Written Chinese

| Written Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Tiếng Trung | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōngwén | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Chinese writing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Han writing[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Hán văn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Hán văn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hànwén | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han writing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Written Chineseis awriting systemthat usesChinese charactersand other symbols to represent theChinese languages.Chinese characters do not directly represent pronunciation, unlike letters in anAlpha betor syllabograms in asyllabary.Rather, the writing system ismorphosyllabic:characters are one spokensyllablein length, but generally correspond tomorphemesin the language, which may either be independent words, or part of a polysyllabic word. Most characters are constructed from smaller components that may reflect the character's meaning or pronunciation.[1]Literacy requires the memorization of thousands of characters; college-educated Chinese speakers know approximately 4,000.[2][3]This has led in part to the adoption of complementary transliteration systems as a means of representing the pronunciation of Chinese.[4]

Chinese writing is first attested during the lateShang dynasty(c. 1250– c. 1050 BCE),[5][6][7]but the process of creating characters is thought to have begun centuries earlier during the Late Neolithic and early Bronze Age (c. 2500–2000 BCE).[8]After a period of variation and evolution, Chinese characters were standardized under theQin dynasty(221–206 BCE).[9]Over the millennia, these characters have evolved into well-developed styles ofChinese calligraphy.[10]As thevarieties of Chinesediverged, a situation ofdiglossiadeveloped, with speakers of mutually unintelligible varieties able to communicate through writing usingLiterary Chinese.[11]In the early 20th century, Literary Chinese was replaced in large part withwritten vernacular Chinese,largely corresponding toStandard Chinese,a form based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin. Although most othervarieties of Chineseare not written, there are traditions ofwritten Cantonese,written Shanghaineseandwritten Hokkien,among others.

Structure

[edit]

Written Chinese is not based on an Alpha bet or syllabary.[12]Most characters can be analyzed as compounds of smaller components, which may be assembled according to several different principles. Characters and components may reflect aspects of meaning or pronunciation. The best known exposition of Chinese character composition is theShuowen Jiezi,compiled byXu Shenc. 100 CE.Xu did not have access to the earliest forms of Chinese characters, and his analysis is not considered to fully capture the nature of the writing system.[13]Nevertheless, no later work has supplanted theShuowen Jieziin terms of breadth, and it is still relevant to etymological research today.[14]

Derivation of characters

[edit]According to theShuowen Jiezi,Chinese characters are developed on six basic principles.[15](These principles, though popularized by theShuowen Jiezi,were developed earlier; the oldest known mention of them is in theRites of Zhou,a text fromc. 150 BCE.[16]) The first two principles produce simple characters, known asVăn(wén):[15]

- Pictographs(Tượng hình;xiàngxíng): in which the character is a graphical depiction of the object it denotes.

- Examples:Người(rén;'person'),Ngày(rì;'sun'),Mộc(mù;'tree').

- Indicatives(Chỉ sự;zhǐshì): in which the character represents an abstract notion.

- Examples:Thượng(shàng;'up'),Hạ(xià;'down'),Tam(sān;'three').

The remaining four principles produce complex characters historically calledTự(zì), though this term is now generally used to refer to all characters, whether simple or complex. Of these four, two construct characters from simpler parts:[15]

- Ideographic compounds(Hiểu ý;Hiểu ý;huìyì): in which two or more parts are used for their meaning. This yields a composite meaning, which is then applied to the new character.

- Example:Đông;Đông(dōng;'east'), which represents a sun rising in the trees.

- Phono-semantic compounds(Hình thanh;Hình thanh;xíngshēng): in which one part—often called theradical—indicates the general semantic category of the character, such as being related towateroreyes', with the other part being another character used for its phonetic value.

- Example:Tình(qíng;'clear weather'), which is composed ofNgày(rì;'sun'), andThanh(qīng;'grue'), which is used for its pronunciation.

The last two principles do not produce new written forms; they instead transfer new meanings to existing forms:[15]

- Transference(Chuyển chú;Chuyển chú;zhuǎnzhù): in which a character, often with a simple, concrete meaning takes on an extended, more abstract meaning.

- Example:Võng;wǎng,which was originally a pictograph depicting a fishing net. Over time, it has taken on an extended meaning, covering any kind oflattice:for instance, it is the word used to refer to computer networks.

- Loangraphs(Giả tá;jiǎjiè): in which a character is used, either intentionally or accidentally, for some entirely different purpose.

- Example:Ca(gē;'elder brother') is not attested in formal writing prior to the Tang dynasty, and was created from the leftmost component of the more ancient characterCa(gē;'to sing'). The ancient characterHuynh(xiōng) meaning 'elder brother' continues to be used in idioms and formal writing, whereasCais used in daily conversation in most Chinese dialects. Some dialects such as Minnan which retain features of spoken Old Chinese continue to useHuynhexclusively for 'elder brother' in daily conversation.

In contrast to the popular conception of written Chinese asideographic,the vast majority of characters—about 95% of those in theShuowen Jiezi—either reflect elements of pronunciation, or are logical aggregates.[1]In fact, some phonetic complexes were originally simple pictographs that were later augmented by the addition of a semantic root. An example isChú;zhù;'lampwick', now archaic, which was originally a pictograph of a lamp standChủ,a character that is now pronouncedzhǔand means 'host', or the characterHỏa(huǒ;'fire') was added to indicate that the meaning is fire related.[17]

Chinese characters are written to fit into a square, even when composed of two simpler forms written side-by-side or top-to-bottom. In such cases, each form is compressed to fit the entire character into a square.[18]

Strokes

[edit]Character components can be further subdivided into individual written strokes. The strokes of Chinese characters fall into eight main categories: "horizontal"⟨Một⟩,"vertical"⟨丨⟩,"left-falling"⟨Phiệt⟩,"right-falling"⟨,⟩,"rising", "dot"⟨,⟩,"hook"⟨Quyết⟩,and "turning"⟨乛⟩,⟨乚⟩,⟨Ất⟩.[19]

There are eight basic rules of stroke order in writing a Chinese character, which apply only generally and are sometimes violated:[20]

- Horizontal strokes are written before vertical ones.

- Left-falling strokes are written before right-falling ones.

- Characters are written from top to bottom.

- Characters are written from left to right.

- If a character is framed from above, the frame is written first.

- If a character is framed from below, the frame is written last.

- Frames are closed last.

- In a symmetrical character, the middle is drawn first, then the sides.

Layout

[edit]

As characters are essentially rectilinear and are not joined with one another, written Chinese does not require a set orientation. Chinese texts were traditionally written in columns from top to bottom, which were laid out from right to left. Prior to the 20th century, Literary Chinese used little to no punctuation, with the breaks between sentences and phrases determined largely by context and the rhythms implied by patterns of syllables.[21]

In the 20th century, the layout used in Western scripts—where text is written in rows from left to right, which are laid out from top to bottom—became predominant in mainland China, where it was mandated by the Chinese government in 1955. Vertical layouts are still used for aesthetic effect, or when space limitations require it, such as on signage or book spines.[22]The government ofTaiwanfollowed suit in 2004 for official documents, but vertical layouts have persisted in some books and newspapers.[23]

Less frequently, Chinese is written in rows from right to left, usually on signage or banners, though a left to right orientation remains more common.[24]

The use of punctuation has also become more common. In general, punctuation occupies the width of a full character, such that text remains visually well-aligned in a grid. Punctuation used in simplified Chinese shows clear influence from that used in Western scripts, though some marks are particular to Asian languages. For example, there are double and single quotation marks (『 』 and “” ), and a hollow full stop (. ), which is used to separate sentences in an identical manner to a Western full stop. A special mark called anenumeration comma(, ) is used to separate items in a list, as opposed to the clauses in a sentence.

History

[edit]

Written Chinese is one of the oldest continuously used writing systems.[25]The earliest examples universally accepted as Chinese writing are theoracle bone inscriptionsmade during the reign of theShangkingWu Ding(c. 1250– c. 1192 BCE). These inscriptions were made primarily on ox scapulae and turtle shells in order to record the results of divinations conducted by the Shang royal family. Characters posing a question were first carved into the bones. The question's answer was then divined by heating the bones over a fire and interpreting the resulting cracks that formed. The interpretation was then carved into the sameoracle bone.[26]

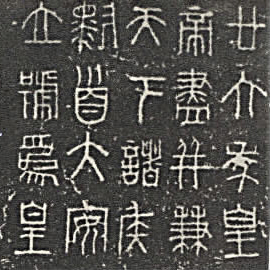

In 2003, 11 isolated symbols carved on tortoise shells were found at theJiahuarchaeological site inHenan—with some bearing a striking resemblance to certain modern characters, such asMục(mù;'eye'). The Jiahu site dates fromc. 6600 BCE,predating the earliest attested Chinese writing by more than 5,000 years. Garman Harbottle, who had headed a team of archaeologists at theUniversity of Science and Technology of Chinain Anhui—has suggested that these symbols were precursors to Chinese writing. However, the palaeographerDavid Keightleyargues instead that the time gap is too great to establish any connection.[27] From theLate Shangperiod (c. 1250– c. 1050 BCE), Chinese writing evolved into the form found incast inscriptionson ritual bronzes made during theWestern Zhoudynasty (c. 1046– 771 BCE) and theSpring and Autumn period(771–476 BCE), a form of writing called bronze script (Kim văn;jīnwén). Bronze script characters are less angular than their oracle bone script counterparts. The script became increasingly regularized during theWarring States period(475–221 BCE), settling into what is called 'script of the six states' (Lục quốc văn tự;liùguó wénzì), that Xu Shen used as source material in theShuowen Jiezi.These characters were later embellished and stylized to yield theseal script,which represents the oldest form of Chinese characters still in modern use. They are used principally forsignature seals,or chops, which are often used in place of a signature for Chinese documents and artwork.Li Sipromulgated the seal script as the standard throughout China, which had been recently united under the imperialQin dynasty(221–206 BCE).[9]

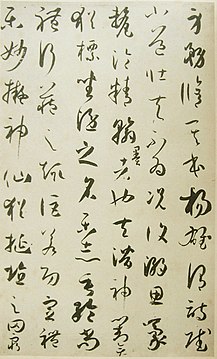

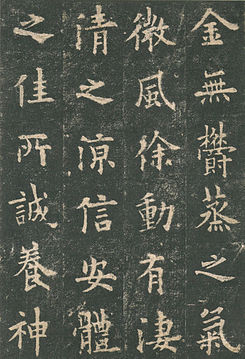

The initial adaptation of seal intoclerical scriptcan be attributed to scribes in thestate of Qinworking prior to the wars of unification. Clerical script forms generally have a "flat" appearance, being wider than their seal script equivalents.[28]In thesemi-cursive scriptthat evolved from clerical script, character elements begin to run into each other, though the characters themselves generally remain discrete. This is contrasted with fullycursive script,where characters are often rendered unrecognizable by their canonical forms.[29]Regular scriptis the most widely recognized script, and was considerably influenced by semi-cursive. In regular script, each stroke of each character is clearly drawn out from the others.[30]

Regular script is considered the archetypal Chinese writing and forms the basis for most printed forms. In addition, regular scriptimposes a stroke order,which must be followed in order for the characters to be written correctly.[31]Strictly speaking, this stroke order applies to the clerical, running, and grass scripts as well, but especially in the running and grass scripts, this order is occasionally deviated from. Thus, for instance, the characterMộc(mù;'wood') must be written starting with the horizontal stroke, drawn from left to right; next, the vertical stroke, from top to bottom; next, the left diagonal stroke, from top to bottom; and lastly the right diagonal stroke, from top to bottom.[32]

Simplification and standardization

[edit]Beginning in the mid-20th century, Chinese has primarily been written using eithersimplifiedortraditional characterforms. Simplified characters, which merge some character forms and reduce the average stroke count per character, were developed by the Chinese government with the stated goal of increasing literacy among the population. During this time, literacy rates did increase rapidly, but some observers instead attribute this to other education reforms and a general increase in the standard of living. Little systematic research has been conducted to support the conclusion that the use of simplified characters has affected literacy rates; studies conducted in China have instead focused on arbitrary statistics, such as quantifying the number of strokes saved on average in a given text sample.[33]Simplified characters are standard in mainland China,SingaporeandMalaysia,while traditional characters are standard inHong Kong,Macau,Taiwanand someoverseas Chinesecommunities.[34][page needed]

Simplified forms have also been characterized as being inconsistent. For instance, the traditionalLàm;ràn;'allow' is simplified toLàm,in which the phonetic on the right side is reduced from 17 strokes to 3, and the⾔ 'SPEECH'radical on the left also being simplified. However, the same phonetic component is not reduced in simplified characters such asNhưỡng;rǎng;'soil' andNãng;nàng;'snuffle'—these characters are relatively uncommon, and would therefore represent a negligible stroke reduction.[35]Other simplified forms derive from long-standing calligraphic abbreviations, as withVạn;wàn;'ten thousand', which has the traditional form ofVạn.[36]

Function

[edit]

Chinese characters have always been used to represent individual spoken syllables. While writing was being invented in the Yellow River valley, words in spoken Chinese were largely monosyllabic, and each written character corresponded to a monosyllabic word.[38]Spoken Chinese varieties have since acquired much more polysyllabic vocabulary,[39]usually compound words composed of morphemes corresponding to older monosyllabic words[40]

For over two thousand years, the predominant form of written Chinese wasLiterary Chinese,which had vocabulary and syntax rooted in the language of theChinese classics,as spoken around the time ofConfucius(c. 500 BCE). Over time, Literary Chinese acquired some elements of grammar and vocabulary from various varieties of vernacular Chinese that had since diverged. By the 20th century, Literary Chinese was distinctly different from any spoken vernacular, and had to be learned separately.[41][42]Once learned, it was a common medium for communication between people speaking different dialects, many of which were mutually unintelligible by the end of the first millennium CE.[43][11]

Varieties of Chinese vary in pronunciation, and to a lesser extent in vocabulary and grammar.[44]Modern written Chinese, which replaced Classical Chinese as the written standard as an indirect result of the 1919May Fourth Movement,is not technically bound to any single variety; however, it most nearly represents the vocabulary and syntax of Mandarin, by far the most widespread Chinese dialectal family in terms of both geographical area and number of speakers.[45]This form is known aswritten vernacular Chinese.[46]While some written vernacular Chinese expressions are often ungrammatical or unidiomatic outside of Mandarin, its use permits some communication between speakers of different dialects. This function may be considered analogous to that oflinguae francae,such asLatin.For literate speakers, it serves as a common medium; however, the forms of individual characters generally provide little insight to their meaning if not already known.[47]Ghil'ad Zuckermann's exploration ofphono-semantic matchinginStandard Chineseconcludes that the Chinese writing system is multifunctional, conveying both semantic and phonetic content.[48]

The variation in vocabulary among varieties has also led to informal use of "dialectal characters", which may include characters previously used in Literary Chinese that are considered archaic in written Standard Chinese.[49]Cantonese is unique among non-Mandarin regional languages in having a written colloquial standard, used in Hong Kong and overseas, with a large number of unofficial characters for words particular to this language.[50]Written Cantonesehas become quite popular on the Internet, while Standard Chinese is still normally used in formal written communications.[51]To a lesser degree,Hokkienis used similarly in Taiwan and elsewhere, though it lacks the level of standardization seen in Cantonese. However, Taiwan's Ministry of Education has promulgated a standard character set for Hokkien, which is taught in schools and encouraged for use by the general population.[52]

Media

[edit]Over the history of written Chinese, a variety of media have been used for writing. They include:

- Bamboo and wooden slips,from at least the 13th century BCE

- Paper,invented no later than the 2nd century BCE

- Silk,since at least the Han dynasty

- Stone, metal, wood, bamboo, plastic and ivory onseals.

Since at least the Han dynasty, such media have been used to createhanging scrollsandhandscrolls.

Literacy

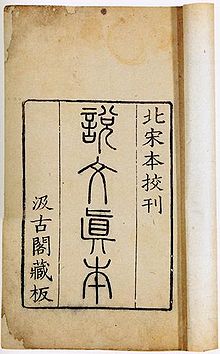

[edit]Because the majority of modern Chinese words contain more than one character, there are at least two measuring sticks for Chinese literacy: the number of characters known, and the number of words known.John DeFrancis,in the introduction to hisAdvanced Chinese Reader,estimates that a typical Chinese college graduate recognizes 4,000 to 5,000 characters, and 40,000 to 60,000 words.[2]Jerry Norman,inChinese,places the number of characters somewhat lower, at 3,000 to 4,000.[3]These counts are complicated by the tangled development of Chinese characters. In many cases, a single character came to have multiplevariants.This development was restrained to an extent by the standardization of the seal script during the Qin dynasty, but soon started again. Although theShuowen Jiezilists 10,516 characters—9,353 of them unique (some of which may already have been out of use by the time it was compiled) plus 1,163 graphic variants—theJiyunof the NorthernSong dynasty,compiled less than a thousand years later in 1039, contains 53,525 characters, most of them graphic variants.[53]

Dictionaries

[edit]Written Chinese is not based on an Alpha bet or syllabary, so Chinese dictionaries, as well as dictionaries that define Chinese characters in other languages, cannot easily be Alpha betized or otherwise lexically ordered, as English dictionaries are. The need to arrange Chinese characters in order to permit efficient lookup has given rise to a considerable variety of ways to organize and index the characters.[54]

A traditional mechanism is the method of radicals, which uses a set of character roots. These roots, or radicals, generally but imperfectly align with the parts used to compose characters by means of logical aggregation and phonetic complex. Acanonicalset of 214 radicals was developed during the rule of theKangxi Emperor(around the year 1700); these are sometimes called the Kangxi radicals. The radicals are ordered first by stroke count (that is, the number of strokes required to write the radical); within a given stroke count, the radicals also have a prescribed order.[55]

Every Chinese character falls (sometimes arbitrarily or incorrectly) under the heading of exactly one of these 214 radicals.[54]In many cases, the radicals are themselves characters, which naturally come first under their own heading. All other characters under a given radical are ordered by the stroke count of the character. Usually, however, there are still many characters with a given stroke count under a given radical. At this point, characters are not given in any recognizable order; the user must locate the character by going through all the characters with that stroke count, typically listed for convenience at the top of the page on which they occur.[56]

Because the method of radicals is applied only to the written character, one need not know how to pronounce a character before looking it up; the entry, once located, usually gives the pronunciation. However, it is not always easy to identify which of the various roots of a character is the proper radical. Accordingly, dictionaries often include a list of hard to locate characters, indexed by total stroke count, near the beginning of the dictionary. Some dictionaries include almost one-seventh of all characters in this list.[54]Alternatively, some dictionaries list "difficult" characters under more than one radical, with all but one of those entries redirecting the reader to the "canonical" location of the character according to Kangxi.

Other methods of organization exist, often in an attempt to address the shortcomings of the radical method, but are less common. For instance, it is common for a dictionary ordered principally by the Kangxi radicals to have an auxiliary index by pronunciation, expressed typically in eitherpinyinorbopomofo.[57]This index points to the page in the main dictionary where the desired character can be found. Other methods use only the structure of the characters, such as thefour-corner method,in which characters are indexed according to the kinds of strokes located nearest the four corners (hence the name of the method),[58]or theCangjie method,in which characters are broken down into a set of 24 basic components.[59]Neither the four-corner method nor the Cangjie method requires the user to identify the proper radical, although many strokes or components have alternate forms, which must be memorized in order to use these methods effectively.

The availability of computerized Chinese dictionaries now makes it possible to look characters up by any of the inde xing schemes described, thereby shortening the search process.

Transliteration

[edit]Chinese characters do not reliably indicate their pronunciation. Therefore, many transliteration systems have been developed to write the sounds of different varieties of Chinese. While many use theLatin Alpha bet,systems using theCyrillicandPerso-Arabic Alpha betshave also been designed. Among other purposes, these systems are used by students learning the corresponding varieties. The replacement of Chinese characters with a phonetic writing system was first prominently proposed during the May Fourth Movement, partly motivated by a desire to increase the country's literacy rate. The idea gained further support following the victory of the Communists in 1949, who immediately began two parallel programs regarding written Chinese. The first was the development of an Alpha bet to write the sounds of Mandarin, the variety spoken by around two-thirds of the Chinese population.[44]The other program investigated the simplification of the standard character forms. Initially, character simplification was not competing with the idea of a phonetic script; rather, simplification was intended to make the transition to a fully phonetic writing system easier.[4]

By 1958, official priorities had shifted towards character simplification. TheHanyu Pinyin(or simply 'pinyin') Alpha bet had been developed, but plans to replace Chinese characters with it were deferred, and the idea is no longer actively pursued. This change in priorities may have been due in part to pinyin's design being specific to Mandarin, to the exclusion of other dialects.[60]

Pinyin uses the Latin Alpha bet withdiacriticsto represent the phonology of Standard Chinese. For the most part, pinyin uses phonetic values for letters that reflect their existing pronunciations in Romance languages and theInternational Phonetic Alphabet(IPA). However, pairs of letters such asbandpthat correspond to avoicingdistinction in languages such as French instead represent theaspirationdistinction that is more abundant in Mandarin.[44]Pinyin also uses several consonantal letters to represent markedly different sounds from their assignments in other languages. For example, pinyinqandxcorrespond to sounds similar to Englishchandsh,respectively. While pinyin has become the predominant transliteration system for Mandarin, others includebopomofo,Wade–Giles,Yale,EFEOandGwoyeu Romatzyh.[61]

Notes

[edit]- ^Especially when distinguished from otherlanguages of China

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abDeFrancis (1984),p. 84.

- ^abDeFrancis (1968).

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 73.

- ^abRamsey (1987),p. 143.

- ^Boltz, William G. (1986). "Early Chinese Writing".World Archaeology.17(3): 420–436.doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979980.ISSN0043-8243.JSTOR124705.

- ^Keightley, David N. (1996). "Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China".Representations(56): 68–95.doi:10.2307/2928708.ISSN0734-6018.JSTOR2928708.

- ^DeFrancis, John (1989)."Chinese".Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems.University of Hawaii Press.ISBN978-0-8248-1207-2– via pinyin.info.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 64–65;Demattè (2022).

- ^abNorman (1988),p. 63.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 65–70.

- ^abDeFrancis (1984),pp. 155–156.

- ^Wieger (1915).

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 9.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 67.

- ^abcdWieger (1915),pp. 10–11.

- ^Lu, Xun(2005) [1934]. "An Outsider's Chats about Written Language". InMair, Victor H.;Steinhardt, Nancy S.; Goldin, Paul R. (eds.).Hawaiʻi Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture– via pinyin.info.

- ^Wieger (1915),p. 30.

- ^Björkstén (1994),p. 52.

- ^Björkstén (1994),pp. 31–43.

- ^Björkstén (1994),pp. 46–49.

- ^Huang, Liang; et al. (2002).Statistical Part-of-Speech Tagging for Classical Chinese.Text, Speech, and Dialogue: Fifth International Conference. pp. 115–122.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 80.

- ^"Taiwan Law Orders One-Way Writing".BBC.4 May 2004.

Official Taiwanese documents can no longer be written from right to left or from top to bottom in a new law passed by the country's parliament

- ^Go, Ping-gam (1995).Understanding Chinese Characters(in English and Chinese) (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Simplex. pp. 1–31.ISBN978-0-9623113-4-5.

- ^Norman (1988),p. ix.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 64–65.

- ^Rincon, Paul (2003)."Earliest Writing Found in China".BBC.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 64–67.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 69–70.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 70.

- ^McNaughton & Ying (1999),p. 24.

- ^McNaughton & Ying (1999),p. 43.

- ^Ramsey (1987),p. 151.

- ^Bruggeman (2006).

- ^Ramsey (1987),p. 152.

- ^Ramsey (1987),p. 147.

- ^Thorp, Robert L. (1981). "The Date of Tomb 5 at Yinxu, Anyang: A Review Article".Artibus Asiae.43(3): 239–246.doi:10.2307/3249839.JSTOR3249839.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 84.

- ^DeFrancis (1984),pp. 177–188.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 75.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 83.

- ^DeFrancis (1984),p. 154.

- ^Ramsey (1987),pp. 24–25.

- ^abcRamsey (1987),p. 88.

- ^Ramsey (1987),p. 87.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 109.

- ^DeFrancis (1984),p. 150.

- ^Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). "Language Contact and Globalisation: The camouflaged influence of English on the world's languages with special attention to Israeli and Mandarin".Cambridge Review of International Affairs.16(2): 298–307.doi:10.1080/09557570302045.ISSN0955-7571.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 76.

- ^Ramsey (1987),p. 99.

- ^Lam, Wan Shun Eva (2004)."Second Language Socialization in a Bilingual Chat Room: Global and Local Considerations".Learning, Language, and Technology.8(3).

- ^"User's Manual of the Romanization of Minnanyu/Hokkien Spoken in Taiwan Region".Taiwan Ministry of Education. 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-08-15.Retrieved2009-08-24.

- ^Norman (1988),p. 72.

- ^abcDeFrancis (1984),p. 92.

- ^Wieger (1915),p. 19.

- ^Björkstén (1994),pp. 17–18.

- ^McNaughton & Ying (1999),p. 20.

- ^Wang, Gwo-En; Wang, Jhing-Fa (1994). "A New Hierarchical Approach for Recognition of Unconstrained Handwritten Numerals".IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics.40(3): 428–436.doi:10.1109/30.320824.S2CID40291502.

- ^Su, Hsi-Yao (2005).Language Styling and Switching in Speech and Online Contexts: Identity and Language Ideologies in Taiwan(Ph.D. thesis). Austin: University of Texas.

- ^Ramsey (1987),pp. 144–154.

- ^DeFrancis (1984),p. 265.

Works cited

[edit]- Björkstén, J. (1994).Learn to Write Chinese Characters.Yale University Press.ISBN0-300-05771-7.

- Bruggeman, Sebastien (2006).Chinese language processing and computing(PDF)(Thesis). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 May 2006.

- DeFrancis, John(1968).Advanced Chinese Reader.Murray.ISBN0-300-01083-4.

- ——— (1984).The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy.University of Hawaiʻi Press.ISBN0-824-80866-5.

- Hannas, William C. (1997).Asia's Orthographic Dilemma.University of Hawaiʻi Press.ISBN978-0-824-81892-0.

- McNaughton, William; Ying, Li (1999).Reading and Writing Chinese.Tuttle.ISBN0-804-83206-4.

- Norman, Jerry(1988).Chinese.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-29653-6.

- Demattè, Paola (2022).The origins of Chinese writing.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-197-63576-6.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987).The Languages of China.Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-01468-X.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007).ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese.University of Hawaiʻi Press.ISBN978-0-824-82975-9.

- Wieger, L. (1965) [1915].Chinese Characters.Dover.ISBN0-486-21321-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Chen, Ping (1999).Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-64572-0.

- Qiu, Xigui(2000) [1988].Chinese Writing.Translated by Mattos, Gilbert L.; Norman, Jerry. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California.ISBN978-1-557-29071-7.

- Snow, Don (2004).Cantonese as Written Language: The Growth of a Written Chinese Vernacular.Hong Kong University Press.ISBN978-9-622-09709-4.

External links

[edit]- Yue E Li and Christopher Upward. "Review of the process of reform in the simplification of Chinese Characters".Archived2007-01-02 at theWayback Machine(Journal of Simplified Spelling Society, 1992/2 pp. 14–16, later designated J13)