 23–130 kg (51–287 lb), and have a body mass similar to that of the combined mass of thepackmembers.[54][55]The wolf specializes in preying on the vulnerable individuals of large prey,[40]with a pack of 15 able to bring down an adultmoose.[56]The variation in diet between wolves living on different continents is based on the variety of hoofed mammals and of available smaller and domesticated prey.[57]

In North America, the wolf's diet is dominated by wild large hoofed mammals (ungulates) and medium-sized mammals. In Asia and Europe, their diet is dominated by wild medium-sized hoofed mammals and domestic species. The wolf depends on wild species, and if these are not readily available, as in Asia, the wolf is more reliant on domestic species.[57]Across Eurasia, wolves prey mostly onmoose,red deer,roe deerandwild boar.[58]In North America, important range-wide prey areelk,moose,caribou,white-tailed deerandmule deer.[59]Prior to their extirpation from North America,wild horseswere among the most frequently consumed prey of North American wolves.[60]Wolves can digest their meal in a few hours and can feed several times in one day, making quick use of large quantities of meat.[61]A well-fed wolf stores fat under the skin, around the heart, intestines, kidneys, and bone marrow, particularly during the autumn and winter.[62]

Nonetheless, wolves are not fussy eaters. Smaller-sized animals that may supplement their diet includerodents,hares,insectivoresand smaller carnivores. They frequently eatwaterfowland their eggs. When such foods are insufficient, they prey onlizards,snakes,frogs,and large insects when available.[63]Wolves in some areas may consume fish and even marine life.[64][65][66]Wolves also consume some plant material. In Europe, they eat apples, pears,figs,melons,berriesandcherries.In North America, wolves eatblueberriesandraspberries.They also eat grass, which may provide some vitamins, but is most likely used mainly to induce vomiting to rid themselves of intestinal parasites or long guard hairs.[67]They are known to eat the berries ofmountain-ash,lily of the valley,bilberries,cowberries,European black nightshade,grain crops, and the shoots of reeds.[63]

In times of scarcity, wolves will readily eatcarrion.[63]In Eurasian areas with dense human activity, many wolf populations are forced to subsist largely on livestock and garbage.[58]As prey in North America continue to occupy suitable habitats with low human density, North American wolves eat livestock and garbage only in dire circumstances.[68]Cannibalismis not uncommon in wolves during harsh winters, when packs often attack weak or injured wolves and may eat the bodies of dead pack members.[63][69][70]

Interactions with other predators

Wolves typically dominate other canid species in areas where they both occur. In North America, incidents of wolves killing coyotes are common, particularly in winter, when coyotes feed on wolf kills. Wolves may attack coyote den sites, digging out and killing their pups, though rarely eating them. There are no records of coyotes killing wolves, though coyotes may chase wolves if they outnumber them.[71]According to a press release by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1921, the infamousCuster Wolfrelied on coyotes to accompany him and warn him of danger. Though they fed from his kills, he never allowed them to approach him.[72]Interactions have been observed in Eurasia between wolves and golden jackals, the latter's numbers being comparatively small in areas with high wolf densities.[36][71][73]Wolves also killred,Arcticandcorsac foxes,usually in disputes over carcasses, sometimes eating them.[36][74]

Brown bearstypically dominate wolf packs in disputes over carcasses, while wolf packs mostly prevail against bears when defending their den sites. Both species kill each other's young. Wolves eat the brown bears they kill, while brown bears seem to eat only young wolves.[75]Wolf interactions withAmerican black bearsare much rarer because of differences in habitat preferences. Wolves have been recorded on numerous occasions actively seeking out American black bears in their dens and killing them without eating them. Unlike brown bears, American black bears frequently lose against wolves in disputes over kills.[76]Wolves also dominate and sometimes killwolverines,and will chase off those that attempt to scavenge from their kills. Wolverines escape from wolves in caves or up trees.[77]

Wolves may interact and compete withfelids,such as theEurasian lynx,which may feed on smaller prey where wolves are present[78]and may be suppressed by large wolf populations.[79]Wolves encountercougarsalong portions of the Rocky Mountains and adjacent mountain ranges. Wolves and cougars typically avoid encountering each other by hunting at different elevations for different prey (niche partitioning). This is more difficult during winter. Wolves in packs usually dominate cougars and can steal their kills or even kill them,[80]while one-to-one encounters tend to be dominated by the cat, who likewise will kill wolves.[81]Wolves more broadly affect cougar population dynamics and distribution by dominating territory and prey opportunities and disrupting the feline's behaviour.[82]Wolf andSiberian tigerinteractions are well-documented in theRussian Far East,where tigers significantly depress wolf numbers, sometimes to the point oflocalized extinction.[83][78]

In Israel, Palestine, Central Asia and India wolves may encounterstriped hyenas,usually in disputes over carcasses. Striped hyenas feed extensively on wolf-killed carcasses in areas where the two species interact. One-to-one, hyenas dominate wolves, and may prey on them,[84]but wolf packs can drive off single or outnumbered hyenas.[85][86]There is at least one case in Israel of a hyena associating and cooperating with a wolf pack.[87]

Infections

Viral diseasescarried by wolves include:rabies,canine distemper,canine parvovirus,infectious canine hepatitis,papillomatosis,andcanine coronavirus.In wolves, theincubation periodfor rabies is eight to 21 days, and results in the host becoming agitated, deserting its pack, and travelling up to 80 km (50 mi) a day, thus increasing the risk of infecting other wolves. Although canine distemper is lethal in dogs, it has not been recorded to kill wolves, except in Canada and Alaska. The canine parvovirus, which causes death bydehydration,electrolyte imbalance,andendotoxicshock orsepsis,is largely survivable in wolves, but can be lethal to pups.[88]Bacterial diseasescarried by wolves include:brucellosis,Lyme disease,leptospirosis,tularemia,bovine tuberculosis,[89]listeriosisandanthrax.[90]Although lyme disease can debilitate individual wolves, it does not appear to significantly affect wolf populations. Leptospirosis can be contracted through contact with infected prey or urine, and can causefever,anorexia,vomiting,anemia,hematuria,icterus,and death.[89]

Wolves are often infested with a variety ofarthropodexoparasites, includingfleas,ticks,lice,andmites.The most harmful to wolves, particularly pups, is the mange mite (Sarcoptes scabiei),[91]though they rarely develop full-blownmange,unlike foxes.[36]Endoparasites known to infect wolves include:protozoansandhelminths(flukes,tapeworms,roundwormsandthorny-headed worms). Most fluke species reside in the wolf's intestines. Tapeworms are commonly found in wolves, which they get though their prey, and generally cause little harm in wolves, though this depends on the number and size of the parasites, and the sensitivity of the host. Symptoms often includeconstipation,toxic andallergic reactions,irritation of theintestinal mucosa,andmalnutrition.Wolves can carry over 30 roundworm species, though most roundworm infections appear benign, depending on the number of worms and the age of the host.[91]

Behaviour

Social structure

The wolf is asocial animal.[36]Its populations consist of packs and lone wolves, most lone wolves being temporarily alone while they disperse from packs to form their own or join another one.[92]The wolf's basic social unit is thenuclear familyconsisting of amated pairaccompanied by their offspring.[36]The average pack size in North America is eight wolves and in Europe 5.5 wolves.[43]The average pack across Eurasia consists of a family of eight wolves (two adults, juveniles, and yearlings),[36]or sometimes two or three such families,[40]with examples of exceptionally large packs consisting of up to 42 wolves being known.[93]Cortisollevels in wolves rise significantly when a pack member dies, indicating the presence of stress.[94]During times of prey abundance caused by calving or migration, different wolf packs may join together temporarily.[36]

Offspring typically stay in the pack for 10–54 months before dispersing.[95]Triggers for dispersal include the onset ofsexual maturityand competition within the pack for food.[96]The distance travelled by dispersing wolves varies widely; some stay in the vicinity of the parental group, while other individuals may travel great distances of upwards of 206 km (128 mi), 390 km (240 mi), and 670 km (420 mi) from their natal (birth) packs.[97]A new pack is usually founded by an unrelated dispersing male and female, travelling together in search of an area devoid of other hostile packs.[98]Wolf packs rarely adopt other wolves into their fold and typically kill them. In the rare cases where other wolves are adopted, the adoptee is almost invariably an immature animal of one to three years old, and unlikely to compete for breeding rights with the mated pair. This usually occurs between the months of February and May. Adoptee males may mate with an available pack female and then form their own pack. In some cases, a lone wolf is adopted into a pack to replace a deceased breeder.[93]

Wolves areterritorialand generally establish territories far larger than they require to survive assuring a steady supply of prey. Territory size depends largely on the amount of prey available and the age of the pack's pups. They tend to increase in size in areas with low prey populations,[99]or when the pups reach the age of six months when they have the same nutritional needs as adults.[100]Wolf packs travel constantly in search of prey, covering roughly 9% of their territory per day, on average 25 km/d (16 mi/d). The core of their territory is on average 35 km2(14 sq mi) where they spend 50% of their time.[99]Prey density tends to be much higher on the territory's periphery. Wolves tend to avoid hunting on the fringes of their range to avoid fatal confrontations with neighbouring packs.[101]The smallest territory on record was held by a pack of six wolves in northeastern Minnesota, which occupied an estimated 33 km2(13 sq mi), while the largest was held by an Alaskan pack of ten wolves encompassing 6,272 km2(2,422 sq mi).[100]Wolf packs are typically settled, and usually leave their accustomed ranges only during severe food shortages.[36]Territorial fights are among the principal causes of wolf mortality, one study concluding that 14–65% of wolf deaths in Minnesota and theDenali National Park and Preservewere due to other wolves.[102]

Communication

Wolves communicate using vocalizations, body postures, scent, touch, and taste.[103]The phases of the moon have no effect on wolf vocalization, and despite popular belief, wolves do not howl at the Moon.[104]Wolveshowlto assemble the pack usually before and after hunts, to pass on an alarm particularly at a den site, to locate each other during a storm, while crossing unfamiliar territory, and to communicate across great distances.[105]Wolf howls can under certain conditions be heard over areas of up to 130 km2(50 sq mi).[40]Other vocalizations includegrowls,barksand whines. Wolves do not bark as loudly or continuously as dogs do in confrontations, rather barking a few times and then retreating from a perceived danger.[106]Aggressive or self-assertive wolves are characterized by their slow and deliberate movements, high bodypostureand raisedhackles,while submissive ones carry their bodies low, flatten their fur, and lower their ears and tail.[107]

Scent marking involves urine, feces, andpreputialand anal gland scents. This is more effective at advertising territory than howling and is often used in combination with scratch marks. Wolves increase their rate of scent marking when they encounter the marks of wolves from other packs. Lone wolves will rarely mark, but newly bonded pairs will scent mark the most.[40]These marks are generally left every 240 m (260 yd) throughout the territory on regular travelways and junctions. Such markers can last for two to three weeks,[100]and are typically placed near rocks, boulders, trees, or the skeletons of large animals.[36]Raised legurinationis considered to be one of the most important forms of scent communication in the wolf, making up 60–80% of all scent marks observed.[108]

Reproduction

Wolves aremonogamous,mated pairs usually remaining together for life. Should one of the pair die, another mate is found quickly.[109]With wolves in the wild, inbreeding does not occur where outbreeding is possible.[110]Wolves become mature at the age of two years and sexually mature from the age of three years.[109]The age of first breeding in wolves depends largely on environmental factors: when food is plentiful, or when wolf populations are heavily managed, wolves can rear pups at younger ages to better exploit abundant resources. Females are capable of producing pups every year, onelitterannually being the average.[111]Oestrusandrutbegin in the second half of winter and lasts for two weeks.[109]

Dens are usually constructed for pups during the summer period. When building dens, females make use of natural shelters like fissures in rocks, cliffs overhanging riverbanks and holes thickly covered by vegetation. Sometimes, the den is the appropriated burrow of smaller animals such as foxes, badgers or marmots. An appropriated den is often widened and partly remade. On rare occasions, female wolves dig burrows themselves, which are usually small and short with one to three openings. The den is usually constructed not more than 500 m (550 yd) away from a water source. It typically faces southwards where it can be better warmed by sunlight exposure, and the snow can thaw more quickly. Resting places, play areas for the pups, and food remains are commonly found around wolf dens. The odor of urine and rotting food emanating from the denning area often attracts scavenging birds likemagpiesandravens.Though they mostly avoid areas within human sight, wolves have been known to nest neardomiciles,pavedroadsandrailways.[112]During pregnancy, female wolves remain in a den located away from the peripheral zone of their territories, where violent encounters with other packs are less likely to occur.[113]

Thegestation periodlasts 62–75 days with pups usually being born in the spring months or early summer in very cold places such as on the tundra. Young females give birth to four to five young, and older females from six to eight young and up to 14. Their mortality rate is 60–80%.[114]Newborn wolf pups look similar toGerman Shepherd Dogpups.[115]They are born blind and deaf and are covered in short soft grayish-brown fur. They weigh300–500 g (10+1⁄2–17+3⁄4oz) at birth and begin to see after nine to 12 days. The milk canines erupt after one month. Pups first leave the den after three weeks. At one-and-a-half months of age, they are agile enough to flee from danger. Mother wolves do not leave the den for the first few weeks, relying on the fathers to provide food for them and their young. Pups begin to eat solid food at the age of three to four weeks. They have a fast growth rate during their first four months of life: during this period, a pup's weight can increase nearly 30 times.[114][116]Wolf pups begin play-fighting at the age of three weeks, though unlike young coyotes and foxes, their bites are gentle and controlled. Actual fights to establish hierarchy usually occur at five to eight weeks of age. This is in contrast to young coyotes and foxes, which may begin fighting even before the onset of play behaviour.[117]By autumn, the pups are mature enough to accompany the adults on hunts for large prey.[113]

Hunting and feeding

Single wolves or mated pairs typically have higher success rates in hunting than do large packs; single wolves have occasionally been observed to kill large prey such as moose,bisonandmuskoxenunaided.[118][119]The size of a wolf hunting pack is related to the number of pups that survived the previous winter, adult survival, and the rate of dispersing wolves leaving the pack. The optimal pack size for hunting elk is four wolves, and for bison a large pack size is more successful.[120]Wolves move around their territory when hunting, using the same trails for extended periods.[121]Wolves are nocturnal predators. During the winter, a pack will commence hunting in the twilight of early evening and will hunt all night, traveling tens of kilometres. Sometimes hunting large prey occurs during the day. During the summer, wolves generally tend to hunt individually, ambushing their prey and rarely giving pursuit.[122]

When hunting large gregarious prey, wolves will try to isolate an individual from its group.[123]If successful, a wolf pack can bring down game that will feed it for days, but one error in judgement can lead to serious injury or death. Most large prey have developed defensive adaptations and behaviours. Wolves have been killed while attempting to bring down bison, elk, moose, muskoxen, and even by one of their smallest hoofed prey, the white-tailed deer. With smaller prey likebeaver,geese, and hares, there is no risk to the wolf.[124]Although people often believe wolves can easily overcome any of their prey, their success rate in hunting hoofed prey is usually low.[125]

The wolf must give chase and gain on its fleeing prey, slow it down by biting through thick hair and hide, and then disable it enough to begin feeding.[124]Wolves may wound large prey and then lie around resting for hours before killing it when it is weaker due to blood loss, thereby lessening the risk of injury to themselves.[126]With medium-sized prey, such as roe deer orsheep,wolves kill bybiting the throat,severing nerve tracks and thecarotid artery,thus causing the animal to die within a few seconds to a minute. With small,mouselikeprey, wolves leap in a high arc and immobilize it with their forepaws.[127]

Once prey is brought down, wolves begin to feed excitedly, ripping and tugging at the carcass in all directions, and bolting down large chunks of it.[128]The breeding pair typically monopolizes food to continue producing pups. When food is scarce, this is done at the expense of other family members, especially non-pups.[129]Wolves typically commence feeding by gorging on the larger internal organs, like theheart,liver,lungs,andstomachlining. Thekidneysandspleenare eaten once they are exposed, followed by the muscles.[130]A wolf can eat 15–19% of its body weight in one sitting.[62]

Status and conservation

The global wild wolf population in 2003 was estimated at 300,000.[131]Wolf population declines have been arrested since the 1970s. This has fostered recolonization and reintroduction in parts of its former range as a result of legal protection, changes in land use, and rural human population shifts to cities. Competition with humans for livestock and game species, concerns over the danger posed by wolves to people, and habitat fragmentation pose a continued threat to the wolf. Despite these threats, theIUCNclassifies the wolf asLeast Concernon itsRed Listdue to its relatively widespread range and stable population. The species is listed underAppendixIIof theConvention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora(CITES), meaning international trade in the species (including parts and derivatives) is regulated. However, populations ofBhutan,India,NepalandPakistanare listed inAppendixIwhich prohibits commercial international trade in wild-sourced specimens.[1]

North America

In Canada, 50,000–60,000 wolves live in 80% of their historical range, making Canada an important stronghold for the species.[40]Under Canadian law,First Nationspeople can hunt wolves without restrictions, but others must acquire licenses for the hunting and trapping seasons. As many as 4,000 wolves may be harvested in Canada each year.[132]The wolf is a protected species in national parks under theCanada National Parks Act.[133]In Alaska, 7,000–11,000 wolves are found on 85% of the state's 1,517,733 km2(586,000 sq mi) area. Wolves may be hunted or trapped with a license; around 1,200 wolves are harvested annually.[134]

In thecontiguous United States,wolf declines were caused by the expansion of agriculture, the decimation of the wolf's main prey species like the American bison, and extermination campaigns.[40]Wolves were given protection under theEndangered Species Act(ESA) of 1973, and have since returned to parts of their former range thanks to both natural recolonizations andreintroductions in Yellowstone and Idaho.[135]Therepopulation of wolves in Midwestern United Stateshas been concentrated in theGreat Lakesstates of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan where wolves number over 4,000 as of 2018.[136]Wolves also occupy much of the northern Rocky Mountains region and the northwest, with a total population over 3,000 as of the 2020s.[137]In Mexico and parts of the southwestern United States, the Mexican and U.S. governments collaborated from 1977 to 1980 in capturing all Mexican wolves remaining in the wild to prevent their extinction and established captive breeding programs for reintroduction.[138]As of 2024, the reintroducedMexican wolfpopulation numbers over 250 individuals.[139]

Eurasia

Europe, excluding Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, has 17,000 wolves in more than 28 countries.[140]In many countries of theEuropean Union,the wolf is strictly protected under the 1979Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats(AppendixII) and the 1992Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora(AnnexII andIV). There is extensive legal protection in many European countries, although there are national exceptions.[1][141]

Wolves have been persecuted in Europe for centuries, having been exterminated inGreat Britainby 1684, inIrelandby 1770, in Central Europe by 1899, in France by the 1930s, and in much of Scandinavia by the early 1970s. They continued to survive in parts of Finland, Eastern Europe and Southern Europe.[142]Since 1980, European wolves have rebounded and expanded into parts of their former range. The decline of the traditional pastoral and rural economies seems to have ended the need to exterminate the wolf in parts of Europe.[132]As of 2016, estimates of wolf numbers include: 4,000 in the Balkans, 3,460–3,849 in theCarpathian Mountains,1,700–2,240 in theBaltic states,1,100–2,400 in theItalian peninsula,and around 2,500 in the northwestIberian peninsulaas of 2007.[140]In a study of wolf conservation in Sweden, it was found that there was little opposition between the policies of the European Union and those of the Swedish officials implementing domestic policy.[143]

In theformer Soviet Union,wolf populations have retained much of their historical range despite Soviet-era large scale extermination campaigns. Their numbers range from 1,500 in Georgia, to 20,000 in Kazakhstan and up to 45,000 in Russia.[144]In Russia, the wolf is regarded as a pest because of its attacks on livestock, and wolf management means controlling their numbers by destroying them throughout the year. Russian history over the past century shows that reduced hunting leads to an abundance of wolves.[145]The Russian government has continued to pay bounties for wolves and annual harvests of 20–30% do not appear to significantly affect their numbers.[146]

In the Middle East, only Israel and Oman give wolves explicit legal protection.[147]Israel has protected its wolves since 1954 and has maintained a moderately sized population of 150 through effective enforcement of conservation policies. These wolves have moved into neighboring countries. Approximately 300–600 wolves inhabit theArabian Peninsula.[148]The wolf also appears to be widespread in Iran.[149]Turkey has an estimated population of about 7,000 wolves.[150]Outside of Turkey, wolf populations in the Middle East may total 1,000–2,000.[147]

In southern Asia, the northern regions of Afghanistan andPakistanare important strongholds for wolves. The wolf has been protected inIndiasince 1972.[151]The Indian wolf is distributed across the states ofGujarat,Rajasthan,Haryana,Uttar Pradesh,Madhya Pradesh,Maharashtra,KarnatakaandAndhra Pradesh.[152]As of 2019, it is estimated that there are around 2,000–3,000 Indian wolves in the country.[153]In East Asia, Mongolia's population numbers 10,000–20,000. In China,Heilong gian ghas roughly 650 wolves,Xin gian ghas 10,000 andTibethas 2,000.[154]2017 evidence suggests that wolves range across all of mainland China.[155]Wolves have been historically persecuted in China[156]but have been legally protected since 1998.[157]The lastJapanese wolfwas captured and killed in 1905.[158]

Relationships with humans

In culture

In folklore, religion and mythology

The wolf is a common motif in the mythologies and cosmologies of peoples throughout its historical range. TheAncient Greeksassociated wolves withApollo,the god of light and order.[159]TheAncient Romansconnected the wolf with their god of war and agricultureMars,[160]and believed their city's founders,Romulus and Remus,were suckled by ashe-wolf.[161]Norse mythologyincludes the feared giant wolfFenrir,[162]andGeri and Freki,Odin's faithful pets.[163]

InChinese astronomy,the wolf representsSiriusand guards the heavenly gate. In China, the wolf was traditionally associated with greed and cruelty and wolf epithets were used to describe negative behaviours such as cruelty ( "wolf's heart" ), mistrust ( "wolf's look" ) and lechery ( "wolf-sex" ). In bothHinduismandBuddhism,the wolf is ridden by gods of protection. InVedicHinduism, the wolf is a symbol of the night and the daytimequailmust escape from its jaws. InTantric Buddhism,wolves are depicted as inhabitants of graveyards and destroyers of corpses.[162]

In thePawneecreation myth, the wolf was the first animal brought to Earth. When humans killed it, they were punished with death, destruction and the loss of immortality.[164]For the Pawnee, Sirius is the "wolf star" and its disappearance and reappearance signified the wolf moving to and from the spirit world. Both Pawnee andBlackfootcall theMilky Waythe "wolf trail".[165]The wolf is also an importantcrestsymbol for clans of the Pacific Northwest like theKwakwakaʼwakw.[162]

The concept of people turning into wolves, and the inverse, has been present in many cultures. OneGreek mythtells ofLycaonbeing transformed into a wolf byZeusas punishment for his evil deeds.[166]The legend of thewerewolfhas been widespread inEuropean folkloreand involves people willingly turning into wolves to attack and kill others.[167]TheNavajohave traditionally believed thatwitcheswould turn into wolves by donning wolf skins and would kill people and raid graveyards.[168]TheDena'inabelieved wolves were once men and viewed them as brothers.[159]

In fable and literature

Aesopfeatured wolves in several of hisfables,playing on the concerns of Ancient Greece's settled, sheep-herding world. His most famous is the fable of "The Boy Who Cried Wolf",which is directed at those who knowingly raise false alarms, and from which the idiomatic phrase" tocry wolf"is derived. Some of his other fables concentrate on maintaining the trust between shepherds and guard dogs in their vigilance against wolves, as well as anxieties over the close relationship between wolves and dogs. Although Aesop used wolves to warn, criticize and moralize about human behaviour, his portrayals added to the wolf's image as a deceitful and dangerous animal. TheBibleuses an image of a wolf lying with a lamb in a utopian vision of the future. In theNew Testament,Jesusis said to have used wolves as illustrations of the dangers his followers, whom he represents as sheep, would face should they follow him.[169]

Isengrim the wolf, a character first appearing in the 12th-century Latin poemYsengrimus,is a major character in theReynardCycle, where he stands for the low nobility, whilst his adversary, Reynard the fox, represents the peasant hero. Isengrim is forever the victim of Reynard's wit and cruelty, often dying at the end of each story.[170]The tale of "Little Red Riding Hood",first written in 1697 byCharles Perrault,is considered to have further contributed to the wolf's negative reputation in the Western world. TheBig Bad Wolfis portrayed as a villain capable of imitating human speech and disguising itself with human clothing. The character has been interpreted as an allegoricalsexual predator.[171]Villainous wolf characters also appear inThe Three Little Pigsand "The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats".[172]The hunting of wolves, and their attacks on humans and livestock, feature prominently inRussian literature,and are included in the works ofLeo Tolstoy,Anton Chekhov,Nikolay Nekrasov,Ivan Bunin,Leonid Pavlovich Sabaneyev,and others. Tolstoy'sWar and Peaceand Chekhov'sPeasantsboth feature scenes in which wolves are hunted with hounds andBorzois.[173]The musicalPeter and the Wolfinvolves a wolf being captured for eating a duck, but is spared and sent to a zoo.[174]

Wolves are among the central characters ofRudyard Kipling'sThe Jungle Book.His portrayal of wolves has been praised posthumously by wolf biologists for his depiction of them: rather than being villainous or gluttonous, as was common in wolf portrayals at the time of the book's publication, they are shown as living in amiable family groups and drawing on the experience of infirm but experienced elder pack members.[175]Farley Mowat's largely fictional 1963 memoirNever Cry Wolfis widely considered to be the most popular book on wolves, having been adapted into aHollywood filmand taught in several schools decades after its publication. Although credited with having changed popular perceptions on wolves by portraying them as loving, cooperative and noble, it has been criticized for its idealization of wolves and its factual inaccuracies.[176][177][178]

Conflicts

Human presence appears to stress wolves, as seen by increasedcortisollevels in instances such as snowmobiling near their territory.[179]

Predation on livestock

Livestock depredation has been one of the primary reasons for hunting wolves and can pose a severe problem for wolf conservation. As well as causing economic losses, the threat of wolf predation causes great stress on livestock producers, and no foolproof solution of preventing such attacks short of exterminating wolves has been found.[180]Some nations help offset economic losses to wolves through compensation programs or state insurance.[181]Domesticated animals are easy prey for wolves, as they have been bred under constant human protection, and are thus unable to defend themselves very well.[182]Wolves typically resort to attacking livestock when wild prey is depleted.[183]In Eurasia, a large part of the diet of some wolf populations consists of livestock, while such incidents are rare in North America, where healthy populations of wild prey have been largely restored.[180]

The majority of losses occur during the summer grazing period, untended livestock in remote pastures being the most vulnerable to wolf predation.[184]The most frequently targeted livestock species are sheep (Europe),domestic reindeer(northern Scandinavia),goats(India),horses(Mongolia),cattleandturkeys(North America).[180]The number of animals killed in single attacks varies according to species: most attacks on cattle and horses result in one death, while turkeys, sheep and domestic reindeer may be killed in surplus.[185]Wolves mainly attack livestock when the animals are grazing, though they occasionally break into fenced enclosures.[186]

Competition with dogs

A review of the studies on the competitive effects of dogs onsympatriccarnivores did not mention any research on competition between dogs and wolves.[187][188]Competition would favour the wolf, which is known to kill dogs; however, wolves usually live in pairs or in small packs in areas with high human persecution, giving them a disadvantage when facing large groups of dogs.[188][189]

Wolves kill dogs on occasion, and some wolf populations rely on dogs as an important food source. In Croatia, wolves kill more dogs than sheep, and wolves in Russia appear to limit stray dog populations. Wolves may display unusually bold behaviour when attacking dogs accompanied by people, sometimes ignoring nearby humans. Wolf attacks on dogs may occur both in house yards and in forests. Wolf attacks on hunting dogs are considered a major problem in Scandinavia and Wisconsin.[180][190]Although the number of dogs killed each year by wolves is relatively low, it induces a fear of wolves entering villages and farmyards to prey on them. In many cultures, dogs are seen as family members, or at least working team members, and losing one can lead to strong emotional responses such as demanding more liberal hunting regulations.[188]

Dogs that are employed to guard sheep help to mitigate human–wolf conflicts, and are often proposed as one of the non-lethal tools in the conservation of wolves.[188][191]Shepherd dogs are not particularly aggressive, but they can disrupt potential wolf predation by displaying what is to the wolf ambiguous behaviours, such as barking, social greeting, invitation to play or aggression. The historical use of shepherd dogs across Eurasia has been effective against wolf predation,[188][192]especially when confining sheep in the presence of several livestock guardian dogs.[188][193]Shepherd dogs are sometimes killed by wolves.[188]

Attacks on humans

The fear of wolves has been pervasive in many societies, though humans are not part of the wolf's natural prey.[194]How wolves react to humans depends largely on their prior experience with people: wolves lacking any negative experience of humans, or which are food-conditioned, may show little fear of people.[195]Although wolves may react aggressively when provoked, such attacks are mostly limited to quick bites on extremities, and the attacks are not pressed.[194]

Predatory attacks may be preceded by a long period ofhabituation,in which wolves gradually lose their fear of humans. The victims are repeatedly bitten on the head and face, and are then dragged off and consumed unless the wolves are driven off. Such attacks typically occur only locally and do not stop until the wolves involved are eliminated. Predatory attacks can occur at any time of the year, with a peak in the June–August period, when the chances of people entering forested areas (for livestockgrazingor berry and mushroom picking) increase.[194]Cases of non-rabid wolf attacks in winter have been recorded inBelarus,KirovandIrkutskoblasts,KareliaandUkraine.Also, wolves with pups experience greater food stresses during this period.[36]The majority of victims of predatory wolf attacks are children under the age of 18 and, in the rare cases where adults are killed, the victims are almost always women.[194]Indian wolves have a history of preying on children, a phenomenon called "child-lifting". They may be taken primarily in the spring and summer periods during the evening hours, and often within human settlements.[196]

Cases of rabid wolves are low when compared to other species, as wolves do not serve as primary reservoirs of the disease, but can be infected by animals such as dogs, jackals and foxes. Incidents of rabies in wolves are very rare in North America, though numerous in the easternMediterranean,theMiddle EastandCentral Asia.Wolves apparently develop the "furious" phase of rabies to a very high degree. This, coupled with their size and strength, makes rabid wolves perhaps the most dangerous of rabid animals.[194]Bites from rabid wolves are 15 times more dangerous than those of rabid dogs.[197]Rabid wolves usually act alone, travelling large distances and often biting large numbers of people and domestic animals. Most rabid wolf attacks occur in the spring and autumn periods. Unlike with predatory attacks, the victims of rabid wolves are not eaten, and the attacks generally occur only on a single day. The victims are chosen at random, though most cases involve adult men. During the fifty years up to 2002, there were eight fatal attacks in Europe and Russia, and more than two hundred in southern Asia.[194]

Human hunting of wolves

Theodore Rooseveltsaid wolves are difficult to hunt because of their elusiveness, sharp senses, high endurance, and ability to quickly incapacitate and kill hunting dogs.[198]Historic methods included killing of spring-born litters in their dens,coursingwith dogs (usually combinations ofsighthounds,BloodhoundsandFox Terriers), poisoning withstrychnine,andtrapping.[199][200]

A popular method of wolf hunting in Russia involves trapping a pack within a small area by encircling it withfladrypoles carrying a human scent. This method relies heavily on the wolf's fear of human scents, though it can lose its effectiveness when wolves become accustomed to the odor. Some hunters can lure wolves by imitating their calls. InKazakhstanandMongolia,wolves are traditionallyhunted usingeaglesand large falcons, though this practice is declining, as experienced falconers are becoming few in number. Shooting wolves from aircraft is highly effective, due to increased visibility and direct lines of fire.[200]Several types of dog, including theBorzoiandKyrgyz Tajgan,have been specifically bred for wolf hunting.[188]

As pets and working animals

Wolves andwolf-dog hybridsare sometimes kept asexotic pets.Although closely related to domestic dogs, wolves do not show the same tractability as dogs in living alongside humans, being generally less responsive to human commands and more likely to act aggressively. A person is more likely to be fatally mauled by a pet wolf or wolf-dog hybrid than by a dog.[201]

Notes

- ^Populations of Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Pakistan are included in Appendix I. Excludes domesticated form and dingo, which are referenced asCanus lupus familiarisandCanus lupus dingo.

- ^Domestic and feraldogsare included in thephylogeneticbut not colloquial definition of 'wolf', and thus not in the scope of this article.

References

- ^abcdeBoitani, L.; Phillips, M. & Jhala, Y. (2023) [amended version of 2018 assessment]."Canis lupus".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2023:e.T3746A247624660.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T3746A247624660.en.RetrievedJune 2,2024.

- ^"Appendices | CITES".cites.org.RetrievedJanuary 14,2022.

- ^abcLinnæus, Carl (1758)."Canis Lupus".Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I(in Latin) (10 ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 39–40.

- ^Harper, Douglas."wolf".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^A. Lehrman (1987). "Anatolian Cognates of the PIE Word for 'Wolf'".Die Sprache.33:13–18.

- ^Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944).The Wolves of North America, Part I.New York,Dover Publications,Inc. p. 390.

- ^Marvin 2012,pp. 74–75.

- ^Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o'Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015)."Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species".Current Biology.25(#16): 2158–65.Bibcode:2015CBio...25.2158K.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060.PMID26234211.

- ^Harper, Douglas."canine".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995)."2-Origins of the dog".In Serpell, James (ed.).The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People.Cambridge University Press. pp.7–20.ISBN0521415292.

- ^Wozencraft, W. C.(2005)."Order Carnivora".InWilson, D. E.;Reeder, D. M. (eds.).Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference(3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577.ISBN978-0-8018-8221-0.OCLC62265494.

- ^Larson, G.; Bradley, D. G. (2014)."How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics".PLOS Genetics.10(1): e1004093.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004093.PMC3894154.PMID24453989.

- ^Alvares, Francisco; Bogdanowicz, Wieslaw; Campbell, Liz A.D.; Godinho, Rachel; Hatlauf, Jennifer;Jhala, Yadvendradev V.;Kitchener, Andrew C.; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Krofel, Miha; Moehlman, Patricia D.; Senn, Helen; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Viranta, Suvi; Werhahn, Geraldine (2019)."Old World Canis spp. with taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations. CIBIO. Vairão, Portugal, 28–30 May 2019"(PDF).IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group.RetrievedMarch 6,2020.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 239–245.

- ^Iurino, Dawid A.; Mecozzi, Beniamino; Iannucci, Alessio; Moscarella, Alfio; Strani, Flavia; Bona, Fabio; Gaeta, Mario; Sardella, Raffaele (February 25, 2022)."A Middle Pleistocene wolf from central Italy provides insights on the first occurrence of Canis lupus in Europe".Scientific Reports.12(1): 2882.Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2882I.doi:10.1038/s41598-022-06812-5.ISSN2045-2322.PMC8881584.PMID35217686.

- ^Tedford, Richard H.; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl E. (2009). "Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)".Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.325:1–218.doi:10.1206/574.1.hdl:2246/5999.S2CID83594819.

- ^abcThalmann, Olaf; Perri, Angela R. (2018). "Paleogenomic Inferences of Dog Domestication". In Lindqvist, C.; Rajora, O. (eds.).Paleogenomics.Population Genomics. Springer, Cham. pp. 273–306.doi:10.1007/13836_2018_27.ISBN978-3-030-04752-8.

- ^Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; et al. (2014)."Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs".PLOS Genetics.10(1). e1004016.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016.PMC3894170.PMID24453982.

- ^Skoglund, Pontus; Ersmark, Erik; Palkopoulou, Eleftheria; Dalén, Love (2015)."Ancient Wolf Genome Reveals an Early Divergence of Domestic Dog Ancestors and Admixture into High-Latitude Breeds".Current Biology.25(11): 1515–1519.Bibcode:2015CBio...25.1515S.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019.PMID26004765.

- ^abcFan, Zhenxin; Silva, Pedro; Gronau, Ilan; Wang, Shuoguo; Armero, Aitor Serres; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ramirez, Oscar; Pollinger, John; Galaverni, Marco; Ortega Del-Vecchyo, Diego; Du, Lianming; Zhang, Wenping; Zhang, Zhihe; Xing, Jinchuan; Vilà, Carles; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Godinho, Raquel; Yue, Bisong; Wayne, Robert K. (2016)."Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves".Genome Research.26(2): 163–173.doi:10.1101/gr.197517.115.PMC4728369.PMID26680994.

- ^Hennelly, Lauren M.; Habib, Bilal; Modi, Shrushti; Rueness, Eli K.; Gaubert, Philippe; Sacks, Benjamin N. (2021). "Ancient divergence of Indian and Tibetan wolves revealed by recombination-aware phylogenomics".Molecular Ecology.30(24): 6687–6700.Bibcode:2021MolEc..30.6687H.doi:10.1111/mec.16127.PMID34398980.S2CID237147842.

- ^abBergström, Anders; Stanton, David W. G.; Taron, Ulrike H.; Frantz, Laurent; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ersmark, Erik; Pfrengle, Saskia; Cassatt-Johnstone, Molly; Lebrasseur, Ophélie; Girdland-Flink, Linus; Fernandes, Daniel M.; Ollivier, Morgane; Speidel, Leo; Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Westbury, Michael V. (July 14, 2022)."Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs".Nature.607(7918): 313–320.Bibcode:2022Natur.607..313B.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04824-9.ISSN0028-0836.PMC9279150.PMID35768506.

- ^abLoog, Liisa; Thalmann, Olaf; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Schuenemann, Verena J.; Perri, Angela; Germonpré, Mietje; Bocherens, Herve; Witt, Kelsey E.; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Velasco, Marcela S.; Lundstrøm, Inge K. C.; Wales, Nathan; Sonet, Gontran; Frantz, Laurent; Schroeder, Hannes (May 2020)."Ancient DNA suggests modern wolves trace their origin to a Late Pleistocene expansion from Beringia".Molecular Ecology.29(9): 1596–1610.Bibcode:2020MolEc..29.1596L.doi:10.1111/mec.15329.ISSN0962-1083.PMC7317801.PMID31840921.

- ^Freedman, Adam H; Wayne, Robert K (2017)."Deciphering the Origin of Dogs: From Fossils to Genomes".Annual Review of Animal Biosciences.5:281–307.doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937.PMID27912242.S2CID26721918.

- ^abGopalakrishnan, Shyam; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Niemann, Jonas; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Vieira, Filipe G.; Carøe, Christian; Montero, Marc de Manuel; Kuderna, Lukas; Serres, Aitor; González-Basallote, Víctor Manuel; Liu, Yan-Hu; Wang, Guo-Dong; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Mirarab, Siavash; Fernandes, Carlos; Gaubert, Philippe; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Budd, Jane; Rueness, Eli Knispel; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018)."Interspecific Gene Flow Shaped the Evolution of the Genus Canis".Current Biology.28(21): 3441–3449.e5.Bibcode:2018CBio...28E3441G.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.041.PMC6224481.PMID30344120.

- ^abSinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Gopalakrishan, Shyam; Vieira, Filipe G.; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Raundrup, Katrine; Heide Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Meldgaard, Morten; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Mikkelsen, Johan Brus; Marquard-Petersen, Ulf; Dietz, Rune; Sonne, Christian; Dalén, Love; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018)."Population genomics of grey wolves and wolf-like canids in North America".PLOS Genetics.14(11): e1007745.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007745.PMC6231604.PMID30419012.

- ^Wang, Guo-Dong; Zhang, Ming; Wang, Xuan; Yang, Melinda A.; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Lu, Heng; Feng, Xiaotian; Skoglund, Pontus; Wang, Lu; Fu, Qiaomei; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2019)."Genomic Approaches Reveal an Endemic Subpopulation of Gray Wolves in Southern China".iScience.20:110–118.Bibcode:2019iSci...20..110W.doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.008.PMC6817678.PMID31563851.

- ^Iacolina, Laura; Scandura, Massimo; Gazzola, Andrea; Cappai, Nadia; Capitani, Claudia; Mattioli, Luca; Vercillo, Francesca; Apollonio, Marco (2010). "Y-chromosome microsatellite variation in Italian wolves: A contribution to the study of wolf-dog hybridization patterns".Mammalian Biology—Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde.75(4): 341–347.Bibcode:2010MamBi..75..341I.doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2010.02.004.

- ^abKopaliani, N.; Shakarashvili, M.; Gurielidze, Z.; Qurkhuli, T.; Tarkhnishvili, D. (2014). "Gene Flow between Wolf and Shepherd Dog Populations in Georgia (Caucasus)".Journal of Heredity.105(3): 345–53.doi:10.1093/jhered/esu014.PMID24622972.

- ^Moura, A. E.; Tsingarska, E.; Dąbrowski, M. J.; Czarnomska, S. D.; Jędrzejewska, B. A.; Pilot, M. G. (2013)."Unregulated hunting and genetic recovery from a severe population decline: The cautionary case of Bulgarian wolves".Conservation Genetics.15(2): 405–417.doi:10.1007/s10592-013-0547-y.

- ^Bergström, Anders; Frantz, Laurent; Schmidt, Ryan; Ersmark, Erik; Lebrasseur, Ophelie; Girdland-Flink, Linus; Lin, Audrey T.; Storå, Jan; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Anthony, David; Antipina, Ekaterina; Amiri, Sarieh; Bar-Oz, Guy; Bazaliiskii, Vladimir I.; Bulatović, Jelena; Brown, Dorcas; Carmagnini, Alberto; Davy, Tom; Fedorov, Sergey; Fiore, Ivana; Fulton, Deirdre; Germonpré, Mietje; Haile, James; Irving-Pease, Evan K.; Jamieson, Alexandra; Janssens, Luc; Kirillova, Irina; Horwitz, Liora Kolska; Kuzmanovic-Cvetković, Julka; Kuzmin, Yaroslav; Losey, Robert J.; Dizdar, Daria Ložnjak; Mashkour, Marjan; Novak, Mario; Onar, Vedat; Orton, David; Pasaric, Maja; Radivojevic, Miljana; Rajkovic, Dragana; Roberts, Benjamin; Ryan, Hannah; Sablin, Mikhail; Shidlovskiy, Fedor; Stojanovic, Ivana; Tagliacozzo, Antonio; Trantalidou, Katerina; Ullén, Inga; Villaluenga, Aritza; Wapnish, Paula; Dobney, Keith; Götherström, Anders; Linderholm, Anna; Dalén, Love; Pinhasi, Ron; Larson, Greger; Skoglund, Pontus (2020)."Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs".Science.370(6516): 557–564.doi:10.1126/science.aba9572.PMC7116352.PMID33122379.S2CID225956269.

- ^abMech, L. David (1974)."Canis lupus".Mammalian Species(37): 1–6.doi:10.2307/3503924.JSTOR3503924.Archivedfrom the original on July 31, 2019.RetrievedJuly 30,2019.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 129–132.

- ^abHeptner & Naumov 1998,p. 166.

- ^Mech 1981,p. 13.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqHeptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 164–270.

- ^Mech 1981,p. 14.

- ^Therrien, F. O. (2005). "Mandibular force profiles of extant carnivorans and implications for the feeding behaviour of extinct predators".Journal of Zoology.267(3): 249–270.doi:10.1017/S0952836905007430.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 112.

- ^abcdefghPaquet, P.; Carbyn, L. W. (2003)."Ch23: Gray wolfCanis lupusand allies ".In Feldhamer, G. A.; Thompson, B. C.; Chapman, J. A. (eds.).Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation(2 ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 482–510.ISBN0-8018-7416-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^abLopez 1978,p. 23.

- ^abHeptner & Naumov 1998,p. 174.

- ^abMiklosi, A. (2015)."Ch. 5.5.2—Wolves".Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition(2 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 110–112.ISBN978-0-19-104572-1.

- ^Macdonald, D. W.;Norris, S. (2001).Encyclopedia of Mammals.Oxford University Press. p. 45.ISBN978-0-7607-1969-5.

- ^abcLopez 1978,p. 19.

- ^Lopez 1978,p. 18.

- ^Lopez 1978,pp. 19–20.

- ^abGipson, Philip S.; Bangs, Edward E.; Bailey, Theodore N.; Boyd, Diane K.; Cluff, H. Dean; Smith, Douglas W.; Jiminez, Michael D. (2002). "Color Patterns among Wolves in Western North America".Wildlife Society Bulletin.30(3): 821–830.JSTOR3784236.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 168–169.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,p. 168.

- ^Lopez 1978,p. 22.

- ^Anderson, T. M.; Vonholdt, B. M.; Candille, S. I.; Musiani, M.; Greco, C.; Stahler, D. R.; Smith, D. W.; Padhukasahasram, B.; Randi, E.; Leonard, J. A.; Bustamante, C. D.; Ostrander, E. A.; Tang, H.; Wayne, R. K.; Barsh, G. S. (2009)."Molecular and Evolutionary History of Melanism in North American Gray Wolves".Science.323(5919): 1339–1343.Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1339A.doi:10.1126/science.1165448.PMC2903542.PMID19197024.

- ^Hedrick, P. W. (2009)."Wolf of a different colour".Heredity.103(6): 435–436.doi:10.1038/hdy.2009.77.PMID19603061.S2CID5228987.

- ^Earle, M (1987). "A flexible body mass in social carnivores".American Naturalist.129(5): 755–760.doi:10.1086/284670.S2CID85236511.

- ^Sorkin, Boris (2008). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators".Lethaia.41(4): 333–347.Bibcode:2008Letha..41..333S.doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- ^Mech, L. David (1966).The Wolves of Isle Royale.Fauna Series 7. Fauna of the National Parks of the United States. pp. 75–76.ISBN978-1-4102-0249-9.

- ^abNewsome, Thomas M.; Boitani, Luigi; Chapron, Guillaume; Ciucci, Paolo; Dickman, Christopher R.; Dellinger, Justin A.; López-Bao, José V.; Peterson, Rolf O.; Shores, Carolyn R.; Wirsing, Aaron J.; Ripple, William J. (2016)."Food habits of the world's grey wolves".Mammal Review.46(4): 255–269.doi:10.1111/mam.12067.hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30085823.S2CID31174275.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,p. 107.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 109–110.

- ^Landry, Zoe; Kim, Sora; Trayler, Robin B.; Gilbert, Marisa; Zazula, Grant; Southon, John; Fraser, Danielle (June 1, 2021)."Dietary reconstruction and evidence of prey shifting in Pleistocene and recent gray wolves (Canis lupus) from Yukon Territory".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.571:110368.Bibcode:2021PPP...57110368L.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110368.RetrievedApril 23,2024– via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^Mech 1981,p. 172.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,p. 201.

- ^abcdHeptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 213–231.

- ^Gable, T. D.; Windels, S. K.; Homkes, A. T. (2018). "Do wolves hunt freshwater fish in spring as a food source?".Mammalian Biology.91:30–33.Bibcode:2018MamBi..91...30G.doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2018.03.007.S2CID91073874.

- ^Woodford, Riley (November 2004)."Alaska's Salmon-Eating Wolves".Wildlifenews.alaska.gov.RetrievedJuly 25,2019.

- ^McAllister, I. (2007).The Last Wild Wolves: Ghosts of the Rain Forest.University of California Press. p. 144.ISBN978-0520254732.

- ^Fuller, T. K. (2019)."Ch3-What wolves eat".Wolves: Spirit of the Wild.Chartwell Crestline. p. 53.ISBN978-0785837381.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 109.

- ^Mech 1981,p. 180.

- ^Klein, D. R. (1995). "The introduction, increase, and demise of wolves on Coronation Island, Alaska". InCarbyn, L. N.;Fritts, S. H.; Seip, D. R. (eds.).Ecology and conservation of wolves in a changing world.Canadian Circumpolar Institute, Occasional Publication No. 35. pp. 275–280.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 266–268.

- ^Merrit, Dixon (January 7, 1921)."World's Greatest Animal Dead"(PDF).US Department of Agriculture Division of Publications. p. 2.Archived(PDF)from the original on July 24, 2019.RetrievedJuly 26,2019.

- ^Giannatos, G. (April 2004)."Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal Canis aureus L. in Greece"(PDF).World Wildlife Fund Greece. pp. 1–47.Archived(PDF)from the original on December 9, 2017.RetrievedOctober 29,2019.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 269.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 261–263.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 263–264.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 266.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,p. 265.

- ^Sunquist, Melvin E.; Sunquist, Fiona (2002).Wild cats of the world.University of Chicago Press. p.167.ISBN0-226-77999-8.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 264–265.

- ^Jimenez, Michael D.; Asher, Valpa J.; Bergman, Carita; Bangs, Edward E.; Woodruff, Susannah P. (2008)."Gray Wolves,Canis lupus,Killed by Cougars,Puma concolor,and a Grizzly Bear,Ursus arctos,in Montana, Alberta, and Wyoming ".The Canadian Field-Naturalist.122:76.doi:10.22621/cfn.v122i1.550.

- ^Elbroch, L. M.; Lendrum, P. E.; Newsby, J.; Quigley, H.; Thompson, D. J. (2015)."Recolonizing wolves influence the realized niche of resident cougars".Zoological Studies.54(41): e41.doi:10.1186/s40555-015-0122-y.PMC6661435.PMID31966128.

- ^Miquelle, D. G.; Stephens, P. A.; Smirnov, E. N.; Goodrich, J. M.; Zaumyslova, O. J.; Myslenkov, A. E. (2005). "Tigers and Wolves in the Russian Far East: Competitive Exclusion, Functional Redundancy and Conservation Implications". In Ray, J. C.; Berger, J.; Redford, K. H.; Steneck, R. (eds.).Large Carnivores and the Conservation of Biodiversity.Island Press. pp. 179–207.ISBN1-55963-080-9.Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2016.RetrievedNovember 22,2015.

- ^Monchot, H.; Mashkour, H. (2010)."Hyenas around the cities. The case of Kaftarkhoun (Kashan- Iran)".Journal of Taphonomy.8(1): 17–32..

- ^Mills, M. G. L.; Mills, Gus; Hofer, Heribert (1998).Hyaenas: status survey and conservation action plan.IUCN. pp. 24–25.ISBN978-2-8317-0442-5.Archivedfrom the original on May 16, 2016.RetrievedNovember 22,2015.

- ^Nayak, S.; Shah, S.; Borah, J. (2015). "Going for the kill: an observation of wolf-hyaena interaction in Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary, Rajasthan, India".Canid Biology & Conservation.18(7): 27–29.

- ^Dinets, Vladimir; Eligulashvili, Beniamin (2016). "Striped Hyaenas (Hyaena hyaena) in Grey Wolf (Canis lupus) packs: Cooperation, commensalism or singular aberration?".Zoology in the Middle East.62:85–87.doi:10.1080/09397140.2016.1144292.S2CID85957777.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 208–211.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 211–213.

- ^Graves 2007,pp. 77–85.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 202–208.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 164.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 2–3, 28.

- ^Molnar, B.; Fattebert, J.; Palme, R.; Ciucci, P.; Betschart, B.; Smith, D. W.; Diehl, P. (2015)."Environmental and intrinsic correlates of stress in free-ranging wolves".PLOS ONE.10(9). e0137378.Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1037378M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137378.PMC4580640.PMID26398784.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 1–2.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 12–13.

- ^Nowak, R. M.; Paradiso, J. L. (1983)."Carnivora;Canidae".Walker's Mammals of the World.Vol. 2 (4th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p.953.ISBN9780801825255.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 38.

- ^abJędrzejewski, W. O.; Schmidt, K.; Theuerkauf, J. R.; Jędrzejewska, B. A.; Kowalczyk, R. (2007). "Territory size of wolvesCanis lupus:Linking local (Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland) and Holarctic-scale patterns ".Ecography.30(1): 66–76.Bibcode:2007Ecogr..30...66J.doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.04826.x.S2CID62800394.

- ^abcMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 19–26.

- ^Mech, L. D. (1977)."Wolf-Pack Buffer Zones as Prey Reservoirs".Science.198(4314): 320–321.Bibcode:1977Sci...198..320M.doi:10.1126/science.198.4314.320.PMID17770508.S2CID22125487.Archivedfrom the original on July 24, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 10,2019.

- ^Mech, L. David; Adams, L. G.; Meier, T. J.; Burch, J. W.; Dale, B. W. (2003)."Ch.8-The Denali Wolf-Prey System".The Wolves of Denali.University of Minnesota Press. p. 163.ISBN0-8166-2959-5.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 66–103.

- ^Busch 2007,p. 59.

- ^Lopez 1978,p. 38.

- ^Lopez 1978,pp. 39–41.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 90.

- ^Peters, R. P.; Mech, L. D. (1975). "Scent-marking in wolves".American Scientist.63(6): 628–637.Bibcode:1975AmSci..63..628P.PMID1200478.

- ^abcHeptner & Naumov 1998,p. 248.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 5.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 175.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 234–238.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 42–46.

- ^abHeptner & Naumov 1998,pp. 249–254.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 47.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 46–49.

- ^Fox, M. W. (1978).The Dog: Its Domestication and Behavior.Garland STPM. p. 33.ISBN978-0894642029.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 119–121.

- ^Thurber, J. M.; Peterson, R. O. (1993). "Effects of Population Density and Pack Size on the Foraging Ecology of Gray Wolves".Journal of Mammalogy.74(4): 879–889.doi:10.2307/1382426.JSTOR1382426.S2CID52063038.

- ^Mech, Smith & MacNulty 2015,p. 4.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,p. 233.

- ^Heptner & Naumov 1998,p. 240.

- ^MacNulty, Daniel; Mech, L. David; Smith, Douglas W. (2007)."A proposed ethogram of large-carnivore predatory behavior, exemplified by the wolf".Journal of Mammalogy.88(3): 595–605.doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-119R1.1.

- ^abMech, Smith & MacNulty 2015,pp. 1–3.

- ^Mech, Smith & MacNulty 2015,p. 7.

- ^Mech, Smith & MacNulty 2015,p. 82–89.

- ^Zimen, Erik (1981).The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World.Souvenir Press.pp. 217–218.ISBN978-0-285-62411-5.

- ^Mech 1981,p. 185.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 58.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 122–125.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 230.

- ^abMech & Boitani 2003,pp. 321–324.

- ^Government of Canada (July 29, 2019)."Schedule 3 (section 26) Protected Species".Justice Laws Website.Archivedfrom the original on April 9, 2019.RetrievedOctober 30,2019.

- ^State of Alaska (October 29, 2019)."Wolf Hunting in Alaska".Alaska Department of Fish and Game.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2019.RetrievedOctober 30,2019.

- ^"Wolf Recovery under the Endangered Species Act"(PDF).US Fish and Wildlife Service. February 2007.Archived(PDF)from the original on August 3, 2019.RetrievedSeptember 1,2019.

- ^"Wolf Numbers in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan (excluding Isle Royale)—1976 to 2015".U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.RetrievedMarch 23,2020.

- ^"How many wild wolves are in the United States?".Wolf Conservation Center.RetrievedMay 10,2023.

- ^Nie, M. A. (2003).Beyond Wolves: The Politics of Wolf Recovery and Management.University of Minnesota Press. pp.118–119.ISBN0816639787.

- ^"Mexican Wolf Population Grows for Eighth Consecutive Year | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service".fws.gov.March 5, 2024.RetrievedMarch 6,2024.

- ^ab"Status of large carnivore populations in Europe 2012–2016".European Commission.Archivedfrom the original on September 2, 2019.RetrievedSeptember 2,2019.

- ^European Commission:Status, management and distribution of large carnivores—bear, lynx, wolf & wolverine—in Europe December 2012.page 50.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 318–320.

- ^The Wolf Dilemma: Following the Practices of Several Actors in Swedish Large Carnivore Management.Ramsey, Morag (2015)https:// diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:821120/FULLTEXT01.pdfRetrieved 30 September 2023

- ^Goldthorpe, Gareth (2016).The wolf in Eurasia—a regional approach to the conservation and management of a top-predator in Central Asia and the South Caucasus.Fauna & Flora International.doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.10128.20480.

- ^Baskin, Leonid (2016)."Hunting as Sustainable Wildlife Management".Mammal Study.41(4): 173–180.doi:10.3106/041.041.0402.

- ^"The Wolf in Russia—situations and problems"(PDF).Wolves and Humans Foundation. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 23, 2007.RetrievedSeptember 2,2019.

- ^abFisher, A. (January 29, 2019)."Conservation in conflict: Advancement and the Arabian wolf".Middle East Eye.Archivedfrom the original on November 7, 2019.RetrievedNovember 11,2019.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,pp. 323, 327.

- ^Busch 2007,p. 231.

- ^Şekercioğlu, Çağan (December 15, 2013)."Turkey's Wolves Are Texting Their Travels to Scientists".National Geographic.Archivedfrom the original on October 6, 2019.RetrievedNovember 19,2019.

- ^Mech & Boitani 2003,p. 327.