Yellow journalism

Injournalism,yellow journalismand theyellow pressare American newspapers that use eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations for increased sales. The English term is chiefly used in the US. In the United Kingdom, a similar term istabloid journalism.Other languages, e.g. Russian (Жёлтая прессаzhyoltaya pressa), sometimes have terms derived from the American term. Yellow journalism emerged in the intense battle for readers by two newspapers in New York City in 1890s. It was not common in other cities.

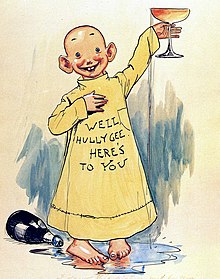

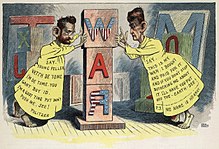

Joseph Pulitzerpurchased theNew York Worldin 1883 and told his editors to use sensationalism, crusades against corruption, and lavish use of illustrations to boost circulation.William Randolph Hearstthen purchased the rivalNew York Journalin 1895. They engaged in an intense circulation war, at a time when most men bought one copy every day from rival street vendors shouting their paper's headlines. The term "yellow journalism" originated from the innovative popular "Yellow Kid"comic strip that was published first in theWorldand later in theJournal.

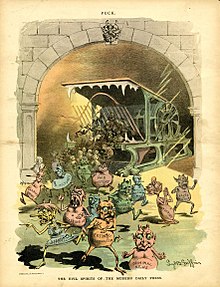

This type of reporting was characterized by exaggerated headlines, unverified claims, partisan agendas, and a focus on topics like crime, scandal, sports, and violence. Historians have debated whether Yellow journalism played a large role in inflaming public opinion about Spain's atrocities in Cuba at the time, and perhaps pushing the U.S. into the Spanish-American War of 1898. Most historians say it did not do so. The two papers reached a working class Democratic audience, and the nation's upscale Republican decision makers (such as President William McKinley and leaders in Congress) seldom read the Yellow press.[1]

Definitions

Journalism historian W. Joseph Campbell described yellow press newspapers as having daily multi-column front-page headlines covering a variety of topics, such as sports and scandal, using bold layouts (with large illustrations and perhaps color), heavy reliance on unnamed sources, and unabashed self-promotion. The term was extensively used to describe two major New York City newspapers around 1900 as they battled for circulation.[2]: 156–160 [3]

Journalism historianFrank Luther Mottused five characteristics to identify yellow journalism:[4]

- scare headlines in huge print, often sensationalizing minor news

- lavish use of pictures, or imaginary drawings

- use of faked interviews, misleading headlines,pseudoscience,and a parade of false learning from so-called experts

- emphasis on full-color Sunday supplements, usually with superficial articles andcomics

- dramatic sympathy with the "underdog" against the system.

Another common feature was emphasizing sensationalized crime reporting to boost sales and excite public opinion.[5]

Origins: Pulitzer vs. Hearst

Coinage and early usage

An English magazine in 1898 noted, "All American journalism is not 'yellow', though all strictly 'up-to-date' yellow journalism is American!"[6]

The term was coined in the mid-1890s to characterize the sensational journalism in the circulation war betweenJoseph Pulitzer'sNew York WorldandWilliam Randolph Hearst'sNew York Journal.The battle peaked from 1895 to about 1898, and historical usage often refers specifically to this period. Both papers were sensationalizing the news in order to drive up circulation, although the newspapers did serious reporting as well.Richard F. Outcault,the author of a popular cartoon strip, theYellow Kid,was tempted away from theWorldby Hearst and the cartoon accounted substantially towards a big increase in sales of theJournal.[7]

The term was coined by Erwin Wardman, the editor of theNew York Press.Wardman was the first to publish the term but there is evidence that expressions such as "yellow journalism" and "school of yellow kid journalism" were already used by newsmen of that time. Wardman never defined the term exactly. Possibly it was a mutation from earlier slander where Wardman twisted "new journalism" into "nude journalism".[2]: 32–33 Wardman had also used the expression "yellow kid journalism"[2]: 32–33 referring tothe then-popular comic stripwhich was published by both Pulitzer and Hearst during a circulation war.[8]

Hearst in San Francisco, Pulitzer in New York

Joseph Pulitzer purchased theNew York Worldin 1883 after making theSt. Louis Post-Dispatchthe dominant daily in that city. Pulitzer strove to make theNew York Worldan entertaining read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and contests that drew in new readers. Crime stories filled many of the pages, with headlines like "Was He a Suicide?" and "Screaming for Mercy".[9]In addition, Pulitzer charged readers only two cents per issue but gave readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information (the only other two-cent paper in the city never exceeded four pages).[10]

While there were many sensational stories in theNew York World,they were by no means the only pieces, or even the dominant ones. Pulitzer believed that newspapers were public institutions with a duty to improve society, and he put theWorldin the service of social reform. Pulitzer explained that:[11]

The American people want something terse, forcible, picturesque, striking, something that will arrest their attention, enlist their sympathy, arouse their indignation, stimulate their imagination, convince their reason, [and] awaken their conscience.

Just two years after Pulitzer took it over, theWorldbecame the highest-circulation newspaper in New York, aided in part by its strong ties to theDemocratic Party.[12]Older publishers, envious of Pulitzer's success, began criticizing theWorld,harping on its crime stories and stunts while ignoring its more serious reporting—trends which influenced the popular perception of yellow journalism.Charles Dana,editor of theNew York Sun,attackedThe Worldand said Pulitzer was "deficient in judgment and in staying power."[13]

Pulitzer's approach made an impression onWilliam Randolph Hearst,a mining heir who acquired theSan Francisco Examinerfrom his father in 1887. Hearst studied theWorldand resolved to make theSan Francisco Examineras bright as Pulitzer's paper.[14]

Under his leadership, theExaminerdevoted 24 percent of its space to crime, presenting the stories asmorality plays,and sprinkled adultery and "nudity" (by 19th-century standards) on the front page.[15]A month after Hearst took over the paper, theExaminerran this headline about a hotel fire:

HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Stricken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. TheExaminerSends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning's Train – A History of Hotel del Monte – The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry – Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.[16]

Hearst could be hyperbolic in his crime coverage; one of his early pieces, regarding a "band of murderers", attacked the police for forcingExaminerreporters to do their work for them. But while indulging in these stunts, theExamineralso increased its space for international news, and sent reporters out to uncover municipal corruption and inefficiency.

In one well remembered story,ExaminerreporterWinifred Blackwas admitted into a San Francisco hospital and discovered that poor women were treated with "gross cruelty". The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the piece appeared.[17]

Competition in New York

With the success of theExaminerestablished by the early 1890s, Hearst began looking for a New York newspaper to purchase, and acquired theNew York Journalin 1895, a penny paper.

Metropolitannewspapersstarted going after department store advertising in the 1890s, and discovered the larger the circulation base, the better. This drove Hearst; following Pulitzer's earlier strategy, he kept theJournal's price at one cent (compared toThe World's two-cent price) while providing as much information as rival newspapers.[10]The approach worked, and as theJournal's circulation jumped to 150,000, Pulitzer cut his price to a penny, hoping to drive his young competitor into bankruptcy.

In a counterattack, Hearst raided the staff of theWorldin 1896. While most sources say that Hearst simply offered more money, Pulitzer—who had grown increasingly abusive to his employees—had become an difficult man to work for, and manyWorldemployees were willing to jump for the sake of getting away from him.[18]

Although the competition between theWorldand theJournalwas fierce, the papers were temperamentally alike. Both were Democratic, both were sympathetic to labor and immigrants (a sharp contrast to upscale papers like theNew-York Tribune'sWhitelaw Reid,that blamed poverty on moral defects[13]). Both invested enormous resources in their Sunday editions, which functioned like weekly magazines, going beyond the normal scope of daily journalism.[19]

Their Sunday entertainment features included the first colorcomic strippages.Hogan's Alley,a comic strip revolving around a bald child in a yellow nightshirt (nicknamedThe Yellow Kid), became exceptionally popular when cartoonistRichard F. Outcaultbegan drawing it in theWorldin early 1896. When Hearst hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artistGeorge Luksto continue the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids.[20]The use of "yellow journalism" as a synonym for over-the-top sensationalism thus started with more serious newspapers commenting on the excesses of "the Yellow Kid papers".

Spanish–American War

Pulitzer and Hearst in the 1920s and 1930s were blamed as a cause of entry into theSpanish–American Wardue to sensationalist stories or exaggerations of the terrible conditions in Cuba.[21]: 608 However, the majority of Americans did not live in New York City, and the decision-makers who did live there relied more on staid newspapers liketheTimes,The Sun,orthePost.[citation needed]James Creelmanwrote an anecdote in his memoir that artistFrederic Remingtontelegrammed Hearst to tell him all was quiet in Cuba and "There will be no war." Creelman claimed Hearst responded "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." Hearst denied the veracity of the story, and no one has found any evidence of the telegrams existing.[22][2]: 72 Historian Emily Erickson states:

Serious historians have dismissed the telegram story as unlikely.... The hubris contained in this supposed telegram, however, does reflect the spirit of unabashed self-promotion that was a hallmark of the yellow press and of Hearst in particular.[21]

Hearst became awar hawkaftera rebellionbroke out in Cuba in 1895. Stories of Cuban virtue and Spanish brutality soon dominated his front page. While the accounts were of dubious accuracy, the newspaper readers of the 19th century did not expect, or necessarily want, his stories to be pure nonfiction. Historian Michael Robertson has said that "Newspaper reporters and readers of the 1890s were much less concerned with distinguishing among fact-based reporting, opinion and literature."[23]

Pulitzer, though lacking Hearst's resources, kept the story on his front page. The yellow press covered the revolution extensively and often inaccurately, but conditions on Cuba were horrific enough. The island was in a terrible economic depression, and Spanish generalValeriano Weyler,sent to crush the rebellion, herded Cuban peasants intoconcentration camps,leading hundreds of Cubans to their deaths. Having clamored for a fight for two years, Hearst took credit for the conflict when it came: A week after the United States declared war on Spain, he ran "How do you like theJournal'swar? "on his front page.[24]In fact, PresidentWilliam McKinleynever read theJournal,nor newspapers like theTribuneand theNew York Evening Post.Moreover, journalism historians have noted that yellow journalism was largely confined to New York City, and that newspapers in the rest of the country did not follow their lead. TheJournaland theWorldwere pitched to Democrats in New York City and were not among the top ten sources of news in regional papers; they seldom made headlines outside New York City. Piero Gleijeses looked at 41 major newspapers and finds:

- Eight of the papers in my sample advocated war or measures that would lead to war before the Maine blew up; twelve joined the pro-war ranks in the wake of the explosion; thirteen strongly opposed the war until hostilities began. The borders between the groups are fluid. For example, theWall Street JournalandDun's Reviewopposed the war, but their opposition was muted. TheNew York Herald,theNew York Commercial Advertiserand theChicago Times-Heraldcame out in favour of war in March, but with such extreme reluctance that it is misleading to include them in the pro-war ranks.[25]

War came because public opinion was sickened by the bloodshed, and because leaders like McKinley realized that Spain had lost control of Cuba.[26]These factors weighed more on the president's mind than the melodramas in theNew York Journal.[27]Nick Kapur says that McKinley's actions were based more on his values of arbitrationism, pacifism, humanitarianism, and manly self-restraint, than on external pressures.[28]

When the invasion began, Hearst sailed directly to Cuba as a war correspondent, providing sober and accurate accounts of the fighting.[29]Creelman later praised the work of the reporters for exposing the horrors of Spanish misrule, arguing, "no true history of the war... can be written without an acknowledgment that whatever of justice and freedom and progress was accomplished by the Spanish–American War was due to the enterprise and tenacity ofyellow journalists,many of whom lie in unremembered graves. "[30]

After the war

Hearst was a leading Democrat who promotedWilliam Jennings Bryanfor president in 1896 and 1900. He later ran for mayor and governor and even sought the presidential nomination, but lost much of his personal prestige when outrage exploded in 1901 after columnistAmbrose Bierceand editorArthur Brisbanepublished separate columns months apart that suggested theassassination of William McKinley.When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, critics accused Hearst's Yellow Journalism of drivingLeon Czolgoszto the deed. It was later presumed that Hearst did not know of Bierce's column, and he claimed to have pulled Brisbane's after it ran in a first edition, but the incident would haunt him for the rest of his life, and all but destroyed his presidential ambitions.[31]

When later asked about Hearst's reaction to the incident, Bierce reportedly said, "I have never mentioned the matter to him, and he never mentioned it to me."[32]

Pulitzer, haunted by his "yellow sins,"[33]returned theWorldto its crusading roots as the new century dawned. By the time of his death in 1911, theWorldwas a widely respected publication, and would remain a leading progressive paper until its demise in 1931. Its name lived on in theScripps-HowardNew York World-Telegram,and then later theNew York World-Telegram and Sunin 1950, and finally was last used by theNew York World-Journal-Tribunefrom September 1966 to May 1967. At that point, only one broadsheet newspaper was left in New York City.

See also

- Big lie– Propaganda technique

- Clickbait

- Fake news

- Godi media

- The Yellow Journal

Notes

- ^On the historiography see W. Joseph Campbell, "Not to Blame: The Yellow Press and the Spanish-American War" in hisYellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies(Praeger, 2003) pp. 97–150; and David R. Spencer. "The Spanish-American War and the Hearst Myth" in hisThe Yellow Journalism: The Press and America's Emergence as a World Power(Northwestern UP, 2007) pp.123–152.

- ^abcdCampbell, W. Joseph (2001).Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies.Greenwood Publishing Group.ISBN0-275-96686-0.OCLC55648237.

- ^W. Joseph Campbell, "Yellow journalism."The international encyclopedia of journalism studies(2019): 1-5.online

- ^Mott, Frank Luther (1941).American Journalism.Routledge/Thoemmes Press. p. 539.ISBN978-0415228947.

- ^Kaufman, Peter (2013).Skull in the Ashes.University of Iowa Press. p. 32.ISBN978-1609382131.OCLC830646791.

- ^Cited inOxford English Dictionary"Yellow" sense #3

- ^David M. Ball, "From Immigrants to Filibusters: The Curious Case of R.F. Outcault's Yellow Kid."Immigrants and Comics(Routledge, 2021) pp.72–88. [https:// taylorfrancis /chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315643991-4/immigrants-filibusters-david-ballsummary.

- ^Wood 2004

- ^Swanberg 1967,pp. 74–75

- ^abNasaw 2000,p. 100

- ^Quoted in Darrell M. West,The Rise and Fall of the Media Establishment(Bedford / St. Martin's, 2001), p.43.

- ^Swanberg 1967,p. 91

- ^abSwanberg 1967,p. 79

- ^Nasaw 2000,pp. 54–63

- ^Nasaw 2000,pp. 75–77

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 75

- ^Nasaw 2000,pp. 69–77

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 105

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 107

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 108

- ^abErickson, Emily (2011). "Spanish-American War and the Press". In Vaughn, Stephen (ed.).Encyclopedia of American Journalism.Routledge.ISBN978-1-78034-253-5.OCLC759036346.

- ^W. Joseph Campbell (December 2001)."You Furnish the Legend, I'll Furnish the Quote".American Journalism Review.23(10): 16. Archived fromthe originalon June 3, 2013.RetrievedJanuary 13,2013.

- ^Nasaw 2000,quoted on p. 79

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 132

- ^Gleijeses, Piero (November 2003). "1898: The Opposition to the Spanish-American War".Journal of Latin American Studies.35(4): 685.doi:10.1017/s0022216x03006953.S2CID145094314.

- ^Kane, Thomas M (2009).Theoretical Roots of US Foreign Policy: Machiavelli and American Unilateralism.Routledge. p. 64.ISBN978-0-415-54503-7.OCLC1031900158.

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 133

- ^Kapur, Nick (March 2011). "William McKinley's Values and the Origins of the Spanish-American War: A Reinterpretation".Presidential Studies Quarterly.41(1): 18–38.doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2010.03829.x.JSTOR23884754.

- ^Nasaw 2000,p. 138

- ^Smythe 2003,p. 191

- ^Nasaw 2000,pp. 156–58

- ^Bonnet, Theodore (March 1916). "William R. Hearst: A Critical Study".Lantern.1(12): 365–80.

- ^Emory & Emory 1984,p. 295

Sources

- Emory, Edwin; Emory, Michael (1984),The Press and America(4th ed.),Prentice Hall

- Nasaw, David (2000),The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst,Houghton Mifflin

- Smythe, Ted Curtis (2003).The Gilded Age Press, 1865–1900.pp. 173–202. Archived fromthe originalon July 16, 2012.RetrievedSeptember 18,2017.

- Swanberg, W.A (1967),Pulitzer,Charles Scribner's Sons

- Wood, Mary (February 2, 2004),"Selling the Kid: The Role of Yellow Journalism",The Yellow Kid on the Paper Stage: Acting out Class Tensions and Racial Divisions in the New Urban Environment,American Studies at theUniversity of Virginia

Further reading

- Apfeldorf, Michael. "Helping Students Reflect on the Era of Yellow Journalism through Historical Cartoons and Newspapers."Social Education88.1 (2024): 57-61.

- Burge, Daniel J. "A Delayed Revenge:" Yellow Journalism "and the Long Quest for Cuba, 1851–1898."Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era22.3 (2023): 243-259.abstract[relevant?–discuss]

- Miller, Bonnie M. "Did Fake News Unite the Home Front behind a War with Spain? A Reconsideration of US Press Coverage, 1895–1898."Home Front Studies1.1 (2021): 1-31.online[relevant?–discuss]

- Frisken, Amanda.Graphic news: How sensational images transformed nineteenth-century journalism(U of Illinois Press, 2020)online.[relevant?–discuss]

- Carey, Craig. "Breaking the News: Telegraphy and Yellow Journalism in the Spanish-American War."American Periodicals26#2 (2016), pp. 130–48.online[relevant?–discuss]

- Fellow, Anthony R.American Media History(2nd ed. Wadsworth, 2010) pp.145–174, university textbook;

- Kaplan, Richard L. "Yellow Journalism" in Wolfgang Donsbach, ed.The international encyclopedia of communication(2008)online

- Vaughn, Stephen. ed.Encyclopedia of American Journalism(Routledge, 2008)online

- Spencer, David Ralph.The yellow journalism: The press and America's emergence as a world power(Northwestern University Press, 2007)online.

- Campbell, W. Joseph.Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, De-fining the Legacies(Praeger, 2001)[excessive citations]

- Winchester, Mark D. (1995), "Hully Gee, It's a WAR! The Yellow Kid and the Coining of Yellow Journalism",Inks: Cartoon and Comic Art Studies,vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 22–37[relevant?–discuss]

- Milton, Joyce (1989),The Yellow Kids: Foreign correspondents in the heyday of yellow journalism,Harper & Row[relevant?–discuss]

- Welter, Mark M. (Winter 1970), "The 1895–1898 Cuban Crisis in Minnesota Newspapers: Testing the 'Yellow Journalism' Theory",Journalism Quarterly,vol. 47, pp. 719–24[relevant?–discuss]