Zahabiya

ZahabiyaSufism(Persian:سلسله ذهبیه,ZahabiyaSilsila) is aShiiteorder.The history ofdervishesfrom this order dates to the third centuryAHandMa'ruf al-Karkhi.Some believe that the order originated during the ninth century AH in Iran; it first became popular inKhorasanand then inShirazduring the earlySafavid period.[1]

| Part ofa seriesonIslam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

History[edit]

Zahabiya is aSufiorder[2]ofShia Islamwhich has its roots from the ninth century AH,[3]composed of followers of Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi Mashhadi.[4][5]InIran,after the formation of theSafavidstate, the order spread and other orders branched out from it. For this reason, it is known as"Umm al-Salasel"( "mother of the branches" ).[6]The order originated from the SufiKubrawiyaorder ofMir Sayyid Ali Hamadani.[5]Zahabiya is asilsila(chain of lineage) of thetariqa(school) of Kubrawiya. It was considered it to be aSunniorder beforeBorzeshabadibut becameShiiteafterwards, especially after theSafavids forced conversion of Iran to Shia Islam.[7]

Possible founders[edit]

There are several theories about Zahabiya's founder. Its founder has been believed to beNajm al-Din Kubra,[8]who died in 1221CE(618 AH). His nickname was "Abu al-Janab".[9][10]He was the twelfthQutb(saint) of the Zahabiya order. His titles are Sheikh Wali Tarash, Kubra and Tama Al-Kubra, and Zahabiya later became known as the Zahabiya Kubrawiya.[11]His title was "Tama Al-Kubra" (Doomsday). He won arguments with other scholars. "Tama" was later dropped, and he was called "Kubra".[12]The poetJamiwrote about his title of "Wali Tarash" (Wali-maker), "Because in the victories of ecstasy, his blessed sight on whoever fell, reached the position of final enlightenment".[13]He had many followers, some of whom were well-known Sufis such asMajd al-Din Baghdadi(died 1209 CE),[14]Saaduddin Hammuyeh (died 1251),[15]Baba Kamal Jundi,[16]and Razi al-Din Ali Lala Esfarayeni (died 1244).[17][18][19]Qazi Nurullah Shustari,in his bookMajalis al-muminincites the number of Najm al-Din Kubra's followers as twelve and writes: "Because his true elders were limited to thetwelve Imams,he inevitably observed the number of elders on the part of his disciples and, as it is mentioned the bookTarikh-i guzida,he did not accept more than twelve disciples during his lifetime, but each of them became of the greatest scholar of the time ".[20]Najm al-Din Kubra was the son-in-law ofRuzbihan Baqli,and had two sons.[21]

Another founder of Zahabiya order may have been Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani, who died in 1423 CE (826 AH).[22]He was bornc. 1339 CE(740 AH), and was a disciple and son-in-law ofMir Sayyid Ali Hamadani.Twelve disciples are mentioned for him, one of whom was Abdullah Borzeshabadi.[23]During the departure ofMuhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani,Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani was killed at the order ofShah Rukhas the main agitator against theTimurid Empire.[24]

Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi is also cited as the founder of the order. Seyyed Abdullah ibn Abdul Hai Ali Al-Hussein, nicknamed "Majzoob" ( "engrossed" ), was from the village ofBorzeshabadinMashhad County,Razavi Khorasan province.Bornc. 1368 to 1378 CE(770 to 780 AH), he was the son-in-law of his teacher Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani and was also taught byQasim-i Anvar(died 1433).[25][26]After the death of Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani, Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi taught for nearly thirty years and died in the early ninth century AH (after 1446 CE). Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi wrote a number oftreatises, including the "Kamaliyeh treatise" (aboutIrfanandShariaetiquette).[27]He also wrote lyric poetry.[28]

Alternative theory[edit]

According to some narratives, Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani[22](theQutbofKubrawiya) saw in a dream a young disciple,Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani,made him his successor (leaves the cloak ofMir Sayyid Ali Hamadanito Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani), and introduceds him as theMahdi(savior of the world). Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani entrusted his followers to Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani, but one (Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi)[4]refuses to obey him and leaves. Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani said, "Zahaba Abdullah"(" Abdullah is gone "). The road taken by Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi became known as Zahabiya, a branch of the Kubrawiya order.[29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36]

Qutb[edit]

Sufisbelieve that a seeker should follow the one who leads him, and a Sufi should choose a mentor. This guide is known aspir( "elder" ),wali( "guardian" ),sheikh( "lord, master" ) andQutb(a perfect human). A Qutb is a person who is in the sight of God and like the heart ofMuhammad.A Qutb is also calledAbdul Elah( "servant of God" ).[37]

Asadullah Khavari[38]introduced Qutb from the point of view of Zahabiya: "The meaning of the Qutb in Zahabiya view is perfect men and partial saints who have attained degrees and perfections through conduct and divine passion, and after the stage ofannihilation[of theEgo], revived by God and they have reached the degree of the understanding of the immediate guardian of God and the owner of time, who is the Qutb of all Qutbs of the time. "[39]

Qutb genealogy[edit]

In the appendices of the bookTohfeh Abbasi,[40]the names of the Qutbs of Zahabiya order are listed in the following order:[41][42][43][44]

| Zahabiya genealogy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Qutb of Nateq-Samet[edit]

In Zahabiya, the Qutb (the current leader) is calledQutb-e Nateq( "the rhetorical Qutb" ); his successor is calledQutb-e Samet( "the silent Qutb" ) during the life ofQutb-e Nateq.These terms are also used by the ShiiteIsma'ilismsect.[71]

Other names[edit]

Zahabiya is the best-known name of the order, but it is also known as Elahieh, Mohammadiyyah, Alawiyah, Razaviyyah, Mahdieh, Marufiyah, Kubrawiya, and Ahmadiyya. The latter name was bestowed by Mirza Ahmad Abdulhay Mortazavi Tabrizi (known as Vahid al-Owlia, the 37th Qutb of Zahabiya).[72][73]

Mohammad Ali Moazzen Khorasani (the 29th Qutb of Zahabiya) citesUmm al-Salasel( "mother of the branches" ) as a name for Zahabiya: "In Iran, after the formation of theSafavid dynastyand the promotion of theShiite religion,only the Zahabiya order, which was specific to the Shiites, expanded; and for this reason, it is also calledUmm al-Salaslbecause over the last few centuries, many branches have been formed of it. "[74]

The order is said to have been named Zahabiya ( "golden" ) because itsQutbspractice an alchemy of the soul; a seeker becomes spiritually refined, like gold. Until a seeker reaches this level of purity, they cannot guide anyone. There were noSunnisperson in the order; their elders and guardians were allTwelvers.[75][76]TheHadith of Golden Chainis also considered to authorize the order.[42]

Claims[edit]

A number of claims have been made about the authenticity of Zahabiya genealogy.[77][78][79][80] The order has been attributed toThe Fourteen Infallibles.Some followers believe that it originated withImam Reza(the eighth Shiite Imam) throughMa'ruf al-Karkhi.Imam Reza was a descendant ofMuhammad.[81][82]Ma'ruf al-Karkhiwas a mystic fromKarkhinBaghdad.Bornc. 750–760 CE,he reportedly died in 815 CE (200 AH).[83][84][85][86]It was said that fourteen sects, known as the Marufiyah sects, branched out from him.[87]Ma'ruf al-Karkhi's connection to, and meeting with, Imam Reza and his conversion to Islam are somewhat controversial. Some (including Ibn al-Husayn al-Sulami in his book,Tabaqat al-Sufiah) believe that he was converted by Imam Reza;[88][82]Ali Hujwiriwrote: "Ma'ruf al-Karkhi was converted to Islam by Imam Reza, and was very dear to him."[89]In the book,Wafyat al-A'yan,Ibn Khallikanmentioned Ma'ruf al-Karkhi's conversion to Islam by Imam Reza and considered him one of the Imam's patrons.[90]According to some sources, Ma'ruf al-Karkhi's Christian parents also converted to Islam after he did.[91]He was described elsewhere as Imam Reza's gatekeeper.[92]Ma'ruf al-Karkhi broke a bone in a crowd at the imam's house and later died.[88]In the book,Tazkirat al-Awliya,Attar of Nishapurwrote that he became ill after the fracture;[93]according to other sources, he was disabled for the rest of his life.[94]

Others question a connection between Ma'ruf al-Karkhi and Imam Reza. The story of Ma'ruf al-Karkhi's conversion to Islam and his responsibility as gatekeeper was first told by Ibn al-Husayn al-Sulami without documentation. Others who told this story after him narrated it in the form of a messenger.[95]Ma'ruf al-Karkhi was not mentioned in anyrijalidealing with the companions and patrons of the imams. According toAyatollah Borqei,"There is no name of" Ma'ruf al-Karkhi "in the books of Shiite rijals and his condition is unknown and not even a singlehadithfrom him - neither in theprinciples of religionnor in theancillaries- has been narrated by the Imams through him and some of the hadiths attributed to him are undocumented and has no evidence. "[96]Mohammad-Baqer Majlesiwrote, "Ma'ruf al-Karkhi" is not known to have served Imam Reza and to say that he was the gatekeeper of the Imam is of course wrong; Because all the servants and patrons of that Imam fromSunniand Shiite have been recorded in the books of our rijals and the fanatical Sunnis who used to travel and narrate the hadith of that Imam have mentioned their names, if this man was the patron of that Imam, of course they quoted. "[97]Crowds at Imam Reza's house large enough to trample a person are incompatible with the fact that the imam was guarded by theAbbasid caliphal-Ma'mun,and Shiites could not approach the imams.[98]According to Sufi scholars, the position ofQutbcannot be transferred to the next Qutb during the lifetime of the imam who is Qutb at the time.[99]Imam Reza died in 818 CE (203 AH),[100]and Ma'ruf al-Karkhi reportedly died in 815 CE (200 AH). Ma'ruf al-Karkhi was not Qutb during his lifetime, because two Qutbs could not simultaneously exist. However,Sari al-Saqatiwas a student of Ma'ruf al-Karkhi.[101]According to histories, the al-Ma'mun summoned Imam Reza toMervin 815 CE (200 AH).[83][102]The imam traveled to Merv throughBasra,AhvazandFarsbecause the cities ofQomandKufawere Shiite and believed inAhl al-Bayt;passing through them would support Imam Reza against al-Ma'mun's agents.[103]Morteza Motahhariwrote, "The route that al-Ma'mun chose for Imam Reza was a specific path that did not pass through the Shiite-settled locations because they were afraid of them. Al-Ma'mun ordered not to bring the Imam throughKufa,to bring him toNishapurthrough Basra,Khuzestanand Fars ".[104]There was no mention of a trip toBaghdadfor Imam Reza before 815; he livedMedinauntil that year, and Ma'ruf al-Karkhi never left Baghdad.[105][106]Therefore, Ma'ruf al-Karkhi could not have been converted to Islam by Imam Reza.[77]

Because followers of Zahabiya attribute their authenticity to Imam Reza through Ma'ruf al-Karkhi, they believe that the imam narrated theHadith of Golden Chain[107]inNishapurand the order became known as Zahabiya ( "golden" ).[108]Ma'ruf al-Karkhi's relationship with Imam Reza is questionable. The Hadith of Golden Chain is a proof of the guardianship which the imam received from his father and entrusted to his son,Imam Jawad,not something he gave to Ma'ruf al-Karkhi.[109]There is no logical connection between this hadith and the name Zahabiya.[78]

Another claim is that no Sunnis were in the Zahabiya order; its elders and guardians wereTwelvers,and their authenticity reachesthe Infallible Imam.For this reason, they became known as Zahabiya; like gold, they are free of the disagreement and enmity of the family of Muhammad.[110]However, most Zahabiya Qutbs were Sunni; some, such asJunayd Baghdadi,Ahmad Ghazali,Abul Qasim Gurgani,Abubakr Nassaj Toosi andAbu al-Najib Suhrawardi,were not Twelvers.[111]

Through their Qutbs, Zahabiya seekers' existential copper turns into gold; they became free of materialism and egotistical temptation, and may guide other seekers.[110]However, some Zahabiya Qutbs or followers have moral, political or social problems;[112]some Qutbs have drifted towardsFreemasonry.[113]When Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi[4]rebelled and disobeyed the order of his master Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani[22]to pledge allegiance toMuhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani,Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani said: "Zahaba Abdullah"(" Abdullah is gone "or" Abdullah became gold "). For this reason, the order was formed and named Zahabiya.[114]It is sometimes known as Zahabiya Eqteshashiah ( "Anarchy Zahabiya" ) because Sufis called sectarian unrest without the permission of a sect's current leaderEqteshash( "Anarchy" ); if it led to the formation of other independent sects, they were identified as baseless and unreliable with the addition ofEqteshashiah.[115]

Path of growth[edit]

Asadullah Khavari[38]has divided the history of eleven and a half centuries of the Zahabiya order (from the death of Ma'ruf al-Karkhi, the first Zahabiya Qutb, in 815 CE to the death of Jalaleddin Mohammad Majdolashraf Shirazi,[64]the 36th Zahabiya Qutb in 1913) into five periods:[116][79][42]

- The period of asceticism and worship: This period began with the death of Ma'ruf al-Karkhi and ended at the end of the fifth century AH and the death of Abubakr Nassaj Toosi[46](the eighth Zahabiya Qutb) in 1094 CE (487 AH). During this period, the Zahabiya Qutbs have no written works other than scattered sentences and short words.

- The period of the rise of Sufism, or the period of scholarship and authorship: This period began at the beginning of the sixth century AH withAhmad Ghazali(the ninth Zahabiya Qutb, who died in 1131 CE) and ended at the end of the ninth century AH and the death of Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani[22](the 20th Zahabiya Qutb, who died in 1424 or 1425 CE). Less than a century had passed when theMongol invasionbegan, and the defeat ofMuhammad II of Khwarazmby theHulagu Khanended theKhwarazmian Empirein 1231 CE (628 AH). Elders, seekers and disciples produced literature in thePersian language.

- The period of Sufi stagnation: This period lasted from the second half of the ninth century AH and the time of Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi[4](the 21st Zahabiya Qutb, who died in 1485–1488 CE) to the end of the twelfth century AH and the death ofSeyyed Qutb al-Din Mohammad Neyrizi(the 32nd Zahabiya Qutb) in 1760 CE (1173 AH). From the beginning of the ninth century, the basic principle of Sufism (monotheism) weakened and was replaced by theTawassulwith theAlidsand their descendants. Higher monastic teachings evolved intodervishes.At this time, Qutbs and elders such asSeyyed Qutb al-Din Mohammad Neyrizi,Mohammad Ali Moazzen Khorasani (the 29th Zahabiya Qutb) and Najibuddin Reza Tabrizi[60](the 30th Qutb) emerged.

- TheWalayahperiod: This period began at the end of the twelfth century AH and the beginning of the guidance of Agha Mohammad Hashem Darvish Shirazi[62](the 33rd Qutb) in 1760 CE, and ended in the early fourteenth century AH and the death of Jalaleddin Mohammad Majdolashraf Shirazi[64](the 36th Qutb) in 1913 (1331 AH). Sufism and its monastic teachings evolved from monotheism into theWalayahand guardianship ofthe imams,and Shia Islam turned from outward customs inward to the guardianship. From this period, many works by Agha Mohammad Hashem Darvish Shirazi, Jalaleddin Mohammad Majdolashraf Shirazi and Mirza Abulghasem Raz Shirazi (the 35th Qutb)[63]survive.

- Sufi modern period: From the beginning of the fourteenth century AH to the early 1990s, modern works have influenced Sufism.

Walayah[edit]

Zahabiya has divided theWalayah(religious guardianship) into two parts:[117]

- The Walayah of the whole:Shamsiya( "Sun" )

- The Walayah of the part:Qamariya( "Moon" )

According to Zahabiya,Shamsiyabelongs to Muhammad andhis twelve descendants.Qamariyaalso belongs to Sufi elders and Qutbs. Since all beings in the universe have to reach perfection and humanity through a perfect human being, andMahdiis inoccultation,a person who hasQamariyafrom Mahdi is always present like the Moon which reflects the light of the Sun, purifies the mirror of the heart and illuminates the world. For this reason, he is the instructor of the lunar world and obtains light from the Sun.[118][119]Zahabiya believes that the authenticity of itsQamariyareaches Imam Reza through Ma'ruf al-Karkhi, and the authenticity of itsShamsiyaleads to Muhammad through Imam Reza and his ancestors.[81]

Exaggeration and esotericism[edit]

Some believe that Zahabiya believe inexaggeration(ascribing divine characteristics to figures of Islamic history)[120]and esotericism; the inside of theQurancan be easily understood from its appearance.[121]Zahabiya interprets appearance without analogy;[122]the heart of the mystic is the spiritual house of God, and theMasjid al-Haramis the physical house.[123]

Monastic ceremonies[edit]

Zahabiya, like otherSufi orders,is associated with monastic ceremonies inkhanqahs.[121]One ceremony is the transfer of the cloak from the current Qutb to the next one. Another isSama( "listening while dancing" ).[124]Another tradition is the culture of mastership and discipleship.[125]

Place of origin[edit]

Zahabiya originated inGreater Khorasanand theKhuttalregion, the center of the Qutbs and Kubrawiya elders (especiallyMir Sayyid Ali Hamadaniand Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani).[22]This region was the center of Zahabiya's Qutbs from the ninth to eleventh centuries AH. The center of Zahabiya order then moved toShiraz;[126]during the time of Najibuddin Reza Tabrizi (the 30th Qutb),[60]its center moved toIsfahan.[127]Due to the pressure ofIslamic juristsduring the reign ofSultan Husayn,its center moved back to Shiraz.[128]The order also has followers outsideIran,[129][42]whose activities continue.[130]

Criticism[edit]

Zahabiya was formed with the rebellion and disobedience of Seyyed Abdullah Borzeshabadi[4]at the orders of his master, Khajeh Eshaq Khuttalani,[22]based on allegiance toMuhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani.It was Shia Islam's first coup.[77]Zahabiya's followers connect their line of Qutbs to Imam Reza through Ma'ruf al-Karkhi and attribute themselves to the Fourteen Infallibles, but there may not have been a connection between the imam and Ma'ruf al-Karkhi.[78][42]Although they say that all members of this genealogy wereShiites,some have beenSunni.[79][42]The discussion ofQamariyaand its succession is problematic.[131]Their division ofWalayahintoShamsiyaandQamariyaconsiders their Qutbs the Walayah ofQamariyawithout evidence from theQuranandhadiths.[79]Some Qutbs are ethically suspect.[78]

Zahabiya considers their Qutbs and elders as superhuman,[132]and claims to be pure.[132]The hadiths they cite to indicate their authenticity are weak and often invalid.[133]The genealogy of their Qutbs contains gaps, although the existence of a Qutb is obligatory at all times.[134][135][136][131][42]Zahabiya is related to anarchy, (Eqteshashiah) and its history is vague and unreliable.[42]According to Islamic narratives,Sufismwas not approved by Imam Reza.[137][73]Zahabiya's claims contain superstitions,[73]and some believe that they have corrupted Islam.[138][139]

Gallery[edit]

-

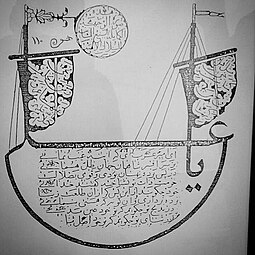

Tomb of Mohammad Karandehi,[57]known as Pire Palandouz (27th Qutb of Zahabiya)

-

Rescue Ship,a mystical painting by Jalaleddin Mohammad Majdolashraf Shirazi[64](36th Qutb)

-

Jalaleddin Mohammad Majdolashraf Shirazi[64]

-

Mirza Ahmad Khoshnevis, 37th Qutb

-

Mirza Ahmad Abdulhay Mortazavi Tabrizi,[65]known as Khoshnevis and Vahid al-Owlia (37th Qutb)

-

Abulfotuh Haaj Mirza Mohammad Ali Hobb Heydar,[67]38th Qutb

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "ذهبیه - دانشنامه جهان اسلام"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

سجادی, سید جعفر.فرهنگ معارف اسلامی(in Persian). Vol. ۲. تهران: انتشارات دانشگاه تهران. p. ۸۹۲.

چاپ: سوم، ۱۳۷۳ ش.

- ^

مادلونگ, ویلفرد.فرقههای اسلامی(in Persian). تهران: انتشارات اساطیر. p. ۹۱.

ترجمه ابوالقاسم سری، چاپ دوم، ۱۳۸۱ش.

- ^abcdef "بُرزِش آبادی ، سیّد شهاب الدین عبدالله بن عبدالحیّ مشهدی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab

مشکور, محمدجواد.فرهنگ فرق اسلامی(in Persian). مشهد: آستان قدس رضوی. p. ۱۹۸.

چاپ: دوم، ۱۳۷۲ش.

- ^

حسینی ذهبی (میرزا بابا شیرازی), سید ابوالقاسم بن عبدالنبی.مناهج أنوار المعرفة فی شرح مصباح الشریعة و مفتاح الحقیقة(in Persian). Vol. ۲. تهران: خانقاه احمدی. p. ۸۴۱.

محقق: باقری، محمدجعفر، ۱۳۶۳ش.

- ^

دزفولی, حسین. "تحلیلی از تصوف با تأکید بر فرق ذهبیه".فصلنامه کتاب نقد(in Persian): ۱۲۱.

شماره ۳۹، ۱۳۸۵ش.

- ^

شيرازى, محمدمعصوم.طرائق الحقائق(in Persian). Vol. ۲. كتابخانه سنائى. p. ۳۳۴.

تصحيح محمدجعفر محجوب

- ^

جامى, عبدالرحمن بن احمد.نفحات الانس من حضرات القدس(in Persian). سعدى. p. ۴۱۹ و ۴۲۴.

تحقيق مهدى توحيدى پور، چ دوم، ۱۳۶۶

- ^

يافعى يمنى مكى, اسعدبن على بن سليمان.مرآه الجنان و عبره اليقظان فى معرفه ما يعتبر من حوادث الزمان(in Arabic). Vol. ۴. بيروت: مؤسسة الاعلمى. p. ۴۰.

ط. الثانيه، 1390ق

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۲۱۱.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

شوشترى, قاضى سيدنوراللّه.مجالس المؤمنين(in Persian). Vol. ۲. اسلاميه. p. ۷۴.

۱۳۷۶ق

- ^

جامى, عبدالرحمن بن احمد.نفحات الانس من حضرات القدس(in Persian). سعدى. p. ۴۱۹.

تحقيق مهدى توحيدى پور، چ دوم، ۱۳۶۶

- ^ab "زندگینامه شیخ مجدالدین بغدادی(۶۰۶-۵۶۶ ه ق) – علماوعرفا"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "سعدالدین حمویه، محمد بن مؤید - ویکینور، دانشنامۀ تخصصی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "باباكمالجندی - مرکز دائرة المعارف بزرگ اسلامی - کتابخانه فقاهت"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "رضيالدين، علي بن سعيد جويني اسفرايني مشهور به رضيالدين علي لالا اسفرايني"(in Persian). 23 November 2014.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

جامى, عبدالرحمن بن احمد.نفحات الانس من حضرات القدس(in Persian). سعدى. p. ۴۲۴.

تحقيق مهدى توحيدى پور، چ دوم، ۱۳۶۶

- ^ فدایی مهربانی, مهدی(2009).پیدایی اندیشهٔ سیاسیِ عرفانی در ایران: از عزیز نسفی تا صدرالدین شیرازی(in Persian). نشر نی. p. ۷۲.ISBN9789641851073.

- ^

شوشترى, قاضى سيدنوراللّه.مجالس المؤمنين(in Persian). Vol. ۲. اسلاميه. p. ۷۳-۷۴.

۱۳۷۶ق

- ^ استخرى, احسان اللّه على.اصول تصوف(in Persian). معرفت. p. ۲۰۰.

- ^abcdefg "ختلانی خواجه اسحاق"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ استخرى, احسان اللّه على.اصول تصوف(in Persian). معرفت. p. ۳۲۳ و ۳۲۵.

- ^

حقيقت, عبدالرفيع.مكتب هاى عرفانى در دوران اسلامى(in Persian). كومش. p. ۳۰۸-۳۰۹.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۲۵۳-۲۵۴.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^ استخرى, احسان اللّه على.اصول تصوف(in Persian). معرفت. p. ۳۲۷-۳۲۸.

- ^ "رساله کمالیه (شهاب الدین امیر عبدالله برزش ابادی) - كتابخانه تخصصی تاریخ اسلام و ایران"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ استخرى, احسان اللّه على.اصول تصوف(in Persian). معرفت. p. ۳۳۰-۳۳۱.

- ^مدرسی چهاردهی، نور الدين، سيري در تصوف، تهران، اشراقي، دوم، ۱۳۶۱ش، ص ۲۷۳.

- ^ "افول کبرویه در آسیای مرکزی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ دویس, دوین."افول کبرویه در آسیای مرکزی - مگیران".فصلنامه تاریخ اسلام(in Persian).8(32): 147.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

شوشترى, قاضى سيدنوراللّه.مجالس المؤمنين(in Persian). Vol. ۲. p. ۱۴۴-۱۴۹.

(تهران، م ۸۲ـ۱۲۹۹/۱۸۸۱ق)

- ^

شيرازى, محمدمعصوم.طرائق الحقائق(in Persian). Vol. ۲. p. ۳۳۸-۳۴۰.

(تهـران، م۶۶ــ۴۵/۱۹۶۰ــ۱۳۹۹ش)

- ^

دویس, دوین; پورفرد, مژگان (22 December 2007)."افول کبرویه در آسیای مرکزی، دوین دویس".مجله تاریخ اسلام(in Persian).8(شماره 4 – زمستان 86 – مسلسل 32): ۱۴۷–۱۸۳.

دوره ۸، شماره ۴ - مسلسل ۳۲ - زمستان ۱۳۸۶، صفحه ۱۵۸

- ^ "زندگینامه سیّد شهاب الدین عبدالله بُرزِش آبادی«ختلانی »«مجذوب »«اسحاقی »(قرن هشتم)"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "خاندان برزش آبادی - دارالسیاده"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

تهانوى, محمدعلى (1966).موسوعه كشّاف اصطلاحات الفنون والعلوم(in Arabic). Vol. ۲. لبنان: مكتبة لبنان ناشرون. p. ۱۳۲۷.

تحقيق د. على دحروج، ۱۹۶۶

- ^ab "اسدالله خاوری - علم نت"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۱۶۳.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^ "کتاب تحفه عباسی: محمد علی موذن سبزواری"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

مؤذن خراسانى, محمدعلى.تحفه عباسى(in Persian). انس تك. p. ۵۵۴.

سال ۱۳۸۱

- ^abcdefgh "صوفیه ذهبیه و نعمت الهیه - پرسمان"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "سلسله ذهبيه - رازدار"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "ذهبیه – رازدار"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "اَبوعَلیِ کاتِب، ابوعلی حسن بن احمد کاتب مصری - مرکز دائرةالمعارف بزرگ اسلامی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "ابوبکر نساج طوسی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "بِدلیسی، ابو یاسر عمار بن یاسر بن مطربن سحاب - مرکز دائرةالمعارف بزرگ اسلامی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "رضی الدین علی لالا و شاگرد وی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "مقاله نشریه «شرح احوال و تحلیل اندیشه های عبدالرحمن اسفراینی» - علم نت"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "بنای تاریخی آرامگاه درویش محمود در روستای مومن آباد"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "آرامگاه شیخ رشیدالدّین محمّد بیدوازى ـ اسفراین مزارات ایران و جهان اسلام"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "شیخ شاه علی بیدوازی اسفراینی (908-830 ه.ق) – سپهر اسفراین"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "محمد خبوشانی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "غلامعلی نیشابوری - کتابخانه مجازی الفبا"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "سلسله كبرويه ذهبيه پس از حاجي محمد خبوشاني: تاجالدين حسين تبادكاني"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ اشرف امامی, علی; شرفایی مرغکی, محسن (12 March 2015)."سلسله کبرویه ذهبیه پس از حاجی محمد".پژوهشنامه عرفان(in Persian).1.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "شيخ محمد مقتدي کارندهي: معرفی آرامگاه پیر پالاندوز در مشهد"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ تکتم, بهرامی; علیرضا, فولادی (9 December 1393)."شیخ حاتم زراوندی".فصلنامه پژوهش زبان و ادبیات فارسی(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "موذن خراسانی، شاعر اهل بیت و عارف بزرگ سلسله ذهبیه با معرفی نسخه ای تازه یافته از دیوان او و تحلیل اشعار وی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abc "تبریزی نجیب الدین رضا"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "علی نقی اصطهباناتی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "آقا محمدهاشم درویش شیرازی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abc "رازِ شیرازی، میرزا ابوالقاسم حسین شریفی ذهبی شیرازی و پدرش میرزا عبدالنبی شریفی شیرازی (سیوچهارمین قطب سلسلۀ ذهبیه)"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abcde "جلال الدین محمد مجد الاشراف شیرازی"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "معرفى فرقه ذهبيه و نقد و بررسى برخى باورهاى آن"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "میرزا احمد اردبیلی معروف به" وحید الاولیاء ""(in Persian). 12 February 2016.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "۷. ابوالفتوح حاج ميرزا محمدعلي حبّ حيدر"(PDF)(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab "دکتر عبدالحمید گنجویان و دکتر حسین عصاره (عصاریان)"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

مدرسى چهاردهى, نورالدين.سيرى در تصوف(in Persian). اشراقى. p. ۲۸۲.

چ دوم، سال ۱۳۶۱

- ^

گروه نويسندگان.جستارى در نقد تصوف(in Persian). قم: تاظهور. p. ۸۷.

سال ۱۳۹۰

- ^

مدرسى چهاردهى, نورالدين.سيرى در تصوف(in Persian). اشراقى. p. ۲۹۰.

چ دوم، سال ۱۳۶۱

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۹۰-۹۱.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^abc "بررسی فرقه ذهبیه پایگاه جامع فرق، ادیان و مذاهب"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

مؤذن خراسانى, محمدعلى.تحفه عباسى(in Persian). انس تك. p. ۵۵۳.

سال ۱۳۸۱

- ^خاوری، اسداللهذهبیه (تصوف علمی، آثار ادبی)تهران: دانشگاه تهران، ۲۰۰۴، چاپ دوم

- ^ "فرقه ذهبیه دزفول - خوزستان خبر"(in Persian). 21 February 2018.Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abc "معرفى فرقه ذهبيه و نقد و بررسى برخى باورهاى آن - تبیان"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abcd "معرفی فرقه ذهبیه و نقد و بررسی برخی باورهای آن – مکتب تفکیک"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^abcd "مقاله نشریه معرفی فرقه ذهبیه و نقد و بررسی برخی باورهای آن - جویشگر علمی فارسی (علم نت)"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

حاجتى شوركى, سيدمحمد; صانعى, مرتضى."معرفى فرقه ذهبيه و نقد و بررسى برخى باورهاى آن".معرفت:۴۷–۶۱.

سال بيست و دوم ـ شماره 193 ـ دى 1392

- ^abخاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۹۴.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^ab "معروف کرخی کيست و چرا فرقههای شيعی مذهب صوفيه او را سرسلسله خود میدانند؟"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ab ابن اثير, عزالدين.الكامل فى التاريخ(in Arabic). Vol. ۵. دارالكتب العلميه. p. ۴۲۷.

- ^

ابن خلكان, محمدبن ابى بكر.وفيات الاعيان و انبا ابناالزمان(in Persian). Vol. ۵. قم: شريف رضى. p. ۲۳۳.

تحقيق احسان عباس، ۱۳۶۴

- ^

خطيب بغدادى, احمدبن على بن ثابت.تاريخ مدينه الاسلام و اخبار محدثيها و ذكر قطانها العلماء و من غير اهلها و وارديها(in Arabic). Vol. ۱۵. دارالغرب الاسلامى. p. ۲۷۵.

تعليق و تحقيق بشار عواد معروف، ۱۴۲۲ق

- ^

ابن جوزى, جمال الدين ابى الفرج.صفه الصفوه(in Arabic). بيروت: دارالمعرفه. p. ۵۹۶.

چ پنجم، ۱۴۲۶ق

- ^

سلطانى گنابادى, ميرزامحمدباقر.رهبران طريقت و حقيقت(in Persian). تهران: حقيقت. p. ۱۳۰.

چ پنجم، ۱۳۸۳

- ^ab

سلمى, ابى عبدالرحمن.طبقات الصوفيه(in Arabic). Vol. ۸۵. سوريه: دارالكتاب نفيس.

تحقيق نورالدين شريبه، چ دوم، ۱۴۰۶ق

- ^

هجويرى, على بن عثمان بن.كشف المحجوب(in Persian). تهران: اميركبير. p. ۱۴۱.

سال ۱۳۳۶

- ^

ابن خلكان, محمدبن ابى بكر.وفيات الاعيان و انبا ابناالزمان(in Persian). Vol. ۵. قم: شريف رضى. p. ۲۳۱.

تحقيق احسان عباس، ۱۳۶۴

- ^

عطار نيشابورى, فريدالدين.تذكرة الاولياء(in Persian). تهران: زوار. p. ۳۲۴-۳۲۵.

تصحيح متن و توضيح محمد استعلامى، چ هفتم، ۱۳۷۲

- ^

سلطانى گنابادى, ميرزامحمدباقر.رهبران طريقت و حقيقت(in Persian). تهران: حقيقت. p. ۱۱۱.

چ پنجم، ۱۳۸۳

- ^

عطار نيشابورى, فريدالدين.تذكرة الاولياء(in Persian). تهران: زوار. p. ۳۲۸.

تصحيح متن و توضيح محمد استعلامى، چ هفتم، ۱۳۷۲

- ^

قرشى, باقر شریف.موسوعه سيره اهل البيت(in Persian). Vol. ۳۱. قم: دارالمعروف. p. ۲۳۰.

تحقيق مهدى باقر القرشى، ۱۴۳۰ق

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۳۳۶.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^ برقعى, سيدابوالفضل.حقيقه العرفان يا تفتيش در شناسايى عارف و صوفى و حكيم و شاعر و درويش(in Persian). p. ۸۲ و ۸۵.

- ^

مجلسى, محمدباقر.عين الحياة(in Persian). اصفهان: نقش نگين. p. ۳۰۹.

تحقيق محمدكاظم عابدينى مطلق، چ دوم، ۱۳۸۹

- ^ برقعى, سيدابوالفضل.حقيقه العرفان يا تفتيش در شناسايى عارف و صوفى و حكيم و شاعر و درويش(in Persian). p. ۸۴-۸۵.

- ^

کاشانی, عزالدین محمود.مصباح الهدايه و مفتاح الكفايه(in Persian). قم: چاپخانه ستاره. p. ۳۰.

تصحيح جلال الدين همايى، چ چهارم، ۱۳۷۲

- ^ زركلى, خيرالدين.الاعلام قاموس تراجم لاشهر الرجال و االنساء من العرب و المستعربين و المستشرقين(in Arabic). Vol. ۵. بيروت: دارالعلم الملاميين. p. ۲۶.

- ^ برقعى, سيدابوالفضل.حقيقه العرفان يا تفتيش در شناسايى عارف و صوفى و حكيم و شاعر و درويش(in Persian). p. ۸۵-۸۶.

- ^

طبرى, محمدبن جرير.تاريخ الامم و الملوك(in Arabic). Vol. ۵. قاهره: چاپخانه استقامه. p. ۱۳۲.

۱۳۸۵ق

- ^

قرشى, باقر شریف.موسوعه سيره اهل البيت(in Persian). Vol. ۳۱. قم: دارالمعروف. p. ۳۷۸-۳۷۹.

تحقيق مهدى باقر القرشى، ۱۴۳۰ق

- ^

مطهرى, مرتضى.مجموعه آثار(in Persian). Vol. ۱۸. تهران: صدرا. p. ۱۲۴.

چ دوم، ۱۳۷۹

- ^

معروف الحسنى, هاشم.تصوف و تشيع(in Persian). مشهد: بنياد پژوهش هاى آستان قدس رضوى. p. ۴۸۹.

ترجمه سيدمحمدصادق عارف، ۱۳۶۹

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۲۶۸-۲۶۹.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^ صدوق, محمدبن على.عيون اخبارالرضا(in Arabic). Vol. ۲. نجف: منشورات المكتبة الحيدريه. p. ۱۳۳.

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۱۰۰.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

حاجى خلف, محمد; عابدى, احمد (January 1390)."تأملى در وجه تسميه، بررسى و نقد فرقه ذهبيه".پژوهش هاى اعتقادى ـ كلامى.1(2): ۳۲–۴۹.

شماره ۲، سال ۱۳۹۰

- ^ab

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۹۸.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۴۰۹.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^

خسروپناه, عبدالحسين."تحليلى از تصوف با تأكيد بر فرقه ذهبيه".كتاب نقد(in Persian) (۳۹): ۱۱۸–۱۳۶.

شماره ۳۹

- ^

وعيدى, سيدعباس.نگاهى منصفانه به ذهبيه(in Persian). راه نيكان. p. ۹۴.

سال ۱۳۸۸

- ^

گروه نويسندگان.جستارى در نقد تصوف(in Persian). قم: تاظهور. p. ۹۲ و ۹۶.

سال ۱۳۹۰

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۴۱۵.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۴۰۷-۴۱۰.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^ "معرفی فرقه ذهبیه و نقد و بررسی برخی باورهای آن"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۱۵۷.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۱۶۰-۱۶۱.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

رفیعی زابلی, حمیدالله. "فرقه ذهبیه".مجله کلام اسلامی(in Persian) (۷۵): ۶۵.

شماره۷۵، پاییز۱۳۸۹ش.

- ^abرفیعی زابلی, حمیدالله. "فرقه ذهبیه".مجله کلام اسلامی(in Persian) (۷۵): ۶۷.

شماره۷۵، پاییز۱۳۸۹ش.

- ^

دزفولی, حسین. "جستاری در تصوف".مجله رواق اندیشه(in Persian) (۴۷): ۱۰۰.

شماره ۴۷، آبان ۱۳۸۴ش.

- ^

حسینی ذهبی (میرزا بابا شیرازی), سید ابوالقاسم بن عبدالنبی.مناهج أنوار المعرفة فی شرح مصباح الشریعة و مفتاح الحقیقة(in Persian). Vol. ۱. تهران: خانقاه احمدی. p. ۴۶۶.

محقق: باقری، محمدجعفر، ۱۳۶۳ش.

- ^

رفیعی زابلی, حمیدالله. "فرقه ذهبیه".مجله کلام اسلامی(in Persian) (۷۵): ۶۸.

شماره۷۵، پاییز۱۳۸۹ش.

- ^

رفیعی زابلی, حمیدالله. "فرقه ذهبیه".مجله کلام اسلامی(in Persian) (۷۵): ۶۹.

شماره۷۵، پاییز۱۳۸۹ش.

- ^

رفیعی زابلی, حمیدالله. "فرقه ذهبیه".مجله کلام اسلامی(in Persian) (۷۵): ۶۱.

شماره۷۵، پاییز۱۳۸۹ش.

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۲۸۷.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^

خاورى, اسدالله.ذهبيه، تصوف علمى، آثار ادبى(in Persian). تهران: دانشگاه تهران. p. ۲۹۶.

سال ۱۳۸۳

- ^ "منابع و تاریخچه فرقه ذهبیه - پرسمان"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^

مادلونگ, ویلفرد.فرقههای اسلامی(in Persian). تهران: انتشارات اساطیر. p. ۹۱.

ترجمه ابوالقاسم سری، چاپ دوم، ۱۳۸۱ش.

- ^ab

خسروپناه, عبدالحسين."تحليلى از تصوف با تأكيد بر فرقه ذهبيه".كتاب نقد(in Persian) (۳۹): ۲۷.

شماره ۳۹

- ^ab

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۱۶۵-۱۶۷.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^

احسائى, ابن ابى جمهور.عوالى اللئالى العزيزيه فى الاحاديث المدينيه(in Arabic). Vol. ۴. قم: مطبعه سيدالشهداء. p. ۱۳۰-۱۳۱.

پاورقى عراقى، ۱۴۰۵ق

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۴۱۱.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^

شيرازى, محمدمعصوم.طرائق الحقائق(in Persian). Vol. ۱. كتابخانه سنائى. p. ۴۸۵.

تصحيح محمدجعفر محجوب

- ^

واحدى, سيدتقى.از كوى صوفيان تا حضور عارفان(in Persian). p. ۴۱۴-۴۱۵.

تصحيح محمدمهدى خليفه، چ دوم، ۱۳۷۵

- ^سفينة البحار ج۲ ص۵۸ چاپ فراهانی تهران و ج۵ ص۲۰۰ چاپ اسوه قم

- ^ "رویکرد ذهبیه به قرآن و حدیث - کتابخانه مجازی الفبا"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.

- ^ "فرقه ذهبيه يکي از فرقه هاي تصوف است"(in Persian).Retrieved30 October2021.